Opinion

Leaders’ obsession with global approval hurts ordinary people

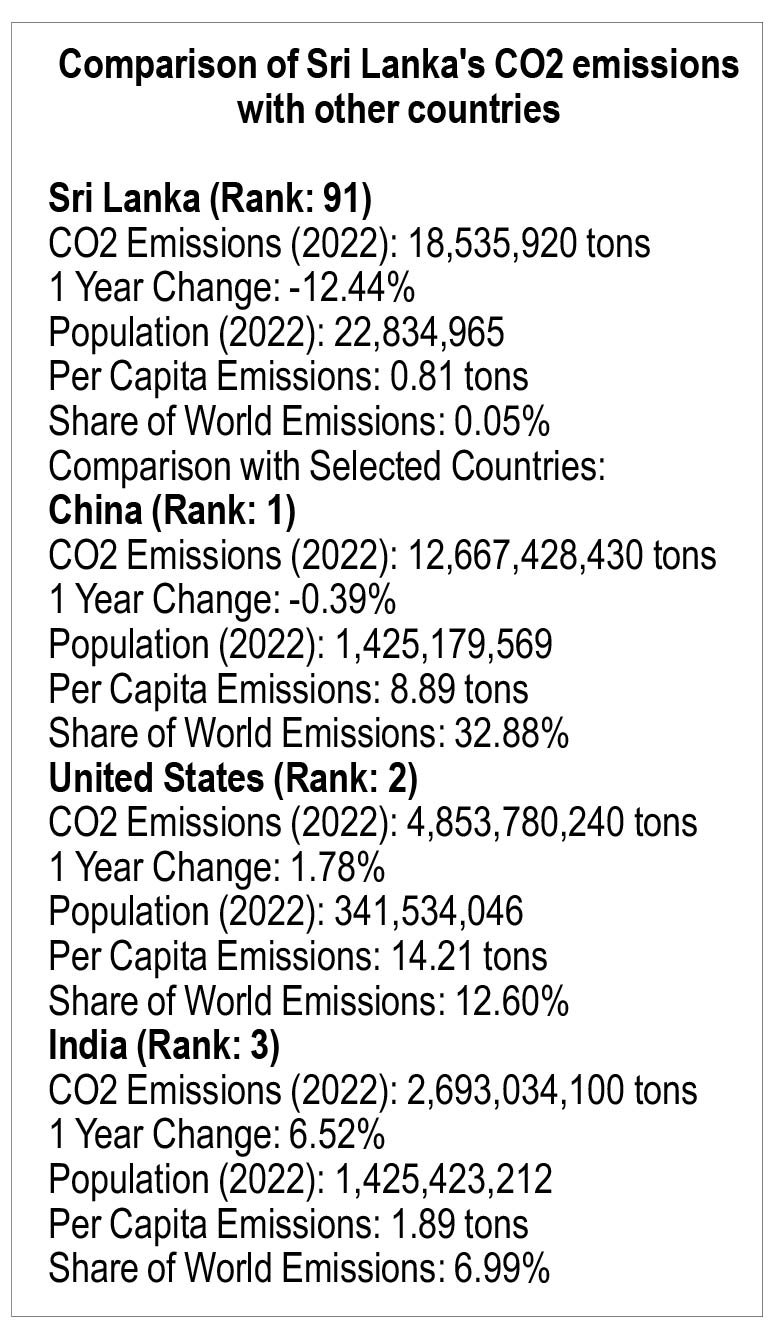

Sri Lanka’s Climate Targets

by Sampath Perera

As Sri Lanka approaches its presidential election, the crucial question for the incoming leader is how to reconcile the country’s economic struggles with the demands of international climate agreements.

With the global climate framework often imposing disproportionate burdens on developing nations, including Sri Lanka, how can the new administration balance ambitious climate goals with the nation’s financial realities? Given Sri Lanka’s modest carbon footprint of 1.02 CO2e tonnes per person, the challenge of achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 seems daunting, especially when many citizens are already grappling with basic economic needs. How will the next leader navigate this complex landscape, ensuring that international commitments are feasible and fair, while also advocating for the unique economic challenges faced by developing countries?

Consider a family of four in Sri Lanka, with a sole breadwinner earning a modest Rs. 50,000 per month. For this family, daily survival is a challenge, let alone the luxury of choosing organic food over cheaper alternatives. The struggle to make ends meet highlights a broader economic reality faced by many Sri Lankan households. Their focus is on affordability and basic sustenance, not on the added expense of organic produce. This scenario encapsulates the difficulty for Sri Lanka in adhering to rigorous climate goals while battling economic hardship.

The next leader must ensure that any international commitments are carefully balanced against the country’s economic capabilities, avoiding undue strain on its already challenged economy. It is essential to advocate for fair terms that recognise the unique struggles of developing nations like Sri Lanka, ensuring that global climate goals are pursued in a manner that is both equitable and achievable.

Unfair burden

In the ongoing global debate over climate action, it is critical to question why world leaders continue to enforce stringent climate goals on developing nations while failing to address the economic disparities that make such goals impractical.

Developing countries, like Sri Lanka, are being pressured to adopt expensive green technologies and reduce carbon emissions, despite their limited economic resources and reliance on cost-effective, traditional energy sources. The insistence on immediate compliance with high-cost climate measures, without providing adequate financial and technological support, places an undue burden on these nations.

This approach not only overlooks their economic vulnerabilities but also ignores the fact that developed countries, which historically have contributed the most to global emissions, continue to rely heavily on fossil fuels. The world’s leading economies should consider shifting their focus towards economic conservation and allowing developing nations the flexibility to pursue more affordable, sustainable solutions. Such an approach would ensure a more equitable transition to a low-carbon future, acknowledging the varied economic capacities and needs of all nations involved.

Sri Lanka’s commitment to achieving net-zero carbon status by 2050, as outlined in its updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), is a noble but daunting task. The country is working towards this goal amidst significant economic pressures, including a recent contraction in GDP and ongoing inflation challenges. The push for a low-carbon economy includes ambitious targets like reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 14.5% by 2030, achieving 70% renewable energy in electricity generation by 2030, and increasing forest cover to 32% by the same year.

Global inequity

Nevertheless, major emitters like China and the United States persistently rely on fossil fuels. China, the world’s largest emitter of CO2, continues to invest heavily in coal power, drawing criticism for its perceived inadequate efforts to cut emissions. Meanwhile, the United States, despite progress in renewable energy, maintains a significant carbon footprint due to its continued dependence on fossil fuels and extensive industrial activities.

These major emitters not only contribute disproportionately to global greenhouse gas emissions but also benefit from relatively less stringent climate regulations compared to those imposed on developing countries. The economic models of China and the US are deeply entrenched in high-carbon industries, and their transition to greener alternatives is often gradual and selectively implemented.

The disparity between the emission targets of developing nations like Sri Lanka and the practices of major emitters highlights a significant global inequity. Developing countries, including Sri Lanka, are often pressured to adopt stringent climate measures while their economies are still emerging. The economic burden of transitioning to a low-carbon economy is substantial, given that these nations are still grappling with basic developmental challenges, such as poverty alleviation and infrastructure development.

Sri Lanka’s climate strategy, including the development of the Carbon Net Zero 2050 Roadmap and Strategic Plan, aims to address key sectors like energy, transport, industry, waste, agriculture, and forestry. However, the implementation of these measures requires substantial financial investment and technological support, which are often lacking in developing contexts.

For Sri Lanka, the challenge lies in balancing the immediate needs of its population with long-term climate goals. The pressure to conform to international climate agreements while ensuring economic stability and growth creates a complex scenario where immediate survival often takes precedence over environmental considerations.

Climate Vs. Economy

Sri Lanka’s development, economic stability, and price fluctuations are heavily influenced by its energy and transport sectors. However, the country’s commitments under international treaties and past pledges by former leaders, often made without fully accounting for Sri Lanka’s economic realities, have placed these crucial sectors under severe strain.

In the energy sector, Sri Lanka faces significant challenges due to its commitment to international climate agreements. The country is bound to achieve a 70% renewable energy target by 2030—a goal that is proving increasingly difficult given the current economic constraints. Traditionally, coal power has been the most cost-effective option for energy generation, but Sri Lanka is restricted from expanding its coal power capacity due to its climate commitments. This restriction places an additional financial burden on the country, making the renewable energy target appear almost unattainable. The Long-Term Generation Expansion Plan (LTGEP) of the Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB) aims to meet this target and maintain a high level of renewable energy beyond 2030, but the financial and logistical challenges are substantial. The government’s push for energy conservation through Demand Side Management could help, but the constraints imposed by international obligations continue to impede progress.

Similarly, the transport sector is critical for Sri Lanka’s economic stability and overall development. It handles 94% of passenger transportation and 98% of freight transportation, making it central to daily life and economic activity. The COVID-19 pandemic caused a significant drop in transport demand, with passenger-kilometers falling from a peak of 231.5 billion in 2019 to 185.5 billion in 2020, partially due to a shift away from public transport. By 2021, demand had only partially recovered to 191.8 billion passenger-kilometers. Public transport’s modal share has decreased from 40.6% in 2019 to 33.0% in 2021.

In such a backdrop, the government’s Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for the automobile industry has further exacerbated issues. Under the SOP introduced by former President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, the assembly of affordable petrol three-wheelers—an essential and low-cost mode of transport for many Sri Lankans—has been banned. This policy, intended to promote electric vehicles, has overlooked the economic realities faced by the general public. Electric solutions are prohibitively expensive for most Sri Lankans, and the absence of three-wheeler assembly has led to the continued use of older, more polluting vehicles. As a result, the lack of affordable, environmentally friendly transportation options has forced many to rely on outdated and inefficient vehicles, further compounding environmental and economic issues.

Sri Lanka’s adherence to international climate commitments has placed undue strain on its energy and transport sectors. The restriction on coal power expansion and the ban on assembling affordable petrol three-wheelers highlight a disconnect between global climate goals and national economic realities.

The country’s journey towards achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 is a testament to its commitment to global climate goals. However, this commitment is challenged by the economic realities faced by its population, exemplified by families struggling to meet basic needs. The contrast between Sri Lanka’s efforts and the continued high-carbon practices of major emitters highlights the need for a more equitable global approach to climate action. To ensure that all nations can contribute to and benefit from a sustainable future, it is essential to address these disparities and provide support where it is most needed.

(The writer is an Attorney-at-Law with an LLM in International Business and Commercial Law. He can be reached at pmwsampathperera@gmail.com.)

Opinion

The Walk for Peace in America a Sri Lankan initiative: A startling truth hidden by govt.

When we come to it

We, this people, on this wayward, floating body

Created on this earth, of this earth

Have the power to fashion for this earth

A climate where every man and every woman

Can live freely without sanctimonious piety

Without crippling fearWhen we come to it

We must confess that we are the possible

We are the miraculous, the true wonder of this world

That is when, and only when

We come to it.

· Concluding lines of the poem ‘A brave and startling truth’

(1995)

– Maya Angelou

Ven. Dr Melpitiye Wimalakitti Nayake Thera, Head Monk of the Wijesundararamaya, Asgiriya, Kandy, and the Chief Incumbent of the Gotama Viharaya Monastery, Fort Worth, Texas, USA, claims that the ongoing Texas to Washington Walk for Peace march led by the American monk of Vietnam origin Ven. Pannakara is ‘an initiative of ours’ (ape wedak). He made this claim during a recent podcast hosted by the well-known YouTuber and journalist Chamuditha Samarawickrema (CNB/February 5, 2026). The Huong Dao Monastery of Bhante Pannakara, who is leading the peace walk is close to the Gotama Viharaya Monastery of Wimalakitti Thera, who tells us that he has had a strong connection with Vietnamese monks and has already collaborated with them in many Buddhist activities.

Talking about Ven. Pannakara, Ven. Wimalakitti says that he is a pupil of senior Vietnamese bhikkhu Ven. Ratanaguna of the same Huong Dao Monastery in Fort Worth Texas. He is leading a team of 24 Buddhist monks from different countries in the (Southeast Asian) region including Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Bangladesh, Laos, etc., taking part in the Walk for Peace (from Fort Worth in Texas to Washington D.C.). It is going to be 2723 miles long according to Wimalakitti Thera. The Walk for Peace started on October 26, 2025 and is due to pass through 4 time zones and 10 states, braving extremes of weather and trekking through patches of harsh terrain.

It was 40 degrees Celsius in Texas, when they started. In seven days, the Peace Walkers reached Georgia in Atlanta. It was raining there. Then, they arrived in South Carolina, where it was cold, the temperature usually being under 20 degrees Celsius. By the time of the podcast with Chamuditha, the Walk for Peace was proceeding through the even colder North Carolina, the temperature barely rising above 1 or 2 degrees Celsius. Then, they reached Virginia with heavy snowfall, but the Walk went ahead nonstop.

The original plan was to walk 8 hours and cover 20 miles in a day. Now they want to do 10 hours a day and cover a targeted 40 miles. They hoped to have at least 20 participants in the Walk at any time. The whole Walk is expected to take 120 days and end on February 13, 2026.

America is a big democratic country, the monk says. The ordinary people are more interested in inner peace than in politics. There are 125 Sri Lankan Buddhist pansalas in America, 15 of which stand on the route of the continuing Walk for Peace. Sri Lankan monks resident in these monasteries, in partnership with monks from other countries, provide the Walkers with essential food, temporary lodgings, and hygienic facilities. They also work out security arrangements for the peace-walking monks in coordination with government and municipal authorities and Police.

Ven. Wimalakitti provides this information as a member and a director of the organising committee responsible for the Walk for Peace project. According to him, Ven. Pannakara takes part in an annual walk in India from Buddha Gaya to Kolkata (the capital city of India’s West Bengal state) as a dhutanga practice (one of the 13 strict ascetic practices recommended for bhikkhus in Theravada Buddhism that aim at perfecting austerity, mental purification, and renunciation). About 200 Buddhist monks join Bhikkhu Pannakara on this walk.

The dog now celebrated as Aloka started following Ven. Pannakara at Buddha Gaya and reached Kolkata with him. He followed the monk even to the airport. Bhikkhu Pannakara could not leave the dog behind in India and fly back to America. So, he canceled his flight and stayed back in India for eight months, during which he trained the dog and completed the paperwork necessary to take him to America with him. Once in America, Aloka sometimes started growling at people at first, because he was not used to the new environment. So, they put a pet cone around his neck to calm him while on the move. Now he participates in the Walk without the pet cone and walks beside Bhikkhu Pannakara at the head of the column of Walkers. The monk usually takes Aloka on a leash and occasionally, off-leash. Aloka had a paw injury during the walk and had to be hospitalised for a few days for surgery. He has rejoined the walk now. The dog has a car reserved for him to move with the walking party whenever he is unable to walk.

Ven. Wimalakitti Thera says he took part in six discussions held at the Huong Dao pansala when the peace walk was being planned. They had to discuss security matters with the Police. Concerns were raised about possible assassination attempts on Bhikkhu Pannakara. The dedicated monk said that he was ready to lay down his life for the cause of the Walk. Wimalakitti Thera said Bhikkhu Pannakara is only 37 years old.

At the beginning of the fourth week into the Walk, there was a serious traffic accident. The monks were walking along the shoulder of the road (near Dayton, Texas, east of Houston, on November 19, 2025) guided by a slow-moving escort vehicle (with hazard lights on). A truck hit the rear of the pilot car pushing it into the monks. The impact left two monks injured, one of them (Phra Ajarn Maha Dam Phommasan, aka Bhante Dam Phommasan) very seriously. The injured monks were airlifted to Houston for medical attention. Bhante Dam Phommasan had to undergo multiple surgeries, including the amputation of his leg. (The information given within parentheses in this piece of writing is added by me for clarity.)

On another occasion (in early January 2026, in Walton County, near Good Hope, Georgia) an unidentified protestor accompanied by a group of his supporters blocked the monks’ path (holding signs like ‘JESUS SAVES’, ‘Turn to Christ’; WARNING: ‘walking to hell’, ‘Hell awaits’, etc., but the people gathered there cheered on the monks, and asked the protestors to just move on). Ven. Wimalakitti (who was presumably on the scene) says that the police diverted them onto an alternative route. The unperturbed monks did not react to the disruptors and continued their walk in silence. The night routes were decided by the Police. The initial hostility petered out gradually, as thousands gathered on the roadsides to watch the monks walking and to listen to the sermons in the night.

(On Christmas Day 2025, the monks stopped at a church in Alabama, before entering into Georgia the next day.) Ven. Wimalakitti says that when Bhikkhu Pannakara made an address in the church that evening, it was filled to capacity, and his speech had to be broadcast on outdoor screens.

The Walk actually began as a dhutanga (please, see above) observance as Ven. Wimalakitti explains during the discursive podcast, which forms the basis of this essay. But, on the third day, the name was changed to ‘Walk for Peace’. Its purpose is non-religious and non-political. ‘Today is my day of peace’ is the theme. (Ven. Pannakara exhorts) “When you get up in the morning, say to yourself ‘Today is going to be my day of peace’”. When Wimalakitti Thera says “Ordinary Americans are really interested in Meditation (bhavana). They are much less interested in the dhamma”, he is making an obvious oversimplification that seems to be limited exclusively to the current Walk for Peace context.

WimalakittiThera claims that a single Pakistani individual from Texas ‘provides security for the Walk’. However much I tried, I couldn’t catch his name as the monk pronounced it. So I sought AI help. AI clarifies that ‘Based on the results of the 2025-2026 Walk for Peace from Texas to Washington D.C., the security and the logistics for the Buddhist monks are primarily handled by local law enforcement agencies (sheriffs and police departments) who secure the roads as the group walks’.(So, there is no mention of a Pakistani (American) providing security for the walk). The monk might be mistaken about the matter. But that piece of information is not so important. Though the monks have absolutely no political motives, the Sri Lankan monk thinks they expect (US President Donald) Trump to be there when they reach Washington, near the White House. A reception for the monks is scheduled to take place on that occasion with the participation of the Sri Lankan ambassador.

The highlight of the Chamuditha News Brief (CNB) podcast featuring Ven. Dr Melpitiye Wimalakitti uploaded on February 5, 2026 is his revelation of a well-kept secret, which is that the Sri Lankan monks living in America played the major pioneering role in organising the Walk for Peace across America project and that they wanted the Sri Lankan government to support it. The 17-member organising committee under the leadership of Ven. Wimalakitti, including the Vietnamese American bhikkhu Ven. Pannakara (who is now leading the Walk for Peace march) visited Sri Lanka in this connection in May 2025, that is, nine months ago. Ven. Wimalakitti showed the group photographs that the visiting monks took with prime minister Harini Amarasuriya, some ministers and other dignitaries. Still, ordinary Sri Lankans are unaware of this momentous event, it seems.

Unfortunately, there had not been any response to the monks’ request up to the day that Chamuditha did the podcast with Ven. Wimalakitti. The monk said that he broke off his participation in the Walk in order to visit Sri Lanka again for the express purpose of urging the Sri Lankan government’s participation in the Vesak celebration at Walk team leader Ven. Pannakara’s monastery in Texas in May. Ven. Wimalakitti said he gave the president and the prime minister (as I think he claimed) formal invitation cards requesting them to arrange for government delegates to attend the Vesak ceremony set to be held at the Huong Dao Monastery of Ven. Bhante Pannakara in Dallas, Fort Worth, Texas on May 26 this year (2026). He also wants them to grace the transport of relics from Sri Lanka. The monk was due to leave for America the night following the day of the programme with Chamuditha; but he had still got no reply from those important invitees. However,the Sri Lankan Ambassador in Washington is taking a great interest in this event, according to Ven. Wimalakitti.

At the end of the podcast, Ven. Wimalakitti voiced two important messages: “I want to say a word of diplomatic importance. This is a great opportunity for Sri Lanka, diplomatically speaking. This is a moment of awakening, not only for America but also for the whole world. All of you citizens of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka as a Theravada Buddhist state, can make your contribution to this global awakening. I urgently request that this great opportunity be not missed”. (The Walk for Peace, the peace pilgrimage across America, from Texas to Washington D.C., is performed by a group of Theravada Buddhist monks. It showcases the key Buddhist spiritual values of compassion, loving-kindness, non-violence, and peace that underlie Sri Lanka’s dominant religious culture. These values are a source of soft power for Sri Lanka in its diplomatic and cultural relations with the powerful United States of America.)

“Secondly, as Buddhists of Sri Lanka, please don’t criticise our monks or the Buddhist religion, simply because others do so. Please, think about this (insulting the monks and the Dhamma) with great equanimity. Both Buddhist monks and laypersons must keep updated about current trends. Some of our monks often attract criticism because they fail to adjust to changing times.”

By Rohana R. Wasala

Opinion

Beyond 4–5% recovery: Why Sri Lanka needs a real growth strategy

The Central Bank Governor’s recent remarks projecting 4–5 percent growth in 2026 and highlighting improving reserves, lower inflation, and financial stability have been widely welcomed. After the trauma of Sri Lanka’s economic crisis, any sign of normalcy is understandably reassuring. Yet, this optimism needs to be read carefully. What is being presented is largely a story of stabilisation and recovery, framed in the familiar IMF language of macroeconomic management. That is necessary, but it is not the same as a pathway to durable growth.

The first issue is the nature of the projected growth itself. A 4–5 percent expansion can occur for many reasons, not all of which strengthen an economy in the long run. In this case, a significant part of the momentum is expected to come from post-cyclone reconstruction and public investment. This will boost activity in construction and related services and create jobs in the short term. But such growth is typically demand-led and temporary. It raises GDP without necessarily expanding the country’s productive capacity, technological capability, or export competitiveness. Once the reconstruction cycle fades, so may the growth.

This points to a crucial distinction that often gets blurred in public debate: economic recovery and durable growth are not the same thing. Recovery means returning to a more normal macro environment—lower inflation, a more stable exchange rate, some rebuilding of reserves, and a functioning financial system. Durable growth, by contrast, requires rising productivity, structural change, and a stronger export base. Sri Lanka can achieve the first without securing the second. Indeed, that is precisely what happened in earlier post-crisis episodes, where short-lived recoveries were followed by renewed external stress.

The Central Governor’s narrative is best understood as an IMF-style stabilisation narrative. Its centre of gravity is macro control: inflation targets, policy rates, reserves, debt service, and financial-sector resilience. These are the right tools for preventing another crisis. But they are not a strategy for accelerating development. IMF programmes are designed primarily to restore confidence, manage risk, and stabilise the macroeconomy. They are not designed to answer the core development questions: What will Sri Lanka produce? What will it export? How will productivity rise? Which sectors will drive long-term growth?

Seen in this light, a projected 4–5 per cent growth rate is best described as moderate recovery growth. It may be entirely plausible—especially if driven by reconstruction and public spending—but it is not the kind of growth that closes income gaps, absorbs underemployment at scale, creates sustained fiscal space, or materially reduces debt burdens. Countries that have successfully caught up in Asia typically sustained 7–8 per cent (or higher) growth for long periods, powered by export expansion, industrial upgrading, and continuous learning.

If the current government’s development agenda is genuinely ambitious, then there is a clear mismatch between the growth implied by that ambition and the growth described in the Central Bank’s outlook. A strategy that settles for 4–5 per cent risks normalising mediocrity rather than mobilising the economy for take-off. Reconstruction-led and consumption-led expansions can lift GDP in the short run, but they do not, by themselves, deliver the productivity and export breakthroughs needed for sustained 7–8 per cent growth.

There is also a risk that reconstruction-driven growth will recreate old external vulnerabilities. Large-scale rebuilding increases demand for cement, steel, fuel, machinery, and transport services—many of which are import-intensive in Sri Lanka. This means higher growth can go hand in hand with a widening trade deficit, renewed pressure on foreign exchange, and imported inflation. The Governor has rightly warned about inflationary and external pressures, but the deeper issue is structural: without a parallel expansion of export capacity and domestic production of tradables, stimulus-driven growth can quickly collide with the same constraints that caused past crises.

The improvement in reserves and the claim that debt service is “manageable” are positive developments. But they should be treated as buffers, not proof of long-term security. Sri Lanka’s recent history shows how quickly reserves can be run down when imports surge, exports disappoint, or global conditions tighten. Reserves buy time. They do not, by themselves, change the underlying growth model.

Similarly, the focus on bringing inflation back towards target and maintaining steady policy rates reflects sound central banking. Price stability and financial-sector resilience are public goods. But an inflation target is not a growth strategy. Durable growth comes from investment in productive capacity, from learning and technological upgrading, from moving into higher-value activities, and from building competitive export sectors. Without these, macro stability becomes an exercise in maintenance rather than transformation.

The repeated reference to “structural reforms” also needs to be treated with care. In policy practice, this often means reforms to pricing, state-owned enterprises, taxation, and public finance management. These may improve efficiency and governance, and they matter. But in development economics, structural transformation means something more demanding: a change in what the country produces, how it produces, and what it sells to the world. It means shifting resources into higher-productivity, more technologically advanced, and more export-oriented activities. Without that shift, an economy can be well-managed and still remain fragile.

What is striking in the Governor’s statement is not that it is wrong, but that it is incomplete. We hear a great deal about stability, recovery, and resilience. We hear much less about the growth strategy itself. Which sectors are expected to lead the next phase of growth beyond construction and consumption? How will exports be diversified and upgraded? What is the plan for skills, technology, and productivity? How will private investment be steered toward tradable, foreign-exchange-earning activities?

These are not academic questions. They go to the heart of whether Sri Lanka is merely staging another rebound or beginning a genuine breakthrough. The country’s repeated crises have shown that returning to “normal” is not enough if the underlying growth model remains unchanged.

In sum, the Central Bank Governor’s optimism should be understood for what it is: a stabilisation narrative, not yet a development strategy. It tells us that the economy is becoming calmer, more predictable, and less crisis-prone—and that is a real and necessary achievement. But it does not yet tell us how Sri Lanka will grow fast enough, long enough, and differently enough to escape its long-standing cycle of weak exports, external vulnerability, and stop–go growth.

A recovery built on reconstruction, consumption, and macro control can deliver 4–5 per cent growth. But the government’s own ambitions—and Sri Lanka’s development needs—require 7–8 per cent sustained growth driven by productivity, exports, and structural transformation. That kind of growth does not emerge automatically from stability. It must be designed, coordinated, and pursued through a clear strategy for production, learning, and upgrading.

Stability is essential. Without it, nothing else is possible. But stability is not a development strategy. It is the foundation on which a strategy must be built. The real test for policymakers now is not whether they can keep the economy stable, but whether they can articulate and implement a credible growth strategy that turns stability into momentum and recovery into transformation. Until that strategy is clearly on the table, Sri Lanka’s current optimism—welcome as it is—should be read with caution, not complacency.

by Prof. Ranjith Bandara

Opinion

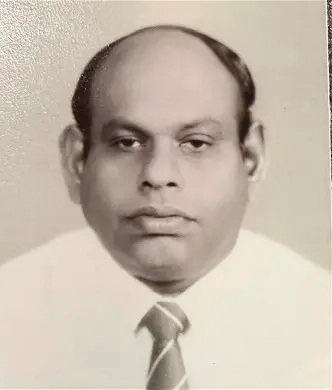

V. Shanmuganyagam (1940-2026): First Clas Engineer, First Class Teacher

Quiet flows another don. The aging fraternity of Peradeniya Engineering alumni has lost another one of its beloved teachers. V. Shanmuganayagam, an exceptionally affable and popular lecturer for nearly two decades at the Peradeniya Engineering Faculty, passed away on 15 January 2026, in Markham, Toronto, Canada. Shan, as he was universally known, graduated with First Class Honours in Civil Engineering, in 1962, when the Faculty was located in Colombo. He taught at Peradeniya from 1967 to 1984, and later at the Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, before retiring to live in Canada.

In October last year, one of our colleagues, Engineer P. Balasundram, organized a lunch in Toronto to felicitate Shan. It was very well attended and Shan was in good spirits. At 85 he was looking as young as any of us, except for using a wheelchair to facilitate his movement. The gathering was remarkable for the outpouring of warmth and gratitude by nearly 40 or 50 Engineers, who had graduated in the early 1970s and now in their own seventies. One by one every one who was there spoke and thanked Shan for making a difference in their lives as a teacher and a mentor, not only in their professional lives but by extension in their personal lives as well.

As we were leaving the luncheon gathering there were suggestions to have more such events and to have Shan with us for more reminiscing. That was not to be. Within three months, a sudden turn for the worse in his condition proved to be irreversible. He passed away peacefully, far away across the world from the little corner of little Sri Lanka where he was born and raised, and raised in a manner to make a mark in his life and to make a difference in the lives of others who were his family, friends and several hundreds of engineering professionals whom he taught.

V. Shanmuganayagam was born on May 30, 1940, in Point Pedro, to Culanthavel and Sellam Venayagampillai. His family touchingly noted in the obituary that he was raised in humble beginnings, but more consequentially his values were cast in the finest of moulds. He studied at Hartley College, Point Pedro, and was one of the four outstanding Hartleyites to study engineering, get their first class and join the academia. Shan was preceded by Prof. A. Thurairajah, easily Sri Lanka’s most gifted academic engineering mind, and was followed by David Guanaratnam and A.S. Rajendra. All of them did Civil Engineering, and years later Hartley would send a new pair of outstanding students, M. Sritharan and K. Ramathas who would go on to become highly accomplished Electrical Engineers.

Shan graduated in 1962 with First Class Honours and may have been one of a very few if not the only first class that year. Shan worked for a short while at the Ceylon Electricity Board before proceeding to Cambridge for postgraduate studies specializing in Structures. His dissertation on the Ultimate Strength of Encased Beams is listed in the publications of the Cambridge Structures Group. He returned to his job at CEB and then joined the Faculty in 1967. At that time, Shan may have been one of the more senior lecturers in Structures after Milton Amaratunga who too passed away late last year in Southampton, England.

When we were students in the early 1970s, there was an academic debate at the Faculty as to whether a university or specific faculties should give greater priority to teaching or research. Shan was on the side of teaching and he was quite open about it in his classes. He would supplement his lectures with cyclostyled sheets of notes and the students naturally loved it. It was also a time when Shan and many of his colleagues were young bachelors at Peradeniya, and their lives as academic bachelors have been delightfully recounted in a number of online circulations.

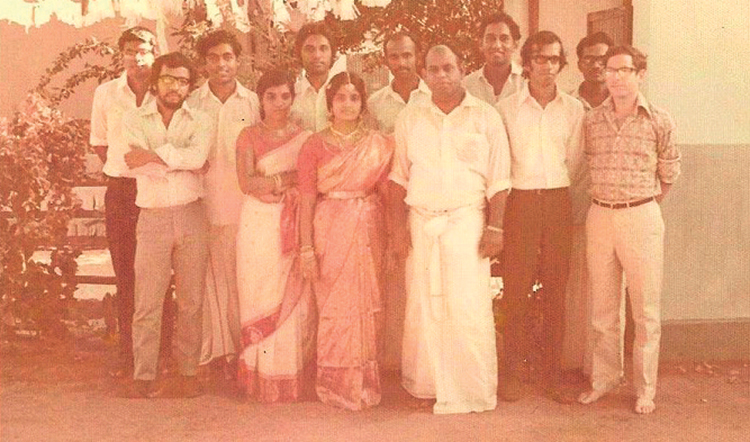

The cross-sectional camaraderie at the Faculty in those days is well captured in one of the photographs taken at Shan’s wedding at Point Pedro, in 1974, which too has been doing the rounds and which I have inserted above. Flanking Shan and his bride Kalamathy, from Left to Right are, M. Dhanendran, Nandana Rambukwella, K. Jeyapalan, Wickrama Bahu Karunaratne, A.S. Rajendra, Lal Tennekoon, Tusit Weerasooria, and R. Srikantha. Sadly, Rambukwella, Karunaratne (Bahu), Tennekoon and now Shan himself, are no longer with us.

Like other faculty members, Shan kept contact with his former students turned practising engineers and they would reach out to him to solicit his expertise in their projects. In the early 1980s, when I was working as Resident Project Manager with my Peradeniya contemporaries, JM Samoon and K. Balasundram, at the Hanthana Housing Scheme undertaken by the National Development Housing Authority (NHDA), Shan was one of the project consultants helping us with concrete technology involving mix design and in situ strength testing using the testing facilities at the Faculty.

The Hanthana Team Looking back, the Hanthana housing scheme construction was the engineering externalization of the architectural imaginings of Tanya Iousova and Suren Wickremesinghe, for building houses on hill slopes without flattening the hills. The project involved the construction of hundreds of housing units with supporting infrastructure comprising roads and drainage, water supply and sanitary, and electricity distribution using underground cables. Tanya & Suren Wickremasinghe were the Architects with an Italian construction company as contractors.

To their credit, Tanya and Suren assembled quite a team of Consulting Engineers that was a cross-section of E’Fac alumni, viz., Siripala Kodikkara and Siripala Jayasinghe (Contract Administration); Prof. Thurairajah (Foundations & Soil Mechanics); S.A. Karunaratne (Structures); V. Shanmuganyagam (Concrete Technology); Neville Kottagama and DLO Mendis (Roads & Drainage); K. Suntharalingam (Water Supply & Sanitary); and Chris Ratnayake (Electrical).

As esoteric gossip goes, DLO Mendis had an informal periodization of engineering graduates, identifying them as either Before-Thurai or After-Thurai, centered on 1957 – the year Prof. Thurairajah graduated with supreme distinction and went on to do groundbreaking theoretical research in Soil Mechanics at Cambridge. Of the Hanthana consultant team, Neville Kottagama and DLO Mendis were before Thurai by six years, Shan was five years after, and all the others came later. Sadly though, only Tanya and Chris are with us today from the 1980s group named above.

After Hanthana came 1983 when all hell broke loose and hundreds of professionals and their families were forced to leave Sri Lanka. Shan left Peradeniya and joined Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, encouraged by his Cambridge contemporaries from Singapore. He taught at Nanyang for twelve years (1984-1996) before moving to Canada with his wife and three sons who were by then ready for university education.

All three children have done exceptionally well in their studies and professional careers. The oldest, Dhanansayan, is a Medical Doctor and a Professor at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, in Madison, United States. That was where India’s Jayaprakash Narayan and Sri Lanka’s Philip Gunawardena had their university education a hundred years ago.

The younger two sons took to Engineering. The second son, Kalaichelvan, is Program Manager at Creation Technologies, an award-winning global electronics manufacturing service provider. And the youngest, Dhaksayan, is the Chief Information Officer (CIO) at the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC), which is North America’s third-largest urban transit system.

All three have done their parents proud and Shan would have been gratified to see them achieve exemplary success in their chosen fields. A first class Engineer and a first class teacher, Shan was also a great father and a loving grandfather. As we remember Professor Shanmuganyagam, we extend our thoughts and sympathies to his beloved wife Kalamathy, his sons and their young families

by Rajan Philips

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoMy experience in turning around the Merchant Bank of Sri Lanka (MBSL) – Episode 3

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoZone24x7 enters 2026 with strong momentum, reinforcing its role as an enterprise AI and automation partner

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoRemotely conducted Business Forum in Paris attracts reputed French companies

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoFour runs, a thousand dreams: How a small-town school bowled its way into the record books

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoComBank and Hayleys Mobility redefine sustainable mobility with flexible leasing solutions

-

Business23 hours ago

Business23 hours agoAutodoc 360 relocates to reinforce commitment to premium auto care

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoHNB recognized among Top 10 Best Employers of 2025 at the EFC National Best Employer Awards

-

Editorial7 days ago

Editorial7 days agoAll’s not well that ends well?