Features

Old Kalutara and Lorenz

By Avishka Mario Senewiratne

“There is an old Sinhalese saying that ‘happy is the man who is born at Matara and bred at Kalutara.’ Lorenz must have been happy that he was born at Matara and had his well-known holiday home at Kalutara.”- E. H. Van der Waal

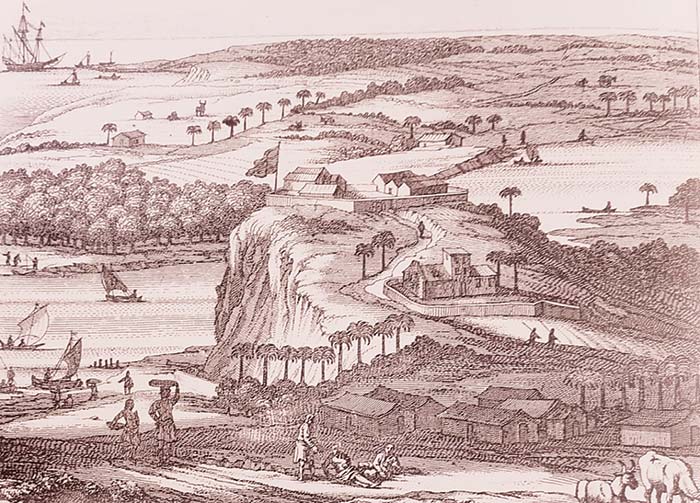

Kalutara, 28 miles south of Colombo is perhaps one of the most underrated regions in Sri Lanka. One of my first memories of this palm-fringed coastal city from an aerial view was the thousands of coconut trees, the fabulous Kalu Ganga flowing to the ocean, and the mighty Kalutara Bodhiya as well as old Churches built by European missionaries. The Portuguese realized the strategic and military importance of Kalutara (Caltura as it was known then) and built a fort between 1620 and 1623 demolishing the ancient Gangathilaka Vihare. (see Illustrations and Views of Dutch Ceylon, p. 205).

This was an assignment taken by General Jorge d’Alburquerque. The land of the fort was a hillock on the southern bank of Kalu Ganga. After the Portuguese were ousted, the Dutch under General Gerard Hulft captured Kalutara. The Dutch took a greater interest in this Fort and its environs. Christopher Schweitzer, a German working for the VOC, stated in 1682 that he was one of the 30 soldiers involved in adding ramparts to Kalutara in 1677. In 1672, the Dutch predikant Baldeus noted that “… the Fortress of Caltura situated in a most lovely locality lies near the mouth of a large and broad river close by the sea. This defence is strongly built with double earthen walls…”

Governor Ryckloff Van Goens Sr. took Kalutara more seriously and was assigned to build a road from Kalutara to Colombo, “along which eight men could march abreast, taking with them field guns.” In 1744, Dutch traveler J. W. Heydt commented on the great progress of cinnamon cultivation in Kalutara. In 1796, the Kalutara fort was ceded by British troops under General Stuart.

After many years of disuse, the Kalutara Fort premises were used as the residence of the Government Agent of Kalutara in 1915. In the early 1960s, this land was taken over by the Kalutara Bodhi Trust and a dagoba was erected after nearly 400 years. Many British individuals who served and lived in Ceylon during the 18th century wrote a manifold of books initially targeting the English audience, who was known to be curious about the new British colony.

Captain Robert Percival writes a great detail about Kalutara in his An Account of an Island in 1803. He reveals that the old fort was dilapidated by that time. He makes a special note of the hunting of wild animals, especially fox in Kalutara. Percival writes: “From Pantura (Panadura) to Caltura, a distance of ten miles, the whole country may be considered as one delightful grove; and the road has entirely the appearance of a broad walk through a shady garden… the grateful refreshment such a road affords to a traveller in this sultry climate, can only be conceived by those who have passed from Columbo to Caltura”. (pp. 125-126)

Rev. James Cordiner comments on Kalutara in his 1807 Description of Ceylon: “Here is a small fortification raised upon a mount, commanding the banks of a beautiful river… a neat village, chiefly in one street, built of stone on thatched roofs, inhabited by native Cingalese, and black descendants of native Portuguese. The climate is cool, the place is rural and the situation pleasant.” (p. 174)

Major Jonathan Forbes writes in his Eleven Years in Ceylon, on Kalutara on his way to Colombo, “There is considerable variety of ground and scenery.” (1840, part II, p. 167)

Sir James Emerson Tennent wrote: “Caltura has always been regarded as one of the sanitaria of Ceylon, and as it faces the sea breeze from the south-west, the freshness of its position, combined with the beauty and grandeur of the surrounding scenery, rendered it the favourite resort of the Dutch, and afterwards of the British… from the great extent of the coconut groves which surround it, Caltura is one of the principal places for the distillation of Arrack.” (Tennent, part II, p. 659)

One of the first prominent Europeans to build a country residence in Kalutara was John Rodney, the Colonial Secretary.

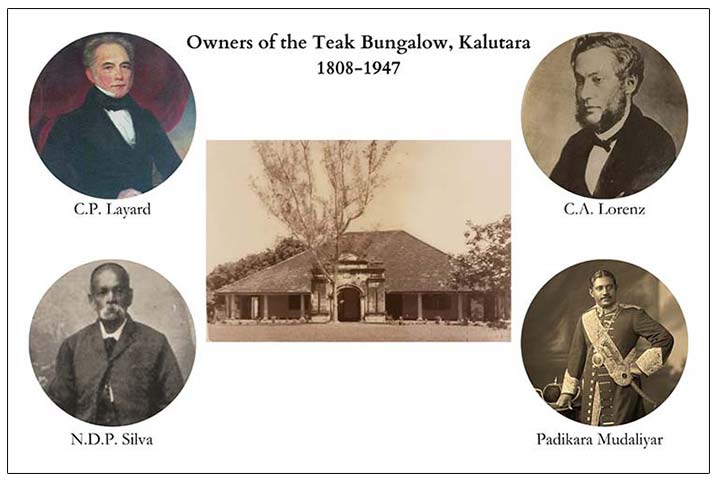

Teak Bungalow

Extending up to nine acres and resting on the banks of Kalu Ganga, this opulent property was originally called ‘Mount Layard’. It belonged to Charles Edward Layard (1787-1852), C.C.S., father of Sir C. P. Layard, Government Agent of the Western Province. Layard married a Dutch Burgher lady called Barbara Bridgetina Mooyart. They bore 26 children of which 21 survived infancy. The Layards occupied this house between the years 1808 and 1814, when Charles Layard was the Collector for Kalutara (See Toussaint, J. R., (1935), Annals of the Ceylon Civil Service, p. 59). While residing in Kalutara, Layard and James Anthony Mooyart attempted to cultivate sugar cane. However, the experiment was futile.

J. W. Bennet comments on this in his monumental 1843 tome Ceylon and its Capabilities as follows: “These gentlemen introduced the culture of the sugar cane, but upon too extensive a scale for a first experiment; and, owing to the quantity of iron with which the soil there is almost everywhere impregnated, were unsuccessful.” (p. 34) When Rev. Reginald Heber, the Anglican Bishop of Calcutta visited Ceylon in 1825 he lodged in this house for a few days. Heber wrote the following in his journal:

“Culture, where in a very pretty bungalow belonging to Mr. Layard, commanding a beautiful view of the river and sea we breakfasted’

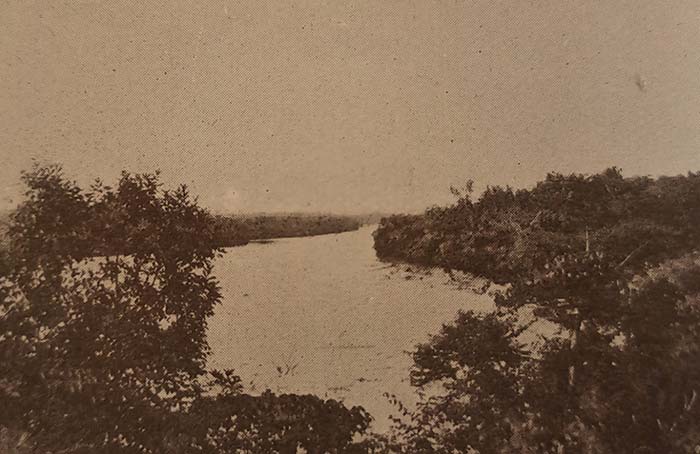

Commenting on the view of Kalu Ganga from Mount Layard, J. W. Bennet wrote the following in Ceylon and its Capabilities:

“The view from Mount Layard, the country residence of Charles Edward Layard, Esq., on the left bank of the river, is beautiful; but one scarcely knows which of the two reaches of the river to admire most:—the old fort, an island, and the open sea over the sandy ridge, make the view down the river the finest, but for the Indian impression given by the areka trees and coco-nut topes;—but the mellow richness of the scenery up the river towards Gal-Pata, would, to a Cockney, appear a Richmond Hill style of beauty, and of course be in his eyes the most interesting.” (p. 375)

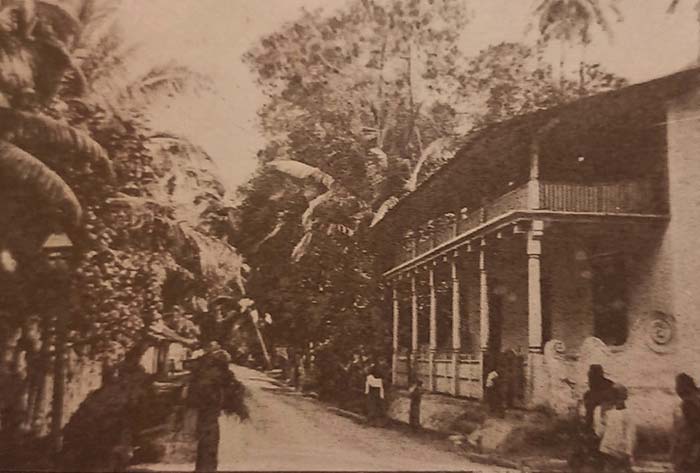

- An old Dutch House in Kalutara by H.W. Cave

- A view of Kalu Ganga from the Teak Bungalow. Photographed by H.W. Cave, 1908

A few years after Layard died in 1852, Lorenz who was by then well-off owing to a sound legal practice purchased “Mount Layard” and re-named it “Teak Bungalow”. This was obviously due to the large number of teak trees on the property. Lorenz bought the adjoining properties bearing coconut trees and paddy fields along with this compound. He named his nephew Edwin Poulier as Superintendent. Poulier was known to have done a good job with the estate. Annually for about six weeks during the Easter recess, Lorenz lodged in Teak Bungalow.

Here he dispensed hospitality and entertained his many friends. Among those friends who visited Lorenz frequently at the Teak Bungalow were two Van Cuylenbergs. One of them, a medical doctor was the father of Sir Hector Van Cuylenberg. Proctor F. S. Thomasz of Kalutara was another frequent visitor. Apart from hosting them, Lorenz would often invite them to shooting parties. In the August 1933 issue of The Ceylon Causerie, E. H. Van der Wall records an interesting statement by an old resident who recalled Lorenz quite well:

“Lorenz frequently visited ‘Teak Bungalow’ for weekends, travelling by stages in his charabanc with two gray horses, and accompanied by a multitude of nephews and nieces. Almost invariably on the day of arrival a lady, who was previously notified, supplied a string-hopper breakfast. This breakfast was served in the large dining room and the guests were seated on mats used for drying paddy. Lorenz also sat on a mat at the head of the party. No knives, spoons or forks were used at the repast, the use of fingers being de rigueur.”

The walls of the Teak Bungalow were adorned by sketches of various people by Lorenz himself. These included District Judge Christoffels de Saram and Dr. Van Cuylenberg. Another interesting story centered around Lorenz is that on one occasion he appeared successfully for a native doctor called Haltota Veda. As a result, the native doctor who was grateful to Lorenz, cultivated his field by the Teak Bungalow for free. On a later occasion, Haltota Veda was made an Arachchi on the recommendation of Lorenz to the Government Agent C. P. Layard. While being lodged here, Lorenz completed his third volume of the Law Reports (Lorenz was the pioneer of writing law reports in Sri Lanka). While suffering various ailments in the latter part of his life, Lorenz came to the Teak Bungalow on several occasions in the belief of recovery from the far-famed climate. Foxes were plentiful around the Teak Bungalow compound and they would often destroy crops and fruit-bearing trees. Observing this Lorenz sketched the following poem:

One Emma and two Alices

Leaving pleasures and palaces,

Are observing Edward Poulier

Shooting at a Vowlia

Teak Bungalow was put on sale after the untimely death of Lorenz in 1872. However, until a buyer was found, this house was rented as the official residence of the Assistant Government Agent of Kalutara. When an attempt by the Government to acquire the Teak Bungalow failed, the Appeal Court held that the property was not required for a public purpose (See The Ceylon Causerie, August 1933, p. 12). Sometime later the business tycoon nicknamed ‘Plumbago King’, N. D. P. Silva purchased the Teak Bungalow and used it as his country house (Twentieth Century Impressions of Ceylon, pp. 591-594). N. D. P. Silva’s son was the Padikara Mudaliyar N. D. Arthur Silva Wijesinghe, who built the Richmond Castle in Kalutara. The reception for his wedding took place at the Teak Bungalow in 1910. This esteemed and popular abode of some of Ceylon’s most celebrated personalities does not exist anymore. In the 1930s the premises of the former Teak Bungalow housed an Excise Warehouse.

Features

Recruiting academics to state universities – beset by archaic selection processes?

Time has, by and large, stood still in the business of academic staff recruitment to state universities. Qualifications have proliferated and evolved to be more interdisciplinary, but our selection processes and evaluation criteria are unchanged since at least the late 1990s. But before I delve into the problems, I will describe the existing processes and schemes of recruitment. The discussion is limited to UGC-governed state universities (and does not include recruitment to medical and engineering sectors) though the problems may be relevant to other higher education institutions (HEIs).

How recruitment happens currently in SL state universities

Academic ranks in Sri Lankan state universities can be divided into three tiers (subdivisions are not discussed).

* Lecturer (Probationary)

– recruited with a four-year undergraduate degree. A tiny step higher is the Lecturer (Unconfirmed), recruited with a postgraduate degree but no teaching experience.

* A Senior Lecturer can be recruited with certain postgraduate qualifications and some number of years of teaching and research.

* Above this is the professor (of four types), which can be left out of this discussion since only one of those (Chair Professor) is by application.

State universities cannot hire permanent academic staff as and when they wish. Prior to advertising a vacancy, approval to recruit is obtained through a mind-numbing and time-consuming process (months!) ending at the Department of Management Services. The call for applications must list all ranks up to Senior Lecturer. All eligible candidates for Probationary to Senior Lecturer are interviewed, e.g., if a Department wants someone with a doctoral degree, they must still advertise for and interview candidates for all ranks, not only candidates with a doctoral degree. In the evaluation criteria, the first degree is more important than the doctoral degree (more on this strange phenomenon later). All of this is only possible when universities are not under a ‘hiring freeze’, which governments declare regularly and generally lasts several years.

Problem type 1

– Archaic processes and evaluation criteria

Twenty-five years ago, as a probationary lecturer with a first degree, I was a typical hire. We would be recruited, work some years and obtain postgraduate degrees (ideally using the privilege of paid study leave to attend a reputed university in the first world). State universities are primarily undergraduate teaching spaces, and when doctoral degrees were scarce, hiring probationary lecturers may have been a practical solution. The path to a higher degree was through the academic job. Now, due to availability of candidates with postgraduate qualifications and the problems of retaining academics who find foreign postgraduate opportunities, preference for candidates applying with a postgraduate qualification is growing. The evaluation scheme, however, prioritises the first degree over the candidate’s postgraduate education. Were I to apply to a Faculty of Education, despite a PhD on language teaching and research in education, I may not even be interviewed since my undergraduate degree is not in education. The ‘first degree first’ phenomenon shows that universities essentially ignore the intellectual development of a person beyond their early twenties. It also ignores the breadth of disciplines and their overlap with other fields.

This can be helped (not solved) by a simple fix, which can also reduce brain drain: give precedence to the doctoral degree in the required field, regardless of the candidate’s first degree, effected by a UGC circular. The suggestion is not fool-proof. It is a first step, and offered with the understanding that any selection process, however well the evaluation criteria are articulated, will be beset by multiple issues, including that of bias. Like other Sri Lankan institutions, universities, too, have tribal tendencies, surfacing in the form of a preference for one’s own alumni. Nevertheless, there are other problems that are, arguably, more pressing as I discuss next. In relation to the evaluation criteria, a problem is the narrow interpretation of any regulation, e.g., deciding the degree’s suitability based on the title rather than considering courses in the transcript. Despite rhetoric promoting internationalising and inter-disciplinarity, decision-making administrative and academic bodies have very literal expectations of candidates’ qualifications, e.g., a candidate with knowledge of digital literacy should show this through the title of the degree!

Problem type 2 – The mess of badly regulated higher education

A direct consequence of the contemporary expansion of higher education is a large number of applicants with myriad qualifications. The diversity of degree programmes cited makes the responsibility of selecting a suitable candidate for the job a challenging but very important one. After all, the job is for life – it is very difficult to fire a permanent employer in the state sector.

Widely varying undergraduate degree programmes.

At present, Sri Lankan undergraduates bring qualifications (at times more than one) from multiple types of higher education institutions: a degree from a UGC-affiliated state university, a state university external to the UGC, a state institution that is not a university, a foreign university, or a private HEI aka ‘private university’. It could be a degree received by attending on-site, in Sri Lanka or abroad. It could be from a private HEI’s affiliated foreign university or an external degree from a state university or an online only degree from a private HEI that is ‘UGC-approved’ or ‘Ministry of Education approved’, i.e., never studied in a university setting. Needless to say, the diversity (and their differences in quality) are dizzying. Unfortunately, under the evaluation scheme all degrees ‘recognised’ by the UGC are assigned the same marks. The same goes for the candidates’ merits or distinctions, first classes, etc., regardless of how difficult or easy the degree programme may be and even when capabilities, exposure, input, etc are obviously different.

Similar issues are faced when we consider postgraduate qualifications, though to a lesser degree. In my discipline(s), at least, a postgraduate degree obtained on-site from a first-world university is preferable to one from a local university (which usually have weekend or evening classes similar to part-time study) or online from a foreign university. Elitist this may be, but even the best local postgraduate degrees cannot provide the experience and intellectual growth gained by being in a university that gives you access to six million books and teaching and supervision by internationally-recognised scholars. Unfortunately, in the evaluation schemes for recruitment, the worst postgraduate qualification you know of will receive the same marks as one from NUS, Harvard or Leiden.

The problem is clear but what about a solution?

Recruitment to state universities needs to change to meet contemporary needs. We need evaluation criteria that allows us to get rid of the dross as well as a more sophisticated institutional understanding of using them. Recruitment is key if we want our institutions (and our country) to progress. I reiterate here the recommendations proposed in ‘Considerations for Higher Education Reform’ circulated previously by Kuppi Collective:

* Change bond regulations to be more just, in order to retain better qualified academics.

* Update the schemes of recruitment to reflect present-day realities of inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary training in order to recruit suitably qualified candidates.

* Ensure recruitment processes are made transparent by university administrations.

Kaushalya Perera is a senior lecturer at the University of Colombo.

(Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.)

Features

Talento … oozing with talent

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

Last week we had MISTER Band in our scene, and on 10th February, Yellow Beatz – both social media favourites.

Talento is a seven-piece band that plays all types of music, from the ‘60s to the modern tracks of today.

The band has reached many heights, since its inception in 2012, and has gained recognition as a leading wedding and dance band in the scene here.

The members that makeup the outfit have a solid musical background, which comes through years of hard work and dedication

Their portfolio of music contains a mix of both western and eastern songs and are carefully selected, they say, to match the requirements of the intended audience, occasion, or event.

Although the baila is a specialty, which is inherent to this group, that originates from Moratuwa, their repertoire is made up of a vast collection of love, classic, oldies and modern-day hits.

The musicians, who make up Talento, are:

Prabuddha Geetharuchi:

(Vocalist/ Frontman). He is an avid music enthusiast and was mentored by a lot of famous musicians, and trainers, since he was a child. Growing up with them influenced him to take on western songs, as well as other music styles. A Peterite, he is the main man behind the band Talento and is a versatile singer/entertainer who never fails to get the crowd going.

Geilee Fonseka (Vocals):

A dynamic and charismatic vocalist whose vibrant stage presence, and powerful voice, bring a fresh spark to every performance. Young, energetic, and musically refined, she is an artiste who effortlessly blends passion with precision – captivating audiences from the very first note. Blessed with an immense vocal range, Geilee is a truly versatile singer, confidently delivering Western and Eastern music across multiple languages and genres.

Chandana Perera (Drummer):

His expertise and exceptional skills have earned him recognition as one of the finest acoustic drummers in Sri Lanka. With over 40 tours under his belt, Chandana has demonstrated his dedication and passion for music, embodying the essential role of a drummer as the heartbeat of any band.

Harsha Soysa:

(Bassist/Vocalist). He a chorister of the western choir of St. Sebastian’s College, Moratuwa, who began his musical education under famous voice trainers, as well as bass guitar trainers in Sri Lanka. He has also performed at events overseas. He acts as the second singer of the band

Udara Jayakody:

(Keyboardist). He is also a qualified pianist, adding technical flavour to Talento’s music. His singing and harmonising skills are an extra asset to the band. From his childhood he has been a part of a number of orchestras as a pianist. He has also previously performed with several famous western bands.

Aruna Madushanka:

(Saxophonist). His proficiciency in playing various instruments, including the saxophone, soprano saxophone, and western flute, showcases his versatility as a musician, and his musical repertoire is further enhanced by his remarkable singing ability.

Prashan Pramuditha:

(Lead guitar). He has the ability to play different styles, both oriental and western music, and he also creates unique tones and patterns with the guitar..

Features

Special milestone for JJ Twins

The JJ Twins, the Sri Lankan musical duo, performing in the Maldives, and known for blending R&B, Hip Hop, and Sri Lankan rhythms, thereby creating a unique sound, have come out with a brand-new single ‘Me Mawathe.’

In fact, it’s a very special milestone for the twin brothers, Julian and Jason Prins, as ‘Me Mawathe’ is their first ever Sinhala song!

‘Me Mawathe’ showcases a fresh new sound, while staying true to the signature harmony and emotion that their fans love.

This heartfelt track captures the beauty of love, journey, and connection, brought to life through powerful vocals and captivating melodies.

It marks an exciting new chapter for the JJ Twins as they expand their musical journey and connect with audiences in a whole new way.

Their recent album, ‘CONCLUDED,’ explores themes of love, heartbreak, and healing, and include hits like ‘Can’t Get You Off My Mind’ and ‘You Left Me Here to Die’ which showcase their emotional intensity.

Readers could stay connected and follow JJ Twins on social media for exclusive updates, behind-the-scenes moments, and upcoming releases:

Instagram: http://instagram.com/jjtwinsofficial

TikTok: http://tiktok.com/@jjtwinsmusic

Facebook: http://facebook.com/jjtwinssingers

YouTube: http://youtube.com/jjtwins

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoAn innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoRatmalana Airport: The Truth, The Whole Truth, And Nothing But The Truth

-

Features6 days ago

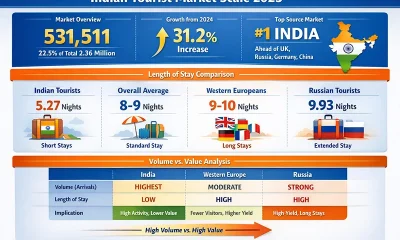

Features6 days agoBuilding on Sand: The Indian market trap

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoFuture must be won

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoDialog partners with Xiaomi to introduce Redmi Note 15 5G Series in Sri Lanka

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoIRCSL transforms Sri Lanka’s insurance industry with first-ever Centralized Insurance Data Repository

-

Opinion1 day ago

Opinion1 day agoSri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans