Opinion

On first reading Sir Edwin Arnold’s THE LIGHT OF ASIA – II

by Rohana R. Wasala

Edwin Arnold’s purpose in composing the epic The Light of Asia, then, was to give readers an unbiased idea about the exalted personality of prince Siddhartha and the general substance of his teaching. But he was not addressing this task in a religious cultural vacuum. He had to take care not to step too hard on the religious toes of his contemporary Christian compatriots. Undaunted by that challenge, Arnold opens his monumental epic with the line ‘The Scripture of the Saviour of the World’, which was startling in its being used to mean the Buddha and his doctrine. It must have sounded very distasteful to the Christian readers of the West, because it was not about Christ, but about the little known Indian sage the Buddha.

But then, it was a time of profound intellectual upheaval. The Age of Reason or the Enlightenment in Europe of well over one and a half centuries duration had preceded Charles Darwin’s revolutionary theory of biological evolution, that came to be known to the world through the publication of his epoch-making book ‘On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection’ (1859). By that time the Buddha was not totally unknown in the West. Ideas of ancient Eastern philosophers like Confucius of China and the Buddha of Bharat (India) as well as thoughts of their Western counterparts like Plato had influenced European thinkers of the time such as David Hume, Emmanuel Kant, and John Locke who figured in the enlightenment movement in Europe that came to be called the Age of Reason (1685-1815). The growing scientific ethos among the people undermined traditional religion and the fast spreading general scepticism regarding long held beliefs dealt a severe blow on theistic religion. Edwin Arnoldl’s senior contemporary Matthew Arnold (1822-1888), in his dramatic monologue ‘Dover Beach’ (1867), could only hear the receding ‘Sea of Faith,’

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar Retreating to the breath Of the night-wind, down to the vast edges drear And the naked shingles of the world.

The bleak barren desolate scene (with the ‘naked shingles of the world’: picture the wet pebbles on the indifferent beach constantly washed by the weeping waves) is a very depressing image of the uncertainty, the despair and the sadness that descended on a world that was losing the emotionally stabilising power of traditional religious faith. But it was also a time of bold inquiry and burgeoning hope. Edwin Arnold must have been emboldened by the existing zeitgeist of his time to shock his potential readers thus, only to offer them another more rational source of refuge to explore.

In terms of structure, The Light of Asia consists of eight cantos: Book the First, Book the Second, and so on up to Book the Eighth. The long epic poem employs the blank verse form, that is, lines of poetry without rhyme, that use a definite metre (a recurring pattern of rhythm) nevertheless. From the beginning to the end, the narrative is delivered in iambic pentameter lines (i.e., each line is made up of five metrical feet, each foot here being an iamb, that is, a foot consisting of a short syllable followed by a long syllable. Take any line from the poem, you can scan it into five iambic feet. But of course, occasionally, there are functional variations of the metre (as explained below). The opening line of Book the First (hence, of the whole poem) is ‘The Scripture of the Saviour of the World’, which can be scanned thus: The Scrip/ture of/the Sa/viour of/the World; the resulting stress pattern highlights the important words: Scripture, Saviour, World. The blank verse form more closely imitates the rhythm of natural speech than rhymed verse does, and, additionally, it makes for easy narrative continuity.

In Book the First, we are given the usual fictionalised narrative of how the Buddha-to-be descended from heaven to be born in the world of humans. Arnold recounts such details as Maya’s dream, its interpretation, and before all that, the ‘five sure signs of birth’ (which, though not specified in the poem, are equivalent to what we are familiar with as the Pas Maha Belum/the Great Fivefold Observation {kaalaya, deepaya, deshaya, kulaya, maata/time, land, state, caste, mother}) that preceded the Bodhisattva’s descent to the earth from ‘that sky’ (or the Tusita heaven according to Theravada Buddhist literature).

(Queen Maya)

Dreamed a strange dream; dreamed that a star from heaven –

Splendid, six-rayed, in colour rosy-pearl,

Whereof the token was an Elephant

Six-tusked, and white as milk of Kanadhuk –

Shot through the void; and shining into her,

Entered her womb upon the right…….

Thus was Siddhartha (the Bodhisattva/Buddha-to-be) conceived in his earthly mother’s womb. The birth takes place under a Palsa in the Palace-grounds in Kapilavastu (instead of under the shade between two Shala/Sal or cannonball trees on the way to Maya’s maternal home in Rajagriha/Rajgir, according to the story we know):

The conscious tree bent down its bows to make

A bower about Queen Maya’s Majesty;

And Earth put forth a thousand sudden flowers

To spread a couch……………

The narration of these miraculous occurrences which were claimed to have accompanied the birth of Siddhartha (‘All-Prospering’) did not spoil my enjoyment of the story, which was already known to me with similarly fantastic details, despite my then growing scepticism towards religion. People of different faiths usually adopt a healthy ‘suspension of disbelief’ when confronted with such fanciful accounts of events connected with the lives of religious figures that they adore, mostly because they are rational enough to read them as literature (a fact that Arnold himself was aware of and wanted his readers to understand as well).

The Queen mother dies seven days after the prince’s birth because she was ‘grown too sacred for more woe – And life is woe…………’

When old enough to learn all that a prince should learn, Siddhartha is entrusted to the wisest teacher available: Vishvamitra. But struck by the extraordinary precocity of his ‘softly-mannered, modest, deferent, tender-hearted…..’ royal charge, the old teacher

Prostrated before the boy; “For thou”, he cried,

Art Teacher of thy teachers – thou, not I,

“Art Guru. Oh I worship thee, sweet Prince!

The young prince also excelled in physical feats that formed a part of his training. He was a bold horseman and a skillful chariot driver. But he was so kindhearted that

Yet in mid-play the boy would oft-times pause,

Letting the deer pass free; would oft-times yield

His half-won race because his labouring steeds

Fetched painful breath; ……………………

One day while in play, Siddhartha’s cousin Devadatta shot a swan with an arrow and the injured bird fell to the ground. Siddhartha picked it up, removed the dart, and applied a poultice of soothing herbs on the wound. Though Devadatta wanted to have the bird that he had shot down, Siddhartha refused to give it back. An unknown priest suddenly appeared to mediate between the two cousins, and handed the bird to Siddhartha, saying that ‘the cherisher of life deserved the living bird, and not its slayer’. When the father king looked for the mysterious priest to reward him, he was gone:

And someone saw a hooded snake glide forth, –

The gods come oft-times thus! So our Lord Buddh

Began his works of mercy………………

It is in Book the Second that Arnold is seen giving full play to whatever he imbibed from his literary-aesthetic interaction with the Gita Govinda of Jayadeva, which Arnold seems to have used as a model for his own poetic masterpiece. The absolute devotion to the Buddha that Arnold expresses as an imaginary Buddhist votary in the capitalised last lines of the poem quoted in the epigraph to this essay indicates that his discovery of Buddhism was indeed a life changing experience.

While continuing my own narrative here, I consider this point an appropriate place to say something again about the form of the epic poem we are having a glance at. Now, too rigid an adherence to a set metrical foot is boringly mechanical at times (See the second paragraph above). Poets avoid this by varying it according to the context (as Shakespeare did in his plays). For example, from Book the Second we have

‘But they/ who watched/ the Prince/ at prize/-giving

Saw and/ heard all/ and told/ the care/ful King’

Here, the first line is a perfect iambic pentameter line. In the second line, however, the first two feet are trochees, not iambs; in a trochee, in contrast to an iamb, the stress or accent falls on the first syllable: Saw and/heard all/…. The context in the poem is where some courtiers, who have been attending on prince Siddhartha during a festival of royal beauties arranged by his father the ‘careful’ (full of care, i.e., worried, anxious) king Suddhodana on the advice of his wisemen to distract his eighteen year old young son from a premature otherworldliness that they had observed in his demeanour, are reporting to the king a sudden brightening of the prince’s mood on seeing the beautiful princess Yashodhara. What the watchful guards saw and heard passing between the two (Siddhartha and Yashodhara) gladdened them: they had instantly fallen in love with each other.

Whereas every one of the other maidens who came to receive gifts from the prince that day, even the fairest one among them,

….stood like a sacred antelope to touch

The gracious hand, then fled to join her mates

Trembling at favour, so divine he seemed,

So high and saint-like and above her world,

Yashodhara alone ‘Of heavenly mould’

Gazed full – folding her palms across her breasts –

On the boy’s gaze, her stately neck unbent.

“Is there a gift for me?” she asked, and smiled.

“The gifts are gone”, the Prince replied “yes take

This for amends, dear sister, of whose grace

Our happy city boasts”, therewith he loosed

The emerald necklet from his throat, and clasped

Its green beads round her dark and silk-soft waist;

And their eyes mixed, and from the look sprang love.

Those who stood nearest (the guards, no doubt) saw ‘the princely boy – Start, as the radiant girl approached….’ and they heard the sweet exchanges between the two instant lovers.The brief break in the metre in the verse line that records this highlights their (the guards’) joy and excitement at being finally able to bear the long awaited news of their happy finding to the fond father, the king they serve with so much love and loyalty.

This is a climactic moment of the whole scene (where the prince, set to choose his bride/his future queen consort, has just been rescued from his accustomed otherworldly melancholia). The king’s stratagem seems to be working. He wants his son to be a Chakravartin (lit. Turner of the Disc, a universal monarch) who will rule the world, not a holy man of wondrous wisdom. (As described in Book the First, these were the two alternative destinies that the dream-readers predicted for the baby conceived that night by Queen Maya. Ultimately, though,as we know, the king’s ambition for his son was not fulfilled. Siddhartha became Buddha instead of a Chackravartin.)

Long after Siddhartha attained Buddhahood, he is asked “why thus his heart – Took fire at first glance of the Sakya girl”, and he recalls an earlier life long gone by as

A hunter’s son, playing with forest girls

By Yamun’s springs, where Nandadevi stands,

Sate umpire while they raced beneath the firs

……………………………………………..

One with fir-apples; but who ran the last

Came first for him, and unto her the boy

Gave a tame fawn and his heart’s love beside.

This is just like a scene from Jayadeva’s Gita Govinda. Krishna/Govinda plays with Radha in a forest glade on the banks of the very same Yamuna. It is one of the swooning love scenes between the resplendent Blue God Krishna (in the form of Govinda) and the radiantly fair human cowherdess Radha during their heavenly trysts that Jayadeva enacts for us in his poem. While giving his account of the Siddhartha Yashodhara romance, Arnold is trying to infuse his poem with a touch of the divine magic of Jayadeva’s poetry.

Father Suddhodana creates for his son ‘….. a pleasant prison-house – Where love was gaoler and delights its bars’. The poet beautifully paints how the prince gradually grows tired of those delights. Around the end of Book the Fourth, Siddhartha has decided to renounce everything and embark on his lonely search for the Truth as a mendicant recluse. Channa, his charioteer, asks him:

Wilt thou ride hence and let the rich world slip

Out of thy grasp, to hold a beggar’s bowl?

Wilt thou go forth into the friendless waste

That has this Paradise of pleasures here?

The Prince made answer, “Unto this I came,

And not for thrones: the kingdom that I crave

Is more than many realms – and all things pass

To change and death………

The rest of the poem actualizes the ascetic Gautama’s painful exploration and his blissful ultimate discovery. Book the Seventh and Book the Eighth outline the doctrines of the Buddha as Edwin Arnold conceived of them in his essentially limited understanding of the Dhamma, which consisted of ‘the fruits of considerable study’ though. (Concluded)

Opinion

Capt. Dinham Suhood flies West

A few days ago, we heard the sad news of the passing on of Capt. Dinham Suhood. Born in 1929, he was the last surviving Air Ceylon Captain from the ‘old guard’.

He studied at St Joseph’s College, Colombo 10. He had his flying training in 1949 in Sydney, Australia and then joined Air Ceylon in late 1957. There he flew the DC3 (Dakota), HS748 (Avro), Nord 262 and the HS 121 (Trident).

I remember how he lent his large collection of ‘Airfix’ plastic aircraft models built to scale at S. Thomas’ College, exhibitions. That really inspired us schoolboys.

In 1971 he flew for a Singaporean Millionaire, a BAC One-Eleven and then later joined Air Siam where he flew Boeing B707 and the B747 before retiring and migrating to Australia in 1975.

Some of my captains had flown with him as First Officers. He was reputed to have been a true professional and always helpful to his colleagues.

He was an accomplished pianist and good dancer.

He passed on a few days short of his 97th birthday, after a brief illness.

May his soul rest in peace!

To fly west my friend is a test we must all take for a final check

Capt. Gihan A Fernando

RCyAF/ SLAF, Air Ceylon, Air Lanka, Singapore Airlines, SriLankan Airlines

Opinion

Global warming here to stay

The cause of global warming, they claim, is due to ever increasing levels of CO2. This is a by-product of burning fossil fuels like oil and gas, and of course coal. Environmentalists and other ‘green’ activists are worried about rising world atmospheric levels of CO2. Now they want to stop the whole world from burning fossil fuels, especially people who use cars powered by petrol and diesel oil, because burning petrol and oil are a major source of CO2 pollution. They are bringing forward the fateful day when oil and gas are scarce and can no longer be found and we have no choice but to travel by electricity-driven cars – or go by foot. They say we must save energy now, by walking and save the planet’s atmosphere.

THE DEMON COAL

But it is coal, above all, that is hated most by the ‘green’ lobby. It is coal that is first on their list for targeting above all the other fossil fuels. The eminently logical reason is that coal is the dirtiest polluter of all. In addition to adding CO2 to the atmosphere, it pollutes the air we breathe with fine particles of ash and poisonous chemicals which also make us ill. And some claim that coal-fired power stations produce more harmful radiation than an atomic reactor.

STOP THE COAL!

Halting the use of coal for generating electricity is a priority for them. It is an action high on the Green party list.

However, no-one talks of what we can use to fill the energy gap left by coal. Some experts publicly claim that unfortunately, energy from wind or solar panels, will not be enough and cannot satisfy our demand for instant power at all times of the day or night at a reasonable price.

THE ALTERNATIVES

It seems to be a taboo to talk about energy from nuclear power, but this is misguided. Going nuclear offers tried and tested alternatives to coal. The West has got generating energy from uranium down to a fine art, but it does involve some potentially dangerous problems, which are overcome by powerful engineering designs which then must be operated safely. But an additional factor when using URANIUM is that it produces long term radioactive waste. Relocating and storage of this waste is expensive and is a big problem.

Russia in November 2020, very kindly offered to help us with this continuous generating problem by offering standard Uranium modules for generating power. They offered to handle all aspects of the fuel cycle and its disposal. In hindsight this would have been an unbelievable bargain. It can be assumed that we could have also used Russian expertise in solving the power distribution flows throughout the grid.

THORIUM

But thankfully we are blessed with a second nuclear choice – that of the mildly radioactive THORIUM, a much cheaper and safer solution to our energy needs.

News last month (January 2026) told us of how China has built a container ship that can run on Thorium for ten years without refuelling. They must have solved the corrosion problem of the main fluoride mixing container walls. China has rare earths and can use AI computers to solve their metallurgical problems – fast!

Nevertheless, Russia can equally offer Sri Lanka Thorium- powered generating stations. Here the benefits are even more obviously evident. Thorium can be a quite cheap source of energy using locally mined material plus, so importantly, the radioactive waste remains dangerous for only a few hundred years, unlike uranium waste.

Because they are relatively small, only the size of a semi-detached house, such thorium generating stations can be located near the point of use, reducing the need for UNSIGHTLY towers and power grid distribution lines.

The design and supply of standard Thorium reactor machines may be more expensive but can be obtained from Russia itself, or China – our friends in our time of need.

Priyantha Hettige

Opinion

Will computers ever be intelligent?

The Island has recently published various articles on AI, and they are thought-provoking. This article is based on a paper I presented at a London University seminar, 22 years ago.

Will computers ever be intelligent? This question is controversial and crucial and, above all, difficult to answer. As a scientist and student of philosophy, how am I going to answer this question is a problem. In my opinion this cannot be purely a philosophical question. It involves science, especially the new branch of science called “The Artificial Intelligence”. I shall endeavour to answer this question cautiously.

Philosophers do not collect empirical evidence unlike scientists. They only use their own minds and try to figure out the way the world is. Empirical scientists collect data, repeat and predict the behaviour of matter and analyse them.

We can see that the question—”Will computers ever be intelligent?”—comes under the branch of philosophy known as Philosophy of Mind. Although philosophy of mind is a broad area, I am concentrating here mainly on the question of consciousness. Without consciousness there is no intelligence. While they often coincide in humans and animals, they can exist independently, especially in AI, which can be highly intelligent without being conscious.

AI and philosophers

It appears that Artificial Intelligence holds a special attraction for philosophers. I am not surprised about this as Al involves using computers to solve problems that seem to require human reasoning. Apart from solving complicated mathematical problems it can understand natural language. Computers do not “understand” human language in the human sense of comprehension; rather, they use Natural Language Processing (NLP) and machine learning to analyse patterns in data. Artificial Intelligence experts claim certain programmes can have the possibility of not only thinking like humans but also understanding concepts and becoming conscious.

The study of the possible intelligence of logical machines makes a wonderful test case for the debate between mind and brain. This debate has been going on for the last two and a half centuries. If material things, made up entirely of logical processes, can do exactly what the brain can, the question is whether the mind is material or immaterial.

Although the common belief is that philosophers think for the sake of thinking, it is not necessarily so. Early part of the 20th century brought about advances in logic and analytical philosophy in Britain. It was a philosopher (Ludwig Wittgenstein) who invented the truth table. This was a simple analytic tool useful in his early work. But this was absolutely essential to the conceptual basis of early computer science. Computer science and brain science have developed together and that is why the challenge of the thinking machine is so important for the philosophy of mind. My argument so far has been to justify how and why AI is important to philosophers and vice versa.

Looking at computers now, we can see that the more sophisticated the computer, the more it is able to emulate rather than stimulate our thought processes. Every time the neuroscientists discover the workings of the brain, they try to mimic brain activity with machines.

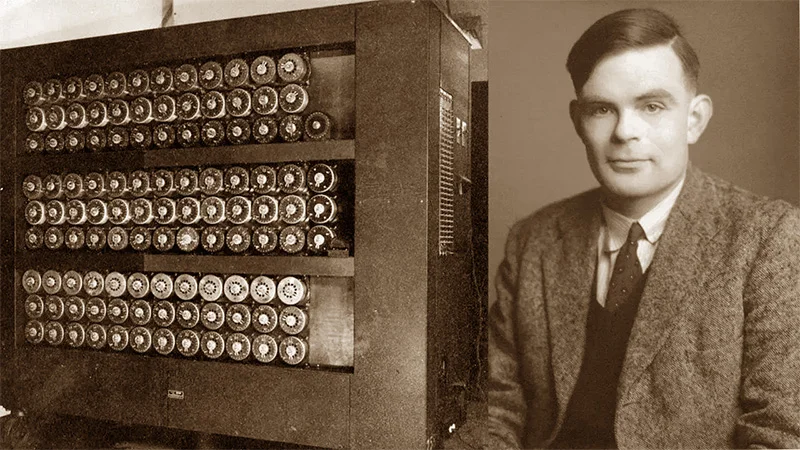

How can one tell if a computer is intelligent? We can ask it some questions or set a test and study its response and satisfy ourselves that there is some form of intelligence inside this box. Let us look at the famous Alan Turing Test. Imagine a person sitting at a terminal (A) typing questions. This terminal is connected to two other machines, (B) and (C). At terminal (B) sits another person (B) typing responses to the questions from person (A). (C) is not a human being, but a computer programmed to respond to the questions. If person (A) cannot tell the difference between person (B) and computer(C), then we can deduce that computer is as intelligent as person (B). Critics of this test think that there is nothing brilliant about it. As this is a pragmatic exercise and one need not have to define intelligence here. This must have amused the scientists and the philosophers in the early days of the computers. Nowadays, computers can do much more sophisticated work.

Chinese Room experiment

The other famous experiment is John Sealer’s Chinese room experiment. *He uses this experiment to debunk the idea that computers could be intelligent. For Searle, the mind and the brain are the same. But he warns us that we should not get carried away with the emulative success of the machines as mind contains an irreducible subjective quality. He claims that consciousness is a biological process. It is found in humans as well as in certain animals. It is interesting to note that he believes that the mind is entirely contained in the brain. And the empirical discovery of neural processes cannot be applied to outside the brain. He discards mind-body dualism and thinks that we cannot build a brain outside the body. More commonly, we believe the mind is totally in the brain, and all firing together and between, and what we call ‘thought’ comes from their multifarious collaboration.

Patricia and Paul Churchland are keen on neuroscientific methods rather than conventional psychology. They argue that the brain is really a processing machine in action. It is an amazing organ with a delicately organic structure. It is an example of a computer from the future and that at present we can only dream of approaching its processing speed. I think this is not something to be surprised about. The speed of the computer doubles every year and a half and in the distant future there will be machines computing faster than human beings. Further, the Churchlands’, strongly believe that through science one day we will replicate the human brain. To argue against this, I am putting forward the following true story.

I remember watching an Open University (London) education programme some years ago. A team of professors did an experiment on pavement hawkers in Bogota, Colombia. They were fruit sellers. The team bought a large number of miscellaneous items from these street vendors. This was repeated on a number of occasions. Within a few seconds, these vendors did mental calculations and came out with the amounts to be paid and the change was handed over equally fast. It was a success and repeatable and predictable. The team then took the sample population into a classroom situation and taught them basic arithmetic skills. After a few months of training they were given simple sums to do on selling fruit. Every one of them failed. These people had the brain structure that of ordinary human beings. They were skilled at their own jobs. But they could not be programmed to learn a set of rules. This poses the question whether we can create a perfect machine that will learn all the human transferable skills.

Computers and human brains excel at different tasks. For instance, a computer can remember things for an infinite amount of time. This is true as long as we don’t delete the computer files. Also, solving equations can be done in milliseconds. In my own experience when I was an undergraduate, I solved partial differential equations and it took me hours and a lot of paper. The present-day students have marvellous computer programmes for this. Let alone a mere student of mathematics, even a mathematical genius couldn’t rival computers in the above tasks. When it comes to languages, we can utter sentences of a completely foreign language after hearing it for the first time. Accents and slang can be decoded in our minds. Such algorithms, which we take for granted, will be very difficult for a computer.

I always maintain that there is more to intelligence than just being brilliant at quick thinking. A balanced human being to my mind is an intelligent person. An eccentric professor of Quantum Mechanics without feelings for life or people, cannot be considered an intelligent person. To people who may disagree with me, I shall give the benefit of the doubt and say most of the peoples’ intelligence is departmentalised. Intelligence is a total process.

Other limitations to AI

There are other limitations to artificial intelligence. The problems that existing computer programmes can handle are well-defined. There is a clear-cut way to decide whether a proposed solution is indeed the right one. In an algebraic equation, for example, the computer can check whether the variables and constants balance on both sides. But in contrast, many of the problems people face are ill-defined. As of yet, computer programmes do not define their own problems. It is not clear that computers will ever be able to do so in the way people do. Another crucial difference between humans and computers concerns “common sense”. An understanding of what is relevant and what is not. We possess it and computers don’t. The enormous amount of knowledge and experience about the world and its relevance to various problems computers are unlikely to have.

In this essay, I have attempted to discuss the merits and limitations of artificial intelligence, and by extension, computers. The evolution of the human brain has occurred over millennia, and creating a machine that truly matches human intelligence and is balanced in terms of emotions may be impossible or could take centuries

*The Chinese Room experiment, proposed by philosopher John Searle, challenges the idea that computers can truly “understand” language. Imagine a person locked in a room who does not know Chinese. They receive Chinese symbols through a slot and use an instruction manual to match them with other symbols to produce correct replies. To outsiders, it appears the person understands Chinese, but in reality, they are only following rules. Searle argues that similarly, a computer may process language convincingly without genuine understanding or consciousness.

by Sampath Anson Fernando

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoMy experience in turning around the Merchant Bank of Sri Lanka (MBSL) – Episode 3

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoRemotely conducted Business Forum in Paris attracts reputed French companies

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoFour runs, a thousand dreams: How a small-town school bowled its way into the record books

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoComBank and Hayleys Mobility redefine sustainable mobility with flexible leasing solutions

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoAutodoc 360 relocates to reinforce commitment to premium auto care

-

Midweek Review3 days ago

Midweek Review3 days agoA question of national pride

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoWill computers ever be intelligent?

-

Midweek Review3 days ago

Midweek Review3 days agoTheatre and Anthropocentrism in the age of Climate Emergency