Life style

Gehan makes Sri Lanka proud with ‘The Billionaire’

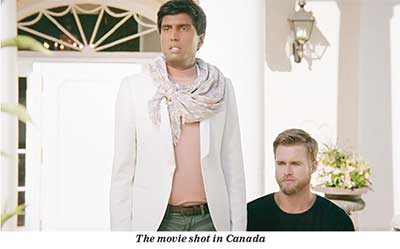

The gifted and versatile actor Gehan Cooray makes Sri Lanka proud with his Hollywood movie “Billionaire” . This movie was awarded at the prestigious Burbank International film recently.

This film was Gehan Cooray’s very own adaptation of George Bernard Show’s play ‘The Millionairess’ Gehan’s milestone in producing, writing the screen play and his portrayal in the title role were great achievements.

Based in Los Angeles, Gehan Cooray is also an actor, independent filmmaker and a classical singer. The film ‘The Billionaire’ was officially submitted to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and to the Hollywood Foreign Press Association in late 2020, after becoming eligible for both Oscar and Golden Globe awards nominations.

by Zanita Careem

How did you get involved in the movie The Billionaire”

At the tender age of three , my mother introduced me to Classic Hollywood films like ‘My Fair Lady’, ‘The Sound of Music’ and ‘Mary Poppins’, which left an indelible impression on my mind. Throughout my childhood, I was struck by how movies could offer the viewer a form of audio-visual escapism that was practically unrivalled. However, since there was no English film industry in Sri Lanka, I grew up performing on the stage, and didn’t seriously consider becoming a filmmaker until I attended the University of Southern California, in Los Angeles.

USC of course has the best cinematic arts school in the world, producing such Hollywood luminaries as George Lucas. Although I majored in Theatre and Psychology, I took as many cinema classes as I possibly could, and discovered a knack for filmmaking through class projects and such. It was several years after graduating from university, however, that a chance meeting with the famous director Jon Favreau in Hollywood set me on my current trajectory. Seeing my USC sweatshirt, he asked me if I was a filmmaker. My instinct at the time was to say “I’m an Actor and a Singer, but not really a filmmaker” – and yet, I subsequently said to myself….”If Mr. Favreau thinks I look like I could be making films, on top of being a performer, why not give it a go, since I’ve had such an excellent foundation at USC anyway?”

USC of course has the best cinematic arts school in the world, producing such Hollywood luminaries as George Lucas. Although I majored in Theatre and Psychology, I took as many cinema classes as I possibly could, and discovered a knack for filmmaking through class projects and such. It was several years after graduating from university, however, that a chance meeting with the famous director Jon Favreau in Hollywood set me on my current trajectory. Seeing my USC sweatshirt, he asked me if I was a filmmaker. My instinct at the time was to say “I’m an Actor and a Singer, but not really a filmmaker” – and yet, I subsequently said to myself….”If Mr. Favreau thinks I look like I could be making films, on top of being a performer, why not give it a go, since I’ve had such an excellent foundation at USC anyway?”

I started with a few short films, which got into some big film festivals in Los Angeles and Palm Springs. Having received that kind of recognition for my work, my mother felt it was time for me to take the plunge and make a feature length film – which is what led to “THE BILLION AIRE”. I wanted to make a film that hearkened back to the elegance and sophistication of the Old Hollywood films I grew up watching.

How long did you take to make research and make the film?

It took several years. It was definitely a marathon, not a sprint, and it sometimes felt like I would never reach the finish line, honestly, but by the Grace of God, I finally did, overcoming all kinds of obstacles that seemed insurmountable to the point of despair at the time – but my Patience and Perseverance won out.

What were the key challenges in making ‘The Billionaire’

I had a number of people try to take advantage of me and bleed me dry in the most unscrupulous of ways, and so I would say the key challenge was finding the right collaborators whom I could really trust, and who had the film’s best interests in mind, versus their own best interests. This is always a challenge when you are producing a film as an independent filmmaker.

On a more artistic note, editing the film also proved to be a challenge. The first cut of the film was 2 hours 40 minutes. It took me a long time to find an editor who could help me bring the film under two hours, without sacrificing the main essence and thrust of the story. It was someone at Warner Bros. Studios who referred me to such an editor, who understood what I was trying to accomplish with the film, and respected my vision, without merely slicing and dicing the footage.

Working and producing the movie in Hollywood, tell us your first time experience

The difference between making a short film and making a feature film is like the difference between crawling and running a marathon, and so the short films I had so successfully made prior to THE BILLIONAIRE did not prepare me for what was to come. What helped me from beginning to end, however, was the strength of my artistic convictions – I was not just trying to make a movie, as so many do, but create a work of art that had literary, dramatic and musical merit. The whole process might have been somewhat intimidating, had I not had believed so completely in what I was doing.

Is digital technology and opportunity or a threat?

Digital technology is certainly an opportunity for so many young creative people, but it can also be a threat because anyone can make anything and upload it online – regardless of their level of education or their artistic abilities. Hence, there is such an overabundance of content available online digitally, that finding a work of quality these days can be akin to finding a needle in a haystack. I am still adamant about releasing my film in cinemas first, before taking the digital route, because there is a level of quality control and discernment in cinemas that sadly can’t be found in the digital sphere.

Digital technology is certainly an opportunity for so many young creative people, but it can also be a threat because anyone can make anything and upload it online – regardless of their level of education or their artistic abilities. Hence, there is such an overabundance of content available online digitally, that finding a work of quality these days can be akin to finding a needle in a haystack. I am still adamant about releasing my film in cinemas first, before taking the digital route, because there is a level of quality control and discernment in cinemas that sadly can’t be found in the digital sphere.

What inspired you to produce and star in ‘The Billionaire’?

I wanted to produce and star in a feature film that portrayed South Asians like myself in an empowered manner, first and foremost. Too often, we see South Asians portrayed in a somewhat subservient manner in Western cinema. My Godmother in Colombo, Nishanthi Perera Pieris, had told me about George Bernard Shaw’s play “The Millionairess”, which was quite progressive in the 1930s, depicting an empowered and thoroughly independent female character. I realized that, by changing the gender and turning the 1930s millionairess into a 21st century billionaire of South Asian descent, I could represent my race in a truly formidable manner. Also, since I grew up watching “My Fair Lady”, which was also adapted from a George Bernard Shaw play, I felt an immense affinity to the kind of language that Shaw utilizes. It was a secondary goal of mine to showcase to the world that a South Asian actor like me could speak the Queen’s English as resplendently and majestically as any Caucasian actor.

What projects do you have coming up?

I am working on adapting an operetta to the big screen, as well as another play which is a more dramatic version of an old fairytale. I wouldn’t be able to produce either project as an independent filmmaker however. I would need to partner with a studio. On a more independent level, I am envisioning a project that might be shot in Sri Lanka, with a big Hollywood actor or actress starring in the film alongside me. Hopefully all of the above comes to fruition.

I have recorded my first album, which will be released in 2021. It was produced by Grammy Award winning musician Hussain Jiffrey, and features Operatic Arias, French and Italian Classical Melodies, as well as Old English Songs from the late 19th century and early 20th century Broadway Musicals. I can’t wait to share this with the world.

Why the movie stresses on Asexuality.

The movie stresses on Asexuality because I myself identify as an Asexual gentleman. This is something which most people are completely unaware of, because so much emphasis is placed on Heterosexuality and Homosexuality. I wanted audiences to become aware of the fact that not everyone likes, needs, or wants sex. I for one, most certainly do not. In THE BILLIONAIRE, for example, the title character whom I portray is attracted to men romantically, but not sexually, which means that none of his relationships are ever consummated – not even after marriage. Since this reflects my own disposition, I felt it was important to showcase to the world at large that two people can fall in love and even get married, but remain essentially pure and chaste. This is a beautiful and sublime thing.

In George Bernard Shaw’s original play ‘The Millionairess’, the title character’s pride and self-worth seemed to derive almost entirely from her wealth and status. I thought this was a rather flimsy characterization, especially in the 21st century, when the Class system is considered somewhat archaic, and so I thought it would be dramatically and psychologically fascinating if my character – THE BILLIONAIRE – drew HIS pride and self-worth as much from his chastity and purity, as he did from his status and wealth. An Asexual person is quasi-angelic, in the sense that such an individual has no desire for a sexual connection with anyone, and I felt this was a much stronger reason for my character to be so proud – above and beyond being rich and upper class.

A lot of people in the LGBTQ community have role models in the media to look up to these days, but Asexual individuals do not have those same role models as yet, unfortunately, and I thought it was high time we changed that.

Life style

Salman Faiz leads with vision and legacy

Salman Faiz has turned his family legacy into a modern sensory empire. Educated in London, he returned to Sri Lanka with a global perspective and a refined vision, transforming the family legacy into a modern sensory powerhouse blending flavours,colours and fragrances to craft immersive sensory experiences from elegant fine fragrances to natural essential oils and offering brand offerings in Sri Lanka. Growing up in a world perfumed with possibility, Aromatic Laboratories (Pvt) Limited founded by his father he has immersed himself from an early age in the delicate alchemy of fragrances, flavours and essential oils.

Salman Faiz did not step into Aromatic Laboratories Pvt Limited, he stepped into a world already alive with fragrance, precision and quiet ambition. Long before he became the Chairman of this large enterprise, founded by his father M. A. Faiz and uncle M.R. Mansoor his inheritance was being shaped in laboratories perfumed with possibility and in conversations that stretched from Colombo to outside the shores of Sri Lanka, where his father forged early international ties, with the world of fine fragrance.

Salman Faiz did not step into Aromatic Laboratories Pvt Limited, he stepped into a world already alive with fragrance, precision and quiet ambition. Long before he became the Chairman of this large enterprise, founded by his father M. A. Faiz and uncle M.R. Mansoor his inheritance was being shaped in laboratories perfumed with possibility and in conversations that stretched from Colombo to outside the shores of Sri Lanka, where his father forged early international ties, with the world of fine fragrance.

Growing up amidst raw materials sourced from the world’s most respected fragrance houses, Salman Faiz absorbed the discipline of formulation and the poetry of aroma almost by instinct. When Salman stepped into the role of Chairman, he expanded the company’s scope from a trusted supplier into a fully integrated sensory solution provider. The scope of operations included manufacturing of flavours, fragrances, food colours and ingredients, essential oils and bespoke formulations including cosmetic ingredients. They are also leading supplier of premium fragrances for the cosmetic,personal care and wellness sectors Soon the business boomed, and the company strengthened its international sourcing, introduced contemporary product lines and extended its footprint beyond Sri Lanka’s borders.

Today, Aromatic Laboratories stands as a rare example of a second generation. Sri Lankan enterprise that has retained its soul while embracing scale and sophistication. Under Salman Faiz’s leadership, the company continues to honour his father’s founding philosophy that every scent and flavour carries a memory, or story,and a human touch. He imbibed his father’s policy that success was measured not by profit alone but the care taken in creation, the relationships matured with suppliers and the trust earned by clients.

“We are one of the leading companies manufacturing fragrances, dealing with imports,exports in Sri Lanka. We customise fragrances to suit specific applications. We also source our raw materials from leading French company Roberte’t in Grasse

Following his father, for Salman even in moments of challenge, he insisted on grace over haste, quality over conveniences and long term vision over immediate reward under Salman Faiz’s stewardship the business has evolved from a trusted family enterprise into a modern sensory powerhouse.

Now the company exports globally to France, Germany, the UK, the UAE, the Maldives and collaborates with several international perfumes and introduces contemporary products that reflect both sophistication and tradition.

We are one of the leading companies. We are one of the leading companies manufacturing fine and industrial fragrance in Sri Lanka. We customise fragrances to suit specific applications said Faiz

‘We also source our raw materials from renowned companies, in Germany, France, Dubai,Germany and many others.Our connection with Robertet, a leading French parfume House in Grasse, France runs deep, my father has been working closely with the iconic French company for years, laying the foundation for the partnership, We continue even today says Faiz”

Today this business stands as a rare example of second generation Sri Lankan entrepreneurship that retains its souls while embracing scale and modernity. Every aroma, every colour and every flavour is imbued with the care, discipline, and vision passed down from father to son – a living legacy perfected under Salmon Faiz’s guidance.

By Zanita Careem

Life style

Home coming with a vision

Harini and Chanaka cultivating change

When Harini and Chanaka Mallikarachchi returned to Sri Lanka after more than ten years in the United States, it wasn’t nostalgia alone that they brought home . It was purpose.Beneath the polished resumes and strong computer science backgrounds lay something far more personal- longing to reconnect with the land, and to give back to the country that shaped their memories. From that quiet but powerful decision was born Agri Vision not just an agricultural venture but a community driven movement grounded in sustainability ,empowerment and heritage. They transform agriculture through a software product developed by Avya Technologies (Pvt Limited) Combining global expertise with a deep love for their homeland, they created a pioneering platform that empowers local farmers and introduce innovative, sustainable solutions to the country’s agri sector.

After living for many years building lives and careers in theUnited States, Harini and Chanaka felt a powerful pull back to their roots. With impressive careers in the computer and IT sector, gaining global experience and expertise yet, despite their success abroad, their hearts remained tied to Sri Lanka – connection that inspired their return where they now channel their technological know-how to advance local agriculture.

For Harini and Chanaka, the visionaries behind Agri Vision are redefining sustainable agriculture in Sri Lanka. With a passion for innovation and community impact, they have built Agri Vision into a hub for advanced agri solutions, blending global expertise with local insight.

In Sri Lanka’s evolving agricultural landscape, where sustainability and authenticity are no longer optional but essential. Harini and Chanaka are shaping a vision that is both rooted and forward looking. In the heart of Lanka’s countryside, Uruwela estate Harini and Chanaka alongside the ever inspiring sister Malathi, the trio drives Agri Vision an initiative that fuses cutting edge technology with age old agricultural wisdom. At the core of their agri philosophy lies two carefully nurtured brands artisan tea and pure cinnamon, each reflecting a commitment to quality, heritage and people.

Armed with global exposure and professional backgrounds in the technology sector,they chose to channel thier experiences into agriculture, believing that true progress begins at home.

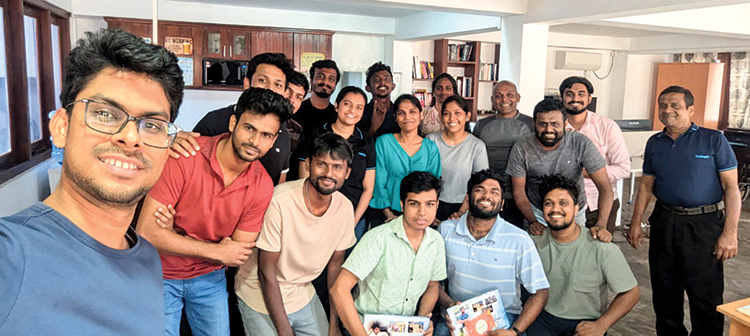

- Avya Technologies (Pvt) ltd software company that developed Agri Vision

- Chanaka,Harini and Shakya Mallikarachchi and Malathi Malathi dias (middle)

But the story of Agri Vision is as much about relationships as it is about technology. Harini with her sharp analytical mind, ensures the operations runs seamlessly Chanaka, the strategist looks outward, connecting Agri Vision to globally best practices and Malathi is their wind behind the wings, ensures every project maintains a personal community focussed ethos. They cultivate hope, opportunity and a blueprint for a future where agriculture serves both the land and the people who depend on it .

For the trio, agriculture is not merely about cultivation, it is about connection. It is about understanding the rhythm of the land, respecting generations of farming knowledge, and that growth is shared by the communities that sustain it. This belief forms the backbone of Agro’s vision, one that places communities not only on the periphery, but at the very heart of every endeavour.

Artisan tea is a celebration of craft and origin sourced from selected growing regions and produced with meticulous attention to detail, the tea embodier purity, traceability and refinement, each leaf is carefully handled to preserve character and flavour, reflecting Sri Lanka’s enduring legacy as a world class tea origin while appealing to a new generation of conscious consumers complementing this is pure Cinnamon, a tribute to authentic Ceylon, Cinnamon. In a market saturated with substitutes, Agri vision’s commitment to genuine sourcing and ethical processing stands firm.

By working closely with cinnamon growers and adhering to traditional harvesting methods, the brands safeguards both quality and cultural heritage.

What truly distinguishes Harini and Chanake’s Agri Vision is their community approach. By building long term partnerships with smallholders. Farmers, the company ensures fair practises, skill development and sustainable livelihoods, These relationships foster trust and resilience, creating an ecosystem where farmers are valued stakeholders in the journey, not just suppliers.

Agri vision integrates sustainable practices and global quality standards without compromising authenticity. This harmony allows Artisan Tea and Pure Cinnamon to resonate beyond borders, carrying with them stories of land, people and purpose.

As the brands continue to grow Harini and Chanaka remain anchored in their founding belief that success of agriculture is by the strength of the communities nurtured along the way. In every leaf of tea and every quill of cinnamon lies a simple yet powerful vision – Agriculture with communities at heart.

By Zanita Careem

Life style

Marriot new GM Suranga

Courtyard by Marriott Colombo has welcomed Suranga Peelikumbura as its new General Manager, ushering in a chapter defined by vision, warmth, and global sophistication.

Suranga’s story is one of both breadth and depth. Over two decades, he has carried the Marriott spirit across continents, from the shimmering luxury of The Ritz-Carlton in Doha to the refined hospitality of Ireland, and most recently to the helm of Resplendent Ceylon as Vice President of Operations. His journey reflects not only international mastery but also a devotion to Sri Lanka’s own hospitality narrative.

What distinguishes Suranga is not simply his credentials but the philosophy that guides him. “Relationships come first, whether with our associates, guests, partners, or vendors. Business may follow, but it is the strength of these connections that defines us.” It is this belief, rooted in both global perspective and local heart, that now shapes his leadership at Courtyard Colombo.

At a recent gathering of corporate leaders, travel partners, and media friends, Suranga paid tribute to outgoing General Manager Elton Hurtis, hon oring his vision and the opportunities he created for associates to flourish across the Marriott world. With deep respect for that legacy, Suranga now steps forward to elevate guest experiences, strengthen community ties, and continue the tradition of excellence that defines Courtyard Colombo.

From his beginnings at The Lanka Oberoi and Cinnamon Grand Colombo to his leadership roles at Weligama Bay Marriott and Resplendent Ceylon, Suranga’s career is a testament to both resilience and refinement. His return to Marriott is not merely a professional milestone, it is a homecoming.

-

Life style2 days ago

Life style2 days agoMarriot new GM Suranga

-

Business23 hours ago

Business23 hours agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoMonks’ march, in America and Sri Lanka

-

Midweek Review6 days ago

Midweek Review6 days agoA question of national pride

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoAutodoc 360 relocates to reinforce commitment to premium auto care

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoWill computers ever be intelligent?

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoThe Rise of Takaichi

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoWetlands of Sri Lanka: