Features

Kohomba Kankariya, the sociology of a Kandyan ritual

Kohomba kankariya, the sociology of a Kandyan ritual,

by Sarath Amunugama

(Yapa Publications, Colombo, 2021).

Reviewed by Usvatte-aratchi

‘What we have described in this book are the halcyon days of Kandyan dancing….. ’ Amunugama.

Sarath Amunugama has put out a new book and it is on the Kohomba Kankariya. This is the first book on the subject that I read, although there are three others in Sinhala in my collection. Two of them are collections of kavi and other statements in the ritual. None of them describes the performance of a kankariya in detail, as Amunugama does.

Of them, the book that comes close to Amunugama’s concerns is that by Mudiyanse Dissanayaka, an accomplished artist and teacher (one time professor at the University of the Visual Arts in Colombo) of dancing. Dissanayake in the last chapter of his book deals with some concerns relevant to Amunugama’s subject matter: the sociology of the ritual. Amunugama’s Kohomba Kankariya is the first full length treatment of the subject. That is in contrast to the extensive attention paid to healing rituals in the southern coastal belt, by scholars, both local and foreign.

I am personally familiar with actual performances of sooniyama, sanni yakuma and rata yakuma, having seen them when I was a child and never forgot. I have never seen a kohomba kankariya live or on record. Amunugama writes a fine account of a kankariya which was performed in Rangamuwa, in 2015 in a village near his parents’ home. He himself was the prime mover organizing it. He also noted the distinction that other forms of dancing (panther, udakki, raban) in and around Kandy and were undertaken by high caste persons. After all he is ‘Kandy Man’. That itself makes reviewing this book difficult. It is partly personal and mostly professional. I shall try, nevertheless.

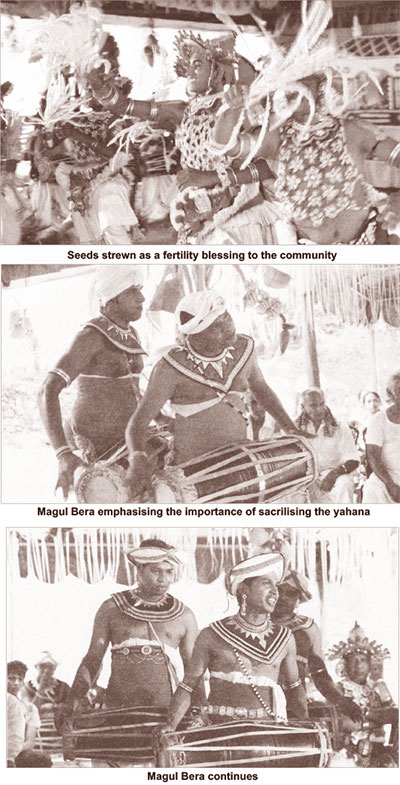

The book consists of three essays: the first sets before us, in exquisite detail, the performance of the ritual in Rangamuwa. While doing so, he explains to us the sociology of what goes on. The second essay on ves natum is an extraordinary foray into the emergence of scenes from rituals to the mainstream entertainment in Colombo: ‘….traditional culture….., shifting emphasis from ritual to commerce’. That shift was preceded by Kandyan dancing being introduced to western audiences, not as art but as acrobatics. The persons who brokered this transfer were a most unexpected lot. The third, the shortest is a collection of photographs, some in colour, of personages connected with the Rangamuva kohomba kankariya and other earlier celebrated dancers.

The book consists of three essays: the first sets before us, in exquisite detail, the performance of the ritual in Rangamuwa. While doing so, he explains to us the sociology of what goes on. The second essay on ves natum is an extraordinary foray into the emergence of scenes from rituals to the mainstream entertainment in Colombo: ‘….traditional culture….., shifting emphasis from ritual to commerce’. That shift was preceded by Kandyan dancing being introduced to western audiences, not as art but as acrobatics. The persons who brokered this transfer were a most unexpected lot. The third, the shortest is a collection of photographs, some in colour, of personages connected with the Rangamuva kohomba kankariya and other earlier celebrated dancers.

The reader would enjoy the systematic presentation of the kankariya. Here, I will offer a few comments on the sociology of it, well aware that I, no sociologist, dare to comment on the writings of a most brilliant student of the subject in the country. Amunugama has an ambitious plan in this essay: ‘ …. what I am attempting here is to prepare a schematic ‘frame’ into which all or most rituals can be incorporated. …….all local healing rituals have the same basic format…’. While the schemata that Amunugama presents is mostly complete, he misses a very substantial part of the of suniyama.

For several hours in the early hours of the following morning, yakdessa conduct various acts to remove all evil influences afflicting the aturaya. These include puhul kapima (cutting a cucumber), cutting tholabo (a kind of yam), dehi (lime) kapima, valalu kapima (the patient is put in a sort of cage made of cane and the cane is cut to set him/her free), symbolically removing all that afflicts him. Sirasa pada kavi comes in here. Finally, the whole atamagale, made of banana tree skins and gokkola (young coconut fronds’) in which the aturaya sat all night, is cut down. All this is furious activity with several yaddessa wielding knives is entirely exciting. It may be useful to consider that. Amunugama successfully analyses the kankariya in terms of this schemata.

I found the second essay the most engaging. Its subtitle is ‘from cosmic drama to street and stage spectacle’ announces to us the processes he analyses. The personages who facilitated that transfer of whom Amunugama writes are of equal interest, because those personages and dancers belonged in different worlds. But yesterday, ves natum was in kohomba kankariya in villages in kande uda rata. Today, corona permitting, we sit in the comfort of the balcony of the Queen’s Hotel and watch ves netum and sit in the Lionel Wendt and watch Chitrasena’s ‘karadiya’ or Ravi Bandhu lead a drum ensemble. Ves dancers play before potentates in Colombo or conduct a bride and bridegroom to the poruva in Guruva pattu far distant from Harispattu. How did that shift take place? What social forces enabled that change? Who were the agents who activated the process? Those are questions to which Amunugama provides answers, probably never final.

The kankariya and ves netum were performed by men of the berava caste, low in esteem in the hierarchy. Like almost all ritual healers among the Sinhala, these ritualists tilled some land from which they derived a meager income, which they supplemented from performing rituals. To dance before Europeans, to dance before royalty (Edward, the Prince of Wales) and before the Governor were some sort of manumission. When they travelled to Europe and US in late 19th century, and early 20th century as performers in circuses they not only earned some money but also stood in altered relations to their foreign employers.

For the Europeans, these dancers were exotic people from strange lands. From the beginning of the 16th century, when the Portuguese ventured south along the eastern coast of Africa, never far beyond to lose sight of land and went inland along Sierra Leone rivers they came across people quite unlike themselves and with manners and customs utterly foreign to them. The sailors came home and spoke of those wonders and exaggerated the unusual features so much so that there were stories of men from whose head trees grew. Gulliver’s Travels is an outcome from these fanciful stories.

Kings kept zoos of animals from tropical lands and humans who were different from themselves. Vimala Dharma Suriya I, when he became king in maha nuvara repeated this experience which he had witnessed in Lisbon. In 1917, P.B. Nugawela, a high caste potentate brought ves natum to the dalada perahera. Writes Amunugama, ‘…..the yakdessas…. had to be brought in as Sinhala society began to emerge from its feudal straitjacket’. The Ceylon National Congress, a political organization looking for identifying itself with national culture began to espouse Kandyan dancing.

In the 1930s, Western educated aesthetes in Colombo, the 43 Group led by George Keyt, ‘discovered’ these dancers and dances. Their photographs were published in Europe. The dancers appeared in exhibitions in Europe. The dancers ‘….(moved) away from the Kankariya to enter the global stage as dance performers and drummers’. ‘Nittawela Gunaya, the finest exponent of the Kandyan dance on stage…. was not interested in the Kankariya ritual’. The same could be said of Sri Jayana. Those processes need further analysis.

A high official in the department of education in the late 1930s, S.L.B Sapukotana, was enthusiastic about teaching Kandyan dancing in all schools. Such change would have given a new social status to members of the berava caste and of course raised their incomes. In 1947 or so, Mr. Punchi Banda arrived in the then remote little town Hikkaduva, where I was a student, to teach Kandyan dancing. And we learnt the first steps ‘thei, thei’ and a few days later ‘thei kita, kita thei ‘. We first danced the musaladi (Tamil for a hare) vannama. That process has gone on and now many children in most schools learn Kandyan dancing.

The clothing of ritualists in the coastal belt have changed, influenced by the costumes of Kandyan dancers. The all white cloth from the waist to the ankles that ritualists in the south wore now has red and blue lines at the ankles. Drummers who sometimes tied a white piece of cloth round their heads now wear an elaborate headdress copying dancers in the Kandyan tradition. Many cultural practices from the hills have been adopted by those in the plains, e.g. wedding suits have changed from European to thuppotti. Brides now mostly commonly adorn themselves with Kandyan sari and matching jewellery. These phenomena, someone needs to inquire into.

The most striking transfer of rituals to the proscenium theatre was brought about by Ediriweera Sarachchandra, when he wrote and directed Maname nadagama. The story was from the jataka potha. It was a village ritual, more entertainment, that was played over seven evenings on a village heath. Sarachchandra brought it on stage as a sophisticated play that lasted a mere two hours. He went to the same well, the jataka pota, for fresh themes and we had kada valalu (in which Amunugama acted), pemato jayato soko, loma hansa while hasti kanta mantare was from the dhammapadattha kata. This well seems to have been beyond the depths of those that came after Sarachchandra. These are subjects for broader and deeper inquiry.

In the last essay Amunugama presents a series of ‘….photographs of the kankariya and its associated personnel’. Here and elsewhere in the book, there are photographs of dancers like Gunaya, Suramba, his two sons Sumanaweera and Samaraweera and Chitrasena. There are also pictures of Lionel Wendt and George Keyt.

I conclude.

Diversion to Pali grammar.

On page 18, Amunugama presents a stanza which he says, ‘identifies the hopes and prayers of Sinhala Buddhists’. In homes of many people in this country, this stanza is heard, often several times a day.

devo vassatu kaalena- sassa sampatti hetu ca

pito bhavatu loko ca- raja bhavatu dhammiko.

He translated it as follows: ‘may Gods bring rain in due season- cause our livelihoods to prosper/may the populace be happy and may the ruler be righteous’. I have seen the same stanza, as presented here, in a number of places. As I found its grammar intriguing, I inquired where it was copied from. I learnt that it came from H.W.Codrington’s, A short History of Ceylon, published in 1926.

There are several problems with both copying the stanza and its translation. All the verbs are in the benedictive mood, singular number: vassatu (pl.vassantu), hotu (pl.hontu) and bhavatu (pl.bhavantu) The verb in the second line is hotu not hetu. The benedictive verb in Pali has this ‘tu’ ending. Then, devo vassatu kalena is singular and the subject cannot be in the plural: Gods. The fact is that devo, is rain or water (devo vassati is the Pali equivalent of ‘It rains’. Rhys Davids, Pali Dictionary). Then devo vassatu kaalena says ‘may it rain in season’. In the second line, the words hetu ca was copied for Codrington, wrong. There is a word hetu as in ‘ye dhamma hetuppabhava’, attributed to Sariputta. ‘hetu’ here means cause (noun). In contrast, hotu means ‘may there be’, the benedictive form of hoti (plural: honti, to be). So all three verbs are in the benedictive mood: vassatu, hotu and bhavatu. tu ending also occurs in another usage. ‘aham gaccatu kamo.’ (I like to go); or ‘bilalo musike khadatu kamo (a cat likes to eat mice’). Ca is a common conjunction equivalent to ‘and’. The translation of the line is, ‘may crops (literally, cereals) be plentiful’. There are no problems with the last two lines, except perhaps to note that raja is singular, (plural rajano, an irregular declension.) Now even bhikkhu (bhikkhu is the plural as well) have no intelligent reading of Pali, as we hear day in day out on television. To lose a language is to suffer a tremendous loss.

Features

True Santa & Fake Santa in the US. NPP underwhelmed by Square-toed Critics

A telling Christmas cartoon in a Canadian newspaper (The Globe and Mail) shows the American Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents apprehending and attacking Santa Claus as he lands in the US presumably without a visa. For their part, ICE agents have gone a step worse and got one of their men to be a fake Santa, with an ICE logo, in an advertisement that promises US immigrants a payment of $3,000 and free flight ‘home’ for Christmas if they would voluntarily turn themselves in. The overexcited and out-of-depth Department of Homeland Secretary Kristi Noam has added her two cents: “Illegal aliens should take advantage of this gift and self-deport.”

That is Trump’s America and it is at terrible odds with the historical image of America that the first American Pope in Vatican devoutly cherishes and is unabashedly defending. Paraphrasing the gospel of Matthew, the Pope had pointedly admonished, “Jesus says very clearly, at the end of the world, we’re going to be asked, ‘How did you receive the foreigner?” The American Bishops followed suit and in a rare rebuke of the Administration, have expressed their “concern for the evolving situation impacting immigrants in the United States”.

But not all American Catholics are with the Pope and their Bishops. Sixty percent of white American Catholics are said to be in favour of Trump’s vicious crackdown on immigrants. They and their voluble intelligentsia are a bulwark of Trump’s MAGA (Make America Great Again) bandwagon. Five of the nine Supreme Court judges are conservative white Catholics. They are aided and abetted by Clarence Thomas, the lone male African-American and conservative judge on the bench. The six judges, ignoring the dissenting liberal judges, have been giving judicial cover to practically all of Trump’s controversial second term initiatives.

The new bullhorn foreign policy towards Europe is the speciality of Vice President JD Vance, a late convert to Catholicism and married to a Hindu Indo-American. The oversight of Central and South America is the responsibility America’s new neocons, the Cuban neocons, led by Secretary of State Marco Rubio, a Catholic Cuban American with a ton of chips on his shoulders. Trump used to deride him as “little Marco.” Marco Rubio wants the US to browbeat Venezuela and use it as an example to other Latin American countries.

But Trump’s support is falling and almost all of his new initiatives are beginning to unravel even before he has finished the first year of his second term. Even among Catholics who are 20% of the population numbering 50 million, the 60% support of white American Catholics is negated by the opposition of 70% Hispanics to Trump’s deportation program even though Trump made significant inroad among Hispanics in the 2024 election. Among all Americans Trump has a negative approval rating with nearly 60% of Americans dissatisfied with his policies and performance across the board.

At 79, Trump is beginning to walk and talk like Biden when the latter was in office as the oldest American President. Trump is not losing his grip on power but he cannot keep tab on his zealous acolytes as they rush to further their own agendas on immigration, controlling Latin America and jettisoning Europe. It is the economy that is his business. It is literally so insofar as his family is enabled to make as much hay as they can before the curtain crashes. And the country’s economy will be his Achilles Heel just as it was for Biden. Trump will be considerably deflated should the Supreme Court rule against him on the constitutionality of his idiosyncratic tariff scheme. On the other hand, if the Court’s conservative judges were to rule in his favour it will do lasting damage to their already tattered credibility.

Regardless, the Trump presidency is not going to end all of a sudden like in so many other countries including Sri Lanka in 2022. The built in inertia of the US system will provide for the Trump presidency to peter out and for the country to take an even longer time to be rid of the damages he has done to the institutions and to restore them slowly. In the meantime, one would hope that the carnage in Ukraine will be soon brought to an end. And, as Pope Leo XIV said in his Christmas homily, the people “in the tents in Gaza, exposed for weeks to rain, wind and cold, ” should be soon helped out of the “rubble and open wounds.”

While it is too soon to speculate about post-Trump America, Trump’s impact on the American political system over the last 10 (to be 15) years in politics is obvious. First, he was able to instigate a critical mass of people into believing that the mainstream political discourse is a fake enterprise. That was his route to victory in 2016 and much of his first term was about consolidating the belief of his followers that everyone who was opposing him were fake and un-American. He took the next step and made them believe that the 2020 presidential election was stolen from him by the political establishment and was given to Joe Biden. The Trump’s playbook is being adapted by like-minded leaders in other countries to score their own political victories. Accusations of fake news, allegations of stolen elections, and widespread disinformation – i.e. intentionally spreading incorrect information – have now become the stock of politics in a number of countries. Sri Lanka is not one of them but it does manifest symptoms of this new malaise.

The NPP and its Square-toed Critics

Allegations of election fraud have always been a fact of political life Sri Lanka. A sizeable forensic industry grew out of petitioning courts to challenge the results of individual constituency elections based on allegations of fraud and corruption. The two old Left Parties would have none of it and would accept the results of the election based on the official counts. They never challenged the results of any election that was lost by any of its candidates. When the Left was shut out of parliament in 1977, NM Perera wrote for the LSSP that the Party had been shut of the legislature twice in its history. First, from the State Council by colonial Order in Council, and in 1977 by the people themselves. It fought the colonial expulsion but accepted the verdict of the people.

Allegations of foreign interference are also not new. The Left had its routine rhetorical flights to warn of the circumambient presence of imperialism. The UNP countered with homemade stories of Chinese spies. But the first serious questioning of an election result and the accusation of foreign interference came after the 2015 presidential election that saw the defeat of Mahinda Rajapaksa when he tried to win an illegitimate third term in office. It was also the first defeat of a sitting president. The first reaction was to blame Tamil treachery. The second was to blame the long hand from New Delhi. Neither took serious traction but they created a local genre of political punditry that keeps itself busy.

The Rajapaksas have grown out of it. Their elders have no time for it and their next generation is desperate about finding a future foothold. But their loyal pundits keep churning. The latest addition to this genre of commentary is the finally revealed revelation about the supposedly sensational proposition made by former Indian High Commissioner Gopal Baglay to former Speaker Mahinda Yapa Abeywardena, on the morning of that fatefully eventful day of 13 July 2022, that Mr. Abeywardena should immediately become Sri Lanka’s new President.

Obviously, this meeting would have taken place after Gotabaya Rajapaksa had fled the country in the wee hours of that same morning. But what is not clear is whether GR’s letter of resignation was already official and whether GR’s appointment of Ranil Wickremesinghe as Acting President had already come into effect. Mr. Wickremesinghe himself has revealed the circumstances of his taking oath as president after GR’s fleeing – that the oath was taken in secrecy in a Colombo Temple – in an interview with former Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper, after a meeting of the International Democracy Union (IDU) in London. The UNP is an IDU member and Harper its Chairman.

There is no reason to question the veracity of Speaker Abeywardena’s account of his meeting with the then Indian High Commissioner, in the Speaker’s parliamentary office. But what is amusing is the use of this single data point of a meeting between the High Commissioner and the Speaker – to draw a line of conclusion in two directions: (1) a causal line going backward to suggest that the entire Aragalaya phenomenon was potentially orchestrated by India and America; and (2) a consequential line going forward to the election of the NPP government with the assertion that the new government came into office after displacing Gotabaya Rajapaksa to serve Sri Lanka’s two masters – India and the US. The people of Sri Lanka are reduced to doormats in this political theatre and their votes were political counterfeits to elect a government of fake Marxists. Even Trump would be impressed by this creativity.

As amusements go, this genre of political punditry is fully supplemented by the NPP’s current critics and quondam comrades from the bookish left (as Philip Gunawardena used to scoff). They take NPP to task for any and all of its actions and non-actions – from its apparent ambivalence towards Israel to its alleged foot dragging on the Prevention of Terrorism Act, not to mention its similarly alleged kneeling before the IMF.

The criticisms themselves are not inaccurate, but their tone and timing do not appear to be intended for any positive outcome. They are also esoteric and out of place in a situation when the country has been ravaged by a torrential cyclone. I will conclude by paraphrasing a witty response to a recent online critique of the NPP on the PTA matter: in blaming the NPP government for not repealing all the bad laws enacted by every previous government, are we not forgetting that the NPP is the only government that is – not only against making use of bad laws enacted by others, but also against enacting any new bad law of its own.

by Rajan Philips ✍️

Features

2025: The Year We Let It Happen

“I was saved by God to make America great again,” Donald Trump said, a line that circulated widely during his political comeback rallies. “The golden age of America begins right now,” Trump declared as he was inaugurated for a second term on 20 January 2025, marking a major shift in US politics with consequences likely to extend across generations. Trump’s appeal lay not in moderation but in confrontation, rooted in the assertion that democracy works best when it produces winners unencumbered by restraint. He rewarded many who delivered him power, while leaders in other democracies often spent their mandates managing survival and retreating from pledges once deemed non-negotiable. The old Marxian line about history repeating itself as tragedy and farce felt newly apt as elections continued to produce both at once.

While deteriorating democratic systems grappled with their contradictions, quasi-democratic and openly authoritarian administrations pursued power with less ceremony. Beijing tightened its hold over Taiwan, Tibet, and Hong Kong while projecting its global power with mixed success, and Moscow prosecuted its war in Ukraine with brutal persistence, accepting sanctions and isolation as the cost of imperial memory. The EU’s plan to use frozen Russian funds for Kyiv stalled and was replaced by a €90 billion loan package, which will cost taxpayers around €3 billion annually in interest. Pyongyang continued its missile testing, while its state-linked hackers reportedly stole an estimated $2.02 billion in cryptocurrency in 2025 alone. Tehran, for its part, passed another turbulent year, marked by a 12-day military confrontation with Israel in June 2025 that inflicted significant damage on both countries. Power in these systems remained centralized and unapologetic, justified by security and sustained by fear.

Across the globe, 2025 witnessed a wave of Gen Z-led protests that challenged authority and disrupted the social order in ways reminiscent of the Arab Spring, yet carried their own perils. From climate strikes in London and Berlin to anti-corruption demonstrations in São Paulo, Mexico City, Dhaka, and Kathmandu, young activists confronted entrenched elites with unprecedented energy and digital coordination. In Morocco, Madagascar, Tunisia, Indonesia, and the Philippines, student-led and youth-driven uprisings rattled governments, while in the United States, marches over climate action and student debt repeatedly clashed with authorities.

Even in authoritarian countries such as Iran, Vietnam, and, to some extent, Thailand, clandestine movements mobilized online and in the streets, forcing concessions while provoking brutal crackdowns. Yet these eruptions of youthful revolt, as electrifying as they were, revealed a dangerous pattern: like the Arab Spring, the protests often destabilized societies without delivering durable reform, leaving governments weakened, institutions strained, and political vacuums that could be exploited by opportunistic elites. The Gen Z moment in 2025 was a showcase of idealism and impatience, but also a warning that the seductive energy of revolt can become the architect of new disorder and unfulfilled promise. The question remains: who will have the last laugh?

The dissonance between public display and private conclave became starkly visible in Beijing in September 2025 during the 80th-anniversary commemorations of the end of the Second World War. State television followed Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin as they approached the parade ground, and microphones accidentally left live picked up a fragment of conversation that ricocheted around the world. According to reports, Putin’s interpreter was heard saying, “Human organs can be continuously transplanted. The longer you live, the younger you become,” to which Xi replied, “Some predict that in this century humans may live to 150 years old.”

The Kremlin later confirmed the exchange, insisting it was a casual discussion about medical advances, not a policy statement. Yet the symbolism was hard to miss: two leaders whose authority rests on longevity speculating, however lightly, about defeating mortality itself. In a century marked by demographic decline in both Russia and China, the fantasy of extended life carried political weight.

That moment intersected with a broader obsession that cut across systems: the promise and threat of artificial intelligence. Governments unable to agree on climate targets found common urgency in machine learning, particularly its military and medical applications. The United States National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence warned in 2021 that AI would “accelerate the speed of warfare beyond human comprehension”. By 2025, the Pentagon had embedded AI across military operations, deploying commercial models and prioritizing generative tools to maintain America’s technological edge.

Project Stargate, a high-profile initiative with commitments from OpenAI, Microsoft, Nvidia, Oracle, and SoftBank, was said to involve hundreds of billions of dollars in public-private investment to expand AI infrastructure and research across sectors. In parallel, China’s state and corporate ecosystems together channeled tens of billions into AI development, sustaining the world’s second-largest cluster of AI firms and an expanding suite of generative tools. Critical minerals remained a strategic fulcrum, with China controlling more than 90 per cent of global rare-earth processing capacity and wielding that dominance as leverage over technology and defence supply chains.

Space in 2025 saw competition in orbit intensify rather than abate. The number of active satellites in low Earth orbit surpassed 9,350, led by SpaceX’s Starlink constellation, which accounts for the largest share of operational spacecraft. The Space Development Agency awarded US$3.5 billion in contracts for 72 new infrared tracking satellites to strengthen missile-warning and defence architecture. China’s on-orbit presence also expanded markedly in 2025, with Beijing conducting a record number of launches and placing hundreds of satellites into space to advance communications and surveillance networks, including early deployments for its ambitious Guowang low Earth orbit mega constellation. Close encounters between Chinese, Russian, and Western satellites exposed weak space-traffic coordination, with orbit increasingly framed in martial rather than peaceful terms.

On the ground, the uglier side of power refused to remain hidden. In the United States, the Epstein Files Transparency Act compelled the Department of Justice to disclose federal records by mid-December, but heavy redactions and omissions drew bipartisan criticism from lawmakers who argued the release undermined the law’s intent and shielded powerful individuals. Thousands of pages referenced disturbing allegations and reinforced a widely held sense that wealth and influence can insulate the well-connected from scrutiny or accountability. Elsewhere, established democracies continued to confront systemic failures: France grappled with unresolved clerical abuse scandals; Britain faced renewed criticism over policing gaps in handling grooming gangs; and India’s chronic under-reporting of sexual violence remained a persistent human rights concern.

Meanwhile, the language of peace was deployed with similar cynicism. Trump repeatedly suggested he deserved the Nobel Peace Prize, citing what he described as a series of peace initiatives in which he claimed to have played a decisive role. These included the Abraham Accords of 2020, which normalized relations between Israel and several Arab states, and the 2025 United States-brokered ceasefire in Gaza, under which all remaining living Israeli hostages held by Hamas were released and hostilities were paused through a phased arrangement.

Trump further asserted that his administration had “settled” or eased a widening range of conflicts, pointing to diplomatic efforts aimed at initiating talks towards a negotiated end to the Russia–Ukraine war, although substantive peace terms remain elusive and negotiations continue amid resistance from Kyiv, Moscow, and key European Union states. He also publicly referenced conflicts or diplomatic tracks involving India and Pakistan; Thailand and Cambodia; Kosovo and Serbia; the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Rwanda; Israel and Iran; Egypt and Ethiopia; and Armenia and Azerbaijan as evidence of his claimed peacemaking credentials, despite the absence of durable or comprehensive peace settlements in any of these cases.

Trump did not receive the Nobel Prize, whose awards have often favoured aspiration over results. Instead, it went to María Corina Machado, a Venezuelan opposition leader who told me in 2020 that “a mafia group has destroyed my beloved nation, Venezuela”, and whom Washington now treats as a key ally. Meanwhile, the United States has reportedly sought to seize another oil tanker linked to Caracas while pursuing an alleged drug cartel, amid claims that the Secretary of War ordered forces to “kill them all”. At the same time, Latin America has seen a significant rise in right-wing politics, with Argentina’s Javier Milei consolidating power, Chile electing far-right leader José Antonio Kast, and conservative presidents such as Daniel Noboa in Ecuador and Nayib Bukele in El Salvador gaining influence amid broader regional shifts to the right.

Africa was not immune to global disorder. In Sudan, a brutal civil war between the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and rival factions continued throughout 2025, marked by repeated mass atrocities, including ongoing killings around El Fasher in North Darfur that left tens of thousands dead and displaced millions, making it one of the world’s most devastating humanitarian crises. The United Nations and humanitarian agencies reported widespread executions, sexual violence, and attacks on civilians and health facilities. Meanwhile, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, fighting between the Congolese army and the Rwanda-linked M23 rebel group forced thousands to flee, with more than 84,000 refugees crossing into neighbouring Burundi in 2025.

Nigeria’s security situation also deteriorated, with jihadist factions, including Boko Haram and Islamic State West Africa Province, expanding operations and causing civilian casualties and displacement. Across West Africa, political realignment followed coups in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, which jointly withdrew from ECOWAS and formed the Alliance of Sahel States, commonly dubbed the “African NATO”. The bloc has announced plans to establish a shared central bank and investment fund aimed at economic autonomy and reducing reliance on traditional financial systems, but it remains too early to assess its capacity to curb the continent’s growing Islamic extremism and militant gangs.

Through all this, inequality hardened. The latest World Inequality Report 2026 showed that the richest 0.001 per cent of adults — fewer than 60,000 individuals — now control three times more wealth than the poorest half of the global population combined, while the richest 10 per cent own around three-quarters of global wealth. While leaders speculated about extended lifespans and investors poured money into longevity start-ups, life expectancy stagnated or fell in several countries: in the United States it remained lower than a decade earlier, and in parts of sub-Saharan Africa gains were erased by conflict and weak health systems.

Orwell’s line continues to resonate, even at the risk of banality: “All animals are equal, but some are more equal than others.” The events of this year have not disproved it; they have updated it with satellites, algorithms, and offshore accounts. Power now moves faster and hides better, but it still feeds on the same asymmetries. As another year closes, the temptation is to wish for renewal without reckoning. That wish has become a luxury. The facts are stubborn: inequality widens, wars persist, technology accelerates without consensus, and leaders speak of salvation while tolerating cruelty. New Year greetings sound hollow against that record, but perhaps honesty is a start. The age we are entering will not be golden by proclamation; it will be judged, as ever, by who is allowed to live with dignity — and who is told, politely or otherwise, to wait. To the New Year — hopefully wiser.

by Nilantha Ilangamuwa ✍️

Features

After Christmas Day

We are in this period – the days immediately following Christmas – December 25. The intense religious and festive two days are over, but just as the festive season precedes Christmas Day, it follows it too, notwithstanding the day that marks the beginning of the new year.

Christmas is significant, I need not even mention, as the celebration of Jesus Christ’s birth in Bethlehem in a manger as there was no room at the inn. It however symbolizes God‘s love and salvation for his ‘children’. People make merry with traditional gift giving (custom from the three kings), carols, bright lights concentrated in indoor fir trees and general goodwill epitomized by jolly old Santa. It is also a time of spiritual reflection on God’s love of people by his giving his son to their will.

The day after Christmas – 26 December – is also a day marked in the calendar of the festive season. Named Boxing Day, it too is a holiday of fun. Originally a day of generosity and giving gifts to those in need, it has evolved to become a part of Christmas festivities. It originated in the UK and is observed by several Commonwealth countries, including Ceylon.

It is concurrent with the Christian festival of Saint Stephen’s Day, which in many European countries is considered the second day of Christmas. It honours St. Stephen who was the first Christian martyr who was stoned to death for his faith. More commonly, it is called Boxing Day, also known as Offering Day, for giving servants and the needy gifts and financial help. The term boxing comes from the noun boxes, because alms were collected in boxes placed in Churches and opened for distribution on the day after Christmas. This day is first mentioned in the Oxford English Dictionary on 1743.

The Twelve Days of Christmas follow the 25th and make up the Christmas Season. It marks the days the kings of Orienta –Magi – took to visit the infant Jesus with gifts of gold, myrrh and frankincense, symbolizing Christ’s royalty, future suffering and divinity/ priesthood respectively.

The “Twelve days of Christmas” we know as a Christmas carol or children’s nursery rhyme which is cumulative with each verse built on the previous verse. Content of the verses is what the lover gives his /her true love on each of twelve days beginning with Christmas day, so it ends on January 6, which marks the end of the Xmas season. The carol was first published in England in the late 18th century. The best known version is that of Frederic Austen who wrote his rhymes in 1909.

“On the first day of Christmas my true love sent to me

A partridge in a pear tree.

On the second day of Christmas my true love sent to me

Two turtle doves

And a partridge in a pear tree.”

And so on with three hens, four calling birds; five gold rings, six geese a-laying, seven swans a-swimming, eight maids a-milking, nine ladies dancing, ten lords a-leaping, eleven pipers piping, twelve drummers drumming. But the most important fact is that each animal or human represents a Christian object or key tenet of the faith, serving as a religious tool where each gift depicts a religious concept.

For instance, it is believed the partridge symbolizes Jesus and two turtle doves represent the Old and New Testaments. Doves are symbols of truth and peace, once again reinforcing the tie to Christ and Christmas. Reference is also made to the Ten Commandments, the 12 Apostles and the Creed. However, this is a popular theory and not a historic fact with some believing it is a love song pure and simple.

And so 2025 draws to an end. One cannot but throw one’s thoughts back to when one was an eager beaver child. Buddhist though I was, I attended a Christian school from Baby Class and was very influenced by the Christian faith. In fact, an older sister was so indoctrinated she wanted to convert to Christianity. Our Methodist missionary school did not encourage conversions.

Mother was unaware of this great attraction; her emphasis was on an English education for her children,. But being so drawn to the Christian religion with all its celebration and merriment was no surprise, added to the fact that Vesak was such a solemn occasion with sil redi restraint and the death of the Buddha too commemorated.

It is a very heartening fact that in this country Buddhists too join in the pleasures of Christmas. Many go for Midnight Mass on 24th because of religiously mixed marriages or merely to enjoy that experience too. Our family, when the children were young, invariably celebrated with the traditional XMas tree in the house with my husband taking great pleasure in buying a branch of a cypress tree sold in Colombo, and decorating it. We often spent the holiday in Bandarawela and so Christmas became extra special with the strong smell of the tree branch bought indoors. Santa visited my young one for long years; he being a strong believer in the delightful myth.

Delightful memories are made of these…

I wish everyone a wonderful Christmas. Let’s substitute the sorrows and despair of the aftermath of the cyclone and give ourselves, all Sri Lankans, a break and renew our togetherness and one-ness as a nation of decent people..

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoMembers of Lankan Community in Washington D.C. donates to ‘Rebuilding Sri Lanka’ Flood Relief Fund

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoBritish MP calls on Foreign Secretary to expand sanction package against ‘Sri Lankan war criminals’

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoAir quality deteriorating in Sri Lanka

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoCardinal urges govt. not to weaken key socio-cultural institutions

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoGeneral education reforms: What about language and ethnicity?

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days agoRanwala crash: Govt. lays bare its true face

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoSuspension of Indian drug part of cover-up by NMRA: Academy of Health Professionals

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoCID probes unauthorised access to PNB’s vessel monitoring system