Features

Remembering Sumithra

By Uditha Devapriya

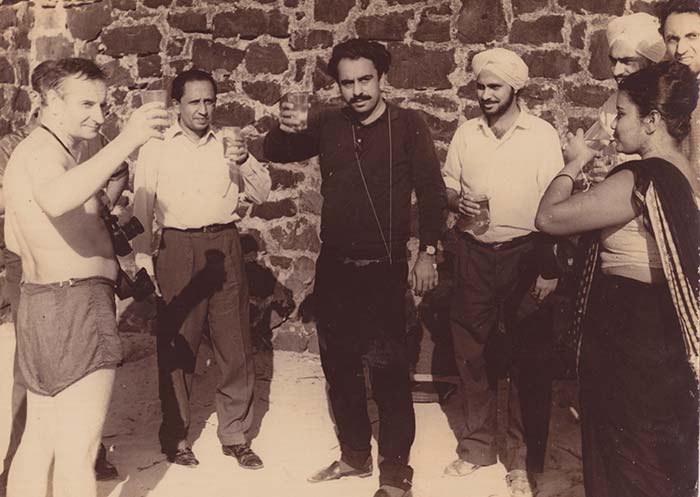

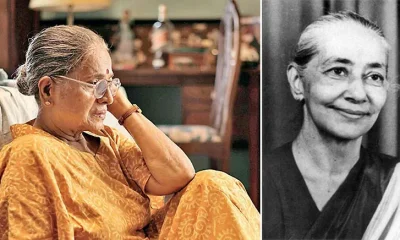

One of the defining auteurs of Sri Lankan cinema, Sumitra Peries made an indelible and enduring contribution to women’s filmmaking in South Asia.Satyajit Ray once reportedly called Lester James Peries, the Sri Lankan film director who passed away at the age of 99 in April 2018, his “only relation east of Suez.” Lester’s wife Sumitra, who was his closest colleague, and who passed away on 19 January 2023 at the age of 87, had her first encounter with Ray in Mexico in 1963.

By that point, Sumitra had returned from her studies in England and earned a reputation as an assistant director and editor. She recalled that Ray had been “kind and courteous”, but a little disdainful of her profession. When she told him of what she did, the Indian director had been somewhat unimpressed, comparing her work to that of a cutter. Temperamentally candid, Sumitra had fired back, “Well, I’m glad I’m not just a cutter!”

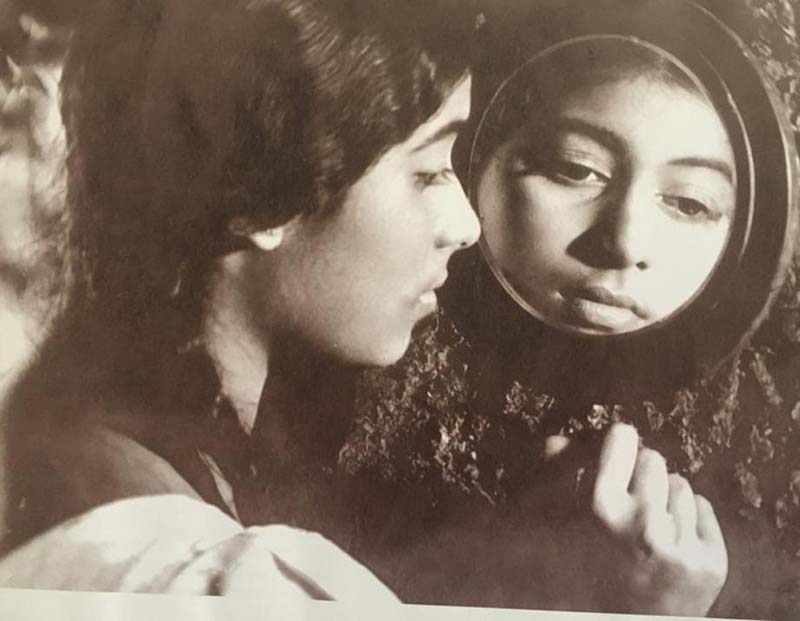

Sumitra Peries did not remain a cutter for long. After working on her husband’s films, she made her directorial debut in 1978 with Gehenu Lamayi (Girls). The film established the themes that would preoccupy her for the rest of her career: the rift between rich and poor, the torments of adolescent love, and most significantly, the agony of being a woman in Sri Lanka and in South Asia. Sumitra’s work thus clearly stands out in the pantheon of regional cinema, in ways that critics have so far not done justice to.

Sri Lanka has long been orientalised for its sandy beaches and its cultural sites. In the first half of the 20th century, the colonial government helped establish a local cinema in the capital, Colombo. The first Sri Lankan film, Kadawunu Poronduwa (Broken Promise), came out in 1947, a year before the country obtained its independence.From its inception, however, local films were derided as derivative, because they were shot abroad and were felt to be too artificial, contrived, and unauthentic.

Seeking a better and more grounded cinema, a group of Westernised, urban middle-class artistes moved into this void. The most prominent of them was Lester James Peries, who had worked for some time at the official propaganda arm of the Sri Lankan government, the Government Film Unit (GFU), and who had imbibed the aesthetics of Italian neo-realism and the British documentary. Peries’s first film, Rekava (1956), came out around the same time that Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali did in India. Like Ray’s film, it was lukewarmly received by local critics, but went on to establish the country on the world map.

Sumitra Peries subsequently established herself in this circle, but she came from a very different background. Born Sumitra Gunawardena on 24 March 1935, she hailed from a family of affluent arrack distillers on her mother’s side and a family of radical, socialist, and anti-imperialist activists on her father’s. Her two paternal uncles, Philip and Robert, had been actively involved in the struggle against British colonialism: a far cry from the middle-class, Westernised, and Anglicised milieu of her husband.

Born in the southwestern village of Payagala, Sumitra was raised in Avissawella, located roughly 30 miles from Colombo. Initially she was educated at the local school, St Mary’s College, where she mingled with her social peers as well as more deprived sections of her village. Though not part of an urban elite, her mother, Harriet Wickramasinghe, moved around in important circles, “playing tennis with her sari on.” In contrast to her two uncles, her father, Henry, adjusted to his wife’s milieu, “practising as a proctor.”

Sumitra’s earliest influence was her mother. Through a distillery that her own mother, or Sumitra’s grandmother, had set up, “she took responsibility for the family.” Sumitra’s father, on the other hand, “sought and went after less practical pursuits.”

Their social status did not limit their daughter’s social interactions. “We lived in the most basic of settings,” she remembered. “No electricity, no proper running water, certainly no attached bathrooms. Only through a small radio did we get to know of what was happening in the outside world. As such I would get out and meet other people, including the sons and daughters of estate workers. I revelled in these encounters.”

Colombo lay a world away from all this. When Sumitra turned 13, a month after Sri Lanka gained independence from Great Britain, her family decided to send her there to study. Her new home was to be at Gower Street, in Colombo 4. It was conveniently located right next to her new school, Visakha Vidyalaya, the island’s leading Buddhist girls’ school. “I took time to adjust to my new setting, but eventually got used to life in Colombo.”

Among her siblings, Sumitra was closest to her elder brother, Gamini or “Kuru.” When their mother died two years after they shifted to Colombo, he entered a long period of depression. “My brother was a very temperamental man. He left everything to us and left the country. We did not know where he was, or whether he planned to return.”

A few years later, he got in touch with Sumitra: he was in Malta, and he wanted her to join him. Though she was engaged with her higher studies, she heeded his call. She packed her belongings and soon boarded a P&O Liner. “I was not quite 21.”

At Malta, Sumitra joined her brother and a bohemian coterie of friends. Together they sailed across the Mediterranean, dropping anchor in the French Riviera. At Saint-Tropez near the Riviera, Sumitra spotted Brigitte Bardot and Roger Vadim filming And God Created Woman (1956). It was the first time she had seen a film being made.

By then she was at a loss: “I badly wanted to be a psychiatrist. My brother felt it would be best if I went to Switzerland, to study at the Jung Institute.”

Just as Sumitra was about to embark on her higher education, however, Gamini decided to return to Sri Lanka. “This led to a series of misadventures that ended in Paris. There I had a vague desire to settle in the Left Bank.” Fate, however, had other plans for her.

Sri Lanka had just established a Legation in Paris. The country’s Envoy, Vernon Mendis, got in touch with Sumitra and boarded her at his official residence. It was here, at the Legation, that she met Lester James Peries. “He told me to go to England and study film. He felt I was wasting my talents in Paris. Since I had nothing to lose, I heeded his advice.”

Sumitra enrolled herself at the London School of Film Technique (LSFT) in Brixton, the sole female in a class of white and middle-class males.

During her years at the LSFT, she grew very close to the filmmaker Lindsay Anderson, who taught her class. Lindsay had already met Lester a few years before. Needless to say, he and Sumitra became very good friends. Their association grew so strong that in her later visits to England, “we would meet, and he would cook for me.”

Sumitra successfully completed her studies. But finding a job was challenging. “Those days, if you weren’t a member of a union, it was not easy to enter the industry.”

Armed with her qualification, she knocked on the doors of Elizabeth Mai-Harris, one of Britain’s leading subtitling firms. “I passionately argued my case. Fortunately, they believed in me and took me in. My fluency in French may have helped.”

Sometime later, though, she encountered another problem: “I started growing homesick.” Her elder brother ordered her to return. She thus came back home.Sumitra then found work as an assistant to Lester Peries, onboard his film Sandesaya (The Message, 1960). “I was the sole female crew member. We were shooting a world away from Colombo. A tough ordeal for any woman, but I grew to enjoy it.”

She also grew close to Lester. Four years later, in 1964, she married him.

Making full use of her editing skills, Sumitra wound up as her husband’s closest aide. She worked on all his films in the 1960s: Gamperaliya (1963), Delovak Athara (1966), Ran Salu (1967), Golu Hadawatha (1968), and Akkara Paha (1969).

These films won awards and accolades abroad: Gamperaliya secured the Golden Peacock or the Best Film Award at the 3rd Indian International Film Festival and the Golden Head of Palenque at the Mexico Film Festival, while Ran Salu won the Gandhi Award at New Delhi and was telecast on Raidió Teilifís Éireann, Ireland.

Recalling her years as an editor, she once told me, “What fascinated me during these years was the mise-en-scène. To achieve the right cut is harder than you think. You need to train your eyes and you need to make the decision then and there.” Contrary to what Satyajit Ray may have felt, then, her job was hardly that of a mere cutter.

After a stint in France and a few idle years, Sumitra carved her path as director with Gehenu Lamai in 1978. Based on a popular novel, it became an instant success wherever it went: the British press in particular loved it, with David Robinson of The Times lauding it for its “holistic feminine sensibility.”

Its success emboldened her to make nine more films: Ganga Addara (By the Bank of the River, 1980), Yahalu Yeheli (Friends, 1982), Maya (1984), Sagara Jalaya Madi Handuwa Oba Sanda (A Letter Written in the Sand, 1988), Loku Duwa (The Eldest Daughter, 1994), Duwata Mawaka Misa (Mother Alone, 1997), Sakman Maluwa (The Pleasure Garden, 2003), Yahaluwo (Friends, 2007) and Vaishnavee (The Goddess, 2018).

Apart from her work in film, Sumitra also worked in television, having gained six months’ work experience at the French Radio and Television Institute (ORTF) in Paris in 1971. She served as Sri Lanka’s Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to France and Spain from 1995 to 1998, and did her part to secure international goodwill for the country at a time of rising ethnic tensions and separatist conflict.

With Yahaluwo and Vaishnavee behind her, she was toying with several ideas, as late as 2022, for her next venture. Humble to a fault, she remained open to outsiders, in particular young, aspiring directors who would constantly seek her advice.

Sumitra’s passing, given all this, signifies an end and a passing of an era. Linked through her husband to some of the most exciting strides in the arts of post-independence Sri Lanka, she nevertheless carved her own path. Indeed, as Vilasnee Tampoe-Hautin rightly argues in her biography, Sumitra Peries: Sri Lankan Filmmaker, while she is considered a mere appendage to her husband’s work, her career was distinct on its own right.

Moreover, unlike South Asian women filmmakers from her time – including Fatma Begum, Parveen Rizvi, Shamin Ara, Kohinoor Akhter, and Aparna Sen – she did not come to the director’s chair as an actress. In that sense Sumitra, with her education in the West, was a definitive precursor to the likes of Mira Nair and Deepa Mehta. This point has not yet been appreciated or acknowledged by historians of the regional cinema.

A product of a rural upper middle-class, Sumitra Peries remained intimately attached to her people, in particular women. Her films, which dwell considerably on their agonies and their torments, are in that sense an enduring testament, not just to her craft, but also to a bygone era in filmmaking – both in Sri Lanka and in South Asia.

Uditha Devapriya is a writer, researcher, and analyst based in Sri Lanka who contributes to a number of publications on topics such as history, art and culture, politics, and foreign policy. He can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com.

Features

An opportunity to move from promises to results

The local government elections, long delayed and much anticipated, are shaping up to be a landmark political event. These elections were originally due in 2023, but were postponed by the previous government of President Ranil Wickremesinghe. The government of the day even defied a Supreme Court ruling mandating that elections be held without delay. They may have feared a defeat would erode that government’s already weak legitimacy, with the president having assumed office through a parliamentary vote rather than a direct electoral mandate following the mass protests that forced the previous president and his government to resign. The outcome of the local government elections that are taking place at present will be especially important to the NPP government as it is being accused by its critics of non-delivery of election promises.

Examples cited are failure to bring opposition leaders accused of large scale corruption and impunity to book, failure to bring a halt to corruption in government departments where corruption is known to be deep rooted, failure to find the culprits behind the Easter bombing and failure to repeal draconian laws such as the Prevention of Terrorism Act. In the former war zones of the north and east, there is also a feeling that the government is dragging its feet on resolving the problem of missing persons, those imprisoned without trial for long periods and return of land taken over by the military. But more recently, a new issue has entered the scene, with the government stating that a total of nearly 6000 acres of land in the northern province will be declared as state land if no claims regarding private ownership are received within three months.

The declaration on land to be taken over in three months is seen as an unsympathetic action by the government with an unrealistic time frame when the land in question has been held for over 30 years under military occupation and to which people had no access. Further the unclaimed land to be designated as “state land” raises questions about the motive of the circular. It has undermined the government’s election campaign in the North and East. High-level visits by the President, Prime Minister, and cabinet ministers to these regions during a local government campaign were unprecedented. This outreach has signalled both political intent and strategic calculation as a win here would confirm the government’s cross-ethnic appeal by offering a credible vision of inclusive development and reconciliation. It also aims to show the international community that Sri Lanka’s unity is not merely imposed from above but affirmed democratically from below.

Economic Incentives

In the North and East, the government faces resistance from Tamil nationalist parties. Many of these parties have taken a hardline position, urging voters not to support the ruling coalition under any circumstances. In some cases, they have gone so far as to encourage tactical voting for rival Tamil parties to block any ruling party gains. These parties argue that the government has failed to deliver on key issues, such as justice for missing persons, return of military-occupied land, release of long-term Tamil prisoners, and protection against Buddhist encroachment on historically Tamil and Muslim lands. They make the point that, while economic development is important, it cannot substitute for genuine political autonomy and self-determination. The failure of the government to resolve a land issue in the north, where a Buddhist temple has been put up on private land has been highlighted as reflecting the government’s deference to majority ethnic sentiment.

The problem for the Tamil political parties is that these same parties are themselves fractured, divided by personal rivalries and an inability to form a united front. They continue to base their appeal on Tamil nationalism, without offering concrete proposals for governance or development. This lack of unity and positive agenda may open the door for the ruling party to present itself as a credible alternative, particularly to younger and economically disenfranchised voters. Generational shifts are also at play. A younger electorate, less interested in the narratives of the past, may be more open to evaluating candidates based on performance, transparency, and opportunity—criteria that favour the ruling party’s approach. Its mayoral candidate for Jaffna is a highly regarded and young university academic with a planning background who has presented a five year plan for the development of Jaffna.

There is also a pragmatic calculation that voters may make, that electing ruling party candidates to local councils could result in greater access to state funds and faster infrastructure development. President Dissanayake has already stated that government support for local bodies will depend on their transparency and efficiency, an implicit suggestion that opposition-led councils may face greater scrutiny and funding delays. The president’s remarks that the government will find it more difficult to pass funds to local government authorities that are under opposition control has been heavily criticized by opposition parties as an unfair election ploy. But it would also cause voters to think twice before voting for the opposition.

Broader Vision

The government’s Marxist-oriented political ideology would tend to see reconciliation in terms of structural equity and economic justice. It will also not be focused on ethno-religious identity which is to be seen in its advocacy for a unified state where all citizens are treated equally. If the government wins in the North and East, it will strengthen its case that its approach to reconciliation grounded in equity rather than ethnicity has received a democratic endorsement. But this will not negate the need to address issues like land restitution and transitional justice issues of dealing with the past violations of human rights and truth-seeking, accountability, and reparations in regard to them. A victory would allow the government to act with greater confidence on these fronts, including possibly holding the long-postponed provincial council elections.

As the government is facing international pressure especially from India but also from the Western countries to hold the long postponed provincial council elections, a government victory at the local government elections may speed up the provincial council elections. The provincial councils were once seen as the pathway to greater autonomy; their restoration could help assuage Tamil concerns, especially if paired with initiating a broader dialogue on power-sharing mechanisms that do not rely solely on the 13th Amendment framework. The government will wish to capitalize on the winning momentum of the present. Past governments have either lacked the will, the legitimacy, or the coordination across government tiers to push through meaningful change.

Obtaining the good will of the international community, especially those countries with which Sri Lanka does a lot of economic trade and obtains aid, India and the EU being prominent amongst these, could make holding the provincial council elections without further delay a political imperative. If the government is successful at those elections as well, it will have control of all three tiers of government which would give it an unprecedented opportunity to use its 2/3 majority in parliament to change the laws and constitution to remake the country and deliver the system change that the people elected it to bring about. A strong performance will reaffirm the government’s mandate and enable it to move from promises to results, which it will need to do soon as mandates need to be worked at to be long lasting.

by Jehan Perera

Features

From Tank 590 to Tech Hub: Reunited Vietnam’s 50-Year Journey

The fall of Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City – HCM) on 30 April 1975 marked the end of Vietnam’s decades-long struggle for liberation—first against French colonialism, then U.S. imperialism. Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh, formed in 1941, fought Japanese occupiers and later defeated France at Dien Bien Phu (1954). The Geneva Accords temporarily split Vietnam, with U.S.-backed South Vietnam blocking reunification elections and reigniting conflict.

The fall of Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City – HCM) on 30 April 1975 marked the end of Vietnam’s decades-long struggle for liberation—first against French colonialism, then U.S. imperialism. Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh, formed in 1941, fought Japanese occupiers and later defeated France at Dien Bien Phu (1954). The Geneva Accords temporarily split Vietnam, with U.S.-backed South Vietnam blocking reunification elections and reigniting conflict.

The National Liberation Front (NLF) led resistance in the South, using guerrilla tactics and civilian support to counter superior U.S. firepower. North Vietnam sustained the fight via the Ho Chi Minh Trail, despite heavy U.S. bombing. The costly 1968 Tet Offensive exposed U.S. vulnerabilities and shifted public opinion.

Of even more import, the Vietnam meat-grinder drained the U.S. military machine of weapons, ammunition and morale. By 1973, relentless resistance forced U.S. withdrawal. In March 1975, the Vietnamese People’s Army started operations in support of the NLF. The U.S.-backed forces collapsed, and by 30 April the Vietnamese forces forced their way into Saigon.

At 11 am, Soviet-made T-54 tank no. 843 of company commander Bui Quang Than rammed into a gatepost of the presidential palace (now Reunification Palace). The company political commissar, Vu Dang Toan, following close behind in his Chinese-made T-59 tank, no. 390, crashed through the gate and up to the palace. It seems fitting that the tanks which made this historic entry came from Vietnam’s principal backers.

Bui Quang Than bounded from his tank and raced onto the palace rooftop to hoist the NLF flag. Meanwhile, Vu Dang Toan escorted the last president of the U.S.-backed regime, Duong Van Minh, to a radio station to announce the surrender of his forces. This surrender meant the liberation not only of Saigon but also of the entire South, the reunification of the country, and a triumph of perseverance—a united, independent nation free from foreign domination after a 10,000-day war.

Celebrations

On 30 April 2025, Vietnam celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Liberation of the South and National Reunification. HCM sprouted hundreds of thousands of national flags and red hammer-and-sickle banners, complemented by hoardings embellished with reminders of the occasion – most of them featuring tank 590 crashing the gate.

Thousands of people camped on the streets from the morning of 29 April, hoping to secure good spots to watch the parade. Enthusiasm, especially of young people, expressed itself by the wide use of national flag t-shirts, ao dais (traditional long shirts over trousers), conical hats, and facial stickers. This passion may reflect increasing prosperity in this once impoverished land.

The end of the war found Vietnam one of the poorest countries in the world, with a low per capita income and widespread poverty. Its economy struggled due to a combination of factors, including wartime devastation, a lack of foreign investment and heavy reliance on subsistence agriculture, particularly rice farming, which limited its potential for growth. Western sanctions meant Vietnam relied heavily on the Soviet Union and its socialist allies for foreign trade and assistance.

The Vietnamese government launched Five-Year Plans in agriculture and industry to recover from the war and build a socialist nation. While encouraging family and collective economies, it restrained the capitalist economy. Despite these efforts, the economy remained underdeveloped, dominated by small-scale production, low labour productivity, and a lack of modern technology. Inflexible central planning, inept bureaucratic processes and corruption within the system led to inefficiencies, chronic shortages of goods, and limited economic growth. As a result, Vietnam’s economy faced stagnation and severe hyperinflation.

These mounting challenges prompted the Communist Party of Vietnam to introduce Đổi Mới (Renovation) reforms in 1986. These aimed to transition from a centrally planned economy to a “socialist-oriented market economy” to address inefficiencies and stimulate growth, encouraging private ownership, economic deregulation, and foreign investment.

Transformation

Đổi Mới marked a historic turning point, unleashing rapid growth in agricultural output, industrial expansion, and foreign direct investment. Early reforms shifted agriculture from collective to household-based production, encouraged private enterprise, and attracted foreign investment. In the 2000s, Vietnam became a top exporter of textiles, electronics, and rice, shifting towards high-tech manufacturing (inviting Samsung and Intel factories). By the 2020s, it emerged as a global manufacturing hub, the future focus including the digital economy, green energy, and artificial intelligence.

In less than four decades, Vietnam transformed from a poor, agrarian nation into one of Asia’s fastest-growing economies, though structural reforms are still needed for sustainable development. Growth has remained steady, at 5-8% per year.

Vietnam’s reforms lifted millions out of poverty, created a dynamic export-driven economy, and improved education, healthcare, and infrastructure. This has manifested itself in reducing extreme poverty from 70% to 1%, increasing literacy to 96%, life expectancy from 63 to 74 years, and rural electrification from less than 50% to 99.9%. Industrialisation drove urbanisation, which doubled from 20% in 1986 to 40% now.

This change displayed itself during the celebrations in HCM, amid skyscrapers, highways and the underground metro system. Everybody dressed well, and smartphones could be seen everywhere – penetration has reached three-fourths of the population. Thousands turned out on motorbikes and scooters (including indigenous electric scooters) – two-wheeler ownership is over 70%, the highest rate per capita in ASEAN. Traffic jams of mostly new cars emphasised the growth of the middle class.

At the same time, street food vendors and makeshift pavement bistro owners joined sellers of patriotic hats, flags and other paraphernalia to make a killing from the revellers. This reflects the continuance of the informal sector– currently representing 30% of the economy.

The Vietnamese government channelled tax income from booming sectors into underdeveloped regions, investing in rural infrastructure and social welfare to balance growth and mitigate urban-rural inequality during rapid economic expansion. Nevertheless, this economic transformation came with unequal benefits, exacerbating income inequality and persistent gender gaps in wages and opportunities. Sustaining growth requires tackling corruption, upgrading workforce skills, and balancing development with inequality.

NLF flag

Tank 390 courtesy Bao Hai Duong

The parade itself, meticulously carried out (having been rehearsed over three days), featured cultural pageants and military displays and drew admiration. Of special note, the inclusion of foreign military contingents from China, Laos, and Cambodia for the first time signalled greater regional solidarity, acknowledging their historical support while maintaining a balanced foreign policy approach.

Veteran, war-era foreign journalists noted another interesting fact: the re-emergence of the NLF flag. Comprising red and blue stripes with a central red star, this flag had never been prominent at the ten-year anniversary celebrations. The journalists questioned its sudden reappearance. It may be to give strength to the idea of the victory being one of the South itself, part of a drive to increase unity between North and South.

Before reunification in 1975, North and South Vietnam embodied starkly contrasting economic and social models. The North operated under a centrally planned socialist system, with collectivised farms and state-run industries. It emphasised egalitarianism, mass education, and universal healthcare while actively preserving traditional Vietnamese culture. The South, by contrast, maintained a market-oriented economy heavily reliant on agricultural exports (rice and rubber) and foreign aid. A wealthy elite dominated politics and commerce, while Western—particularly American—cultural influence grew pervasive during the war years.

Following reunification under the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (1976), the government moved swiftly to integrate the two regions. In 1978, it introduced a unified national currency (the đồng, VND), merging the North’s and South’s financial systems into a single, state-controlled framework. The unification of monetary policy symbolised the broader ideological project: to erase colonial and capitalist legacies.

Unity and solidarity

However, the economic disparities and cultural divides between regions persist, though less pronounced than before. The South, particularly HCM, remains Vietnam’s economic powerhouse, with a stronger private sector and international trade connections. The North, including Hanoi, has a more government-driven economy. Southerners tend to have a more entrepreneurial mindset, while Northerners are often seen as more traditional and rule-bound. Conversely, individuals from the North occupy more key government positions.

Studies suggest that people in the South exhibit lower trust in the government compared to those in the North. HCM tends to have stronger support for Western countries like the United States, while Hanoi has historically maintained closer ties with China. People in HCM tend to use the old “Saigon” city name.

Consequently, the 50th anniversary celebrations saw a focus on reconciliation and unity, reflecting a shift in perspective towards peace and friendship, as well as accompanying patriotism with international solidarity.

The exuberant crowds, modern infrastructure, and thriving consumer economy showcased the transformative impact of Đổi Mới—yet lingering regional disparities, informal labour challenges, and unequal gains remind the nation that sustained progress demands inclusive reforms. The symbolic return of the NLF flag and the emphasis on unity underscored a nuanced reconciliation between North and South, honouring shared struggle while navigating enduring differences.

As Vietnam strides forward as a rising Asian economy, it balances its socialist legacy with global ambition, forging a path where prosperity and patriotism converge. The anniversary was not just a celebration of the past but a reflection on the complexities of Vietnam’s ongoing evolution.

(Vinod Moonesinghe read mechanical engineering at the University of Westminster, and worked in Sri Lanka in the tea machinery and motor spares industries, as well as the railways. He later turned to journalism and writing history. He served as chair of the Board of Governors of the Ceylon German Technical Training Institute. He is a convenor of the Asia Progress Forum, which can be contacted at asiaprogressforum@gmail.com.)

By Vinod Moonesinghe

Features

Hectic season for Rohitha and Rohan and JAYASRI

The Sri Lanka music scene is certainly a happening place for quite a few of our artistes, based abroad, who are regularly seen in action in our part of the world. And they certainly do a great job, keeping local music lovers entertained.

The Sri Lanka music scene is certainly a happening place for quite a few of our artistes, based abroad, who are regularly seen in action in our part of the world. And they certainly do a great job, keeping local music lovers entertained.

Rohitha and Rohan, the JAYASRI twins, who are based in Vienna, Austria, are in town, doing the needful, and the twosome has turned out to be crowd-pullers.

Says Rohitha: Our season here in Sri Lanka, and summer in the south hemisphere (with JAYASRI) started in October last year, with many shows around the island, and tours to Australia, Japan, Dubai, Doha, the UK, and Canada. We will be staying in the island till end of May and then back to Austria for the summer season in Europe.”

Rohitha mentioned their UK visit as very special.

The JAYASRI twins Rohan and Rohitha

“We were there for the Dayada Charity event, organised by The Sri Lankan Kidney Foundation UK, to help kidney patients in Sri Lanka, along with Yohani, and the band Flashback. It was a ‘sold out’ concert in Leicester.

“When we got back to Sri Lanka, we joined the SL Kidney Foundation to handover the financial and medical help to the Base Hospital Girandurukotte.

“It was, indeed, a great feeling to be a part of this very worthy cause.”

Rohitha and Rohan also did a trip to Canada to join JAYASRI, with the group Marians, for performances in Toronto and Vancouver. Both concerts were ‘sold out’ events.

They were in the Maldives, too, last Saturday (03).

Alpha Blondy:

In action, in

Colombo, on

19th July!

JAYASRI, the full band tour to Lanka, is scheduled to take place later this year, with Rohitha adding “May be ‘Another legendary Rock meets Reggae Concert’….”

The band’s summer schedule also includes dates in Dubai and Europe, in September to Australia and New Zealand, and in October to South Korea and Japan.

Rohitha also enthusiastically referred to reggae legend Alpha Blondy, who is scheduled to perform in Sri Lanka on 19th July at the Air Force grounds in Colombo.

“We opened for this reggae legend at the Austria Reggae Mountain Festival, in Austria. His performance was out of this world and Sri Lankan reggae fans should not miss his show in Colombo.”

Alpha Blondy is among the world’s most popular reggae artistes, with a reggae beat that has a distinctive African cast.

Calling himself an African Rasta, Blondy creates Jah-centred anthems promoting morality, love, peace, and social consciousness.

With a range that moves from sensitivity to rage over injustice, much of Blondy’s music empathises with the impoverished and those on society’s fringe.

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoOTRFU Beach Tag Rugby Carnival on 24th May at Port City Colombo

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoRanil’s Chief Security Officer transferred to KKS

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoRemembering Dr. Samuel Mathew: A Heart that Healed Countless Lives

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoThe Broken Promise of the Lankan Cinema: Asoka & Swarna’s Thrilling-Melodrama – Part IV

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoTrump tariffs and their effect on world trade and economy with particular

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoRadisson Blu Hotel, Galadari Colombo appoints Marko Janssen as General Manager

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoCCPI in April 2025 signals a further easing of deflationary conditions

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoA piece of home at Sri Lankan Musical Night in Dubai