Midweek Review

‘Catholic Action!’:

Nun Other Than; The Chithra Bopage Story by Udan Fernando

Reviewed by Laleen Jayamanne

Udan Fernando, though unknown to me, wrote to ask if I would write a piece on his new film, adding that it was about a Lankan woman who was once a nun and also involved with the JVP, now living in Australia. As a lapsed Roman Catholic, living in Australia, taught by nuns (both Irish and Lankan), with friends who were enthusiastic nuns, I was intrigued, but to write I had to be moved in some way by the film, I said.

I found the archival photos and images documenting the era of the JVP in the 70s and 80s, and also the family photographs moving, as they now carry memory-traces of a deep history of religious and political idealism and historical violence in Lanka within living memory.

‘Nun Other than; The Chithra Bopage Story’ has been screening in different forums in Colombo and Jaffna just before the presidential election. I have just watched it alone on my computer. There is something a little sad about not being able to see this film with other Lankans well disposed towards its rather unusual ambitions. After all, in a Sinhala-Buddhist majoritarian country how many would find a ‘nun’s story’ interesting! Hollywood of course made A Nun’s Story with Audrey Hepburn working in Africa, which was a hit. I recall having seen it with my parents at the Liberty. Then, there is the great British director, Michael Powell’s magnificent technicolour classic of the tragic emotional turmoil among white nuns, set in a remote convent perched precariously high up on a Himalayan crag, called Black Narcissus (‘47). A Catholic priest, I think Father Noel Cruz, made a lively 16mm film set in the slums about a bicycle, I think, in the 60s. Apart from that and of course, the Catholic, Lester James Peiris’ contribution to the Lankan cinema, the internal spiritual-ethical social values of Christianity and its modern institutional ethos (post Vatican 2 reforms), have not been material for cultural production in Lanka, as far as I am aware. I am thinking here about the 60s, and a part of the 70s, when I lived there or visited regularly for research on the Lankan cinema.

Nun Other Than; The Chithra Bopage Story is a ninety-minute Docu-Drama in English and Sinhala by Udan Fernando, who has made several documentary films and has lived and worked overseas for many years. The documentary part is structured on the central figure of Chithra (Mudalige) Bopage, now living in Melbourne, Australia with her husband, Lionel Bopage, who was, between 1978 and 1984, the General Secretary of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) in its second iteration. Chithra recounts her life in Lanka as a young girl and how she decided to become a Roman Catholic nun, having observed as a patient herself, foreign (white), nursing-nuns working in the General hospital with a great sense of care and kindness to the patient. I remember these nuns well and the last of them who worked with dedication at the ‘Leprosy-asylum’ at Hendala, with its very high walls.

The dramatic re-enactment consists of Chithra’s life as a young novice and nun and her early married years after she left the religious order. The film is basically in the genre of ‘Talking-Heads’ with key figures in Chithra’s life, like her elder sister Rohini and brother Kingsley Mudalige and wife Shyama and a delightful nun, Sr Noel Christine Fernando, who was a confident, conveying a vivid sense of Chithra as a spirited and highly focused young girl and woman with a strong sense of social justice and a passion for singing, with a voice to match it.

Lionel and Chithra Bopage with Nirmala Rajasingham at the Jaffna screening

Importantly for me, through these reminiscences, we come to know not only Chithra, but also the liberal ethos of her Roman Catholic family, their easy bilingualism, their openness to the world, a certain Humanist ‘Catholicism’, which means ‘Universal’, not narrowly parochial. I found the absence of any residue of feudal attitudes in Chithra’s family an eye-opener, as I myself come from a Catholic family, with deep roots in Catholic villages, which had some deplorable feudal values, despite being bilingual and my parents also having been educated by religious clergy. The way Chithra’s mother agrees to her becoming a nun (though her clear preference was for her to get married), is one example of this liberalism, and the other being, her attitude to Chithra leaving the religious order to marry Lionel.

It’s not to her liking either and is willing to find another ‘suitable’ person for her, but accepts it, respecting Chithra’s choice. However, her mother is fully there to help out when she takes up the care of her granddaughter, so as to lessen the burden on Chithra at the time when Lionel is unlawfully held in custody without cause. This tolerant and open-minded attitude of Chithra’s Catholic family from Avissawella is a remarkable aspect in our Lankan culture and a real tribute to her parents and siblings. Her siblings and sister-in-law who lovingly talk about Chithra on camera, also have very open attitudes to interpersonal relations between the sexes and are remarkably non-judgemental about Chithra’s choices and admire her courage and her considerable singing talent. I find all of them thoughtful, exemplary Lankans.

In the context of the Sinhala cinema, where ‘sexual promiscuity’ is often coded as Christian (e. g. Hansa Vilak, Dekala Purudu Kenek…), in a censorious manner, this relaxed liberalism, openness to differences, focused on in this film, is a breath of fresh air.

This, one might say, is the real, enlightening “Catholic Action,” – to use that screaming political headline of the 60s differently here. I remember its use well, when there were organised protests against the ‘Take-Over of Christian Schools’, by the government. My family was involved in the so-called ‘Catholic Action’, fearing that Christian religious education and values would not be taught when they were incorporated into the government school system. It is ironic that when Lionel decided to leave the JVP for good in ’84, the JVP also called it ‘Catholic Action’, no doubt blaming Chithra’s influence on him.

I find the wedding photos of Chithra and Lionel very moving, especially the one of both of them seated with Lionel’s mother, in a white Kandyan sari, looking directly at the camera with a grave expression. I wonder what she thought of her son’s marriage and politics. The photos of the group of friends all seated eating their rice packets, a modest wedding feast, conveys a sense of community feeling. Lionel’s progressive attitude within the JVP context is seen in his choice of the signatories at their marriage; a Tamil and a Sinhala brother in the party. This multi-ethnic-cultural gesture corresponds to his position on the “National Question’, on which he deviated from the official JVP line, having worked in the North and the East.

Apart from the ‘Talking- Heads’, the film also presents an array of photographs, the most remarkable being those of the JVP in their second phase, after Rohana Wijeweera, Lionel Bopage and the rest were released from prison in 1977. They also include news photos of mass murder and mutilation of bodies in the period of 88-89 terror, in the bloody confrontation between the UNP and the JVP. Some of these images evoke strong feelings while also being informative, given their historical resonances. The timing of the release of this film during the days leading up to the Presidential elections on 21/9/24 will also resonate deeply with many Lankans who lived through the 70s and 80s J. R. Jayewardene era, when the current President, Ranil Wickremesinghe was the Minister of Education during July ‘83.

The interplay between the contemporary Chithra at 77, wearing a mauve straw hat, talking to the camera directly in large close-ups, in Melbourne, Australia and her younger self, slowly gathers a rhythm of sorts, a hesitation there and light-sorrow felt here, thoughtfulness and regret that she can’t remember everything well enough. She wishes that she had written down everything, and so do I. But I do wish that Udan had varied a little the mise-en-scene (i. e. the compositions of the shots) so that we might have been able to see Chithra in her ‘new’ context, Australia, her home for over three decades. The same continuous shot of her in close-up meant that we never got the chance to see her in the country which offered her and her family refuge in the 80s. Apart from the opening establishing-shot of her walking down a tree-lined street full of large white Galah birds typical of Australia, she could have been anywhere. This is a missed opportunity because one is curious to see this remarkable woman in her new context, her adopted, generous country, Australia, which has been very hospitable especially to Lankan intellectuals, scholars, artistes and activists over the years and many, others, too. The discursive information provided of the work Chithra did in Australia doesn’t create a milieu and its rhythms, which would have enriched the film and informed Lankans who might still be rather snooty about Australia and how its egalitarian ethos and values work.

- Director Udan Fernando

One sometimes feels that the director was carried away, enjoying watching the young nun in her crisp pastel blue habit and the sari clad Chithra so much, that the camera lingers on her for a little too long, (cinematically speaking), just enjoying looking at her lovely appearance, in tastefully matching saris, though we hear that Chithra had only two or three saris and that too threadbare. Or more generously, it can be viewed as a nice ‘Brechtian touch! A glimpse of the young Dinara Punchihewa as an actress enjoying her role as Chithra, or so I thought, trying to find an excuse for the duration of these scenes. But then again, they do capture the young Chithra’s quite normal enjoyment of clothes, jewellery and hairstyles, in the life of a fun loving young middle-class girl. Dinara is a very watchable, fresh cinematic presence, in that she conveys through her quietly expressive face and capacity for stillness, a quality of intelligence, which I see as a capacity for introspection, self-reflexivity, which are also linked to Chithra’s religious vocation as a nun.

As young Sisters of Perpetual Help, Chithra showed intellectual interests and was chosen to be trained in working with young people in underprivileged backgrounds. During her training at Aquinas University College, she was expected to research the reasons for the devastating 1971 JVP uprising, and massacre of so many young educated youth of the country. We see her reading a book on it in her room. And it’s this exposure, in a proud Lankan Catholic Higher Education Institution (also my Alma Mater), that makes Chithra question her own privileged life in the convent with three square meals and a pleasant environment. She questioned why people rushed to give her a seat in buses and other such preferential treatment to clergy. It is these thoughts that led her to leave the convent and join the JVP. While Lionel’s presence in her life by then appears to have facilitated this radical move, she asserts that the decision was due to her own firm convictions. Her marriage to Bopage, without informing her own family, was felt as a big upheaval by her brother who added lightly that, ‘it’s something you see in the movies or in a novel, not in normal life!’

The post ‘77 JVP appears as a different organisation from that which led to the April ’71 uprising. Women convened a ‘Conference of Socialist Women’s Union’, at which delegates from Iraq and Palestine were present. Also, a striking difference was the creation of a repertoire of Vimukthi Gee (Songs of Liberation) of the JVP, which drew Chithra to it even before she left the convent. It was a lovely surprise to see a photograph of my late friend Sunila Abeysekera in the group and hear Chithra talk about her with affection.

But the abiding emotional impact of the film comes from the reflective, steadfast consciousness at its heart, Chithra herself at 77, a quietly wonderful presence. That she can talk about the importance of her work as a nun and of her complex feelings so lucidly with ease is again linked, I think, to the ‘Westernised’, bilingual attitudes in her ethos and also at the convent where she was free to confide in a friendly nun who admired Chithra’s decision to leave the convent and also of her ease with the priest who she considered a good friend with whom she felt free to discuss her decision.

These are urbane aspects of a Catholic institutional ethos, after the Ecumenical Council of the 60s. Buddhists unfamiliar with this aspect of Christianity can learn about an ethos free of feudal ideologies. Sinhala- Buddhist ideology appears to re-feudalise institutions and practices (even secular ones) of Lanka, in an alarming way now, thus betraying the universal avihinsa, rational values of Buddhist philosophy itself. In this sense too, the film shows a progressive church with considerable freedom for women to choose alternative ways of living and behaving. Udan himself as a Protestant (Methodist), appears to be fascinated by the institutional architectural richness of the Catholic church interiors, their ritual ornamentation, which Protestantism eschewed with Luther’s Reformation.

Chithra and Lionel’s quite considerable social and religious differences would have become, in a Sinhala genre film, the stuff of melodrama and tragedy. But in Udan’s film we see them age together with grace, as their children grow up in a foreign country, which offered them refuge from the political violence of Lanka. Thus, Australia also shines in having offered refuge and hope to this remarkable couple and their two children.

As I see it, the film is also a tribute to the Ecumenical values (broad sympathy and interests), of the Catholic Church in Lanka, in that it facilitated a rare and happy (romantic), love story of personal steadfastness to each other and to the political and ethical values they stood for, at a time of great danger in Lanka.

One wonders if the film might create a public discourse on the history of the JVP (the role of women and ethnic and religious minorities), in its several iterations.

Midweek Review

AKD’s Jaffna visit sparks controversy

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s (AKD) recent visit to Jaffna received significant social media attention due to posting of a less than a minute-long video of him going for a walk there.

An unarmed soldier was captured walking beside AKD who is also the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces in addition to being the Defence Minister. A soldier carrying an assault rifle was seen walking behind AKD. There was another soldier in a pair of shorts walking just behind the President. AKD’s Personal Security Officer (PSO) was not on that video. By January 26th morning that video received 378 K ‘hits’ and 9.8 K reactions.

AKD was in a pair of shorts and running shoes. There hadn’t been a previous occasion in which AKD was captured in a pair of shorts during his time as a lawmaker or the President. AKD was there on a two-day visit that coincided with Thai Pongal.

AKD’s latest visit to Jaffna for Thai Pongal caused a huge controversy when he declared that those who visited Buddhist shrines there influenced and encouraged hate. “Coming to Jaffna to observe sil on a Poya Day, while passing the Sri Maha Bodhi, is not virtue, but hatred,” AKD declared. The utterly uncalled for declaration received the wrath of the Buddhists. What made AKD, the leader of the JVP, a generally avowed agnostics, as well as NPP, to make such an unsubstantiated statement?

Opposition political parties did not waste much time to exploit AKD’s Jaffna visit to their advantage. They accused AKD of betraying the majority Buddhists in the country. Those who peruse social media know how much AKD’s Jaffna talk angered the vast majority of people aware of the sacrifices made by the armed forces and police to eradicate terrorism.

If not for the armed forces triumph over the LTTE in May 2009, AKD would never have ended up in the Office of the President. That is the undeniable truth. Whatever, various interested parties say, the vast majority of people remember the huge battlefield sacrifices made by the country’s armed forces that made the destruction of the LTTE’s conventional military power possible. Although some speculated that the LTTE may retain the capability to conduct hit and run attacks, years after the loss of its conventional capacity, the group couldn’t stage a comeback, thanks to eternal vigilance and the severity of its defeat.

AKD’s attention-grabbing Jaffna walk is nothing but a timely reminder that separatist Tamil terrorism had been defeated, conclusively. Of course, various interested parties may still propagate separatist views and propaganda but Eelam wouldn’t be a reality unless the government – whichever political party is in power – created an environment conducive for such an eventuality.

The JVP/NPP handsomely won both the presidential and parliamentary polls in Sept. and Nov. 2024, respectively. Their unprecedented triumph in the Northern and Eastern provinces emboldened their top leadership to further consolidate their position therein at any cost. However, an unexpected and strong comeback made by one-time LTTE ally, the TNA, appeared to have unnerved the ruling party. On the other hand, the TNA, too, seems to be alarmed over AKD’s political strategy meant to consolidate and enhance his political power in the North.

Perhaps, against the backdrop of AKD’s Jaffna walk, we should recollect the capture of Jaffna, the heart of the separatist campaign during President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga’s time. Jaffna town was regained in the first week of December, 1995, 11 years before the outbreak of Eelam War IV (August 2006 to May 2009).

Operation Riviresa

In the run-up to the January 2015 presidential election, Kumaratunga, who served two terms as President (1994 to 1999 and 2001 to 2005), declared that her administration liberated 75% of the territory held by the LTTE. That claim was made in support of Maithripala Sirisena’s candidature at the then presidential election. Kumaratunga joined hands with the UNP’s Ranil Wickremesinghe, the JVP (NPP was formed in 2019), the SLMC and the TNA to ensure Sirisena’s victory.

Liberating 75% of territory held by the LTTE was nothing but a blatant lie. That claim was meant to dispute war-winning President Mahinda Rajapaksa’s bid for a third term. Ahead of the 2005 presidential election, Kumaratunga’s administration lost the capacity to conduct large-scale ground offensives in the Northern theatre of operations. In fact, the last major offensive, codenamed Agni Kheelsa in April 2001, had been undertaken in the Jaffna peninsula where the Army suffered debilitating losses, both in men and material. That was President Kumaratunga’s last attempt to flex military muscle. But, she should be credited for whole-heartedly supporting Operation Riviresa (Aug. to Dec. 1995) that brought back Jaffna under government control.

In spite of several major attempts by the LTTE to drive the Army out of Jaffna, the military held on. The largest ever combined security forces offensive, under President Mahinda Rajapaksa, with the Navy and Air Force initiating strategic action against the LTTE and the triumph over separatist terrorism in two months short of three years, should be examined taking into consideration the liberation of the Jaffna peninsula and the islands.

If President Kumaratunga failed to bring Jaffna under government control in 1995 and sustain the military presence there, regardless of enormous challenges, the war wouldn’t have lasted till 2006 and the outcome of the war could have gone the other way much earlier. Whatever the criticism of Kumaratunga’s rule, liberating the Jaffna peninsula is her greatest achievement. Regardless of financial constraints, Kumaratunga and her clever and intrepid Treasury Secretary, the late A.S. Jayawardena, provided the wherewithal for the armed forces to go on the offensive. After the successful capture of Jaffna, by the end of 1995, Kumaratunga ordered Kfirs and MiG 27s, and a range of other weapons, including Multi Barrel Rocket Launchers (MBRLs), to enhance the fire power, but the military couldn’t achieve the desired results. While she provided any amount of jaw, jaw, it was Amarananda Somasiri Jayawardena who ensured that the armed forces were provided with the necessary wherewithal, under difficult circumstances, especially in the aftermath of the later humiliating Wanni debacle, when he was the Central Bank Governor.

AKD is certainly privileged to engage in morning exercises in a terrain where some of the fiercest battles of the Eelam conflict were fought, involving the Indian Army, as well as other Tamil groups, sponsored by New Delhi, in the ’80s.

When the Army secured Jaffna, in 1995, and lost Elephant Pass in 2000, the forward defence lines had to be re-established and defended at great cost to both men and material. By then, the Vanni had become the LTTE stronghold and successful ground offensive seemed impossible but under President Mahinda Rajapaksa’s political leadership the combined armed forces achieved the unthinkable – the annihilation of the LTTE in a way it couldn’t make a comeback at any level. AKD’s post that went viral recently is evidence that peace has been restored and maintained for the Commander-in-Chief to take a walk on a Jaffna street.

Social media comments on AKD’s Jaffna walk reflected public thinking, especially against the backdrop of that unwarranted claim regarding Buddhists influencing hatred by visiting Jaffna on a Poya Day to observe sil, having passed the Sri Maha Bodhi.

UK anti-SL campaign

President Dissanayake taking a walk

It would be pertinent to ask the Sri Lanka High Commission in the UK regarding action taken to counter the continuing propaganda campaign against the country. Sri Lankan HC in the UK Nimal Senadheera owed an explanation as UK politicians seemed to be engaged in a stepped-up Sri Lanka bashing with the NPP government not making any effort to counter such propaganda against our country.

Interestingly, the UK government is on a collision course with no less a person than President Donald Trump over his recent humiliating comments on NATO troops who fought alongside the Americans in Afghanistan.

British Prime Minister Keir Starmer is on record as having said that President Trump’s comments were “insulting and frankly appalling.” Starmer suggested the US President apologise for his remarks. Amidst strong protests by humiliated NATO countries, President Trump retracted his derogatory comments.

But the UK’s position with regard to Tamil terrorism that also claimed the lives of nearly 1,500 Indian officers and men seemed different. The UK continues to ignore crimes perpetrated by the LTTE, including rival Tamil groups, political parties and Tamil civilians.

The Labour Party that promoted and encouraged terrorism throughout the war here raised the post-war Sri Lanka situation again.

The Labour Party questioned the British government in the House of Commons recently on what action it was taking to support Tamils seeking justice for past and ongoing abuses in Sri Lanka.

Raising the issue on 20 January 2026, Peter Lamb, the Labour MP for Crawley, asked: “What action is the UK Government taking to support Tamils in seeking justice for past and current injustices?”

Responding on behalf of the government, Hamish Falconer, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State at the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, said the UK remained actively engaged in accountability for crimes committed against the Tamil people.

“The UK is active in seeking justice and accountability for Sri Lanka’s Tamil community,” Falconer told the House. He said Britain continues to play a leading role at the United Nations Human Rights Council on resolutions addressing Sri Lanka’s human rights record.

Falconer added that the UK had taken concrete steps in recent years, including imposing sanctions. “Last year, we sanctioned Sri Lankans for human rights violations in the civil war,” he said, referring to measures targeting individuals implicated in serious abuses.

He also stated that the UK had communicated its expectations directly to Colombo. “We have made clear to the Sri Lankan Government the importance of improved human rights for all in Sri Lanka, as well as reconciliation,” Falconer said.

Concluding his response, Falconer marked the Tamil harvest festival, adding, “Let me take the opportunity to wish the Tamil community a happy Thai Pongal.”

The UK cannot be unaware that quite a number of ex-terrorists today carry British passports.

David Lammy’s promise

Our High Commissioner in London Nimal Senadheera, in consultation with the Foreign Ministry in Colombo, should take up the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State at the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office Hamish Falconer’s comment on sanctions imposed on Sri Lankans in March 2025. Falconer was referring to General (retd.) Shavendra Silva, Admiral of the Fleet Wasantha Karannagoda, General (retd), Jagath Jayasuriya and one-time LTTE commander Vinayagamoorthy Muralitharan, aka Karuna Amman.

The then Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs, David Lammy, declared in March 2025 that the above-mentioned Sri Lankans were sanctioned in line with election promises. A UK government statement quoted Lammy as having said: “I made a commitment during the election campaign to ensure those responsible are not allowed impunity. This decision ensures that those responsible for past human rights violations and abuses are held accountable.”

Since then David Lammy has received the appointment as Lord Chancellor, Secretary of State for Justice and Deputy Prime Minister.

Recent Thai Pongal celebrations held at 10 Downing Street for the second consecutive year, too, was used to disparage Sri Lanka with reference to genocide and Tamils fleeing the country. They have conveniently forgotten the origins of terrorism in Sri Lanka and how the UK, throughout the murderous campaign, backed terrorism by giving refuge to terrorists.

The British had no qualms in granting citizenship to Anton Balasingham, one-time translator at the British HC in Colombo and one of those who had direct access to LTTE leader Velupillai Prabhakaran. Balasingham’s second wife, Australian-born Adele, too, promoted terrorism and, after her husband’s demise in Dec 2006, she lives comfortably in the UK.

Adele had been captured in LTTE fatigues with LTTE women cadres. The possibility of her knowing the LTTE suicide attack on former Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in May 1991 can never be ruled out.

With the British PM accommodating those campaigning against Sri Lanka at 10 Downing Street and the Deputy PM openly playing politics with the issues at hand, Sri Lanka is definitely on a difficult wicket.

Sri Lanka has chosen to appease all at the expense of the war-winning military. The NPP government never made a genuine effort to convince Britain to rescind sanctions imposed on three senior ex-military officers and Karuna. The British found fault with Karuna because he switched allegiance to the Sri Lankan military in 2004. The former eastern commander’s unexpected move weakened the LTTE, not only in the eastern theatre of operations but in Vanni as well. Therefore, the British in a bid to placate voters of Sri Lankan origin, sanctioned Karuna while accommodating Adele whose murderous relationship with the LTTE is known both in and outside the UK Parliament.

Some British lawmakers, in a shameless and disgraceful manner, propagated lies in the UK Parliament for obvious reasons. Successive governments failed to counter British propaganda over the years but such despicable efforts, on behalf of the LTTE, largely went unanswered. Our governments lacked the political will to defend the war-winning armed forces. Instead, the treacherous UNP and the SLFP got together, in 2015, to back a US-led accountability resolution that sought to haul Sri Lanka up before the Geneva-based United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC).

The possibility of those who propagated lies receiving monetary benefits from interested parties cannot be ruled out. Sri Lanka never bothered to counter unsubstantiated allegations. Sri Lanka actually facilitated such contemptible projects by turning a blind eye to what was going on.

The Canadian Parliament declaration that Sri Lanka perpetrated genocide during the conflict didn’t surprise anyone. The 2022 May announcement underscored Sri Lanka’s pathetic failure on the ‘human rights’ front. The Gotabaya Rajapaksa government struggling to cope with the massive protest campaign (Aragalaya) never really addressed that issue. Ranil Wickremesinghe, who succeeded Gotabaya Rajapaksa in July 2022, too, failed to take it up with Canada. The NPP obviously has no interest in fighting back western lies.

The Canada Parliament is the first national body to condemn Sri Lanka over genocide. It wouldn’t be the only parliament to take such a drastic step unless Sri Lanka, at least now, makes a genuine effort to set the record straight. Political parties, representing our Parliament, never reached a consensus regarding the need to defeat terrorism in the North or in the South. Of those elected representatives backed terrorism in the North as well as terroirism in the South. Perhaps, they have collectively forgotten the JVP terrorism that targeted President JRJ and the entire UNP Parliamentary group. The JVP attack on the UNP, in parliament, in August 1987, is a reminder of a period of terror that may not have materialised if not for the Indian intervention.

By Shamindra Ferdinando

Midweek Review

Some heretical thoughts on educational reforms

The term education originates from the Latin words ‘educare’, meaning ‘to bring up’, and educere, meaning ‘to bring forth’. The precise definition of education is disputed. But if it is linked with the obvious expected outcome of it – learning, then the definition of education changes to a resultant outcome of ‘a change in behaviour’.

Let me say this at the outset. I am not going to get embroiled in the nitty-gritty pros and cons of the current controversies hogging the headlines today. Except to say this. As every discerning and informed person says, we need educational reforms. There is near unanimity on that. It is the process – a long, and even tedious process – that needs to be carried out that gives rise to disagreements and controversy. A public discussion, stakeholder viewpoints and expert opinion should be given due time and consideration.

Sex education – “the birds and bees” to start with – has to be gradually introduced into school curricular. When? is the critical question that needs specific answers. Do we need to go by Western standards and practices or by a deep understanding of our cultural milieu and civilisational norms? One thing is clear in my mind. Introduction of sex education into school curricular must not be used – or abused – to make it a ‘freeway’ for indiscriminate enforcement of the whole human sexual spectrum before the binary concepts of human sexuality has been clearly understood by children – especially during their pre-pubertal and immediate post-pubertal adolescent years. I have explicitly argued this issue extensively in an academic oration and in an article published in The Island, under the title, “The child is a person”.

Having said that, let me get on to some of my heretical thoughts.

Radical thinkers

Some radical thinkers are of the view that education, particularly collective education in a regulated and organised school system, is systematic streamlined indoctrination rather than fostering critical thinking. These disagreements impact how to identify, measure, and enhance various forms of education. Essentially, what they argue is that education channels children into pliant members of society by instilling existing or dominant socio-cultural values and norms and equipping them with the skills necessary to become ‘productive’ members of that given society. Productive, in the same sense of an efficient factory production line.

This concept was critiqued in detail by one of my favourite thinkers, Ivan Illych. Ivan Illich (1926 – 2002) was an Austrian philosopher known for his radical polemics arguing that the benefits of many modern technologies and social arrangements were illusory and that, still further, such developments undermined humans’ image of self-sufficiency, freedom, and dignity. Mass education and the modern medical establishment were two of his main targets, and he accused both of institutionalising and manipulating basic aspects of life.

One of his books that stormed into the bookshelves that retains particular relevance even today is the monumental heretical thought ‘Deschooling Society’ published in 1971 which became his best-known and most influential book. It was a polemic against what he called the “world-wide cargo cult” of government schooling. Illich articulated his highly radical ideas about schooling and education. Drawing on his historical and philosophical training as well as his years of experience as an educator, he presented schools as places where consumerism and obedience to authority were paramount. Illich had come to observe and experience state education during his time in Puerto Rico, as a form of “structured injustice.”

‘Meaningless credentials’

Ilych said that “genuine learning was replaced by a process of advancement through institutional hierarchies accompanied by the accumulation of largely meaningless credentials”. In place of compulsory mass schooling, Illich suggested, “it would be preferable to adopt a model of learning in which knowledge and skills were transmitted through networks of informal and voluntary relationships”. Talking of ‘meaningless credentials’ it has become the great cash-cow of the education industry the world over today – offering ‘honorary PhDs’ and ‘Dr’ titles almost over the counter. For a fee, of course. I wrote a facebook post titled “Its raining PhDs!”.

Mass education and the modern medical establishment were two of his main targets, and he accused both of institutionalising and manipulating basic aspects of life. I first got to ‘know’ of him through his more radical treatise “Medical Nemesis: The expropriation of Health”, that congealed many a thought that had traversed my mind chaotically without direction. He wrote that “The medical establishment has become a major threat to health. The disabling impact of professional control over medicine has reached the proportions of an iatrogenic epidemic”. But it was too radical a thought, far worse than ‘Deschooling Society’. The critics were many. But that is not our topic for the day.

The other more politically radical views on education comes from Paul Freire. Paul Freire (1921 – 1997) was a Brazilian educator and Marxist philosopher whose work revolutionised global thought on education. He is best known for his 1968 book “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” in which he reimagines teaching as a “collaborative act of liberation rather than transmission”. A founder of critical pedagogy, Freire’s influence spans literary movements, liberation theology, postcolonial education, Marxism, and contemporary theories of social justice and learning. He is widely regarded as one of the most important educational theorists of the twentieth century.

Neutral education process?

Richard Shaull, in his introduction to the 13th edition of ‘Pedagogy of the Oppressed’ wrote: “There is no such thing as a neutral education process. Education either functions as an instrument which is used to facilitate the integration of generations into the logic of the present system and bring about conformity to it, or it becomes the “practice of freedom”, the means by which men and women deal critically with reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their world”.

Here are a few quotes from Paul Freire before I revert to the topic I began to write on: “Liberating education consists in acts of cognition, not transferals of information.”; he believed that “true liberation comes from the oppressed taking agency and actively participating in the transformation of society”; he viewed “education as a political act for liberation – as the practice of freedom for the oppressed.”; He said that “traditional education is inherently oppressive because it serves the interests of the elite. It helps in the maintenance of the status quo.”

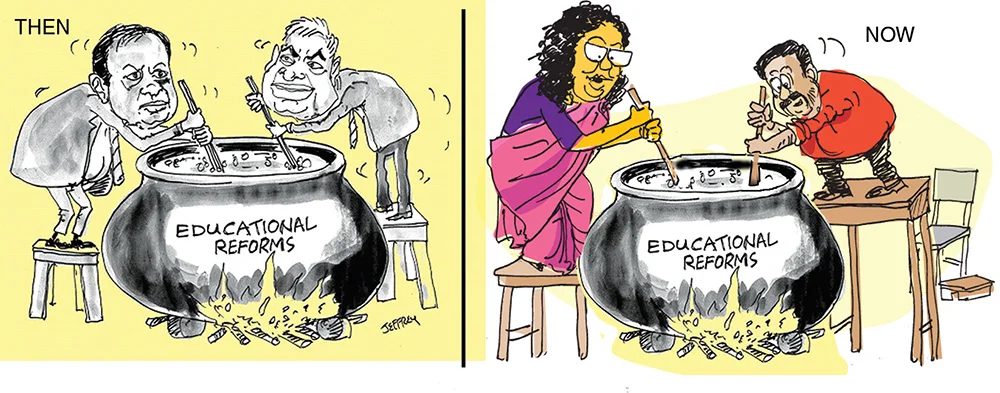

Where does our own ‘educational reforms’ stand? Is it transference, transformative, liberating or an attempt at maintaining the status quo with the help of the ADB? The history of educational reforms in Sri Lanka has been long. A quick check on the internet elicited the following:

Colonial Era (Pre-1940s): Colebrooke-Cameron Commission (1830s): Promoted English and standardised curriculum, laying groundwork for modern systems.

Buddhist Revival: Efforts by Anagarika Dharmapala to establish schools with Buddhist principles and English education.

The Kannangara Reforms (1940s): 1943 – Minister C.W.W. Kannangara introduced free education for all funded by general taxes; 1947 – introduced it from kindergarten to university. Central Schools (Madhya Maha Vidyalayas) established high-quality secondary schools in rural areas to ensure equitable access. Medium of Instruction was mandated to be the national languages (Sinhala and Tamil) for primary education.

Nationalisation and Standardisation

Nationalisation and Standardisation (1960s-1970s): 1961 – Denominational schools were taken over by the government to create a national education system. 1972 – New attempts at reform introduced following the 1971 youth uprising, focusing on democratising education and practical skills through a common curriculum and a national policy, responding to socio-economic needs. Introduction of language-based standardisation that in all likelihood triggered the ‘separatist war’. 1978 – change from language-based standardisation to district-based standardisation on a quota system for university entrance that was first introduced with a promise for only ten years, but persists until today, for nearly 50 years. No government dares to touch it as it is politically explosive.

Focus on quality and access (1980s-1990s): White Paper on Education (1981) – aimed to modernise the system together with components of privatising higher education. It faced severe criticism and public protests for its clear neoliberal leanings. And it never got off the ground. The National Colleges of Education (1986) were established.

1987 – Devolution of education power to provincial councils. 1991 – Establishment of The National Education Commission created to formulate long-term national policies. 1997 – Comprehensive reforms through a Presidential Task Force to overhaul the general education system (Grades 1-13), including early childhood development and special and adult education.

21st Century Reforms (2000s-Present): Mid-1990s-early 2000s – focused on transforming education from rote learning to competency-based, problem-solving skills; emphasising ICT, English, equity, and aligning education with labour market needs; introducing school restructuring (junior/senior schools) and compulsory education for ages 5-14; and aiming for national development through development of human capital.

Modernising education

2019 educational reforms focused on modernising education by shifting towards a modular, credit-based system with career pathways, reducing exam burdens, integrating vocational skills, and making education more equitable, though implementation details and debates around cultural alignment continued. Key changes included introducing soft skills and vocational streams from Grade 9/10; streamlining subjects, and ensuring every child completes 13 years of education; and moving away from an excessive focus on elite schools and competitive examinations.

This government is currently implementing the 2019 reforms in the National Education Policy Framework (2023–2033), which marks a radical departure from traditional methods. Module-Based System and a shift from exam-centric education to a module-based assessment system starting in 2026.

Already we have seen multi-pronged criticisms of these reforms. These mainly hinge on the inclusion – accidentally or intentionally – of a website for adult male friend groups. The CID is investigating whether it was sabotage.

Restricting access to social media

When there is a global concern on the use of smartphones and internet by children, and where Australia has already implemented a new law in December 2025 banning under-16s from major social media platforms to protect children from cyberbullying, grooming, and addiction, requiring tech companies to use age verification.

The U.S. does not have a federal law banning smartphones for under-16s, but a major movement, fuelled by the US Surgeon-General warnings and research on youth mental health, is pushing for restrictions, leading many individual states (like California, Florida, Virginia) to enact laws or guidelines for school-day bans or limits for students, focusing on classroom distraction and social media risks, with some advocates pushing for no smartphones before high school or age 16.

The UK doesn’t currently have a legal ban on smartphones for under-16s, but there’s significant political and public pressure for restrictions, with debates focusing on social media access and potential school bans, with some politicians and experts advocating bans similar to Australia’s, while others push for stronger regulations under the existing Online Safety Act to protect children from addictive algorithms and harm.

Sweden is implementing a nationwide ban on mobile phones in schools for students aged 7 to 16, starting in autumn 2026, requiring devices to be handed in until the school day ends to improve focus, security, and academic performance, as part of a major education reform. This national law, not just a recommendation, aims to reduce distractions and promote traditional learning methods like books and physical activity, addressing concerns about excessive screen time affecting children’s health and development.

Norway doesn’t have a complete smartphone ban for under-16s but is moving to raise the minimum age for social media access to 15 and has implemented strong recommendations, including a ban on phones in schools to protect children from harmful content and digital overexposure, with studies showing positive impacts on focus and well-being. The government aims to shield kids from online harms like abuse and exploitation, working with the EU to develop age verification for platforms like TikTok and Instagram.

Finland implemented a law in August 2025 restricting smartphone use for students aged 7-16 during the school day, empowering teachers to ban devices in classrooms, meals, and breaks, except for educational or health reasons, to combat distractions, improve focus, and support student well-being and social skills. The move aims to create calmer learning environments, reduce cyberbullying, and encourage more in-person interaction, giving teachers control to confiscate disruptive phones, though digital tools remain part of education.

Trend in liberal west

When this is the trend in the ‘liberal West’ on the use of smartphones by children in schools, did not our educational reform initiators, experts and pundits in the NIE not been observing and following these worldwide trends? How could they recommend grade 6 children to go to (even a harmless legitimate) website? Have they been in hibernation when such ‘friend/chat room’ sites have been the haunt of predatory paedophile adults? Where have they been while all this has been developing for the past decade or more? Who suggested the idea of children being initiated into internet friends chat rooms through websites? I think this is not only an irresponsible act, but a criminal one.

Even if children are given guided, supervised access to the internet in a school environment, what about access to rural children? What about equity on this issue? Are nationwide institutional and structural facilities available in all secondary schools before children are initiated into using the internet and websites? What kind of supervision of such activities have been put in place at school (at least) to ensure that children are safe from the evils of chat rooms and becoming innocent victims of paedophiles?

We are told that the new modular systems to be initiated will shift assessments from an exam-centric model to a modular-based, continuous assessment system designed to prioritise skill development, reduce stress, and promote active learning. The new reforms, supposed to begin in 2026, will introduce smaller, self-contained learning modules (covering specific topics or themes) with integrated, ongoing assessments.

Modular assessment and favouritism

I will not go into these modular assessments in schools in any detail. Favouritism in schools is a well-known problem already. 30% of final assessments to be entrusted to the class teacher is a treacherous minefield tempting teachers into corrupt practices. The stories emanating from the best of schools are too many to retell. Having intimate knowledge of what happens to student assignment assessments in universities, what could happen in schools is, to me, unimaginable. Where do the NIE experts live? In Sri Lanka? Or are they living in ideal and isolated ivory towers? Our country is teeming with corruption at every level. Are teachers and principals immune from it? Recently, I saw a news item when a reputed alumnus of “the best school of all” wrote a letter to the President citing rampant financial corruption in the school.

This article is already too long. So, before I wind up, let me get on to a conspiracy theory. Why have the World Bank and the ADB been pumping millions of USD into ‘improving’ our education system?

World Bank

The World Bank is the largest source of external financing for education in developing countries, maintaining an active portfolio of approximately $26 billion in 94 countries reaching an estimated 425 million students— roughly one-third of all students in low- and middle-income countries.

The World Bank funds education globally through loans, grants, and technical assistance to improve access, quality, and equity, focusing on areas like teacher training, digital infrastructure, and learning outcomes, with significant recent investment in Fragile, Conflict, and Violence (FCV) settings and pandemic recovery efforts. Funding supports national education strategies, like modernising systems in Sri Lanka, and tackles specific challenges such as learning loss, with approaches including results-based financing and supporting resilient systems. Note this phrase – ” … with significant recent investment in Fragile, Conflict, and Violence (FCV) settings ….”. The funds are monumental for FCV Settings – $7 billion invested in Fragile, Conflict, and Violence settings, with plans for $1.2 billion more in 2024-25. Now with our Ditwah disaster, it is highly fertile ground for their FCV investments.

Read Naomi Kline’s epic “The Shock Doctrine: The rise of disaster capitalism”. It tells it all. It must be read and digested to understand the psychology of funding for FCV settings.

The 40.3 million USD World Bank’s IRQUE (Improving Relevance and Quality of Undergraduate Education) Project in Sri Lanka (circa 2003-2009) was a key initiative to modernize the country’s higher education by boosting quality, accountability, and relevance to the job market, introducing competitive funding (QEF), establishing Quality Assurance (QA) functions for the first time, and increasing market-oriented skills, significantly reducing graduate unemployment. I was intimately involved in that project as both Dean/Medicine and then VC of University of Ruhuna. Again, the keywords ‘relevance to the job market’ comes to mind.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) is heavily funding education reform in Sri Lanka, notably with a significant $400 million loan (Secondary Education Sector Improvement Program – SESIP) to transform secondary education, aligning it with global knowledge economy demands, improving curriculum, teacher training, and infrastructure for quality access. ADB also provides ongoing support, emphasising teacher training, digital tech, and infrastructure, viewing Sri Lanka’s youth and education as crucial for development. The keywords are ‘aligning it with global knowledge economy demands’. As of 2019, ADB loans for education totalled approximately $1.1 billion, with cumulative funding for pre-primary, primary, and secondary education exceeding $7.4 billion since 1970 in the Asia-Pacific region.

Radical view of IMF and WB

A radical view of the Bretton Woods twins – the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank – and the ADB characterises them not as neutral facilitators of global economic stability and egalitarian economic development in poor countries, but as tools of Western hegemony, neoliberal imposition, and institutionalized inequality. From this perspective, these institutions, created to manage the post-WWII economic order, have evolved into instruments that perpetuate the dominance of the Global North over the Global South.

The World Bank and the ADB (in our part of the world) have been investing heavily on education reform in poor countries in Asia and Africa. Why? Surely, they are not ‘charity organisations’? What returns are they expecting for their investments? Let me make a wild guess. The long-term objective of WB/ADB is to have ‘employable graduates in the global job market’. A pliant skilled workforce for exploitation of their labour. Not for “education as a political act for liberation” as Paul Freire put it.

I need to wind up my heretical thoughts on educational reform. For those of us who wish to believe that the WB and ADB is there to save us from illiteracy, poverty and oppression, I say, dream on.

“Don’t let schooling interfere with your education. Education consists mainly of what we have unlearned.” – Mark Twain

by Susirith Mendis

Susmend2610@gmail.com

Midweek Review

A View from the Top

They are on a leisurely uphill crawl,

These shiny, cumbrous city cars,

Beholding in goggle-eyed wonder,

Snow gathering on mountain tops,

Imagining a once-in-a-lifetime photo-op,

But the battered land lying outside,

Gives the bigger picture for the noting eye,

Of wattle-and-daub hut denizens,

Keeping down slowly rising anger,

On being deprived the promised morsel.

By Lynn Ockersz

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoComBank, UnionPay launch SplendorPlus Card for travelers to China

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoClimate risks, poverty, and recovery financing in focus at CEPA policy panel

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoSri Lanka, the Stars,and statesmen

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoHayleys Mobility ushering in a new era of premium sustainable mobility

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days agoLuck knocks at your door every day

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoAdvice Lab unveils new 13,000+ sqft office, marking major expansion in financial services BPO to Australia

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoArpico NextGen Mattress gains recognition for innovation

-

Editorial2 days ago

Editorial2 days agoGovt. provoking TUs