Features

Our Common Heritage One country – one land – one people

By Ashley de Vos

(Continued from yesterday’s Midweek Review)

It was King Senerath the Sinhala King, in the 16th C, who transported 4,000 followers of Islam from the west coast and settled them on the east coast to save them from being routed, eliminated and even annihilated by the aggressive Portuguese. The east coast Muslims share this common ancestry. The assimilation into the general cultural matrix has been stifled by a ghetto mentality that grew out of a mindset where the women felt more secure in a ghetto, while the men were out trading. This is clearly seen in Katankudi and other such areas in the coastal zone.

Five Portuguese who wished to settle in the island free from Dutch discrimination, approached the Sinhala King and requested protection from the Dutch. There were Catholic priests in the Kandy court, who helped the King to correspond with the King of Portugal in the Portuguese language, and hence access was easy. The benevolent King invited these ex- soldiers and gave them a presumably disused Buddhist monastery to settle in. Their offspring who settled in the surrounding lands are proud of this ancestry. The Siripathula votive slab from the earliest Anuradhapura period that belonged to this early monastery, was still there at the site, when it was visited in late 2005. This area referred to as Wahakotte is today a major pilgrim destination for the Catholic community.

During the British colonial occupation of the island and into independence, those inhabiting the coastal areas of the country, who had already cohabited closely with the Portuguese, the Dutch and the British, had favoured access to the ownership of lands. They felt superior on learnt caste lines, and were soon encouraged to participate in new professions. Their children had easy access to an English education, facilitated by a group of committed Christian Missionaries. This helped them to gain ready admission to the prestigious British universities and professions and in turn, to corner all the prized jobs offered by the British administration.

Those who benefitted from a missionary education, even from the north of the island moved to the metropolis Colombo in search of their fortunes. They built palatial dwellings, many from the north even married Sinhala women and relegated Jaffna that far off place, as a resting place to keep their older relations. The journey to Jaffna became less frequent.

If this is one country, every citizen has the right to live and work wherever they wish, and this has been amply demonstrated in the past. Sri Lankans should be afforded the privilege to live, work and purchase property wherever they decide even if it means enacting special legislation to facilitate this process. Why the special privilege only for some?

J.T Ratnam states that “some of the wealthiest Tamils came from Manipay. Most of them left their palatial buildings untenanted or in charge of some poor relation in order to reside and work in the metropolis. They returned home finally only in their old age, this was the rule.” (Jane Russell). Most professionals from the north, totally neglected Jaffna and instead concentrated all personal development on Colombo and other centres that were conducive to their chosen line of work. Prompting R.W. Crossette-Thambiah to record that “it was the Tamils living in Colombo who had the money and the prestige to become leaders in Jaffna” (Jane Russell). Many were reinforced by dowry wealth infused by the Malaysian pensioners.

These professionals who left the north to settle in the south should take some responsibility for all that happened in the north in the past 70 years. In fact, the later youth uprising was against the severe communal caste based hierarchy, disorientation and governed by an acquired strong caste difference that was forcibly perpetrated in the north. According to Jaffna Superintendent of Police, R. Sundaralingam, it was controlled by a neo-colonial Vellahla elite. In the Maviddapuram Temple dispute it included, even at times, beating of the lower castes with heavy Palmyra walking sticks, on any attempt to enter the controlled temple premises.

One always believed that the Gods had a widespread benevolence to encompass all groups of people, irrespective of status in life, but it seems that man has changed the paradigm to suit his own narrow desires.

Having enjoyed the benefits that an English education offered them, the English educated population remained silent when the larger Sinhala population was kept down for centuries by the three colonial powers, even castigated by the newly elevated caste groups in the south, who owned lands. They enjoyed all the perks that fell off the colonial table. As many of these people were far removed from their roots, they joined in the protest, when this large silent population was given a voice.

Those who criticised the new voice were mostly those who had enjoyed a privileged English education. Another marginalised group who may or may not have enjoyed the interlude, felt cheated; they left for greener pastures to Australia, the UK and Canada. Unfortunately, this generation continues to live in a time warp centred on the 1960s, craving for the good times and feeding on the special food types they had grown up with.

The same criticism is still flaunted as the reason for the plight Sri Lanka finds itself in today although many fingers could point in many directions. Many successful countries who had and still have a pride in their own heritage and culture have survived; they learned their mother tongue well and learned the colonial tongue later in life to become world leaders in their chosen fields.

What happened in Sri Lanka? The “Kaduwa” is nothing but the affluent English speakers laughing at the down trodden majority if they were to make a mistake in the use of the colonial foreign language.

Tourism has created a new generation that is able to converse in many foreign languages; they learnt the language with the help of the tourists who corrected them if they made mistakes, and they were never ridiculed or laughed at. Whether to sing alternate verses of the national anthem, or the whole in two languages, is not a great debate.

Sri Lanka has a flag, the only one in the world that celebrates pronounced ethnic division, a precise notification with a late beginning. Should we not change and go back to the flag originally hoisted at independence, this especially, as we all share a common heritage.

Much is discussed about the persons who have disappeared during the war, this recurrent issue, this wound, is kept ever festered, by generous NGO funding and is used as a clarion call to win sympathy especially when foreign dignitaries surreptitiously or otherwise visit the North of the island. Except for this controlled group, nothing is heard of the many more Tamil politicians, civil officers, lecturers, teachers, ordinary citizens and the hundreds of Tamil youth who were eliminated by the LTTE in the north, where is the regress for them? They have mothers as well?

Less is heard of the 800 or 900 policemen who were forced by the leadership of the day to surrender to the LTTE. They all vanished into thin air, a trick Houdini would have given an arm and a leg to learn. The 1,000 odd IPKF soldiers who were killed; where are their bodies? An IPKF battalion that went astray and never came back; the 5,000 odd Sri Lankan soldiers are still missing. The hundreds who were eliminated in the “border” villages, in the North Central Province, on roads, in buses, in the numerous bomb blasts. My friend, the charismatic Cedric Martinstyne, where is he, who was responsible?

The thousands of young men and women went missing in 1971 and the thousands of young men and women tortured and burnt on the roadside in 1988 – 89. They were all human; they had families, mothers and fathers, sisters and brothers, and some even had children. Why is no one talking about them? Is it only fashionable to follow the International NGO gravy train?

The solution for facilitating and encouraging the sustainable development of a common heritage as a single country is simply to legislate and ban, and remove politicians or parties that survive on highlighting ethnicity, hatred and religious bias from the equation and instead introduce a new breed of specially identified benevolent technocrats chosen for their capability. Certainly not chosen from a group that has volunteered on the basis that they think, yes, they arrogantly think, they have the solutions to all the problems the country is faced with.

This will only lead to disaster, for a benevolent leadership.

The technocrats should be chosen after a careful and diligent head hunt to identify the most suitable and proven individual who is not only capable but also cares for and has a commitment to this country first. With a willingness to give all up to deliberate and run the engines of this country as patriots. But beware the arrogance of these espiocrats. They may need further education and training at a staff college on a holistic vision on where Sri Lanka would like to be in fifty years in the future.

Those representing Sri Lanka at the world stage should be focussed, well briefed, brave enough to stand tall and committed to the wellbeing of the country only, first, and should not be made up of the agenda driven dealers who are willing to compromise to be in the good books of foreigners with devious plans or to satisfy their personal ends: there are many such individuals around. These chosen technocrats with special abilities should be carefully nurtured. Running Sri Lanka, a country of twenty million, is not an insurmountable task; it requires honesty, discipline and commitment only. Across the pond, Mumbai is a city state of eighteen million run by a mayor and a council.

Unfortunately, in Sri Lanka, there are too many incongruous layers of superfluous repetition and astronomical cost escalation to satisfy mediocracy with their never ending assiduous demands and perks. It has now become a livelihood worth killing for. Much of it forced on us by the 13th Amendment, purposely introduced by India. The cunning “Big Brother Gift”, knowing full well that if implemented, Sri Lanka would never ever recover. This would always remain to the advantage of the hegemony of the subcontinent. We have witnessed the repercussions. This is where most of the support for the corruption stems from.

In the historical period, the kings did not administer the people; the village heads did and their word was respected and obeyed. No one from outside decided for the village. The responsibility of the king lay with ensuring that the unique irrigation system was protected and enhanced, secondly, there was protection for Buddhism, respect for other people and their beliefs, the continuation of the natural Sinhalisation process and most importantly, it was to ensure, the security of the people and the country from foreign invasions.

Kings who had an interest in Ayurveda planted the Aralu, Bulu, Nelli forests in the hope that someone, someday, may benefit from them. Our new guardians and extended families instead enjoy cutting the forests for personal gains, thereby, threatening the future water security of the whole nation and the biodiversity in the forests.

The holistic security of a country should always be decided only by the local security experts concerned, not by selfish emotional considerations by a group in a district, or by foreign “experts”. The security of a nation requires careful study and strategic understanding of the possible threats and with major contributions by the three forces charged with securing the country from illegal immigration and any other internal or external threats.

While there may be an argument that war technology has changed and that it calls for restricting the location of camps. The locations of the camps, even if it meant acquiring land, should be done according to a carefully studied, but strict pattern that suits the country concerned and not to suit “External War Consultants”. There are examples of a thousand bases placed by waring nations around the world in locations far removed from the countries concerned. Some through invitation, some located by way of war booty. All of them follow a single pattern.

Sri Lanka should avoid falling into providing a ready gateway to such a pattern. It should also stay away from agreeing to draconian treaties and agreements like the MCC and other related documents on the cheap, at totally discounted rates, only $90 Million a year for five years, permitting unlimited access to the use of the country under their own terms and rules. Sri Lanka is not for sale. What is implied in these documents are detrimental to the generations to come and would be regarded by them as acts of treason against an innocent people.

We the people need guidance by example; we don’t require a supercilious individual to tell us what to do, especially to interfere with the natural action of reconciliation and interaction, of coming together again, a progression that is usually built on mutual trust, an activity that the self-centred politician wilfully and constantly interfere with. From earliest times Buddhists and Hindus shared a common understanding,; this was to concretise in the 14th C after King Bhuvanakabahu introduced the shrine of God Vishnu as the protector of Buddhism into the temple complex.

Today, every Buddhist temple has a Vishnu shrine incorporated at the entrance, in a mutual respect for all. Unfortunately, fundamental Hinduism is raising its head for the first time on the island in the guise of the “Ramayana Trails” that was commenced by a desperate and irresponsible tourism industry. Will it lead to the building of a myriad of new shrines to Hindu Gods and Goddesses to commemorate events in fictitious locations is to be seen. A development that will host fundamental Hinduism, a progression this island could do without.

The people of this island, as a group of intelligent, enlightened humans, are capable of eliminating the years of induced suspicion that has been created by these self-centred politicians. The people can and will sort it out. These politicians should be kept away as they are more of an irritant, a hindrance to real reconciliation and a selfish, destructive element in nation building.

The unnatural rush, corona or no corona, to submit nominations for a future election, shows the unusual zeal in the rush to collect the spoils. Thereafter most applicants went into hibernation, to hell with the constituents. This is sensed, suffered and remarked on by the long suffering farming community who commented that they saw the people’s representatives only just before an election. These farmers should be trusted and looked after. Instead they are forced to sit on heaps of rotting vegetables and face the unscrupulous money lenders, head on.

Eventually, it is a scientific approach to agriculture that will save this country, not urbanisation and its proliferation of partner industry. If you don’t have markets, you cannot eat the products your industry will roll off the production line. But as proved by “Coronavirus” vegetables and fruit, you can.

Let reconciliation happen the way it should, a slow but sure natural process. As Sri Lanka moves forward, she deserves to be free of worthless heavy shackles. Let’s relegate them to the trash heap of history.

Features

When floods strike: How nations keep food on the table

Insights from global adaptation strategies

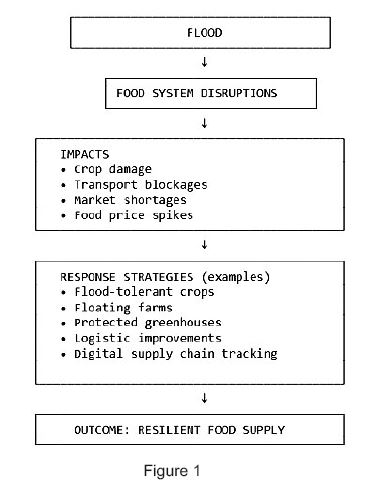

Sri Lanka has been heavily affected by floods, and extreme flooding is rapidly becoming one of the most disruptive climate hazards worldwide. The consequences extend far beyond damaged infrastructure and displaced communities. The food systems and supply networks are among the hardest hit. Floods disrupt food systems through multiple pathways. Croplands are submerged, livestock are lost, and soils become degraded due to erosion or sediment deposition. Infrastructural facilities like roads, bridges, retail shops, storage warehouses, and sales centres are damaged or rendered inaccessible. Without functioning food supply networks, even unaffected food-producing regions struggle to continue daily lives in such disasters. Poor households, particularly those dependent on farming or informal rural economies, face sharp food price increases and income loss, increasing vulnerability and food insecurity.

Many countries now recognie that traditional emergency responses alone are no longer enough. Instead, they are adopting a combination of short-term stabilisation measures and long-term strategies to strengthen food supply chains against recurrent floods. The most common immediate response is the provision of emergency food and cash assistance. Governments, the World Food Programme, and other humanitarian organisations often deliver food, ready-to-eat rations, livestock feed, and livelihood support to affected communities.

Alongside these immediate measures, some nations are implementing long-term strategic actions. These include technology- and data-driven approaches to improve flood preparedness. Early warning systems, using satellite data, hydrological models, and advanced weather forecasting, allow farmers and supply chain operators to prepare for potential disruptions. Digital platforms provide market intelligence, logistics updates, and risk notifications to producers, wholesalers, and transporters. This article highlights examples of such strategies from countries that experience frequent flooding.

China: Grain Reserves and Strategic Preparedness

China maintains a large strategic grain reserve system for rice, wheat, and maize; managed by NFSRA-National Food and Strategic Reserves Administration and Sinograin (China Grain Reserves Corporation (Sinograin Group), funded by the Chinese government, that underpins national food security and enables macro-control of markets during supply shocks. Moreover, improvements in supply chain digitization and hydrological monitoring, the country has strengthened its ability to maintain stable food availability during extreme weather events.

Bangladesh: Turning Vulnerability into Resilience

In recent years, Bangladesh has stood out as one of the world’s most flood-exposed countries, yet it has successfully turned vulnerability into adaptive resilience. Floating agriculture, flood-tolerant rice varieties, and community-run grain reserves now help stabilise food supplies when farmland is submerged. Investments in early-warning systems and river-basin management have further reduced crop losses and protected rural livelihoods.

Netherlands, Japan: High-Tech Models of Flood Resilience

The Netherlands offers a highly technical model. After catastrophic flooding in 1953, the country completely redesigned its water governance approach. Farmland is protected behind sea barriers, rivers are carefully controlled, and land-use zoning is adaptive. Vertical farming and climate-controlled greenhouses ensure year-round food production, even during extreme events. Japan provides another example of diversified flood resilience. Following repeated typhoon-induced floods, the country shifted toward protected agriculture, insurance-backed farming, and automated logistics systems. Cold storage networks and digital supply tracking ensure that food continues to reach consumers, even when roads are cut off. While these strategies require significant capital and investment, their gradual implementation provides substantial long-term benefits.

Pakistan, Thailand, Indonesia, and Vietnam: Reform in Response to Recurrent Floods

In contrast, Pakistan and Thailand illustrate both the consequences of climate vulnerability and the benefits of proactive reform. The 2022 floods in Pakistan submerged about one-third of the country, destroying crops and disrupting trade networks. In response, the country has placed greater emphasis on climate-resilient farming, water governance reforms, and satellite-based crop monitoring. Pakistan as well as India is promoting crop diversification and adjusting planting schedules to help farmers avoid the peak monsoon flood periods.

Thailand has invested in flood zoning and improved farm infrastructure that keep markets supplied even during severe flooding. Meanwhile, Indonesia and Vietnam are actively advancing flood-adapted land-use planning and climate-resilient agriculture. For instance, In Vietnam’s Mekong Delta, pilot projects integrate flood-risk mapping, adaptive cropping strategies, and ecosystem-based approaches to reduce vulnerability in agricultural and distribution areas. In Indonesia, government-supported initiatives and regional projects are strengthening flood-risk-informed spatial planning, adaptive farming practices, and community-based water management to improve resilience in flood-prone regions. (See Figure 1)

The Global Lesson: Resilience Requires Early Investment

The Global Lesson: Resilience Requires Early Investment

The global evidence is clear: countries that invest early in climate-adaptive agriculture and resilient logistics are better able to feed their populations, even during extreme floods. Building a resilient future depends not only on how we grow food but also on how we protect, store, and transport it. Strengthening infrastructure is therefore central to stabilising food supply chains while maintaining food quality, even during prolonged disruptions. Resilient storage systems, regional grain reserves, efficient cold chains, improved farming infrastructure, and digital supply mapping help reduce panic buying, food waste, and price shocks after floods, while ensuring that production capacity remains secure.

Persistent Challenges

However, despite these advances, many flood-exposed countries still face significant challenges. Resources are often insufficient to upgrade infrastructure or support vulnerable rural populations. Institutional coordination across the agriculture, disaster management, transport, and environmental sectors remains weak. Moreover, the frequency and scale of climate-driven floods are exceeding the design limits of older disaster-planning frameworks. As a result, the gap between exposure and resilience continues to widen. These challenges are highly relevant to Sri Lanka as well and require deliberate, gradual efforts to phase them out.

The Role of International Trade and global markets

When domestic production falls in such situations, international trade serves as an important buffer. When domestic production is temporarily reduced, imports and regional trade flows can help stabilise food availability. Such examples are available from other countries. For instance, In October 2024, floods in Bangladesh reportedly destroyed about 1.1 million tonnes of rice. In response, the government moved to import large volumes of rice and allowed accelerated or private-sector imports of rice to stabilize supply and curb food price inflation. This demonstrates how, when domestic production fails, international trade/livestock/food imports (from trade partners) acted as a crucial buffer to ensure availability of staple food for the population. However, this approach relies on well-functioning global markets, strong diplomatic relationships, and adequate foreign exchange, making it less reliable for economically fragile nations. For example, importing frozen vegetables to Sri Lanka from other countries can help address supply shortages, but considerations such as affordability, proper storage and selling mechanisms, cooking guidance, and nutritional benefits are essential, especially when these foods are not widely familiar to local populations.

Marketing and Distribution Strategies during Floods

Ensuring that food reaches consumers during floods requires innovative marketing and distribution strategies that address both supply- and demand-side challenges. Short-term interventions often include direct cash or food transfers, mobile markets, and temporary distribution centres in areas where conventional marketplaces become inaccessible. Price stabilisation measures, such as temporary caps or subsidies on staple foods, help prevent sharp inflation and protect vulnerable households. Awareness campaigns also play a role by educating consumers on safe storage, cooking methods, and the nutritional value of unfamiliar imported items, helping sustain effective demand.

Some countries have integrated technology to support these efforts; in this regard, adaptive supply chain strategies are increasingly used. Digital platforms provide farmers, wholesalers, and retailers with real-time market information, logistics updates, and flood-risk alerts, enabling them to reroute deliveries or adjust production schedules. Diversified delivery routes, using alternative roads, river transport, drones, or mobile cold-storage units, have proven essential for maintaining the flow of perishable goods such as vegetables, dairy, and frozen products. A notable example is Japan, where automated logistics systems and advanced cold-storage networks help keep supermarkets stocked even during severe typhoon-induced flooding.

The Importance of Research, Coordination, and Long-Term Commitment

Global experience also shows that research and development, strong institutional coordination, and sustained national commitment are fundamental pillars of flood-resilient food systems. Countries that have successfully reduced the impacts of recurrent floods consistently invest in agricultural innovation, cross-sector collaboration, and long-term planning.

Awareness Leads to Preparedness

As the summary, global evidence shows that countries that act early, plan strategically, and invest in resilience can protect both people and food systems. As Sri Lanka considers long-term strategies for food security under climate change, learning from flood-affected nations can help guide policy, planning, and public understanding. Awareness is the first step which preparedness must follow. These international experiences offer valuable lessons on how to protect food systems through proactive planning and integrated actions.

(Premaratne (BSc, MPhil, LLB) isSenior Lecturer in Agricultural Economics Department of Agricultural Systems, Faculty of Agriculture, Rajarata University. Views are personal.)

Key References·

Cabinet Secretariat, Government of Japan, 2021. Fundamental Plan for National Resilience – Food, Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries / Logistics & Food Supply Chains. Tokyo: Cabinet Secretariat.

· Delta Programme Commissioner, 2022. Delta Programme 2023 (English – Print Version). The Hague: Netherlands Delta Programme.

· Hasanuddin University, 2025. ‘Sustainable resilience in flood-prone rice farming: adaptive strategies and risk-sharing around Tempe Lake, Indonesia’, Sustainability. Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/17/6/2456 [Accessed 3 December 2025].

· Mekong Urban Flood Resilience and Drainage Programme (TUEWAS), 2019–2021. Integrated urban flood and drainage planning for Mekong cities. TUEWAS / MRC initiative.

· Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, People’s Republic of China, 2025. ‘China’s summer grain procurement surpasses 50 mln tonnes’, English Ministry website, 4 July.

· National Food and Strategic Reserves Administration (China) 2024, ‘China purchases over 400 mln tonnes of grain in 2023’, GOV.cn, 9 January. Available at: https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/statistics/202401/09/content_WS659d1020c6d0868f4e8e2e46.html

· Pakistan: 2022 Floods Response Plan, 2022. United Nations / Government of Pakistan, UN Digital Library.

· Shigemitsu, M. & Gray, E., 2021. ‘Building the resilience of Japan’s agricultural sector to typhoons and heavy rain’, OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, No. 159. Paris: OECD Publishing.

· UNDP & GCF, 2023. Enhancing Climate Resilience in Thailand through Effective Water Management and Sustainable Agriculture (E WMSA): Project Factsheet. UNDP, Bangkok.

· United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2025. ‘Rice Bank revives hope in flood hit hill tracts, Bangladesh’, UNDP, 19 June.

· World Bank, 2022. ‘Bangladesh: World Bank supports food security and higher incomes of farmers vulnerable to climate change’, World Bank press release, 15 March.

Features

Can we forecast weather precisely?

Weather forecasts are useful. People attentively listen to them but complain that they go wrong or are not taken seriously. Forecasts today are more probabilistically reliable than decades ago. The advancement of atmospheric science, satellite imaging, radar maps and instantly updated databases has improved the art of predicting weather.

Yet can we predict weather patterns precisely? A branch of mathematics known as chaos theory says that weather can never be foretold with certainty.

The classical mechanics of Issac Newton governing the motion of all forms of matter, solid, liquid or gaseous, is a deterministic theory. If the initial conditions are known, the behaviour of the system at later instants of time can be precisely predicted. Based on this theory, occurrences of solar eclipses a century later have been predicted to an accuracy of minutes and seconds.

The thinking that the mechanical behaviour of systems in nature could always be accurately predicted based on their state at a previous instant of time was shaken by the work of the genius French Mathematician Henri Poincare (1864- 1902).

Eclipses are predicted with pinpoint accuracy based on analysis of a two-body system (Earth- Moon) governed by Newton’s laws. Poincare found that the equivalent problem of three astronomical bodies cannot be solved exactly – sometimes even the slightest variation of an initial condition yields a drastically different solution.

A profound conclusion was that the behaviour of physical systems governed by deterministic laws does not always allow practically meaningful predictions because even a minute unaccountable change of parameters leads to completely different results.

Until recent times, physicists overlooked Poincare’s work and continued to believe that the determinism of the laws of classical physics would allow them to analyse complex problems and derive future happenings, provided necessary computations are facilitated. When computers became available, the meteorologists conducted simulations aiming for accurate weather forecasting. The American mathematician Edward Lorenz, who turned into a reputed meteorologist, carried out such studies in the early 1960s, arrived at an unexpected result. His equations describing atmospheric dynamics demonstrated a strange behaviour. He found that even a minute change (even one part in a million) in initial parameters leads to a completely different weather pattern in the atmosphere. Lorenz announced his finding saying, A flap of a butterfly wing in one corner of the world could cause a cyclone in a far distant location weeks later! Lorenz’s work opened the way for the development branch of mathematics referred to as chaos theory – an expansion of the idea first disclosed by Henri Poincare.

We understand the dynamics of a cyclone as a giant whirlpool in the atmosphere, how it evolves and the conditions favourable for their origination. They are created as unpredictable thermodynamically favourable relaxation of instabilities in the atmosphere. The fundamental limitations dictated by chaos theory forbid accurate forecasting of the time and point of its appearance and the intensity. Once a cyclone forms, it can be tracked and the path of movement can be grossly ascertained by frequent observations. However, absolutely certain predictions are impossible.

A peculiarity of weather is that the chaotic nature of atmospheric dynamics does not permit ‘long – term’ forecasting with a high degree of certainty. The ‘long-term’ in this context, depending on situation, could be hours, days or weeks. Nonetheless, weather forecasts are invaluable for preparedness and avoiding unlikely, unfortunate events that might befall. A massive reaction to every unlikely event envisaged is also not warranted. Such an attitude leads to social chaos. The society far more complex than weather is heavily susceptible to chaotic phenomena.

by Prof. Kirthi Tennakone (ktenna@yahoo.co.uk)

Features

When the Waters Rise: Floods, Fear and the ancient survivors of Sri Lanka

The water came quietly at first, a steady rise along the riverbanks, familiar to communities who have lived beside Sri Lanka’s great waterways for generations. But within hours, these same rivers had swollen into raging, unpredictable forces. The Kelani Ganga overflowed. The Nilwala broke its margins. The Bentara, Kalu, and Mahaweli formed churning, chocolate-brown channels cutting through thousands of homes.

When the floods finally began to recede, villagers emerged to assess the damage, only to be confronted by another challenge: crocodiles. From Panadura’s back lanes to the suburbs of Colombo, and from the lagoons around Kalutara to the paddy fields of the dry zone, reports poured in of crocodiles resting on bunds, climbing over fences, or drifting silently into garden wells.

For many, these encounters were terrifying. But to Sri Lanka’s top herpetologists, the message was clear: this is what happens when climate extremes collide with shrinking habitats.

“Crocodiles are not invading us … we are invading floodplains”

Sri Lanka’s foremost crocodile expert, Dr. Anslem de Silva, Regional Chairman for South Asia and Iran of the IUCN/SSC Crocodile Specialist Group, has been studying crocodiles for over half a century. His warning is blunt.

“When rivers turn into violent torrents, crocodiles simply seek safety,” he says. “They avoid fast-moving water the same way humans do. During floods, they climb onto land or move into calm backwaters. People must understand this behaviour is natural, not aggressive.”

In the past week alone, Saltwater crocodiles have been sighted entering the Wellawatte Canal, drifting into the Panadura estuary, and appearing unexpectedly along Bolgoda Lake.

“Saltwater crocodiles often get washed out to sea during big floods,” Dr. de Silva explains. “Once the current weakens, they re-enter through the nearest lagoon or canal system. With rapid urbanisation along these waterways, these interactions are now far more visible.”

- An adult Salt Water Crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) (Photo -Madura de Silva)

- Adult Mugger (Crocodylus plaustris) Photo -Laxhman Nadaraja

- A Warning sign board

- A Mugger holding a a large Russell ’s viper (Photo- R. M. Gunasinghe)

- Anslem de Silva

- Suranjan Karunarathna

This clash between wildlife instinct and human expansion forms the backdrop of a crisis now unfolding across the island.

A conflict centuries old—now reshaped by climate change

Sri Lanka’s relationship with crocodiles is older than most of its kingdoms. The Cūḷavaṃsa describes armies halted by “flesh-eating crocodiles.” Ancient medical texts explain crocodile bite treatments. Fishermen and farmers around the Nilwala, Walawe, Maduganga, Batticaloa Lagoon, and Kalu Ganga have long accepted kimbula as part of their environment.

But the modern conflict has intensified dramatically.

A comprehensive countrywide survey by Dr. de Silva recorded 150 human–crocodile attacks, with 50 fatal, between 2008 and 2010. Over 52 percent occurred when people were bathing, and 83 percent of victims were men engaged in routine activities—washing, fishing, or walking along shallow margins.

Researchers consistently emphasise: most attacks happen not because crocodiles are unpredictable, but because humans underestimate them.

Yet this year’s flooding has magnified risks in new ways.

“Floods change everything” — Dr. Nimal D. Rathnayake

Herpetologist Dr. Nimal Rathnayake says the recent deluge cannot be understood in isolation.

“Floodwaters temporarily expand the crocodile’s world,” he says. “Areas people consider safe—paddy boundaries, footpaths, canal edges, abandoned land—suddenly become waterways.”

Once the water retreats, displaced crocodiles may end up in surprising places.

“We’ve documented crocodiles stranded in garden wells, drainage channels, unused culverts and even construction pits. These are not animals trying to attack. They are animals trying to survive.”

According to him, the real crisis is not the crocodile—it is the loss of wetlands, the destruction of natural river buffers, and the pollution of river systems.

“When you fill a marsh, block a canal, or replace vegetation with concrete, you force wildlife into narrower corridors. During floods, these become conflict hotspots.”

Past research by the Crocodile Specialist Group shows that more than 300 crocodiles have been killed in retaliation or for meat over the past decade. Such killings spike after major floods, when fear and misunderstanding are highest.

“Not monsters—ecosystem engineers” — Suranjan Karunaratne

On social media, flood-displaced crocodiles often go viral as “rogue beasts.” But conservationist Suranjan Karunaratne, also of the IUCN/SSC Crocodile Specialist Group, says such narratives are misleading.

“Crocodiles are apex predators shaped by millions of years of evolution,” he says. “They are shy, intelligent animals. The problem is predictable human behaviour.”

In countless attack investigations, Karunaratne and colleagues found a repeated pattern: the Three Sames—the same place, the same time, the same activity.

“People use the same bathing spot every single day. Crocodiles watch, learn, and plan. They hunt with extraordinary patience. When an attack occurs, it’s rarely random. It is the culmination of observation.”

He stresses that crocodiles are indispensable to healthy wetlands. They: control destructive catfish populations, recycle nutrients, clean carcasses and diseased fish, maintain biodiversity, create drought refuges through burrows used by amphibians and reptiles.

“Removing crocodiles destroys an entire chain of ecological services. They are not expendable.”

Karunaratne notes that after the civil conflict, Mugger populations in the north rebounded—proof that crocodiles recover when given space, solitude, and habitat.

Floods expose a neglected truth: CEEs save lives—if maintained In high-risk communities, Crocodile Exclusion Enclosures (CEEs) are often the only physical barrier between people and crocodiles. Built along riverbanks or tanks, these enclosures allow families to bathe, wash, and collect water safely.

Yet Dr. de Silva recounts a tragic incident along the Nilwala River where a girl was killed inside a poorly maintained enclosure. A rusted iron panel had created a hole just large enough for a crocodile to enter.

“CEEs are a life-saving intervention,” he says. “But they must be maintained. A neglected enclosure is worse than none at all.”

Despite their proven effectiveness, many CEEs remain abandoned, broken or unused.

Climate change is reshaping crocodile behaviour—and ours

Sri Lanka’s floods are no longer “cycles” as described in folklore. They are increasingly intense, unpredictable and climate-driven. The warming atmosphere delivers heavier rainfall in short bursts. Deforested hillsides and filled wetlands cannot absorb it.

Rivers swell rapidly and empty violently.

Crocodiles respond as they have always done: by moving to calmer water, by climbing onto land, by using drainage channels, by shifting between lagoons and canals, by following the shape of the water.

But human expansion has filled, blocked, or polluted these escape routes.

What once were crocodile flood refuges—marshes, mangroves, oxbow wetlands and abandoned river channels—are now housing schemes, fisheries, roads, and dumpsites.

Garbage, sand mining and invasive species worsen the crisis

The research contained in the uploaded reports paints a grim but accurate picture. Crocodiles are increasingly seen around garbage dumps, where invasive plants and waste accumulate. Polluted water attracts fish, which in turn draw crocodiles.

Excessive sand mining in river mouths and salinity intrusion expose crocodile nesting habitats. In some areas, agricultural chemicals contaminate wetlands beyond their natural capacity to recover.

In Borupana Ela, a short study found 29 Saltwater crocodiles killed in fishing gear within just 37 days.

Such numbers suggest a structural crisis—not a series of accidents.

Unplanned translocations: a dangerous human mistake

For years, local authorities attempted to reduce conflict by capturing crocodiles and releasing them elsewhere. Experts say this was misguided.

“Most Saltwater crocodiles have homing instincts,” explains Karunaratne. “Australian studies show many return to their original site—even if released dozens of kilometres away.”

Over the past decade, at least 26 Saltwater crocodiles have been released into inland freshwater bodies—home to the Mugger crocodile. This disrupts natural distribution, increases competition, and creates new conflict zones.

Living with crocodiles: a national strategy long overdue

All three experts—Dr. de Silva, Dr. Rathnayake and Karunaratne—agree that Sri Lanka urgently needs a coordinated, national-level mitigation plan.

* Protect natural buffers

Replant mangroves, restore riverine forests, enforce river margin laws.

* Maintain CEEs

They must be inspected, repaired and used regularly.

* Public education

Villagers should learn crocodile behaviour just as they learn about monsoons and tides.

* End harmful translocations

Let crocodiles remain in their natural ranges.

* Improve waste management

Dumps attract crocodiles and invasive species.

* Incentivise community monitoring

Trained local volunteers can track sightings and alert authorities early.

* Integrate crocodile safety into disaster management

Flood briefings should include alerts on reptile movement.

“The floods will come again. Our response must change.”

As the island cleans up and rebuilds, the deeper lesson lies beneath the brown floodwaters. Crocodiles are not new to Sri Lanka—but the conditions we are creating are.

Rivers once buffered by mangroves now rush through concrete channels. Tanks once supporting Mugger populations are choked with invasive plants. Wetlands once absorbing floodwaters are now levelled for construction.

Crocodiles move because the water moves. And the water moves differently today.

Dr. Rathnayake puts it simply:”We cannot treat every flooded crocodile as a threat to be eliminated. These animals are displaced, stressed, and trying to survive.”

Dr. de Silva adds:”Saving humans and saving crocodiles are not competing goals. Both depend on understanding behaviour—ours and theirs.”

And in a closing reflection, Suranjan Karunaratne says:”Crocodiles have survived 250 million years, outliving dinosaurs. Whether they survive the next 50 years in Sri Lanka depends entirely on us.”

For now, as the waters recede and the scars of the floods remain, Sri Lanka faces a choice: coexist with the ancient guardians of its waterways, or push them into extinction through fear, misunderstanding and neglect.

By Ifham Nizam

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoWeather disasters: Sri Lanka flooded by policy blunders, weak enforcement and environmental crime – Climate Expert

-

News4 days ago

Lunuwila tragedy not caused by those videoing Bell 212: SLAF

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoLevel III landslide early warning continue to be in force in the districts of Kandy, Kegalle, Kurunegala and Matale

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoLevel III landslide early warnings issued to the districts of Badulla, Kandy, Kegalle, Kurunegala, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoDitwah: An unusual cyclone

-

Latest News6 days ago

Latest News6 days agoUpdated Payment Instructions for Disaster Relief Contributions

-

News21 hours ago

News21 hours agoA 6th Year Accolade: The Eternal Opulence of My Fair Lady

-

Latest News6 days ago

Latest News6 days agoLandslide Early Warnings issued to the Districts of Badulla, Colombo, Gampaha, Kalutara, Kandy, Kegalle, Kurunegala, Matale, Moneragala, Nuwara Eliya and Ratnapura