Features

Myth of unemployable arts graduates

(This is a response by a group of Sri Lankan university teachers to the audit report Propensity to tend education under the Arts stream and the unemployment of Arts Graduates.

Recently, the Committee on Public Accounts discussed a report prepared by the audit office, entitled “Propensity to tend education under the Arts stream and the unemployment of Arts Graduates.” The somewhat awkwardly titled report attempts to connect graduate unemployment to Arts Education at secondary and tertiary levels. The report is useful in that it locates some of the problems of tertiary education in a failing secondary educational system. The recommendations made in the report are also, for the most part, salutary. However, the assumptions that inform the body of the report, the material that it uses to come to conclusion regarding arts education, and the manner in which it is committed to undervaluing Arts Education, merits comment, especially in a policy environment where Arts Education is under attack. Arguably the manner in which it conceptualizes the role of education in society is limited and reflects all current policy making on the subject. We provide this analysis, therefore, to broaden the conversation driving the policy discourse regarding higher education in the country and to move it away from its current unhelpful preoccupation with employability. We argue in this response that to formulate policy on a narrowly defined understanding of “employability” is insufficient and does not adequately encompass areas in Humanities and Social Science higher education that require strengthening through reform and support. Currently, policies driven by “employability” are, in fact, negatively impacting Humanities and Social Science programmes within the university system.

The report usefully highlights a fundamental problem in our education system – the failing secondary schools – as impacting Arts Education in general. Using a range of data, the report is able to demonstrate how the system is fundamentally unequal and makes clear that the policy of free education is failing the most marginalized members and communities in our society. The report highlights the fact that many schools do not have resources to provide Advanced Level science education. And states also that many parents are not able to support Advanced Level science education due to their inability to provide funds for extra classes. Therefore, many who are economically marginalized are unable to pursue education in STEM subjects. The report also demonstrates that the provinces, where poverty is greatest, have the largest percentages of Arts students entering university.

In terms of the numbers taking up subjects for the Advanced Level examination, the largest percentage opt for the Arts stream. The report claims that students choose Arts subjects because they are “easy” and students can enter university quickly (through their first shy). The numbers of students that choose the Arts stream for the A-Levels have ranged between 40-50 percent in 2017/2018. Other than in the Western Province, where the numbers are slightly lower, (20-35%), all other provinces had close to 50% of all A-Level students follow Arts subjects (Audit report, pp14-21). Documenting how students who are compelled to attend under-resourced secondary schools have few choices with regards to their education, the report recommends that the education system address the inequality of access and provide all secondary school students the choice of pursing either a STEM focused education or one in Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences. We support this recommendation of the report. The report, however, fails to connect how the inequality that prevails in the school system and the inability to guarantee a good basic education for all, in turn limits the impact that higher education can make when no intervention specifically addresses this problem. The report then suggests that the graduates that the current system of Arts Education produces are unemployable and emphasizes the need to reduce the numbers that opt for the Arts stream. Such a reduction of numbers was planned through the introduction of the technology stream. However, the technology stream itself has its own problems, is insufficiently resourced and has not been a success in reducing the numbers choosing the Arts stream. Unfortunately, there is no recognition in the report that most students are being taught within a severely under-funded and under-resourced Arts stream and that strengthening Arts education itself would be an option that would result in Arts graduates with a higher quality Arts education.

The report is inadequately informed of what Arts education encompasses and the current state of tertiary Arts education in the country.

What is Arts Education?

While acknowledging the need for the Arts to enrich society, the report suggests that as a “developing country”, we have to emphasize economic growth and suggests that we cannot afford to spend resources (that could be spent on Science Technology Engineering Mathematics (STEM) education) on Arts education. Making reference to “literary men, actors, musicians and cinematographers and artists” as necessary for a society, the report states that we, as a developing country, must have a greater emphasis on growing the economy. It is unfortunate that the report’s authors consider the country to be undeserving of investment in the Arts and culture until economic development is achieved and also dissociates the Arts from engagement with economic activity. The lack of greater government support for the Arts is probably a reflection of this sensibility. Unfortunately, such shortsighted positions inform the report and much of education policy today. A vibrant society where the Arts and culture can thrive should be an aspiration that we should cultivate and share.

Arts Faculties also provide degrees in the social sciences, such as sociology, psychology, economics and geography, and in applied or “professional” fields such as education, archeology, and library sciences, as well as humanities subjects such as history, philosophy and literature, and modern and classical languages. Nowhere does the report name the wide variety of subjects that are categorized under Arts education or recognize the importance of such subjects. Other than pointing out in one instance that developed countries use their system of education to create “skilled persons”, while we in Sri Lanka create “academic persons,” the report only recognizes Arts subjects insofar as they are not Science Mathematics or Technology subjects. The skills and perspectives provided by the Humanities and Social Sciences (Arts subjects) are essential to a holistic understanding of any social problem, such as poverty or education, or even any “technical” problem, such as water scarcity. The ability to understand the philosophical and ideological bases of such problems, and identify the social, cultural, and human consequences of proposed solutions, is provided by the skillset cultivated by an Arts education. In fact, this is the very reason that multidisciplinary perspectives are frequently called upon for policy research. It is important then that we recognize the contribution that a good quality Arts education can offer to society. We as a country are suffering today from a lack of attention to the perspectives that social science and humanities education can provide. This is also why those with little or no exposure to the above fields feel qualified to drive policy in various sectors that have substantial social consequences. This situation does not bode well for our future.

As indicated in the quotation above where the Sri Lankan system is accused of producing “academic persons” as opposed to skilled individuals, the report assumes that academically-oriented programmes are somehow antithetical to programmes that provide employment-oriented “skills.” Such a perspective mischaracterizes both the nature of academic engagement and the essence of job-oriented training. A strong academic programme that focuses on critical thought, substantive engagement with course material, independent learning, good writing, presentation and debate skills, will enable graduates to think independently, express themselves and work towards creating meaningful change in whatever surrounding they find themselves in, including their jobs. An effective programme of this nature would simultaneously result in the development of English skills, “soft skills”, and IT skills as part of the curriculum. The World Bank loan funded AHEAD programme, currently being implemented across the university system, has integrated elements of such a perspective and Bank loan supported initiatives are no longer insisting—as they did in earlier cycles– that we carry out stand-alone programmes to cultivate English, IT and “soft skills.”

The contention of the report as stated earlier is that Arts education is the subject area into which the largest numbers of the country’s students flock, and is also the repository of the country’s poorest students. The report then sweepingly suggests that arts programmes draw “weak” students and are themselves “weak” and are of little societal value. This seems to be the preferred policy position with regards to Arts Education. The report notes that the Technology Stream was introduced with the goal of reducing the number of Arts students to less than 25 percent and increasing the number of students pursuing Maths, Science and Technology. The report establishes, however, that the demand for Arts subjects among the student population has increased despite government efforts to decrease the number. The report’s lack of interest in understanding what positive elements of Arts education might be attracting the large student numbers (other than perhaps the ability to become a lawyer) and what elements of Arts education are worth supporting and developing, is quite telling of its general devaluing of Arts education.

The report provides little insight into the content of Arts programmes that are offered by the Sri Lankan university system and its assessment of the efficacy of the programmes is limited to employment numbers provided by the UGC Tracer Study of 2016/17. The report also states that no statistical information is available on unemployed graduates although insights from the Unemployed Graduates Union were obtained. Its critique of the programmes is based on two criteria – the number of programme revisions that have been reported and the introduction of new programmes of study. Outside of the above criteria, the study does not recognize the many differences among Arts degree programmes. For one, not all Arts programmes are the same across the country’s university system. There are internal and external degree programs, three-year general arts degree programmes following different subject combinations and Study Stream degree programmes that offer specialization within a three-year period, and four-year honours degree programmes involving a research component. While the subject areas covered by Arts programmes are also diverse, the content of programmes across the many universities differ as well. Thus, Arts students demonstrate a wide and disparate range of abilities and skills. Addressing Arts Education as a non-disaggregated whole is unhelpful when analyzing the skills and capabilities of Arts graduates and numbers that refer only to programme review and the introduction of new programmes does not adequately capture the status of those programmes. Disaggregating between Arts programmes is essential in order to recognize and develop the new and evolving programmes and provide support for the areas that require reforms.

Arts Faculties currently cater to a large number of students and relative to other faculties, their student body is more diverse and are likely to have differing and greater challenges and require greater support in transitioning to university education. Their student to staff ratios are larger, they tend to offer a large number of degree programmes that are delivered in different language media, and their per student funding is lesser than for other degree programmes. This creates a number of unique difficulties for arts faculties. These problems require systematic investigation in order for universities to provide the type of enriching education that an arts graduate requires.

These concerns that plague arts education cause difficulties in giving the arts graduate the type of education that they require and deserve. In the Commission’s report, these complex problems are not adequately presented or discussed.

Arts Education and Employment.

We recognize that some students who follow an arts education may have difficulties in finding work. As the report points out these difficulties stem partly from the immense social and economic disparities that influence student educational pathways and subsequent employment paths. The report suggests a number of solutions through which employment related problems that Arts students face may be addressed. These solutions proposed in the report require aligning educational paths with employment paths, through coordination among educational and employment providing institutions and greater funding for secondary and tertiary education. We pose, however three issues that the report has failed to address in making this case:

1. Framing recommendations with a rigorous analysis of the labour/job markets and their forecasts. The report neglects to include analyses of the job market or forecasts of the labour force. It does not address national policy to attract and create jobs, which are consistent with national trends in human capital. In short, the report does not link jobs and employment to broader policies to create good quality jobs that are secure and safe to all employees (see for instance, ILO, 2004). As a result, how the report construes where graduates will be placed once they graduate is unclear. Such an analysis should now be sensitive to changes caused by the Covid 19 pandemic, which likely hit youth and women particularly hard (ILO, 2020). Problems of the employment of arts graduates are especially salient to youth and women.

2. Justifying the linkages between employment and university education. The report rests on the assumption that students who follow a university education will become an “economic good”, meaning that their education will be transformed into some tangible, national, and tradable good. Yet the nature of this good is unclear, particularly considering that the labour market is in flux (see Blenkinsopp, 2011). For instance, with the rise in automation, jobs themselves are transforming in all sectors (see Oliver, 2015, Rothwell & Rothwell, 2016). These trends are likely to drastically reduce the number of jobs available and change how work is carried out. Skillsets, particularly those that are narrowly defined and context-specific, which are relevant and desired today, may have no importance in years to come. Thus, an analysis of jobs specific skills training, required of young people for employment in the future, should begin with an analysis of job markets of the future. Whether providing these skills should be the primary role of universities and whether the country has the jobs required for such trained individuals are also questions that will need to be addressed.

3. The report also rests on the assumption that learning activities that specifically target narrowly defined soft skills and skills in ICT and English language will result in the economic good mentioned in #2. This assumption has no basis. For instance, a strong humanities or social science education can provide invaluable skills in thinking critically (see Fahim & Masouleh, 2012) that are very much relevant to jobs. Within the study of job-related competencies, conceptual and thinking skills that are adaptable across job contexts and Reinforce a desire and ability to learn for oneself are particularly important (Snow & Snell, 1993). Cultivating these types of foundational skills require a curriculum that is built on a gradual and sustained process of developing them (see Fahim & Masouleh, 2012) rather than one-off courses that teach students a narrow skill set.

Education, Work and Economic Development

For most university graduates, employment means to be employed in the government sector. When graduates report unemployment, they do not necessarily mean they are not engaged in other income-generating activities or a private sector job. (One of the reasons for unemployment noted in the report is to be waiting for a government job.) Defining a “job” as a government job alone may be understood as part of a cultivated culture of patronage and entitlement. Such a position also draws from a realization that the working conditions, job security, and benefits of a government position far outweigh those in the private sector, regardless of claims to creativity, job satisfaction, higher pay, etc. Additionally, most private sector jobs are only available in and around urban areas. The report recognizes many of these issues and recommends raising awareness on the benefits of private sector jobs among undergraduates and urges the government to address the working conditions in the private sector.

The report points out that the majority of unemployed Arts graduates are women, but does not explore the gendered reasons as to why university educated women may be unemployed or opt out of employment. The Labour Demand Survey of 2017 provides insights on this matter. According to the Survey results, employers expressed negative attitudes towards hiring women owing to their “family commitments,” “security concerns”, and “maternity leave.” Employers’ reluctance to accommodate women’s unpaid care responsibilities and fear of sexual harassment and violence point to yet another societal malaise that is not reducible to a factor of university education alone. Not only are women overburdened with care work and at risk of violence in society, employers neither recognize nor provide support to women to work despite these challenges. Recent discussions on the unpaid care economy and women’s unaccounted labour at home are relevant here.

Many women opt out of formal employment or engage in informal work to accommodate the demands of care work in the home. Additionally, workplace sexual harassment and risk of the same when traveling home late after work are factors that contribute to women’s low labour force participation. These issues must be taken into account to arrive at a complete picture of graduate unemployment.

The audit report highlights the fact that we, as a “developing country”, must concentrate on economic advancement. However, there is no acknowledgement that one of the factors that have directly impacted the Sri Lankan economy and continues to do so has been ethno religious conflict. Over 30 years of war, and after the end of the war increasing numbers of organized violent attacks against Muslims, and the Easter Sunday bombings carried out by Muslims channelling the rhetoric of global Islamic terrorism to respond to local problems have destroyed lives and livelihoods and decimated the Sri Lankan economy. There is no analysis of how universities could provide a space to imagine alternatives to conflict and hostility and how such alternatives can be nurtured.

Unfortunately, education institutions have so far served to produce, reproduce and sustain Sinhala-Buddhist hegemonic narratives and to glorify ‘Sinhala-Buddhist’ culture at the expense of the stories and the culture of the country’s minority communities. These political efforts to divide and pit communities against each other encounter little or no ideological resistance. It is ironic that policy makers choose to see no connection between the country’s long history of ethnoreligious conflict and the system of education. Instead of playing a vital role in building trust in the post-war context among our communities, the education system has served to perpetuate structural violence along class, gender, ethnic and other lines. It is time that policy makers and political leaders discuss the manner in which education will help nurture a polity that can imagine collective engagement that is not overdetermined by conflict.

No doubt education has to cater to the economic needs of society, but the world has come a long way since ‘development’ was reduced to the ‘economy’. Contemporary approaches to development are much broader with far-reaching goals and meanings beyond the economy. Education should be a vehicle for achieving larger social goals through the development of creative capabilities and peaceful co-existence, which could, in turn, facilitate realizing economic goals within a society that is not plagued by violence.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Addressing the problems that plague Arts education in Universities, will strengthen not only Arts education in the University system but education in general. By framing the problem more widely, we propose the following:

The Education System:

1. The salutary goals that were envisioned when a free education system was introduced to the country still remain relevant. The social transformation that education continues to promise to countless Sri Lankan citizens is currently under severe strain. Therefore it is important that the challenges to the free education system be recognized and addressed in a manner that strengthens its foundational principles of universality and equality of access.

2. Broaden the understanding of the problems of the education system. Employability—narrowly defined– should not be the only framework from which reform of education should be approached. Education as a democratic endeavor must be recognized and questions must be raised as to whether the education system succeeds in strengthening democracy.

3. Ensure that education at both the secondary and tertiary levels is designed to overturn ethno-religious tensions and prejudices related to class, caste gender, gender identity and sexual orientation.

4. Provide solutions to address the inequalities in access to secondary education options, and minimize disparities in resources, facilities, and teachers.

Arts Education:

5. Provide arts faculties with the option of having foundation courses that will better equip students to perform well in degree programmes.

6. Have a better understanding of the different Arts degree programmes in the country, conduct a holistic analysis of the problems facing arts education and provide support when needed and reform where needed.

7. Increase spending on Arts Education. Recognize the contribution that Humanities and Social Sciences can make to society and provide support for such programmes.

8. Recognize and support the unique environments of the Arts Faculties as arguably consisting of the most diverse student bodies and serving the largest number of under privileged students.

9. Resist the formulation of one- size-fits-all policies for the improvement of Humanities and Social Science Education.

Technology Stream:

10. Ensure that students are guided into such streams through provision of services at both secondary and tertiary levels.

11. Provide trained teachers for technology education, revisit curricula, and improve infrastructure facilities.

Employment and employment markets:

12. Look into the job requirement of the country and the policies in place for job creation.

13. Ensure laws are in place to provide the necessary support services for women to enter the labour force.

14. Provide greater state support for the Creative Arts (as a job creation strategy that will strengthen the economy).

15. Ensure that the benefits and work conditions in the private sector match those of the public sector and remain attractive to university graduates

Features

Anura-Modi Pact: The elephant in the room is the dragon

In a historic first for Sri Lanka, a “defence pact” was signed last week by President AKD with Prime Minister Modi of India, to the surprise of the people of Sri Lanka who had no inkling that such a thing was on the cards. It has justifiably given rise to agitated discussion in this country, not only due to the secrecy surrounding the contents of the “pact”, but also due to its sudden emergence. For a seriously consequential decision such as this, there had been zero discussion in the public domain, and the defence pact was practically sprung on the public during the two-day visit of the leader of the neighbouring giant, India.

In 2019, an Australian researcher at the Institute of National Security Studies Sri Lanka (INSSSL) Ms. Lucy Stronach, urged the use of Defence White Papers for “assessing necessity and analysing structures for Sri Lanka’s next strategic priority”.

Udeshika Jayasekara reports in the INSSL website the researcher’s submission that “The absence of a well-developed defence white paper could hinder Sri Lanka’s strategic response to a changing security environment…She stressed that a Sri Lankan defence white paper should present the Government’s position on defence policy, objectives and strategies, with specific mention to the security environment and threats, future defence directions, and military doctrine.”

Stronach explains that “All strategies that are made must be evidence-based in nature [rather than influenced for political or personal gain], and decisions should be made as cost-effectively as possible whilst adhering to core government objectives and policy.” (https://www.inss.lk/index.php?id=231)

A White Paper is not a secret document, but one that is made available to the public. For instance, the Australian Defence White Papers which consider its defence cooperation with India, are in the public domain. Such a White Paper on Sri Lanka-India Defence cooperation which goes beyond the existing arrangements for the first time in its history, formalising a defence pact, would have reassured the public and other global actors that all relevant issues had been considered before arriving at such a momentous decision with national security implications.

Soon after the Doklam stand-off between India and China in 2017, in a piece that I wrote titled “Between Dragons & Elephants: Sri Lanka’s Dangerous Quest For Cash From China & India”, I quoted the foreign editor of the Hindustan Times, Pramit Paul Chaudri who wrote that after the 2017 Doklam affair which took place outside “Indian soil or Indian claimed territory”, India and China were “more likely to run into each other in third countries”.

A Bhutani journalist reflected after this event with some relief that they have so far avoided “both the fire from the Dragon on our heads and also the Elephant’s tusks in our soft underbelly”. (https://www.colombotelegraph.com/index.php/between-dragons-elephants-sri-lankas-dangerous-quest-for-cash-from-china-india/)

Sri Lanka has several think tanks, Diplomatic and Defence institutes including a university (KDU), and a post-graduate institute at the National Defence College, that must surely track current global trends and their implications for Sri Lanka, its national security, economic security, sovereignty and territorial integrity. Were there adequate consultations on the most recent, critical step the government has just taken in the domain of defence?

Has Sri Lanka veered away from its traditional foreign policy position of balancing between India and China, successfully practiced by all regimes to-date, and moved under the AKD/NPP administration to throw in our lot with our giant neighbour without any public discussion, despite the complex historical relationship of incursions, wars, and interventions on sensitive ethnic issues?

INDIA-US Defence Cooperation

The India -Sri Lanka defence pact has been signed in the aftermath of greatly enhanced defence cooperation between the United States and India. Unlike the yet to be disclosed ‘pact’ signed by President AKD, the joint statement following the 13th February 2025 meeting between Prime Minister Modi and President Trump gave great details on their agreements, within the day.

Released on the same day that the leaders met in the Indian Ministry of External Affairs, the joint statement recognizes India as a “Major Defense Partner with Strategic Trade Authorization-1 (STA-1) authorisation and a key Quad partner, the U.S.” (https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/39066/India__US_Joint_Statement_February_13_2025)

The Joint statement states that “The leaders also called for opening negotiations this year for a Reciprocal Defense Procurement (RDP) agreement to better align their procurement systems and enable the reciprocal supply of defense goods and services. The leaders pledged to accelerate defense technology cooperation across space, air defense, missile, maritime and undersea technologies, with the U.S. announcing a review of its policy on releasing fifth generation fighters and undersea systems to India.”

It also says, “The leaders committed to break new ground to support and sustain the overseas deployments of the U.S. and Indian militaries in the Indo-Pacific, including enhanced logistics and intelligence sharing…with other exchanges and security cooperation engagements.” The increasing defence cooperation between India and the US has inevitably been seen as being part of the on-going attempts to contain China, by Chinese analysts.

Chunhao Lou of the China Institute of Contemporary International Relations writes that “Defence cooperation between the US and India has become increasingly focused on targeting China, creating real challenges for China’s national security.” He reveals that their joint military exercises, Yudh-Abyas 21 and 22, held after the Galvan Valley incident, took place not 100 kilometers from China’s Actual Line of Control, “clearly indicating a strategic focus against China”. (http://www.cicir.ac.cn/UpFiles/file/20241114/6386720528685461646420295.pdf, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

He asks if this move away from India’s traditional non-alignments policy means a move towards a US-India Alliance, but concludes that scholars are yet to agree on the “essence of the partnership” and that “sovereignty-transfer issues” involved in formal alliance will prevent India from going that far. However, he says that the agreements show “clear intentions against third parties…” which show “some characteristics of an alliance”, and therefore describes it as “more of a quasi-alliance”.

He discloses that India’s multilateral Malabar exercises have included anti-submarine warfare and that the US sent a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier to participate in the 2022 event. He mentions with concern India’s plans to become a hub for the maintenance and repair of “forward-deployed US Navy assets and other aircraft and vessels”. He also mentions the 2023 US proposal to India to be included in a NATO-plus arrangement, which had been publicly rejected by Foreign Minister Jaishankar. The report acknowledges that it is “impossible for India to compromise its sovereignty”.

Who, What, How?

The continuing lack of transparency with regard to the Anura-Modi defence pact are making people nervous about the government’s motivations. At first, it wasn’t clear if the Cabinet had given approval to it, nor who had participated in negotiating its contents.

Several days later following questions from the media as well as parliamentarians, the Secretary of Defence chose to confirm that it had in fact received Cabinet approval, placing accountability for it and its contents on the government. The contents are yet to be revealed to the public, as is the logic that necessitated such a step, moving beyond the defence cooperation arrangements already in place.

The people are justified in feeling a sense of dissonance for several reasons, not least among them the history of uncompromising opposition to any such arrangement with India, by the dominant partner in the governing coalition, the JVP. This fact more than any other, compels the citizens to seek to understand how the anxieties articulated at length and over decades by the JVP and its leader, now the powerful President of the country, has been resolved, and the factors that secured this leap of faith.

India’s Foreign Secretary Vikram Mishri explained at the Press Briefing on April 5th 2025 on PM Modi’s visit to Sri Lanka that the defence pact “proceeds from” the conversations between the two leaders starting in December 2024, when President AKD visited Delhi. He said that there was “really close convergence” of the “recognition of the completely interlinked nature of the national security of Sri Lanka and India…This is the background of the signature of the defense MOU between the two countries for the first time, and the MOU is in itself an umbrella framework document that will make existing defense cooperation initiatives more structured.” (https://www.hcicolombo.gov.in/section/speeches-and-interviews/transcript-of-special-briefing-by-mea-on-prime-minister-s-visit-to-sri-lanka-april-05-2025/)

Many in Sri Lanka would want to know contours of the “completely interlinked nature” of Sri Lanka’s national security with India’s, especially given the geopolitics of region, the ethnic dimension of the long war, and the divergent national interests of the two countries over time.

The President’s reading of our national interest led to some concern when he decided against attending the BRICS Plus summit, weeks after being elected to the Presidency, not even sending either his Prime Minister, or the Foreign Minister. The chief bureaucrat of the Foreign Ministry attended the Heads of State summit instead. The members of BRICS have been Sri Lanka’s traditional allies, and it would have been an opportunity for the new government to renew those relationships. The recent tariff shock experienced across the globe reflected negatively in major stock exchanges around the world including ours which stopped trading for 30 minutes, validates the urging of diversifying of our dependency and the balancing of major powers using non-alignment in its former and revised forms that Sri Lanka had privileged, over the last decades.

People have a right to be concerned, when a government makes an about-turn without explanation. They want to know that their interests and that of the country have been considered adequately, as well as the concerns of other global players, who are also big powers such as China, who have stood by them in times of difficulty.

They want to know that this government is capable of playing the role that a small island situated in an important strategic location, is called upon to play at this globally critical time, when the world order is in transition to something which is yet unclear. Analysts suggest that taking the long historical view, transitions invariably involve war, resistance to change, contestation and eventual emergence of a hegemonic power, but not before a period of violent transition. We need to know that our government can navigate this complexity intelligently, not ignorantly, taking the long view, and driven primarily by the national interest of Sri Lanka.

By Sanja de Silva Jayatilleka

Features

Sri Lanka’s Foreign Policy amid Geopolitical Transformations: 1990-2024 – Part III

Global Strategic Transformations

Since the 16th century, global power has largely been concentrated in the West, driven by European colonial expansion, industrialisation, and later, US dominance. However, in the 21st century, this balance is gradually, yet profoundly, shifting. This global power shift is evident in four key trends that have shaped the post-Cold War era: the relative decline of the United States, a renewed Cold War-style rivalry between China and the US, Asia’s resurgence, and the US policy shift—its pivot to Asia and the Indo-Pacific. Sri Lanka’s foreign policy must navigate these structural shifts, which carry significant implications for economic partnerships, security alliances, and geopolitical positioning.

Relative Decline of the United States

The relative economic and political decline of the United States, in the new millennium, marked a pivotal turning point in global power dynamics. The US leadership interpreted the end of the Cold War as an ideological victory for liberal democracy. The Cold War did not end through a violent military confrontation, but rather as a result of the voluntary dissolution of the Soviet Union. In the immediate aftermath, the United States emerged as the world’s sole superpower, the undisputed leader of the global order. However, over time, the US began to face mounting challenges from both internal and external factors. The 2008 financial crisis, the rise of Islamic fundamentalism, the protracted wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and increasing domestic political polarization all contributed to a decline in US global influence.

The decline of US power, as a global leader, is not sudden. As early as 1973, President Richard Nixon acknowledged that the post-war era in international relations had ended. He observed that the United States had shifted from a nuclear monopoly in the mid-1940s to nuclear superiority in the 1950s and, by the 1960s, to rough strategic parity with the Soviet Union. The Nixon-Kissinger leadership predicted that more complex multi-polar power relations were emerging, replacing the simple bi-polar alignments that characterised the post-World War II era. He also noted that the changing mood of the American people signalled the end of the postwar international order. At the beginning of the Cold War, the US public strongly supported a global leadership role. However, Nixon observed that “after almost three decades, our enthusiasm was waning and the results of our generosity were being questioned. Our policies need change, not only to match new realities in the world but also to meet a new mood in America” (Nixon, Shaping a Durable Peace, 1973: 3). Nixon’s observations on the shifting US global role became particularly relevant in the post-Cold War era, three decades later. The rise of nationalist and inward-looking policies, epitomised by President Donald Trump’s ‘Make America Great Again’ démarche, reflected a renewed skepticism toward US global commitments. His policies, along with his return to the political stage, underscored the tensions between America’s global leadership roles and growing concerns about its relative US economic and political decline.

The transformation of US policy in the Indian Ocean reflects the relative decline of American hegemony in the region. While the US initially relied on military dominance—anchored by Diego Garcia as a critical logistics hub—shifts in global power dynamics have forced a strategic recalibration. The growing influence of China, the rise of regional naval powers, like India, and increasing challenges to unilateral US military presence, have made it difficult to sustain the same level of dominance. As a result, US policy has evolved from a posture of overwhelming military superiority to a more nuanced, cooperative, and regionally integrated approach, signalling a shift in its ability to unilaterally dictate security dynamics in the Indian Ocean. The Operation Desert Shield and Operation Desert Storm (1991) successfully expelled Iraqi forces from Kuwait but entangled the US in prolonged Middle Eastern conflicts. Similarly, Operation Enduring Freedom (2001) swiftly removed the Taliban from power in Kabul, yet the economic and human costs of maintaining a long-term presence in Afghanistan underscored the limitations of US military interventions in the post-Cold War historical context.

China’s Rise and Evolving

‘New Cold War’

China has taken on an increasingly proactive role in global diplomacy and economics, solidifying its position as a 21st-century superpower. This growing leadership is evident in major initiatives, like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), both of which expand China’s influence on the world stage. The Economist noted that “China’s decision to fund a new multilateral bank rather than give more to existing ones reflects its exasperation with the glacial pace of global economic governance reform” (The Economist, 11 November 2014). Thus far, China’s ascent to global superpower status has been largely peaceful.

China’s influence is evident in its extensive investments in port infrastructure, maritime trade routes, and strategic partnerships under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The United States sees this growing presence as a direct challenge to its global dominance, particularly as China deepens its economic entrenchment and modernises its military. US officials worry that dual-use facilities, an expanding naval footprint, and greater regional influence could undermine power projection, disrupt open sea lanes, and weaken allied security. In response, the US has intensified alliances, expanded security cooperation, and bolstered its military presence to counteract what it perceives as an erosion of its global primacy. As a result, the intensifying rivalry between China and the United States appears to be shaping the global strategic landscape in the 21st century.

The current Sino-US rivalry differs from the US-Soviet Cold War in several key aspects. Unlike the Soviet Union, which primarily contested US dominance in military and strategic spheres, China’s challenge to US hegemony is largely economic. This competition intensified during the Trump administration, particularly through the US-China trade war. Given the deep interdependence of global economic activities, US tariffs on Chinese goods have had repercussions for both countries, affecting Americans as much as Chinese producers and consumers.

Indian Ocean small states, such as Sri Lanka, do not necessarily perceive Chinese economic initiatives through a power-political lens. Instead, they assess these initiatives based on their own economic interests and the benefits they offer. Consequently, the US strategy used to counter the Soviet threat during the Cold War is unlikely to be effective in addressing the current challenge posed by China.

China’s progress in the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) adds another dimension to US-China rivalry in trade and technology, digital geopolitics. In 2015, China initiated its ‘Made in China 2025’ plan, aimed at advancing high-tech manufacturing capabilities.The worldwide challenge of the dominance of US IT giants, including Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft by Chinese IT giants, such as Alibaba, Baidu, and Tencent of came forefront in digital geopolitics. The competition to develop 5G infrastructures, viewed by both powers as pivotal for enabling the next generation of digital application, has added a new dimension to their rivalry.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is another critical frontier in UU-China competition. In March 2016, Google advanced machine-learning technology by integrating algorithms and reinforcement learning to process big data and enhance predictive capabilities. A year later, in July 2017, President Xi Jinping unveiled China’s ‘New Generation AI Development Plan,’ aiming to position China as the global leader in AI by 2030. The plan underscores the strategic advantage of exclusive technological control, allowing a nation to establish dominance before rivals can catch up (Pecotic, 2019). As Sri Lanka embarks on acquiring Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI), it must navigate the intensifying digital geopolitical rivalry among global tech giants. Countries like Sri Lanka, which have only recently begun acquiring Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI), must navigate carefully in the face of digital geopolitical rivalry among global powers such as China, India, and the United States.

Resurgence of Asia and the Asian Century

Another crucial development that signifies the global shift of power is the resurgence of Asia, driven by the strategic rise of China and India, along with the sustained economic growth of other key Asian economies, often referred to as the ‘Asian Tigers.’ This transformation has led to the widespread characterisation of the 21st century as the ‘Asian Century.’ The region’s rapid economic expansion, technological advancements, and growing geopolitical influence have reshaped global power dynamics, positioning Asia at the heart of international affairs. In 2019, the World Economic Forum declared, “We’ve entered the Asian Century, and there is no turning back” (World Economic Forum, 2019). This assertion reflects Asia’s role as the primary driver of global economic growth, trade, and innovation. With China and India leading the way, alongside the economic resilience of nations like Japan, South Korea, and the ASEAN bloc, Asia is not merely rising—it is redefining the global order.

In the Asian Century, the Indian Ocean has emerged as a pivotal geopolitical arena where the global balance of power is increasingly contested and reshaped. As major economic and military powers vie for influence in this strategically vital region, Sri Lanka’s geostrategic significance has grown exponentially. Positioned at the crossroads of key maritime trade routes connecting East and West, Sri Lanka occupies a central role in global politics, attracting the attention of global and regional powers alike.

Sri Lanka’s enhanced strategic relevance presents both opportunities and challenges. On the one hand, it allows the country to leverage its geographic advantage for economic development, foreign investment, and diplomatic engagement. On the other hand, it requires careful navigation of complex geopolitical dynamics to maintain strategic autonomy while balancing the competing interests of global powers. In this evolving landscape, Sri Lanka’s foreign policy choices will be instrumental in shaping not only its national trajectory but also broader regional stability in the Indian Ocean.

Pivot to Asia and Indo-Pacific Concept

The emergence of the Indo-Pacific strategic concept reflects the shifting global balance of power towards the Indian Ocean. In response to Asia’s rise, the US recalibrated its approach through the ‘Pivot to Asia’ and ‘Strategic Rebalancing’ under the Obama Administration. While Obama championed the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) as a signature initiative, the Trump administration abandoned it in favour of the ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’ (FOIP) strategy. The Indo-Pacific Strategy Report of the US Department of Defence (2019) asserts: “The United States is a Pacific nation. Our ties to the Indo-Pacific are forged by history, and our future is inextricably linked… The past, present, and future of the United States are interwoven with the Indo-Pacific.” To align with this policy slant, the US Pacific Command (PACOM) renamed itself as the US Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM) in May 2018.

In addition to the United States, India, Australia, and Japan are in the forefront in promoting the concept of Indo-Pacific. Since 2010, Indian political leaders and the strategic community have actively promoted the Indo-Pacific framework. It reinforces the strategic rationale behind India’s Look East, Act East policy and expands its maneuverability beyond the Indian Ocean, aligning with its aspirations as an emerging global power. Under the Indo-Pacific strategic framework, US-India defence relations have reached a new stage, with the INDUS-X, launched on June 20, 2023, to bring together US and Indian stakeholders, including research and academic institutions, industry leaders, startups, and investors, to accelerate and scale up commercial technologies with military applications.

Southeast Asia emerges as the centre of the strategic theatre in the Indo-Pacific strategic construct, while South Asia appears to be positioned further west. At first glance, this shift may suggest a reduced strategic focus on other small states in South Asia like Sri Lanka. In fact, the connectivity of the Pacific and Indian Oceans reinforces the strategic importance of the Indian Ocean, too. Rather than being sidelined, small South Asian states are positioned to benefit from the economic dynamism of Southeast and East Asia through the Indo-Pacific framework.

Sri Lanka remains strategically relevant despite a growing regional focus on Southeast Asia. Its central location ensures continued engagement from major regional and global powers. Sri Lanka’s engagement in Indo-Pacific security discourse, economic frameworks, and infrastructure initiatives will shape its ability to benefit from regional growth while balancing competing strategic interests. Strengthening regional connectivity, trade partnerships, and infrastructure development could unlock new economic opportunities. However, success will depend on Sri Lanka’s ability to navigate regional power dynamics while maintaining strategic autonomy. This highlights the critical role of foreign policy in securing the country’s interests. (To be continued)

by Gamini Keerawella

Features

RIDDHI-MA:

A new Era of Dance in Sri Lanka

Kapila Palihawadana, an internationally renowned dancer and choreographer staged his new dance production, Riddhi-Ma, on 28 March 2025 at the Elphinstone theatre, which was filled with Sri Lankan theatregoers, foreign diplomats and students of dance. Kapila appeared on stage with his charismatic persona signifying the performance to be unravelled on stage. I was anxiously waiting to see nATANDA dancers. He briefly introduced the narrative and the thematic background to the production to be witnessed. According to him, Kapila has been inspired by the Sri Lankan southern traditional dance (Low Country) and the mythologies related to Riddhi Yâgaya (Riddi Ritual) and the black magic to produce a ‘contemporary ballet’.

Riddhi Yâgaya also known as Rata Yakuma is one of the elaborative exorcism rituals performed in the southern dance tradition in Sri Lanka. It is particularly performed in Matara and Bentara areas where this ritual is performed in order to curb the barrenness and the expectation of fertility for young women (Fargnoli & Seneviratne 2021). Kapila’s contemporary ballet production had intermingled both character, Riddi Bisaw (Princes Riddhi) and the story of Kalu Kumaraya (Black Prince), who possesses young women and caught in the evil gaze (yaksa disti) while cursing upon them to be ill (De Munck, 1990).

Kapila weaves a tapestry of ritual dance elements with the ballet movements to create visually stunning images on stage. Over one and a half hours of duration, Kapila’s dancers mesmerized the audience through their virtuosic bodily competencies in Western ballet, Sri Lankan dance, especially the symbolic elements of low country dance and the spontaneity of movements. It is human bodily virtuosity and the rhythmic structures, which galvanised our senses throughout the performance. From very low phases of bodily movements to high speed acceleration, Kapila managed to visualise the human body as an elevated sublimity.

Contemporary Ballet

Figure 2 – (L) Umesha Kapilarathna performs en pointe, and (R) Narmada Nekethani performs with Jeewaka Randeepa, Riddhi-Ma, at Elphinstone Theatre, Maradana, 28th March 2025. Source:

Malshan Witharana

The dance production Riddhi-Ma was choreographed in several segments accompanied by a flow of various music arrangements and sound elements within which the dance narrative was laid through. In other words, Kapila as a choreographer, overcomes the modernist deadlock in his contemporary dance work that the majority of Sri Lankan dance choreographers have very often succumbed to. These images of bodies of female dancers commensurate the narrative of women’s fate and her vulnerability in being possessed by the Black Demon and how she overcomes and emancipates from the oppression. In this sense, Kapila’s dancers have showcased their ability to use the bodies not much as an object which is trained to perform a particular tradition but to present bodily fluidity which can be transformed into any form. Kapila’s performers possess formlessness, fluid fragility through which they break and overcome their bodily regimentations.

It was such a highly sophisticated ‘contemporary ballet’ performed at a Sri Lankan theatre with utmost rigour and precision. Bodies of all male and female dancers were highly trained and refined through classical ballet and contemporary dance. In addition, they demonstrated their abilities in performing other forms of dance. Their bodies were trained to achieve skilful execution of complex ballet movements, especially key elements of traditional ballet namely, improvisation, partnering, interpretation and off-balance and the local dance repertoires. Yet, these key ballet elements are not necessarily a part of contemporary ballet training (Marttinen, 2016). However, it is important for the dance students to learn these key elements of traditional ballet and use them in the contemporary dance settings. In this sense, Kapila’s dancers have achieved such vigour and somatic precision through assiduous practice of the body to create the magic on stage.

Pas de deux

Among others, a particular dance sequence attracted my attention the most. In the traditional ballet lexicon, it is a ‘pas de deux’ which is performed by the ‘same race male and female dancers,’ which can be called ‘a duet’. As Lutts argues, ‘Many contemporary choreographers are challenging social structures and norms within ballet by messing with the structure of the pas de deux (Lutts, 2019). Pas de Deux is a dance typically done by male and female dancers. In this case, Kapila has selected a male and a female dancer whose gender hierarchies appeared to be diminished through the choreographic work. In the traditional pas de deux, the male appears as the backdrop of the female dancer or the main anchorage of the female body, where the female body is presented with the support of the male body. Kapila has consciously been able to change this hierarchical division between the traditional ballet and the contemporary dance by presenting the female dominance in the act of dance.

The sequence was choreographed around a powerful depiction of the possession of the Gara Yakâ over a young woman, whose vulnerability and the powerful resurrection from the possession was performed by two young dancers. The female dancer, a ballerina, was in a leotard and a tight while wearing a pair of pointe shoes (toe shoes). Pointe shoes help the dancers to swirl on one spot (fouettés), on the pointed toes of one leg, which is the indication of the ballet dancer’s ability to perform en pointe (The Kennedy Centre 2020).

The stunning imagery was created throughout this sequence by the female and the male dancers intertwining their flexible bodies upon each other, throwing their bodies vertically and horizontally while maintaining balance and imbalance together. The ballerina’s right leg is bent and her toes are directed towards the floor while performing the en pointe with her ankle. Throughout the sequence she holds the Gara Yakâ mask while performing with the partner.

The male dancer behind the ballerina maintains a posture while depicting low country hand gestures combining and blurring the boundaries between Sri Lankan dance and the Western ballet (see figure 3). In this sequence, the male dancer maintains the balance of the body while lifting the female dancer’s body in the air signifying some classical elements of ballet.

Haptic sense

Figure 3: Narmada Nekathani performs with the Gara Yaka mask while indicating her right leg as en pointe. Male dancer, Jeewaka Randeepa’s hand gestures signify the low country pose. Riddhi-Ma, Dance Theatre at Elphinstone Theatre, 28th March 2025. Source: Malshan Witharana.

One significant element of this contemporary ballet production is the costume design. The selection of colour palette, containing black, red and while combining with other corresponding colours and also the costumes which break the traditional rules and norms are compelling. I have discussed in a recent publication how clothes connect with the performer’s body and operate as an embodied haptic perception to connect with the spectators (Liyanage, 2025). In this production, the costumes operate in two different ways: First it signifies sculpted bodies creating an embodied, empathic experience.

Secondly, designs of costumes work as a mode of three dimensional haptic sense. Kapila gives his dancers fully covered clothing, while they generate classical ballet and Sinhalese ritual dance movements. The covered bodies create another dimension to clothing over bodies. In doing so, Kapila attempts to create sculpted bodies on stage by blurring the boundaries of gender oriented clothing and its usage in Sri Lankan dance.

Sri Lankan female body on stage, particularly in dance has been presented as an object of male desire. I have elsewhere cited that the lâsya or the feminine gestures of the dance repertoire has been the marker of the quality of dance against the tândava tradition (Liyanage, 2025). The theatregoers visit the theatre to appreciate the lâsya bodies of female dancers and if the dancer meets this threshold, then she becomes the versatile dancer. Kandyan dancers such as Vajira and Chithrasena’s dance works are explored and analysed with this lâsya and tândava criteria. Vajira for instance becomes the icon of the lâsya in the Kandyan tradition. It is not my intention here to further discuss the discourse of lâsya and tândava here.

But Kapila’s contemporary ballet overcomes this duality of male-female aesthetic categorization of lâsya and tândava which has been a historical categorization of dance bodies in Sri Lanka (Sanjeewa 2021).

Figure 4: Riddhi-Ma’s costumes creates sculpted bodies combining the performer and the audience through empathic projection. Dancers, Sithija Sithimina and Senuri Nimsara appear in Riddhi-Ma, at Elphinstone Theatre, 28th March 2025, Source, Malshan Witharana.

Conclusion

Dance imagination in the Sri Lankan creative industry exploits the female body as an object. The colonial mind set of the dance body as a histrionic, gendered, exotic and aesthetic object is still embedded in the majority of dance productions produced in the current cultural industry. Moreover, dance is still understood as a ‘language’ similar to music where the narratives are shared in symbolic movements. Yet, Kapila has shown us that dance exists beyond language or lingual structures where it creates humans to experience alternative existence and expression. In this sense, dance is intrinsically a mode of ‘being’, a kinaesthetic connection where its phenomenality operates beyond the rationality of our daily life.

At this juncture, Kapila and his dance ensemble have marked a significant milestone by eradicating the archetypical and stereotypes in Sri Lankan dance. Kapila’s intervention with Riddi Ma is way ahead of our contemporary reality of Sri Lankan dance which will undoubtedly lead to a new era of dance theatre in Sri Lanka.

References

De Munck, V. C. (1990). Choosing metaphor. A case study of Sri Lankan exorcism. Anthropos, 317-328. Fargnoli, A., & Seneviratne, D. (2021). Exploring Rata Yakuma: Weaving dance/movement therapy and a

Sri Lankan healing ritual. Creative Arts in Education and Therapy (CAET), 230-244.

Liyanage, S. 2025. “Arts and Culture in the Post-War Sri Lanka: Body as Protest in Post-Political Aragalaya (Porattam).” In Reflections on the Continuing Crises of Post-War Sri Lanka, edited by Gamini Keerawella and Amal Jayawardane, 245–78. Colombo: Institute for International Studies (IIS) Sri Lanka.

Lutts, A. (2019). Storytelling in Contemporary Ballet.

Samarasinghe, S. G. (1977). A Methodology for the Collection of the Sinhala Ritual. Asian Folklore Studies, 105-130.

Sanjeewa, W. (2021). Historical Perspective of Gender Typed Participation in the Performing Arts in Sri Lanka During the Pre-Colonial, The Colonial Era, and the Post-Colonial Eras. International Journal of Social Science And Human Research, 4(5), 989-997.

The Kennedy Centre. 2020. “Pointe Shoes Dancing on the Tips of the Toes.” Kennedy-Center.org. 2020 https://www.kennedy-center.org/education/resources-for-educators/classroom-resources/media- and-interactives/media/dance/pointe-shoes/..

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Himansi Dehigama for proofreading this article.

About the author:

Saumya Liyanage (PhD) is a film and theatre actor and professor in drama and theatre, currently working at the Department of Theatre Ballet and Modern Dance, Faculty of Dance and Drama, University of the Visual and Performing Arts (UVPA), Colombo. He is the former Dean of the Faculty of Graduate Studies and is currently holding the director position of the Social Reconciliation Centre, UVPA Colombo.

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoColombo Coffee wins coveted management awards

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoDaraz Sri Lanka ushers in the New Year with 4.4 Avurudu Wasi Pro Max – Sri Lanka’s biggest online Avurudu sale

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoStarlink in the Global South

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoStrengthening SDG integration into provincial planning and development process

-

Business4 days ago

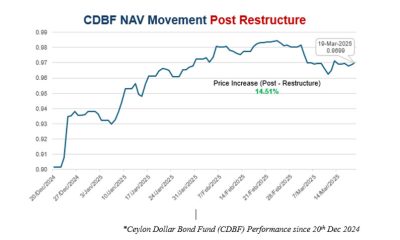

Business4 days agoNew SL Sovereign Bonds win foreign investor confidence

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoTo play or not to play is Richmond’s decision

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoModi’s Sri Lanka Sojourn

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoNew Zealand under 85kg rugby team set for historic tour of Sri Lanka