Features

Marking 125 Years of Chundikuli Girls’ College: Revitalising a Great Heritage

by Rajan Hoole

What Education is about: Think through to the end

In writing for a major anniversary of our school, we affirm its greatness, the good times we had, the eccentricities of the teachers who acted for our own good, the scenery and environment that stay etched in memory; and the achievements of fellow students who made their mark in the world. In the memory of a little boy in the age of innocence, I am awed by the beams of sunlight pouring through the foliage of tall mahoganies that seemed to reach up to the sky. It symbolised the greatness of the institution we were part of. In remembering and reaffirming this in the company of old students from all parts of the wide world, we assure ourselves of our place in it and it is no mean corner of it that is ours. I indulged in such thoughts when I wrote 25 years ago, but that seems out of place against present reality.

I now write as one of the exceptions in my class, whether at Chundikuli or St. John’s, that actually lives in Jaffna. Many people in this country, in view of the past tragic decades have decided this is not the place for their children. Being at the tail end of the Psalmist’s life span, I see very few of my old mates. A number of them came to Jaffna after the war ended to reclaim their properties, smiled, exchanged pleasantries with old friends, or thanked those who had protected their belongings and said their last good-byes after getting the best prices for their land, often to the detriment of those left behind.

Many would claim that they had no alternative, but there should be no pretence that they left behind a healthy society and schools, and share no responsibility for the fate of a people who were their neighbours for generations. On the surface things could appear normal, but behind it lurks loneliness, absence of civic sense, coupled with a fear of going beyond personal interest and standing up for what one believes is right and decent.

It has a debilitating effect on education. Another writer in this series has referred to my mother Jeevamany Somasundaram, an old girl of Chundikuli who sat for her Cambridge Senior (O Levels) about 1934. A story that moved me deeply was related by my piano teacher Miss. Abbey Hunt. She said that during lunch intervals, when the girls were amusing themselves with various pursuits, my mother sat beneath a mahogany tree, working riders in Euclidian Geometry. It was an injunction setting a standard: once you take a problem in hand, think it through to the end. It is not a story about one woman, but about a school, an atmosphere, the teachers and their personal interest that challenged students to a high level of intellectual rigor.

Until about the 1970s several schools in Jaffna had teachers who identified capable students and took a keen interest in their future. A student of my age at Hartley told me that his Mathematics teacher, R.M. Gunaratnam, once caught him in a vice-like grip in Pt. Pedro town and warned him about his absence from classes. Today that link between teachers and students has greatly diminished, and teaching has largely been sub-contracted to tutories. It has led to a marked fall in intellectual standards and the near disappearance of intellectual life in Jaffna.

Tutories are not about teaching students to think, but produce good grades in A. Levels. My experience in university teaching too has been that few students attempt tutorial questions, but wait for answers to be given in class. It has resulted in a culture of not wanting to think through a problem. The university training amounts to teaching people to apply formulae and get results, and not bother with foundations. Many of them emigrate and get jobs abroad, which makes me suspect that we are good at producing engineer-clerks and doctor-clerks who perform their routines quite well.

Tutories are not about teaching students to think, but produce good grades in A. Levels. My experience in university teaching too has been that few students attempt tutorial questions, but wait for answers to be given in class. It has resulted in a culture of not wanting to think through a problem. The university training amounts to teaching people to apply formulae and get results, and not bother with foundations. Many of them emigrate and get jobs abroad, which makes me suspect that we are good at producing engineer-clerks and doctor-clerks who perform their routines quite well.

Leaving behind a desert

I have referred to the ongoing sale of expatriate properties in Jaffna, which are followed by the capricious appearance of high rise buildings and the disappearance of tanks and drains. Common sense points to danger. The most damning indicator was the flooding of Jaffna Hospital during the last rains when medical staff and patients were knee-deep in water.

Coming to the issue of thinking a problem through to the end, the building spree in Jaffna has been promoted by persons in authority promising modernised water, drainage and sewage systems for Jaffna. When there is prospect of huge foreign loans, perks and contracts, basic constraints are swept under the carpet. Foreign experts are all for it and, and of our own experts who sold it, few will ultimately be rooted in Jaffna. Novel possibilities were talked about for many years and dropped; such as desalination in Vadamaratchi East, water from Iranamadu Tank for Jaffna only in flood years, or finding new sources, all of which showed that something was wrong at the root of the idea. I must digress a little.

Iranamadu has an average inflow of 147 MCM (Mega Cubic Metres), adequate for cultivation of 95 percent of paddy in Winter and 30 percent in Summer (World Bank, 1984). Supplying Jaffna means pinching 10 MCM of inflow to be piped out. A very basic constraint can be worked out from variations in river flow studied by older professionals like R. Sakthivadivel. The studies which are available on the web have been ignored. I worked out in my book Palmyra Fallen (2015) commemorating Dr. Rajani Thiranagama, that the 75 percent reliable flow into Iranamadu is 80 MCM. Nature has a cycle of about four years, and once in those four years (25 percent of the time), you could get 80 MCM or less, even though the average is 147 MCM.

In such lean years sending 10 MCM to Jaffna would be very hard on the local farmer. There are years of severe flooding but that excess has to be allowed to run to the sea. That is the short explanation of the problem. Funds were rolled out, pipes were sunk and holding towers were built. Going by press reports the matter has been at standstill from before 13 January 2019 (Sunday Observer), against protests in Killinochchi.

Although we had some of Jaffna’s leading professionals on the job, they did not think the problem through. They simply defined the problem as water being available at Iranamadu (the average inflow) and laying the works for piping it to Jaffna. The cyclical variations of river flow (Kanagarayan Aru) were simply ignored by those who should have known best.

The problem comes down to present-day Jaffna lacking an educated critical mass with the motivation, ability and connections to look after their basic interests like a clean environment and drinking water. Those with money and power have their interests elsewhere. The problems faced by many residents in Jaffna are not dissimilar to those of civilians in Rathupaswala, Gampaha, three of whom were killed on August 1, 2013 over their protest for clean drinking water.

One Jaffna family saw a hotel and a high rise building coming up on the lands of well-to-do former neighbours, which they had looked after during the war. Prices offered from black money were what their left-behind neighbours could not match. The well water in the area remains undrinkable or murky in addition to noise pollution. In the absence of a sewage system they do not know how human waste is being disposed of. Excessive drawing of water from one urban well could cause others in the neighbourhood to run dry.

Black money came, according to the well informed grapevine, in post war years from funds connected to the departing rulers held by selected businessmen. In time this black money made connections to political and similar funds in the South and in an unhealthy way fills the present gap our once independent institutions are unable to fill, particularly in health and education.

The Church that sustained Jaffna’s premier institutions in education and health fell victim to emigration and division. There is no local vision or qualified presence in Jaffna to sustain the education up to tertiary level and the medical network it pioneered. Money-centred education and medicine have thrown up a class of nouveau riche, whose impact could be classed along with that of black money.

Absence of a civic voice for Jaffna

Between Chundikuli and St. John’s, it was C.E. Anandarajah who, as principal, stood forthright as a leading voice of civil concerns in Jaffna until he was killed by the LTTE in 1985. I see the two schools as having remained timid on social concerns since. Chundikuli produced in Dr. Rajani Thiranagama a rare voice of defiance, courage and compassion, whom I was close to in the path-breaking finale of her activism ending with her assassination by the LTTE in 1989. Her civic sense as a doctor led her to treat an LTTE injured when no one else could be found. She then became involved with the LTTE. Having then become disgusted with its inhumanity, she stood up and challenged it in Jaffna itself out of compassion for those it was destroying. What she was up against is illustrated by elite politics in a society that still extols an ideology; one that in its last stand in 2009 held hostage 300,000 civilians under fire, in order to strike a deal for the safety of its leaders.

Between Chundikuli and St. John’s, it was C.E. Anandarajah who, as principal, stood forthright as a leading voice of civil concerns in Jaffna until he was killed by the LTTE in 1985. I see the two schools as having remained timid on social concerns since. Chundikuli produced in Dr. Rajani Thiranagama a rare voice of defiance, courage and compassion, whom I was close to in the path-breaking finale of her activism ending with her assassination by the LTTE in 1989. Her civic sense as a doctor led her to treat an LTTE injured when no one else could be found. She then became involved with the LTTE. Having then become disgusted with its inhumanity, she stood up and challenged it in Jaffna itself out of compassion for those it was destroying. What she was up against is illustrated by elite politics in a society that still extols an ideology; one that in its last stand in 2009 held hostage 300,000 civilians under fire, in order to strike a deal for the safety of its leaders.

I began with the importance of educational training that urges one to spare no effort in thinking a problem through. It applies equally to the state of our politics. There was no strong resistance in Jaffna society when G.G. Ponnambalam, who was our leader in 1948, cooperated with Prime Minister Senanayake in nullifying the rights of Up Country Tamils. Ponnambalam was only following the line of several notables from the North; many of them not his supporters (A.J. Wilson, Political Biography of Chelvanayakam). The damage we did to the Up Country Tamils hurt us grievously in the long term. Since then we have been crying over spilt milk – the large numbers of dead and the exile of our brightest and best to Austro-eur-america.

Our fragmentation and growing isolation is reflected in queries about how the dowry of a bride from Jaffna would translate into real estate in Colombo or Sydney. We cannot stop at observing that we have been poorly served by most of those who left us. The present girls of Chundikuli have as much talent as there was in the time of our mothers and aunts. What they need is to rediscover the tradition that questions everything they are told and reason them out to the end. I don’t think I am wrong when I say that what made Jaffna great in the 1930s and 1940s was the strong surge of sympathy for the Indian independence struggle. That was when the influence of Gandhi and liberated women like Kamaladevi Chattopadyaya and Sarojini Naidu, all of whom came to Jaffna, made a tremendous impact on its people.

My mother spoke of her teachers with great affection. When she was on the staff of the school and was engaged in 1947, the Principal Dr. Miss. Evangeline Thilliayampalam (PhD Columbia, 1929, aged 34) counselled her that an engagement should not be prolonged. Her Jubilee message in 1946 points to a woman who was silently politicised: “The forces which retard human progress are poverty, ignorance and class rivalry.” My mother also spoke fondly of the Mutthiah sisters, Kanaham and Yogam. I quote from Lorna Vandendriesen who said in a tribute to three Chundikuli teachers, ‘who really set high standards and ran the school regardless of who was the Principal. Gracious Miss. Grace Hensman, gentle Miss. Kanaham Mutthiah and beautiful Miss. Yogam. They were wonderful teachers. I know. I was their pupil.’

I.P. Thurairatnam, who was later principal of Union College, said that he won the ‘Mixed Doubles Championship with Yogam Muttiah of Chundikuli. Spurred by these victories we tried our mettle at the All Ceylon Tennis Meet in Nuwara Eliya in 1932 and 1933, and met with moderate success.’ Chundikuli girls long had a reputation as trend setters.

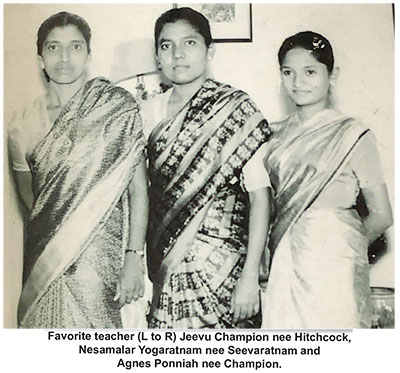

I may add that admitted to Chundikuli as a boy of seven I spent two golden years as a novice to the world of the fairer sex (1956/7). I too was pleasantly affected by my charming class teachers Miss. Nesamalar Seevaratnam (now Mrs. Yogaratnam) and Miss. Agnes Champion (later Mrs. Ponniah).

Today’s Jaffna could be a very discouraging place. In order to sharpen our analytical ability and think problems through without resting satisfied with half-baked solutions we need public discussion, friends and colleagues who would tell us bluntly when we are being asinine. When we become defensive and take offence at criticism, even a well-endowed institution like a university would fail to prepare students to think through problems and aspire to a just society, while the teachers themselves remain frogs-in-the-well.

We cannot change things overnight, but what well-wishers could do for schools like Chundikuli is to expose students to speakers who will encourage them to question everything. This we used to have in the 1950s and 1960s when visitors from India were frequent. It also means reversing swabasha isolationism.

Features

Hanoi’s most popular street could kill you

Train Street started life as a razor-thin alley with a train rushing through it. Now, it’s swarmed with Instagrammable cafes and tourists who can’t stay away, despite the risks.

A train chugs through Hanoi, approaching a narrow passageway festooned with Chinese-style lanterns. Just as it screams into the station, a tourist jumps onto the tracks, attempting her most social-media friendly pose. Moments before the train strikes, its horn blaring into the humid air, she recoils to safety. Click, post.

It’s just an ordinary day on Hanoi’s Train Street, a 400m stretch of railway flanked by cafes where tourists nurse beers and watch, mesmerised, as trains roar past them at dangerously close proximity: sometimes crashing into tables and chairs.

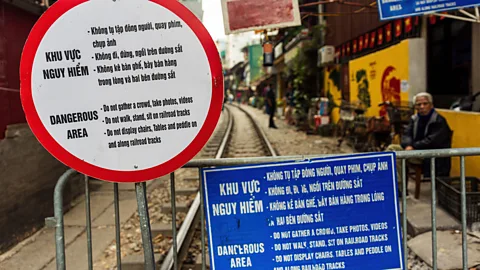

Fun? Evidently – in a few short years, Train Street has entered Vietnam’s pantheon of “must-see” attractions, along with Ha Long Bay and the Cu Chi Tunnels. But the Vietnamese government is less impressed; since the site went viral in 2017, it has attempted various shutdowns, first in 2019, then 2022 and most recently further investigations and crackdowns in 2025 after an incident where a selfie-snapping tourist was nearly dragged under an oncoming train’s wheels. Police barricades go up between train arrivals; edicts are issued to tour operators and bar owners.

The tourists come anyway.

How did an ordinary street become one of Vietnam’s hottest tourist attractions? It started innocently enough.

The North-South Railway was built by colonialist French forces in 1902, connecting Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City. Fifty-four years later, the General Department of Railway erected a series of squat buildings straddling a stretch in central Hanoi to house employees. By the 1970s, the area was considered a slum; residents regularly roused out of their sleep by trains rumbling through, their houses quaking.

“It was just an ordinary street with train tracks running through it,” said Minh Anh, a lifelong Hanoi local who works at local whisky distillery,

Alamy The Vietnamese government has attempted numerous shutdowns of the area (Credit: Alamy)Alamy

The Vietnamese government has attempted numerous shutdowns of the area (Credit: Alamy)

From ordinary to unmissable

How did an ordinary street become one of Vietnam’s hottest tourist attractions? It started innocently enough.

The North-South Railway was built by colonialist French forces in 1902, connecting Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City. Fifty-four years later, the General Department of Railway erected a series of squat buildings straddling a stretch in central Hanoi to house employees. By the 1970s, the area was considered a slum; residents regularly roused out of their sleep by trains rumbling through, their houses quaking.

“It was just an ordinary street with train tracks running through it,” said Minh Anh, a lifelong Hanoi local who works at local whisky distillery, Về Để Đi’. “When it started popping up all over social media, I was honestly surprised.”

Nhi Nguyn, a tour guide for A Taste of Hanoi, used to walk tourists through, just before it exploded in popularity. “People were still living ordinary lives there back then and there weren’t so many cafes next to the tracks,” she said. “It had a much more authentic feel: scooters were locked up just meters from the tracks, laundered clothes hung outside, and people were cooking outside on small gas stoves.”

. “When it started popping up all over social media, I was honestly surprised.”

Nhi Nguyn, a tour guide for

Alamy The Vietnamese government has attempted numerous shutdowns of the area (Credit: Alamy)Alamy

The Vietnamese government has attempted numerous shutdowns of the area (Credit: Alamy)

From ordinary to unmissable

How did an ordinary street become one of Vietnam’s hottest tourist attractions? It started innocently enough.

The North-South Railway was built by colonialist French forces in 1902, connecting Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City. Fifty-four years later, the General Department of Railway erected a series of squat buildings straddling a stretch in central Hanoi to house employees. By the 1970s, the area was considered a slum; residents regularly roused out of their sleep by trains rumbling through, their houses quaking.

“It was just an ordinary street with train tracks running through it,” said Minh Anh, a lifelong Hanoi local who works at local whisky distillery, Về Để Đi’. “When it started popping up all over social media, I was honestly surprised.”

Nhi Nguyn, a tour guide for A Taste of Hanoi, used to walk tourists through, just before it exploded in popularity. “People were still living ordinary lives there back then and there weren’t so many cafes next to the tracks,” she said. “It had a much more authentic feel: scooters were locked up just meters from the tracks, laundered clothes hung outside, and people were cooking outside on small gas stoves.”

, used to walk tourists through, just before it exploded in popularity. “People were still living ordinary lives there back then and there weren’t so many cafes next to the tracks,” she said. “It had a much more authentic feel: scooters were locked up just meters from the tracks, laundered clothes hung outside, and people were cooking outside on small gas stoves.”

In early 2013, Colm Pierce and Alex Sheal, co-founders of Hanoi-based photography tours Vietnam in Focus, launched a Hanoi on the Tracks tour to show visitors how local residents had adopted to the locomotive-sized challenge of living on railway tracks. Serendipitously, in June 2013, Instagram launched its new video-sharing feature. A year later, the Travel Channel show “Tough Trains” featured Pierce walking down Train Street with a camera crew, further enticing travellers.

In 2017, an enterprising resident started selling beer and coffee, inviting curious tourists to stay to watch the train go by. Neighbours noticed the economic opportunity and cafes and bars rapidly spread. Soon, the formerly derelict alley, now dubbed Phố Đường Tàu (literally: “Train Street”) became bedecked with colourful lanterns and Christmas lights. Visitors learned to time their arrival for 30 minutes before a scheduled train and the “classic” Train Street experience was cemented: upon entering the tracks, tourists were shepherded into rail-side bars by local merchants and plied with beers and coffee, until the train shrieked through, rattling plates and causing hearts to pound.

Julia Husum, a university student from Norway, visited Train Street in February 2026, and “loved” the experience. “We put our beer caps on the railway, and the train flattened it, creating souvenirs for us,” she said. “I’d go back again.”

Without the advent of social media, would Train Street have become popular? As a travel writer, I’ve witnessed dozens of would-be influencers’ death-defying acts, like scaling down a rocky cliff above Dubrovnik and standing atop the side wall of 14th-Century Charles Bridge in Prague; wistfully looking off into the distance as the camera flashes. I’ve come to conclude that Train Street is no different; here, too, visitors risk their own safety for a picture-perfect opportunity.

“Essentially social media has fuelled Train Street into what it is today, [where] tourists flock in droves to the area to feel the adrenaline of the passing train while sipping local coffee,” echoed Michael Stanbury, the creative director for Vietnam in Focus. “Even without the train, the Instagrammable decorated street holds a very Hanoian charm.”

Local debate; the government proposes halting passenger trains for good. And each attempted shutdown, tourists climb past the barricades. There are, to date, more than 100,000 posts tagging Train Street on Instagram. Men’s grooming blogger Adam Hurly visited because a friend had hyped it. “It felt more like an Instagram attraction rather than a neighbourhood street,” he admitted, noting that once the crowds arrive, it becomes congested and less enjoyable, “Especially if you’re just standing on the main sidewalk trying to get a picture.”

He added: “It’s one of those places that looks better in photos than it feels in reality.”

But Matthew Tran, an artisanal footwear designer who visits Hanoi regularly, loves the pull of Train Street.

“The coffees were absurdly overpriced, yet I paid for them every time because I couldn’t stop marvelling at how the place worked; how an entire economy could thrive in such an improbable space,” he said. “These vendors built something real out of something most people would call chaos – that, to me, is worth coming back for.”

He offers advice for future visitors: “It’s a unique experience you won’t get anywhere else. Although I wish more visitors would stop for a moment and remember that while it’s a tourist attraction to them, living beside those train tracks is someone else’s daily reality.”

Under more superficial reasons, visiting Train Street is similar to the appeal of visiting the Eiffel Tower during someone’s first visit to Paris, said Charlotte Russell, founder of The Travel Psychologist.

“Humans are a social species and if we perceive that other people are enjoying an experience, it is natural for us to want to do it too,” she said. “This goes back to our evolution, when we lived in small groups and it would be advantageous for us to emulate other people in this way. So the sense of fear of missing out that we experience when seeing other people visiting places like Train Street is part of being human.”

Bearix Stewart-Frommer, an American pre-med student, validates Russell’s theory: “I found out about Train Street from my mum,” she said. “I didn’t have some deep motivation to see it, but I was curious because it’s one of those quirky, very photogenic spots that people talk about on social media.”

But there may be a more deep-seated reason why we’re lured to such places, Russell notes: “With Train Street specifically, the risk element is part of what makes it so novel, especially those of us from countries like the UK… We are used to regulation and precaution, railings, barriers and painted lines that we must stand behind. In contrast, Train Street can feel unbelievable to see and experience… [it helps] us reflect on our own norms and realise that other perspectives do exist.”

Local tour guide Phuong Loan Ngo offers one such alternative perspective: “The economic boost is undeniable, giving families who live along Train Street financial opportunities,” she said. “On the other hand, there are cultural challenges too. When an area becomes a ‘spotlight’ for social media, a place’s historical and cultural heritage can get lost. Instead of learning about how this railway has functioned since the colonial era, people often leave with only a photo, missing the true soul of the neighbourhood.”

The irony is that Vietnam in Focus has now moved their photography tours to another, far-less trammelled part of the railway, so they can show visitors that old, track-side way of life.

“As with all good things, the popularity of Train Street and the crowds it attracts are spreading,” said Sheal. “Thankfully, we have scoured Hanoi and found a fantastic local market that runs along the Hanoian railway further out in the suburbs – a new attraction.”

That is, until the social-media-obsessed travel masses find out about it. For better or worse, the unbearable lightness of Train Street is a permanent, but moveable feast.

[BBC]

Features

An innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

After nearly two decades of on-and-off negotiations that began in 2007, India and the European Union formally finally concluded a comprehensive free trade agreement on 27 January 2026. This agreement, the India–European Union Free Trade Agreement (IEUFTA), was hailed by political leaders from both sides as the “mother of all deals,” because it would create a massive economic partnership and greatly increase the current bilateral trade, which was over US$ 136 billion in 2024. The agreement still requires ratification by the European Parliament, approval by EU member states, and completion of domestic approval processes in India. Therefore, it is only likely to come into force by early 2027.

An Innocent Bystander

When negotiations for a Free Trade Agreement between India and the European Union were formally launched in June 2007, anticipating far-reaching consequences of such an agreement on other developing countries, the Commonwealth Secretariat, in London, requested the Centre for Analysis of Regional Integration at the University of Sussex to undertake a study on a possible implication of such an agreement on other low-income developing countries. Thus, a group of academics, led by Professor Alan Winters, undertook a study, and it was published by the Commonwealth Secretariat in 2009 (“Innocent Bystanders—Implications of the EU-India Free Trade Agreement for Excluded Countries”). The authors of the study had considered the impact of an EU–India Free Trade Agreement for the trade of excluded countries and had underlined, “The SAARC countries are, by a long way, the most vulnerable to negative impacts from the FTA. Their exports are more similar to India’s…. Bangladesh is most exposed in the EU market, followed by Pakistan and Sri Lanka.”

Trade Preferences and Export Growth

Normally, reduction of price through preferential market access leads to export growth and trade diversification. During the last 19-year period (2015–2024), SAARC countries enjoyed varying degrees of preferences, under the EU’s Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP). But, the level of preferential access extended to India, through the GSP (general) arrangement, only provided a limited amount of duty reduction as against other SAARC countries, which were eligible for duty-free access into the EU market for most of their exports, via their LDC status or GSP+ route.

However, having preferential market access to the EU is worthless if those preferences cannot be utilised. Sri Lanka’s preference utilisation rate, which specifies the ratio of eligible to preferential imports, is significantly below the average for the EU GSP receiving countries. It was only 59% in 2023 and 69% in 2024. Comparative percentages in 2024 were, for Bangladesh, 96%; Pakistan, 95%; and India, 88%.

As illustrated in the table above, between 2015 and 2024, the EU’s imports from SAARC countries had increased twofold, from US$ 63 billion in 2015 to US$ 129 billion by 2024. Most of this growth had come from India. The imports from Pakistan and Bangladesh also increased significantly. The increase of imports from Sri Lanka, when compared to other South Asian countries, was limited. Exports from other SAARC countries—Afghanistan, Bhutan, Nepal, and the Maldives—are very small and, therefore, not included in this analysis.

Why the EU – India FTA?

With the best export performance in the region, why does India need an FTA with the EU?

Because even with very impressive overall export growth, in certain areas, India has performed very poorly in the EU market due to tariff disadvantages. In addition to that, from January 2026, the EU has withdrawn GSP benefits from most of India’s industrial exports. The FTA clearly addresses these challenges, and India will improve her competitiveness significantly once the FTA becomes operational.

Then the question is, what will be its impact on those “innocent bystanders” in South Asia and, more particularly, on Sri Lanka?

To provide a reasonable answer to this question, one has to undertake an in-depth product-by-product analysis of all major exports. Due to time and resource constraints, for the purpose of this article, I took a brief look at Sri Lanka’s two largest exports to the EU, viz., the apparels and rubber-based products.

Fortunately, Sri Lanka’s exports of rubber products will be only nominally impacted by the FTA due to the low MFN duty rate. For example, solid tyres and rubber gloves are charged very low (around 3%) MFN duty and the exports of these products from Sri Lanka and India are eligible for 0% GSP duty at present. With an equal market access, Sri Lanka has done much better than India in the EU market. Sri Lanka is the largest exporter of solid tyres to the EU and during 2024 our exports were valued at US$180 million.

On the other hand, Tariffs MFN tariffs on Apparel at 12% are relatively high and play a big role in apparel sourcing. Even a small difference in landed cost can shift entire sourcing to another supplier country. Indian apparel exports to the EU faced relatively high duties (8.5% – 12%), while competitors, such as Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, are eligible for preferential access. In addition to that, Bangladesh enjoys highly favourable Rules of Origin in the EU market. The impact of these different trade rules, on the EU’s imports, is clearly visible in the trade data.

During the last 10 years (2015-2024), the EU’s apparel imports from Bangladesh nearly doubled, from US$15.1 billion, in 2015, to US$29.1 billion by 2024, and apparel imports from Pakistan more than doubled, from US$2.3 billion to US$5.5 billion. However, apparel imports from Sri Lanka increased only from US$1.3 billion in 2015 to US$2.2 billion by 2024. The impressive export growth from Pakistan and Bangladesh is mostly related to GSP preferences, while the lackluster growth of Sri Lankan exports was largely due to low preference utilisation. Nearly half of Sri Lanka’s apparel exports faced a 12% tariff due to strict Rules of Origin requirements to qualify for GSP.

During the same period, the EU’s apparel imports from India only showed very modest growth, from US$ 5.3 billion, in 2015, to US$ 6.3 billion in 2024. The main reason for this was the very significant tariff disadvantage India faced in the EU market. However, once the FTA eliminates this gap, apparel imports from India are expected to grow rapidly.

According to available information, Indian industry bodies expect US$ 5-7 billion growth of textiles and apparel exports during the first three years of the FTA. This will create a significant trade diversion, resulting in a decline in exports from China and other countries that do not enjoy preferential market access. As almost half of Sri Lanka’s apparel exports are not eligible for GSP, the impact on our exports will also be fierce. Even in the areas where Sri Lanka receives preferential duty-free access, the arrival of another large player will change the market dynamics greatly.

A Passive Onlooker?

Since the commencement of the negotiations on the EU–India FTA, Bangladesh and Pakistan have significantly enhanced the level of market access through proactive diplomatic interventions. As a result, they have substantially increased competitiveness and the market share within the EU. This would help them to minimize the adverse implications of the India–EU FTA on their exports. Sri Lanka’s exports to the EU market have not performed that well. The challenges in that market will intensify after 2027.

As we can clearly anticipate a significant adverse impact from the EU-India FTA, we should start to engage immediately with the European Commission on these issues without being passive onlookers. For example, the impact of the EU-India FTA should have been a main agenda item in the recently concluded joint commission meeting between the European Commission and Sri Lanka in Colombo.

Need of the Hour – Proactive Commercial Diplomacy

In the area of international trade, it is a time of turbulence. After the US Supreme Court judgement on President Trump’s “reciprocal tariffs,” the only prediction we can make about the market in the United States market is its continued unpredictability. India concluded an FTA with the UK last May and now the EU-India FTA. These are Sri Lanka’s largest markets. Now to navigate through these volatile, complex, and rapidly changing markets, we need to move away from reactive crisis management mode to anticipatory action. Hence, proactive commercial diplomacy is the need of the hour.

(The writer can be reached at senadhiragomi@gmail.com)

By Gomi Senadhira

Features

Educational reforms: A perspective

Dr. B.J.C. Perera (Dr. BJCP) in his article ‘The Education cross roads: Liberating Sri Lankan classroom and moving ahead’ asks the critical question that should be the bedrock of any attempt at education reform – ‘Do we truly and clearly understand how a human being learns? (The Island, 16.02.2026)

Dr. BJCP describes the foundation of a cognitive architecture taking place with over a million neural connections occurring in a second. This in fact is the result of language learning and not the process. How do we ‘actually’ learn and communicate with one another? Is a question that was originally asked by Galileo Galilei (1564 -1642) to which scientists have still not found a definitive answer. Naom Chomsky (1928-) one of the foremost intellectuals of our time, known as the father of modern linguistics; when once asked in an interview, if there was any ‘burning question’ in his life that he would have liked to find an answer for; commented that this was one of the questions to which he would have liked to find the answer. Apart from knowing that this communication takes place through language, little else is known about the subject. In this process of learning we learn in our mother tongue and it is estimated that almost 80% of our learning is completed by the time we are 5 years old. It is critical to grasp that this is the actual process of learning and not ‘knowledge’ which tends to get confused as ‘learning’. i.e. what have you learnt?

The term mother tongue is used here as many of us later on in life do learn other languages. However, there is a fundamental difference between these languages and one’s mother tongue; in that one learns the mother tongue- and how that happens is the ‘burning question’ as opposed to a second language which is taught. The fact that the mother tongue is also formally taught later on, does not distract from this thesis.

Almost all of us take the learning of a mother tongue for granted, as much as one would take standing and walking for granted. However, learning the mother tongue is a much more complex process. Every infant learns to stand and walk the same way, but every infant depending on where they are born (and brought up) will learn a different mother tongue. The words that are learnt are concepts that would be influenced by the prevalent culture, religion, beliefs, etc. in that environment of the child. Take for example the term father. In our culture (Sinhala/Buddhist) the father is an entity that belongs to himself as well as to us -the rest of the family. We refer to him as ape thaththa. In the English speaking (Judaeo-Christian) culture he is ‘my father’. ‘Our father’ is a very different concept. ‘Our father who art in heaven….

All over the world education is done in one’s mother tongue. The only exception to this, as far as I know, are the countries that have been colonised by the British. There is a vast amount of research that re-validates education /learning in the mother tongue. And more to the point, when it comes to the comparability of learning in one’s own mother tongue as opposed to learning in English, English fails miserably.

Education /learning is best done in one’s mother tongue.

This is a fact. not an opinion. Elegantly stated in the words of Prof. Tove Skutnabb-Kangas-“Mother tongue medium education is controversial, but ‘only’ politically. Research evidence about it is not controversial.”

The tragedy is that we are discussing this fundamental principle that is taken for granted in the rest of the world. It would not be not even considered worthy of a school debate in any other country. The irony of course is, that it is being done in English!

At school we learnt all of our subjects in Sinhala (or Tamil) right up to University entrance. Across the three streams of Maths, Bio and Commerce, be it applied or pure mathematics, physics, chemistry, zoology, botany economics, business, etc. Everything from the simplest to the most complicated concept was learnt in our mother tongue. An uninterrupted process of learning that started from infancy.

All of this changed at university. We had to learn something new that had a greater depth and width than anything we had encountered before in a language -except for a very select minority – we were not at all familiar with. There were students in my university intake that had put aside reading and writing, not even spoken English outside a classroom context. This I have been reliably informed is the prevalent situation in most of the SAARC countries.

The SAARC nations that comprise eight countries (Sri Lanka, Maldives, India, Pakistan Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Bhutan) have 21% of the world population confined to just 3% of the earth’s land mass making it probably one of the most densely populated areas in the world. One would assume that this degree of ‘clinical density’ would lead to a plethora of research publications. However, the reality is that for 25 years from 1996 to 2021 the contribution by the SAARC nations to peer reviewed research in the field of Orthopaedics and Sports medicine- my profession – was only 1.45%! Regardless of each country having different mother tongues and vastly differing socio-economic structures, the common denominator to all these countries is that medical education in each country is done in a foreign language (English).

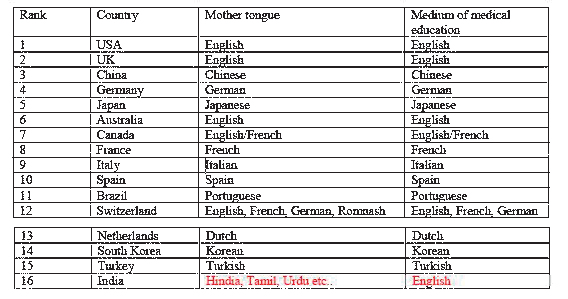

The impact of not learning in one’s mother tongue can be illustrated at a global level. This can be easily seen when observing the research output of different countries. For example, if one looks at orthopaedics and sports medicine (once again my given profession for simplicity); Table 1. shows the cumulative research that has been published in peer review journals. Despite now having the highest population in the world, India comes in at number 16! It has been outranked by countries that have a population less than one of their states. Pundits might argue giving various reasons for this phenomenon. But the inconvertible fact remains that all other countries, other than India, learn medicine in their mother tongue.

(See Table 1) Mother tongue, medium of education in country rank order according to the volume of publications of orthopaedics and sports medicine in peer reviewed journals 1996 to 2024. Source: Scimago SCImago journal (https://www.scimagojr.com/) has collated peer review journal publications of the world. The publications are categorized into 27 categories. According to the available data from 1996 to 2024, China is ranked the second across all categories with India at the 6th position. China is first in chemical engineering, chemistry, computer science, decision sciences, energy, engineering, environmental science, material sciences, mathematics, physics and astronomy. There is no subject category that India is the first in the world. China ranks higher than India in all categories except dentistry.

The reason for this difference is obvious when one looks at how learning is done in China and India.

The Chinese learn in their mother tongue. From primary to undergraduate and postgraduate levels, it is all done in Chinese. Therefore, they have an enormous capacity to understand their subject matter just not itself, but also as to how it relates to all other subjects/ themes that surround it. It is a continuous process of learning that evolves from infancy onwards, that seamlessly passes through, primary, secondary, undergraduate and post graduate education, research, innovation, application etc. Their social language is their official language. The language they use at home is the language they use at their workplaces, clubs, research facilities and so on.

In India higher education/learning is done in a foreign language. Each state of India has its own mother tongue. Be it Hindi, Tamil, Urdu, Telagu, etc. Infancy, childhood and school education to varying degrees is carried out in each state according to their mother tongue. Then, when it comes to university education and especially the ‘science subjects’ it takes place in a foreign tongue- (English). English remains only as their ‘research’ language. All other social interactions are done in their mother tongue.

India and China have been used as examples to illustrate the point between learning in the mother tongue and a foreign tongue, as they are in population terms comparable countries. The unpalatable truth is that – though individuals might have a different grasp of English- as countries, the ability of SAARC countries to learn and understand a subject in a foreign language is inferior to the rest of the world that is learning the same subject in its mother tongue. Imagine the disadvantage we face at a global level, when our entire learning process across almost all disciplines has been in a foreign tongue with comparison to the rest of the world that has learnt all these disciplines in their mother tongue. And one by-product of this is the subsequent research, innovation that flows from this learning will also be inferior to the rest of the world.

All this only confirms what we already know. Learning is best done in one’s mother tongue! .

What needs to be realised is that there is a critical difference between ‘learning English’ and ‘learning in English’. The primary-or some may argue secondary- purpose of a university education is to learn a particular discipline, be it medicine, engineering, etc. The students- have been learning everything up to that point in Sinhala or Tamil. Learning their discipline in their mother tongue will be the easiest thing for them. The solution to this is to teach in Sinhala or Tamil, so it can be learnt in the most efficient manner. Not to lament that the university entrant’s English is poor and therefore we need to start teaching English earlier on.

We are surviving because at least up to the university level we are learning in the best possible way i.e. in our mother tongue. Can our methods be changed to be more efficient? definitely. If, however, one thinks that the answer to this efficient change in the learning process is to substitute English for the mother tongue, it will defeat the very purpose it is trying to overcome. According to Dr. BJCP as he states in his article; the current reforms of 2026 for the learning process for the primary years, centre on the ‘ABCDE’ framework: Attendance, Belongingness, Cleanliness, Discipline and English. Very briefly, as can be seen from the above discussion, if this is the framework that is to be instituted, we should modify it to ABCDEF by adding a F for Failure, for completeness!

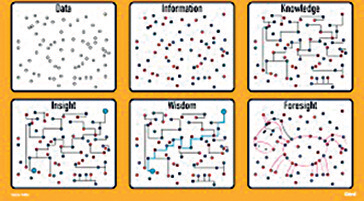

(See Figure 1) The components and evolution of learning: Data, information, knowledge, insight, wisdom, foresight As can be seen from figure 1. data and information remain as discrete points. They do not have interconnections between them. It is these subsequent interconnections that constitute learning. And these happen best through the mother tongue. Once again, this is a fact. Not an opinion. We -all countries- need to learn a second language (foreign tongue) in order to gather information and data from the rest of the world. However, once this data/ information is gathered, the learning needs to happen in our own mother tongue.

Without a doubt English is the most universally spoken language. It is estimated that almost a quarter of the world speaks English as its mother tongue or as a second language. I am not advocating to stop teaching English. Please, teach English as a second language to give a window to the rest of the world. Just do not use it as the mode of learning. Learn English but do not learn in English. All that we will be achieving by learning in English, is to create a nation of professionals that neither know English well nor their subject matter well.

If we are to have any worthwhile educational reforms this should be the starting pivotal point. An education that takes place in one’s mother tongue. Not instituting this and discussing theories of education and learning and proposing reforms, is akin to ‘rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic’. Sadly, this is not some stupendous, revolutionary insight into education /learning. It is what the rest of the world has been doing and what we did till we came under British rule.

Those who were with me in the medical faculty may remember that I asked this question then: Why can’t we be taught in Sinhala? Today, with AI, this should be much easier than what it was 40 years ago.

The editorial of this newspaper has many a time criticised the present government for its lackadaisical attitude towards bringing in the promised ‘system change’. Do this––make mother tongue the medium of education /learning––and the entire system will change.

by Dr. Sumedha S. Amarasekara

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoReconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoVictor Melder turns 90: Railwayman and bibliophile extraordinary

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoLOVEABLE BUT LETHAL: When four-legged stars remind us of a silent killer

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoVictor, the Friend of the Foreign Press

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoSeeing is believing – the silent scale behind SriLankan’s ground operation

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoBathiya & Santhush make a strategic bet on Colombo

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoBarking up the wrong tree