Features

JVP and the Cost of Lost Revolution

By Indrawansa de Silva, Ph.D.

Professor Emeritus, USA

Fifty years ago, thousands of us took to arms in what we thought was the Marxist-Leninist revolution to capture power of the state overnight. That’s what our Dear Leader promised. We were made to believe that it was a well-thought out plan of action guided by field-tested Marxist theory. We had no doubt, especially in the early days, that our leader, Comrade Rohana Wijeweera, with his commanding knowledge of Marxist-Leninist Maoist ideology and an intimate knowledge of guerilla warfare fine-tuned by none other than Che Guevara, knew what he was talking about.

The fifth of the now legendary five “Classes” was fully devoted to the game plan of Lankan revolution. That Class was aptly titled “The path Lankan revolution should take.” It summed up all the Marxist revolutions that had taken place since the Bolsheviks toppled the Czar in 1917 and quite convincingly argued to slack-jawed audiences why none of the past revolutions could be a template to the “unique conditions” of the motherland. How original, we thought. So, it was our Dear Leader who dreamed up what the Lankan revolution would be: a simultaneous attack on the police stations and strategically selected Army camps. The entire attack would take a single night.

We know how that fateful night ended fifty years ago. All told, about five thousand youth died in their prime and more than twenty thousand of us were rounded up and corralled to overflowing prisons, subjected to every torture technique in the book plus new ones. We all remember the horrifying incident of the 20-year old beauty queen of Kataragama, Prema Manamperi, who was tortured overnight and paraded nude in broad daylight and summarily executed in full view of the public on April 17, 1971. That sadistic brutality was just the tip of the iceberg of torture that took place behind the closed doors. The very universities many of us attended were converted into makeshift prisons. Tens of thousands of families were destroyed, their homes torched and the impact of that naïve adventure is still raw. For those of us who took part in that uprising and for the country that was so scarred, an important question still remains: What, as a nation, have we learned?

Like many of my fellow comrades I was barely 17 years old when I was “hooked” – JVP terminology – to JVP. Everything I knew about Marxism, Leninism, Stalinism, Maoism and the glorious Cuban Revolution, I learned in my late teens from the clandestine classes and political camps as well as from the propaganda material quite generously handed out to us by the Soviet, Chinese and North Korean embassies. I was well schooled in revolutionary ideology. And the secrecy of every aspect of our revolution kept my adrenaline running high at all times. I was busy. Enlarging the maps of Colombo district, marking bridges to be blown up so we could immobilize the army, pinpointing where the counter revolutionaries, reactionaries and traitors reside so we could “take care” of them when we gained power. I even had my blue uniform made and waited for my tetanus shot. Ready to revolt. It was my drug of choice. We were different from the lumpen proletariat surrounding us. I, like all of us, did not smoke or drank. No relationships. Even personal hygiene such as bathing regularly, was looked down as petit bourgeois and unkempt hair was part of the trademark. (Only later did we come to know that most of these cultist taboos did not apply to our leaders.) Our devotion to the cause and the proletariat class made us feel unique and special. I “knew” I was right and anyone who questioned what we were espousing or even dared to suggest that we could be wrong was either a reactionary, a traitor or class-enemy. Branding the enemy came quite easily. Their number would be up very soon.

Like many of my fellow comrades I was barely 17 years old when I was “hooked” – JVP terminology – to JVP. Everything I knew about Marxism, Leninism, Stalinism, Maoism and the glorious Cuban Revolution, I learned in my late teens from the clandestine classes and political camps as well as from the propaganda material quite generously handed out to us by the Soviet, Chinese and North Korean embassies. I was well schooled in revolutionary ideology. And the secrecy of every aspect of our revolution kept my adrenaline running high at all times. I was busy. Enlarging the maps of Colombo district, marking bridges to be blown up so we could immobilize the army, pinpointing where the counter revolutionaries, reactionaries and traitors reside so we could “take care” of them when we gained power. I even had my blue uniform made and waited for my tetanus shot. Ready to revolt. It was my drug of choice. We were different from the lumpen proletariat surrounding us. I, like all of us, did not smoke or drank. No relationships. Even personal hygiene such as bathing regularly, was looked down as petit bourgeois and unkempt hair was part of the trademark. (Only later did we come to know that most of these cultist taboos did not apply to our leaders.) Our devotion to the cause and the proletariat class made us feel unique and special. I “knew” I was right and anyone who questioned what we were espousing or even dared to suggest that we could be wrong was either a reactionary, a traitor or class-enemy. Branding the enemy came quite easily. Their number would be up very soon.

It is quite clear that we believed in violence from the outset. It was in our party’s DNA. We openly promoted the Marxist-Leninist-Maoist violent revolution in anticipation of proletariat dictatorship. We were in agreement with Mao when he said that political power grows out of the barrel of a gun. A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another. Our writings, classes, publications, posters and public speeches were very open about our belief in violence. Destruction must precede construction, whether it is imperialism, capitalism, feudalism or the State machinery. And if we were to kill en masse to reach our goal so be it. We didn’t shy away from saying how brutal we could be. One of our posters read: The liberation of the masses won’t come until the last capitalist is hanged from the last imperialist’s bowels! – JVP.

Incidentally, this was the time Mao’s Cultural Revolution was taking place in full throttle and I remember how approvingly we talked about that mass murder campaign. According to Mao successful revolution wouldn’t guarantee socialism and occasional cleansing of the party and the society from the reactionary and petit bourgeois mindset is a must. We were in total agreement with Mao on that. Absent cultural revolution a nation would end like Khrushchev’s Russia, revisionist! We celebrated Chairman Mao’s improvements to “scientific” Marxist-Leninist theory. It would take another decade for me to truly understand what a murderous enterprise Mao had launched as a cultural revolution. By then Communist China was in top gear towards capitalism and Deng Xiaoping was telling people that to get rich was glorious. A bit too late, Comrade Deng.

What would Sri Lanka have been if the JVP had captured power in 1971? I am not sure about the JVP establishing a proletariat dictatorship, but I am quite sure about Wijeweera establishing a dictatorship. And because of that, like many of my fellow revolutionaries, I am glad that we did not succeed in 1971. I say this with a very heavy heart as thousands of courageous, caring and very patriotic youth died for this misguided “revolution.” Had we succeeded it is more than likely that Sri Lanka would have ended up worse than Cambodia under Pol Pot. I am not being just speculative here. The JVP has shown time after time its violent and authoritarian tendencies whenever and wherever it got even a small taste of power. Just take some early signs. If someone with an opposing view tried to sell a newspaper or distribute a pamphlet at our rallies they were promptly beaten up and kicked out. We did not hesitate to use power of the fist when met with opposition even within the organisation. Honest and sincere questioning of ideas and theories we espoused in our classes and camps was seen as a threat to the movement and branded as reactionary, counter-revolutionary, or petit bourgeois tendencies.

The JVP is intolerant of challenge. I left the JVP in 1971 on principle, like many others, but we were always under its radar. In 1977, I was the President of the Students’ Council of Vidyodaya Campus and of the Inter-University Students’ Federation when Wijeweera was released from prison and held his first rally at the Hyde Park. He openly threatened me as we were a major challenge to the JVP on university campuses. The winds of terror were such that I left the country in the mid-1980s. There is not an iota of doubt in my mind that I would have been killed by the JVP, had I stayed. Looking back, the JVP’s talk about “centralised democracy” in theory is the biggest running joke. The JVP has proven that it doesn’t have a single democratic bone in its body.

The best example of how JVP would have governed comes from Hammenheil Prison in Jaffna, where hundreds of JVP cadres were held right after the uprising. In his excellent memoir, Tears of April (Bak Maha Kandulu), Ranjith Henayake Arachchi (Bertie) describes leading the attack on the Jaffna prison in an attempt to get Wijeweera rescued and its tragic consequences. He recounts how, in a remarkable show of courage and determination, the political prisoners in Hammenheil ended up winning some fundamental rights to take care of themselves inside the walls of the prison. In no time, Ranjith continues, the JVP equated that mutiny to a socialist revolution and claimed ownership of it. A “revolutionary army” was established to safeguard the “proletariat dictatorship” in Hammenheil that promptly took care of the “class-enemies” and “traitors” in the only way known to JVP––physical force. Anyone who questioned anything the JVP was up to was branded as the class enemy. According to Ranjith, those who cried for help when brutally beaten in broad daylight by the “revolutionary army” had only “shown their true colours as class-enemies.” Kangaroo courts (aka Peoples’ Court) were held in Hammenheil to try “reactionaries” and “counter-revolutionaries” whom the JVP always found guilty as charged with deadly consequences. Everything that took place in Hammenheil had the blessings of Wijeweera himself as there was an effective line of communication between Hammenheil and Jaffna prison where he was held. ‘The Socialist Republic of Hammenheil’ was a microcosm of what the country would have become had the JVP ever grabbed power.

Looking back, it appears that Sri Lanka has instinctively realised what JVP is: a brutal political entity. A wolf in sheep’s clothing. Underneath its flowery rhetoric of democracy, liberty, secularism and freedom of the press and speech, the JVP remains true to its origins fifty plus years ago. Its insatiable appetite for violence as a means to achieve power was vividly shown in the late 1980s. This may be the reason that JVP was never able to break the four-percent barrier – the percentage of votes it has consistently received since it entered parliamentary politics.

The JVP seems immune to the humiliating rejections from the North and the East at every election it contested in those districts. Minorities in the North and the East appear to recognise the racism running in JVP’s veins since it tried to sugarcoat its racist views from the outset under the guise of so-called Indian expansion.

Over the past fifty years, the JVP had many opportunities to come clean of its sins but it hasn’t even tried to pretend it will do so. The JVP has done nothing wrong, the argument goes. All the carnage it created was the results of “reactionaries” “traitors” and the “class-enemies” who infiltrated the party to destroy it. At a forum in Europe, when faced with the question of atrocities committed during the so-called second uprising in the late 1980s, the current leader of JVP sought the cover of Mao’s rhetoric again: revolution is not a dinner party, he answered.

It is high time the JVP got its head out of the sand and face the jury of history. It owes that much to the thousands of youth still seeking its refuge for a political future.

Features

An innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

After nearly two decades of on-and-off negotiations that began in 2007, India and the European Union formally finally concluded a comprehensive free trade agreement on 27 January 2026. This agreement, the India–European Union Free Trade Agreement (IEUFTA), was hailed by political leaders from both sides as the “mother of all deals,” because it would create a massive economic partnership and greatly increase the current bilateral trade, which was over US$ 136 billion in 2024. The agreement still requires ratification by the European Parliament, approval by EU member states, and completion of domestic approval processes in India. Therefore, it is only likely to come into force by early 2027.

An Innocent Bystander

When negotiations for a Free Trade Agreement between India and the European Union were formally launched in June 2007, anticipating far-reaching consequences of such an agreement on other developing countries, the Commonwealth Secretariat, in London, requested the Centre for Analysis of Regional Integration at the University of Sussex to undertake a study on a possible implication of such an agreement on other low-income developing countries. Thus, a group of academics, led by Professor Alan Winters, undertook a study, and it was published by the Commonwealth Secretariat in 2009 (“Innocent Bystanders—Implications of the EU-India Free Trade Agreement for Excluded Countries”). The authors of the study had considered the impact of an EU–India Free Trade Agreement for the trade of excluded countries and had underlined, “The SAARC countries are, by a long way, the most vulnerable to negative impacts from the FTA. Their exports are more similar to India’s…. Bangladesh is most exposed in the EU market, followed by Pakistan and Sri Lanka.”

Trade Preferences and Export Growth

Normally, reduction of price through preferential market access leads to export growth and trade diversification. During the last 19-year period (2015–2024), SAARC countries enjoyed varying degrees of preferences, under the EU’s Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP). But, the level of preferential access extended to India, through the GSP (general) arrangement, only provided a limited amount of duty reduction as against other SAARC countries, which were eligible for duty-free access into the EU market for most of their exports, via their LDC status or GSP+ route.

However, having preferential market access to the EU is worthless if those preferences cannot be utilised. Sri Lanka’s preference utilisation rate, which specifies the ratio of eligible to preferential imports, is significantly below the average for the EU GSP receiving countries. It was only 59% in 2023 and 69% in 2024. Comparative percentages in 2024 were, for Bangladesh, 96%; Pakistan, 95%; and India, 88%.

As illustrated in the table above, between 2015 and 2024, the EU’s imports from SAARC countries had increased twofold, from US$ 63 billion in 2015 to US$ 129 billion by 2024. Most of this growth had come from India. The imports from Pakistan and Bangladesh also increased significantly. The increase of imports from Sri Lanka, when compared to other South Asian countries, was limited. Exports from other SAARC countries—Afghanistan, Bhutan, Nepal, and the Maldives—are very small and, therefore, not included in this analysis.

Why the EU – India FTA?

With the best export performance in the region, why does India need an FTA with the EU?

Because even with very impressive overall export growth, in certain areas, India has performed very poorly in the EU market due to tariff disadvantages. In addition to that, from January 2026, the EU has withdrawn GSP benefits from most of India’s industrial exports. The FTA clearly addresses these challenges, and India will improve her competitiveness significantly once the FTA becomes operational.

Then the question is, what will be its impact on those “innocent bystanders” in South Asia and, more particularly, on Sri Lanka?

To provide a reasonable answer to this question, one has to undertake an in-depth product-by-product analysis of all major exports. Due to time and resource constraints, for the purpose of this article, I took a brief look at Sri Lanka’s two largest exports to the EU, viz., the apparels and rubber-based products.

Fortunately, Sri Lanka’s exports of rubber products will be only nominally impacted by the FTA due to the low MFN duty rate. For example, solid tyres and rubber gloves are charged very low (around 3%) MFN duty and the exports of these products from Sri Lanka and India are eligible for 0% GSP duty at present. With an equal market access, Sri Lanka has done much better than India in the EU market. Sri Lanka is the largest exporter of solid tyres to the EU and during 2024 our exports were valued at US$180 million.

On the other hand, Tariffs MFN tariffs on Apparel at 12% are relatively high and play a big role in apparel sourcing. Even a small difference in landed cost can shift entire sourcing to another supplier country. Indian apparel exports to the EU faced relatively high duties (8.5% – 12%), while competitors, such as Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, are eligible for preferential access. In addition to that, Bangladesh enjoys highly favourable Rules of Origin in the EU market. The impact of these different trade rules, on the EU’s imports, is clearly visible in the trade data.

During the last 10 years (2015-2024), the EU’s apparel imports from Bangladesh nearly doubled, from US$15.1 billion, in 2015, to US$29.1 billion by 2024, and apparel imports from Pakistan more than doubled, from US$2.3 billion to US$5.5 billion. However, apparel imports from Sri Lanka increased only from US$1.3 billion in 2015 to US$2.2 billion by 2024. The impressive export growth from Pakistan and Bangladesh is mostly related to GSP preferences, while the lackluster growth of Sri Lankan exports was largely due to low preference utilisation. Nearly half of Sri Lanka’s apparel exports faced a 12% tariff due to strict Rules of Origin requirements to qualify for GSP.

During the same period, the EU’s apparel imports from India only showed very modest growth, from US$ 5.3 billion, in 2015, to US$ 6.3 billion in 2024. The main reason for this was the very significant tariff disadvantage India faced in the EU market. However, once the FTA eliminates this gap, apparel imports from India are expected to grow rapidly.

According to available information, Indian industry bodies expect US$ 5-7 billion growth of textiles and apparel exports during the first three years of the FTA. This will create a significant trade diversion, resulting in a decline in exports from China and other countries that do not enjoy preferential market access. As almost half of Sri Lanka’s apparel exports are not eligible for GSP, the impact on our exports will also be fierce. Even in the areas where Sri Lanka receives preferential duty-free access, the arrival of another large player will change the market dynamics greatly.

A Passive Onlooker?

Since the commencement of the negotiations on the EU–India FTA, Bangladesh and Pakistan have significantly enhanced the level of market access through proactive diplomatic interventions. As a result, they have substantially increased competitiveness and the market share within the EU. This would help them to minimize the adverse implications of the India–EU FTA on their exports. Sri Lanka’s exports to the EU market have not performed that well. The challenges in that market will intensify after 2027.

As we can clearly anticipate a significant adverse impact from the EU-India FTA, we should start to engage immediately with the European Commission on these issues without being passive onlookers. For example, the impact of the EU-India FTA should have been a main agenda item in the recently concluded joint commission meeting between the European Commission and Sri Lanka in Colombo.

Need of the Hour – Proactive Commercial Diplomacy

In the area of international trade, it is a time of turbulence. After the US Supreme Court judgement on President Trump’s “reciprocal tariffs,” the only prediction we can make about the market in the United States market is its continued unpredictability. India concluded an FTA with the UK last May and now the EU-India FTA. These are Sri Lanka’s largest markets. Now to navigate through these volatile, complex, and rapidly changing markets, we need to move away from reactive crisis management mode to anticipatory action. Hence, proactive commercial diplomacy is the need of the hour.

(The writer can be reached at senadhiragomi@gmail.com)

By Gomi Senadhira

Features

Educational reforms: A perspective

Dr. B.J.C. Perera (Dr. BJCP) in his article ‘The Education cross roads: Liberating Sri Lankan classroom and moving ahead’ asks the critical question that should be the bedrock of any attempt at education reform – ‘Do we truly and clearly understand how a human being learns? (The Island, 16.02.2026)

Dr. BJCP describes the foundation of a cognitive architecture taking place with over a million neural connections occurring in a second. This in fact is the result of language learning and not the process. How do we ‘actually’ learn and communicate with one another? Is a question that was originally asked by Galileo Galilei (1564 -1642) to which scientists have still not found a definitive answer. Naom Chomsky (1928-) one of the foremost intellectuals of our time, known as the father of modern linguistics; when once asked in an interview, if there was any ‘burning question’ in his life that he would have liked to find an answer for; commented that this was one of the questions to which he would have liked to find the answer. Apart from knowing that this communication takes place through language, little else is known about the subject. In this process of learning we learn in our mother tongue and it is estimated that almost 80% of our learning is completed by the time we are 5 years old. It is critical to grasp that this is the actual process of learning and not ‘knowledge’ which tends to get confused as ‘learning’. i.e. what have you learnt?

The term mother tongue is used here as many of us later on in life do learn other languages. However, there is a fundamental difference between these languages and one’s mother tongue; in that one learns the mother tongue- and how that happens is the ‘burning question’ as opposed to a second language which is taught. The fact that the mother tongue is also formally taught later on, does not distract from this thesis.

Almost all of us take the learning of a mother tongue for granted, as much as one would take standing and walking for granted. However, learning the mother tongue is a much more complex process. Every infant learns to stand and walk the same way, but every infant depending on where they are born (and brought up) will learn a different mother tongue. The words that are learnt are concepts that would be influenced by the prevalent culture, religion, beliefs, etc. in that environment of the child. Take for example the term father. In our culture (Sinhala/Buddhist) the father is an entity that belongs to himself as well as to us -the rest of the family. We refer to him as ape thaththa. In the English speaking (Judaeo-Christian) culture he is ‘my father’. ‘Our father’ is a very different concept. ‘Our father who art in heaven….

All over the world education is done in one’s mother tongue. The only exception to this, as far as I know, are the countries that have been colonised by the British. There is a vast amount of research that re-validates education /learning in the mother tongue. And more to the point, when it comes to the comparability of learning in one’s own mother tongue as opposed to learning in English, English fails miserably.

Education /learning is best done in one’s mother tongue.

This is a fact. not an opinion. Elegantly stated in the words of Prof. Tove Skutnabb-Kangas-“Mother tongue medium education is controversial, but ‘only’ politically. Research evidence about it is not controversial.”

The tragedy is that we are discussing this fundamental principle that is taken for granted in the rest of the world. It would not be not even considered worthy of a school debate in any other country. The irony of course is, that it is being done in English!

At school we learnt all of our subjects in Sinhala (or Tamil) right up to University entrance. Across the three streams of Maths, Bio and Commerce, be it applied or pure mathematics, physics, chemistry, zoology, botany economics, business, etc. Everything from the simplest to the most complicated concept was learnt in our mother tongue. An uninterrupted process of learning that started from infancy.

All of this changed at university. We had to learn something new that had a greater depth and width than anything we had encountered before in a language -except for a very select minority – we were not at all familiar with. There were students in my university intake that had put aside reading and writing, not even spoken English outside a classroom context. This I have been reliably informed is the prevalent situation in most of the SAARC countries.

The SAARC nations that comprise eight countries (Sri Lanka, Maldives, India, Pakistan Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Bhutan) have 21% of the world population confined to just 3% of the earth’s land mass making it probably one of the most densely populated areas in the world. One would assume that this degree of ‘clinical density’ would lead to a plethora of research publications. However, the reality is that for 25 years from 1996 to 2021 the contribution by the SAARC nations to peer reviewed research in the field of Orthopaedics and Sports medicine- my profession – was only 1.45%! Regardless of each country having different mother tongues and vastly differing socio-economic structures, the common denominator to all these countries is that medical education in each country is done in a foreign language (English).

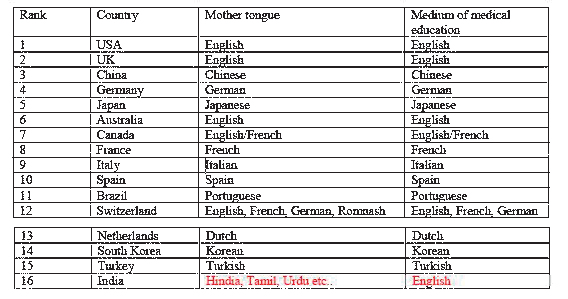

The impact of not learning in one’s mother tongue can be illustrated at a global level. This can be easily seen when observing the research output of different countries. For example, if one looks at orthopaedics and sports medicine (once again my given profession for simplicity); Table 1. shows the cumulative research that has been published in peer review journals. Despite now having the highest population in the world, India comes in at number 16! It has been outranked by countries that have a population less than one of their states. Pundits might argue giving various reasons for this phenomenon. But the inconvertible fact remains that all other countries, other than India, learn medicine in their mother tongue.

(See Table 1) Mother tongue, medium of education in country rank order according to the volume of publications of orthopaedics and sports medicine in peer reviewed journals 1996 to 2024. Source: Scimago SCImago journal (https://www.scimagojr.com/) has collated peer review journal publications of the world. The publications are categorized into 27 categories. According to the available data from 1996 to 2024, China is ranked the second across all categories with India at the 6th position. China is first in chemical engineering, chemistry, computer science, decision sciences, energy, engineering, environmental science, material sciences, mathematics, physics and astronomy. There is no subject category that India is the first in the world. China ranks higher than India in all categories except dentistry.

The reason for this difference is obvious when one looks at how learning is done in China and India.

The Chinese learn in their mother tongue. From primary to undergraduate and postgraduate levels, it is all done in Chinese. Therefore, they have an enormous capacity to understand their subject matter just not itself, but also as to how it relates to all other subjects/ themes that surround it. It is a continuous process of learning that evolves from infancy onwards, that seamlessly passes through, primary, secondary, undergraduate and post graduate education, research, innovation, application etc. Their social language is their official language. The language they use at home is the language they use at their workplaces, clubs, research facilities and so on.

In India higher education/learning is done in a foreign language. Each state of India has its own mother tongue. Be it Hindi, Tamil, Urdu, Telagu, etc. Infancy, childhood and school education to varying degrees is carried out in each state according to their mother tongue. Then, when it comes to university education and especially the ‘science subjects’ it takes place in a foreign tongue- (English). English remains only as their ‘research’ language. All other social interactions are done in their mother tongue.

India and China have been used as examples to illustrate the point between learning in the mother tongue and a foreign tongue, as they are in population terms comparable countries. The unpalatable truth is that – though individuals might have a different grasp of English- as countries, the ability of SAARC countries to learn and understand a subject in a foreign language is inferior to the rest of the world that is learning the same subject in its mother tongue. Imagine the disadvantage we face at a global level, when our entire learning process across almost all disciplines has been in a foreign tongue with comparison to the rest of the world that has learnt all these disciplines in their mother tongue. And one by-product of this is the subsequent research, innovation that flows from this learning will also be inferior to the rest of the world.

All this only confirms what we already know. Learning is best done in one’s mother tongue! .

What needs to be realised is that there is a critical difference between ‘learning English’ and ‘learning in English’. The primary-or some may argue secondary- purpose of a university education is to learn a particular discipline, be it medicine, engineering, etc. The students- have been learning everything up to that point in Sinhala or Tamil. Learning their discipline in their mother tongue will be the easiest thing for them. The solution to this is to teach in Sinhala or Tamil, so it can be learnt in the most efficient manner. Not to lament that the university entrant’s English is poor and therefore we need to start teaching English earlier on.

We are surviving because at least up to the university level we are learning in the best possible way i.e. in our mother tongue. Can our methods be changed to be more efficient? definitely. If, however, one thinks that the answer to this efficient change in the learning process is to substitute English for the mother tongue, it will defeat the very purpose it is trying to overcome. According to Dr. BJCP as he states in his article; the current reforms of 2026 for the learning process for the primary years, centre on the ‘ABCDE’ framework: Attendance, Belongingness, Cleanliness, Discipline and English. Very briefly, as can be seen from the above discussion, if this is the framework that is to be instituted, we should modify it to ABCDEF by adding a F for Failure, for completeness!

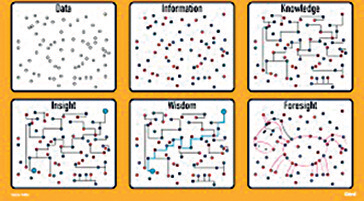

(See Figure 1) The components and evolution of learning: Data, information, knowledge, insight, wisdom, foresight As can be seen from figure 1. data and information remain as discrete points. They do not have interconnections between them. It is these subsequent interconnections that constitute learning. And these happen best through the mother tongue. Once again, this is a fact. Not an opinion. We -all countries- need to learn a second language (foreign tongue) in order to gather information and data from the rest of the world. However, once this data/ information is gathered, the learning needs to happen in our own mother tongue.

Without a doubt English is the most universally spoken language. It is estimated that almost a quarter of the world speaks English as its mother tongue or as a second language. I am not advocating to stop teaching English. Please, teach English as a second language to give a window to the rest of the world. Just do not use it as the mode of learning. Learn English but do not learn in English. All that we will be achieving by learning in English, is to create a nation of professionals that neither know English well nor their subject matter well.

If we are to have any worthwhile educational reforms this should be the starting pivotal point. An education that takes place in one’s mother tongue. Not instituting this and discussing theories of education and learning and proposing reforms, is akin to ‘rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic’. Sadly, this is not some stupendous, revolutionary insight into education /learning. It is what the rest of the world has been doing and what we did till we came under British rule.

Those who were with me in the medical faculty may remember that I asked this question then: Why can’t we be taught in Sinhala? Today, with AI, this should be much easier than what it was 40 years ago.

The editorial of this newspaper has many a time criticised the present government for its lackadaisical attitude towards bringing in the promised ‘system change’. Do this––make mother tongue the medium of education /learning––and the entire system will change.

by Dr. Sumedha S. Amarasekara

Features

Ukraine crisis continuing to highlight worsening ‘Global Disorder’

The world has unhappily arrived at the 4th anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and as could be seen a resolution to the long-bleeding war is nowhere in sight. In fact the crisis has taken a turn for the worse with the Russian political leadership refusing to see the uselessness of its suicidal invasion and the principal power groupings of the West even more tenaciously standing opposed to the invasion.

The world has unhappily arrived at the 4th anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and as could be seen a resolution to the long-bleeding war is nowhere in sight. In fact the crisis has taken a turn for the worse with the Russian political leadership refusing to see the uselessness of its suicidal invasion and the principal power groupings of the West even more tenaciously standing opposed to the invasion.

One fatal consequence of the foregoing trends is relentlessly increasing ‘Global Disorder’ and the heightening possibility of a regional war of the kind that broke out in Europe in the late thirties at the height of Nazi dictator Adolph Hitler’s reckless territorial expansions. Needless to say, that regional war led to the Second World War. As a result, sections of world opinion could not be faulted for believing that another World War is very much at hand unless peace making comes to the fore.

Interestingly, the outbreak of the Second World War coincided with the collapsing of the League of Nations, which was seen as ineffective in the task of fostering and maintaining world law and order and peace. Needless to say, the ‘League’ was supplanted by the UN and the question on the lips of the informed is whether the fate of the ‘League’ would also befall the UN in view of its perceived inability to command any authority worldwide, particularly in the wake of the Ukraine blood-letting.

The latter poser ought to remind the world that its future is gravely at risk, provided there is a consensus among the powers that matter to end the Ukraine crisis by peaceful means. The question also ought to remind the world of the urgency of restoring to the UN system its authority and effectiveness. The spectre of another World War could not be completely warded off unless this challenge is faced and resolved by the world community consensually and peacefully.

It defies comprehension as to why the Russian political leadership insists on prolonging the invasion, particularly considering the prohibitive human costs it is incurring for Russia. There is no sign of Ukraine caving-in to Russian pressure on the battle field and allowing Russia to have its own way and one wonders whether Ukraine is going the way of Afghanistan for Russia. If so the invasion is an abject failure.

The Russian political leadership would do well to go for a negotiated settlement and thereby ensure peace for the Russian people, Ukraine and the rest of Europe. By drawing on the services of the UN for this purpose, Russian political leaders would be restoring to the UN its dignity and rightful position in the affairs of the world.

Russia, meanwhile, would also do well not to depend too much on the Trump administration to find a negotiated end to the crisis. This is in view of the proved unreliability of the Trump government and the noted tendency of President Trump to change his mind on questions of the first importance far too frequently. Against this backdrop the UN would prove the more reliable partner to work with.

While there is no sign of Russia backing down, there are clearly no indications that going forward Russia’s invasion would render its final aims easily attainable either. Both NATO and the EU, for example, are making it amply clear that they would be staunchly standing by Ukraine. That is, Ukraine would be consistently armed and provided for in every relevant respect by these Western formations. Given these organizations’ continuing power it is difficult to see Ukraine being abandoned in the foreseeable future.

Accordingly, the Ukraine war would continue to painfully grind on piling misery on the Ukraine and Russian people. There is clearly nothing in this war worth speaking of for the two peoples concerned and it will be an action of the profoundest humanity for the Russian political leadership to engage in peace talks with its adversaries.

It will be in order for all countries to back a peaceful solution to the Ukraine nightmare considering that a continued commitment to the UN Charter would be in their best interests. On the question of sovereignty alone Ukraine’s rights have been grossly violated by Russia and it is obligatory on the part of every state that cherishes its sovereignty to back Ukraine to the hilt.

Barring a few, most states of the West could be expected to be supportive of Ukraine but the global South presents some complexities which get in the way of it standing by the side of Ukraine without reservations. One factor is economic dependence on Russia and in these instances countries’ national interests could outweigh other considerations on the issue of deciding between Ukraine and Russia. Needless to say, there is no easy way out of such dilemmas.

However, democracies of the South would have no choice but to place principle above self interest and throw in their lot with Ukraine if they are not to escape the charge of duplicity, double talk and double think. The rest of the South, and we have numerous political identities among them, would do well to come together, consult closely and consider as to how they could collectively work towards a peaceful and fair solution in Ukraine.

More broadly, crises such as that in Ukraine, need to be seen by the international community as a challenge to its humanity, since the essential identity of the human being as a peacemaker is being put to the test in these prolonged and dehumanizing wars. Accordingly, what is at stake basically is humankind’s fundamental identity or the continuation of civilization. Put simply, the choice is between humanity and barbarity.

The ‘Swing States’ of the South, such as India, Indonesia, South Africa and to a lesser extent Brazil, are obliged to put their ‘ best foot forward’ in these undertakings of a potentially historic nature. While the humanistic character of their mission needs to be highlighted most, the economic and material costs of these wasting wars, which are felt far and wide, need to be constantly focused on as well.

It is a time to protect humanity and the essential principles of democracy. It is when confronted by the magnitude and scale of these tasks that the vital importance of the UN could come to be appreciated by human kind. This is primarily on account of the multi-dimensional operations of the UN. The latter would prove an ideal companion of the South if and when it plays the role of a true peace maker.

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoReconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoVictor Melder turns 90: Railwayman and bibliophile extraordinary

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoLOVEABLE BUT LETHAL: When four-legged stars remind us of a silent killer

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoVictor, the Friend of the Foreign Press

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoSeeing is believing – the silent scale behind SriLankan’s ground operation

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoBathiya & Santhush make a strategic bet on Colombo

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoBarking up the wrong tree