Features

Joining the Police as a probationary ASP: A dream come true

Excerpted from A Challenge for the Police

by Kingsley Wickramasuriy,

Retired Senior DIG

March 27, 1963 was the dawn of a new era in my life. I had just returned from school around 3.00 pm when I was treated with shouts of Congratulations! by my friends at the boarding house; Neville and Podi Wickremasinghe, and the others at the house. I was throbbing with expectations, eager to hear the news. They produced a copy of “Daily News” carrying the news. The news item read:

Public Service appointments

The Public Service Commission has selected the undermentioned

Candidates for appointment as Probationary Assistant Superintendents of Police.Mr. M.M.K. Mendis (the writer’s previous name) , Mr. M. Shanmugan and Mr. H.G. Gunawardena.

This was the news I was waiting for many moons having put all my energy and hopes towards achieving this goal. My dream as a youngster was to join one of the disciplined services, the Army or the Police.

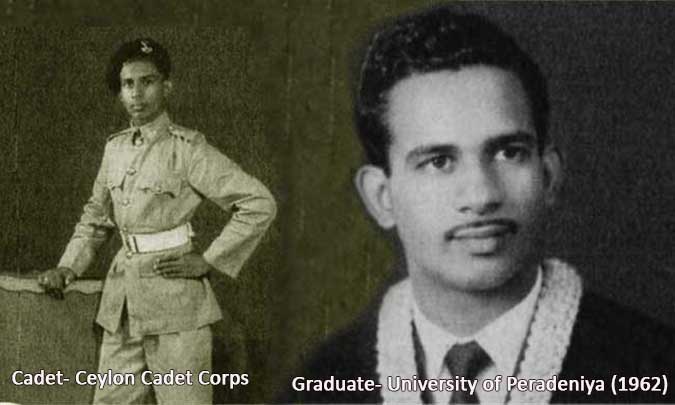

While still a student at school, I joined the School Cadet Platoon at the first available opportunity and participated in all its training activities like parades, camping, 0.22 shooting etc. That instilled discipline in me and eventually, it enthused me to join one of the disciplined Services – the Police or the Army. It was, indeed my training as a cadet of the Ceylon Cadet Corps (CCC) at school that influenced my thinking of joining one of the disciplined services.

It seems that I was carving out my destiny the day I decided to join the Cadet Platoon in school at Kalutara Maha Vidyalaya. The discipline this instilled in me left an indelible mark on my character and consequently my preference for a future career. At first, it was going to be the Army. But my University education, my liking for aesthetic arts which drew me to Dr. Sarathchandra and his drama, and the keen interest that my elder brother took in my advancement and welfare, all had a great influence on changing course midway of the selection of a career from the army to police.

My brother who took on himself the grave responsibility of looking after my education did much research in finding what he deemed a proper career for me. Although the Ceylon Civil Service was the craze at the time that almost every young graduate was fired with the ambition of joining it, my brother found out that a Probationary Assistant Superintendent is an increment ahead of a CCS cadet in salary at the start.

Added to that of course, were the glamour of the uniform plus the power that carried with it and perhaps the prospect of rising through the ranks to the top job as the Inspector-General. He therefore, considered it more prestigious than what the CCS had to offer as a career. To him, it was one of the most coveted jobs that I could get.

His calculations showed that if I were to apply for the post of probationary ASP after doing an honors degree, I would be overage by one year. Therefore, to be qualified to be within the age I had to do a general degree. I was not averse to his idea. He convinced me that that was to be my destiny. I too believed in what he believed. I went along with his thinking and decided to do a General Degree.

This of course allowed me to devote more time to extracurricular activities like drama, boxing, weight lifting etc. Later I also took to writing (Sinhala) poetry in a sudden gush of poetic thoughts overwhelming my imagination in my final year.

After sitting the final examination, a register was opened at the University Senate by the Department of Education for those who would consider a teaching job after graduation to register themselves. By that time vacancies in the police for Probationary ASPs had not been gazetted. I did not even know whether there would be any vacancies for the post. All this while I had taken my chances without any definite indication that there would be any vacancies in the cadre of Probationary ASPs around that time to be within the eligible age limit. So, I registered myself for a teaching post before leaving the University in early April 1962.

Later in the month, I received a letter from the Director of Education, Malay Street, Colombo 2 appointing me as an assistant teacher to Ampara Maha Vidyalaya with effect from May 2, 1962. The letter was dated April 25, 1962. Whilst the appointment was welcome in a way, it was not so welcome considering the sights I had set on securing the post in the police. I wanted to be close to Kandy where I could use the University Library and the Gymnasium in preparation for the examination and the viva-voce that I would have to face in the event there was a vacancy in the police.

I wanted to use the Library for reading and the Gymnasium for physical development to come up with the required knowledge and physical standards for selection to the police. So, I decided to get the appointment changed closer to Kandy. In the meanwhile, St. Anthony’s College, Katugastota advertised a teaching appointment. I applied not being sure whether I could get my appointment changed.

In response, I received a letter form the Principal of St. Anthony’s College dated May 2, 1962, requesting me to accept an appointment from May 21, 1962. In the meanwhile, I also received another letter from the Director of Education canceling the earlier appointment and transferring me to Kengalla Maha Vidyalaya in the Kandy Region. The transfer was effective from May 7, 1962.

Whilst teaching at Kengalla I saw vacancies in the Volunteer Force of the Army being advertised. I applied to join and was selected for a Commission in the Ceylon National Guard of the Ceylon Volunteer Force the same year. I was asked to report to the Headquarters of the Ceylon National Guard at Lower Lake Road, Colombo 2 on October 5, 1962, ready to go for four weeks of training at Diyatalawa, commencing on Oct. 8

When I reported at CNG Headquarters I found a large number of volunteers, officers, and other ranks to be sent for training gathered there. We were sorted into groups and sent by train to Diyatalawa for training. The training was quite strenuous. It included foot drills, physical training, firing practice to tactics. We also had a taste of wining and dining in the Officers’ Mess and training in Mess etiquette.

All told we had a good glimpse of Army-life from what we went through at Diyatalawa. After four weeks of training, we passed out as Second Lieutenants. However, I was to return to Diyatalawa later, this time for the Officer Quality Test as an applicant for a Commission in the Regular Army. I was joined by some who were with me either at Peradeniya University or at training as volunteer Officers like Thilak Ponnamperuma, Dingo Dharmapala, Seneviratne, Walter Ranawana, Daya Wijesekera, Harry Coomaraswamy (class-mate at Royal), Lucky Algama, Lankathilake, and Ranjan Silva.

In the meantime, as if by fortuitous circumstance, the failed coup d’etat of 1962 created three vacancies in the police for the post of Probationary ASPs was gazetted while I was at training at Diyatalawa opening the door for me and the others to join the police as Probationers. My brother who was monitoring the vacancies got me to fill up the application form obtained from the Public Service Commission and had it sent in time.

My referees were Mr. H. Jinadasa C.C.S who was then the Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Education and Broadcasting and Mr. G.P. Samarawickrema, Proctor SC, and JPUM of the Galle Bar. One was a student and the other was a friend of my father. By letter dated December 12, 1962, the PSC granted permission to sit for the examination for recruitment of Probationary ASP. Later, vacancies in the Ceylon Civil Service were also advertised.

I applied to sit for the examination for the selection of candidates and was granted permission to sit for the examination for admission to Administrative Posts in the Public Service including the Ceylon Civil Service. This was on March 6, 1963. But by letter of March 5, 1963, I was asked to present myself at the preliminary interview on March 18. Accordingly, I reported for the interview in Room no 102, First Floor, Galle Face Secretariat, Colombo. Mr. N.Q. Dias, Secretary to the Ministry of Defence, and the Mr. S.A. Dissanayke Inspector-General of Police were two of the members of the interview panel, I could faintly remember.

One of the questions asked was concerning discipline. Discipline is something that was instilled in me by now with cadetting in school and now with Army training. So, I had no difficulty in dealing with that subject. From the emphasis in my answer on discipline, I could see from the response of the Board members that I had made quite an impression on them. Soon after, I was called for the final interview.

The interview was on March 26, 1963 and was held in Room No. 101, of the same Secretariat. This time there was a larger panel consisting of the previous two, the Vice Chancellor of the University of Ceylon, Sir Nicholas Attygalle, and the Chairman of the Public Service Commission. Present for the interview were several candidates amongst who I could remember Rajendra, one of my classmates at Royal College, and Shanmugam who was a senior to me at Peradeniya University.

This time the panel member’s were interested in my book (of Sinhala) poems a copy of which I produced at the interview as one of my achievements and proof of my extra-curricular activities. Their curiosity was about my non-conformist style of poetry writing following the Peradeniya School of Poetry quite popular at the time. From their response, I knew that I had already made my mark and these were just questions for formalities sake.

One thing that struck me was the question Mr. N.Q. Dias asked me. By this time, I had appeared before him for interviews for the selection to the Army having successfully passed the Office Quality Test at Diyatalawa and he appeared keen to get me to join the Army. He wanted to know why I preferred the Police to the Army. My reply was that the police would allow continuing with my interest in cultural activities rather than the cloistered life of the Army in Barracks. He pooh-pooped the idea and appeared to be annoyed.

However, I came out of the room somewhat confident with the gut feeling that I had clinched one of the three vacant posts. So, when I read the ‘Daily News’ of March 27 I knew that I was correct. There I was first in order of merit. I had finally realized my dream; the dream that I had entertained for so

long; the dream that I had strived so hard for with meticulous planning and the dream that I had for almost all my life, thanks to the support and guidance of my brother. That was his dream too. It was his dream more than mine. He too strived hard to make this dream come true. I did not fail him. In the end, both were winners, happy and contented.

Simultaneously, I was called to join the Army by telegram. I received the telegram on April 6, 1963. It read “Please confirm within 48 hours whether you are willing to accept an appointment in the Army in the rank of the second lieutenant”. The sender was the Commander of the Army. I politely turned down the offer.

The next thing I did was to send my letter of resignation from my post of Assistant Teacher to the Assistant Director of Education for the Central Region in Kandy. This I did on March 27, 1963. I had to give a month’s notice to get myself released. At the time of my resignation, I was an assistant teacher attached to Kegalle Maha Vidylaya drawing a salary of Rs. 2,700.00 per annum and allowances. I served in this capacity from May 7, 1962, to April 30, 1963. Then on April 5, 1963, 1 wrote to the Commanding Officer of the Ceylon Volunteer Force resigning from my Commission.

In the meanwhile, I received the letter of appointment from the Public Service Commission dated April 3, 1963. According to the stipulated conditions of the letter of appointment the post carried a salary scale of Rs. 4,440.00 per annum with 11 annual increments of Rs.360.00 and 10 annual increments of Rs. 480.00 reaching a maximum of Rs. 13,200.00. There were also two efficiency bars before reaching the annual salary scales of Rs.8,400.00 and 11,760.00.

I was also required to get through the stipulated Sinhala proficiency examination and other departmental examinations before being confirmed under Administrative Regulation 121. These were some of the stipulated conditions among several others like the declaration of assets, being medically fit, a contribution of four percent of the salary to the Widows & Orphans Fund, etc.

The letter was duly acknowledged. This was followed by a letter from the Deputy Inspector-General in charge of Administration asking me to report to the Acting Director of the Police Training School at Katukurunda, Kalutara before 6.00 pm on May 1, 1963. This was to be the dawn of a new chapter in my life. I was eagerly waiting for it to start.

( To be continued)

Features

Excellent Budget by AKD, NPP Inexperience is the Government’s Enemy

by Rajan Philips

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake has delivered an excellent first budget. It could easily be described as the best budget so far this century and presented in the most dire economic circumstances in Sri Lanka’s modern history. Following his consummate performance in parliament, the President waded into a post-budget forum and joined the country’s economic experts to “dissect new Govt’s maiden budget,” as headlined by the Daily FT, one of the sponsors of the event. Whether one agrees with him or not, there is no question that AKD has been listening to those who knows the subject, has diligently done his homework on the budget file, and knows what he is doing,.

The problem he faces is that he cannot be doing homework on every file for the entire government, and he must find a way to quickly address the collective inexperience of his cabinet. He should not let this inexperience become the enemy that kills the government from within. Hopefully, he will find a way to address this within the framework of the budget and in the delegation of ministerial responsibilities for its implementation.

Somewhere in the budget, the President refers to economic decentralization, to deconcentrate the top heavy Western Province. Unfortunately, the corollary of political decentralization could not find its place in the text. Equally important, the President should also pay attention to ‘cabinet federalisation’ (AJ Wilson’s description of one of DS Senanayake’s quite a few master traits), and more so as he moves ahead to implement the budget proposals.

Ultimately, the success of the budget will be measured in political terms. Read, electoral terms. AKD’s and NPP’s detractors will be winding themselves for political wrestling in the local and later the provincial council elections. The NPP could be expected to hold its ground, but not necessarily all two-thirds of it. It should not at all be strange if the NPP gains ground in the North and East even as it loses some of it in the South. To keep the inevitable losses to the minimum, the government must eschew any and all complacency, which, modifying Mao’s famous Redbook take on it, could be described as the enemy of elections.

Geopolitically, paraphrasing the French Marxist Regis Debray, the NPP government must have its overhead antennas fully alert, but its feet firmly planted on the ground in Sri Lanka. The government cannot avoid being distracted by the global tumults that Donald Trump is creating day in and day out. There will be ripples, even waves, around Sri Lanka depending on what the Modi government decides to do in India to harmonize with the Trump Administration in Washington. Even so, the government’s primary preoccupation in the context of the turmoil in America should be to protect for as long as possible Sri Lanka’s exports to the US which are significant for Sri Lanka’s forex earnings.

At the same time, and consistent with the budget objectives, even as it diversifies its exports the government must diversify its importers. For the next four years, as Trump unfolds his madness, there will be responsive realignments in the Global North even as there will be reconsolidations in the Global South. The NPP government will have to navigate Sri Lanka through these currents without being smothered by them.

There are of course the self-proclaimed Rajapaksa nationalists who want to hitch their broken political wagons in Sri Lanka to the passing hegemon in America. They are in fact ethno-narcissists just like – but writ-small – the racial narcissist that Trump is. Ridiculous as these forces and their politics might seem, indeed as they are, the government should not underestimate their potential to do harm even by accident. Look at Bangladesh to see how political fortunes can dissipate fast, even though the NPP government is in no way comparable to Sheikh Hasina’s rotten government. The eternal home truth is the quick rise and the quicker fall of Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

Setting the Budget Context

The budget speech outlines as its backdrop the 2022 economic crisis that has now become the Rajapaksa era legacy, and as its context the overwhelming verdict of the people in the 2024 presidential and parliamentary elections. In this context, the President calls the budget both “historic” and “challenging,” because the government has to not only lay the foundation for fulfilling the people’s aspirations, but also to dispel “the wrongful picture (of us) created by the myths and malicious political propaganda against our economic policy and vision.” “We have succeeded in that,” the President asserted.

The government has proved its expectant critics wrong and stabilized the economy. All the indicators confirm that – the relatively stable exchange rate at one USD for LKR 300, and not LKR 400 as recklessly scare mongered; the lowering of the Treasury bill rate (8.8%) and getting inflation under control; forex reserves rising past USD six billion; finalizing agreements over debt-restructuring; and most of all keeping essential goods available and avoiding queues. In fairness, the credit for starting the process of economic stabilization belongs to Ranil Wickremesinghe, but post-election expectations in political circles have been that things will start to unravel due to NPP’s inexperience and even incompetence. That did not happen, and President AKD and the NPP government are justified in claiming credit for it.

Mr. Wickremesinghe may have even fancied that another economic crisis this time under an NPP government would give him a second kick at the can of power. No such luck. RW is now part of a team of exes – former ministers and presidents including Maithripala Sirisena – trying to figure out a way to stay relevant in today’s politics. Looking at this aging crowd outside parliament and its slightly younger version in the opposition within parliament, the NPP might fancy its chances of retaining power for more than one cycle of elections. But what the NPP has to contend with ultimately will not be ill equipped politicians but a frustrated electorate.

Apart from President AKD’s versatile feats, the NPP government has little to show to keep the people contented. Recurring rice shortage, the shortfall in coconuts, and the power outage blamed on a monkey tripping off a transformer have certainly taken the shine off the government. Looked from the other end, rice, coconuts and the power outage seem to the only shortcomings that the government is being picked on by media pundits and the political class. But what should concern the NPP government is that any one of them (rice, coconut or power), all of them together, or any similar shortages or failures, are enough to rile the people and bring down a government. Not long ago, it was called aragalaya.

Budget as Political Reset

The budget speech lays down the principles underlying the government’s approach to the economy: sectoral growth sustained by participation and even distribution on the supply side; and balancing roles for the market and the government on the demand side. A GDP growth rate of 5% is targeted for the medium term, predicated on a strong export sector performance while maintaining price stability and ensuring social welfare. Promoting investments, leveraging logistics, revamping tourism, digital transformation of the economy, and unleashing SME potentials through new credit structures are highlighted as the main growth poles. Allocations for health, education, food security, and social benefits are intended to rebuild and strengthen country’s social welfare system.

There is emphasis on Regional Development, including the assurance of special programmes for the Eastern Province, the Malayaga Tamils, and the Northern Province, but there is no mention of Provincial Councils and Local Government bodies and their agency roles in regional development. Regional industrial zones are identified including the promotion of Chemical Manufacturing in Paranthan, KKS and Mankulam in the Northern Province, Galle in the South and Trincomalee in the East. If some of them were to materialize the North and East might be seeing state sponsored industrial activity after more than 70 years when GG Ponnamabalam was Minister of Industries and Fisheries.

Auto Parts and Rubber Products manufacturing is also identified for promotion through industrial zones. What is not clearly indicated is whether new regional industrial initiatives will be tied to the export sector without which they may not be viable, as past experience has shown. Also, on the export front there is no identification of specific products and target markets to match the significant export sector growth that is being championed. Generally, for industries, there should be guardrails for minimizing and mitigating adverse environmental effects.

The budget rightly focuses on the modernization of public transport. Specific projects are identified for bus transport in Colombo and for the rail sector, including the revamping and the extension of the KV Line, multi-modal transport terminal in Kandy, and the expansion of the Thambuththegama Railway Station to function as a hub for transporting agricultural products. Large scale transport projects and rail transport are invariably the responsibility of the central government, but bus transport operations including those in Colombo and Kandy are better assigned to provincial and even larger municipal governments.

The budget provides for settling the legacy debt of the Sri Lankan Airlines (SLA) in the hope that SLA would hereafter become a viable enterprise. For other SOEs, the budget is proposing the setting up of a Holding Company again with the hope of revitalizing the mostly under-performing State Owned Enterprises (SOEs). Whether this approach is motivated by patriotic sentiments or political calculations, there is little support for it from past experience, except for enterprises in the crucial servicing and energy sectors.

The budget gets quite specific in its proposals for the agricultural and food sectors, especially rice and coconuts. At long last, there is official admission at the highest level that there is no data and information system for the “entire value chain” from paddy production to rice consumption. There is no immediate solution to this except the assurance to find one through the ADB funded “Food Security Livelihood Emergency Assistance Project” and a related World Bank project.

Coconuts are easy to count and difficult to hide. Some 4,500 million nuts are the projected demand for 2030, with 2,700 for the coconut industry and 1,800 for household consumption – at one per household per day. The problem is with production and the budget is allocating money for high yielding seedlings to be used in a new Northern Coconut Triangle extending from the coconut rich Northwestern Province, recommended by the Coconut Research Institute and mirror imaging the long established Southern Coconut Triangle. Better later than never, even when it comes to nuts.

All in all, the budget provides a good framework for the NPP government to reset its political road map. To succeed, the resetting must involve delegations at the ministerial level and following through to local communities and political grassroots. Equally important will be the medium in between, and the challenge to the NPP government is in resurrecting and using the currently defunct provincial and local government agencies.

Features

The Murder of a Journalist

By Anura Gunasekera

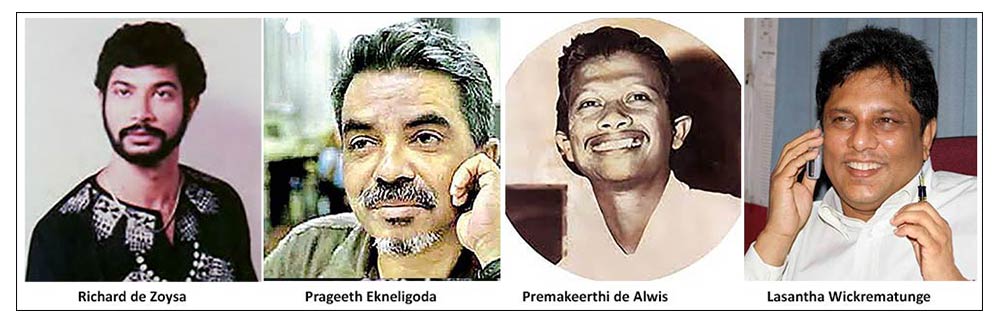

Commencing with Premakeerthi de Alwis in 1986 and concluding with Lasantha Wickrematunge in 2009, 40 accredited Sri Lankan journalists and media personnel, 31 of them of Tamil, have been murdered or died violently. Of these, 31 occurred between April 2004 and March 2009, during the Mahinda Rajapaksa tenure, initially as Prime Minister and then as President. His younger brother Gotabaya, later president himself, was the Defence Secretary of the country from 2005 to 2015.

During the above period, apart from those killed, many were abducted, assaulted and /or tortured, and intimidated in various other ways. A few left the country in fear of their lives. Most, if not all of those journalists, unsurprisingly, had been vocal critics of the government. With the defeat of the Rajapakse government in 2015, all harassment of journalists ceased, abruptly.

Of the above killings, those of Lasantha Wickrematunge (LW) and that of Richard de Zoysa in 1990, as well as the disappearance of Prageeth Ekneligoda in 2010 are, for a variety of reasons, not least the international outrage and condemnation, considered the most prominent. The most disturbing commonality across all these crimes is that none have been comprehensively investigated and the perpetrators punished.

In fact, despite pointers regarding the identity of the masterminds- circumstantial but compelling – and the very public nature of most of the actual incidents themselves, investigations have been either obstructed or stifled, through intimidation of potential witnesses, misleading autopsies, the enthusiastic pursuit of patently false lines of investigation, deliberately disingenuous official statements and, not infrequently, the suppression or disappearance of physical evidence.

The murder of Richard de Zoysa is again in the limelight on account of the recent film, “Rani”, although any hope of the crime being solved is almost zero. The murder of LW has been publicly profiled in the last few weeks, due to the order for the discharge, by the Attorney General (AG), of three suspects linked to events consequent to the murder, on the grounds of insufficient evidence.

Since the murder of LW, four successive governments have assured the country and the international community, that the case would be comprehensively investigated and those responsible punished. The slain Lasantha Wickrematunge had become an international metaphor for delayed justice. The present NPP government, led by president Anura Kumara Dissanayake, made the investigation of previously unsolved crimes, including that of Lasantha’s murder, and the cleansing of corrupt government systems, a cornerstone of its election manifesto. The sweeping victory of the NPP at the recent general elections was largely due to the faith that the electors placed in those promises.

Why is the case of Lasantha Wickrematunge so important?

Investigative Journalists play a vital role in maintaining a free and open society, by providing the public with critical information, holding power to account and exposing corruption and injustice. In that context, LW played a major role through his paper, “The Sunday Leader” which, week after week, exposed the massive corruption within the Rajapaksa regime, citing specific transactions and quite often linking acts of malfeasance to then President Mahinda Rajapaksa, his brother and Defence Secretary Gotabaya, or to close associates of the Rajapaksa family and the regime.

LW’s silence was worth more to the Rajapaksa family in particular, than to anybody else in the country. In fact, LW’s murder was apparently preceded by an unsuccessful attempt, in 2007, by Mahinda Rajapaksa himself, to broker the sale of the paper to an investor of his choice, the offer being made to Lal, LW’s brother (Page 234- Unbowed and Unafraid- Raine Wickrematunge). The only possible reason for a president of a country to personally seek the divestment of ownership of an outspoken newspaper, is control of its narrative content and direction.

Two years later Lasantha’s assassination paved the way for the exercise of this option.

In Sept 2012, businessman and alleged Rajapakse associate, Asanga Seneviratne, many of whose property development and investment deals had been criticized at various times by the “Leader”, bought a 72% stake in the “Leader” and its sister newspaper, “Iruresa”. In the same month Frederica Jansz, then editor of the “Leader” and long-time colleague of LW, was summarily dismissed from her position. In May 2015 the “Leader”, now under a decidedly Rajapaksa-friendly dispensation, tendered an unconditional apology to Gotabaya Rajapksa for a series of articles it had run, during LW’s tenure as editor, on the indisputably questionable method of purchase of MiG-27 aircraft from Ukraine, for the Sri Lanka Air Force. Udayanga Weeratunga, relative of the Rajapaksa family, as then Sri Lanka’s ambassador to Ukraine, allegedly played a major role in facilitating the said transaction. According to Ahimsa, LW’s daughter, LW was on the verge of exposing the highly complex and sordid details of the deal in entirety, when he was murdered (The MiG deal; Why My Father Had To Die- Groundviews-01/08/21).

The above is just one of the hundreds of expose’s featured by LW and he very rarely got it wrong. Very few other journalists in recent decades – the late Victor Ivan was one other- so courageously and in such minute detail, addressed the sins of those in power as LW did. They were issues that many journalists avoided, a self-regulation on truthful journalism brought about as a conditioned survival mechanism, in response to the brutal repression of those who dared to write the truth about power.

LW’s last writing- “Then They Came For Me”– published posthumously and now a classic of Asian journalism, was a chillingly prophetic prediction of his own death, pointing an accusatory finger at his erstwhile friend, then president Mahinda Rajapaksa.

The death of any human being diminishes society but the death of a fearless journalist, who holds a mirror to the foibles of society and power, diminishes our world in a special way; especially a world such as ours where leaders, irrespective of political colour, have proved to be treacherous, unreliable, corrupt, mercenary and nepotistic.

On the 27th of January, Parinda Ranasinghe Jr, Attorney General (AG) of Sri Lanka, ordered the release – citing lack of evidence to proceed with indictments – of Ananda Udalagama, implicated in the abduction in August 2009 of Karunaratne Dias, LW’s driver, and DIG Prasanna Nanayakkara and Sub-inspector Sugathapala, both implicated in the disappearance of a notebook recovered from LW’s vehicle after his murder. Consequent to immediate and widespread criticism and physical demonstrations against this order, it has since been rescinded.

In this episode the primary, indisputable principle, is that it is entirely at the AG’s discretion, to decide whether or not to charge a suspect, taking in to account the validity of admissible evidence available, and the prospect of securing a conviction. The political body has no right suggest a review of such a decision, or to compel the AG to consider such a review, irrespective of the importance of the case. At the same time it is also assumed that the AG and his department will carry out their duties impartially, irrespective of past loyalties – if any – and current personal prejudices, especially in relation to sensational cases involving those previously and currently in power.

Assuming that the release order was issued after a comprehensive analysis of the available evidence, the subsequent reversal is baffling, to say the least. Is it that the AG, or the legal officers responsible, consequent to a re-assessment of available material, suddenly realized that they had a made a serious error of judgment? Or did the AG’s department cave in to political and public pressure and decide to change its decision?

If the AG had braved both public and political displeasure and held fast to the original decision, it would have been perfectly acceptable and even commendable. However, it is now being reported in responsible mainstream newspapers, that the rescinding of the original decision is a response to a request by the Criminal Investigation Department (CID), to give it more time to act on the AG’s order, on account of the controversy surrounding the issue. The official version now appears to be that what is now in place is a suspension of the original decision, and not a reversal.

In the meantime, Ahimsa, through her publicized letter of February 14 to Anura Meddegoda, President of the Bar Association of Sri Lanka, has censured him for his hypocritical support of the AG and his position in this episode. She has supported her position by reference to Meddegoda’s protest against a similar order by the AG, under very similar circumstances, when it involved the murder of one Indika Prasad, allegedly by members of the Special Task Force. The interests of the victim’s wife were represented by Meddegoda.

Ahimsa has condemned the AG’s position in this matter, in the said letter citing seemingly convincing evidence available against the three suspects named earlier. She has even called for the impeachment of the AG, on the grounds that in ordering the discharge of the suspects, he has deliberately chosen to ignore vital evidence.

For an ordinary citizen such as the writer, with only a minimal understanding of criminal law, an analysis of the legal validity of the AG’s management of the case in question is not possible. But, still, to the writer and to several million other citizens who helped to bring the NPP in to power, the delivery of justice in matters of public corruption, politically motivated murders and similar crimes, are issues of supreme importance.

Fearless journalists such as Lasantha Wickrematunge paid with their lives for their reportage and public exposure of the crimes of the politically powerful. The justice for such crimes is owed, not only to the family members of the slain, but to the nation itself. It ceased to be a private, Wickrematunge family project a long time ago.

President AKD has steadfastly maintained that his regime will not interfere with ongoing legal processes, unlike previous regimes which seemed to often guide the hand of the law, in cases which featured those in power, unfavourably. However, what may be prudent and necessary, if justice is to be finally done, is intervention and course correction at critical stages, to ensure that public officers entrusted with relevant responsibilities do not lose sight of both the principle and the objective.

Features

My Dog Tosca

My Dog Tosca

Michael Patrick O’Leary

We did not delude ourselves that we owned her. My title is a reference to JR Ackerley’s memoir, My Dog Tulip. JR Ackerley was adistinguished British man of letters. His dog was, in reality, a German Shepherd called Queenie. My Dog Tulip is an account of their sixteen-year companionship, as well as a meditation on the peculiarity of all relationships.

When we first moved to Sri Lanka in 2002, we rented a large plantation bungalow on the outskirts of Bandarawela in Uva province in the hill country. There were four huge bedrooms each with a large bathroom containing a deep bath with cast iron ball and claw feet. We strongly suspected that the house was haunted, but that is material for another article.

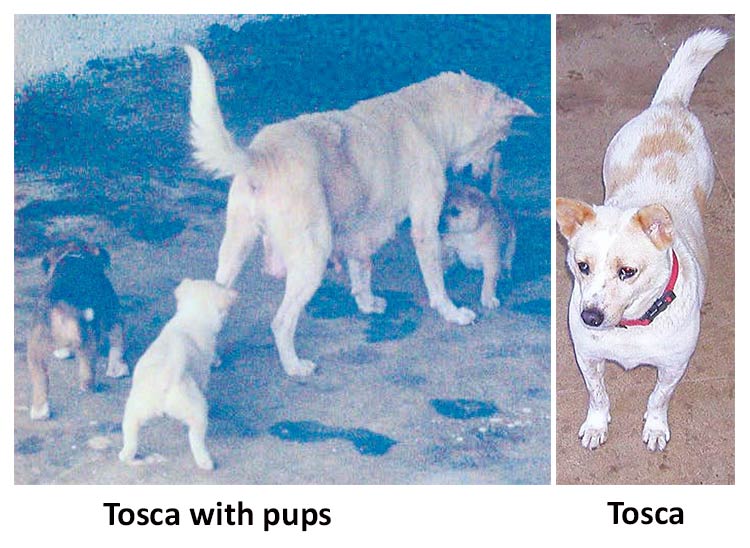

I noticed Tosca on my way to the kade. She had a horrible abscess hanging out of one eye but had a very benign expression. Dogs are not supposed to smile but she seemed to do so, beatifically. She seemed to take to us and, somewhat nervously, started approaching our house. One night we noticed her sleeping in a drain near the house and she was not alone. A female companion, who later became known as Daisy, was huddling with her for warmth.

We gradually adopted these two as our own, although we could not delude ourselves that we owned them.

Unfortunately, Tosca, in particular, became prey to the rampaging males of the area and was often subjected to gang-rape. One rather timid fellow we named The Suitor, was in flagrante when Hendrick, a disreputable one-eyed old roué of an ageing rock star who lived on the estate and considered he had prior rights, urinated on The Suitor in mid-coitus. Some people pay good money for that in Moscow hotels (allegedly).

The result of all this male attention was a litter of pups. One very small black and tan one died soon. Two of them were later found homes and given the names Lucky (a bad choice) and Sando (I had called him Tufton Bufton). More of those later. Silky remained with us and moved to a new with us.

When the pups were first born, Tosca was perhaps not an ideal mother. One got the feeling that she thought a different kind of life was her due. She remained rather plump after the pregnancy and she reminded me of one of those 1950s blonde pneumatic movie stars like Mamie van Doren or Jayne Mansfield (I’m showing my age here, readers). She would often abandon the pups and come to hide from them with us in the sit-out around the back of the house. The little monsters always managed to find her and squawk and bite and scratch at her abused undercarriage.

Luckily, we knew a good vet and she was able to perform surgery at our home to remove the abscess from the eye and to sterilise Tosca. A lot of veterinary attention was needed. On one occasion, she seemed very ill and was hiding in the bushes. The vet thought she might have been poisoned. We took her to the Veterinary Faculty at Peradeniya University in Kandy, where she was admitted for observation. Tosca loved motor travel. In fact, she demanded to get in the car whenever we went shopping. Children looked in and told their parents there was a beautiful dog in the car. She serenely took such compliments as her due. If she saw another dog passing by she would bark at it imperiously.

The journey to Peradeniya was not too difficult, but Tosca clearly did not think the accommodation at the veterinary faculty was up to the standards to which she had become accustomed. When we went to collect her after six days she was very huffy and walked briskly to a white car and demanded to be let in. Unfortunately, it was someone else’s car.

When we moved to our own house, Tosca, Daisy, Hendrick and Silky came with us. The intricate social dynamics of this ménage, particularly the antics of Tosca and Daisy in their lesbian love nest, must be the subject for another article (or scholarly thesis or porn movie). We retrieved Sando from his adoptive parents. He was no longer the grumpy fellow we had known before. He was now a perfect gentleman, which caused Silky to bully him mercilessly.

Tosca continued to enjoy her status as motor-mutt with the bonus of long walks through the tea estate and mud-baths, the dirtier the better. She is no longer with us. Like most street dogs, she once had a home with humans who abandoned her. She endured with dignity. She survived a long time after being diagnosed with mouth cancer. I am not ashamed of appearing sentimental when I say that I hope we added something to her life.

In the New York Review of Books, Catherine Schine reviewed an animated movie version of JR Ackerley’s memoir My Dog Tulip.

“What strained and anxious lives dogs must lead, so emotionally involved in the world of men, whose affections they strive endlessly to secure, whose authority they are expected unquestionably to obey, and whose mind they never can do more than imperfectly reach and comprehend. Stupidly loved, stupidly hated, acquired without thought, reared and ruled without understanding, passed on or ‘put to sleep’ without care, did they, I wondered, these descendants of the creatures who, thousands of years ago in the primeval forests, laid siege to the heart of man, took him under their protection, tried to tame him, and failed—did they suffer from headaches?”

(“Michael Patrick O’Leary is an Irish citizen who has lived in Sri Lanka with his Sri Lankan wife since since 2002.

More of his writing can be found on Substack. Please subscribe . It’s free! https://moleary.substack.com)

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoDon’t betray baiyas who voted you into power for lack of better alternative: a helpful warning to NPP – II

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoCommercial High Court orders AASSL to pay Rs 176 mn for unilateral termination of contract

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoSri Lanka face Australia in Masters World Cup semi-final today

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoTwo films and comments

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoUSAID and NGOS under siege

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoDoing it in the Philippines…

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoCourtroom shooting: Police admit serious security lapses

-

Midweek Review5 days ago

Midweek Review5 days agoImpact of US policy shift on Sri Lanka