Features

Capturing wild beauty of Lanka:An exquisite photographic guide

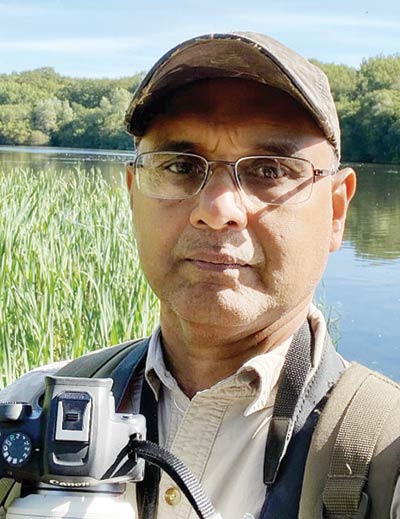

Ifham Nizam interviews Gehan de Silva Wijeyeratne, lead author and photographer of ‘A Photographic Guide to the Wildlife of Sri Lanka’ published by John Beaufoy Publishing.

Q: What first inspired your interest in natural history and biodiversity, particularly in Sri Lanka?

A:From the age of three, I was on Leopard Safari with my uncle Dodwell de Silva in Wilpattu and Yala. He was also a birdwatcher and used to bring with him a copy of G. M. Henry’s ‘A Guide to the Birds of Ceylon’ which was first published in 1955. I learnt from him to identify birds and to put a name to them. When I was around thirteen years old, I began to roam around Colombo with my neighbour Azly Nazeem and his classmate Jeevan William. I realised that some of the birds I knew from Yala and Wilpattu such as the Red-wattled Lapwing and the Indian Roller could be seen even in Colombo. It dawned on me I did not have to wait for trips out of Colombo to enjoy wildlife.

My parents Laskhmi and Dalton encouraged my interest in wildlife and used to give me wildlife books as presents for my birthday and Christmas. Sri Lanka in the 1970s and early 1980s was a poor country and even then I realised that I was in a privileged position to receive books like this. Most of the books had been published abroad and I read about rainforests. Thilo Hoffmann with the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society published a booklet about the need to save Sinharaja Rainforest from being logged. I was gobsmacked to learn that Sri Lanka had rainforests. Back then none of my friends and family believed me when I said that Sri Lanka has rainforests.

I was probably the only person in the whole school amongst students and teachers who had woken up to this. It shows the lack of awareness then. Everyone thought rainforests were something found in the Amazon. When I was fifteen with a handful of friends including Jeevan William, Lester Perera and Senaka Jayasuriya we trekked across Sinharaja. The Forest Department insisted we brought letters of permission from the school and parents.

They had at that time never had any school children wanting to trek across Sinharaja. By now I had realised that I had a deep love to learn about the wildlife around me in Colombo and in Sri Lanka. I began to attend meetings of the WNPS, March for Conservation (MFC), Field Ornithology Group of Sri Lanka (FOGSL) and the Sri Lanka Natural History Society (SLNHS) and began to learn a lot from a bunch of inspirational people. The learning continues today.

Q: About your transition from a career in finance to becoming one of Sri Lanka’s leading naturalists?

A: There are many people who deserve the credit for this. Everything I know is what I learnt from someone else. The foundation was laid by my uncle Dodwell getting me interested and my parents and siblings who supported me. The friends and organisations I mentioned earlier allowed me to go into the field and join a group of people who could nurture my interest. The involvement of some people is not so obvious, but they played a key role.

Mr. Lokanathan the scout master in school realised I had potential and put me into leadership roles so that I could develop my self-confidence, people skills and be confident leading small field expeditions. George Ondaatje, an Advanced Level Physics teacher, taught me how to think critically. I went over to London to study Civil Engineering. I then qualified as a Chartered Accountant and then began to spend every week-end on field meetings organised by the London Natural History Society (LNHS) and the London Wildlife Trust (LWT) and local groups of the RSPB.

I did not realise it then but I was honing my skills as a naturalist and photographer and my city job was training me to look at things through a business lens. In 1996, I approached the Oriental Bird Club to ask if they would like to do a feature on the wildlife art of Lester Perera.

They made a counter offer. They would publish his art to illustrate ‘A Birdwatcher’s Guide to Sri Lanka’ if I could write in to complement what they had already published on India, Malaysia and Indonesia. I lead-authored this and the Sri Lanka Tourism industry were pleasantly surprised to learn that someone working in the financial sector in London was publicising Sri Lanka as a bird watching destination. I began to engage with people in Sri Lankan tourism.

The scene was set. I had by now acquired a fairly well-rounded set of skills to publicise Sri Lanka as a wildlife destination. But it needed two people to set things in motion. Firstly, my wife Nirma decided that after the birth of our first daughter Maya that we will return to Sri Lanka so that grandparents and grandchildren will have time together. I was not pleased. I was happy in London and my career was on a good trajectory.

But Nirma spoke to various people in Colombo and lined up job interviews and I found myself being a part of the management team set up to launch Nations Trust Bank. The next big step came when Hiran Cooray came home for dinner and suggested that I join Jetwing to set up a wildlife travel company as well as to develop the wildlife tourism potential of Jetwing Hotels. I agreed on the condition that I could implement some of the activities undertaken by UK conservation NGOs through the private sector, as we could integrate support for research and conservation into a business model.

So much to the surprise and initial dismay of many of the Jetwing senior team I joined Jetwing. They wondered what someone from the UK financial services industry could bring to one of the largest tourism companies. They wondered if it had been a mistake to bring me in and when I started talking about how Sri Lanka could become a big game safari destination for animals like Leopards, they were convinced I was a mad hatter.

They were incredulous. Leopards? Many of the senior team had been in tourism for about 25 years each and no one had mentioned leopards as a tourism product. Surely Hiran would now realise this was all a terrible mistake and send the mad man back to London to work in the city. Anyway, it’s another story, but the team at Jetwing soon realised that I had something useful to add and it was totally embraced. Before long, the sceptics became my allies. They remain as good friends to this day. Ifham, you were one of the first in the media to realise that I was a new voice in tourism and I believe you did the first press interview of me.

Q: Could you share the inspiration behind your latest book? What new elements or approaches did you introduce in this book?

A: In the early 2000s, I began a series of photographic leaflets and booklets with Jetwing Eco Holidays so that a wide range of people could have affordable literature to identify birds, mammals, butterflies, dragonflies etc. Some of these were sold for as little as one hundred rupees and made a huge impact as before the identification books available were very expensive, rare books and out of the reach of many people.

Publishers such as New Holland and John Beaufoy Publishing allowed me to develop the publications a stage further by commissioning me to produce affordable and portable photographic guides. These were important stepping stones.

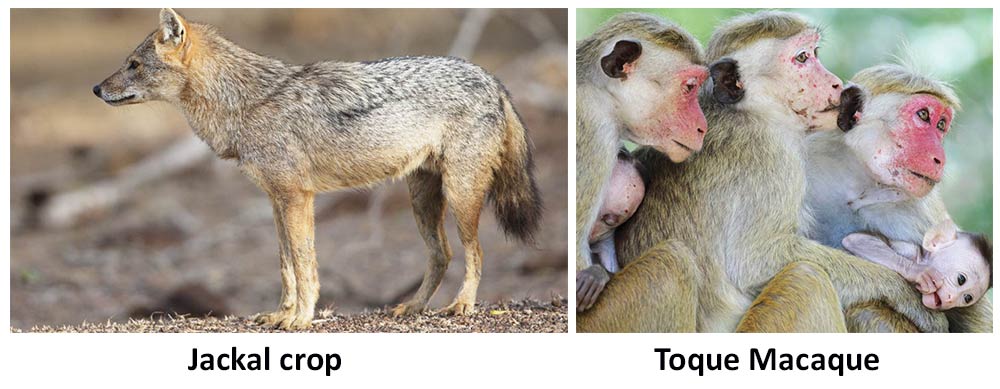

Having seen photographic guides to multiple taxonomic groups it was always on the back of my mind to develop one for Sri Lanka. This book is not the first of this genre for Sri Lanka. FOGSL published books about the Talangama Wetland and Uda Walawe National Park, which were on this multi-taxonomic group theme. However, this book is the first in Sri Lanka to cover the popular taxonomic groups in good enough detail for field use when travelling around Sri Lanka. A key element in this book is that I invited 13 other section contributors to accelerate the publication timetable for this book. If I had tried to do it all by myself, we would still be waiting.

Q: How did you choose other authors featured in the book? Were there any that you found particularly challenging or rewarding to document?

A:I was aware of the work being done by others so it was easy for me to reach out to other authors who I knew had field experience and good images for writing sections that would be of interest to a natural history audience. There are a lot more people I could have brought in, and a lot more material I would have liked to have added. But the publisher did not want it become too big and expensive, an important consideration.

Q: Sri Lanka is known for its rich biodiversity. Could you discuss any conservation efforts you believe are crucial right now?

Firstly, we have to hold onto what we already have, these include what we know as Other State Forests. Secondly, we have to rehabilitate and restore damaged areas. Thirdly, we need to see how we can construct corridors for wildlife to move in-between forest patches. A useful idea put forward by Rohan Pethiyagoda is to re-wild the reservations beside our 105 river systems. We could also look at re-wilding a narrow belt beside our main roads and railways, where practicable.

We should also encourage landowners to make space for nature. This is not just the owners of big properties such as tourist hotels and factories to re-wild a part of their grounds. But even individual home owners can plant trees and shrubs which are friendly to native wildlife. In our city parks, we should plant groves of native dipterocarps so that people can understand what our land looked like a few hundred years ago.

Q: Are there any particular species or habitats in Sri Lanka that you feel are underappreciated or misunderstood by the public?

A: It’s a sad reality that very few Sri Lankans have had the opportunity to appreciate the wonder of a lowland rainforest. Even if they visited one, we don’t have enough trained people or the visitor education resources to do justice to what we have.

Until recently, wetlands were also under-appreciated. But with the beautification of Colombo and the actions of government agencies wetlands such as Diyasaru Wetland Park (Sri Lanka Land Reclamation and Development Corporation) and Beddegana Wetland Park (Urban Development Authority) are now being visited by many people for recreational activity as well as wildlife watching. Making it easy to use these sites for wedding shoots have been a game changer as not only do they bring in a lot of people they generate significant revenues to pay for their upkeep.

Q: What do you hope this book will achieve?

A: I hope it becomes the standard book which people will take with them into the field whether it is as a wildlife enthusiast or professional naturalist. I hope wildlife enthusiasts will start to widen the scope of what they look at. For professional naturalist guides I hope this book becomes a powerful tool which will help Sri Lanka to monetise its wildlife. When the country’s wildlife is aligned to its economic agenda, it becomes easier to make a case to conserve the country’s remaining wild spaces and the species within them. Unfortunately, this book won’t be within the reach of many people who work in wildlife and tourism. Therefore, in the book I have put in an appeal for foreign tourists to consider giving away their used copy to local people who may benefit from having it.

(To be continued)

Features

RIDDHI-MA:

A new Era of Dance in Sri Lanka

Kapila Palihawadana, an internationally renowned dancer and choreographer staged his new dance production, Riddhi-Ma, on 28 March 2025 at the Elphinstone theatre, which was filled with Sri Lankan theatregoers, foreign diplomats and students of dance. Kapila appeared on stage with his charismatic persona signifying the performance to be unravelled on stage. I was anxiously waiting to see nATANDA dancers. He briefly introduced the narrative and the thematic background to the production to be witnessed. According to him, Kapila has been inspired by the Sri Lankan southern traditional dance (Low Country) and the mythologies related to Riddhi Yâgaya (Riddi Ritual) and the black magic to produce a ‘contemporary ballet’.

Riddhi Yâgaya also known as Rata Yakuma is one of the elaborative exorcism rituals performed in the southern dance tradition in Sri Lanka. It is particularly performed in Matara and Bentara areas where this ritual is performed in order to curb the barrenness and the expectation of fertility for young women (Fargnoli & Seneviratne 2021). Kapila’s contemporary ballet production had intermingled both character, Riddi Bisaw (Princes Riddhi) and the story of Kalu Kumaraya (Black Prince), who possesses young women and caught in the evil gaze (yaksa disti) while cursing upon them to be ill (De Munck, 1990).

Kapila weaves a tapestry of ritual dance elements with the ballet movements to create visually stunning images on stage. Over one and a half hours of duration, Kapila’s dancers mesmerized the audience through their virtuosic bodily competencies in Western ballet, Sri Lankan dance, especially the symbolic elements of low country dance and the spontaneity of movements. It is human bodily virtuosity and the rhythmic structures, which galvanised our senses throughout the performance. From very low phases of bodily movements to high speed acceleration, Kapila managed to visualise the human body as an elevated sublimity.

Contemporary Ballet

Figure 2 – (L) Umesha Kapilarathna performs en pointe, and (R) Narmada Nekethani performs with Jeewaka Randeepa, Riddhi-Ma, at Elphinstone Theatre, Maradana, 28th March 2025. Source:

Malshan Witharana

The dance production Riddhi-Ma was choreographed in several segments accompanied by a flow of various music arrangements and sound elements within which the dance narrative was laid through. In other words, Kapila as a choreographer, overcomes the modernist deadlock in his contemporary dance work that the majority of Sri Lankan dance choreographers have very often succumbed to. These images of bodies of female dancers commensurate the narrative of women’s fate and her vulnerability in being possessed by the Black Demon and how she overcomes and emancipates from the oppression. In this sense, Kapila’s dancers have showcased their ability to use the bodies not much as an object which is trained to perform a particular tradition but to present bodily fluidity which can be transformed into any form. Kapila’s performers possess formlessness, fluid fragility through which they break and overcome their bodily regimentations.

It was such a highly sophisticated ‘contemporary ballet’ performed at a Sri Lankan theatre with utmost rigour and precision. Bodies of all male and female dancers were highly trained and refined through classical ballet and contemporary dance. In addition, they demonstrated their abilities in performing other forms of dance. Their bodies were trained to achieve skilful execution of complex ballet movements, especially key elements of traditional ballet namely, improvisation, partnering, interpretation and off-balance and the local dance repertoires. Yet, these key ballet elements are not necessarily a part of contemporary ballet training (Marttinen, 2016). However, it is important for the dance students to learn these key elements of traditional ballet and use them in the contemporary dance settings. In this sense, Kapila’s dancers have achieved such vigour and somatic precision through assiduous practice of the body to create the magic on stage.

Pas de deux

Among others, a particular dance sequence attracted my attention the most. In the traditional ballet lexicon, it is a ‘pas de deux’ which is performed by the ‘same race male and female dancers,’ which can be called ‘a duet’. As Lutts argues, ‘Many contemporary choreographers are challenging social structures and norms within ballet by messing with the structure of the pas de deux (Lutts, 2019). Pas de Deux is a dance typically done by male and female dancers. In this case, Kapila has selected a male and a female dancer whose gender hierarchies appeared to be diminished through the choreographic work. In the traditional pas de deux, the male appears as the backdrop of the female dancer or the main anchorage of the female body, where the female body is presented with the support of the male body. Kapila has consciously been able to change this hierarchical division between the traditional ballet and the contemporary dance by presenting the female dominance in the act of dance.

The sequence was choreographed around a powerful depiction of the possession of the Gara Yakâ over a young woman, whose vulnerability and the powerful resurrection from the possession was performed by two young dancers. The female dancer, a ballerina, was in a leotard and a tight while wearing a pair of pointe shoes (toe shoes). Pointe shoes help the dancers to swirl on one spot (fouettés), on the pointed toes of one leg, which is the indication of the ballet dancer’s ability to perform en pointe (The Kennedy Centre 2020).

The stunning imagery was created throughout this sequence by the female and the male dancers intertwining their flexible bodies upon each other, throwing their bodies vertically and horizontally while maintaining balance and imbalance together. The ballerina’s right leg is bent and her toes are directed towards the floor while performing the en pointe with her ankle. Throughout the sequence she holds the Gara Yakâ mask while performing with the partner.

The male dancer behind the ballerina maintains a posture while depicting low country hand gestures combining and blurring the boundaries between Sri Lankan dance and the Western ballet (see figure 3). In this sequence, the male dancer maintains the balance of the body while lifting the female dancer’s body in the air signifying some classical elements of ballet.

Haptic sense

Figure 3: Narmada Nekathani performs with the Gara Yaka mask while indicating her right leg as en pointe. Male dancer, Jeewaka Randeepa’s hand gestures signify the low country pose. Riddhi-Ma, Dance Theatre at Elphinstone Theatre, 28th March 2025. Source: Malshan Witharana.

One significant element of this contemporary ballet production is the costume design. The selection of colour palette, containing black, red and while combining with other corresponding colours and also the costumes which break the traditional rules and norms are compelling. I have discussed in a recent publication how clothes connect with the performer’s body and operate as an embodied haptic perception to connect with the spectators (Liyanage, 2025). In this production, the costumes operate in two different ways: First it signifies sculpted bodies creating an embodied, empathic experience.

Secondly, designs of costumes work as a mode of three dimensional haptic sense. Kapila gives his dancers fully covered clothing, while they generate classical ballet and Sinhalese ritual dance movements. The covered bodies create another dimension to clothing over bodies. In doing so, Kapila attempts to create sculpted bodies on stage by blurring the boundaries of gender oriented clothing and its usage in Sri Lankan dance.

Sri Lankan female body on stage, particularly in dance has been presented as an object of male desire. I have elsewhere cited that the lâsya or the feminine gestures of the dance repertoire has been the marker of the quality of dance against the tândava tradition (Liyanage, 2025). The theatregoers visit the theatre to appreciate the lâsya bodies of female dancers and if the dancer meets this threshold, then she becomes the versatile dancer. Kandyan dancers such as Vajira and Chithrasena’s dance works are explored and analysed with this lâsya and tândava criteria. Vajira for instance becomes the icon of the lâsya in the Kandyan tradition. It is not my intention here to further discuss the discourse of lâsya and tândava here.

But Kapila’s contemporary ballet overcomes this duality of male-female aesthetic categorization of lâsya and tândava which has been a historical categorization of dance bodies in Sri Lanka (Sanjeewa 2021).

Figure 4: Riddhi-Ma’s costumes creates sculpted bodies combining the performer and the audience through empathic projection. Dancers, Sithija Sithimina and Senuri Nimsara appear in Riddhi-Ma, at Elphinstone Theatre, 28th March 2025, Source, Malshan Witharana.

Conclusion

Dance imagination in the Sri Lankan creative industry exploits the female body as an object. The colonial mind set of the dance body as a histrionic, gendered, exotic and aesthetic object is still embedded in the majority of dance productions produced in the current cultural industry. Moreover, dance is still understood as a ‘language’ similar to music where the narratives are shared in symbolic movements. Yet, Kapila has shown us that dance exists beyond language or lingual structures where it creates humans to experience alternative existence and expression. In this sense, dance is intrinsically a mode of ‘being’, a kinaesthetic connection where its phenomenality operates beyond the rationality of our daily life.

At this juncture, Kapila and his dance ensemble have marked a significant milestone by eradicating the archetypical and stereotypes in Sri Lankan dance. Kapila’s intervention with Riddi Ma is way ahead of our contemporary reality of Sri Lankan dance which will undoubtedly lead to a new era of dance theatre in Sri Lanka.

References

De Munck, V. C. (1990). Choosing metaphor. A case study of Sri Lankan exorcism. Anthropos, 317-328. Fargnoli, A., & Seneviratne, D. (2021). Exploring Rata Yakuma: Weaving dance/movement therapy and a

Sri Lankan healing ritual. Creative Arts in Education and Therapy (CAET), 230-244.

Liyanage, S. 2025. “Arts and Culture in the Post-War Sri Lanka: Body as Protest in Post-Political Aragalaya (Porattam).” In Reflections on the Continuing Crises of Post-War Sri Lanka, edited by Gamini Keerawella and Amal Jayawardane, 245–78. Colombo: Institute for International Studies (IIS) Sri Lanka.

Lutts, A. (2019). Storytelling in Contemporary Ballet.

Samarasinghe, S. G. (1977). A Methodology for the Collection of the Sinhala Ritual. Asian Folklore Studies, 105-130.

Sanjeewa, W. (2021). Historical Perspective of Gender Typed Participation in the Performing Arts in Sri Lanka During the Pre-Colonial, The Colonial Era, and the Post-Colonial Eras. International Journal of Social Science And Human Research, 4(5), 989-997.

The Kennedy Centre. 2020. “Pointe Shoes Dancing on the Tips of the Toes.” Kennedy-Center.org. 2020 https://www.kennedy-center.org/education/resources-for-educators/classroom-resources/media- and-interactives/media/dance/pointe-shoes/..

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Himansi Dehigama for proofreading this article.

About the author:

Saumya Liyanage (PhD) is a film and theatre actor and professor in drama and theatre, currently working at the Department of Theatre Ballet and Modern Dance, Faculty of Dance and Drama, University of the Visual and Performing Arts (UVPA), Colombo. He is the former Dean of the Faculty of Graduate Studies and is currently holding the director position of the Social Reconciliation Centre, UVPA Colombo.

Features

Sri Lanka’s Foreign Policy amid Geopolitical Transformations: 1990-2024 – Part II

Chinese Naval Entry and End of Post-War Unipolarity

The ascendancy of China as an emerging superpower is one of the most striking shifts in the global distribution of economic and political power in the 21st century. With its strategic rise, China has assumed a more proactive diplomatic and economic role in the Indian Ocean, signalling its emergence as a global superpower. This new leadership role is exemplified by initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). The Economist noted that “China’s decision to fund a new multilateral bank rather than give more to existing ones reflects its exasperation with the glacial pace of global economic governance reform” (The Economist, 11 November 2014). Thus far, China’s ascent to global superpower status has been largely peaceful.

In 2025, in terms of Navy fleet strength, China became the world’s largest Navy, with a fleet of 754 ships, thanks to its ambitious naval modernisation programme. In May 2024, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) further strengthened its capabilities by commissioning the Fujian, its latest aircraft carrier. Equipped with an advanced electromagnetic catapult system, the Fujian can launch larger and heavier aircraft, marking a significant upgrade over its predecessors.

Driven by export-led growth, China sought to reinvest its trade surplus, redefining the Indian Ocean region not just as a market but as a key hub for infrastructure investment. Notably, over 80 percent of China’s oil imports from the Persian Gulf transit to the Straits of Malacca before reaching its industrial centres. These factors underscore the Indian Ocean’s critical role in China’s economic and naval strategic trajectories.

China’s port construction projects along the Indian Ocean littoral, often associated with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), exemplify its deepening geopolitical and economic engagement in the region. These initiatives encompass multipurpose berth development, deep-sea port construction, and supporting infrastructure projects aimed at enhancing maritime connectivity and trade. Key projects include the development of Gwadar Port in Pakistan, a strategic asset for China’s access to the Arabian Sea; Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka, which became a focal point of debt diplomacy concerns; the Payra deep-sea port in Bangladesh; as well as port and road infrastructure development in Myanmar’s Yunnan and Kyaukphyu regions and Cambodia’s Koh Kong.

While these projects were promoted as avenues for economic growth and regional connectivity, they also triggered geopolitical tensions and domestic opposition in several host countries. Concerns over excessive debt burdens, lack of transparency, and potential dual-use (civilian and military) implications of port facilities led to scrutiny from both local and external stakeholders, including India and Western powers. As a result, some projects faced significant pushback, delays, and, in certain cases, suspension or cancellation. This opposition underscores the complex interplay between economic cooperation, strategic interests, and sovereignty concerns in China’s Indian Ocean engagements.

China’s expanding economic, diplomatic, and naval footprint in the Indian Ocean has fundamentally altered the region’s strategic landscape, signalling the end of early post-Cold War unipolarity. Through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) initiatives, China has entrenched itself economically, financing. Diplomatically, Beijing has deepened its engagement with littoral states through bilateral agreements, security partnerships, and regional forums, challenging traditional Western and Indian influence.

China’s expanding naval deployments in the Indian Ocean, including its military base in Djibouti, and growing security cooperation with regional states, mark the end of unchallenged US dominance in the region. The Indian Ocean is now a contested space, where China’s presence compels strategic recalibrations by India, the United States, and other regional actors. The evolving security landscape in the Indian Ocean—marked by intensifying competition, shifting alliances, and the rise of a multipolar order—has significant implications for Sri Lanka’s geopolitical future.

India views China’s growing economic, political, and strategic presence in the Indian Ocean region as a key strategic challenge. In response, India has pursued a range of strategic, political, and economic measures to counterbalance Chinese influence, particularly in countries like Sri Lanka through infrastructure investment, defense partnerships, and diplomatic engagements.

Other Extra-Regional powers

Japan and Australia have emerged as significant players in the post-Cold War strategic landscape of the Indian Ocean. During the early phases of the Cold War, Australia played a crucial role in Western ‘Collective Security Alliances’ (ANZUS and (SEATO). However, its direct engagement in Indian Ocean security remained limited, primarily supporting the British Royal Navy under Commonwealth obligations. Japan, meanwhile, refrained from deploying naval forces in the region after World War II, adhering to its pacifist constitution and post-war security policies. In recent decades, shifting strategic conditions have prompted both Japan and Australia to reassess their roles in the Indian Ocean, leading to greater defence cooperation and a more proactive regional presence.

In the post-Cold War era, Australia has progressively expanded its naval engagements in the Indian Ocean, driven by concerns over maritime security, protection of trade routes, and China’s growing influence. Through initiatives, such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) and deeper defence partnerships with India and the United States, Australia has bolstered its strategic presence in the Indian Ocean region.

Recalibration of Japan’s approach

Japan, too, has recalibrated its approach to Indian Ocean security in response to geopolitical shifts. Recognising the Indian Ocean’s critical importance for its energy security and trade, Japan has strengthened its naval presence through port visits, joint exercises, and maritime security cooperation. The Japan Maritime Self-Defence Force (JMSDF) has taken on a more active role in anti-piracy operations, freedom of navigation operations (FONOPS), and strategic partnerships with Indian Ocean littoral states. This shift aligns with Japan’s broader strategy of contributing to regional stability while balancing its constitutional constraints on military force projection.

Japan’s proactive role in the Indian Ocean region is evident in its diplomatic and defence engagements. In January 2019, Japan sent its Foreign Minister, Taro Kono, and Chief of Staff, Joint Staff, Katsutoshi Kawano, to the Raisina Dialogue, a high-profile geopolitical conference in India. Japan’s National Security Strategy, released in December 2022, identifies China’s growing assertiveness as its greatest strategic challenge and underscores the need to deepen bilateral ties and multilateral defence cooperation in the Indian Ocean. It also emphasises the importance of securing stable access to sea-lanes, through which more than 80 percent of Japan’s oil imports pass. In recent years, Japan has expanded its port investment portfolio across the Indian Ocean, with major projects in Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Myanmar. In 2021, Japan participated for the first time in CARAT-Sri Lanka (Cooperation Afloat Readiness and Training), a bilateral naval exercise. Japan’s Maritime Self-Defence Force returned for the exercise in January 2023, held at Trincomalee Port and Mullikulam Base.

Japan’s strategic interests in the Indian Ocean have been most evident in its involvement in port infrastructure development projects. Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Myanmar are key countries where early Chinese-led port construction faced setbacks. Unlike India, which carries historical and political complexities in its relations with these countries, Japan is better positioned to compete with China. In December 2021, a Japanese company established a ship repair and rebuilding facility in Trincomalee, complementing the already well-established Tokyo Cement factory. When the Sri Lanka Ports Authority announced plans in mid-2022 to develop Trincomalee as an industrial port—inviting expressions of interest from investors to utilise port facilities and up to 2,400 hectares of surrounding land—Trincomalee regained strategic attention.

The Colombo Dockyard, in collaboration with Japan’s Onomichi Dockyard, has established a rapid response afloat service in Trincomalee, marking a significant development in Japan’s engagement with Sri Lanka’s maritime infrastructure. This initiative aligns with Japan’s broader strategic interests in the Bay of Bengal, a region of critical economic and security importance. A key Japanese concern appears to be limiting China’s ability to establish a permanent presence in Trincomalee. This initiative underscores the broader strategic competition in the Indian Ocean. Trincomalee, with its deep-water harbour, has long been regarded as a critical maritime asset. Japan’s involvement reflects its efforts to deepen economic and strategic engagement with Sri Lanka amid growing regional competition. The challenge before Sri Lanka is how to navigate this strategic contest while maximising its national interests.

Other Regional Powers

In analyzing the evolving naval security architecture of the post-Cold War Indian Ocean, particular attention should be given to the naval developments of regional powers such as Pakistan, Indonesia, and Malaysia. In 2012, Pakistan established the Naval Strategic Force Command (NSFC) to strengthen Pakistan’s policy of Credible Minimum Deterrence (CMD). The creation of the NSFC suggests a shift toward sea-based deterrence, complementing Pakistan’s broader military strategy. In December 2012, Pakistan conducted a series of cruise missile tests from naval platforms in the Arabian Sea. Given India’s expanding maritime capabilities, which Pakistan views as a significant threat, the Pakistan Navy may consider deploying tactical nuclear weapons on surface ships as part of its evolving deterrence strategy. Sri Lanka’s foreign policy cannot overlook this development.

Indonesia also emerged as a significant player in the evolving naval security landscape of the Indian Ocean. In 2010, it launched a military modernisation programme aimed at achieving a ‘Minimum Essential Force’ (MEF) by 2024. As part of this initiative, Indonesia sought to build a modern Navy with 247 surface vessels and 12 submarines. One of the primary challenges faced by the Indonesian Navy (TNI-AL) is piracy. To enhance maritime security, Indonesia and Singapore signed the SURPIC Cooperation Arrangement in Bantam in May 2005, enabling real-time sea surveillance in the Singapore Strait for more effective naval patrols. In 2017, Indonesia introduced the Indonesian Ocean Policy (IOP) and subsequently incorporated blue economy strategies into its national development agenda, reinforcing its maritime vision. According to projections from the Global Firepower Index, published in 2025, the Indonesian Navy is ranked fourth in global ranking and second in Asia in terms of Navy fleet strength (Global Firepower, 2025).

In October 2012, the Royal Malaysian Navy (RMN) announced plans to build a second Scorpène simulator training facility at its base in Kota Kinabalu, in addition to submarine base in Sepanggar, Sabah, constructed in 2002. To enhance its naval capabilities, the RMN planned to procure 18 Littoral Mission Ships (LMS) for maritime surveillance and six Littoral Combat Ships (LCS) between 2019 and 2023. Malaysia and China finalised their first major defence deal during Prime Minister Najib Razak’s visit to Beijing in November 2016. During this visit, Malaysia’s Defence Ministry signed a contract to procure LMS from China, as reported by The Guardian. Despite this agreement, Malaysia continues to maintain amicable relations with both China and India, as does Indonesia.

The increasing presence of major naval powers, the rise of regional stakeholders, and the growing significance of trade routes and maritime security have transformed the Indian Ocean into a central pivot of both regional and global politics, with Sri Lanka positioned at its heart. (To be Continued)

by Gamini Keerawella

Features

More excitement for Andrea Marr…

Sri Lankan Andrea Marr, now based in Australia, is in the spotlight again. She says she has teamed up with a fantastic bunch of Sri Lankan musicians, in Melbourne, and the band is called IntoGroove.

“The band has been going strong for many years and I have been a fan of this outfit for quite a few years; just love these guys, authentic R&B and funk.”

Although Andrea has her original blues band, The McNaMarr Project, and they do have a busy schedule, she went on to say that “when the opportunity came up to join these guys, I simply couldn’t refuse … they are too good.”

IntoGroove is Jude Nicholas (lead vocals), Peter Menezes (bass), Keith Pereira (drums), Blaise De Silva (keyboards) and and Steve Wright (guitar).

Andrea Marr: Powerhouse of the blues

“These guys are a fantastic band and I really want everyone to hear them.”

Andrea is a very talented artiste with many achievements to her credit, and a vocal coach, as well.

In fact, she did her second vocal coaching session at Australian Songwriters Conference early this year.

Her first student showcase for this year took place last Sunday, in Melbourne, and it brought into the spotlight the wonderful acts she has moulded, as teacher and mentor.

What makes Andrea extra special is that she has years of teaching experience and is able to do group vocal coaching for all styles, levels and genres.

In January, this year, she performed at the exclusive ‘Women In Blues’ showcase at Alfred’s On Beale Street (rock venue with live entertainment), in Memphis, in the USA, during the International Blues Challenge when bands from all over the world converge on Memphis for the ‘Olympics of the Blues.’

The McNaMarr Project with Andrea and Lindsay Marr in the

vocal spotlight

This was her fourth performance in the home of the blues; she has represented Australian Blues three times and, on this occasion, she went as ambassador for Blues Music Victoria, and The Melbourne Blues Appreciation Society’s ‘Women In Blues’ Coordinator.

Andrea was inducted into the Blues Music Victoria Hall of Fame in 2022 and released her 10th album which hit #1 on the Australian Blues Charts.

Known as ‘the pint-sized powerhouse of the blues’ for her high energy, soulful, original music, Andrea is also a huge fan of the late Elvis Presley and has checked out Graceland, in Memphis, Tennessee, USA, many times.

In Melbourne, the singer also plays a major role in helping Animal Rescue organisations find homes for abandoned cats.

Andrea Marr’s wish, at the moment, is that the Lankan audience, in Melbourne, would get behind this band, IntoGroove. They are world class, she added.

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoColombo Coffee wins coveted management awards

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoStarlink in the Global South

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoDaraz Sri Lanka ushers in the New Year with 4.4 Avurudu Wasi Pro Max – Sri Lanka’s biggest online Avurudu sale

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoStrengthening SDG integration into provincial planning and development process

-

Business4 days ago

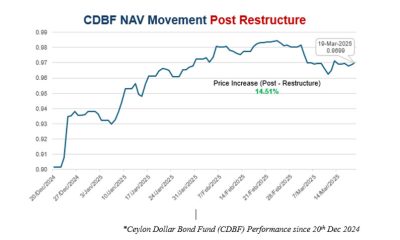

Business4 days agoNew SL Sovereign Bonds win foreign investor confidence

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoTo play or not to play is Richmond’s decision

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoModi’s Sri Lanka Sojourn

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoNew Zealand under 85kg rugby team set for historic tour of Sri Lanka