Features

Courting Parthasarathy for JRJ, equation changes after Indira’s assassination

(Excerpted from volume ii of the Sarath Amunugama autobiography)

During one of my visits to Colombo I got a call to see the President at ‘Breamar’. Gamini Dissanayake had told him of my friendship with Parathasarathy and he wanted me to help him repair the damage done to their friendship due to the abuse heaped on GP when he came on a “peace mission” to Colombo.

JRJ had thrown his interlocutor into the ‘deep end’ by arranging a consultation for him with leading monks including Walpola Rahula. The monks had been particularly hard on GP as he was peddling the TULF line. GP was shocked because he had a vision of a peace loving and amiable ‘Sangho.’ that he was used to. Vietnamese Buddhist monks had supported him in his negotiations in Vietnam as Nehru’s envoy.

He had been shocked by this encounter with the monks and tended to think that JRJ had set them up. This was a time when JRJ was disoriented and perturbed by the spectre of 1956 which saw the decimation of the UNP. When I called over the following day at his residence the President was most cordial and inquired about my relations with GP.

He then pulled out a file in which he had gathered information from the time that GP had represented Madras State as a cricketer in the Gopalan Trophy, probably in the 1940s. GP had visited Colombo several times to play against the Ceylon eleven for the trophy. I remember that the news report from the Lake House archives had identified GP as a googly bowler; a good specialty for a future diplomat.

GP had later worked as a journalist in Madras till he moved to New Delhi to join Nehru’s entourage. He was so trusted by India Gandhi that she had appointed him to be the first Chancellor of the Jawaharlal Nehru University [JNU] then being built in the outskirts of Delhi. Since Parthasarathy had left Colombo a disappointed man, JRJ was keen to assure him that the Sri Lanka Government was ready to mend fences and start talking again.

This was a difficult undertaking because the July 1983 riots had severely embarrassed the Indian Government which was being pressurized by the Tamil Nadu politicians and the TULF to intervene. TULF leaders who fled after the riots were housed in Ashok Hotel in New Delhi and were able to get GP to promote their proposals.

Parathasarathy

I collected JRJ’s dossier and flew to New Delhi on my way to Paris GP was most cordial to me and invited me to have breakfast with him at his Lodhi Gardens home. Lodhi Gardens is located in a posh area of the Indian Capital. It housed many of the top officials of the Government. GP’s breakfasts were well known among Indian politicians and bureaucrats because many backroom discussions took place there.

It was a very English breakfast with a butler in atteendance. While breakfasting he assured me that he had no grudge with JRJ though his early goodwill when he accepted the assignment at Indira’s urging had been severely tested. He was agreeable to the idea that I telephone JRJ with that assurance of goodwill. He then pulled a rabbit out of his hat. He wanted me to ioin him on a visit to Ashok Hotel where the Indian Government had housed the leaders of the TULF after they were forced to flee the country following the July riots.

I had no hesitation in joining him as I knew some of these leaders, particularly Sampanthan with whom I had worked in Trincomalee when we demarcated the tourist zones for the Tourist Board. Perhaps GP, being a diplomat, wanted to show me the complex situation confronting Indian decision makers in view of the rapidly changing scenario in Sri Lanka.

Surprisingly the TULF leaders were keen to get back home. Though they were not short of creature comforts in the hotel they were not happy to be virtually incarcerated there without the chance of politicking in the North and East. In their absence the militants were making headway. Since their houses and other possessions in Colombo had been burnt or looted, they were in a state of shock.

Sampanthan told me that what he missed most was his library of books painstakingly collected over a lifetime. His library had been burnt down to the ground. I returned to Paris and telephoned JRJ who was happy that GP had responded that way. He wanted me to keep in touch with my Indian friends so that his position would not be misunderstood.

The Sri Lanka High Commision in New Delhi was not of much use and Hameed the Foreign Minister was asked not to interfere in the negotiations with India. Foreign Secretary Jayasinghe, though a good bureaucrat with strong connections with the Indian immigration officials, made no contribution in helping the President.

This was partly because the President was personally handling foreign policy issues. The lack of coordination in this sphere with a belligerent Lalith Athulathmudali playing a big role through his new Ministry, was beginning to extract its toll Lalith was quickly building up his popularity with the Sinhala voter by adopting a hardline and was being anxiously viewed be Premadasa, Gamini and Ronnie de Mel who could smell a rival when they saw one. The latter two were taking a more conciliatory approach which was welcomed by the Indian authorities.

Esmond’s Testimony

The periodic arrival of Esmond Wickremesinghe to Paris for International Programme for Development Communications (IPDC) meetings helped us to gather more information above the growing ethnic crisis in Sri Lanka. He told us that JRJ did not anticipate that the events of July would spiral out of control as Cyril Mathew had overstepped his brief Esmond said that he had breakfast with the President the day after the Kanatte incident. JRJ had collapsed at the breakfast table thinking that the Sinhala reaction would turn into a huge bloodbath which would be the end of his government.

He was fearful of a violent overthrow of his regime. That was why he prevaricated and did not address the nation immediately and put a stop to the violence. He hesitated and even in his broadcast he seemed to be lukewarm in condemning the Sinhala rioters and offering solace to the Tamils who were terrified and shocked. JRJ was perhaps right in feeling that this marked a watershed in his regime so early in his second term.

Soon after, all the energies of the Government were diverted to resettlement of refugees, funding them and attempting to recalibrate our economic and foreign policies to accommodate a solution to the ethnic problem. K.M. de Silva and Howard Wriggins in their biography of JRJ mark this as a turning point. “From this time to the end of his tenure of office as the Executive President at the end of December 1988. JR had to live with and deal with the consequences that flowed from the riots of 1983”.

As mentioned by writers like Rajiva Wijesinha, this crisis affected the Esmond Wickremesinghe family in different ways. Esmond’s brother Lakshman, who was the Bishop of Kurunegala, was devastated by the violence. He pleaded for reconciliation, but his cry was ignored. He died of a heart attack a few months later. Ranil Wickremesinghe on the other hand did not want to antagonize the Sinhala nationalist voters and tended to side with Mathew who had a strong base in the Kelaniya-Biyagama area.

Esmond while being disturbed by these events evaded the issue by dealing with the technical aspects of the problem on behalf of JRJ. Unlike his brother he was not disturbed by the moral dimension of the fratricidal violence. He felt that he could not abandon his friend at this critical juncture. Like Rajiva Wijesinha I did not see any remorse in Esmond regarding this collective moral failure. In his latest book Rajiva draws an unflattering picture of JRJ in relation to the ethnic and human rights issues.

Esmond briefed us of the Parathsarathy proposals which at that time was hotly opposed by many including the monks like Walpola Rahula and the Mahanayake of Asgiriya, Palipane Chandananda. The Parthasarathy proposals were for the setting up of Provincial Councils in a merged North and East. He was a proponent of devolution of powers within a sovereign state.

When we met the TULF in Ashok Hotel he told the Tamil leaders that he had held the Assamese student leaders incommunicado in Delhi till they agreed to his proposals. This may have put fear in the heads of the TULF leaders who may be forgiven for thinking that they too were being held in Delhi to receive the Assamese treatment. They wanted to get back to Sri Lanka as early as possible.

But as we saw earlier, GP was heavily biased towards the TULF position and its leaders need not have entertained any fears. They were safe with GP. It was only with his departure that a more flexible solution became feasible. His departure was a direct consequence of the death of Indira. Her demise had a direct bearing on JRJ and Sri Lanka’s fortunes.

As the TULF leaders lamented there were “orphaned by her death”. India entered a new phase Of her destiny with the death of Indira or ‘Goddess Durga’ as her numerous enemies called her. It marked a sea change in India’s policy towards Sri Lanka.

Death of Indira

The tragic death of her favourite younger son Sanjay in an air accident affected Indira deeply. He was her choice to succeed her to the `gadi’. But tragedy was to strike the Nehru family again and again. With the death of Sanjay, Indira began to turn to Hinds mystics – particularly to a handsome Sadhu, which association had the gossip prone Delhi on overdrive. She also increasingly became autocratic.

As PM she had to face the growing strength of the Sikhs who had been assiduously wooed and pacified by her father. The Sikh leaders were pampered by Nehru who admired their commitment to the Indian Congress during the Independence movement. The ‘green revolution’ had turned the Punjab into the `granary of India’, which was growing more prosperous by the day.

Also, the out migration of Sikhs to western countries had created pockets of political influence abroad supporting the call for Khalistan – an independent Sikh state. RAW with Indira’s backing was creating local leaders like Bhindranwale, to undercut the troublesome independence seeking Akhali leaders. Standing firm on the Punjab was of the greatest strategic importance for her. As Indira was successful in creating a Bangladesh, could not her enemies, particularly Pakistan, create a Khalistan as tit for tat? In a way the notion of a sovereign Khalistan and Kashmir put a brake on RAW scenarios of an independent Eelam. Eelam could trigger other frightful prospects like a bigger `rogue’ Tamil Nadu outside the Indian Union. Khalistan was a litmus test for the integrity of the Indian Union and Indira unleashed her total strength against the Sikh separatists, led by a RAW invented religious leader Bhindranwale [a la Prabhakaran] who had now turned on his masters.

Indira authorized operation ‘Blue Star’ which was an all-out attack on the extremists holed up in the famous Golden Temple of the Sikhs in Amritsar. It was a murderous, no holds barred attack. The offensive succeeded, the rebels were flushed out and killed, the rebellion was aborted and the majority of Sikhs looked on Indira as a monster who had defiled their holiest site.

The direct result of Operation Blue Star was the assassination of Indira by her Sikh bodyguards when she had left her home on foot to her office a few yards away for a TV interview with BBC. Delhi erupted in an orgy of communal rioting in which thousands of Sikhs were killed and their houses torched. As many studies have shown-including Stanley Tambiah’s ‘Levelling Crowds’ – this was rioting on a mega scale.

It was difficult for Indian diplomats to point their finger at Colombo riots, under these circumstances. The death of Indira meant the end of GP’s leadership of the Sri Lanka negotiations. He was replaced by Romesh Bandari, the Foreign Secretary and personal friend of the new PM. Under Rajiv, who reluctantly succeeded his mother, other players in addition to Bandari entered the scene. They were R Chidambaram, a Harvard trained lawyer from Madurai and N. Ram from the famous Kasturi family – the owners of `The Hindu’.

Ram was a journalist, a Cambridge graduate and a cricketer. In the wings was Venkateshwaran of the Foreign Office who was briefly Foreign Secretary. An admirer of Krishna Menon, Venkateshwaran was a hardliner on the Tamil issue and was sacked summarily by Rajiv Gandhi. The monopoly of Tamilians over Foreign policy was broken. This change of guard brought about a rethinking on India’s Sri Lanka policy.

It was an overall change of direction by Rajiv Gandhi who was moving towards an open economy and dismantling many socialist controls which had fast become dysfunctional during his mother’s ideologically rigid regime. Several of her socialist oriented officials, who were anyway superannuated by now, were shunted aside and a more technology oriented American educated coterie were assembled around the new Prime Minister.

The death of Indira was a blow to the hawks in her entourage who wanted a decisive push against JRJ and the Sri Lankan government. Indira had been looking for a political coup for her Congress party which for the first time since Independence was being challenged by the Janata Party led by former stalwarts of the Congress like Jayaprakash Narayan. She had tried to do something big in the South to bolster her strength and checkmate her political opponents. Her death was therefore a misfortune for the Tamil ‘Ultras’, as Rajiv did not have the same commitment towards them. The LTTE confirmed this set back by planning to assassinate him.

Features

Acid test emerges for US-EU ties

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen addressing the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland on Tuesday put forward the EU’s viewpoint on current questions in international politics with a clarity, coherence and eloquence that was noteworthy. Essentially, she aimed to leave no one in doubt that a ‘new form of European independence’ had emerged and that European solidarity was at a peak.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen addressing the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland on Tuesday put forward the EU’s viewpoint on current questions in international politics with a clarity, coherence and eloquence that was noteworthy. Essentially, she aimed to leave no one in doubt that a ‘new form of European independence’ had emerged and that European solidarity was at a peak.

These comments emerge against the backdrop of speculation in some international quarters that the Post-World War Two global political and economic order is unraveling. For example, if there was a general tacit presumption that US- Western European ties in particular were more or less rock-solid, that proposition apparently could no longer be taken for granted.

For instance, while US President Donald Trump is on record that he would bring Greenland under US administrative control even by using force against any opposition, if necessary, the EU Commission President was forthright that the EU stood for Greenland’s continued sovereignty and independence.

In fact at the time of writing, small military contingents from France, Germany, Sweden, Norway and the Netherlands are reportedly already in Greenland’s capital of Nook for what are described as limited reconnaissance operations. Such moves acquire added importance in view of a further comment by von der Leyen to the effect that the EU would be acting ‘in full solidarity with Greenland and Denmark’; the latter being the current governing entity of Greenland.

It is also of note that the EU Commission President went on to say that the ‘EU has an unwavering commitment to UK’s independence.’ The immediate backdrop to this observation was a UK decision to hand over administrative control over the strategically important Indian Ocean island of Diego Garcia to Mauritius in the face of opposition by the Trump administration. That is, European unity in the face of present controversial moves by the US with regard to Greenland and other matters of contention is an unshakable ‘given’.

It is probably the fact that some prominent EU members, who also hold membership of NATO, are firmly behind the EU in its current stand-offs with the US that is prompting the view that the Post-World War Two order is beginning to unravel. This is, however, a matter for the future. It will be in the interests of the contending quarters concerned and probably the world to ensure that the present tensions do not degenerate into an armed confrontation which would have implications for world peace.

However, it is quite some time since the Post-World War Two order began to face challenges. Observers need to take their minds back to the Balkan crisis and the subsequent US invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq in the immediate Post-Cold War years, for example, to trace the basic historic contours of how the challenges emerged. In the above developments the seeds of global ‘disorder’ were sown.

Such ‘disorder’ was further aggravated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine four years ago. Now it may seem that the world is reaping the proverbial whirlwind. It is relevant to also note that the EU Commission President was on record as pledging to extend material and financial support to Ukraine in its travails.

Currently, the international law and order situation is such that sections of the world cannot be faulted for seeing the Post World War Two international order as relentlessly unraveling, as it were. It will be in the interests of all concerned for negotiated solutions to be found to these global tangles. In fact von der Leyen has committed the EU to finding diplomatic solutions to the issues at hand, including the US-inspired tariff-related squabbles.

Given the apparent helplessness of the UN system, a pre-World War Two situation seems to be unfolding, with those states wielding the most armed might trying to mould international power relations in their favour. In the lead-up to the Second World War, the Hitlerian regime in Germany invaded unopposed one Eastern European country after another as the League of Nations stood idly by. World War Two was the result of the Allied Powers finally jerking themselves out of their complacency and taking on Germany and its allies in a full-blown world war.

However, unlike in the late thirties of the last century, the seeming number one aggressor, which is the US this time around, is not going unchallenged. The EU which has within its fold the foremost of Western democracies has done well to indicate to the US that its power games in Europe are not going unmonitored and unchecked. If the US’ designs to take control of Greenland and Denmark, for instance, are not defeated the world could very well be having on its hands, sooner rather than later, a pre-World War Two type situation.

Ironically, it is the ‘World’s Mightiest Democracy’ which is today allowing itself to be seen as the prime aggressor in the present round of global tensions. In the current confrontations, democratic opinion the world over is obliged to back the EU, since it has emerged as the principal opponent of the US, which is allowing itself to be seen as a fascist power.

Hopefully sane counsel would prevail among the chief antagonists in the present standoff growing, once again, out of uncontainable territorial ambitions. The EU is obliged to lead from the front in resolving the current crisis by diplomatic means since a region-wide armed conflict, for instance, could lead to unbearable ill-consequences for the world.

It does not follow that the UN has no role to play currently. Given the existing power realities within the UN Security Council, the UN cannot be faulted for coming to be seen as helpless in the face of the present tensions. However, it will need to continue with and build on its worldwide development activities since the global South in particular needs them very badly.

The UN needs to strive in the latter directions more than ever before since multi-billionaires are now in the seats of power in the principle state of the global North, the US. As the charity Oxfam has pointed out, such financially all-powerful persons and allied institutions are multiplying virtually incalculably. It follows from these realities that the poor of the world would suffer continuous neglect. The UN would need to redouble its efforts to help these needy sections before widespread poverty leads to hemispheric discontent.

Features

Brighten up your skin …

Hi! This week I’ve come up with tips to brighten up your skin.

Hi! This week I’ve come up with tips to brighten up your skin.

* Turmeric and Yoghurt Face Pack:

You will need 01 teaspoon of turmeric powder and 02 tablespoons of fresh yoghurt.

Mix the turmeric and yoghurt into a smooth paste and apply evenly on clean skin. Leave it for 15–20 minutes and then rinse with lukewarm water

Benefits:

Reduces pigmentation, brightens dull skin and fights acne-causing bacteria.

* Lemon and Honey Glow Pack:

Mix 01teaspoon lemon juice and 01 tablespoon honey and apply it gently to the face. Leave for 10–15 minutes and then wash off with cool water.

Benefits:

Lightens dark spots, improves skin tone and deeply moisturises. By the way, use only 01–02 times a week and avoid sun exposure after use.

* Aloe Vera Gel Treatment:

All you need is fresh aloe vera gel which you can extract from an aloe leaf. Apply a thin layer, before bedtime, leave it overnight, and then wash face in the morning.

Benefits:

Repairs damaged skin, lightens pigmentation and adds natural glow.

* Rice Flour and Milk Scrub:

You will need 01 tablespoon rice flour and 02 tablespoons fresh milk.

Mix the rice flour and milk into a thick paste and then massage gently in circular motions. Leave for 10 minutes and then rinse with water.

Benefits:

Removes dead skin cells, improves complexion, and smoothens skin.

* Tomato Pulp Mask:

Apply the tomato pulp directly, leave for 15 minutes, and then rinse with cool water

Benefits:

Controls excess oil, reduces tan, and brightens skin naturally.

Features

Shooting for the stars …

That’s precisely what 25-year-old Hansana Balasuriya has in mind – shooting for the stars – when she was selected to represent Sri Lanka on the international stage at Miss Intercontinental 2025, in Sahl Hasheesh, Egypt.

That’s precisely what 25-year-old Hansana Balasuriya has in mind – shooting for the stars – when she was selected to represent Sri Lanka on the international stage at Miss Intercontinental 2025, in Sahl Hasheesh, Egypt.

The grand finale is next Thursday, 29th January, and Hansana is all geared up to make her presence felt in a big way.

Her journey is a testament to her fearless spirit and multifaceted talents … yes, her life is a whirlwind of passion, purpose, and pageantry.

Raised in a family of water babies (Director of The Deep End and Glory Swim Shop), Hansana’s love affair with swimming began in childhood and then she branched out to master the “art of 8 limbs” as a Muay Thai fighter, nailed Karate and Kickboxing (3-time black belt holder), and even threw herself into athletics (literally!), especially throwing events, and netball, as well.

A proud Bishop’s College alumna, Hansana’s leadership skills also shone bright as Senior Choir Leader.

She earned a BA (Hons) in Business Administration from Esoft Metropolitan University, and then the world became her playground.

Before long, modelling and pageantry also came into her scene.

She says she took to part-time modelling, as a hobby, and that led to pageants, grabbing 2nd Runner-up titles at Miss Nature Queen and Miss World Sri Lanka 2025.

When she’s not ruling the stage, or pool, Hansana’s belting tunes with Soul Sounds, Sri Lanka’s largest female ensemble.

What’s more, her artistry extends to drawing, and she loves hitting the open road for long drives, she says.

This water warrior is also on a mission – as Founder of Wave of Safety,

Hansana happens to be the youngest Executive Committee Member of the Sri Lanka Aquatic Sports Union (SLASU) and, as founder of Wave of Safety, she’s spreading water safety awareness and saving lives.

Today is Hansana’s ninth day in Egypt and the itinerary for today, says National Director for Sri Lanka, Brian Kerkoven, is ‘Jeep Safari and Sunset at the Desert.’

And … the all-important day at Miss Intercontinental 2025 is next Thursday, 29th January.

Well, good luck to Hansana.

-

Editorial4 days ago

Editorial4 days agoIllusory rule of law

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoUNDP’s assessment confirms widespread economic fallout from Cyclone Ditwah

-

Editorial5 days ago

Editorial5 days agoCrime and cops

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoDaydreams on a winter’s day

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoThe Chakka Clash

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoSurprise move of both the Minister and myself from Agriculture to Education

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoExtended mind thesis:A Buddhist perspective

-

Features4 days ago

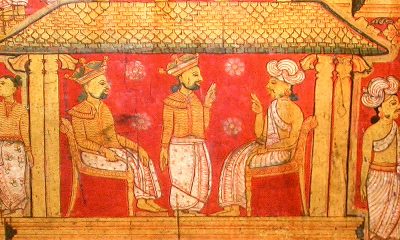

Features4 days agoThe Story of Furniture in Sri Lanka