Features

Drafting an amendment to the Order in Council and hosting a Commonwealth Conference

Excerpted from Memoirs of a Cabinet Secretary by BP Peiris

During the latter half of 1948, while holding the post of Assistant Secretary to the Cabinet, I was appointed as Secretary to the Commission on the Amendment of the Ceylon Constitution Order in Council. The members of the Commission were the Hon. L. A. Rajapakse, H. V. Perera, K. C., Sir Ivor Jennings, E. A. P. Wijeratne, G. G. Ponnambalam and J. A. Maartensz.

With so many legal brains on the Commission, I found the discussions most interesting. It was my first experience in a secretarial capacity to a Commission. My duty, as Secretary, was first to find a place at which to hold our meetings. The President of the Senate was kind enough to place one of the Senate Committee Rooms at our disposal, and meetings were held in the evenings because the busy legal practitioners on the Commission found it difficult to attend meetings during the court hours.

We were asked to report on the provisions of the Order in Council relating to the disqualification of persons for sitting or voting in Parliament. Two sections raised many difficulties, namely, the section disqualifying a person for holding a contract with the Crown and the section disqualifying persons who were serving or had served terms of imprisonment. A third difficulty arose by reason of the definition of ‘British subject’, which disqualified a person for sitting in Parliament if he was not a British subject.

‘British subject’ was defined in our Constitution to mean ‘a person who is a British subject according to the law for the time being of the United Kingdom, any person who has been naturalized under any enactment of any of His Majesty’s dominions and any person who is a citizen or subject of any of the Indian States as defined for the purposes of the Government of India Act, 1935″. Then came the British Nationality Act 1948, of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which created the status known as ‘Commonwealth citizen’, and gave it the same meaning as ‘British subject’.

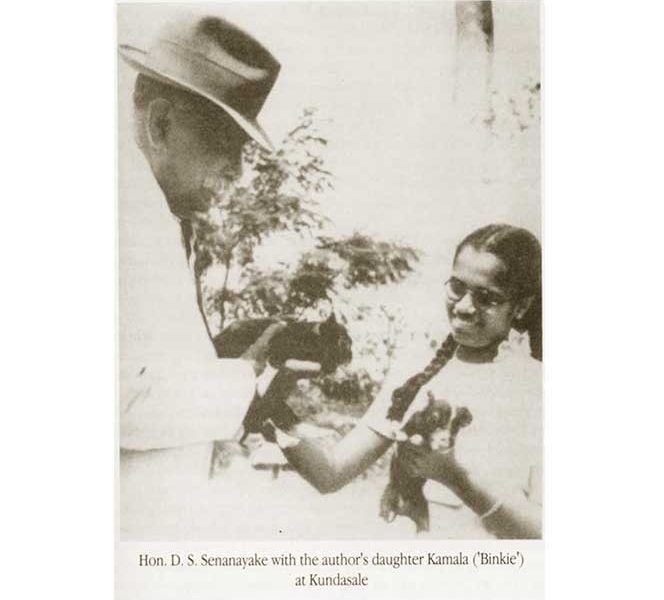

This complicated matters a bit as D.S. Senanayake was anxious to keep the Indian labourers on estates out of the franchise and out of membership of the House of Representatives. Sir Ivor agreed to write the Report on these three matters. I agreed to write the rest and asked him to send me his draft as I had to fit my language to suit his. The report, as finally drafted by Sir Ivor and myself, was agreed to by all the Commissioners; there was no dissent. It was published as Sessional paper No. I of 1949.

I was next directed by D.S. Senanayake to be Assistant Secretary to the Commonwealth Foreign Ministers’ meeting to be held in Colombo. This was the first time such an important conference was being held in Ceylon and we had no experience of how to run the secretariat. The Secretaries to the Conference were Sir Norman Brook, Secretary to the U. K. Cabinet, and Mr (later Sir) Kanthiah Vaithianathan, Permanent Secretary to the Ministry of Defence and External Affairs. The Assistants were, from Ceylon: B. Mahadeva, R. Coomaraswamy and I, and from the U. K., Lloyd of the Foreign office, Bavin and Sykes of the Cabinet Office and Davey of the Commonwealth Relations Office. The Chief Clerk was Pink of the U.K. Cabinet Office.

Pink arrived in Ceylon on an advance visit two months before the Conference was due to begin. The UK Government was obviously not going to take any risks by entrusting the running of the Conference to an inexperienced Ceylon secretariat. Pink introduced himself to me and said he had been sent to see to all the preliminary arrangements. The heavy equipment like steel filing cabinets, roneo machines, typewriters, dispatch cases etc. would all be brought from England.

Nine girls from the U. K. Cabinet office would be coming to run the office. We were asked to supply the paper, pencils, clips, pins and other little things normally used at a conference. Pink gave me a complete list of his requirements and wanted to see the Conference Room which was the Cabinet Room. He was satisfied. Apart from the delegations, there was room only for three officials from each delegation. He wanted to see where Sir Norman would work, where the Assistants would work, and where he and the girls would work, all with one eye on absolute security, The President of the Senate had placed the entire Senate Building, except the Chamber, at the disposal of the staff. Pink was thoroughly satisfied with the arrangements.

Before he left, I took him out to show him a bit of the country. He had been so busy during his short stay that he had no time to get out of Colombo. We drove to the Hanwella rest house along the Low Level Road and there had a couple of glasses of arrack which I carried in a flask. Pink took about three millimeters topped up with ginger beer, and said it was far too strong.

On the return, we took the High Level Road to my home for lunch. I had asked my wife to prepare a lunch of rice and ‘soft’ curries, without too much pepper and chilly. Pink enjoyed the lunch and the drive and remembered the arrack when he came a second time for the Conference.

It was my duty to get the Conference Room ready. I had the floors and tables highly polished. Staffs for the flags of the different nations represented at the Conference had to be specially made and erected. In view of the rather unusual frontage of the Senate building, these staffs had to be of different lengths as all the flags had to fly at the same height. This work was carried out by the Public Works Department. The table was ready the day previous to the Conference, with a tin of cigarettes for each delegation, a decanter of water, matches etc. The room looked like a mirror. I locked the door and took the key in my charge.

Officers of the Criminal Investigation Department then walked in and asked me for permission to inspect the room from the point of view of security. I said I had already had a look, locked the room and taken the key. They said it was their responsibility and not mine, and demanded the key, which I was forced to give. They were armed with stepladders, electric torches and I don’t know what else. I reminded them that the floor had been highly polished and begged of them not to spoil it by dragging their ladders along.

They were very careful with the floor. But they pulled every book out of the bookcases, they pulled the cushions out of the chairs, they climbed the ladders to examine the electric lights and the fans, they even went to inspect the lavatories in their fruitless search for hidden bombs. Having completed the search, the senior officer asked me to lock the room again and hand him the key. This, I refused to do, as I was responsible for the key.

He therefore posted an armed guard with a bayonet in front of the door with instructions that no one, not even myself, was to be allowed to enter the room until he came the next morning and dismissed the guard. I informed the officer that I had work to do inside the room the next morning and told him that the guard should be dismissed at 8 a.m.

On the next morning, the guard was still on duty when I arrived and had not been dismissed; nor was the officer present. I was prevented from opening the door. I asked him to go and call his officer, and he said he could not leave his post. I asked him what his orders were, and he said “Shoot if anyone tries to get in.” I was angry; but orders were orders, and the poor devil was only doing his duty. I also had a job to do. I told him that I would give him and his officer another half an hour, that I would then open the door, and that he could carry out his order.

Just as I went up the second time to open the door, the Inspector came panting and apologized to me. Strong words passed, and I had to tell him that if the guard did not dismiss himself automatically at 8 a.m. in future, I would have to go to the Prime Minister for his order. There was no further trouble.

The hours of duty during the ten days of the Conference were from about 7. 30 a.m. to about 3 a.m. the next morning. The staff of the Secretariat, including the nine girls (three of whom were extremely pretty) arrived by special plane and were housed at the Grand Oriental Hotel. The hours of work were such that they had no time to go to the hotel for meals and it was arranged that all meals should be served in the Senate Refreshment Room on Government hospitality.

One day, when I was sipping an arrack in the Refreshment Room (I had two bottles of double-distilled of my own), Sir Norman came in for a drink and inquired what I was having. I was having mine in a sherry glass. When I told him what my drink was, he said he had heard a lot about Ceylon arrack and expressed a desire to taste some. I called for my bottle but warned him that the drink was strong and advised him to dilute it. I was sipping mine neat and he said he would have it the same way and in the same sort of glass. He had several, after which I gave an order that whenever Sir Norman came for a meal, my bottle was to be placed on his table.

Sir Norman instructed each of his Assistants as regards his duties. We were each, in turn, to take a half hour of duty and present to him a draft, which he would consolidate and revise before circulation to the delegates. He worked hard at it till about 11 p.m. which was our normal dinner hour, his hair pulled down over his forehead and his bottle of gin on his table.

Vaithianathan was on the ceremonial side and had nothing to do with the minutes. Brook’s final draft was sent to the typing room to be attended to by the girls, who were in the charge of a lady supervisor from the U. K. Civil Service. Practice required that the minutes of a meeting should be on the breakfast plates of delegates the following morning. They were delivered to a responsible officer of the delegation under armed police guard.

Everything went well till about the third day. I was going down to dinner at about 11 p.m. when I found Pink coming out of his room for the same purpose. We walked along the corridor together. On the way, he said he was understaffed, that his girls were overworked, that in view of the secret nature of the work, typists from outside could not be employed, and inquired whether I had three typists in my office whose services I could spare. I had only three, and I released them all immediately for work in the typing room.

Now, for the actual Conference. As I said, elaborate security measures had been taken for the safety of the delegates and no person was admitted into the Senate building except on presentation of an identity card. Members of delegations were requested to make it a point to carry their cards and not to misunderstand the instruction. The police had been instructed to enforce the rule strictly.

Papers were circulated twice a day, at 8 a.m. and 10 p.m. in locked boxes, the keys of which were handed to the delegations as they arrived. Steel cabinets and iron safes were provided in the office of each delegation. S. K. D. Jayamane was in charge of Protocol. The Delegations were as follows:

Ceylon:

Rt Hon. D.S. Senanayake, Senator L. A. Rajapakse, Mr J. R. Jayewardene and Mr R. G. Senanayake.

United Kingdom

Rt Hon. Ernest Bevin, M. P., Rt Hon. P. J. Noel Baker, M. P., Rt Hon. Malcolm Macdonald and Sir Walter Hankinson

Canada

Mr Lester Pearson

Australia

Mr P. C. Spender, K. C., Mr H. R. Gollan, Mr J. E. Oldham and Mr C. W. Frost

New Zealand

Mr F. W. Doidge

South Afric

a Mr Paul Sauer and Mr D. D. Forsyth

India

Pandit Nehru, Mr V. K. Krishna Menon and Mr V. V. Giri

Pakistan

Mr Ghulam Mohamed, Mr H. I. Rahimtoola and Mr M. Ikramulla

Delegates arrived at the Cabinet office in cars displaying their National flags. Nehru, who arrived in the Governor-General’s car, preferred to return on foot amidst cheers from the crowd who were kept by the Police to the other side of the pavement. Ernest Bevin was a guest of the Prime Minister at ‘Temple Trees’. Other delegates were housed at different hotels.

One day, after my half hour of duty, I came out of the room to smoke but found I had no matches. Immediately, a gentleman seated in the lobby rose and said, “I can notice a man in distress, Sir, I am from Scotland Yard.” He was Bevin’s bodyguard. Nehru was a heavy smoker. He always left a meeting whistling one of Strauss’ Viennese waltzes.