Features

Forty-year saga that can never be forgotten

By Rohan Abeywardena

For the 35th anniversary of The Island five years ago, when our editor Prabath Sahabandu asked me to pen a piece for that issue, I took the opportunity to write about all the hilarious things we did to keep ourselves entertained, while we worked through all types of storms as during much of that period the country was in turmoil with LTTE terror attacks taking place regularly, mainly in the form of suicide bombings that snuffed out innocent lives by the dozens, the JVP’s bloody second uprising and the then government’s counter terror campaign to crush it. We ourselves came very close to peril on more than one occasion after our founder literally vanished into thin air; his newspapers were marked by some of those in power as threats to them. We managed to withstand all that not because we were some heroes, but it was simply a case of us just doing what we had to do in the line of duty.

Last week, when the editor asked me to contribute a column to the 40th anniversary issue, I literally underwent a shock reawakening as to how long it has been since I was among the first few journalists to join this newspaper just about two weeks before it started and a few weeks after the Sunday Island began. In fact, if my now 65-year-old memory serves me right, my first English editorial identity card here bore the legend EE12, indicating that I was the 12th employee to join it. By the time Mr. Upali Wijewardene disappeared with few others who were accompanying him while returning to Colombo on his Learjet from Malaysia in early 1983, our editorial had a formidable team with more than 60 permanent employees, including many veterans and many provincial correspondents, freelancers and even foreign contributors. Of that original lot, I believe only myself, Zanita Careem and Norman Palihawadana still remain here, while many have been claimed by father time and others migrated or are working elsewhere. Both Zanita and Norman have been working throughout at The Island, but I left the newspaper thrice and came back each time, but yet I have put in a total of more than 24 years with the newspaper.

At the time when I first joined The Island in the first week of November 1981, I had been working at the now defunct, staid Sun newspaper of the then powerful Independent Newspaper Group as a sub-editor with Zanita and she followed me to The Island a month or two after me as did many others thereafter. When I joined that former newspaper, I had very high hopes of contributing to combatting wrongs in the society in general, because the newspaper literally shouted from its roof top how independent it was with regular ‘exposures’ with banner headlines. But I soon realised that it was nothing but a charade and started questioning my inner-self as to whose independence that they practised.

At the time when I first joined The Island in the first week of November 1981, I had been working at the now defunct, staid Sun newspaper of the then powerful Independent Newspaper Group as a sub-editor with Zanita and she followed me to The Island a month or two after me as did many others thereafter. When I joined that former newspaper, I had very high hopes of contributing to combatting wrongs in the society in general, because the newspaper literally shouted from its roof top how independent it was with regular ‘exposures’ with banner headlines. But I soon realised that it was nothing but a charade and started questioning my inner-self as to whose independence that they practised.

Some of those at the helm there could have even made Joseph Goebbels blush, for most of their exposures were nothing more than recycled formula type stories as in the celluloid world. Those regularly repeated topics were ‘child labour’, ‘pornography’, illicit abortions, boy prostitution, etc. While the so-called national newspapers kept the country’s intelligentsia generally hoodwinked, the Sinhala language organ of the Communist Party Aththa edited by legendary B.A. Siriwardena (fondly known as Sira) literally went to town, daily exposing corruption and intrigues that were widespread especially among those wielding power and Sira easily wrote the best biting editorial each day among all Sinhala language newspapers. That paper often only had one broad sheet comprising four pages. Even some of those haughty Colombo 07 types who would not want to be seen dead with a Sinhala Commie newspaper, was known to at least read Sira’s blunt down-to-earth editorials, like pinstriped British Bankers reading or ogling at the racy tabloid London SUN hidden inside the broadsheet Financial Times or the Guardian. Of course, unlike the London SUN there was nothing obscene in Sira’s Aththa. It also had formidable cartoonist Jiffrey Yoonoos, who was once slashed with a knife because someone could not stomach his drawings.

The Sun that I worked in and its weekly Weekend were not all about bumming the government in power. There were naturally exceptions like when they took on the then national carrier Air Lanka and its powerful Chairman and Managing Director, the late Capt. Rakhitha Wickramanayake. It was also a treat to read the weekly political column under the pen name Migara written by present Editor of The Sunday Times Sinha Ratnatunga, at a time when the country was starved of inside authentic news.

It was a very good training school for beginners. And I am eternally grateful that I received a good foundation there, especially under the tutelage of Louis Benedict. And many top journalists of today cut their teeth at the old Sun/Weekend.

The straw that broke the camel’s back for me was how The Sun covered the way the UNP storm troopers of the JSS wielding cycle chains and what not broke up the July ’80 general strike. I clearly remember staff photographers coming with photos of battered blood-soaked strikers, who were attacked near Lake House, but the newspaper was more worried about publishing those and antagonising JRJ than reporting the dastardly act. The strikers were simply asking for a Rs 300 salary increase from that regime which came to power with a five-sixths landslide victory in 1977 after making all sorts of promises, including eight pounds of cereals per person per week on top of the existing free rice ration. But after assuming power everything was forgotten and even the existing free rice ration was scrapped. Atop that the self-proclaimed Dharmishta (righteous) regime rolled out the red carpet to capitalist Robber Barons by devaluing the rupee by as much as 43 per cent, eliminated all food subsidies, reduced workers’ rights etc. etc.

I must however state that why I left The Sun and joined a yet to start private newspaper was not because I then had any special illusions about its founder Mr. Upali Wijewardene, except maybe I was attracted to the challenge of working for a man, who was drawing venomous fire from some among the ruling clique, who, I knew, were no angels. However, once the newspaper was started, we all realised that he was a hands-off boss, who gave a free hand to his editor with no interference whatsoever, not even from some of his close relatives. And the editor too was game for a free media culture. In that way, Wijewardene literally opened the floodgates for a truly liberal media culture in this country among national media, which clearly later paved the way for the independent and competitive TV and radio which we enjoy today along with the newspapers and an abusive social media.

I must however state that why I left The Sun and joined a yet to start private newspaper was not because I then had any special illusions about its founder Mr. Upali Wijewardene, except maybe I was attracted to the challenge of working for a man, who was drawing venomous fire from some among the ruling clique, who, I knew, were no angels. However, once the newspaper was started, we all realised that he was a hands-off boss, who gave a free hand to his editor with no interference whatsoever, not even from some of his close relatives. And the editor too was game for a free media culture. In that way, Wijewardene literally opened the floodgates for a truly liberal media culture in this country among national media, which clearly later paved the way for the independent and competitive TV and radio which we enjoy today along with the newspapers and an abusive social media.

When I was called for the sole interview with newpaper’s Editor Vijitha Yapa and Englishman Peter Harland, both had been handpicked by Wijewardene to launch his English newspapers; what really hooked me was the salary that was offered. The interview was not about my competency, but how quickly I could come. One question thatYapa asked me was how much I was drawing at The Sun, when I said I was getting little over Rs 1,200 per month, which was a good salary for a journalist at the time he quickly said: “We’ll give you 1800 a month”. I said I would take it, though I’m sure had I asked for 2000 they would have agreed to it.

What hurt me the most when I left The Sun was the type of departure given to me. Since I felt I was considered just a mediocre, I thought they would be glad to see the back of me, but when I went to give my letter of resignation to editor Rex de Silva, he asked me to give it to the Chairman. But when I went up to the Chairman’s office, I was asked to take a seat and wait and I waited and waited for I believe was well over an hour. Finally, in disgust when I got up to dump my resignation letter with the reception and vanish from there for good, the receptionist said “You can now see the Chairman”. And when I walked into his room and gave the letter all he said was you can go. And that was the treatment meted out to an employee who had taken hardly a day’s leave in the nearly two years he had worked there. But that must be because I must have been the first to join a new rival.

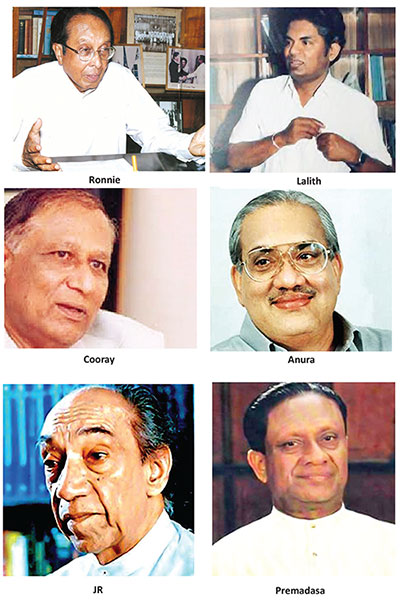

So much happened in those early years of this newspaper that someone should write a book on its history. But I will leave the reader with some interesting personal experiences that must be told. After the sudden disappearance of Wijewardene, it dawned on everyone that we could no longer go on the way it was and we had to sue for peace especially with Finance Minister Ronnie de Mel and our main nemesis, Ranasinghe Premadasa, the then Prime Minister and Minister of Local Government, Housing and Construction and designated successor of JRJ. But Premadasa was paranoid about being usurped by not only Wijewardene, but even by others like Lalith Athulathmudali, Gamini Dissanayake, and he even clashed with Ronnie de Mel. While de Mel was willing to kiss and forget as long as he got good coverage in return from us,Premadasa was not the forgiving or forgetting type.

However, once we got into a fresh scrape with de Mel. It all started with him bashing us in parliament in the worst possible way, most probably after someone provoked him. At the time the late Ajith Samaranayake, probably one of the most talented journalists this country has hitherto produced, acted as editor as Gamini (Gamma to most of us) Weerakoon was abroad. So not to be outdone, Ajith wrote one of the most devastating editorials in reply headlined ‘Barbarians at the gate’ and carried it prominently on page one from top to bottom on left side, not on the usual editorial page. The immediate result was fireworks and I will not go into details except to say banks could have throttled us at the time at the behest of the powerful FM.

Around this time, I had started doing a series of interviews with important political personalities of the day called FIRING LINE. But in order to make peace with Mr. de Mel once again I was ordered to do a weekly interview with him.

Similarly, I learned the hard way why Junius Richard Jayewardene was called the 20th Century Fox. He was a person who never gave any official interviews to any local journalist as long as he was in power. So, when in retirement I thought I could cajole him into speaking out as there was so much blood letting since the signing of the controversial Indo-Lanka Accord of July 1987, for political expediency and there seemed to be no let up with his own party divided and in tatters. Well, I finally did manage to get an appointment for an interview through his Secretary Mr. Mapitigama. At the appointed day and time, I went to his private residence at Ward Place, ‘Braemar’. After a short chat with the head of his security detail SSP Sumith de Silva and Mr. Mapitigama I was ushered into old JRJ’s office and after the initial handshake and my taking a seat opposite him, he at once asked me something like so young man what do you want to talk about? I quickly pulled out my cassette tape recorder and the list of questions.

Now, I must say the secret of my success with the Firing Line series was that I literally ambushed my subjects usually with a below the belt question at the opening bell itself as that almost always resulted in my ‘victim’ virtually eating humble pie after being stunned. With the 20th Century Fox I did not however plan any such stunts but the intention was to soften him up first by pandering to his tastes before trying hard stuff. But lo and behold what I finally got from him was the shock of my career.

The minute I moved to switch on the tape he said stop and to put it away. Then he said, “We’ll first discuss what you want to ask me”. I skipped all formalities and started asking about most of the problems facing the country caused by the UNP often changing the goal post because it wanted to control everything through the imperial presidency of his. But each time I tried to raise an issue from the past he simply shut me up by asking whether I was there and he would say, “You can’t say that because you were not there”.

Most interestingly and ironically the old man was not worried about what was happening to the country, but was repeatedly griping about how much they had suffered by being deprived of their estates by the Land Reforms of the previous United Front government of Bandaranaike. In a way, it explained why he wanted to take revenge from her soon after coming to power.

One thing on which he did make his opinion known to me during that one-sided exchange was that it was wrong of Lalith and Gamini to break away from the party to fight Premadasa. His line of thinking was that they should have worked for change from within.

And finally he said something to the effect “now you got what you came for”, but when I protested that I came there after informing the editor that I am going to interview President Jayewardene and I couldn’t go back and tell him I had no interview. Then he thought for a few seconds and asked me to leave the questions with his secretary.

A few days later, Mapitigama called me and said the President’s answers were ready. I quickly drove to ‘Braemar’, collected it without even bothering to look at what was inside the closed envelope and rushed back to the office thinking I was on top of the world with an exclusive interview with the ex-President.

But when I went through it, I found that what he had answered were not the questions I had given; they were either reworded or totally new questions to fit JRJ’s agenda. When I suggested to then editor Gamini Weerakoon we throw it away and forget about it, the boss however laughed and asked me to carry it.

Another interesting experience I had was when I went to do a Firing Line interview with the late Anura Bandaranaike at his Rosmead Place residence when he was the Leader of the Opposition during President Premadasa’s tenure. Bandaranaike being a formidable debater with the gift of the gab I had no intention of giving him any kid glove treatment even though I then literally worked for his uncle Dr. Seevali Ratwatte, who was our Chairman at the time.

Now, I had been battling Premadasa for a long time in my own way, so at the opening bell I asked Bandaranaike how he hoped to defeat Premadasa when the latter got up as early as 3:00 am and began attending to his work at 4:00 am, whereas the Leader of the Opposition usually got up long past noon after enjoying the good life into the early hours of the morning. The question blew a fuse inside him and the burly giant got up, shoving the coffee table that was there between us, at me. Luckily, I was able to jump back. But soon he realised his blunder and recovered his composure and said he didn’t have to work so hard or something to that effect. But I am sure I had the better of him in the ensuing interview.

Over the particular interview I had no problem back at UNL. In fact, the late Dr. Ratwatte was a gem of a boss when dealing with journalists like me. There was a real incident later on when I wrote a story about some local consultants hired by the World Bank to prepare feasibility studies to help start various business ventures, and took it for a ride. Having spent a couple of million dollars or more on the project, the WB found most of those feasibility studies were either frivolous or redundant. For they were about how to start a successful bakery business, a laundry, beauty salon, etc.

When the newspaper hit the market with that story one of the consultants concerned immediately phoned and demanded a correction, but point blank I refused. The result was that this highly qualified guy, being a Bandaranaike, came to teach me a lesson after telling me so by rushing to our Chairman. The minute he arrived in Dr Ratwatte’s office I got a call from the head office saying the Chairman wanted to see me. In fact, I saw this guy driving into the UNL compound in an Alfa Romeo. I immediately armed myself with something that I was able to surprise him with. So, when Dr Ratwatte asked me ‘Rohan what is all this’? I showed everyone a copy of the internal World Bank critical assessment. But before I could even open it the Chairman just said, ‘Okay, okay you can go back’.

Then there was also a Firing Line Interview that didn’t go beyond a few questions with Bulathsinhalage Sirisena Cooray, one-time strongman under Premadasa. So, some time after the latter’s assassination and after he was distanced by both the UNP and the Premadasa family I asked Cooray for an interview to tell his side of the story as he was being maligned by many. When he agreed for an interview, I got myself dropped at his then residence at Lake Drive close to McDonald’s, Rajagiriya, and asked the driver to pick me up later on his way back after dropping several others.

One of my planned line of attacks was to nail him about his dealings with the underworld characters, like Soththi Upali. So, when I came to the subject of how he came to know Soththi Upali, and no sooner had Cooray told me ‘oya lamaya’ [Soththi Upali] used to drop into see him in connection with Gam Udawa work, than he realised the trap was being laid to corner him; he immediately told me to leave. By that time, I believe Soththi Upali had already been killed by his enemies. But since there was no sign of my vehicle and though the distance from his residence to MacDonald’s Junction wouldn’t have been more than 150 metres, but it felt as if it was the longest walk I had ever undertaken and unlike today Lake Drive was then generally deserted.

My luck with ‘Firing Line’ however, was soon running out with my potential subjects/victims soon getting wise to my shock therapy and some of them even pitched into me on flimsy excuses even before I could open my mouth at an interview.

I believe one of the first to try that counter shock strategy on me was the late TULF Leader M. Sivasithamparam, who succeeded as the TULF Leader after the Tiger hit team assassinated A. Amirthalingam. So, when I went to interview him for ‘Firing Line’, I knew he was no spring chicken as he was a veteran politician and a formidable lawyer. When I got to his place, close to Thimbirigasyaya Junction, I got a shelling from the man accusing me of keeping him waiting for about two hours. That lecture of his about being punctual and not wasting other people’s time would have taken a good 15 minutes. But I was quite sure the appointment I made was for around 10:30, but he insisted it was two hours earlier, or something to that effect.

Features

Building on Sand: The Indian market trap

(Part III in a series on Sri Lanka’s tourism stagnation.)

Every SLTDA (Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority) press release now leads with the same headline: India is Sri Lanka’s “star market.” The numbers seem to prove it, 531,511 Indian arrivals in 2025, representing 22.5% of all tourists. Officials celebrate the “half-million milestone” and set targets for 600,000, 700,000, more.

Every SLTDA (Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority) press release now leads with the same headline: India is Sri Lanka’s “star market.” The numbers seem to prove it, 531,511 Indian arrivals in 2025, representing 22.5% of all tourists. Officials celebrate the “half-million milestone” and set targets for 600,000, 700,000, more.

But follow the money instead of the headcount, and a different picture emerges. We are building our tourism recovery on a low-spending, short-stay, operationally challenging segment, without any serious strategy to transform it into a high-value market. We have confused market size with market quality, and the confusion is costing us billions.

Per-day spending: While SLTDA does not publish market-specific daily expenditure data, industry operators and informal analyses consistently report Indian tourists in the $100-140 per day range, compared to $180-250 for Western European and North American markets.

The math is brutal and unavoidable: one Western European tourist generates the revenue of 3-4 Indian tourists. Building tourism recovery primarily on the low-yield segment is strategically incoherent, unless the goal is arrivals theater rather than economic contribution.

Comparative Analysis: How Competitors Handle Indian Outbound Tourism

India is not unique to Sri Lanka. Indian outbound tourism reached 30.23 million departures in 2024, an 8.4% year-on-year increase, driven by a growing middle class with disposable income. Every competitor destination is courting this market.

This is not diversification. It is concentration risk dressed up as growth.

How did we end up here? Through a combination of policy laziness, proximity bias, and refusal to confront yield trade-offs.

1. Proximity as Strategy Substitute

India is next door. Flights are short (1.5-3 hours), frequent, and cheap. This makes India the easiest market to attract, low promotional cost, high visibility, strong cultural and linguistic overlap. But easiest is not the same as best.

Tourism strategy should optimize for yield-adjusted effort. Yes, attracting Europeans requires longer promotional cycles, higher marketing spend, and sustained brand-building. But if each European generates 3x the revenue of an Indian tourist, the return on investment is self-evident.

We have chosen ease over effectiveness, proximity over profitability.

2. Visa Policy as Blunt Instrument

3. Failure to Develop High-Value Products for Indian Market

There are segments of Indian outbound tourism that spend heavily:

* Wedding tourism: Indian destination weddings can generate $50,000-200,000+ per event

* Wellness/Ayurveda tourism: High-net-worth Indians seek authentic wellness experiences and will pay premium rates

* MICE tourism: Corporate events, conferences, incentive travel

Sri Lanka has these assets—coastal venues for weddings, Ayurvedic heritage, colonial hotels suitable for corporate events. But we have not systematically developed and marketed these products to high-yield Indian segments.

For the first time in 2025, Sri Lanka conducted multi-city roadshows across India to promote wedding tourism. This is welcome—but it is 25 years late. The Maldives and Mauritius have been curating Indian wedding and MICE tourism for decades, building specialised infrastructure, training staff, and integrating these products into marketing.

We are entering a mature market with no track record, no specialised infrastructure, and no price positioning that signals premium quality.

4. Operational Challenges and Quality Perceptions

Indian tourists, particularly budget segments, present operational challenges:

* Shorter stays mean higher turnover, more check-ins, more logistical overhead per dollar of revenue

* Price sensitivity leads to aggressive bargaining, complaints over perceived overcharging

* Large groups (families, wedding parties) require specialised handling

None of these are insurmountable, but they require investment in training, systems, and service design. Sri Lanka has not made these investments systematically. The result: operators report higher operational costs per Indian guest while generating lower revenue, a toxic margin squeeze.

Additionally, Sri Lanka’s positioning as a “budget-friendly” destination reinforces price expectations. Indians comparing Sri Lanka to Thailand or Malaysia see Sri Lanka as cheaper, not better. We compete on price, not value, a race to the bottom.

The Strategic Error: Mistaking Market Size for Market Fit

India’s outbound tourism market is massive, 30 million+ and growing. But scale is not the same as fit.

Market size ≠ market value: The UAE attracts 7.5 million Indians, but as a high-yield segment (business, luxury shopping, upscale hospitality). Saudi Arabia attracts 3.3 million—but for religious pilgrimage with high per-capita spending and long stays.

Thailand attracts 1.8 million Indians as part of a diversified 35-million-tourist base. Indians represent 5% of Thailand’s mix. Sri Lanka has made Indians 22.5% of our mix, 4.5 times Thailand’s concentration, while generating a fraction of Thailand’s revenue.

This reveals the error. We have prioritised volume from a market segment without ensuring the segment aligns with our value proposition.

These needs are misaligned. Indians seek budget value; Sri Lanka needs yield. Indians want short trips; Sri Lanka needs extended stays. Indians are price-sensitive; Sri Lanka needs premium segments to fund infrastructure.

We have attracted a market that does not match our strategic needs—and then celebrated the mismatch as success.

The Way Forward: From Dependency to Diversification

Fixing the Indian market trap requires three shifts: curation, diversification, and premium positioning.

First

, segment the Indian market and target high-value niches explicitly:

, segment the Indian market and target high-value niches explicitly:

* Wedding tourism: Develop specialised wedding venues, train planners, create integrated packages ($50k+ per event)

* Wellness tourism: Position Sri Lanka as authentic Ayurveda destination for high-net-worth health seekers

* MICE tourism: Target Indian corporate incentive travel and conferences

* Spiritual/religious tourism: Leverage Buddhist and Hindu heritage sites with premium positioning

Market these high-value niches aggressively. Let budget segments self-select out through pricing signals.

Second

, rebalance market mix toward high-yield segments:

* Increase marketing spend on Western Europe, North America, and East Asian premium segments

* Develop products (luxury eco-lodges, boutique heritage hotels, adventure tourism) that appeal to high-yield travelers

* Use visa policy strategically, maintain visa-free for premium markets, consider tiered visa fees or curated visa schemes for volume markets

Third

, stop benchmarking success by Indian arrival volumes. Track:

* Revenue per Indian visitor

* Indian market share of total revenue (not arrivals)

* Yield gap: Indian revenue vs. other major markets

If Indians are 22.5% of arrivals but only 15% of revenue, we have a problem. If the gap widens, we are deepening dependency on a low-yield segment.

Fourth

, invest in Indian market quality rather than quantity:

* Train staff on Indian high-end expectations (luxury service standards, dietary needs)

* Develop bilingual guides and materials (Hindi, Tamil)

* Build partnerships with premium Indian travel agents, not budget consolidators

We should aim to attract 300,000 Indians generating $1,500 per trip (through wedding, wellness, MICE targeting), not 700,000 generating $600 per trip. The former produces $450 million; the latter produces $420 million, while requiring more than twice the operational overhead and infrastructure load.

Fifth

, accept the hard truth: India cannot and should not be 30-40% of our market mix. The structural yield constraints make that model non-viable. Cap Indian arrivals at 15-20% of total mix and aggressively diversify into higher-yield markets.

This will require political courage, saying “no” to easy volume in favour of harder-won value. But that is what strategy means: choosing what not to do.

The Dependency Trap

Every market concentration creates path dependency. The more we optimize for Indian tourists, visa schemes, marketing, infrastructure, pricing, the harder it becomes to attract high-yield markets that expect different value propositions.

Hotels that compete on price for Indian segments cannot simultaneously position as luxury for European segments. Destinations known for “affordability” struggle to pivot to premium. Guides trained for high-turnover, short-stay groups do not develop the deep knowledge required for extended cultural tours.

We are locking in a low-yield equilibrium. Each incremental Indian arrival strengthens the positioning as a “budget-friendly” destination, which repels high-yield segments, which forces further volume-chasing in price-sensitive markets. The cycle reinforces itself.

Breaking the cycle requires accepting short-term pain—lower arrival numbers—for long-term gain—higher revenue, stronger positioning, sustainable margins.

The Hard Question

Is Sri Lanka willing to attract two million tourists generating $5 billion, or three million tourists generating $4 billion?

The current trajectory is toward the latter, more arrivals, less revenue, thinner margins, greater fragility. We are optimizing for metrics that impress press releases but erode economic contribution.

The Indian market is not the problem. The problem is building tourism recovery primarily on a low-yield segment without strategies to either transform that segment to high-yield or balance it with high-yield markets.

We are building on sand. The foundation will not hold.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT, Malabe. The views and opinions expressed in this article are personal.)

Features

Digital transformation in the Global South

Understanding Sri Lanka through the India AI Impact Summit 2026

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has rapidly moved from being a specialised technological field into a major social force that shapes economies, cultures, governance, and everyday human life. The India AI Impact Summit 2026, held in New Delhi, symbolised a significant moment for the Global South, especially South Asia, because it demonstrated that artificial intelligence is no longer limited to advanced Western economies but can also become a development tool for emerging societies. The summit gathered governments, researchers, technology companies, and international organisations to discuss how AI can support social welfare, public services, and economic growth. Its central message was that artificial intelligence should be human centred and socially useful. Instead of focusing only on powerful computing systems, the summit emphasised affordable technologies, open collaboration, and ethical responsibility so that ordinary citizens can benefit from digital transformation. For South Asia, where large populations live in rural areas and resources are unevenly distributed, this idea is particularly important.

People friendly AI

One of the most important concepts promoted at the summit was the idea of “people friendly AI.” This means that artificial intelligence should be accessible, understandable, and helpful in daily activities. In South Asia, language diversity and economic inequality often prevent people from using advanced technology. Therefore, systems designed for local languages, and smartphones, play a crucial role. When a farmer can speak to a digital assistant in Sinhala, Tamil, or Hindi and receive advice about weather patterns or crop diseases, technology becomes practical rather than distant. Similarly, voice based interfaces allow elderly people and individuals with limited literacy to use digital services. Affordable mobile based AI tools reduce the digital divide between urban and rural populations. As a result, artificial intelligence stops being an elite instrument and becomes a social assistant that supports ordinary life.

Transformation in education sector

The influence of this transformation is visible in education. AI based learning platforms can analyse student performance and provide personalised lessons. Instead of all students following the same pace, weaker learners receive additional practice while advanced learners explore deeper material. Teachers are able to focus on mentoring and explanation rather than repetitive instruction. In many South Asian societies, including Sri Lanka, education has long depended on memorisation and private tuition classes. AI tutoring systems could reduce educational inequality by giving rural students access to learning resources, similar to those available in cities. A student who struggles with mathematics, for example, can practice step by step exercises automatically generated according to individual mistakes. This reduces pressure, improves confidence, and gradually changes the educational culture from rote learning toward understanding and problem solving.

Healthcare is another area where AI is becoming people friendly. Many rural communities face shortages of doctors and medical facilities. AI-assisted diagnostic tools can analyse symptoms, or medical images, and provide early warnings about diseases. Patients can receive preliminary advice through mobile applications, which helps them decide whether hospital visits are necessary. This reduces overcrowding in hospitals and saves travel costs. Public health authorities can also analyse large datasets to monitor disease outbreaks and allocate resources efficiently. In this way, artificial intelligence supports not only individual patients but also the entire health system.

Agriculture, which remains a primary livelihood for millions in South Asia, is also undergoing transformation. Farmers traditionally rely on seasonal experience, but climate change has made weather patterns unpredictable. AI systems that analyse rainfall data, soil conditions, and satellite images can predict crop performance and recommend irrigation schedules. Early detection of plant diseases prevents large-scale crop losses. For a small farmer, accurate information can mean the difference between profit and debt. Thus, AI directly influences economic stability at the household level.

Employment and communication reshaped

Artificial intelligence is also reshaping employment and communication. Routine clerical and repetitive tasks are increasingly automated, while demand grows for digital skills, such as data management, programming, and online services. Many young people in South Asia are beginning to participate in remote work, freelancing, and digital entrepreneurship. AI translation tools allow communication across languages, enabling businesses to reach international customers. Knowledge becomes more accessible because information can be summarised, translated, and explained instantly. This leads to a broader sociological shift: authority moves from tradition and hierarchy toward information and analytical reasoning. Individuals rely more on data when making decisions about education, finance, and career planning.

Impact on Sri Lanka

The impact on Sri Lanka is especially significant because the country shares many social and economic conditions with India and often adopts regional technological innovations. Sri Lanka has already begun integrating artificial intelligence into education, agriculture, and public administration. In schools and universities, AI learning tools may reduce the heavy dependence on private tuition and help students in rural districts receive equal academic support. In agriculture, predictive analytics can help farmers manage climate variability, improving productivity and food security. In public administration, digital systems can speed up document processing, licensing, and public service delivery. Smart transportation systems may reduce congestion in urban areas, saving time and fuel.

Economic opportunities are also expanding. Sri Lanka’s service based economy and IT outsourcing sector can benefit from increased global demand for digital skills. AI-assisted software development, data annotation, and online service platforms can create new employment pathways, especially for educated youth. Small and medium entrepreneurs can use AI tools to design products, manage finances, and market services internationally at low cost. In tourism, personalised digital assistants and recommendation systems can improve visitor experiences and help small businesses connect with travellers directly.

Digital inequality

However, the integration of artificial intelligence also raises serious concerns. Digital inequality may widen if only educated urban populations gain access to technological skills. Some routine jobs may disappear, requiring workers to retrain. There are also risks of misinformation, surveillance, and misuse of personal data. Ethical regulation and transparency are, therefore, essential. Governments must develop policies that protect privacy, ensure accountability, and encourage responsible innovation. Public awareness and digital literacy programmes are necessary so that citizens understand both the benefits and limitations of AI systems.

Beyond economics and services, AI is gradually influencing social relationships and cultural patterns. South Asian societies have traditionally relied on hierarchy and personal authority, but data-driven decision making changes this structure. Agricultural planning may depend on predictive models rather than ancestral practice, and educational evaluation may rely on learning analytics instead of examination rankings alone. This does not eliminate human judgment, but it alters its basis. Societies increasingly value analytical thinking, creativity, and adaptability. Educational systems must, therefore, move beyond memorisation toward critical thinking and interdisciplinary learning.

AI contribution to national development

In Sri Lanka, these changes may contribute to national development if implemented carefully. AI-supported financial monitoring can improve transparency and reduce corruption. Smart infrastructure systems can help manage transportation and urban planning. Communication technologies can support interaction among Sinhala, Tamil, and English speakers, promoting social inclusion in a multilingual society. Assistive technologies can improve accessibility for persons with disabilities, enabling broader participation in education and employment. These developments show that artificial intelligence is not merely a technological innovation but a social instrument capable of strengthening equality when guided by ethical policy.

Symbolic shift

Ultimately, the India AI Impact Summit 2026 represents a symbolic shift in the global technological landscape. It indicates that developing nations are beginning to shape the future of artificial intelligence according to their own social needs rather than passively importing technology. For South Asia and Sri Lanka, the challenge is not whether AI will arrive but how it will be used. If education systems prepare citizens, if governments establish responsible regulations, and if access remains inclusive, AI can become a partner in development rather than a source of inequality. The future will likely involve close collaboration between humans and intelligent systems, where machines assist decision making while human values guide outcomes. In this sense, artificial intelligence does not replace human society, but transforms it, offering Sri Lanka an opportunity to build a more knowledge based, efficient, and equitable social order in the decades ahead.

by Milinda Mayadunna

Features

Governance cannot be a postscript to economics

The visit by IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva to Sri Lanka was widely described as a success for the government. She was fulsome in her praise of the country and its developmental potential. The grounds for this success and collaborative spirit go back to the inception of the agreement signed in March 2023 in the aftermath of Sri Lanka’s declaration of international bankruptcy. The IMF came in to fulfil its role as lender of last resort. The government of the day bit the bullet. It imposed unpopular policies on the people, most notably significant tax increases. At a moment when the country had run out of foreign exchange, defaulted on its debt, and faced shortages of fuel, medicine and food, the IMF programme restored a measure of confidence both within the country and internationally.

Since 1965 Sri Lanka has entered into agreements with the IMF on 16 occasions none of which were taken to their full term. The present agreement is the 17th agreement . IMF agreements have traditionally been focused on economic restructuring. Invariably the terms of agreement have been harsh on the people, with priority being given to ensure the debtor country pays its loans back to the IMF. Fiscal consolidation, tax increases, subsidy reductions and structural reforms have been the recurring features. The social and political costs have often been high. Governments have lost popularity and sometimes fallen before programmes were completed. The IMF has learned from experience across the world that macroeconomic reform without social protection can generate backlash, instability and policy reversals.

The experience of countries such as Greece, Ireland and Portugal in dealing with the IMF during the eurozone crisis demonstrated the political and social costs of austerity, even though those economies later stabilised and returned to growth. The evolution of IMF policies has ensured that there are two special features in the present agreement. The first is that the IMF has included a safety net of social welfare spending to mitigate the impact of the austerity measures on the poorest sections of the population. No country can hope to grow at 7 or 8 percent per annum when a third of its people are struggling to survive. Poverty alleviation measures in the Aswesuma programme, developed with the agreement of the IMF, are key to mitigating the worst impacts of the rising cost of living and limited opportunities for employment.

Governance Included

The second important feature of the IMF agreement is the inclusion of governance criteria to be implemented alongside the economic reforms. It goes to the heart of why Sri Lanka has had to return to the IMF repeatedly. Economic mismanagement did not take place in a vacuum. It was enabled by weak institutions, politicised decision making, non-transparent procurement, and the erosion of checks and balances. In its economic reform process, the IMF has included an assessment of governance related issues to accompany the economic restructuring process. At the top of this list is tackling the problem of corruption by means of publicising contracts, ensuring open solicitation of tenders, and strengthening financial accountability mechanisms.

The IMF also encouraged a civil society diagnostic study and engaged with civil society organisations regularly. The civil society analysis of governance issues which was promoted by Verite Research and facilitated by Transparency International was wider in scope than those identified in the IMF’s own diagnostic. It pointed to systemic weaknesses that go beyond narrow fiscal concerns. The civil society diagnostic study included issues of social justice such as the inequitable impact of targeting EPF and ETF funds of workers for restructuring and the need to repeal abuse prone laws such as the Prevention of Terrorism Act and the Online Safety Act. When workers see their retirement savings restructured without adequate consultation, confidence in policy making erodes. When laws are perceived to be instruments of arbitrary power, social cohesion weakens.

During a meeting between the IMF Managing Director Georgeiva and civil society members last week, there was discussion on the implementation of those governance measures in which she spoke in a manner that was not alien to the civil society representatives. Significantly, the civil society diagnostic report also referred to the ethnic conflict and the breakdown of interethnic relations that led to three decades of deadly war, causing severe economic losses to the country. This was also discussed at the meeting. Governance is not only about accounting standards and procurement rules. It is about social justice, equality before the law, and political representation. On this issue the government has more to do. Ethnic and religious minorities find themselves inadequately represented in high level government committees. The provincial council system that ensured ethnic and minority representation at the provincial level continues to be in abeyance.

Beyond IMF

The significance of addressing governance issues is not only relevant to the IMF agreement. It is also important in accessing tariff concessions from the European Union. The GSP Plus tariff concession given by the EU enables Sri Lankan exports to be sold at lower prices and win markets in Europe. For an export dependent economy, this is critical. Loss of such concessions would directly affect employment in key sectors such as apparel. The government needs to address longstanding EU concerns about the protection of human rights and labour rights in the country. The EU has, for several years, linked the continuation of GSP Plus to compliance with international conventions. This includes the condition that the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) be brought into line with international standards. The government’s alternative in the form of the draft Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PTSA) is less abusive on paper but is wider in scope and retains the core features of the PTA.

Governance and social justice factors cannot be ignored or downplayed in the pursuit of economic development. If Sri Lanka is to break out of its cycle of crisis and bailout, it must internalise the fact that good governance which promotes social justice and more fairly distributes the costs and fruits of development is the foundation on which durable economic growth is built. Without it, stabilisation will remain fragile, poverty will remain high, and the promise of 7 to 8 percent growth will remain elusive. The implementation of governance reforms will also have a positive effect through the creative mechanism of governance linked bonds, an innovation of the present IMF agreement.

The Sri Lankan think tank Verité Research played an important role in the development of governance linked bonds. They reduce the rate of interest payable by the government on outstanding debt on the basis that better governance leads to a reduction in risk for those who have lent their money to Sri Lanka. This is a direct financial reward for governance reform. The present IMF programme offers an opportunity not only to stabilise the economy but to strengthen the institutions that underpin it. That opportunity needs to be taken. Without it, the country cannot attract investment, expand exports and move towards shared prosperity and to a 7-8 percent growth rate that can lift the country out of its debt trap.

by Jehan Perera

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoReconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoVictor Melder turns 90: Railwayman and bibliophile extraordinary

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoLOVEABLE BUT LETHAL: When four-legged stars remind us of a silent killer

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoVictor, the Friend of the Foreign Press

-

Latest News4 days ago

Latest News4 days agoNew Zealand meet familiar opponents Pakistan at spin-friendly Premadasa

-

Latest News4 days ago

Latest News4 days agoTariffs ruling is major blow to Trump’s second-term agenda

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoECB push back at Pakistan ‘shadow-ban’ reports ahead of Hundred auction