Features

CONFESSIONS OF A GLOBAL GYPSY

MORE JUDO FIGHTING

By Dr. Chandana (Chandi) Jayawardena DPhil

President – Chandi J. Associates Inc. Consulting, Canada

Founder & Administrator – Global Hospitality Forum

chandij@sympatico.ca

… Continuing from last week’s column: ‘Judo Fighting in India’.

When I travelled to India as a member of the National Judo Team of Sri Lanka in 1982, I enjoyed different experiences of train travel and fun interactions in Madras, Sonipat, Ghaziabad and Delhi. After the main tournament in Ghaziabad, the 10-member first-ever national Judo team of Sri Lanka, assumed that the fighting portion of the trip was over. We were happily planning to spend a few days sightseeing in Delhi and its suburbs before returning home.

Brief Connections with Taj and Oberoi

In 1982, the largest hotel in Sri Lanka was managed by an Indian company – Oberoi. Taj hotels owned by India’s largest conglomerate – Tata Group, was building a five-star hotel in Colombo. After the Judo tournament in Ghaziabad, I planned to visit the famous Taj Palace Hotel and The Oberoi in New Delhi, as well as the Oberoi School of Hotel Management. Unfortunately, due to a last-minute change in the team’s travel plans, I did not get an opportunity to see these Iconic hotels managed by the two best-known Indian hotel companies.

In later years, I worked for both of these Indian hotel companies. From 1983 to 1985, I worked part-time at two Taj properties in London – Baily’s Hotel and Bombay Brasserie, which was ranked as the best Indian restaurant in the UK when it was opened in 1982. It paved the way for Indian and Bombay cuisine in London.

In 1989, I was recruited for the post of Food & Beverage Manager of the Hotel Babylon Oberoi in Iraq. In that position, I did my second trip to India. I managed 10 food and beverage outlets in the heart of Baghdad. My team of Indian managers and chefs also opened and operated an Indian restaurant. Most of my team of restaurant managers were graduates of the Oberoi School of Hotel Management. My experiences in India during the Judo trip in 1982, provided me with a good understanding of the Indian culture, which was beneficial to me when I worked for Taj and Oberoi.

Additional Fights and Fun in Hyderabad

Soon after the tournament in Ghaziabad, the Judo Association of Hyderabad invited us to a special Judo meet in their regional, army headquarters. When our team manager asked, “How many hours will it take for us to travel from Delhi to Hyderabad?”, the Indian judoka who was initiating the additional meet said, “It is very close… only 26 hours, by train!”. After a quick chat among our team, we decided to accept the invitation to go to Hyderabad to compete and explore.

We were disappointed to hear from an angry looking railway cashier at a train station in Delhi that the next train to Hyderabad was full. Our new Indian friend from Hyderabad told Upali, “No problem. Let me speak with this angry cashier and resolve this issue, amicably.” After a brief chat he had with the cashier, he returned with 11 train tickets with confirmed seat numbers. We were surprised and happy. “How did you do it? Upali asked. “Just a small bribe of 15 rupees, only!” our friend said. When we were getting into our compartment in the train, that cashier, now with a big smile said, “Enjoy your trip!”

The train ride was in many aspects similar to our previous marathon train ride of 52 hours from Madras to New Delhi. We passed some beautiful, lush mountainous locations, in between mostly hot and dry areas. Hyderabad is a unique city. It is the capital and the largest city of the Indian state of Telangana, as well as, the capital of Andhra Pradesh. It occupies a large area on the Deccan Plateau along the banks of the Musi River, in the upper part of South India.

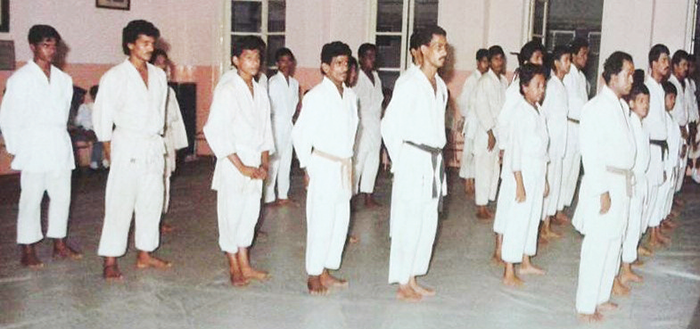

Much of Hyderabad is situated on hilly terrain around artificial lakes. Hyderabad is the sixth most populous city in India. In 1982 it had a population of over three million (in 2022 grown to over ten million). We were accommodated in an army camp in Hyderabad. They organized a good Judo meet. Due to injuries, our team manager, Upali Sahabandu decided to compete in the team category. He fought hard in a prolong bout, and our hosts were impressed. During the awards ceremony Upali was given a special award for his fighting spirit! We all lined up to receive our medals, which followed with a ceremony of tea service with excellent team from nearby estates.

We also loved the food in Hyderabad. From the time Hyderabad was conquered by the Mughals in the 1630s, Mughlai culinary traditions blended with the local traditions to create a unique Hyderabadi cuisine. This included Biriyani dishes highly popular in Sri Lanka. The day after the Judo meet, when we went on a sightseeing tour, we took part in another type of ceremony. It was a saree buying ceremony in the city. Some members of our team wanted to buy sarees for their mothers, sisters, and wives. While Upali and a few in the team showed some expertise about sarees, most of us were bored with shopping.

Tiruchirappalli, our last stop in India

After another long (over 21 hour) train ride we reached our last station – Tiruchirappalli (also called Trichy), which is an ancient city in India’s southern Tamil Nadu State. It was a relatively smaller city with a population of 600,000 in 1982 (doubled by the year 2022). It is known for the sacred Hindu sites, Sri Ranganathaswamy Temple with intricately carved gopurams (towering gateways) and the Jambukeswarar-Akilandeswari Temple, dedicated to the God Shiva.

In Trichy, we visited a few historic sites. The most impressive was Tiruchirappalli Rockfort, which towers over the city centre. It is a historic fortification and temple complex built on an ancient rock. The name ‘Rockfort’ comes from frequent, military fortification built there over the centuries by the Indian kings, and later by the British Colonisers. The oldest structure in the fort is an ancient cave temple.

After a quick flight from Trichy to Colombo, we arrived at the Katunayake International Airport to receive a hero’s welcome with garlands. As the first-ever tournament tour in another country by the national Judo team of Sri Lanka, those two weeks in 1982, that we spent in India, were truly memorable.

Members of the first National Judo Team, 40 years later

Recently, I checked where they are now and was saddened to discover that three members of Sri Lanka national Judo team in 1982 have passed away. I am happy to note that four of the team are still very much active in the sport of Judo. Four of the team also served the Sri Lanka Judo Association as the President.

= Upali Sahabandu (Team Manager) – 5th Dan Black Belt. Passed away during active service as a Deputy Inspector General of Sri Lanka Police.

= Kithsiri De Zoysa (Captain) – Now a 4th Dan Black Belt. President of the Jujitsu Federation Lanka. A leading referee for different martial art sports.

= Raja Fernando – Now a 6th Dan Red and White Belt, and the highest-ranking Sri Lankan Judoka. Instructs Judo in Sweden.

= Hemakumar Jinadasa – Now a 5th Dan Black Belt, and the highest-ranking Judoka in Sri Lanka. Instructs Judo at Colombo YMCA and many other Judo clubs.

= W. K. Godwin – Now a 4th Dan Black Belt. Retired an Assistant Superintendent of Police, but continues as the Head Judo Coach of the Sri Lanka Police Force.

= Gamini Nanayakkara – 5th Dan Black Belt. Passed away during active service as a Lieutenant Colonel of the Sri Lankan Army.

= Gamini Rupasinghe – Now a 3rd Dan Black Belt. Lives in Australia.

= K. Navarathnam – Now a 3rd Dan Black Belt.

= D. H. Ranjith – Now a 2nd Dan Black Belt.

= M. F. M. Izamudeen – Now a 2nd Dan Black Belt.

= T. B. Koswatte – 1st Dan Black Belt. Passed away.

= Chandana Jayawardena – Retired from Judo in 1983 as a 1st Kyu Brown Belt, to focus on his global career in hospitality.

More Success on the Judo Mat

When I returned to Sri Lanka, I focused on passing Judo grade tests. Usually, Judokas faced one promotion test at a time. In my case, as I had a long lapse of ten years since the last grade promotion test, I was allowed to face three grading tests on one day in 1983. Having represented Sri Lanka was an advantage. I was awarded the brown belt first Kyu. Based on the syllabus prepared by Kodokan in Japan, a first kyu Judoka should have mastered 45 different aspects such as hand throws, hip throws, foot throws, holds, locks and chokes. The most difficult part was to remember Japanese terms for all 45 items (covered in five grade promotion tests).

My aim after that was to face the grading test for first dan black belt, as soon as possible. Due to my moving to the UK in 1983, for graduate studies in international hotel management, I placed that goal on a back burner. Unfortunately, I failed to find time to face anymore Judo grading tests. In the late 1980, when I worked in Colombo for three years as the Director of Food & Beverage of a five-star Le Meridien hotel, I was able to find time only for an occasional practice session at the Colombo YMCA.

My Final Judo Fight in 1993

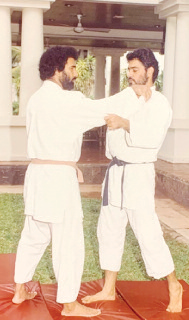

One of the songs I wrote in 1993 with an Indian Bangaram tune – ‘Fitness Fever’ became very popular. I was able to arrange twenty top western musicians of Sri Lanka to sing this song. It topped The Island pop charts for three weeks. Encouraged with the success of the song, I decided to direct a music video for it, which was filmed at the Ramada Renaissance hotel in Colombo. I included a Judo fighting scene in this video. I was one of the fighters for several takes of the Judo fighting scene. That was my last Judo fight.

I didn’t have any more Judo fights after that. However, I practised Karate for a short period of time in the mid-1990s in Jamaica. My aim then was to motivate my elder son, Marlon, who commenced Karate when he was ten years old. I was so proud of Marlon when he earned his Karate Black Belt in Sri Lanka when he was only 15 years old.

A Tribute to the Pioneers of Judo in Ceylon/Sri Lanka

To conclude my series of three articles on Judo, I wish to pay tribute to a few pioneers of Judo, a sport that was introduced to Ceylon around 1953. A well-known Ceylonese palaeontologist, zoologist, educator and artist, Paulus Edward Pieris Deraniyagala became the founding President of the Amateur Judo Association of Ceylon in 1953. He held that position for 19 years. Having studied in three of the best universities in the world (Cambridge, Oxford and Harvard) he became the Director of the National Museum of Ceylon. He was passionate about Judo.

Until the mid-1960s, there was no formal grading system for Judo in Ceylon. When I commenced Judo in 1970, in addition to P. E. P. Deraniyagala, there were three other leaders of the sport in Ceylon. They were, Lincoln Wijesinghe – the first Ceylonese to earn a Judo Black belt from Kodokan in Japan, Master Malcolm Atapattu – YMCA Judo Instructor and Master M. N. Tennakoon – YMBA Judo Instructor. Due to their commitment for Judo and hard work, Kodokan in Japan, chose Ceylon as a destination with a good potential for the sport.

These pioneers, with the help from young Judokas such as Peter Dharmaratne, Nihal Gooneratne and Asoka Jayawardana, developed strategies in promoting Judo in schools and carnivals. Japanese Judo teachers who were stationed in Sri Lanka – Sensei Yoda and Sensei Sato, helped by setting a high standard for Judo in Sri Lanka.Leadership of the Amateur Judo Association of Ceylon (re-named as the Sri Lanka Judo Association in 1974) during the first 50+ years was provided by nine Judokas with diverse backgrounds, including a zoologist, a chief justice, two senior police officers, a senior army officer and a hotelier.

I was fortunate to be included as a member of the national Judo team of Sri Lanka in 1982. At that time, there were only about 150 Judokas in the country belonging to just eight Judo clubs. Those clubs were, Colombo YMBA, Colombo YMCA, Dehiwela YMBA, Dehiwela YMCA Gampola Judo Club, Army, Navy and Police. In that context, the growth of Judo in Sri Lanka during the last four decades has been phenomenal.

Today there are around 15,000 Judokas (one third of this in the Army) in around 70 Judo clubs in Sri Lanka. Today, there are around 300 Kodokan black belts and another 70 locally graded, black belts in Sri Lanka. Growth by 100 times within 40 years, is indeed a great success story for any sport. I am proud of my former Judo colleagues, for their amazing commitment and their love for this sport. Well done!

Features

Trials-at-Bar in Sri Lanka: Use and abuse

It is reported that a Trial-at-Bar is being contemplated in respect of allegations against former President Ranil Wickremesinghe regarding misuse of state resources for a visit to a British university on his return from attending sessions of the United Nations in New York and an official visit to Cuba. If this is correct, it would make legal history in our country, because there has been no previous instance of the procedure of a Trial-at- Bar being invoked against a former Head of State.

In view of the constitutional importance of the issues involved, the attempt is opportune to consider the conceptual and statutory foundations of our law relating to Trials-at-Bar, the boundaries of its application in practice, and the nature of the responsibilities attributed to the principal functionaries with regard to the conduct of these proceedings.

I. The Statutory Framework

A Trial-at-Bar is an extraordinary procedure operating over and above proceedings in regular courts exercising criminal jurisdiction at first instance. Its form is that of three judges of the High Court, sitting usually without a jury, to try an indictable offence. The main provision is contained in Section 12 of the Judicature Act, No. 2 of 1978: “Notwithstanding anything to the contrary in this Act or any other written law, a Trial-at-Bar shall be held by the High Court in accordance with law for offences punishable under the Penal Code and other laws”.

The law of Sri Lanka makes provision for Trials-at-Bar in two different contexts.

(a) Mandatory

The trial of any person for the gravest offences against the State, constituted by Sections 114, 115, and 116 of the Penal Code, must in all circumstances be held before the High Court at Bar by three judges without a jury, despite any other law. This is the effect of Section 450 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, Act No. 15 of 1979.

The gist of offences to which this provision is applicable is conspiracy or preparation to overthrow, by unlawful means, the Government of Sri Lanka. This provision was applied in the case of 24 persons alleged to have attempted a coup d’état against the Government of Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike, a year after its election in July 1960 (R v. Liyanage).

(b) Discretionary

Outside this category, where recourse to a Trial-at-Bar is compulsory, there are other situations in which, as a matter of discretion, the Chief Justice may order use of this procedure. This course of action may be resorted to “in the interest of justice and based on the nature or circumstances of the offence”.

Trials-at-Bar, which may proceed either on indictment or on an information exhibited by the Attorney-General, are required to be held as speedily as possible, and generally in the manner of a High Court trial without a jury.

The power of appointment of High Court judges conducting a Trial-at-Bar is specifically vested in the Chief Justice. The Court, once appointed, has full authority regarding summoning, custody, and bail, subject to the restriction that bail may usually be granted only with the consent of the Attorney-General.

II. Appropriate Parameters

A useful point of departure, as a means of determining the proper limits of this judicial procedure, is to examine the character of offences which have led in our country throughout the post-Independence era to the constitution of Trials-at-Bar. A classification of the decided cases during this entire span of more than seven decades is attempted here for this purpose.

(1) Murder

Several Trials-at-Bar in Sri Lanka have been concerned with charges of murder, not per se, but invariably combined with circumstances which impart to the offence the added element of exceptional public importance, in terms of grave jeopardy to established institutions, public tranquillity, or seminal values underpinning governance.

The following are examples:

(a) the murder of a High Court judge engaged in the trial of five persons accused of capital offences pertaining to trafficking in drugs (Sarath Ambepitiya);

(b) the murder of a Member of Parliament in the midst of mob violence on a street, in the throes of widespread protests aimed at bringing down the incumbent government (Amarakeerthi Athukorala);

(c) the killing of two youth while in police custody (the Angulana case);

(d) the killing of villagers by Army personnel during a public demonstration (the Rathupaswala case);

(e) the disappearance of a social activist and human rights defender (Prageeth Ekneligoda).

(2) Offences involving State security and possible contravention of International law

* charges pertaining to firearms and ammunition and their use on the high seas (the Avant Garde case).

(3) Alleged gross dereliction of duty by senior government officials, including a former Secretary to the Ministry of Defence and a former Inspector-General of Police, leading to the death of a large number of persons by explosions in public places such as churches and hotels (Easter Sunday Bombing case).

(4) Grave corruption allegations in respect of procurement or other major misdemeanours

* two Trials-at-Bar were appointed to hear cases arising from the Central Bank bond scam in 2016, alleged to involve a former Minister of Finance, a former Governor of the Central Bank, his son-in-law and others (Central Bank bond case);

* charges against a previous Minister of Health, senior officials of the Ministry, and others in connection with the procurement of substandard immunoglobulin vials, leading to deaths and grievous bodily harm (Keheliya Rambukwella);

* charges filed by the Financial Crimes Investigation Division against the Chief of Staff of a former President and a former Chairman of the Sri Lanka Insurance Corporation for alleged large-scale misappropriation of public funds (Gamini Senerath, Priyadasa Kudabalage).

(5) Sedition involving communal overtones and potential disturbance of the public peace (S.J.V. Chelvanayakam and others).

(6) Allegations relating to extra-judicial executions

* the trial of a previous Army Commander for statements made by him regarding unlawful execution of surrendering LTTE cadres (Sarath Fonseka White Flag case).

(7) Criminal defamation in volatile contexts

In 1954, in the earliest of this series of cases, allegedly defamatory remarks were published by the defendant in a newspaper known as Trine. The gist of the allegations was that Sir Oliver Goonetilleke, who had just relinquished the position of Minister of Finance to accept appointment as Governor-General, had engaged in “swindles on an international scale” (R v. Thejawathie Gunawardena).

The heinous character of the offences alleged, and the scope of their potential ramifications in all these settings, are evident at a glance. The distinguishing feature is not merely the gravity of the offence, but imputation of a wider dimension to it, typically in the form of a serious affront to the public wellbeing.

In the Thejawathie Gunawardena case, for instance, where the propriety of recourse to a Trial-at-Bar was vigorously challenged, the Supreme Court held that there was no ground for complaint because of the predominant element of public mischief apparent from the circumstances. This was due to the inflammatory content of the statements published, which could foreseeably “disturb or endanger the government” by igniting public feeling. Gravity of the allegations, from this point of view, and their probable impact on public confidence in the integrity of basic institutions of governance, were the factors relied upon to take the case out of the regular category of defamation litigation and justify use of the Trial-at-Bar procedure.

This characteristic of a high threshold of public importance, accompanied by complexity and volatility of the surrounding circumstances, is the central thread which runs through the diverse situations in which Trials-at-Bar have been constituted in Sri Lanka.

III. The Roles of Pivotal Functionaries

The principal responsibility is that of the Chief Justice and the Attorney-General. The essential nexus between their statutory functions is a salient feature of the law.

(i) The Chief Justice

In Somaratna Rajapaksa v. Attorney-General, it was clearly recognised that the repository of power to constitute a Trial-at-Bar is the Chief Justice, but subject to the requirement that an indictment or information “furnished by the Attorney-General” operates as the material basis for exercise of the Chief Justice’s authority in this regard.

An explicit trajectory is established, linking the initiative by the Attorney-General with the Chief Justice’s decision.

(ii) The Attorney-General

Action by the Attorney-General is located within the overall ambit of prosecutorial discretion vested in him in respect of a wide range of matters, including assessment of the sufficiency and probative value of evidence to warrant institution of criminal proceedings, the decision to indict, and withdrawal of a prosecution by means of the entering of a nolle prosequi. The recommendation in respect of a Trial-at-Bar falls into place within the field of this broad authority.

The crucial attribute of the Attorney-General’s functions in this area is that he acts in a quasi-judicial capacity. A basic anomaly in the role of the Attorney-General in our constitutional system is that he combines, in his office, a variety of functions and responsibilities which entail some degree of conflict with one another. Despite this lack of institutional coherence and consistency, what is beyond doubt in the present condition of the law is that, throughout the whole gamut of prosecutorial decision making, the Attorney-General is required to eschew all political and other extraneous considerations and to arrive at his decisions in a spirit of total objectivity.

This is one of the cornerstones of our system of criminal justice. Although there is a statutory choice or discretion built into the Attorney-General’s responsibility, H.N.G. Fernando C.J. has aptly commented: “Our law has conferred on the Attorney-General powers which have been commonly described as quasi-judicial and traditionally formed an integral part of the system of criminal procedure” (Attorney-General v. Don Sirisena). In similar vein, the Supreme Court, in Victor Ivan v. Sarath N. Silva, Attorney-General, observed: “The Attorney-General’s power is a discretionary power similar to other powers vested in public functionaries, held in trust for the public, and not absolute or unfettered”.

While the purview of prosecutorial discretion residing in the Attorney-General, by virtue of enacted law as well as inveterate tradition, is strikingly extensive, it is not an untrammeled power: it is not beyond the reach of the courts. In a trilogy of progressive decisions by the Court of Appeal, Sobitha Rajakaruna J., (prior to his elevation to the Supreme Court), asserted the principle that the Attorney-General’s decisions, in appropriate circumstances, are amenable to judicial review: Sandresh Ravi Karunanayake v. Attorney -General (CA/Writ/ 441/2021), Duminda Lanka Liyanage v. Attorney-General (CA/Writ/323/2022), Nadun Chinthaka Wickremaratne v. Attorney-General (CA/Writ/523/2024).

In Attorney-General v. Karunanayake, Samayawardhana J ( with the concurrence of Thurairaja and Janak de Silva JJ.) declared: “Politically motivated indictments following regime change pose a serious threat to the rule of law and public confidence in the office of the Attorney-General and the entire justice system. Judicial oversight plays a vital role in ensuring that prosecutorial discretion is exercised independently, fairly, and in compliance with the law”.

The Supreme Court of our country has shown no inhibition in directly addressing the question whether the Attorney-General has properly exercised his discretion in laying the information which served as the basis of a Trial-at-Bar.

In Thejawathie Gunawardena’s case, in proceedings before the Supreme Court, it was strenuously contended on the defendant’s behalf that the Attorney-General had acted ultra vires for a collateral or improper purpose. The submission was that the person allegedly defamed was no longer holding public office, and invocation of the extraordinary procedure associated with a Trial-at-Bar was, therefore, unjustifiable. The Supreme Court, sitting in appeal, having considered the issue in depth, rejected the submission on the ground that his tenure had been very recent, and that the proximity of his connection with the incumbent government gave rise to the likelihood of intensifying public feeling because of the volatility and range of the allegations made against him.

These trends of judicial opinion have the effect that the principle of justiciability of the Attorney-General’s initiative in this regard is firmly embedded in our law.

IV. Conclusion

Trials-at-Bar serve a salutary purpose, but within stringently circumscribed limits. The decided cases in our country, spanning more than 75 years, indicate with exemplary clarity the confines within which this extraordinary procedure has legitimacy. The essential consideration is that there should not be room for the slightest doubt that immaterial factors may have come into play in the exercise of discretion.

This far transcends the entitlement of individuals to due process and impinges upon the health and vitality of procedures central to the administration of justice. My teacher, Professor Sir William Wade, pre-eminent among exponents of administrative law in our time, who had the distinction of holding Chairs of Law successively in the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, told me that if he were asked to identify succinctly, in one sentence, the substance of the common law tradition, he would have no hesitation in replying that it consisted of robust hostility to unbridled discretion in public functionaries. Even the appearance of neglect of this rudimentary principle places in jeopardy the fulfilment of public aspirations about the quality of criminal justice.

By Professor G. L. Peiris ✍️

D. Phil. (Oxford), Ph. D. (Sri Lanka);

Former Minister of Justice, Constitutional Affairs and National Integration;

Quondam Visiting Fellow of the Universities of Oxford, Cambridge and London;

Former Vice-Chancellor and Emeritus Professor of Law of the University of Colombo

Features

Extended mind thesis:A Buddhist perspective

After listening to Prof. Charitha Herath deliver his lecture at the World Philosophy Day Conference at the University of Peradeniya and then reading his excellent article, “Buddhist insights into the extended mind thesis – some observations” published in The Island (14.01.2026) I was prompted to write this brief note to comment on the Buddhist concepts he says need to be delved into in this connection. The concepts he mentioned are prapañca, viññāṇasota and ālayaviññāṇa.

Let us look at the Extended Mind Thesis in brief. “The extended mind thesis claims that the cognitive processes that make up the human mind can reach beyond the boundaries of an individual to include as proper parts aspects of the individual’s physical and sociocultural environment” … “Such claims go far beyond the important, but less challenging, assertion that human cognition leans heavily on various forms of external scaffolding and support. Instead, they paint the mind itself (or better, the physical machinery that realises some of our cognitive processes and mental states) as, under humanly attainable conditions, extending beyond the bounds of skin and skull.

Extended cognition in its most general form occurs when internal and external resources become fluently tuned and deeply integrated in such a way as to enable a cognitive agent to solve problems and accomplish their projects, goals, and interests. Consider, for instance, how technological resources such as pens, paper, and personal computers are now so deeply integrated into our everyday lives that we couldn’t accomplish many of our cognitive goals and purposes without them (Kiverstein J, Farina M, Clark A, 2013).

It may be seen from the above that the Extended Mind Thesis is mainly concerned with human cognition. It seems that the tools that humans use to help them in the cognitive process are actually components of the extended mind. This is mentioned in Prof. Herath’s article as well. Though Buddhist theory of cognition does not imply such a relationship that involves the implements utilised in the process of acquiring knowledge, it proposes an inextricable relationship between the cogniser and the cognised. For instance, the eye-consciousness does not arise unless the object of cognition is present.

Reality of the world according to Buddhism is based on the relationship between the cogniser and the cognised. This theory is supported by the way in which Buddhism analyses the complex formed by the human personality and the world, which it does in three systems, expounding the bond between the two. First is the five aggregate analysis, second is the 12 bases (ayatana), and the third is the eighteen elements (dhatu). Whether this kind of entanglement is possible without some means of extending the mind is an interesting question.

According to Buddhism, the mind is not a substance but rather a function that depends on it. There are three terms that are used to refer to mind and possibly these may indicate different functions though they are very often used as near-synonyms. The terms are mano, citta and viññāṇa. The term mano is used to refer to the aspect of mind that functions as one of the six sense-faculties. Mano is responsible for feelings and it also coordinates the functions of the other sense-faculties. Citta generally means consciousness or combinations of consciousness and the other mental-factors, vedanā, saññā, sankāra as seen in the Abhidhamma analyses.

The term Viññāṇa means basic awareness of oneself and it is also used in relation to rebirth or rebecoming. It has a special responsibility in being the condition for the arising of nama-rupa, and reciprocally nama-rupa is the condition for consciousness in the paticcasamuppada formula. Further, the term “consciousness-element” is also used together with five other items; earth-element, water-element, fire-element, air-element and space-element which seem to refer to the most basic factors of the world of experience, indicating its ability to connect with the empirical world (Karunadasa, 2015). In these functions, consciousness may assume some relevance in the Extended Mind Thesis.

Further if we examine the role of consciousness in rebirth we find that a process called the patisandhi-viññāṇa has the ability to transmit an element, perhaps some karmic-force, from the previous birth to the subsequent birth. In these functions the enabling mechanism probably is the viññāṇasota, the stream of consciousness that Prof. Herath mentions, and which apparently has the ability to flow even out of the head and establish links with the external world.

It may be relevant at this juncture to look at the contribution made by Vasubandhu, the 4th Century Indian Buddhist philosopher. Vasubandhu’s interpretation of saṃskārapratyayaṃ vijñānam (consciousness conditioned by volitional actions) treats the stream of consciousness as the mechanism of continuity between lives. He emphasises that this stream continues without a permanent entity migrating from one life to the next. The “stream” manifests as the subject (ego) and object (external world), which are both considered projections of this underlying consciousness, rather than independently existing entities. Vasubandhu also had proposed a kshnavada (theory of moments) to explain the stream of consciousness as consisting of arising and disappearing of consciousness maintaining continuity. These propositions may lend support to the Extended Mind Thesis.

Prof. Herath has mentioned the term prapañca (Pali – papañca) which generally means concepts. In the context of the extended mind thesis it needs to be examined in relation to the Buddhist theory of perception, because the former mainly pertains to cognition. As mentioned by Prof Herath, Ven. Nanananda in his book “Concept and Reality” has discussed this subject emphasising the fact that in Buddhist literature the term papañca is used mainly in the context of sense-perception. He says that “Madhupindika Sutta” (Majjima Nikaya) points to the fact that papañca is essentially connected with the process of sense perception. According to the Buddhist theory of perception the final outcome or the final stage of the process is the formation of papañca. Following the formation of concept there is proliferation of the concept depending on the past experience the individual may have in relation to what is perceived.

This process of perception, as given inthe Madhupindika Sutta, leading to conceptual proliferation is at the beginning impersonal and in the later stages it becomes personal with the involvement of the human personality with its self-ego and craving and finally leading to total bondage. And this bondage is between the human mind and the external world. Whether this entails an extended mind needs to be researched as suggested by Prof. Herath.

The third concept that Prof. Herath referred to in his lecture is the Yogacara idea of ālayaviññāṇa. Yogacara in its analysis of consciousness has added two more types of consciousnesses to the six based on the six senses, which is the classification mentioned in Early Buddhism and the two additional ones are kleshaviññāṇa and ālayaviññāṇa. The latter is called the storehouse-consciousness as it carries the seeds of karma. It is also called the approximating consciousness as it approximates at two levels; in this birth by collection of defilements and in the next birth by carrying them across in rebirth. The latter function may be relevant to the Extended Mind Thesis as it has the ability of projection beyond the body of the present birth and transmit to the body of the next birth.

If one is interested in researching into the concept of ālayaviññāṇa one must be aware that the three masters of Yogacara, i.e. Maithreyanata, Asanga and Vasubhandhu did not agree with each other on the nature of ālayaviññāṇa. While Maithreyanata was loyal to the early Yogacara idea that appeared in Sandhinirmocana Suthra, Asanga modified it to suit his thesis of idealism. Vasubandhu, however, adhered to the views of Early Buddhism and according to Kalupahana (1992) what he in his Trimsathika describes is the transformation of the consciousness and not the eight consciousnesses in the order in which they appear in Yogākāra texts. Here one is tempted to suggest that Asang’s idealism which propounds that the external world is a creation of the mind may lend support to the extended mind thesis. Idealism in Yogacara Buddhism may be another subject that needs to be researched in the context of the extended mind thesis.

Turning to recent research there is theoretical and speculative support from quantum theory for the idea of extended consciousness, but it remains a controversial area of research within physics, neuroscience, and philosophy. Several frameworks suggest that consciousness is not confined to the brain but is a fundamental, non-local phenomenon rooted in quantum processes that may connect minds to each other or the universe at large. (Wagh, M. (2024). “Your Consciousness Can Connect with the Whole Universe, Groundbreaking New Research Suggests”. Popular Mechanics. Retrieved from https://www.popularmechanics.com/scienc)

Finally, while it may not be clear whether the Extended Mind Thesis, as proposed by A. Clark and others (2013), has anything to do with consciousness it may be worthwhile to research into this matter from a Buddhist perspective, which will have to strongly bring into contention the factor of consciousness, which perhaps may have the potential to develop into an Extended Consciousness Thesis.

by Prof. N. A. de S. Amaratunga ✍️

PhD, DSc, DLitt

Features

Why siloed thinking is undermining national problem-solving

The world today is marked by paradox. Never before has humanity possessed such extraordinary scientific knowledge, technological capability, and research capacity. Yet never before have we faced such a dense convergence of crises—climate change, biodiversity loss, pandemics, food insecurity, widening inequality, disaster vulnerability, and social fragmentation. These challenges are not isolated events; they are deeply interconnected, mutually reinforcing, and embedded within complex social, ecological, economic, and technological systems. Addressing them effectively demands more than incremental improvements or isolated expertise. It requires a fundamental shift in how we think, research, and act.

At the heart of this shift lies transdisciplinarity: an approach that moves beyond siloed disciplines and engages society itself in the co-creation of knowledge and solutions. As Albert Einstein famously observed, “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.” The persistence of today’s global challenges suggests that our prevailing modes of problem-solving—largely mono-disciplinary and compartmentalised—are no longer adequate.

The limits of siloed knowledge

Over the past few decades, global investment in research and development has grown dramatically. Global R&D expenditure exceeded USD 3 trillion in 2022, and the worldwide scientific workforce has expanded to more than 8.8 million researchers, producing millions of academic papers annually across tens of thousands of journals. Indeed, the number of scientists has grown several times faster than the global population itself. This extraordinary expansion reflects humanity’s faith in science as a driver of progress—but it also sharpens an uncomfortable question about returns on this investment. Millions of scientists across the world produce an ever-expanding body of academic literature, filling tens of thousands of specialised journals. This disciplinary research has undoubtedly driven remarkable advances in medicine, engineering, agriculture, and information technology. The positive contributions of science to human civilisation are beyond dispute. Yet its effectiveness in addressing complex, real-world challenges has often fallen short of expectations, with impacts appearing disproportionate to the vast resources committed. Yet the translation of this vast knowledge base into tangible, scalable solutions to real-world problems remains limited.

The reason lies not in a lack of intelligence or effort, but in the way knowledge is organised. Disciplines are, after all, social constructs, each shaped by its own conceptual, theoretical, philosophical, and methodological traditions. While these traditions enable depth and rigour, they also encourage intellectual compartmentalisation when treated as ends in themselves. Modern academia is structured around disciplines—biology, economics, engineering, sociology, medicine—each with its own language, methods, reward systems, and institutional boundaries. These disciplines are powerful tools for deep analysis, but they also act as intellectual blinders. By focusing narrowly on parts of a problem, they often miss the broader system in which that problem is embedded.

Climate change, for example, is not merely an environmental issue. It is simultaneously an economic, social, political, technological, and ethical challenge. Public health crises are shaped as much by social behaviour, governance, and inequality as by pathogens and medical interventions. Poverty is not simply a matter of income, but of education, health, gender relations, environmental degradation, and political inclusion. Approaching such issues from a single disciplinary lens inevitably leads to partial diagnoses and fragmented solutions.

The systems thinker Donella Meadows captured this dilemma succinctly when she noted, “The problems are not in the world; they are in our models of the world.” When our models are fragmented, our solutions will be fragmented as well.

Wicked problems in a hyper-connected world

Many of today’s challenges fall into what scholars describe as “wicked problems”—issues that are complex, non-linear, and resistant to definitive solutions. They have multiple causes, involve many stakeholders with competing values, and evolve over time. Actions taken to address one aspect of the problem often generate unintended consequences elsewhere.

In a hyper-connected world, these dynamics are amplified. A disruption in one part of the global system—whether a pandemic, a financial shock, or a geopolitical conflict—can cascade rapidly across borders, affecting food systems, energy markets, public health, and social stability. Recent crises have starkly demonstrated how local vulnerabilities are intertwined with global forces.

Despite decades of research aimed at tackling such problems, progress remains uneven and, in many cases, distressingly slow. In some instances, well-intentioned scientific interventions have even generated new problems or unintended consequences. The Green Revolution of the 1960s, for example, dramatically increased cereal yields and reduced hunger in many developing countries, but its heavy dependence on agrochemicals has since contributed to soil degradation, water pollution, and public health concerns. Similarly, plastics—once hailed as miracle materials for their affordability and versatility—have become a pervasive environmental menace, illustrating how narrowly framed solutions can create long-term systemic risks. This gap between knowledge production and societal impact raises a critical question: are we organising our research and institutions in ways that are fit for purpose in an interconnected world?

What is transdisciplinarity?

Transdisciplinarity offers a compelling response to this question. Unlike multidisciplinary approaches, which place disciplines side by side, or interdisciplinary approaches, which integrate methods across disciplines, transdisciplinarity goes a step further. It transcends academic boundaries altogether by bringing together researchers, policymakers, practitioners, industry actors, and communities to jointly define problems and co-create solutions.

At its core, transdisciplinarity is problem-driven rather than discipline-driven. It starts with real-world challenges and asks: what knowledge, perspectives, and forms of expertise are needed to address this issue in a meaningful way? Scientific knowledge remains essential, but it is complemented by experiential, local, and indigenous knowledge—forms of understanding that are often overlooked in conventional research but are crucial for context-sensitive and socially robust solutions.

As C. P. Snow warned in his influential reflections on “The Two Cultures,” divisions within knowledge systems can themselves become barriers to progress. Transdisciplinarity seeks to bridge not only disciplines, but also the persistent gap between knowledge and action.

Learning from nature and society

Nature itself provides a powerful metaphor for transdisciplinary thinking. Ecosystems do not operate in compartments. Soil, water, plants, animals, and climate interact continuously in dynamic, adaptive systems. When one element is disturbed, the effects ripple through the whole. Human societies are no different. Economic systems shape social relations; social norms influence environmental outcomes; technological choices affect governance and equity.

Yet our institutions often behave as if these connections do not exist. Universities are organised into departments with separate budgets and promotion criteria. Research funding is allocated along disciplinary lines. Success is measured through narrow metrics such as journal impact factors and citation counts, rather than societal relevance or long-term impact.

This mismatch between the complexity of real-world problems and the fragmentation of our knowledge systems lies at the heart of many policy failures. While societal challenges have grown exponentially in scale and interdependence, organisational structures and problem-solving approaches have not evolved at the same pace. Attempting to address borderless global issues using rigid, compartmentalised, and outdated frameworks is therefore increasingly counterproductive. As former UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon aptly stated, “We cannot address today’s problems with yesterday’s institutions and mindsets.”

Transdisciplinarity and sustainable development

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) offer a vivid illustration of why transdisciplinary approaches are essential. The 17 goals—ranging from poverty eradication and health to climate action and biodiversity—are explicitly interconnected. Progress on one goal often depends on progress in others. Climate action affects food security, health, and livelihoods. Education influences gender equality, economic growth, and environmental stewardship.

Achieving the SDGs therefore requires more than sector-by-sector interventions. It demands integrated, cross-sectoral responses that align research, policy, and practice. Transdisciplinarity provides a framework for such integration by fostering collaboration across disciplines and sectors, and by grounding global goals in local realities.

For countries like Sri Lanka, with complex socio-ecological systems and rich cultural diversity, this approach is particularly relevant. In Sri Lanka, more than 6,000 individuals are engaged in research and development, with over 60 per cent based in universities and other higher education institutions. This places a particular responsibility on academic and institutional leaders to create environments that encourage collaboration across disciplines and with society. Policies, assessment schemes, funding mechanisms, and incentive structures within universities can either reinforce silos or actively nurture a transdisciplinary culture. Sustainable development challenges here are shaped by local contexts—coastal vulnerability, agricultural livelihoods, urbanisation patterns, and social inequalities—while also being influenced by global forces. Transdisciplinary engagement can help bridge this global–local divide, ensuring that policies and innovations are both scientifically sound and socially meaningful.

Why transdisciplinarity is hard?

Despite its promise, transdisciplinarity is not easy to practice or institutionalise. Deeply entrenched disciplinary identities often shape how researchers see themselves and their work. Many academics are trained to excel within narrow fields, and career advancement systems tend to reward disciplinary publications over collaborative, problem-oriented research.

Institutional structures can further reinforce these silos. Departments operate with separate budgets and governance arrangements, making cross-boundary collaboration administratively cumbersome. Funding mechanisms often lack categories for transdisciplinary projects, leaving such initiatives struggling to find support. Time pressures also matter: genuine engagement with communities and stakeholders requires sustained interaction, yet academic workloads rarely recognise this effort.

There are also cultural and ethical challenges. Different disciplines speak different “languages” and operate with distinct assumptions about what counts as valid knowledge. Power imbalances can emerge, with certain forms of expertise dominating others, including the voices of non-academic partners. Without careful attention to trust, equity, and mutual respect, collaboration can become superficial rather than transformative.

The way forward: from aspiration to practice

If transdisciplinarity is to move from rhetoric to reality, deliberate institutional change is required. Sri Lanka, in particular, would benefit from articulating a clear national vision that positions transdisciplinary research as a core mechanism for addressing challenges such as climate resilience, public health, disaster risk, and sustainable development. National research agencies and universities can play a catalytic role by creating dedicated funding streams, establishing transdisciplinary centres, and embedding systems thinking and stakeholder engagement within curricula and research agendas. First, awareness must be built. Universities, research institutes, and funding agencies need to invest in dialogue, training, and pilot projects that demonstrate the value of transdisciplinary approaches in addressing pressing societal challenges.

Second, leadership matters. Institutional leaders play a critical role in signalling that transdisciplinary engagement is not peripheral, but central to the mission of knowledge institutions. This can be done by embedding such approaches in strategic plans, allocating seed funding for collaborative initiatives, and recognising societal impact in promotion and evaluation systems.

Third, structures must evolve. Flexible research centres, shared infrastructure, and streamlined administrative processes can lower the barriers to collaboration. Education also has a role to play. Introducing systems thinking and problem-based learning early in undergraduate and postgraduate programmes can help cultivate a new generation of researchers comfortable working across boundaries.

Finally, ethics and inclusivity must be at the forefront. Transdisciplinarity is not merely a technical methodology; it is an ethical commitment to valuing diverse forms of knowledge and engaging communities as partners rather than passive beneficiaries. In doing so, it strengthens the legitimacy, relevance, and sustainability of solutions.

A collective learning challenge

Peter Senge once observed, “The only sustainable competitive advantage is an organization’s ability to learn faster than the competition.” This insight applies not only to organisations, but to societies as a whole. Our collective ability to learn, unlearn, and relearn—across disciplines and with society—will determine how effectively we navigate the challenges of our time.

The shift from siloed disciplines to transdisciplinary engagement is therefore not a luxury or an academic trend. It is a strategic necessity. In a world of complex, interconnected problems, fragmented knowledge will no longer suffice. What is needed is a new culture of collaboration—one that sees connections rather than compartments, embraces uncertainty, and places societal well-being at the centre of scientific endeavour.

Only by breaking down the walls between disciplines, institutions, and communities can we hope to transform knowledge into action, and action into lasting, equitable change.

A final word to Sri Lankan decision-makers

For Sri Lanka, the message is clear and urgent. Policymakers, university leaders, funding agencies, and development institutions must recognise that many of the country’s most pressing challenges—climate vulnerability, public health risks, food and water security, disaster resilience, and social inequality—cannot be solved within institutional silos. Creating space for transdisciplinary engagement is not a marginal reform; it is a strategic investment in national resilience. By aligning policies, incentives, and funding mechanisms to encourage collaboration across disciplines and with society, Sri Lanka can unlock the full value of its scientific and intellectual capital. The choice before us is stark: continue to manage complexity with fragmented tools, or deliberately build institutions capable of learning, integrating, and responding as a system. The future will favour the latter.

by Emeritus Professor Ranjith Senaratne ✍️

Former Vice-Chancellor, University of Ruhuna,

Former General President, Sri Lanka Association for the Advancement of Science

Former Chairman, National Science Foundation

-

Editorial2 days ago

Editorial2 days agoIllusory rule of law

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoUNDP’s assessment confirms widespread economic fallout from Cyclone Ditwah

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoKoaloo.Fi and Stredge forge strategic partnership to offer businesses sustainable supply chain solutions

-

Editorial3 days ago

Editorial3 days agoCrime and cops

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoDaydreams on a winter’s day

-

Editorial4 days ago

Editorial4 days agoThe Chakka Clash

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoSurprise move of both the Minister and myself from Agriculture to Education

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoThe Story of Furniture in Sri Lanka