Opinion

English as medium of instruction at Law College

The step the government has taken to introduce English as the medium of instruction in the Law College will definitely ensure the quality of the lawyers produced by the Law College, and it will also increase their employability. It will help them for their higher studies and foreign employment as well. It will boost their image too in the eyes of the public. People would always try to look down upon a lawyer speaking halting English or no English at all.

At present the number of students who study law in the vernacular, that is, Sinhala and Tamil is much higher than the students who study it in English. In my view the arguments of some opposition parliamentarians that the introduction of English as the only medium of instruction in the Law College will discriminate against students from rural areas does not hold water. Foreign Minister Ali Sabry in the parliamentary debate on this effectively quashed their concern by his well posed rhetorical question “if the students from rural areas can study Medicine and Engineering in the English medium even without a pass in O level English, how come the students admitted to the Law College through an entrance examination including an English language test cannot do it?

To enter the law faculties of the conventional universities to study LL.B, a candidate should have a credit pass in O level English. The LL.B holders from the Open University should have completed the Professional Certificate in English course conducted by the Open University to enter the Law College. The candidates who enter the Law College directly have to pass the English language test. Therefore, there is no issue for these three groups of students to follow the Attorney at Law course in the Law College in the English medium as they have already got the basic knowledge of English.

The standard of English of most lawyers who studied law in the vernacular is very poor. These lawyers themselves admit that their English language proficiency is poor and they cannot refer to legal books in English. Nor can they draft documents in English. They cannot go to higher courts for legal practice either. Prospects for foreign employment for them are bleak too.

Why English medium?

If you want to specialise in an area of study, you should first have ample literature in that area of study in the language you know. For instance, when you google for online literature on law in Sinhala or Tamil, you will get a blank screen. When you go to a university library, you will not find any book on law in Sinhala or Tamil. Literally speaking you do not have any literature to read. You have to depend on the notes and handouts your lecturers give you. If your lecturers have a good command of English, then they may refer to English books and translate some study materials for you. If their English is not that much good, you will not have that either.

Translation of Course Materials

cumbersome.

Some argue that if Japanese, Chinese and Koreans can do their higher studies in their languages why we can’t. This is a faulty argument. Literature on any subject is immediately translated into their languages by subject experts and efficient reading materials are readily available for them for reference in their universities. Our situation is different. Even important bills are pending in parliament because their translation is not available in Tamil to be enacted as law. This is our situation. Do we have enough manpower and resources to translate a large number of books from English to local languages? Can we at least translate one eighth of the reading materials available in the Peradeniya University library? What about the quality of the materials translated? Translators should be subject experts with high command of English. I met some students doing LL. B in Tamil in one of our universities. They said their greatest challenge was finding reading materials in Tamil. They said they had access to a very limited amount of reading materials in Tamil and the standard of these materials was questionable too. When the first Prime Minister of Singapore Lee Kuan Yew visited Peradeniya University, he asked then Vice Chancellor, ‘How can three engineers educated in three different languages build one bridge?’ And the VC replied: ‘That, Sir is a political question for the ministers to answer’. Then the Vice Chancellor mentioned that all the basic textbooks which were printed in English had to be translated to Sinhala and Tamil and by the time they were translated and printed, they were three to four editions old. (Source: The Island)

Some English Medium

Courses only in name.

Some English medium courses in higher education institutions exist in name only.

I worked for a National College of Education and nearly half of the academic staff had completed their degrees and post graduate degrees in the English medium but ninety percent of them could not express themselves in English nor could they write simple letters of request like request for leave.

According to them, though they were enrolled for English medium courses, for them most lectures were conducted in Sinhala or Tamil. This had happened for two reasons. One reason was students could not understand English lectures and the other reason was some lecturers could not lecturer in English confidently. The final examination was also conducted in Sinhala or Tamil. Only the academic transcript said they had followed the course in the English medium. Now they have made it compulsory for the candidates following the English medium courses to sit the final examinations in English. English medium degree holders working in government sectors are exempted from the English language requirement for efficiency bar, get a once and for all allowance, an additional increment and additional marks too in promotion interviews, but most of them do not have even working knowledge of English. English medium degree is also a basic qualification to become English instructors in Universities and lecturers in institutions like Technical Colleges. It is good to recruit English medium degree holders to these positions through an English proficiency test not a General knowledge test. Therefore, the English medium courses should maintain their standards. They should not exist only in name.

Though this decision of making English as the only medium of instruction at the Law College was taken by the Legal Council, Foreign Minister Ali Sabry as then Justice Minister played a bigger role in it. I very much appreciate this decision and strongly hope this change will definitely raise the standard of our lawyers and ultimately the standard of our judiciary.

M. A. Kaleel

(Writer is a Senior English Language Teacher Educator and holds an MA in TESOL from the University College of London, University of London. kaleelmohammed757@gmail.com)

Opinion

Future must be won

Excerpts from the speech of the Chairman of the Communist Party of Sri Lanka, D.E.W. Gunasekera, at the 23rd Convention of the Party

This is not merely a routine gathering. Our annual congress has always been a decisive moment in Sri Lanka’s political history. For 83 years, since the formation of our Party in 1943, we have held 22 conventions. Each one reflected the political turning points of our time. Today, as we assemble for the 23rd Congress, we do so at another historic crossroads – amidst a deepening economic crisis at home and profound transformations in the global order.

Our Historical Trajectory: From Anti-imperialism to the Present

The 4th Party Convention in 1950 was a decisive milestone. It marked Sri Lanka’s conscious turn toward anti-imperialism and clarified that the socialist objective and revolution would be a long-term struggle. By the 1950s, the Left movement in Sri Lanka had already socialized the concept of socialist transformation among the masses. But the Communist Party had to dedicate nearly two decades to building the ideological momentum required for an anti-imperialist revolution.

As a result of that consistent struggle, we were able to influence and contribute to the anti-imperialist objectives achieved between 1956 and 1976. From the founding of the Left movement in 1935 until 1975, our principal struggle was against imperialism – and later against neo-imperialism in its modernised forms,

The 5th Convention in 1955 in Akuressa, Matara, adopted the Idirimaga (“The Way Forward”) preliminary programme — a reform agenda intended to be socialised among the people, raising public consciousness and organising progressive forces.

At the 1975 Convention, we presented the programme Satan Maga (“The Path of Battle”).

The 1978 Convention focused on confronting the emerging neoliberal order that followed the open economy reforms.

The 1991 Convention, following the fall of the Soviet Union, grappled with international developments and the emerging global order. We understand the new balance of forces.

The 20th Convention in 2014, in Ratnapura, addressed the shifting global balance of power and the implications for the Global South, including the emergence of a multipolar world. At that time, contradictions were developing between the United People’s Freedom Alliance (UPFA), government led by Mahinda Rajapaksa, and the people, and we warned of these contradictions and flagged the dangers inherent in the trajectory of governance.

Each convention responded to its historical moment. Today, the 23rd must responded to ours.

Sri Lanka in the Global Anti-imperialist Tradition

Sri Lanka was a founding participant in the Bandung Conference of 1955, a milestone in the anti-colonial solidarity of Asia and Africa. In 1976, Sri Lanka hosted the 5th Summit of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) in Colombo, under Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike.

At that time, Fidel Castro emerged as a leading voice within NAM. At the 6th Summit in Havana in 1979, chaired by Castro, a powerful critique was articulated regarding the international economic and social crises confronting newly sovereign nations.

Three central obstacles were identified:

1. The unjust global economic order.

2. The unequal global balance of power,

3. The exploitative global financial architecture.

After 1979, the Non-Aligned Movement gradually weakened in influence. Yet nearly five decades later, those structural realities remain. In fact, they have intensified.

The Changing Global Order: Facts and Realities

Today we are witnessing structural Changes in the world system.

1. The Shift in Economic Gravity

The global economic centre of gravity has shifted toward Asia after centuries of Western dominance. Developing countries collectively represent approximately 85% of the world’s population and roughly 40-45% of global GDP depending on measurement methods.

2. ASEAN and Regional Integration

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), now comprising 10 member states (with Timor-Leste in the accession process), has deepened economic integration. In addition, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) – which includes ASEAN plus China, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand – is widely recognised as the largest free trade agreement in the world by participating economies.

3. BRICS Expansion

BRICS – originally Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – has expanded. As of 2025, full members include Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Ethiopia and Iran. Additional partner countries are associated through BRICS mechanisms.

Depending on measurement methodology (particularly Purchasing Power Parity), BRICS members together account for approximately 45-46% of global GDP (PPP terms) and roughly 45% of the world’s population. If broader partners are included, demographics coverage increases further. lt is undeniably a major emerging bloc.

4. Regional Blocs Across the Global South

Latin America, Africa, Eurasia and Asia have all consolidated regional trade and political groupings. The Global South is no longer politically fragmented in the way it once was.

5. Alternative Development Banks

Two important institutions have emerged as alternatives to the Bretton Woods system:

• The New Development Bank (NDB) was established by BRICS in 2014.

• The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), operational since 2016, now with over 100 approved members.

These institutions do not yet replace the IMF or World Bank but they represent movement toward diversification.

6. Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO)

The SCO has evolved into a major Eurasian security and political bloc, including China, Russia, India. Pakistan and several Central Asian states.

7. Do-dollarization and Reserve Trends

The US dollar remains dominant foreign exchange reserves at approximately 58%, according to IMF data. This share has declined gradually over two decades. Diversification into other currencies and increased gold holdings indicate slow structural shifts.

8. Global North and Global South

The Global North – broadly the United States, Canada European Union and Japan – accounts for roughly 15% of the world’s population and about 35-40% of global GDP.

The Global South – Latin America, Africa, Asia and parts of Eurasia – contains approximately 85% of humanity and an expanding share of global production.

These shifts create objective conditions for the restructuring of the global financial architecture – but they do not automatically guarantee justice.

Sri Lanka’s Triple Crisis

Sri Lanka’s crisis culminated on 12 April 2022, when the government declared suspension of external debt payments – effectively announcing sovereign default.

Since then, political leadership has changed. President Gotabaya Rajapaksa resigned. President Ranil Wickremesinghe governed during the IMF stabilization period. In September 2024, Anura Kumara Dissanayake of the National People’s Power (NPP) was elected President.

We have had three presidents since the crisis began.

Yet four years later, the structural crisis remains unresolved,

‘The crisis had three dimensions:

1. Fiscal crisis – the Treasury ran out of rupees.

2. Foreign exchange crisis – the Central Bank ran out of dollars.

3. Solvency crisis – excessive domestic and external borrowing rendered repayment impossible.

Despite debt suspension, Sri Lanka’s total debt stock – both domestic and external – remains extremely high relative to GDP, External Debt restructuring provides temporary could reappear around 2027-2028 when grace periods taper.

In the Context of global geopolitical competition in the Indian Ocean region, Sri Lanka’s economic vulnerability becomes even more dangerous,

The Central Task: Economic Sovereignty

Therefore, the 23rd Congress must clearly declare that the struggle for economic sovereignty is the principal task before our nation.

Economic sovereignty means:

• Production economy towards industrialization and manufacturing.

• Food and energy security.

• Democratic control of development policy.

• Fair taxation.

• A foreign policy based on non-alignment and national dignity.

Only a centre-left government, rooted in anti-imperialist and nationalist forces, can lead this struggle.

But unity is required and self-criticism.

All progressive movements must engage in honest reflection. Without such reflection, we risk irrelevance. If we fail to build a broad coalition, if we continue Political fragmentation, the vacuum may be filled by extreme right forces. These forces are already growing globally.

Even governments elected on left-leaning mandates can drift rightward under systemic pressure. Therefore, vigilance and organised mass politics are essential.

Comrades,

History does not move automatically toward justice. It moves through organised struggle.

The 23rd Congress of the Communist Party of Sri Lanka must reaffirm.

• Our commitment to socialism.

• Our dedication to anti-imperialism.

• Our strategic clarity in navigating a multipolar world.

• Our resolve to secure economic sovereignty for Sri Lanka.

Let this Congress become a turning point – not merely in rhetoric, but in organisation and action.

The future will not be given to us.

It must be won.

Opinion

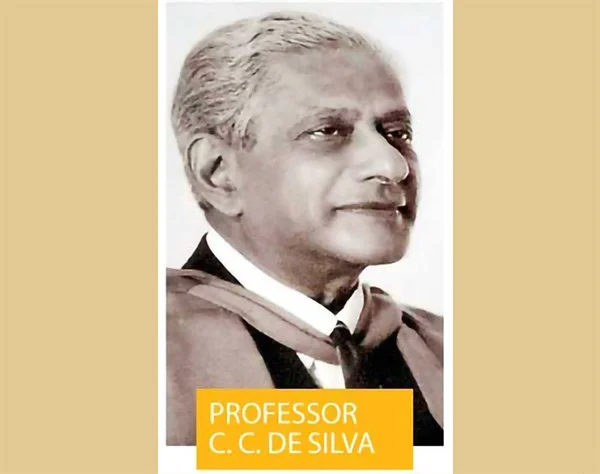

Singular Man: A 122nd Birth Anniversary accolade to Professor C. C. De Silva

On the 25th of February, the 122nd birth anniversary of Emeritus Professor C. C. De Silva, the medical fraternity, as well as the general public, should remember not just the “Godfather of Modern Sri Lankan Paediatrics,” but a unique intellectual whose fantastic brainpower was matched only by his relentless pursuit towards perfection.

To the world, he was a colossus of science. For me, he was a mentor who transformed a raw medical graduate into a disciplined scholar through a “baptism by fire”; indeed, a baptism that I shall cherish forever.

I do hope and pray that this narrative is a sufficiently adequate and descriptive tribute to a persona par excellence, a true titan of the Sri Lankan Medical Landscape.

From Scepticism to Admiration

Our first encounter in 1969 was, quite strangely and perhaps humorously, a lesson to me on my own youthful ignorance and audacity. As a fourth-year medical student, I watched a grey-haired gentleman in the front row challenge an erudite foreign guest lecturer with questions: queries which I considered to be “irrelevant”. I dismissed him then as a “spent old force”. On inquiry, I was told that the person was Professor C. C. De Silva, who had just retired. I quietly thought to myself, “Thank God for small mercies, as I would not be taught by someone like him.”

God forbid, too, as to how terribly wrong I was. Years later, I realised that those questions were the hallmark of a visionary and a dedicated pedagogic academic celebrity, intensely relevant to the health of the children of our beloved Motherland. They were totally and far above the head and intellect of a “raw” medical student. Thankfully, it was not long before, this dignitary, whom I had the bravado to call “a spent old force”, became one of the most influential and gravitational forces in my professional life.

The Seven-Fold Refinement

The true turning point came in 1971. Under the guidance of Dr M. C. J. Hunt, the Consultant Paediatrician at Lady Ridgeway Hospital, under whom I did the second six months of Pre-Registration Internship, I was forced by my “Boss”, terminology used at that time to describe the Consultants, to write my very first scientific paper on a very rare and esoteric condition. When it was submitted to the Ceylon Journal of Child Health, its Editor, Dr Stella De Silva, sent it to a reviewer for assessment. Impudently armed with my “masterpiece”, I jauntily presented myself at the residence of Emeritus Professor C. C. De Silva, who was allocated to be the reviewer of my creation.

What followed was a merciless masterclass in fantastic academic expertise. With a sharp mind and an even sharper red pen, Professor C. C. De Silva took my handiwork completely apart. He cut, chopped, and rearranged the text until barely a sentence of my original prose remained. Over several weeks, this “torture” was repeated no less than seven times. Each week, I would return with a retyped manuscript, only to have it bled dry, again and again, by his uncompromisingly erudite brain. It was indeed a “Baptism by fire“.

Yet for all this, there was absolute grace in his rigour. The man was so exacting in academic literary work that nothing, nothing at all, escaped his eagle’s eye. Each session ended with a delicious high tea served by his gracious wife, and the parting words: “My boy, you do have a lot to learn”.

By the eighth attempt, the paper that had originally been a raw, uncut nugget was finally polished into a veritable gem. The journal published it, and it was my very first scientific publication. However, much more importantly, it was the occasion when I learned the compelling truth of Rabindranath Tagore’s immortal words, “Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards perfection“. It clearly impressed on me the fact that for intellectuals like Professor C. C. De Silva, it was a compelling intonation.

An Unending Legacy

Professor C. C. De Silva was definitely much more than just an academic; he was the personification of British English at its finest and a scientist with an obsessive craving for detail. Later, he became a father figure to me, even attending my presentations and offering gentle constructive criticisms, which eventually moved yours truly from fearing it to desperately craving for it.

In 1987, in a final act of characteristic generosity, he asked for my Curriculum Vitae to nominate me for the Fellowship of the Royal College of Physicians of London, UK. I was just 40 years of age. Though the Great Leveller took him from us before his letter to the Royal College of Physicians could be posted, his belief in me was the ultimate validation of my academic progress.

The Good Professor left a heritage of refinement and scholastic brilliance that was hard to match. Following his demise in 1987, the Sri Lanka Paediatric Association, which later became the Sri Lanka College of Paediatricians, established an Annual Professor C. C. De Silva Memorial Oration. I was greatly honoured but profoundly humbled to be competitively selected to deliver that oration, not just once, but three times, in 1991, 1999, and 2008, on three different scientific technical topics based on my research endeavours. Those were three of the highest compliments that I have ever received in my professional life.

The Singular Man

Today, as we mark 122 years since his birth, the shadow of Professor C. C. De Silva still looms ever so large over the Lady Ridgeway Hospital for Children. He taught us that in medicine, “good enough” is never enough; it simply has to be the “best”. He was a caring and vibrant soul who demanded the best because he believed his students and his patients deserved nothing less.

I remain as one of a singularly fortunate cluster that had the extraordinary privilege of walking along a pathway lit by this great man. He was a fabulous leading torch-bearer who guided us in our professional lives. I was always that much richer for the time that I spent in his ever-so-valued company.

Emeritus Professor Cholmondeley Chalmers De Silva: My dear Sir, we will never forget you. This tribute is for a classy scholar, a superb mentor, a master craftsman, and most definitely, an extraordinary man like no other. Today, WE DEVOTEDLY SALUTE YOU and wish you HAPPY BIRTHDAY, in your heavenly abode.

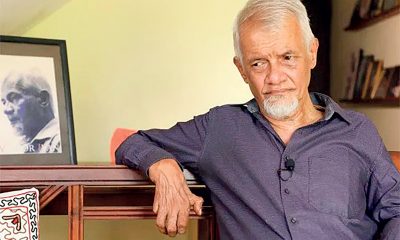

by Dr B. J. C. Perera

MBBS(Cey), DCH(Cey), DCH(Eng), MD(Paediatrics), MRCP(UK), FRCP(Edin), FRCP(Lond), FRCPCH(UK), FSLCPaed, FCCP, Hony. FRCPCH(UK), Hony. FCGP(SL)

Specialist Consultant Paediatrician and Honorary Senior Fellow, Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Opinion

Why so unbuddhist?

Hardly a week goes by, when someone in this country does not preach to us about the great, long lasting and noble nature of the culture of the Sinhala Buddhist people. Some Sundays, it is a Catholic priest that sings the virtues of Buddhist culture. Some eminent university professor, not necessarily Buddhist, almost weekly in this newspaper, extols the superiority of Buddhist values in our society. Some 70 percent of the population in this society, at Census, claim that they are Buddhist in religion. They are all capped by that loud statement in dhammacakka pavattana sutta, commonly believed to have been spoken by the Buddha to his five colleagues, when all of them were seeking release from unsatisfactory state of being:

‘….jati pi dukkha jara pi dukkha maranam pi dukkham yam pi…. sankittena…. ‘

If birth (‘jati’) is a matter of sorrow, why celebrate birth? Not just about 2,600 years ago but today, in distant port city Colombo? Why gaba perahara to celebrate conception? Why do bhikkhu, most prominent in this community, celebrate their 75th birthday on a grand scale? A commentator reported that the Buddha said (…ayam antima jati natthi idani punabbhavo – this is my last birth and there shall be no rebirth). They should rather contemplate on jati pi dukkha and anicca (subject to change) and seek nibbana, as they invariably admonish their listeners (savaka) to do several times a week. (Incidentally, Buddhists acquire knowledge by listening to bhanaka. Hence savaka and bhanaka.) The incongruity of bhikkhu who preach jati pi duklkha and then go to celebrate their 65th birthday is thunderous.

For all this, we are one of the most violent societies in the world: during the first 15 days of this year (2026), there has been more one murder a day, and just yesterday (13 February) a youngish lawyer and his wife were gunned down as they shopped in the neighbourhood of the Headquarters of the army. In 2022, the government of this country declared to the rest of the world that it could not pay back debt it owed to the rest of the world, mostly because those that governed us plundered the wealth of the governed. For more than two decades now, it has been a public secret that politicians, bureaucrats, policemen and school teachers, in varying degrees of culpability, plunder the wealth of people in this country. We have that information on the authority of a former President of the Republic. Politicians who held the highest level of responsibility in government, all Buddhist, not only plundered the wealth of its citizens but also transferred that wealth overseas for exclusive use by themselves and their progeny and the temporary use of the host nation. So much for the admonition, ‘raja bhavatu dhammiko’ (may the king-rulers- be righteous). It is not uncommon for politicians anywhere to lie occasionally but ours speak the truth only more parsimoniously than they spend the wealth they plundered from the public. The language spoken in parliament is so foul (parusa vaca) that galleries are closed to the public lest school children adopt that ‘unparliamentary’ language, ironically spoken in parliament. If someone parses the spoken and written word in our society, there is every likelihood that he would find that rumour (pisuna vaca) is the currency of the realm. Radio, television and electronic media have only created massive markets for lies (musa vada), rumour (pisuna vaca), foul language (parusa vaca) and idle chatter (samppampalapa). To assure yourself that this is true, listen, if you can bear with it, newscasts on television, sit in the gallery of Parliament or even read some latterday novels. There generally was much beauty in what Wickremasinghe, Munidasa, Tennakone, G. B. Senanayake, Sarachchandra and Amarasekara wrote. All that beauty has been buried with them. A vile pidgin thrives.

Although the fatuous chatter of politicians about financial and educational hubs in this country have wafted away leaving a foul smell, it has not taken long for this society to graduate into a narcotics hub. In 1975, there was the occasional ganja user and he was a marginal figure who in the evenings, faded into the dusk. Fifty years later, narcotics users are kingpins of crime, financiers and close friends of leading politicians and otherwise shakers and movers. Distilleries are among the most profitable enterprises and leading tax payers and defaulters in the country (Tax default 8 billion rupees as of 2026). There was at least one distillery owner who was a leading politician and a powerful minister in a long ruling government. Politicians in public office recruited and maintained the loyalty to the party by issuing recruits lucrative bar licences. Alcoholic drinks (sura pana) are a libation offered freely to gods that hold sway over voters. There are innuendos that strong men, not wholly lay, are not immune from seeking pleasures in alcohol. It is well known that many celibate religious leaders wallow in comfort on intricately carved ebony or satin wood furniture, on uccasayana, mahasayana, wearing robes made of comforting silk. They do not quite observe the precept to avoid seeking excessive pleasures (kamasukhallikanuyogo). These simple rules of ethical behaviour laid down in panca sila are so commonly denied in the everyday life of Buddhists in this country, that one wonders what guides them in that arduous journey, in samsara. I heard on TV a senior bhikkhu say that bhikkhu sangha strives to raise persons disciplined by panca sila. Evidently, they have failed.

So, it transpires that there is one Buddhism in the books and another in practice. Inquiries into the Buddhist writings are mainly the work of historians and into religion in practice, the work of sociologists and anthropologists. Many books have been written and many, many more speeches (bana) delivered on the religion in the books. However, very, very little is known about the religion daily practised. Yes, there are a few books and papers written in English by cultural anthropologists. Perhaps we know more about yakku natanava, yakun natanava than we know about Buddhism is practised in this country. There was an event in Colombo where some archaeological findings, identified as dhatu (relics), were exhibited. Festivals of that nature and on a grander scale are a monthly regular feature of popular Buddhism. How do they fit in with the religion in the books? Or does that not matter? Never the twain shall meet.

by Usvatte-aratchi

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoReconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoVictor Melder turns 90: Railwayman and bibliophile extraordinary

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoLOVEABLE BUT LETHAL: When four-legged stars remind us of a silent killer

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoVictor, the Friend of the Foreign Press

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoNew Zealand meet familiar opponents Pakistan at spin-friendly Premadasa

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoTariffs ruling is major blow to Trump’s second-term agenda

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoECB push back at Pakistan ‘shadow-ban’ reports ahead of Hundred auction