Features

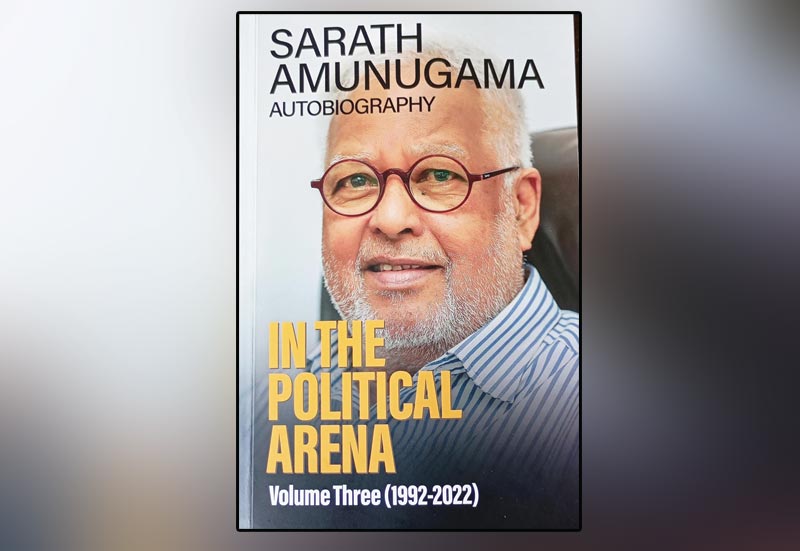

‘In the political arena’

Sarath Amunugama Autobiography

Volume Three (1992 – 2022)

Reviewed by Nigel Hatch, P.C.

Dr. Sarath Amunugama in the final volume of his autobiographical trilogy entitled “In the Political Arena” covers the period 1992 to 2022 which is the contemporary period of politics in Sri Lanka and his frontline role in it.

This memoir covers the presidency of R. Premadasa, the abortive impeachment process against him, the rupture in the UNP and the formation of the DUNF by Lalith Athulatmudali (LA) and Gamini Dissanayake (GD), the author’s sidelining by Ranil Wickremasinghe (RW) in the UNP and his support of Chandika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga (CBK), his Ministerial roles under her presidency and that of Mahinda Rajapaksa and Maithripala Sirisena.

Amunugama in his Introduction observes that as “the modern history of Sri Lanka is full of paradoxes,” asks how did Sri Lanka which at independence had surplus sterling reserves, and one of the most promising States in Asia year marked for modernization and economic growth, end at the bottom of the pile? How is it that a country predominantly Theravada Buddhist could be engaged in fratricidal warfare for almost half the years since independence; and despite a high literacy rate and vibrant intellectual life become reduced to a second rate cultural backwater? One recalls even Lee Kwan Yew trenchantly remarking how we as the envy of Asia had squandered all the positives we had at Independence

The author goes on to explore these tragedies as a failure of a process of modernization and that Sri Lanka 75 years after independence has yet to discover the growth model that suits us. He quotes David Riesman, “The hatred sown by anti-colonialism is harvested in the rejection of every appearance of foreign tutelage. Wanted are modern institutions but not modern ideologies, modern power but not modern purposes, modern wealth but not modern wisdom”.

The failure of economic development is attributed to statist nationalization after 1956 primarily by the SLFP and its “toadies in the left”, the welfare measures commencing from 1933 and rapid population growth which cast an enormous burden on the national exchequer. This led Joan Robinson to sardonically comment “Sri Lanka is trying to taste the fruit of the tree without growing it”.

We are now witnessing the present NPP/JVP Government which has at its core a Marxist orientation, continuing at present with the open economy and the IMF framework for economic stability after the economic meltdown during the Gotabaya Rajapaksa (GR) presidency. The present Government’s continuation of these policies may prove to be more significant than the PA/SLFP’s rejection of the statist model under the leadership of CBK.

Amunugama’s Chapter on R. Premadasa is fittingly entitled “Premadasa Rex (1988 to 1993)”. Although admiring his discipline and his rise to the leadership of the elite dominated UNP, he refers to his “disdainful treatment of Ministers and MPs”. The sidelining of LA and GD, which led to the formation of the DUNF, and the abortive impeachment motion is the subject of a separate chapter.

The abduction and murder of Richard de Zoyza immortalized in the recent film “Rani”, the terror unleashed by the JVP despite Premadasa’s initial sympathy towards them, the testy relationship between Premadasa and Rajiv Gandhi and the withdrawal of the IPKF are discussed.

GD’s return to the UNP under the leadership of President Wijetunga despite obstacles placed within, and the difficulty in finding a place for him on the national list to enter parliament is recounted. Amunugama who had excellent relations with Wijetunga played a seminal role in this endeavor. He states, at first those national list members were unwilling to resign “for love or money”. But persistence prevailed and GD entered parliament and was inducted into the cabinet. GD was assassinated by the LTTE whilst campaigning on the final night for the presidency against CBK. This reviewer accompanied Amunugama and Wickreme Weerasooriya to the President’s House for the meeting with Wijetunga and CBK to discuss funeral arrangements. Amunugama notes that the latter who was PM was extremely gracious, in contrast to her mother’s approach with regard to the funeral arrangements of Dudley Senanayake.

This was a bloody period in Sri Lankan politics, which claimed the lives of Premadasa, Lalith and Gamini and many others , all of whom were assassinated by the LTTE.

Amunugama whose political career commenced as an elected Member of the Provincial Council from the Kandy , and his subsequent election to Parliament in 1994 from the UNP is perhaps the last man standing who could recount with personal knowledge and as an insider and participant to the momentous events of that period which were unparallelled in Sri Lanka’s political history.

The author’s political career as a Minister commenced with the decision that he, Wijayapala Mendis, Susil Moonasinghe, Nanda Mathew and a few others took to support CBK over Ranil Wickremasinghe at the Presidential Election of 2000. Their purported expulsion from the UNP under Ranil Wickremasinghe led to the constitutionally significant decision of the Supreme Court which held that expulsion unlawful is of personal significance to the reviewer whose role as Junior Counsel to the late Elanga Wikramanayake is recounted in this memoir in some detail.

The author’s first portfolio was as Minister of Northern Rehabilitation under the CBK presidency. He records how the Government funded and maintained the infrastructure of the Northern Province, despite the LTTE controlling large swaths of territory. This is perhaps unparalleled, in that, despite the separatist war waged by the LTTE, the GOSL continued to ensure that food, medicines, fuel and other essential supplies reached the citizens of those areas under LTTE control.

The reviewer recalls Amunugama telling him that when he visited New Delhi as an emissary of the former President J.R. Jayewardene, he was told that India would remain indifferent if the Government decided to accelerate its military campaign and bomb strongholds of the LTTE even in built up areas of the northern province. This strategy was never pursued, and the fratricidal warfare continued until the military defeat of the LTTE in 2009 under the leadership of Mahinda Rajapaksa.

Amunugama recounts his subsequent portfolios. His tenure as Minister of Irrigation reflects his love for the land and the people, which undoubtedly commenced when he was a civil servant and served in several parts of the country which is brought out also in Volume 1. His sense of humour is replete even in this volume. Anuruddha Ratwatte, who held this portfolio earlier, was unhappy that CBK did not appoint him to this Ministry. He told the author that he had “looked forward while returning from the war zone to landing his helicopter near the NCP tanks and enjoying a country rice meal wrapped in a lotus leaf. He lost both the war and his lotus leaf wrapped lunch.” (pg. 251).

Sri Lanka experienced the politics of cohabitation between CBK as President, and RW as Prime Minister with a cabinet of his choice, when the latter’s coalition secured the largest number of seats in Parliament at the 2001 elections. She faced a torrid time at some cabinet meetings particularly from those who were at one time trusted lieutenants and had defected from her party and joined the UNP.

Politically these were trying times and CBK who made the mistake of conceding the defense portfolio to a UNP Minister, had to seek the first ever opinion from the Supreme Court under Article 129 as regards these powers. The reviewer appeared for her with the late HL de Silva PC and Raja Goonesekere (RKW) and succeeded in that case. The court held that defense was an integral part of the powers of the President.

Events swiftly ensued and CBK exercised her powers and removed some UNP Ministers and dissolved parliament. The reviewer was involved in strategizing these events and recalls a weekend at the President’s house in Nuwara Eliya where Lakshman Kadiragmar (LK) and Mangala Samaraweera were also present.

Amunugama was one of CBK’s representatives in talks between the SLFP and the JVP represented by Tilwin Silva, Anura Kumara Dissanayake (AKD), Bimal Rathnayake and Sunil Handunetti. He states, “very often I was the only one from our side while all JVPers diligently attended discussions”, exemplified by AKD once attending a meeting after coming from Ampara after skipping his meals to be on time (282).

At the ensuing general elections in 2004, CBK’s party in coalition with the JVP secured power and formed a government. Amunugama became the Minister of Finance, a portfolio which had been the domain of several former presidents. He recounts his experience in this portfolio with extensive references to the challenges faced and negotiations with international lending agencies. He comments positively on the four Ministers from the JVP.

He states that the alliance with the JVP ended when CBK, persuaded by the World Bank and the IMF, negotiated a power sharing arrangement with the LTTE for the rehabilitation of the North and East after the devastating Tsunami of 2004 called the P-TOMS. This initiative was challenged in Court, and this reviewer and RKW led for CBK’s government in separate related cases, whilst HL de Silva, a friend and confidante of CBK, led for the JVP. CBK’s genuine desire for a peaceful negotiated settlement of the ethnic conflict is indisputable. Nevertheless, she had no hesitation on several occasions of directing the navy to blow up LTTE cargo vessels that attempted surreptitiously to smuggle arms during that cease fire.

Amunugama refers to the significant contribution made by Lakshman Kadirgamar PC who was an outstanding foreign minister, and at one point a serious contender to be PM backed by the JVP. The reviewer worked closely with LK on several legal issues including the Ceasefire Agreement that RW as PM unilaterally agreed with the LTTE, difficulties arising from the Norwegian facilitation and required constitutional amendments. LK too was assassinated by the LTTE.

Amunugama unflinchingly refers to the politics of the judiciary when the mercurial Sarath N Silva (SNS), was Chief Justice. He refers to the “Helping Hambantota” controversy, which was a fund set up by MR to collect money in the aftermath of the Tsunami, for the rehabilitation of, “presumably, as its name indicates, the Hambantota district”. He states, “The UNP which worked hand in glove with Mahinda to embarrass CBK, now discovered that their favorite SLPer (MR) whom they nurtured could become a formidable candidate” at the forthcoming presidential election “(p-319).

Kabir Hashim, a UNP MP, challenged the legality of this Fund. Sarath Silva, the then Chief Justice who clipped a year off the term of office that CBK enjoyed in her second term, a decision which he states “was tailor made for his friend Mahinda Rajapaksa”, dismissed that case. Silva subsequently expressed remorse for this decision after he left office, noting that if MR was found guilty, he could have faced imprisonment. Amunugama to his credit admitted in Parliament that the Fund was not properly constituted.

The political ascendancy of Mahinda Rajapaksa, first as the SLFP candidate, and then victorious in the 2005 presidential election by the narrowest of margins over RW, also makes fascinating reading. This was the closest that RW had ever come when he contested the presidency reminiscent of R. Premadasa’s narrow win over Sirimavo Bandaranaike in 1988. This writer recalls Amunugama’s prescient prognostication that with MR’s nomination “CBK had signed her political death warrant”. Relations between the two (CBK and MR) had deteriorated over a period of time, and when The UNP had commenced a long march from the South demanding a presidential election which presaged SN Silva’s judgment on her term of office, she appointed RKW and this reviewer to meet with MR at President’s House. At this meeting MR rightly pressed that a delay in nominating the party candidate would be prejudicial and we duly communicated that to her.

Amunugama was appointed Minister of Public Administration by MR, a portfolio he was happy to get due to his antecedents as a public servant and working with Felix Dias Bandaranaike earlier in that ministry, recounted in Volume 1.

He recounts succinctly the inner politics of the MR administration during that period, including the disaffection of Mangala Samaraweera, his indefatigable campaign manager, due to not being appointed PM, and CBK’s efforts to cause problems for MR. MR faced a potential revolt orchestrated by Anura B and Mangala ostensibly with JVP support, but at the last moment unbeknownst to Anura the JVP pulled out of the arrangement, leaving Anura who crossed over in Parliament, with egg on his face. MR removed Mangala and Anura from their posts and Amunugama notes that Anura never returned to parliament and it was “an ignominious end to a career tailor made to take him to the top.” (348)

His knowledge and experience in economics and finance served him well in his next portfolio, Investment Promotion. As with his other portfolios, Amunugama takes the reader through important events and initiatives that he introduced, including meetings with foreign dignitaries.

The high point of MR’s second term (2009-2015) was the military defeat of the LTTE. He rightly identifies MR as a national hero. The ensuing rift with General Sarath Fonseka, part of the troika with MR and his brother Gotabaya that strategized that victory, could have arisen due to Fonseka’s own plans for the military to bolster his image. Fonseka was wooed by the opposition as a presidential opponent to MR but went on to lose that election in 2010. Instead, he was elected to parliament, and was unsuccessful at the recently concluded presidential election, where he cut a forlorn figure at rallies which were poorly attended.

Amunugama notes that after the war there was a commendable level of economic growth under MR, attributable as in most countries that come out of a long war to budgetary realignments to development projects and donor funding agencies being more receptive and forthcoming. “Accordingly, several highway projects, work on ports and airports, transport and power were undertaken adding to a rapid growth of GDP.” (p-387). Amunugama was given the additional responsibility as Deputy Minister of Finance, and after the parliamentary elections of 2010, was appointed Senior Minister and resumed his role as chief interlocutor with the global financial institutions.

But the decline in MR’s popularity due to the “shenanigans of his relatives” manifested itself in the results of the presidential election of 2015, where he ill-advisedly ran for a third term and lost to Maithripala Sirisena who was nominated by the joint opposition. As a precursor to this maneuver, MR sought an opinion in 2014 from the Supreme Court as to whether he was eligible to run for a third term. A full Bench of the Supreme Court presided over by Mohan Pieris, CJ determined that he was so entitled. Amunugama ruefully states that as regards the removal of the two term limit for a president by the earlier 18th amendment by MR that “however we have to admit that our reluctant vote for this aberration is an unforgivable black mark in our parliamentary record.” (p-416)

Amunugama deals with “The One Term President Maithripala Sirisena (2015-2020)” in the penultimate chapter. The deterioration in the relations between Sirisena, described as an “unreconstructed Marxist with strong socialist views” and RW due to the bond scam, and RW’s sacking as PM, MR’s reinduction as PM for a short period and the ill-advised dissolution of Parliament which was struck down by the Supreme Court are recounted.

This memoir concludes with an Epilogue which covers the political ascendancy of Gotabaya Rajapaksa (GR) , the split in the UNP and formation of the SJB under Sajith Premadasa, and a succinct analysis of the economic debacle under the GR presidency and the resulting Aragalaya . GR was forced into exile due to that popular and peaceful uprising and the “bargain basement sale” of the office of PM, which RW ultimately secured. This catapulted him as the unelected president for the remainder of GR’s term by a vote in Parliament with the backing of MR and his party. The Supreme Court has now held by a majority that the Emergency Regulations he used to end the Aragalaya were violative of Fundamental Rights.

This three-volume memoir is an indispensable reference for the post-independence socio-economic and political history of Sri Lanka and is a rich tapestry of the life and times of a brilliant and now preeminent elder statesman whose sagacity and involvement in national affairs is sorely missed.

Amunugama has spent his adult life in the service of the nation. He has brought into public life, at the highest levels, Minister of inter alia Finance, Irrigation, Education and briefly Foreign Affairs, integrity, intellectual rigor and pragmatism. As with the earlier two volumes, Amunugama writes with clarity and effortless style. His love for culture and the arts- books, and theatre are manifest in this volume as well, which are spliced with lovely images from his personal collection of George Keyt’s art.

Features

Pakistan-Sri Lanka ‘eye diplomacy’

Reminiscences:

I was appointed Managing Director of the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC) and Chairman of the Trincomalee Petroleum Terminals Ltd (TPTL – Indian Oil Company/ Petroleum Corporation of Sri Lanka joint venture), in February 2023, by President Ranil Wickremesinghe. I served as TPTL Chairman voluntarily. TPTL controls the world-renowned oil tank farm in Trincomalee, abandoned after World War II. Several programmes were launched to repair tanks and buildings there. I enjoyed travelling to Trincomalee, staying at Navy House and monitoring the progress of the projects. Trincomalee is a beautiful place where I spent most of my time during my naval career.

My main task as MD, CPC, was to ensure an uninterrupted supply of petroleum products to the public.

With the great initiative of the then CPC Chairman, young and energetic Uvis Mohammed, and equally capable CPC staff, we were able to do our job diligently, and all problems related to petroleum products were overcome. My team and I were able to ensure that enough stocks were always available for any contingency.

The CPC made huge profits when we imported crude oil and processed it at our only refinery in Sapugaskanda, which could produce more than 50,000 barrels of refined fuel in one stream working day! (One barrel is equal to 210 litres). This huge facility encompassing about 65 acres has more than 1,200 employees and 65 storage tanks.

A huge loss the CPC was incurring due to wrong calculation of “out turn loss” when importing crude oil by ships and pumping it through Single Point Mooring Buoy (SPMB) at sea and transferring it through underwater fuel transfer lines to service tanks was detected and corrected immediately. That helped increase the CPC’s profits.

By August 2023, the CPC made a net profit of 74,000 million rupees (74 billion rupees)! The President was happy, the government was happy, the CPC Management was happy and the hard-working CPC staff were happy. I became a Managing Director of a very happy and successful State-Owned Enterprise (SOE). That was my first experience in working outside military/Foreign service.

I will be failing in my duty if I do not mention Sagala Rathnayake, then Chief of Staff to the President, for recommending me for the post of MD, CPC.

The only grievance they had was that we were not able to pay their 2023 Sinhala/Tamil New Year bonus due to a government circular. After working at CPC for six months and steering it out of trouble, I was ready to move out of CPC.

I was offered a new job as the Sri Lanka High Commissioner to Pakistan. I was delighted and my wife and son were happy. Our association with Pakistan, especially with the Pakistan Military, is very long. My son started schooling in Karachi in 1995, when I was doing the Naval War Course there. My wife Yamuna has many good friends in Pakistan. I am the first Military officer to graduate from the Karachi University in 1996 (BSc Honours in War Studies) and have a long association with the Pakistan Navy and their Special Forces. I was awarded the Nishan-e-Imtiaz (Military) medal—the highest National award by the Pakistan Presidentm in 2019m when I was Chief of Defence Staff. I am the only Sri Lankan to have been awarded this prestigious medal so far. I knew my son and myself would be able to play a quiet game of golf every morning at the picturesque Margalla Golf Club, owned by the Pakistan Navy, at the foot of Margalla hills, at Islamabad. The golf club is just a walking distance from the High Commissioner’s residence.

When I took over as Sri Lanka High Commissioner at Islamabad on 06 December 2023, I realised that a number of former Service Commanders had held that position earlier. The first Ceylonese High Commissioner to Pakistan, with a military background, was the first Army Commander General Anton Muthukumaru. He was concurrently Ambassador to Iran. Then distinguished Service Commanders, like General H W G Wijayakoon, General Gerry Silva, General Srilal Weerasooriya, Air Chief Marshal Jayalath Weerakkody, served as High Commissioners to Islamabad. I took over from Vice Admiral Mohan Wijewickrama (former Chief of Staff of Navy and Governor Eastern Province).

A photograph of Dr. Silva (second from right) in Brigadier

(Dr) Waquar Muzaffar’s album

One of the first visitors I received was Kawaja Hamza, a prominent Defence Correspondent in Islamabad. His request had nothing to do with Defence matters. He wanted to bring his 84-year-old father to see me; his father had his eyesight restored with corneas donated by a Sri Lankan in 1972! His eyesight is still good, but he did not know the Sri Lankan donor who gave him this most precious gift. He wanted to pay gratitude to the new Sri Lankan High Commissioner and to tell him that as a devoted Muslim, he prayed for the unknown donor every day! That reminded me of what my guru in Foreign Service, the late Foreign Minister Lakshman Kadirgamar told me when I was First Secretary/ Defence Advisor, Sri Lanka High Commission in New Delhi. That is “best diplomacy is people-to-people contacts.” This incident prompted me to research more into “Pakistan-Sri Lanka Eye Diplomacy” and what I learnt was fascinating!

Do you know the Sri Lanka Eye Donation Society has donated more than 26,000 corneas to Pakistan, since 1964 to date! That means more than 26,000 Pakistani people see the world with SRI LANKAN EYES! The Sri Lankan Eye Donation Society has provided 100,000 eye corneas to foreign countries FREE! To be exact 101,483 eye corneas during the last 65 years! More than one fourth of these donations was to one single country- Pakistan. Recent donations (in November 2024) were made to the Pakistan Military at Armed Forces Institute of Ophthalmology (AFIO), Rawalpindi, to restore the sight of Pakistan Army personnel who suffered eye injuries due to Improvised Explosive Devices (IED) blasts. This donation was done on the 75th Anniversary of the Sri Lanka Army.

Deshabandu Dr. F. G. Hudson Silva, a distinguished old boy of Nalanda College, Colombo, started collecting eye corneas as a medical student in 1958. His first set of corneas were collected from a deceased person and were stored at his home refrigerator at Wijerama Mawatha, Colombo 7. With his wife Iranganie De Silva (nee Kularatne), he started the Sri Lanka Eye Donation Society in 1961. They persuaded Buddhists to donate their eyes upon death. This drive was hugely successful.

Their son (now in the US) was a contemporary of mine at Royal College. I pledged to donate (of course with my parents’ permission) my eyes upon my death when I was a student at Royal college in 1972 on a Poson Full Moon Poya Day. Thousands have done so.

On Vesak Full Moon Poya Day in 1964, the first eye corneas were carried in a thermos flask filled with Ice, to Singapore, by Dr Hudson Silva and his wife and a successful eye transplant surgery was performed. From that day, our eye corneas were sent to 62 different countries.

Pakistan Lions Clubs, which supported this noble gesture, built a beautiful Eye Hospital for humble people at Gulberg, Lahore, where eye surgeries are performed, and named it Dr Hudson Silva Lions Eye Hospital.

The good work has continued even after the demise of Dr Hudson Silva in 1999.

So many people have donated their eyes upon their death, including President J. R. Jayewardene, whose eye corneas were used to restore the eyesight of one Japanese and one Sri Lankan. Dr Hudson Silva became a great hero in Pakistan and he was treated with dignity and respect whenever he visited Pakistan. My friend, Brigadier (Dr) Waquar Muzaffar, the Commandant of AFIO, was able to dig into his old photographs and send me a precious photo taken in 1980, 46 years ago (when he was a medical student), with Dr Hudson Silva.

We will remember Dr and Mrs Hudson Silva with gratitude.

Bravo Zulu to Sri Lanka Eye Donation Society!

by Admiral Ravindra C Wijegunaratne

by Admiral Ravindra C Wijegunaratne

WV, RWP and Bar, RSP, VSV, USP, NI (M) (Pakistan), ndc, psn, Bsc

(Hons) (War Studies) (Karachi) MPhil (Madras)

Former Navy Commander and Former Chief of Defense Staff

Former Chairman, Trincomalee Petroleum Terminals Ltd

Former Managing Director Ceylon Petroleum Corporation

Former High Commissioner to Pakistan

Features

Lasting solutions require consensus

Problems and solutions in plural societies like Sri Lanka’s which have deep rooted ethnic, religious and linguistic cleavages require a consciously inclusive approach. A major challenge for any government in Sri Lanka is to correctly identify the problems faced by different groups with strong identities and find solutions to them. The durability of democratic systems in divided societies depends less on electoral victories than on institutionalised inclusion, consultation, and negotiated compromise. When problems are defined only through the lens of a single political formation, even one that enjoys a large electoral mandate, such as obtained by the NPP government, the policy prescriptions derived from that diagnosis will likely overlook the experiences of communities that may remain outside the ruling party. The result could end up being resistance to those policies, uneven implementation and eventual political backlash.

A recent survey done by the National Peace Council (NPC), in Jaffna, in the North, at a focus group discussion for young people on citizen perception in the electoral process, revealed interesting developments. The results of the NPC micro survey support the findings of the national survey by Verite Research that found that government approval rating stood at 65 percent in early February 2026. A majority of the respondents in Jaffna affirm that they feel safer and more fairly treated than in the past. There is a clear improving trend to be seen in some areas, but not in all. This survey of predominantly young and educated respondents shows 78 percent saying livelihood has improved and an equal percentage feeling safe in daily life. 75 percent express satisfaction with the new government and 64 percent believe the state treats their language and culture fairly. These are not insignificant gains in a region that bore the brunt of three decades of war.

Yet the same survey reveals deep reservations that temper this optimism. Only 25 percent are satisfied with the handling of past issues. An equal percentage see no change in land and military related concerns. Most strikingly, almost 90 percent are worried about land being taken without consent for religious purposes. A significant number are uncertain whether the future will be better. These negative sentiments cannot be brushed aside as marginal. They point to unresolved structural questions relating to land rights, demilitarisation, accountability and the locus of political power. If these issues are not addressed sooner rather than later, the current stability may prove fragile. This suggests the need to build consensus with other parties to ensure long-term stability and legitimacy, and the need for partnership to address national issues.

NPP Absence

National or local level problems solving is unlikely to be successful in the longer term if it only proceeds from the thinking of one group of people even if they are the most enlightened. Problem solving requires the engagement of those from different ethno-religious, caste and political backgrounds to get a diversity of ideas and possible solutions. It does not mean getting corrupted or having to give up the good for the worse. It means testing ideas in the public sphere. Legitimacy flows not merely from winning elections but from the quality of public reasoning that precedes decision-making. The experience of successful post-conflict societies shows that long term peace and development are built through dialogue platforms where civil society organisations, political actors, business communities, and local representatives jointly define problems before negotiating policy responses.

As a civil society organisation, the National Peace Council engages in a variety of public activities that focus on awareness and relationship building across communities. Participants in those activities include community leaders, religious clergy, local level government officials and grassroots political party representatives. However, along with other civil society organisations, NPC has been finding it difficult to get the participation of members of the NPP at those events. The excuse given for the absence of ruling party members is that they are too busy as they are involved in a plenitude of activities. The question is whether the ruling party members have too much on their plate or whether it is due to a reluctance to work with others.

The general belief is that those from the ruling party need to get special permission from the party hierarchy for activities organised by groups not under their control. The reluctance of the ruling party to permit its members to join the activities of other organisations may be the concern that they will get ideas that are different from those held by the party leadership. The concern may be that these different ideas will either corrupt the ruling party members or cause dissent within the ranks of the ruling party. But lasting reform in a plural society requires precisely this exposure. If 90 percent of surveyed youth in Jaffna are worried about land issues, then engaging them, rather than shielding party representatives from uncomfortable conversations, is essential for accurate problem identification.

North Star

The Leader of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), Prof Tissa Vitarana, who passed away last week, gave the example for national level problem solving. As a government minister he took on the challenge the protracted ethnic conflict that led to three decades of war. He set his mind on the solution and engaged with all but never veered from his conviction about what the solution would be. This was the North Star to him, said his son to me at his funeral, the direction to which the Compass (Malimawa) pointed at all times. Prof Vitarana held the view that in a diverse and plural society there was a need to devolve power and share power in a structured way between the majority community and minority communities. His example illustrates that engagement does not require ideological capitulation. It requires clarity of purpose combined with openness to dialogue.

The ethnic and religious peace that prevails today owes much to the efforts of people like Prof Vitarana and other like-minded persons and groups which, for many years, engaged as underdogs with those who were more powerful. The commitment to equality of citizenship, non-racism, non-extremism and non-discrimination, upheld by the present government, comes from this foundation. But the NPC survey suggests that symbolic recognition and improved daily safety are not enough. Respondents prioritise personal safety, truth regarding missing persons, return of land, language use and reduction of military involvement. They are also asking for jobs after graduation, local economic opportunity, protection of property rights, and tangible improvements that allow them to remain in Jaffna rather than migrate.

If solutions are to be lasting they cannot be unilaterally imposed by one party on the others. Lasting solutions cannot be unilateral solutions. They must emerge from a shared diagnosis of the country’s deepest problems and from a willingness to address the negative sentiments that persist beneath the surface of cautious optimism. Only then can progress be secured against reversal and anchored in the consent of the wider polity. Engaging with the opposition can help mitigate the hyper-confrontational and divisive political culture of the past. This means that the ruling party needs to consider not only how to protect its existing members by cloistering them from those who think differently but also expand its vision and membership by convincing others to join them in problem solving at multiple levels. This requires engagement and not avoidance or withdrawal.

by Jehan Perera

Features

Unpacking public responses to educational reforms

As the debate on educational reforms rages, I find it useful to pay as much attention to the reactions they have excited as we do to the content of the reforms. Such reactions are a reflection of how education is understood in our society, and this understanding – along with the priorities it gives rise to – must necessarily be taken into account in education policy, including and especially reform. My aim in this piece, however, is to couple this public engagement with critical reflection on the historical-structural realities that structure our possibilities in the global market, and briefly discuss the role of academics in this endeavour.

As the debate on educational reforms rages, I find it useful to pay as much attention to the reactions they have excited as we do to the content of the reforms. Such reactions are a reflection of how education is understood in our society, and this understanding – along with the priorities it gives rise to – must necessarily be taken into account in education policy, including and especially reform. My aim in this piece, however, is to couple this public engagement with critical reflection on the historical-structural realities that structure our possibilities in the global market, and briefly discuss the role of academics in this endeavour.

Two broad reactions

The reactions to the proposed reforms can be broadly categorised into ‘pro’ and ‘anti’. I will discuss the latter first. Most of the backlash against the reforms seems to be directed at the issue of a gay dating site, accidentally being linked to the Grade 6 English module. While the importance of rigour cannot be overstated in such a process, the sheer volume of the energies concentrated on this is also indicative of how hopelessly homophobic our society is, especially its educators, including those in trade unions. These dispositions are a crucial part of the reason why educational reforms are needed in the first place. If only there was a fraction of the interest in ‘keeping up with the rest of the world’ in terms of IT, skills, and so on, in this area as well!

Then there is the opposition mounted by teachers’ trade unions and others about the process of the reforms not being very democratic, which I (and many others in higher education, as evidenced by a recent statement, available at https://island.lk/general-educational-reforms-to-what-purpose-a-statement-by-state-university-teachers/ ) fully agree with. But I earnestly hope the conversation is not usurped by those wanting to promote heteronormativity, further entrenching bigotry only education itself can save us from. With this important qualification, I, too, believe the government should open up the reform process to the public, rather than just ‘informing’ them of it.

It is unclear both as to why the process had to be behind closed doors, as well as why the government seems to be in a hurry to push the reforms through. Considering other recent developments, like the continued extension of emergency rule, tabling of the Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), and proposing a new Authority for the protection of the Central Highlands (as is famously known, Authorities directly come under the Executive, and, therefore, further strengthen the Presidency; a reasonable question would be as to why the existing apparatus cannot be strengthened for this purpose), this appears especially suspect.

Further, according to the Secretary to the MOE Nalaka Kaluwewa: “The full framework for the [education] reforms was already in place [when the Dissanayake government took office]” (https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2025/08/12/wxua-a12.html, citing The Morning, July 29). Given the ideological inclinations of the former Wickremesinghe government and the IMF negotiations taking place at the time, the continuation of education reforms, initiated in such a context with very little modification, leaves little doubt as to their intent: to facilitate the churning out of cheap labour for the global market (with very little cushioning from external shocks and reproducing global inequalities), while raising enough revenue in the process to service debt.

This process privileges STEM subjects, which are “considered to contribute to higher levels of ‘employability’ among their graduates … With their emphasis on transferable skills and demonstrable competency levels, STEM subjects provide tools that are well suited for the abstraction of labour required by capitalism, particularly at the global level where comparability across a wide array of labour markets matters more than ever before” (my own previous piece in this column on 29 October 2024). Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS) subjects are deprioritised as a result. However, the wisdom of an education policy that is solely focused on responding to the global market has been questioned in this column and elsewhere, both because the global market has no reason to prioritise our needs as well as because such an orientation comes at the cost of a strategy for improving the conditions within Sri Lanka, in all sectors. This is why we need a more emancipatory vision for education geared towards building a fairer society domestically where the fruits of prosperity are enjoyed by all.

The second broad reaction to the reforms is to earnestly embrace them. The reasons behind this need to be taken seriously, although it echoes the mantra of the global market. According to one parent participating in a protest against the halting of the reform process: “The world is moving forward with new inventions and technology, but here in Sri Lanka, our children are still burdened with outdated methods. Opposition politicians send their children to international schools or abroad, while ours depend on free education. Stopping these reforms is the lowest act I’ve seen as a mother” (https://www.newsfirst.lk/2026/01/17/pro-educational-reforms-protests-spread-across-sri-lanka). While it is worth mentioning that it is not only the opposition, nor in fact only politicians, who send their children to international schools and abroad, the point holds. Updating the curriculum to reflect the changing needs of a society will invariably strengthen the case for free education. However, as mentioned before, if not combined with a vision for harnessing education’s emancipatory potential for the country, such a move would simply translate into one of integrating Sri Lanka to the world market to produce cheap labour for the colonial and neocolonial masters.

According to another parent in a similar protest: “Our children were excited about lighter schoolbags and a better future. Now they are left in despair” (https://www.newsfirst.lk/2026/01/17/pro-educational-reforms-protests-spread-across-sri-lanka). Again, a valid concern, but one that seems to be completely buying into the rhetoric of the government. As many pieces in this column have already shown, even though the structure of assessments will shift from exam-heavy to more interim forms of assessment (which is very welcome), the number of modules/subjects will actually increase, pushing a greater, not lesser, workload on students.

A file photo of a satyagraha against education reforms

What kind of education?

The ‘pro’ reactions outlined above stem from valid concerns, and, therefore, need to be taken seriously. Relatedly, we have to keep in mind that opening the process up to public engagement will not necessarily result in some of the outcomes, those particularly in the HSS academic community, would like to see, such as increasing the HSS component in the syllabus, changing weightages assigned to such subjects, reintroducing them to the basket of mandatory subjects, etc., because of the increasing traction of STEM subjects as a surer way to lock in a good future income.

Academics do have a role to play here, though: 1) actively engage with various groups of people to understand their rationales behind supporting or opposing the reforms; 2) reflect on how such preferences are constituted, and what they in turn contribute towards constituting (including the global and local patterns of accumulation and structures of oppression they perpetuate); 3) bring these reflections back into further conversations, enabling a mutually conditioning exchange; 4) collectively work out a plan for reforming education based on the above, preferably in an arrangement that directly informs policy. A reform process informed by such a dialectical exchange, and a system of education based on the results of these reflections, will have greater substantive value while also responding to the changing times.

Two important prerequisites for this kind of endeavour to succeed are that first, academics participate, irrespective of whether they publicly endorsed this government or not, and second, that the government responds with humility and accountability, without denial and shifting the blame on to individuals. While we cannot help the second, we can start with the first.

Conclusion

For a government that came into power riding the wave of ‘system change’, it is perhaps more important than for any other government that these reforms are done for the right reasons, not to mention following the right methods (of consultation and deliberation). For instance, developing soft skills or incorporating vocational education to the curriculum could be done either in a way that reproduces Sri Lanka’s marginality in the global economic order (which is ‘system preservation’), or lays the groundwork to develop a workforce first and foremost for the country, limited as this approach may be. An inextricable concern is what is denoted by ‘the country’ here: a few affluent groups, a majority ethno-religious category, or everyone living here? How we define ‘the country’ will centrally influence how education policy (among others) will be formulated, just as much as the quality of education influences how we – students, teachers, parents, policymakers, bureaucrats, ‘experts’ – think about such categories. That is precisely why more thought should go to education policymaking than perhaps any other sector.

(Hasini Lecamwasam is attached to the Department of Political Science, University of Peradeniya).

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

-

Life style3 days ago

Life style3 days agoMarriot new GM Suranga

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoMonks’ march, in America and Sri Lanka

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoWill computers ever be intelligent?

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoThe Rise of Takaichi

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoWetlands of Sri Lanka:

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoThailand to recruit 10,000 Lankans under new labour pact

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoMassive Sangha confab to address alleged injustices against monks