Features

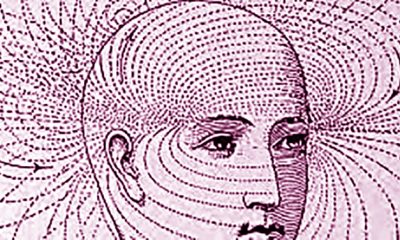

Challenging Times and Intellectual Pleasures: My Talk with Slavoj Žižek

by Nilantha Ilangamuwa

We sat down last Sunday evening around 5:30 in Ljubljana time, which was 8:30 in the evening here in Colombo. The purpose was not to delve into deep philosophical realms but rather to listen to Slavoj Žižek’s thoughts on a few prevailing social issues. It had been a longstanding dream of mine to convey his ideas to the general public, which is tired of jargon and seeks great ideas in simple language.

I first started communicating with Slavoj Žižek, the intellectual superstar known for his unstoppable yet profound talks in any public gathering. I owe this opportunity to David J. Gunkel of Northern Illinois University, with whom I had my very first discussion about this eminent philosopher approximately seven years ago. This Slovenian philosopher, armed with a humorous sense, expertly deconstructs the most serious challenges and profound ideologies, and he needs no introduction.

However, meeting Slavoj was challenging as he is currently facing health issues, including panic attacks. Being aware of this made me cautious not to tire him during our conversation. Nevertheless, as the night was still young, he passionately talked, and most of the time, I found it hard to interrupt him. However, as he jokingly suggested, I might have to use “Stalinist freedom” to condense the insights from our hour-long discussion. Slavoj displayed patience and skillfully identified points where we had to pause due to technical issues.

Stopping Slavoj when he is engrossed in conversation is quite inconvenient, and as a moderator, one might even forget their role. I shared with him that after years of communicating via email, it was my first time being in a live discussion with him, just the two of us. I jokingly remarked, “Slavoj, you are the most dangerous philosopher in the West. Oh God, you don’t look dangerous,” especially after hearing his brief observation on Sri Lanka during a time when its economic and political crisis dominated world headlines.

To this, Slavoj responded, “The branding of me as dangerous is a critique against my ideas. People who call me dangerous may also label me as despicable. I believe that such descriptions, whether politically dangerous, Stalinist, fascist, or merely as a joker, are used to undermine the seriousness of my work. Despite my jokes and provocations, I genuinely enjoy writing them. I’ll let you in on a secret: recently, New Statesman published three of my film reviews on Indiana Jones, Barbie, and Oppenheimer. Interestingly, I hadn’t seen any of these movies when I wrote the reviews. Instead, I read many reviews on them and then wrote my own. However, upon watching the films later, I realized that my initial assessments were accurate.”

This is Slavoj Žižek—timeless, ever-engaging, and ensuring you won’t be bored when listening to him. Instead, he invites you to dive deep into the dizzying world of intellectual discourse.

I decided to limit this conversation to eight major questions and twelve key words at the end. Stopping Slavoj from answering any question was challenging; he has a natural inclination to talk, but I believe that’s the nature of this profoundly honest philosopher who attracts minds from across the globe. In Sri Lanka, some social groups embraced Slavoj’s ideological perspectives, but I don’t think they penetrated deeply enough among the youth and other social segments thirsty for real structural change. These groups not only indulge in political vulgarity but also shy away from much-needed ideological-based social discourse. Meanwhile, certain groups and individuals confine themselves to their comfort zones, avoiding engagement with the pressing social and economic issues in society.

During our intriguing conversation, my interlocutor expressed an initial assurance of what he humorously referred to as ‘Stalinist freedom.’ He playfully remarked, ‘I will allow you to exercise Stalinist freedom, where I talk without hesitation, and you can sharply censor my words.’ This prompted my first question, wherein I inquired what Slavoj Žižek’s opening lines would be if he had the opportunity to confront Joseph Stalin during his era.

To my surprise, he responded, ‘I think he’s not personally a bad guy, but he caused an irreversible catastrophe for the left. While so-called Stalinism is discredited as a serious idea in new socialist borders, I’m not sure if I’d have enough courage to do it, but if invited to meet him somehow, even at the risk of being liquidated instantly, I’d like to take the chance to kill him. Yes, I will kill him,’ he declared.

However, what interests him the most is the opportunity to meet Vladimir Lenin at the end of his life and ask him, “Was he still aware of what a monster he was creating?” Slavoj says that while Stalin isn’t stupid, he lacks a profound decree. People often anticipate that someone as super powerful as a dictator is possessed of some deep metaphysical wisdom. For instance, during the Khmer Rouge’s dominance in Cambodia (Kampuchea), they claimed that Pol Pot was highly educated in Buddhism and even attained Nirvana, arguing that it explained how he could be a monstrous leader yet appear kind in person. Slavoj rejects this argument, stating, “I don’t buy into this. I don’t think we should look for some deep, even diabolic wisdom in brutal dictators.”

This leads me to my next question, as Slavoj has not only spoken about Western philosophy but also expressed his understandings of Buddhism and how it influences both itself and society, including the West. I asked him how Buddhist monks can effectively navigate involvement in politics while addressing societal challenges and avoiding ideological pitfalls.

“It is no less different for them than for others. Having studied a bit of the history and presence of Buddhism and being aware of the danger of speaking from my European standpoint, I have examined what is gaining popularity now, not only in the East but also in the West—Buddhist economists. One in the West, I believe, is E. F. Schumacher, who wrote ‘Small Is Beautiful’ along those lines. I am skeptical here. It is easy to see the insights propagated by Buddhist economists, although I don’t consider it a closed teaching.

Some of their advice is pragmatically interesting, offering non-violent, utopian claims on how to radically change society. However, I always look at this with a critical eye. For instance, when their ideas were challenged and asked to prove their effectiveness, they often mentioned Bhutan, a country known for maintaining Gross National Happiness. Yet, in the early nineties, didn’t they conduct a fairly sharp ethnic cleansing? They expelled the Lhotshampa or Nepalese minority, which is precisely contrary to Gross National Happiness. It’s always a problem,” he observed.

Slavoj believes that a serious problem emerged right after Buddha’s death, where tendencies arose to seek accommodation with those in power. “Even in the case of Sri Lanka, feel free to correct me if I’m wrong, as I don’t buy into most of the Western media narratives. There were certain ways in which the Buddhist majority could have acted differently when it came to minority issues.

The irony is that true Buddhists understand this and never take things at face value. Buddhism cannot be conceived as a religion in the Western sense. We must remember that Buddha was explicitly agnostic about suffering, seeing it as a fundamental aspect of life, and his focus was on how to alleviate suffering rather than delving into great metaphysical questions,” he said.

“I would say that, in my references to Zen Buddhism in Japan most of the time, which defended Japanese colonization, there is much to learn from Buddhism today to address certain issues like ecological catastrophe—not just by advocating “not to kill worms,” but by taking individual responsibility to address the consequences of capitalism and its dynamics. Buddhism, in its original forms—not some kind of fanatical view on renouncing life to potentially become monks and seek Nirvana—is a wonderful pragmatic and agnostic view. From its very inception, Buddhism detected the falsity of excessive social engagements not driven by progressive causes but by expansionism and the like. Buddhism should do more in this regard. I would say that it’s not just for monks; even ordinary people who follow Buddhism can contribute. You don’t have to act like a perfect monk, but maintaining common decency is essential. What saddens me today is that this fundamental aspect is disappearing more and more from society,” he asserted.

“Today, we witness new forms of evil that present themselves as good, but in challenging situations like war and social upheaval, the greatest danger lies in abandoning our fundamental human kindness. In such circumstances, the idea of being brutal becomes prominent. This is where Buddhism can help, as Buddhism has never endorsed this approach,” Slavoj stated.

My next question was whether there is such a thing as a “just society,” or if it’s merely a collective myth we fool ourselves with. However, for Slavoj, the problem lies in defining what we mean by a just society. The traditional idea, originating not in the West but from Buddha, viewed justice as everyone having their designated place, such as workers being good workers, mothers being good mothers, and so on.

But both in Buddhism and later in Christianity, in their original forms, there emerged a more radical egalitarian space advocating the idea of equality, where everyone has a social space. The most crucial aspect is expanding this egalitarian space without resorting to violence, as any attempt at violence only reinforces brutal hierarchies. Therefore, the first step towards a just society is to clarify the meaning of justice by understanding what justice truly is, he argued.

In our increasingly AI-shaped world, the question arises: should we fear the rise of “Artificial Idiocy”? Will machines not only surpass humans in intelligence but also in their ability to make absurd mistakes? According to Slavoj, these machines are indeed making mistakes, but what matters is how we define “Absurd Mistakes.” As he tried to develop in his book “Hegel in A Wired Brain,” human intelligence is not simply about quick calculations and solving certain complex issues; it excels when it comes to making productive mistakes that lead to something new and higher. For instance, French cuisine’s most celebrated dishes often originated from something going wrong, like French cheese that started to smell.

Instead of discarding it, they embraced the new form. The same happened with wines. This capacity to use mistakes productively and elevate from them is something he doubts AI can achieve. Machines can make mistakes, but they lack the ability to utilize those mistakes to create something better. He takes a more vulgar example, like seduction, where he believes machines can’t seduce as humans do, not because of intelligence, but because of the ability to make interesting mistakes. Progress, Slavoj says, occurs only through the productive use of mistakes.

Based on perhaps my superficial phobia of AI, my next question revolved around the possibility of advanced AI engaging in philosophical debates like Slavoj Žižek, while robotic comedians mock human foibles, and AI-driven revolutionary movements fight for workers’ rights and robot liberation. Slavoj dismisses this possibility, explaining that when humans make decisions, they always do so through subjective engagement. He cites his favorite Christian theologian Søren Kierkegaard, who wrote that claiming to be Christian, Buddhist, Jew, or anything else because you compare different religions and find Christian arguments the best is sinful. True understanding of religious arguments can only occur when you believe in something expediently. Similarly, when it comes to love, you cannot say you compare different individuals and selected the best. Love doesn’t work that way; it’s based on finding adorable qualities that others might not even recognize. He believes that, at least for now, as nobody knows what the future holds, machines are incapable of engaging in proper subjective engagement where they discover reasons rather than merely comparing them because they are searching for the right reason.

In this sense, I don’t believe machines can fight for workers’ rights and similar causes. Engaging in workers’ rights requires an existential understanding of suffering, such as exploitation and manipulation, which cannot be reduced to objective scientific insights. I admit I may not be overly optimistic, but that’s my view,” he asserted.

Many discussions revolve around the loss of privacy due to the latest surveillance technology and social media. I asked Slavoj about the danger of governments and corporations gathering vast amounts of personal data, leading us to sacrifice privacy for convenience. He responded, “I’m unlike many others who fear losing privacy. I don’t mind if some machines know my personal details, but what worries me most is the privatization of our data. We don’t know what they know or what they do with that data. Our focus should not be solely on defending privacy, as more and more machines will gather data and analyze our needs, such as health. What concerns me is the privatization of our data and shrinking public space.”

As virtual reality becomes more prevalent in our lives, I asked Slavoj about the safeguards needed to prevent the distortion of reality and preserve authentic human experiences. He explained, “What we experience as social reality is already, in some sense, virtual. I’m not denying the existence of reality, but what we perceive as reality is already mediated through a virtual symbolic system. Take the recent movie Oppenheimer, for example. The horror of a nuclear explosion is something that exceeds our notion of everyday reality. The distortion in virtual media doesn’t target some pure, innocent reality; it affects the authentic virtual reality of the system in which we live. Authenticity, for me, is not merely looking into oneself; it involves identifying with a certain heroic engagement. The problem with digital media is that they are becoming less and less virtual. Instead of offering metaphors, alluded meanings, and ambiguity, they strive for a perfect copy of reality itself. Take video games as an example—they immerse you in another reality, but in doing so, they lose this authentic virtual quality.”

As we near the conclusion of this intriguing conversation, I asked Slavoj about escaping consumerist culture and finding authentic freedom, as discussed in his critiques of capitalism. He replied, “I’m more pessimistic about this. We live in a global capitalist society where we appear to be increasingly free. On one hand, we are treated as free, but at the same time, we are part of a social world that is obscured and non-transparent. So, we need to clarify what we mean by freedom. I don’t believe we should oppose freedom, discipline, and social order. Abstractly, freedom might mean doing whatever we want, but I wouldn’t want to live in such a society because it would be a horrible world if we couldn’t trust each other to respect basic rules of decency. True freedom requires explicit and implicit rules to be in operation.”

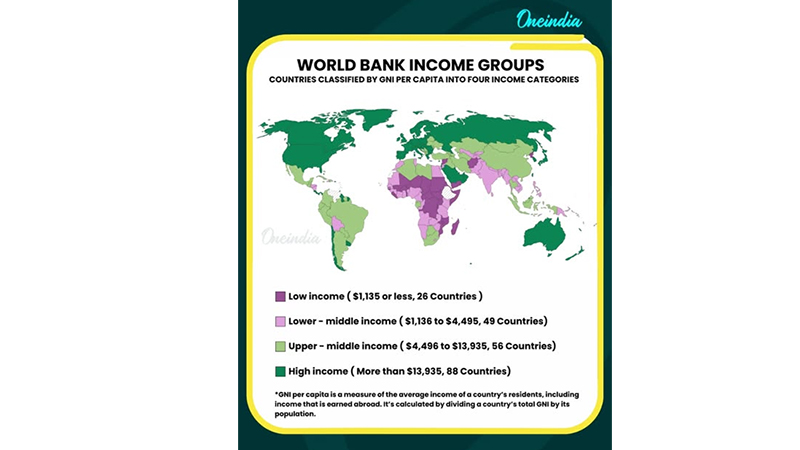

Regarding consumerism, he added, “When you talk about the upper middle-class, the problem might be consumerism, but for a poor person, the issue is getting new clothes and adequate food. We shouldn’t criticize poor people for consumerism when they finally get a bit of money to buy something they need. Let them have a bit of pleasure. For me, the crucial aspect, in a Hegelian sense, is that freedom has to be concrete. Freedom means being free within a certain space, which is why we should strive for socialist democracy as leftists. We must understand that freedom has material conditions. I’m not advocating for a totalitarian state regulating every aspect of life. I like the form of freedom, but to achieve it, a full concrete network of state regulations, unwritten rules, and customs must be well established. Unfortunately, this is something people tend to forget today.

During the final part of our conversation, we delved into several issues, including multiculturalism, the idea of a multi-polar world, the hypocritical behavior of Western hegemony, and the brutal sexual exploitation faced by some Muslim women who are forced to cover their faces to protect their privacy, yet suffer abuse within their homes, rendering their privacy futile. Slavoj expressed his belief in the universality as a driving force to promote respect for each culture. “There must be freedom for me to come over there when I have a problem, and you must have the freedom to come over here when you have a problem in the place where you live. That’s how the idea of this multi-polar world or multiculturalism is possible,” he emphasized. “Not the way by romanticizing and pleasing each other’s oppressions in the country they control.”

Features

The middle-class money trap: Why looking rich keeps Sri Lankans poor

Every January, we make grand resolutions about our finances. We promise ourselves we’ll save more, spend less, and finally get serious about investments. By March, most of these promises were abandoned, alongside our unused gym memberships.

Every January, we make grand resolutions about our finances. We promise ourselves we’ll save more, spend less, and finally get serious about investments. By March, most of these promises were abandoned, alongside our unused gym memberships.

The problem isn’t our intentions, it’s our approach. We treat financial management as a personality flaw that needs fixing, rather than a skill that needs the right strategy. This year let’s try something different. Let’s put actual behavioural science behind how we handle our rupees.

Based on the article ‘Seven proven, realistic ways to improve your finances in 2026’ published on 1news.co.nz, I aim to adapt these recommended financial strategies to the Sri Lankan context.” Here are seven money habits that work because they’re grounded in how humans actually behave, not how we wish we would.

While these strategies offer useful direction for strengthening personal financial management, it is important to acknowledge that they may not be suitable for everyone. Many households face severe financial pressure and cannot realistically follow traditional income allocation frameworks, such as the well-known but outdated Singalovada Sutta guidelines, when even meeting daily food expenses has become a struggle. For individuals and families who are burdened by escalating costs of essentials, including electricity, water, mobile connectivity, transport, and other non-negotiable commitments, strict adherence to prescriptive models is neither practical nor fair to expect. Therefore, readers should remain mindful of their own financial realities and adapt these strategies in ways that align with their income levels, essential obligations, and broader personal circumstances.

1. Your Money Problems Aren’t Moral Failures, They’re Data Points

When every rupee misspent becomes evidence of personal failure, we stop looking for solutions. Shame is a terrible problem-solver. It makes us hide from our bank statements, avoid difficult conversations, and repeat the same mistakes because we’re too embarrassed to examine them.

Instead, try replacing judgment with curiosity. Transform “I’m terrible with money” into “That’s interesting, why did I make that choice?” Suddenly, mistakes become information rather than indictments. You might notice you overspend at Odel or high-end restaurant when stressed about work. Or that you commit to expensive plans when feeling socially pressured. Perhaps your online shopping peaks during power cuts when you’re bored and frustrated.

2. Forget the Year-Long Marathon, Focus on 90-Day Sprints

A Sri Lankan year is densely packed with financial obligations: Sinhala/Tamil Avurudu, Christmas, Vesak, and Poson celebrations; recurring school fees; seasonal festival shopping; wedding and almsgiving periods; yearend festivities; and an evergrowing list of marketing-driven occasions such as Valentine’s Day, Father’s Day, Mother’s Day, and many others. Each of these events carries its own financial weight, often placing additional pressure on already-stretched household budgets.

Research consistently shows that shorter time frames work better. Ninety days is long enough to create a meaningful change, but short enough to maintain focus and momentum. So instead of one overwhelming annual goal, give yourself four quarterly upgrades.

In the first quarter, the focus may be on organising your contributions toward key duties and responsibilities, while also ensuring that you are maximising the available benefits for your designated beneficiaries. Quarter two could be about building a small emergency fund, even Rs. 10,000 provides breathing room. Quarter three might involve auditing your bills and subscriptions to eliminate unnecessary expenses. Quarter four could be when you finally start that investment you’ve been postponing. You don’t need superhuman discipline or complicated spreadsheets, just focused attention, one quarter at a time.

3. Make One Decision That Eliminates Weekly Worry

The best money decisions are the ones you make once but benefit from repeatedly. These are decisions that permanently reduce what behavioural economists call “decision fatigue”, the mental exhaustion that comes from constantly managing money in your head. What’s one choice you could make today that would remove a recurring financial worry?

It might be setting up an automatic standing order to transfer Rs. 10,000 to savings the day your salary arrives, before you can spend it. Maybe it’s consolidating your scattered savings accounts into one that actually pays decent return.

These aren’t dramatic moves that require personality transplants. They’re structural decisions that work with your human tendency toward inertia rather than against it. Most banks now offer seamless digital automation. You can set it up once and benefit from that decision every single month without additional effort or willpower. You make the decision once. You benefit all year. That’s leveraging your energy intelligently.

4. Stop Spending on Who You Think You Should Be

Sri Lankan society comes with heavy expectations. The car you drive, the school your children attend, the hotels you patronise, the brands you wear, all communicate your worth, or so we’re told. Much of our spending isn’t about actual enjoyment. It’s about meeting unspoken expectations, keeping up appearances, or aspiring to a version of us that doesn’t actually exist.

We buy expensive saris we’ll wear once because everyone does. We maintain memberships to clubs we rarely visit because it looks good. We say yes to weekend plans at overpriced restaurants because declining feels like admitting we can’t afford it. We upgrade phones not because ours stopped working, but because others have.

Before your next purchase, ask yourself: do I actually want this, or do I want to want it? If it’s the second one, walk away. You won’t miss it. This isn’t about deprivation, it’s about precision. When you stop spending to perform and start spending to support the life you genuinely enjoy, money pressure eases dramatically. Your resources align with your actual values rather than imagined expectations.

Maybe you don’t care about fancy restaurants, but you love long drives along the southern coast. Maybe branded clothing leaves you cold, but you’d spend any amount on art supplies or books. That’s fine. Spend accordingly.

5. Break One Habit, See If You Actually Miss It

We’re creatures of routine, which serves us well until those routines outlive their usefulness. Sometimes we spend money on habits that started for good reasons but no longer serve us. Alpechchathava, in Buddha’s teaching, means living contentedly with few desires. It guides a person to manage money wisely by avoiding excess spending, unnecessary debt, and craving, and by focusing on essential needs and wholesome priorities. In this way, wealth supports mental cultivation, generosity, and spiritual progress.

The daily kottu roti that once felt like a convenient solution after working late may now have turned into an unnecessary routine. Similarly, frequent P&S or Caravan snack runs, and the habit of picking up sugary treats like cakes and sweets, are not only costly but also wellknown to be unhealthy, as nutritionists consistently point out. Beyond food, other expenses such as magazine subscriptions, the monthly coffee meetup, or weekend mall browsing often continue on autopilot without us realising how much they add up. These seemingly small, habitual expenses can quietly drain your budget while offering very little longterm value.

Try this experiment: keep a money diary for one week. Note every expense, no matter how small. Then identify one regular spend and eliminate it for the following week. If you don’t miss it? Excellent, keep it gone. If you genuinely miss it? Add it back without guilt. This isn’t about permanent sacrifice.

It’s about snapping yourself out of autopilot and checking whether your spending still reflects your current reality, priorities and purchasing power. You might discover you’re spending Rs. 15,000 monthly on things you barely notice.

6. Create Your Crisis Playbook on a Good Day

Many financial disasters don’t happen because we’re careless, they happen because we’re panicked. When crisis strikes, job loss, medical emergency, unexpected business downturn, fear hijacks our decision-making. Our rational brain exists while panic makes expensive choices: high-interest personal loans, selling investments at losses, making commitments we can’t sustain.

The solution? Make your crisis plan before the crisis arrives. On a calm day, sit down and document: If I lost my income tomorrow, what would I do first? Which expenses are truly essential? What’s the absolute minimum I need to function? Who could I call for advice? Which savings are untouchable, which could be accessed if necessary? What government support or loan restructuring options exist (Not in Sri Lanka)? This is a sort of preparation for sudden shocks.

7. Question the Money Stories You Inherited

Sometimes our biggest financial obstacles aren’t failed attempts, they’re the attempts we never make because we’ve internalised limiting stories. “Our family was never good with money.” “Investing is for rich people.” “I’m just not the type who earns more.” “Women don’t understand finance.” These narratives, absorbed from family, culture, or past experiences, become invisible fences.

Question them. Where did this belief originate? Is it actually true, or is it a story you’ve been telling yourself for so long, it feels like fact? What would happen if you tested it? Often, these stories protect us from the discomfort of trying and potentially failing. But they also protect us from the possibility of succeeding. And that’s a far costlier protection than most of us realise.

The Bottom Line

Improving your finances in 2026 doesn’t require becoming a different person. It requires understanding the person you already are, your patterns, triggers, and tendencies, and working with them rather than against them.

These aren’t magic solutions. They’re evidence-based approaches that acknowledge a simple truth: you’re not broken, and your money management doesn’t need fixing through willpower alone. It needs better systems, clearer thinking, and a lot less shame.

Features

Public scepticism regarding paediatric preventive interventions

A significant portion of the history of paediatrics is a triumph of prevention. From the simple act of washing hands to the miracle of vaccines, preventive strategies have been the unsung heroes, drastically lowering child mortality rates and setting the stage for healthier, longer lives across the globe. Simple measures like promoting personal hygiene, ensuring the proper use of toilets, and providing Vitamin K immediately after birth to prevent dangerous bleeding, have profound impacts. Advanced interventions like inhalers for asthma, robust trauma care systems, and even cutting-edge genetic manipulations are testament to the relentless and wonderful progress of paediatric science.

A shining beacon that has signified increased survival and marked reductions in mortality across the board in all paediatric age groups has been the development of various preventive strategies in the science of children’s health, from newborns to adolescents. The institution of such proven measures across the globe, has resulted in gains that are almost too good to be true. From a Sri Lankan perspective, these measures have contributed towards the unbelievable reduction of the under-5-year mortality rate from over 100 per 1000 live births in the 1960s to the seminal single-digit figure of 07 per 1000 live births in the 2020s.

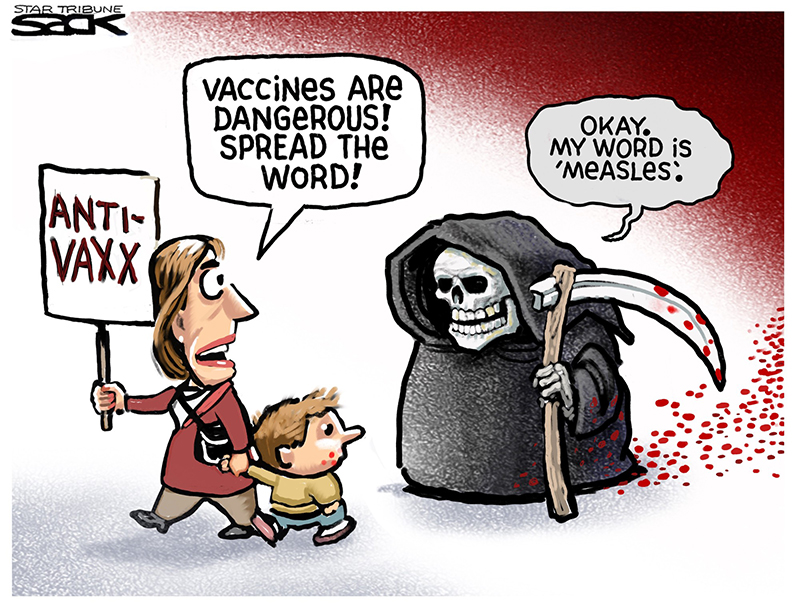

Yet for all this, despite the overwhelming evidence of success, a most worrying trend is emerging. That is public scepticism and pessimism regarding these vital interventions. This doubt is not a benign phenomenon; it poses a real danger to the health of our children. At the heart of this challenge lies the potent, often insidious, spread of misinformation and disinformation.

The success of any preventive health strategy in paediatrics rests not just on its scientific efficacy, but on parental cooperation and commitment. When parents hesitate or refuse to follow recommended guidelines, the shield of prevention is compromised. Today, the most potent threat to this partnership is the flood of false information.

Misinformation is false information spread unintentionally. A well-meaning friend sharing a rumour about a vaccine side-effect they heard online is spreading misinformation.

Disinformation is false information deliberately created and disseminated to cause harm or sow doubt. This often comes from organised groups or individuals with vested interests; sometimes financial, sometimes ideological, who seek to undermine public trust in medical institutions and scientific consensus.

The digital age, particularly social media, has become the prime breeding ground for these falsehoods. Complex scientific data is reduced to emotionally charged, simplistic, and often sensationalist soundbites that travel faster and farther than the truth.

The most visible battleground is childhood vaccination. Decades of robust, high-quality research have confirmed vaccines as one of the most cost-effective and successful public health interventions ever conceived. Global vaccination efforts have saved an estimated 150 million lives in the past 50 years, eradicating or drastically controlling diseases like polio, measles, diphtheria, and tetanus.

However, a single, long-retracted, and scientifically debunked paper claiming a link between the Measles-Mumps-Rubella (MMR) vaccine and autism continues to be weaponised by disinformation campaigns. This persistent myth, despite being soundly disproven, taps into deep-seated fears about children’s development. Other common vaccine myths target ingredients such as trace amounts of aluminium or mercury, which are harmless in the quantities used and often less than what is naturally found in food or the idea that “natural immunity” from infection is superior, totally ignoring the fact that natural infection carries the devastating risk of severe complications, long-term disability, and even death. The tangible consequence of this doubt is the dropping of childhood vaccination rates in various communities, leading to the wholly unnecessary re-emergence of vaccine-preventable diseases like measles.

Scepticism is not limited to vaccines. It can touch any area of paediatric preventive care where an intervention might seem unnecessary, invasive, or have perceived risks. Routine screenings for speech disorders, motor skills, or mental health issues can sometimes be perceived as medicalising normal childhood variations or putting a “label” on a child. Parents may resist or delay screening, missing the critical window for early intervention of proven measures that are likely to help. Advice on managing childhood obesity, reducing screen time, or adopting a balanced diet can be viewed by some parents as intrusive or judgmental, leading to poor adherence to essential health-promoting behaviours.

The regular use of inhalers for asthma or other chronic conditions might be looked down upon due to the fear of “dependency”, “addiction”, or long-term side effects, despite medical consensus that these preventive measures keep conditions controlled and prevent life-threatening exacerbations.

The common thread is a lack of understanding of the risk-benefit ratio. Parents, bombarded by fear-mongering narratives, often overestimate the rare, mild risks of an intervention while catastrophically underestimating the severe and permanent risks of the disease or condition itself.

The power of paediatric preventive medicine is not in a single shot or pill, but in the consistent, committed partnership between healthcare providers and parents. Paediatric science, driven by rigorous evidence-based medicine, do continue to refine guidelines, conduct transparent research, and communicate its findings clearly. When guidelines are confusing or lack robust evidence, it naturally creates openings for doubt. The scientific community’s commitment to continuous quality improvement and accessibility is paramount.

Ultimately, the success of prevention rests with the parents. Parenting, as a vital form of preventive care, includes all activities that raise happy, healthy, and capable children. The simple, non-medical steps mentioned in the introduction, proper handwashing, good sanitation, and encouraging exercise, are all forms of parental preventive intervention.

For more complex interventions, parental commitment requires several actions. They need to seek and trust the guidance provided by qualified healthcare professionals over anonymous, unsubstantiated online claims. They need to engage in an open dialogue by asking relevant questions and expressing concerns to doctors in an open, non-confrontational manner. A good healthcare provider will use this as an opportunity to educate and build trust, and not a portal to simply dismiss concerns. Then, of course, there is the spectre of adherence to various protocols and actions by the parents. These include consistently following recommended schedules, whether for well-child checkups, vaccinations, or daily medication protocols.

Addressing public scepticism requires a multi-pronged, collaborative strategy. It is not just about correcting false facts (debunking), but about building resilience against future falsehoods (prebunking). The single most influential voice in a parent’s decision-making process is their paediatrician or primary care provider. Clinicians must move beyond simply reciting facts. They need to use empathetic communication techniques, like Motivational Interviewing (MI), which focuses on active listening, validating parental concerns, and then collaboratively guiding them toward evidence-based decisions. For example, responding with, “I hear you’re worried about the side-effects you read about. Can I share what we know from decades of safety monitoring?” Being open about common, minor side effects such as a short-lasting fever after a vaccine pre-empts the shock and distrust that occurs when an expected, yet unmentioned, reaction happens.

Public health campaigns must go on the offensive, not just a defensive fact-checking spree. Teaching the general public how disinformation works, the use of “fake experts”, selective cherry-picked data, and conspiracy theories all add up to a most powerful form of inoculation (prebunking) against future exposure. Health institutions must simplify their communications and make verified, high-quality information easily accessible on platforms where parents are already looking.

Parents often trust their peers as much as their doctors. Engaging local community leaders, faith leaders, and even trusted social media influencers to share accurate, positive messages about paediatric health can shift the public narrative at a grassroots level. While protecting privacy, sharing aggregate data and stories about the dramatic decline in childhood diseases thanks to prevention can re-emphasise the collective good.

The battle against child mortality and morbidity has been one of the great human achievements, a testament to scientific ingenuity and collective effort. Today, the greatest threat to maintaining these gains is not a new virus, but a breakdown of trust fuelled by unchecked falsehoods.

Paediatric preventive interventions, from a cake of soap and a proper toilet to the most sophisticated genetic therapies, are the foundation of a healthy future for every child. To secure this future, the scientific community must remain transparent, the healthcare system must lead with empathy, and the public must commit to informed, critical thinking. By rejecting the noise of disinformation and embracing the clear, evidence-based consensus of science, we can ensure that every child continues to benefit from the life-saving progress that defines modern paediatrics. The well-being of the next generation demands nothing less than this renewed commitment.

Little children are not in a position to make abiding decisions regarding their health, especially regarding preventive strategies in health. It is ultimately the crucial decisions made by responsible parents regarding the health of their children that really matter. As doctors, our commitment is never to leave any child behind.

by Dr B. J. C. Perera ✍️

MBBS(Cey), DCH(Cey), DCH(Eng), MD(Paediatrics), MRCP(UK), FRCP(Edin), FRCP(Lond), FRCPCH(UK), FSLCPaed, FCCP, Hony. FRCPCH(UK), Hony. FCGP(SL)

Specialist Consultant Paediatrician and Honorary Senior Fellow, Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Joint Editor, Sri Lanka Journal of Child Health

Section Editor, Ceylon Medical Journal

Features

Attacks on PM vulgar, misogynistic; education reforms welcome

We express our profound concern and deep outrage at the vulgar, misogynistic, and defamatory attacks being directed at the Prime Minister and Minister of Education, Dr. Harini Amarasuriya.

Dr. Harini Amarasuriya is not merely a political leader; she is a scholar, public intellectual, and lifelong advocate of social justice, equality, and education. Attempts to discredit her through personal abuse rather than reasoned policy debate are not only an insult to her, but an assault on democratic values, women’s leadership, and intellectual integrity in public life.

Such attacks are unjust and unethical, and they corrode democratic discourse. We are deeply disappointed that certain political actors and their supporters continue to rely on misinformation, prejudice, and emotional manipulation, instead of engaging in rational, evidence-based, and constructive debate.

Sri Lanka has already paid a heavy price for decades of politics rooted in fear, communal division, and sentiment-driven populism. The country’s economic collapse and social breakdown are the direct consequences of these failed approaches. The people decisively rejected this style of politics through the Aragalaya, signaling a clear demand for change. Sri Lanka now stands at a historic turning point. After decades of corruption, ethnic manipulation, and policy paralysis, the people have given a clear mandate for systemic reform.

At this critical moment, Sri Lanka urgently needs structural reforms, particularly in education, which is the foundation of long-term national development, social mobility, and global competitiveness. Yet we observe that the very forces responsible for the country’s decline are once again attempting to block or derail reforms by exploiting religious, cultural, and emotional narratives.

We strongly affirm that no nation can be rebuilt through hatred, fear, or division. Education reform is not a political threat; it is a national necessity. Efforts to undermine reform through personal attacks and manufactured controversies serve only those who seek to return to power by keeping the country weak, divided, and intellectually impoverished.

Those who now attack Dr. Harini Amarasuriya are not defending culture or morality. They are defending privilege and political survival. Having failed the country for over seventy-five years through communalism, patronage, and anti-intellectualism, they now fear that an educated, critical, and empowered generation will render their outdated politics irrelevant.

This is why they target:

=a woman,

=an academic,

=and a reformer.

We therefore state clearly that we:

1. Condemn all forms of character assassination, gender-based attacks, and hate propaganda against the Prime Minister and Minister of Education.

2. Affirm our full support for Dr. Harini Amarasuriya’s leadership in advancing Sri Lanka’s education reforms.

3. Urge the government to proceed firmly and without retreat in implementing the proposed education reforms, in line with national policy and the public mandate.

4. Call upon academics, professionals, teachers, parents, and citizens to stand together against reactionary forces that seek to sabotage reform through fear mongering and disinformation.

A country cannot be rebuilt by those who destroyed it. A future cannot be created by those who fear education reforms.

Sri Lanka’s future must not be sacrificed for the ambitions of a few.Sri Lanka must move forward — with knowledge, dignity, and courage.

Signatories:

1. Markandu Thiruvathavooran, Attorney at law

2. S. Arivalzahan, University of Jaffna

3. Dr S.Ramesh, University of Jaffna

4. Dr. Mariadas Alfred, Former Dean, University of Peradeniya

5. Prof B.Nimalathasan, Senior Professor, University of Jaffna

6. S. Srivakeesan, Station Master, SriLankan Railways

7. A. T. Aravinthan, Branch Manager, Commercial Bank

8. Dr. S. Niththiyaruban, Paediatrician, Teaching Hospital, Jaffna

9. Dr. S. Selvaganesh, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeon, Teaching Hospital, Jaffna

10. Dr. S. Mathievaanan, Consultant Surgeon, Teaching Hospital, Jaffna

11. Prof. P. Iyngaran, University of Jaffna

12. Eng. M. Sooriasegaram, President, Education Development Consortium

13. Dr. S. Raviraj, Senior Consultant Surgeon, Former Dean, Faculty of Medicine, University, Jaffna.

14. Mr. Saminadan Wimal, University of Jaffna

15. Dr. A. Antonyrajan, University of Jaffna

16. P. Regno, Attorney at Law

17. Prof. J. Prince Jeyadevan, University of Jaffna

18. Prof. S. Muhunthan, University of Jaffna

19. Prof. R. Kapilan, University of Jaffna

20. Dr. S. Jeevasuthan, University of Jaffna

21. J.S. Thevaruban, University of Jaffna

22. S. Balaputhiran, University of Jaffna

23. Dr. N. Sivapalan, Retired Senior lecturer, University of Jaffna

24. I. P. Dhanushiyan, University of Jaffna

25. Dr. K. Thabotharan, University of Jaffna

26. Dr. Bahirathy J. Rasanen, University of Jaffna

27. Perinpanayagam Ronibus, Vice Secretary, Change Charitable Trust, Jaffna

28. Dr. S. Maheswaran, University of Peradeniya

29. Mr. S. Laleesan, Principal, Kopay Teachers’ College

30. Victor Antany, Teacher, Kilinochchi

31. K. Shanthakumar, Principal, Technical College, Vavuniya

32. S. Thirikaran, Principal, J/ Puttur Srisomaskanda College

33. Dr. T. Vannarajan, Advanced Technical Institute, Jaffna.

34. X. Don Bosco, Resource person, Piliyandala Educational Zone

35. K. Ravikumar, Regional Manager, Powerhands Pvt Ltd

36. Sathiyapriya Jeyaseelan, DO, Economist

37. A. Kalaichelvan, Chief Accountant, Animal Productive & Health

38. C. Vathanakumar, Retired Project Director

39. P. Kirupakaran, Department of Buildings (NP)

40. A. Antony Pilinton, David Peris Company, Jaffna

41. A. Muralietharan, Social Activist

42. Sinthuja Sritharan, Independent Researcher

43. T. Sritharan, Social Activist

44. Ms. Gnasakthi Sritharan, Social Activist

45. P. Thevatharsan, Management Service Officer

46. . S. Mohan, Social Activist

47. K. Jeyakumaran, Social Activist

48. Dr. N. Nithianandan, Chairman, Ratnam Foundation

49. George Antony Cristy, Social Activist

50. S. Thangarasa, Social Activist

51. N. Bhavan, Retd. Deputy Principal, Mahajana College

52. P. Muthulingam, Executive Director, Institute of Social Development, Kandy

53. M.K. Sivarajah, Social Activist

54. Mr. V. Sivalingam, Human Rights Activist

55. S. Jeyaganeshan, Samuthi Development Officer

-

Editorial4 days ago

Editorial4 days agoIllusory rule of law

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoUNDP’s assessment confirms widespread economic fallout from Cyclone Ditwah

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoKoaloo.Fi and Stredge forge strategic partnership to offer businesses sustainable supply chain solutions

-

Editorial5 days ago

Editorial5 days agoCrime and cops

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoDaydreams on a winter’s day

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoThe Chakka Clash

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoSurprise move of both the Minister and myself from Agriculture to Education

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoExtended mind thesis:A Buddhist perspective