Opinion

Is persistent mudslinging solution to our problems?

By Dr Upul Wijayawardhana

It is no secret that the JVP/NPP government came to power mostly by slinging mud at their opponents, no doubt justified to some extent. There were gross exaggerations, claiming that nothing positive has happened since independence and tarring all politicians with the brush of corruption! It looks as if it wants to remain in power using the same tactic probably because it finds it difficult to keep to some of the promises it made to gain power. The sheer eloquence displayed by the president during the election campaigns seem to be coming to haunt him. On many things, which he stated could be reversed by a stroke of a pen are still pending and sceptics are questioning whether the president has misplaced the pen, just like the former speaker has misplaced his academic certificates!

Distortions continue to be the order of the day and as mentioned in the editorial “From ‘chits’ to ‘lists’ (The Island, 1 March), lists are being used to attack opponents, some of whom have already received ‘political punishment’ from the voters. What is worse are the unfair comparisons made, well exemplified by the list of expenses for foreign travel by presidents. The government made the crucial mistake of not limiting it to former presidents but in an attempt to create a whiter-than-white image of the president, it added unbelievably low cost to the present president’s three foreign trips. It is very likely that the expenses for the former presidents were for the entourage whereas for the present president, it was only for himself! Part of the low cost was attributed to the president receiving free tickets for two trips. I am sure if the tickets were provided by the inviting governments, it would have been stated as such and one must assume that they were from other sources, which raises further questions; who are these generous guys and why did they do it? Reminds one of the saying “There is nothing called a free lunch!”

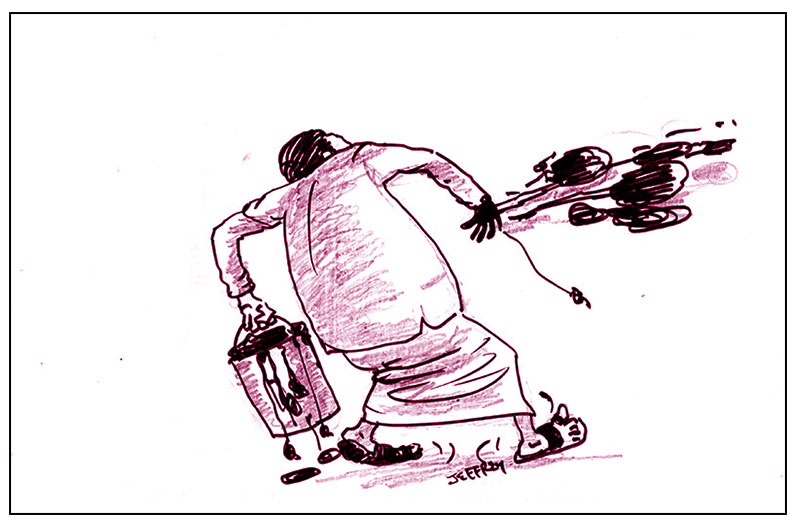

More importantly, one fervently hopes that the reverse does not happen; from going from ‘lists’ to ‘chits’ again, which would be a disaster. It was a disaster that cost thousands of lives and remembered with trepidation by those who were lucky enough to survive. A colleague of mine has forwarded a photograph of one of these notorious ‘chits’ sent during the second JVP uprising, which is in circulation in social media now, and called me later to have a chat. I was taken aback when he told me that he had them pasted daily on his door, as he worked part-time for the army. He had torn them away but on learning this, his superior medical officer had advised him to leave the country, for the sake of his young family, which he did. He worked in New Zealand a year before coming to the UK. Do hope this does not happen again but the video circulating showing a party-man advising a villager not to post adverse comments on the government, raises the possibility that ‘chits’ may raise its ugly head again!

I am not sure whether it was the president who stated that fuel prices could be brought down immediately by cutting off commission charged by the previous minister but the widely anticipated fuel price reduction never materialised. Whoever that made the accusation owes an apology to the previous minister.

However, I am sure the president gave repeated assurances that Arjuna Mahendran would be brought back to stand trial for the Bond Scam. He told cheering audiences that he could do it with a stroke of his pen, in spite former president Sirisena claiming that he placed more than 2,500 signatures for this purpose. It did not succeed and, instead, Mahendran dared by publishing two letters in The Island, giving his full postal address in Singapore, the moment Ranil became president. He would not have done so without knowing that he would be protected. It is a pity AKD did not appraise himself of facts before giving categorical assurances. What is the government’s position now? “We have encountered some legal difficulties but don’t worry, we will try him in absentia” according to the cabinet spokesman, which is hilarious!

The Mahendran episode raises another interesting question. There are droves who sing hosannas for Singapore and Lee Kuan Yew. Whilst not trying to belittle what LKY achieved for Singapore, I have always questioned whether he is a true democrat. He was far from it and what he did to his opponents is conveniently forgotten because of the massive transformation he engineered. Coming to the present, much is made of Singapore’s anti-corruption measures. There are regular reports of politicians being jailed for corruption and many contend that Singapore thrives as it has eradicated corruption. This raises the question why it is refusing to extradite a Singapore citizen who is charged with corruption? Is it that Singapore’s anti-corruption drive operates only when it is an internal matter? Is it that Singapore does not care when one of its citizens takes on an extremely responsible job in a foreign country and indulges in corrupt activities? Is this not the height of hypocrisy?

Although Gotabaya is hauled over the coals for making the country bankrupt, the rot started with Yahapalanaya and the Bond Scam is one of the major factors. Mahendran, who lacked any suitable experience, was imported on false pretences by Ranil but, interestingly the Handunnetti COPE report did not apportion any blame to Ranil. As all investigations laid the blame on Mahendran, who left the country to attend a wedding according to Ranil, not being able to bring him back is a gross injustice. Of course, the government spokesman had a wonderful solution; “As it is his friend, Ranil should bring him back. Then we will prosecute him”! If Mahendran saga is not resolved, it would be a shame for our government and would tarnish the reputation of Singapore, as well.

It is high time the government stopped slinging mud at opponents and start taking actions to solve the problems affecting the masses, the most important being the cost of living.

Opinion

Trump tariffs and their effect on world trade and economy with particular reference to Sri Lanka – Part IV

(Continued from yesterday)

Critique of the International Trade System

President Trump’s tariffs have also highlighted fundamental inequities in the international trade and financial architecture that governs economic relations between wealthy and developing nations.

The World Trade Organization, theoretically designed to provide a rules-based trading system that benefits all members, has proven largely powerless to prevent unilateral actions by powerful economies like the United States. While China has urged the WTO to investigate President Trump’s tariffs as violations of the “most favoured nation” principle that forms the bedrock of the multilateral trading system, the organization lacks effective enforcement mechanisms against major powers.

Similarly, international financial institutions like the IMF have failed to adequately account for trade shocks in their lending programmes and debt sustainability analyses. As discussed earlier, the IMF’s approach to Sri Lanka’s debt restructuring focused primarily on fiscal consolidation while paying insufficient attention to the country’s

Page 17 of 29

structural trade deficit and vulnerability to external shocks. When Trump’s tariffs suddenly reduce Sri Lanka’s export earnings, the IMF program offers no automatic adjustment mechanisms to accommodate this changed reality.

This situation stands in stark contrast to historical examples of more equitable treatment of indebted nations. The London Debt Agreement of 1953, which restructured West Germany’s external debts, explicitly linked repayment obligations to the country’s trade performance and capped debt service at a sustainable percentage of export earnings. Such an approach recognised the fundamental importance of trade capacity to debt sustainability, a recognition largely absent from contemporary debt restructuring frameworks.

The tariff shock thus reveals not merely technical flaws in trade policy but deeper structural inequities in how the global economic system distributes risks, rewards, and adjustment costs between wealthy and developing nations. While powerful economies can unilaterally reshape trading relationships to serve their domestic political objectives, developing countries must largely accept these changes as given constraints and bear disproportionate costs of adjustment.

Potential Reshaping of Global Trade Patterns

Looking beyond the immediate disruption, President Trump’s tariffs may accelerate several longer-term shifts in global trade patterns with significant implications for developing economies.

First, we may see accelerated regionalisation of trade as countries seek to reduce vulnerability to U.S. policy shifts. Asian economies may deepen integration through mechanisms like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), while African countries might accelerate the implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). These regional arrangements could provide alternative markets for exports previously destined for the United States, though the transition would be neither quick nor painless.

Second, China’s role as both a market and investor for developing economies may expand further. As U.S. tariffs effectively close off portions of its market, developing countries may look more intensively toward China as an export destination and source of development finance. This shift would have significant geopolitical implications, potentially accelerating the fragmentation of the global economy into competing blocs centred around major powers.

Page 18 of 29

Third, some production may relocate to avoid tariffs, creating winners and losers among developing countries. Nations with lower tariff rates or special exemptions could see increased investment as firms restructure supply chains to minimise trade costs. This dynamic could intensify competition among developing countries for foreign investment, potentially triggering a “race to the bottom” on labour and environmental standards.

Fourth, there may be renewed interest in domestic market development and South-South trade as alternatives to excessive dependence on wealthy consumer markets. While the limited purchasing power in many developing countries constrains this option in the short term, over time it could lead to more balanced and resilient development models.

These potential shifts suggest that President Trump’s tariffs may represent not merely a temporary disruption but a catalyst for more fundamental reconfiguration of global trade patterns. For developing economies like Sri Lanka, navigating this changing landscape will require strategic foresight, policy innovation, and international cooperation to ensure that the emerging trade architecture better serves their development needs than the system currently being disrupted.

POTENTIAL MITIGATION STRATEGIES FOR SRI LANKA

Faced with the severe economic challenge posed by Trump’s 44% tariff, Sri Lanka must develop a comprehensive response strategy that addresses both immediate threats and longer-term structural vulnerabilities. This section explores potential approaches at different time horizons, from emergency measures to fundamental economic reorientation.

Short-term Responses

In the immediate term, Sri Lanka’s government and private sector must focus on crisis management to minimise damage to export industries and protect vulnerable workers. Several approaches warrant consideration.

Government Support for Affected Industries

The Sri Lankan government could implement targeted support measures for export sectors most affected by the tariffs, particularly the textile and apparel industry. These might include temporary tax relief, subsidised credit facilities, or reduced

Page 19 of 29

utility rates for export-oriented manufacturers. Such measures could help companies weather the initial shock while they develop adaptation strategies.

However, Sri Lanka’s fiscal constraints present a significant challenge to implementing such support. The country’s IMF programme imposes strict limits on government spending and deficit targets, while tax increases have been a central component of the economic stabilisation strategy. Any support measures would therefore need to be carefully designed to remain within these constraints or negotiated as exceptions with the IMF based on the external nature of the shock.

One potential approach would be to reallocate existing resources rather than expanding overall spending. For instance, funds previously earmarked for export promotion in the U.S. market, if any, could be redirected toward supporting market diversification efforts or providing temporary relief to affected companies.

Diplomatic Engagement with the United States

Sri Lanka should pursue active diplomatic engagement with the United States to seek modifications to the tariff regime. While the country’s limited economic leverage makes a complete exemption unlikely, there may be opportunities to negotiate targeted relief for specific product categories or to secure technical assistance for adjustment.

The Sri Lankan government could emphasise several arguments in these discussions, the disproportionate impact of the tariffs on a country still recovering from economic crisis, the potential humanitarian consequences of mass unemployment in the textile sector, and the strategic importance of economic stability in Sri Lanka for regional security in the Indian Ocean.

One of the most compelling arguments Sri Lanka can make is the need to move beyond narrow fixation on the trade balance and instead consider a broader current account. While Sri Lanka may show a surplus in goods trade with the U.S., that figure is only a part of the story. Our economy is deeply integrated with U.S. linked services. We pay for American banking and credit card services, subscribe to streaming platforms like Netflix and Amazon, purchase of software and apps from Apple and Google, remit interest payment on loans from international banks, bond holders and multilateral institutions, and spend on tourism and education. When all of these outflows are taken into account, the so called “imbalance” is far more nuanced if not fully offset. This is why a fair and modern economic analysist must consider the full current account, not just goods trade in isolation.

Page 20 of 29

Engagement should occur through multiple channels, including direct bilateral discussions, multilateral forums like the WTO, and coordination with other affected developing countries to amplify collective concerns. Sri Lanka might also leverage its relationships with international financial institutions like the World Bank and IMF, which could highlight the risks the tariffs pose to the country’s economic recovery program.

Emergency Economic Measures

If the full impact of the tariffs materializes, Sri Lanka may need to implement emergency economic measures to maintain macroeconomic stability. These could include temporary foreign exchange controls to prioritize essential imports, accelerated disbursement of already-committed international financial support, or emergency borrowing from friendly countries or international institutions.

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka might need to adjust monetary policy to respond to potential currency pressures resulting from reduced export earnings. However, any such adjustments would need to be balanced against inflation concerns, which remain sensitive following the recent crisis.

Social Protection for Affected Workers

Protecting workers who lose jobs or face reduced hours due to the tariff impact should be a priority. The government could expand existing social safety net programs to specifically target affected textile workers, potentially with support from international donors or development agencies.

Measures might include temporary unemployment benefits, retraining programmess for displaced workers, or community-based support initiatives in areas with high concentrations of textile employment. Given fiscal constraints, international support would likely be necessary to fund such programmes adequately.

Medium to Long-term Strategies

Beyond immediate crisis response, Sri Lanka must develop strategies to reduce vulnerability to future trade shocks and create a more resilient economic model. Several approaches deserve consideration.

Page 21 of 29

Market Diversification Beyond the United States

Reducing dependence on the U.S. market represents an obvious but challenging strategy. Potential alternative markets include,

* European Union: Already Sri Lanka’s second-largest export destination, the EU offers preferential access through its GSP+ scheme. Expanding exports to Europe would require meeting stringent standards and potentially adjusting product offerings to suit European consumer preferences.

* Regional Markets: Increasing exports to India, China, and other Asian economies could leverage geographical proximity and growing middle-class consumer bases. This would require navigating complex regional trade agreements and potentially developing new product categories better suited to these markets.

* Emerging Markets: Countries in the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America represent potential growth opportunities, though penetrating these markets would require significant market research and relationship building.

The Joint Apparel Association Forum’s statement that “We have no alternate market that we can possibly target instead of the US” reflects the difficulty of this transition. Established buyer relationships, specialized production capabilities, and compliance certifications all create path dependencies that make market diversification a multi-year project rather than an immediate solution.

Product Diversification Beyond Textiles

Sri Lanka’s heavy reliance on textile and apparel exports creates vulnerability to sector-specific shocks. Diversifying the export basket could create greater resilience, though this too represents a long-term structural challenge rather than a quick fix.

Promising sectors for export diversification include:

* Information Technology and Business Process Outsourcing: Sri Lanka has developed a growing IT/BPO sector that could be expanded with appropriate investment in education, infrastructure, and international marketing.

* High-Value Agricultural Products: Speciality tea, spices, and organic produce could command premium prices in international markets while building on Sri Lanka’s agricultural traditions.

Page 22 of 29

Sustainable Manufacturing: Leveraging Sri Lanka’s relatively strong environmental credentials to develop green manufacturing capabilities in emerging sectors like electric vehicle components or renewable energy equipment.

Tourism Services: While not directly affected by goods tariffs, expanding tourism could help diversify foreign exchange earnings. However, this sector’s vulnerability to external shocks (as demonstrated during the pandemic) suggests it should be one component of a diversification strategy rather than its centrepiece.

Successful product diversification would require coordinated public-private investment in research and development, skills training, quality infrastructure, and international marketing. It would also necessitate a supportive policy environment that reduces barriers to innovation and entrepreneurship.

Value Chain Upgrading

Even within existing export sectors like textiles, Sri Lanka could pursue strategies to capture more value and reduce vulnerability to tariffs. Moving up the value chain from basic contract manufacturing to design, product development, branding, and direct-to-consumer sales could increase margins and provide greater control over market access.

Some Sri Lankan companies have already begun this transition, developing their own brands or establishing direct relationships with consumers through e-commerce platforms. Government support for such initiatives through design education, intellectual property protection, and export promotion could accelerate this evolution.

Regional Trade Integration

Deepening integration with regional trade blocs could provide both alternative markets and opportunities for participation in regional value chains. Sri Lanka is a member of the South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA) and has bilateral trade agreements with India, Pakistan, and Singapore, and more recently with Thailand, though implementation challenges have limited their effectiveness.

More ambitious regional integration through mechanisms like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) or the proposed Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) Free

Page 23 of 29

Trade Area could create new opportunities. However, managing domestic concerns about increased competition from larger economies like India and China would require careful policy design and implementation. (To be continued)

(The writer served as the Minister of Justice, Finance and Foreign Affairs of Sri Lanka)

Disclaimer:

This article contains projections and scenario-based analysis based on current economic trends, policy statements, and historical behaviour patterns. While every effort has been made to ensure factual accuracy using publicly available data and established economic models, certain details, particularly regarding future policy decisions and their impacts, remain hypothetical. These projections are intended to inform discussion and analysis, not to predict outcomes with certainty.

(To be concluded)

Opinion

Joy of reading

One of the well-known benefits of reading is that you can get enormous fun from what you read. Many great writers have written funny or entertaining or even stimulating pieces of great literature. But you will have to be introduced to famous works as, although you are students of English, no-one will trouble themselves to explain, show or bring these works to your attention. So read on…

Charles Dickens lived in Victorian London. He has written many amusing pieces in his “Pickwick Papers.” He describes the adventures of Mr Pickwick, and describes Mr Pecksniff and even the snuff and drinking habits of dear old Sairy Gamp who attends to the recently dead and prepares them for sending to the mortuary. These are just two of the many characters found in “Pickwick Papers” (The amazing adventures of the Pickwick Club.) These Pickwick Papers were very popular only a generation or two ago. His colourful descriptions allow our imaginations to conjure up vivid Victorian London scenes. Life in the villages of England was very difficult and everyone thought London was a paradise for work, food and good beer! Everyone eagerly bought Pickwick Papers to learn more of the Pickwick Club and events in London, that dream destination for all English villagers.

No-one will introduce you to Longfellow’s “The Pied Piper of Hamelin.” This poem is based on an old legend. It was said that a plague of rats was running wild in a small town in Germany about 800 years ago. The Pied Piper came and rid the town of rats. He did this for a fee, a good reward, but then was denied payment by the Mayor who had commissioned him to remove the rats. The revenge of the Pied Piper on the town is quite shocking. Longfellow’s powerful descriptions on the several scenes of dramatic action make this poem a charming piece of English literature.

William Wordsworth’s “Daffodils” is a most powerfully evocative poem with words carefully chosen to describe what he saw. The writing is when he viewed thousands of bright yellow daffodils dancing in the breeze (gentle wind) creating a great vista for his viewing, which remained with him and brought pleasure to him in quiet moments. This is the English language waiting for all students to explore.

There are plenty of dismal, turgid writings about historical injustice and brutality by colonisers to countless oppressed people around the world – such writers have a valid message but here we want to introduce a pleasant reading matter that elevates the reader to gain pleasant satisfaction and new good ideas from what he reads. There are many wonderful stories and great writers waiting for the reader to discover many beautiful writings that will make him or her happy.

William Henry Davis, a Welshman and vagrant wanderer, wrote a most charming, beautiful poem: “What is this Life if Full of Care?” He writes about how he regrets that we humans are always in a hurry, too busy to notice or see the delights of nature, and scenes of natural beauty, e.g., a young woman’s smile as she passes by; we have no time to make friends and even kiss her. Regrets!

This is the real English to be tasted and then swigged at lustily in pleasure and satisfaction, not some writing airing historical grievances for children to study!

Priyantha Hettige

Opinion

Trump tariffs and their effect on world trade and economy with particular reference to Sri Lanka – Part II

(Continued from yesterday)

Wharton Budget Model Analysis

The Penn Wharton Budget Model (PWBM), a nonpartisan research initiative that analyses the economic impact of public policies, has conducted a detailed assessment of Trump’s tariff plan. Their findings paint an even more concerning picture of the long-term economic consequences.

According to PWBM’s analysis, Trump’s tariffs (as of April 8, 2025) are projected to reduce long-run GDP by approximately 6% and wages by 5%. For perspective, this represents a more severe economic impact than would result from raising the corporate income tax from 21% to 36%, a change that would be considered highly distortionary by most economists. For a middle-income household, these tariffs translate to an estimated $22,000 lifetime loss in economic welfare.

The PWBM analysis highlights that many existing trade and macroeconomic models fail to capture the full harm caused by tariffs. Beyond their direct effects on prices and trade volumes, larger tariffs reduce the openness of the economy, including international capital flows. This is particularly problematic in the context of the United States’ current debt trajectory, which is increasing faster than GDP. As foreign purchases of U.S. government debt decline due to reduced trade, American households must absorb more of this debt, diverting savings away from productive capital investment.

While the Trump administration has emphasised the revenue-generating potential of these tariffs, projected at $5.2 trillion over ten years on a conventional basis, the PWBM notes that this revenue comes at an extraordinarily high cost in terms of economic efficiency. The tariffs effectively function as a highly distortionary tax that reduces economic activity far more than alternative revenue-raising measures would.

Disruption of Global Supply Chains

Beyond these macroeconomic projections lies the complex reality of global supply chains that have been optimised over decades of increasing trade integration. Modern manufacturing rarely occurs entirely within a single country; instead, components and intermediate goods often cross borders multiple times before a final product is assembled. The sudden imposition of high tariffs disrupts these carefully calibrated production networks, forcing companies to make costly adjustments or pass increased costs on to consumers.

Industries particularly vulnerable to these disruptions include electronics, automobiles, pharmaceuticals, and textiles sectors, where production is highly fragmented across countries. For example, a smartphone might include components from dozens of countries, each potentially subject to different tariff rates under Trump’s country-specific approach. This complexity makes it extremely difficult for businesses to quickly adapt to the new tariff landscape, leading to production inefficiencies, higher costs, and potential shortages of certain goods.

Retaliatory Measures and Trade Policy Uncertainty

The impact of Trump’s tariffs is further magnified by retaliatory measures from affected countries. China has already responded by imposing a minimum 125% tariff on U.S. goods and restricting exports of rare earth elements critical to high-tech industries. The European Union, Canada, Mexico, and other major trading partners have also announced or are considering countermeasures.

These retaliatory tariffs create a negative feedback loop that further reduces global trade and economic activity. They also contribute to what economists call “trade policy uncertainty”, a measurable phenomenon that has been shown to depress investment, hiring, and consumption as businesses and households delay economic decisions in the face of unpredictable policy changes.

By the end of March 2025, the Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) Index had reached its highest point since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, doubling in value from the start of January. Research suggests that this level of uncertainty alone could reduce business investment by approximately 4.4% in 2025, even before accounting for the direct effects of the tariffs themselves.

Disproportionate Impact on Developing Economies

While the economic costs of Trump’s tariffs will be felt globally, they will not be distributed equally. Developing economies, particularly those that have built their development strategies around export-oriented manufacturing, face disproportionate risks.

Unlike wealthy nations with diverse economies and substantial domestic markets, many developing countries rely heavily on exports to generate foreign exchange, create jobs, and drive economic growth. The sudden imposition of high tariffs on their exports to the world’s largest consumer market represents an existential threat to this development model.

Moreover, developing countries typically have fewer resources to cushion the economic shock of reduced exports. Limited fiscal space, higher borrowing costs, and often fragile social safety nets mean that job losses in export sectors can quickly translate into broader economic hardship and potential social instability.

For countries already facing debt sustainability challenges, like Sri Lanka, the reduction in export earnings can directly threaten their ability to service external debt obligations, potentially triggering new sovereign debt crises. This risk is particularly acute given the current global environment of higher interest rates and tightening financial conditions.

The global economic impact of Trump’s tariffs thus represents not merely a temporary disruption to trade flows but potentially a fundamental challenge to the export-led development model that has helped lift hundreds of millions of people out of poverty over recent decades. As we will explore in subsequent sections, Sri Lanka’s experience offers a particularly illuminating case study of these broader dynamics.

SRI LANKA’S ECONOMY AND TRADE PROFILE

Sri Lanka, an island nation of 22 million people in South Asia, presents a compelling case study of how President Trump’s tariff policies can impact vulnerable developing economies. To understand the full implications of the 44% tariff imposed on Sri Lankan goods, it is essential to first examine the country’s economic situation, its trade relationship with the United States, and the particular significance of its textile industry.

Overview of Sri Lanka’s Economic Situation

Sri Lanka has experienced a tumultuous economic journey in recent years. In April 2022, the country became the first in the Asia-Pacific region to default on its external debt since 1999, marking the culmination of a severe economic crisis that had been building for several years. This crisis was precipitated by a perfect storm of factors, the devastating impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on tourism revenues and remittances, rising global commodity prices following supply chain disruptions and the Russia-Ukraine conflict, and questionable economic policies, including significant tax cuts that depleted government revenues.

The economic implosion led to extreme shortages of essential goods, rolling blackouts that sometimes lasted 13 hours, and long queues for fuel and cooking gas. Inflation soared to over 70% at its peak, eroding purchasing power and pushing many Sri Lankans into poverty. The crisis triggered mass protests that ultimately led to the resignation of then-President Gotabaya Rajapaksa in July 2022.

Since then, Sri Lanka has embarked on a painful process of economic stabilization under its 17th program with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The $2.9 billion Extended Fund Facility approved in March 2023 came with stringent conditions, including significant tax increases, reductions in energy subsidies, and other austerity measures designed to reduce the fiscal deficit. The country has also undergone a complex debt restructuring process, reaching agreements with official creditors through the Paris Club and with bondholders who own a significant portion of Sri Lanka’s external debt.

By December 2024, Sri Lanka officially exited sovereign default status after completing its debt restructuring. However, the country’s economic recovery remains fragile. While inflation has moderated and foreign exchange reserves have improved from their crisis lows, GDP growth remains subdued, and the social costs of adjustment have been severe. Poverty rates have increased substantially, and many Sri Lankans continue to struggle with the high cost of living and limited economic opportunities.

Against this backdrop of recent crisis and tentative recovery, the sudden imposition of President Trump’s 44% tariff represents a significant new threat to Sri Lanka’s economic stability and growth prospects.

Sri Lanka-US Trade Relations

The United States has historically been Sri Lanka’s largest export market, accounting for approximately 23% of the country’s total exports. This makes Sri Lanka particularly vulnerable to changes in U.S. trade policy, as nearly a quarter of its foreign exchange earnings through exports depend on continued access to the American market.

The composition of Sri Lanka’s exports to the United States is heavily concentrated in a few key sectors, with textiles and apparel dominating the trade relationship.

Other significant export categories include rubber products, tea, spices, and increasingly, information technology services—though the latter are not directly affected by the tariffs on physical goods.

Sri Lanka has benefited from preferential access to the U.S. market through the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP), which provides duty-free treatment for thousands of products from designated developing countries. However, this program has been subject to periodic reviews based on criteria including labor rights, intellectual property protection, and market access for U.S. goods. Sri Lanka’s GSP benefits were temporarily suspended between 2010 and 2017 due to concerns about labour rights, highlighting the country’s vulnerability to changes in U.S. trade policy even before the current tariff shock.

The trade relationship between the two countries is highly asymmetrical. While the United States is Sri Lanka’s largest export market, Sri Lanka ranks only around 114th among U.S. trading partners. This power imbalance means that Sri Lanka has very limited leverage in bilateral trade negotiations and is largely a price-taker in the relationship.

(To be continued)

(The writer served as the Minister of Justice, Finance and Foreign Affairs of Sri Lanka)

Disclaimer:

This article contains projections and scenario-based analysis based on current economic trends, policy statements, and historical behaviour patterns. While every effort has been made to ensure factual accuracy using publicly available data and established economic models, certain details, particularly regarding future policy decisions and their impacts, remain hypothetical. These projections are intended to inform discussion and analysis, not to predict outcomes with certainty.

by M. U. M. Ali Sabry

President’s Counsel

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoPick My Pet wins Best Pet Boarding and Grooming Facilitator award

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoNew Lankan HC to Australia assumes duties

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoLankan ‘snow-white’ monkeys become a magnet for tourists

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoJapan-funded anti-corruption project launched again

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoKing Donald and the executive presidency

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoACHE Honoured as best institute for American-standard education

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoThe Truth will set us free – I

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoNational Savings Bank appoints Ajith Akmeemana,Chief Financial Officer