Features

Brilliant Bougainvillea

Short story

by Ruki Attygalle

The hospital matron glanced up from her desk and for a moment compassion clouded her eyes, as she looked at the small, frail woman standing before her desk, shakily holding out a typed sheet of paper.

“Ah…. you got our letter came on the 5.30 bus from Matara this morning. Matron Nona. I … I… can’t understand My son — Ranjit — has been transferred to the psychiatric ward?” Tears welled in Somawathie’s eyes.

The matron’s sigh was hardly noticeable. There were so many cases. Her training forbade emotional reaction.

She said gently, “His head wound is healing nicely. But you see, there are other problems.

“He was so much better the last time I saw him, about two weeks ago! The nurse also said so… .” Somawathie wiped her eyes with her sari pota and pushed back a strand of grey hair that had loosened itself from the small tight knot at the back of her head.

“Did he speak to you then? Has he said anything to you on any of your visits?”

“Yes … no … nothing much, because so much pain, no? His head all bandaged.” She blew her nose into a handkerchief which she took out from inside her hatte.

“Amme, I understand, but try and tell us. His bandages were off when you saw him, two weeks ago.”

“Yes, with the blessings of the gods! He was looking fine then That is why I thought he would be discharged soon.”

The matron sighed. It was always the same. Contradictions muddled thoughts, in times of stress. Gently she said, “This Amme. can you repeat to us even a word or two he said? You see, he refuses to talk to us.”

The overhead fan creaked, shifting humid air from one side’ of the room to the other. The work-worn hands of the mother twisted together nervously. Her eyebrows knit, deepening the already existing lines on her forehead as she tried to remember.’

“He – he was a quiet boy, never much of a talker. Kept to himself. Didn’t even join the village boys. They called him the upasakaya. We just could not believe it, when he said that he had joined the army.”

The matron interrupted. “Did your son say anything to you about how he got his injuries? Or anything at all?”

Somawathie’s bleary eyes took on a distant look as she tried to think back, to recollect. She remembered her fear for her son’s life when she was first told that he had been brought to the army hospital, with injuries to his head. She remembered seeing him lying on his side on the iron bed, with bandaged head and motionless body. She had stroked his arm gently, and bending over, asked him whether he could hear her. But he did not respond. Then a nurse led her away saying, “He is still in shock, and it’s best to let him rest now.”

The next time she visited him, a week later, he was seated in bed leaning against the bedhead with his eyes closed, his head still firmly bandaged. At first, she had thought he was in deep meditation, but then she saw his lips moving silently and presumed he was praying. She had waited in silence for a long time before she spoke.

“I have come to see you, Putha. Are you feeling better now?” Perhaps he hadn’t finished his prayers because he did not answer. She gave him more time, before she spoke again.

“Ranjit, look at me, Putha, I have come all the way from Matara to see you. Please speak to me.” Still silence. Yet she had continued trying to engage him in conversation.

“Tell me Putha, what happened to you? I was so relieved when they said that you had no gunshot injuries. How did it happen? Was it a bomb blast? We never get to hear what really happens to our children! Putha, please tell me what happened,” she pleaded.

Then he suddenly spoke, “I don’t know. I can’t remember,” but remained motionless with his eyes closed.

Somawathie continued talking to him although he had withdrawn once more into his lonely silence. She had told him about the bodhi poojas she was carrying out to bring about his full recovery; how the priest asked after him every time she went to the temple; that pirith was being chanted for him every day.

She touched his hand, but he remained unresponsive. Perhaps he was tired, she’d thought, and needed to rest. As she bent to touch his shoulder and bid him goodbye, she heard him whisper to himself, panati-pata veramanisikka padam samadiyami mouthing the precept to abstain from killing. He is observing his five precepts she had thought, but then, he seemed to be repeating the first precept over and over again, as though he had forgotten the rest.

The next time she saw him he was walking towards his bed returning from the toilet. His head had been shaven. The bandage had been removed and the back of his head was covered with dressing held together with bands of sticking plaster. He looked so different, but better, and she was pleased.

He had walked past her and sat on the bed. Obviously, he had seen her, she’d thought, so she walked up to him and laughing said, “So, now you only need a yellow robe and you can join the Sangha!”

He had turned his face away from her. Perhaps she had said the wrong thing, even though she had meant it to be light banter. She was happy to see him better, much better, and wanted him to feel good too.

She winced, as her mind raced back to the time when Ranji went missing for several hours after a row with his father. She had eventually found him seated under a coconut tree by the kamatha, his face swollen with crying. Eyes broody, unhappy.

“Where were you this morning?” his father had demand angrily.

“I was helping out at Sunday School, Thatha.”

“So, helping at Sunday School is more important than helping your father in the field? The field that brings you the rice that fills your belly? Do you call yourself a male?” he sneered.

“You are worse than a woman. Your sisters have more energy in them than you have. They are a credit to this household, unlike you. See how they work. All you can do is to get to a side and read books or creep to the temple! You may as well shave your head and go live in the temple!”

The derision in the father’s voice had hung heavy in the room like dark monsoon clouds. With head hung low, a sinking heart, trying to hold back tears of humiliation that stung his eyes, Ranjit cringed out of the house. His relationship with his father had never been an easy one. He had always known that he failed to measure up to his father’s expectations. Sitting under the tree brooding, he felt as though an old wound he had tried to keep at bay, to ignore, had started bleeding. His sense of inadequacy and alienation ran deep. I’ll show him that I am not the weakling he thinks I am. I will join the army.

“Putha,” said Somawathie, gingerly placing the comb of pIantains she’d brought for him on the bedside table. “Aren’t you going to look at the plantains I brought you? They are just how you like them – not overripe.” He took no notice.

“Ranjit, are you angry with me? I was only joking, Putha, about you looking like a Buddhist monk.” But he remained silent, his eyes fixed on the blank wall.

“Your sisters are worried about you. In fact, Prema wanted to come with me today, but I didn’t think she should be travelling such a long distance in her condition. The baby is due end of the month.” He didn’t seem to be listening.

“Why don’t you talk to me, Putha? Have I annoyed you?” “No,” he snapped, suddenly, harshly.

“Then why don’t you talk to me? I have come all the way from Matara and you won’t even look at me!”

“Amma! I need to think. I need time to remember. I have to sort things out,” he almost shouted at her, not hiding his annoyance. “What things Putha?”

He did not answer; but lay down on the bed and shut his eyes and shut her out.

The Matron’s voice brought her back to the present. “Try to remember his words,” she was saying.

“I think he didn’t like it when I joked with him and said he looked like a monk, with his shaven head.”

The Matron sighed. She had seen too many cases like this where there was no easy answer. But Ranjit had been an exceptionally docile patient, doing what he was told to do, never complaining. But this silence from a man, so young … something was wrong … radically wrong. Strange, that the window beside his bed was always kept closed with the curtains drawn. No sooner the nurse opened it, he’d get out of bed and shut it. How could he be helped if he wouldn’t even talk to the doctors?

The mother gingerly touched the Matron’s hand in a gesture of pleading. “What happened to my boy, Matron? How did he get hurt? We are never told.”

A division of the Sri Lanka Army, with Ranjit among 40 soldiers led by a Captain, were detailed to search a village in Vavuniya believed to be harbouring Tigers – cadres of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. Shooting had broken out, and hand grenades thrown at the soldiers.

“We lost 14 soldiers,” the matron said quietly. “Several were very badly wounded. Your son was lucky to have escaped with only a head injury. What is so strange is, that he seems to have been hit with a blunt instrument. He won’t tell us what happened.”

“That is because he does not know. He said he couldn’t member what happened.”

“Did he actually say so?” The matron queried eagerly.

“Yes,” said the mother, “He said he needed time to think. He said he needed time to remember.” His words rang strong in her mind now.

Time. Yes. Remembering what?

Ranjit walked slowly to the window. Although he tried not to look as he reached out to shut the window, he couldn’t help but notice from the corner of his eye the bougainvillea he now hated much. The creeper had hooked its treacherous thorns on to the trunk and branches of a mango tree, crept up stealthily and then burst into bloom. It was the colour he couldn’t stand.

It ‘wasn’t the common purple-red, nor an orange-red, rather, it was a deep, deep, red, the colour of blood. The colour that seeped through his eyes, and into his brain. It flooded inside and created a pressure in his head that was unbearable. It was worse than the pain of his wound. Why did they insist on opening the window!

He gently touched the dressing at the back of his head as he ,tried to remember for the umpteenth time what happened on that fateful day. The more he tried, the more his grip on his memory slipped away, his mind like a shattered mirror, its pieces scattered. As he tried to piece a few together, they disintegrate again into splintered fragments. A kaleidoscope of images’; scenes, noises, smells, feelings, memories – distant and recent advanced, receded, merged, unceasingly. He desperately strain

recognize a pattern; to insert the pieces of the jigsaw together and make up a picture he could comprehend.

Suddenly his body jerks with the sound of an explosion. A overpowering smell of gunpowder, blood, and singed flesh assail him. He is engulfed in the odour of death.

Then the kaleidoscope shifts and he is walking along a jungle path which, dream-like, turns into a field where the village boys are playing.

“Come and join us – we are catching grasshoppers,” they shout He shrinks back. “Are you afraid?” they taunt. “Grasshoppers don’t bite.”

“I’m not afraid of grasshoppers,” he affirms. Cupping his bands he traps a grasshopper on the ground. He feels its frantic movements against the hollow of his cupped palms.

“Grab it. Pick it up.” They bellow.

“No,” he says, “I may hurt it. It may die.”

“Coward! Coward! Coward!” they taunt with evil laughter. The word ‘coward’ ricochets in his head, as gunshots blast, around him.

“Shoot!” a voice booms behind him. “Shoot to kill. You blood coward shoot!”

His insides twist in fear as if an invisible band is clenching his guts. He lifts his gun and points at the young woman running towards him.

“Please don’t kill me. Please. Please,” she screams in Tamil as she draws closer with out-stretched arms. The white gemstone on her nostril glints as the sunlight catches it.

He places his finger on the trigger.

“Shoot!” the booming voice commands. “Shoot, you idiot!”

Images and sounds recede. Something tugs at him, sucking him down into a dark void of exhaustion; he struggles frantically and drags himself out slowly. The kaleidoscope shifts again.

His mother is seated cross-legged in her room on the cement floor. He is seated in her lap. She takes his little hands and places his palms together. He repeats the Pali stanza after her. Panatipata veramani sikkbapadam samadiyami . …

That’s the first precept she says. Then she explains what it means. You must never take the life of any living creature. Yes, not even an ant. Killing is a sin.

Suddenly the vision explodes like fireworks against his eyelids. Images pile one on top of another. Bodies thrown up in the air, coming down in pieces; blood and shattered bone; heads with eyeless black sockets. Shrill cries of terror.

The vision comes upon him again. The woman running towards him with outstretched arms. “Please, don’t kill me…

“Shoot! Shoot!”

He feels the coldness of the trigger on his forefinger. He feels the wetness of urine running down his leg.

“Coward! Coward! Coward!”

A gunshot echoes in his head. The woman crumples to the ground. He smells blood as he too collapses and lies on the parched earth. Intense pain stings like live coals at the back of his head.

“Ranjit,” the Matron’s voice grated on his raw nerves. “Your mother is here to see you.”

Ranjit’s fists clenched. Why couldn’t he be left alone! He needed to sort things out in his head. He needed to know what happened. He needed time to remember.

“Get out! Get out!” he screamed. “Just leave me alone.” Somawathie stepped back in shock, unbelieving, desperate.

Captain Welgama’s heavy boots stomped along the grey corridor behind the woman in the blue uniform. Suddenly, she slowed down, then stopped and looked at him.

“I’m telling you once again, Captain, Ranjit will not talk. He does not talk to anyone, and if he does, it will only be to chase you out.”

“But I need to talk to him Matron. It is important to me and perhaps to him too. I would have come earlier if I was allowed, but I was discharged from hospital only yesterday.” His voice was powerful even though he tried to speak softly. “You say he can’t remember what happened to him?”

“That’s what he told his mother. He does not speak to us.” They resumed walking.

The Captain frowned. “Maybe I could jog his memory. You see, we were fighting quite close to each other during the attack. saw him collapse, just before I got shot in my leg.”

He took out a handkerchief and wiped his face. “Tell me Matron, could Ranjit’s present problems be the result of the blow to his head?”

“I don’t know Captain, I’m not a doctor. Ranjit did suffer concussion. Sometimes, people can’t remember because they subconsciously block out memories, which are too painful. T here could be other reasons too for his loss of memory.”

The matron stopped at the entrance to Ward 12 and opened he door.

“Captain, I don’t think you should stay too long,” she murmured, moving towards the far end of the ward. Ranjit was lying on his bed with his eyes closed.

“You have a visitor, Ranjit,” the matron said with forced cheerfulness.

Ranjit screwed up his eyelids and tensed his body as if in anticipation of an onslaught. He was determined to resist any attempt to divert his attention from the vital task he had: to put together his shattered thoughts and make sense of the images that constantly besieged him.

“Hello Ranjit, how are you?” Captain Welgama tried to keep his voice down. “I would have come to see you earlier, but I was in hospital too. I was shot in my leg.” He dragged the chair that was against the wall by the window and sat by Ranjit’s bed.

Ranjit sat up as if galvanized by electricity. The voice boomed in his head echoing, vibrating like the sound of a gong. Shoot!

Shoot! Coward! Idiot! Shoot! His hands crumpled and clenched the bed sheet. His eyes stared at Captain Welgama unseeing. The captain stood up and placed his hands on Ranjit’s shoulders.

“I’m sorry, man, I’m truly sorry for what I did to you. I just lost control.”

Ranjit looked at Welgama, trying to, but not understanding him.

“I saw the woman running towards you, and you were in a better position to shoot. I couldn’t understand why you were, hesitating

The puzzle was slowly coming together in Ranjit’s head. “But’ she was asking to be spared, she was innocent, she was coming towards me with outstretched arms…

“Yes, but she could have been a suicide bomber. Why was she running towards you, instead of running away? What happened to all those months of training?”

“Was she…?”

“What?” Welgama interjected.

“A suicide bomber?”

“No, as it happens. But she could have been!”

Ranjit’s eyes were fixed on the bare wall, but his mind was seeing the woman, running towards him with her arms stretched out, pleading. He felt his hands lifting the gun as if in slow motion. He felt his finger on the trigger. The voice boomed from somewhere behind him. “Shoot! Shoot!” and suddenly his mind went blank.

The captain saw the anguish on the young man’s face and tried to say something to comfort him. But he couldn’t think of what to say. For a few moments they were locked in silence.

“You see, Ranjit,” Welgama said gently, as if speaking to a child, “by hesitating, you were putting so many lives in jeopardy. That is why I lost my temper. I brought my gun down on your head, with all the energy I could muster. It was such a savage blow; I might have killed you. I am sorry, Son.”

“I can’t remember you hitting me, or even falling down. I saw her falling after I’d shot her, and the next thing I remember is lying on the ground feeling a great pain in my head.”

“But you didn’t shoot her! That is why I hit you. I was behind you when I shot her. I shot her and then whacked you.”

Ranjit looked at the captain’s face, suddenly noticing his features for the first time. The deep-set eyes beneath his well-defined eyebrows, the slim long nose, the full lips and the slightly protruding teeth, and he felt a surge of gratitude. Gratitude to a man who helped him back to his senses; a man who’d lifted the heavy oppression that had been weighing him down, so long. The man who had used his gun on him with ferocity but now had brought resolution to his paralyzing mental turmoil.

“Did you say I didn’t kill her?” Ranjit wanted to hear it over and over again till every brain cell in his head was imbued with this knowledge. “Are you sure, Sir, are you sure?” Tension from his face and body was visibly easing. He felt a lightness of body and mind he had previously not experienced.

“Of course, you didn’t, man! I wish you had. Then you wouldn’t have suffered that head injury.” He walked to the window, drew the curtains apart and opened it. “It’s so hot, man, I don’t know how you stay in this room with the window closed!”

The curtains danced as a cool breeze blew in through the window.

“That is a beautiful bougainvillea,” commented the Captain, looking out. “It’s an unusual colour.”

Ranjit looked at the bougainvillea with new eyes. “Yes, Sir,” he said, “It is a brilliant colour.”

Features

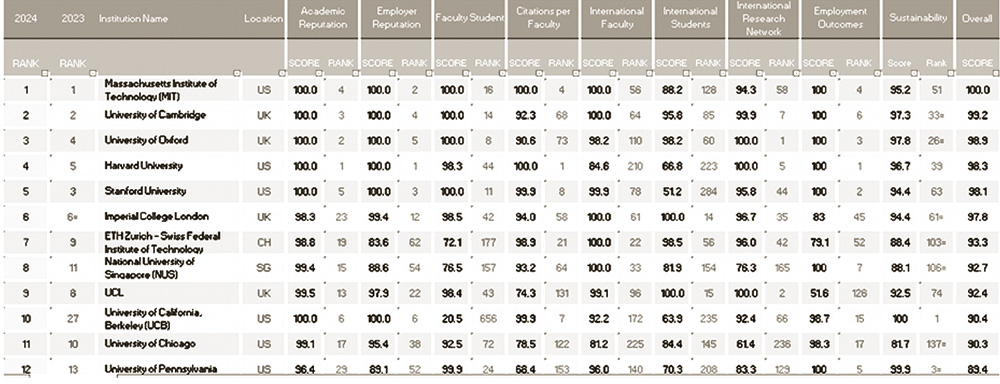

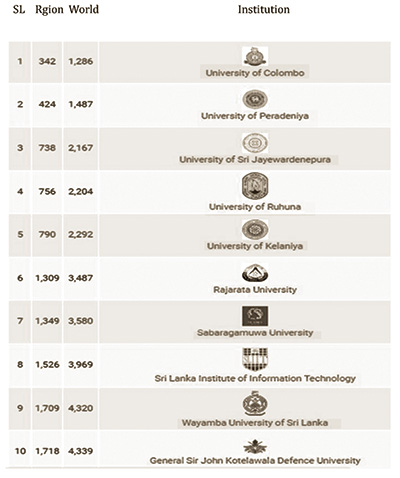

Why are SL universities’ positions low in world ranking indices?

Arespected law firm in New Zealand, when advertising positions for apprentice lawyers, tends to overlook applications from graduates who have not attended top-ranked institutions. Hence, it becomes crucial for universities to achieve international high rankings. Beyond scenarios like job searches, there are several reasons why a higher ranking holds significance for a university:

Arespected law firm in New Zealand, when advertising positions for apprentice lawyers, tends to overlook applications from graduates who have not attended top-ranked institutions. Hence, it becomes crucial for universities to achieve international high rankings. Beyond scenarios like job searches, there are several reasons why a higher ranking holds significance for a university:

https://www.adscientificindex.com/university-ranking/?funding=All+Universities&country_code=lk

Source: https://www.topuniversities.com/world-university-rankings

Prestige, Reputation and Research

A higher rank enhances the prestige and reputation of a university both nationally and internationally. It signifies academic excellence, research prowess, and overall institutional quality, attracting top students, faculty, and researchers. A higher rank provides global recognition and visibility to the university, positioning it as a leader in higher education and research. This recognition opens doors to international collaborations, partnerships, and exchange programmes, enriching the academic and cultural experiences of students and faculty.

Higher-ranked universities tend to have greater research impact and influence. They attract top researchers, secure more research funding, and produce groundbreaking discoveries and innovations that address societal challenges and drive economic growth.

Competitiveness and Attracting Talents

A higher rank increases the competitiveness of the university in attracting funding, grants, and partnerships. Funding agencies, philanthropic organisations, and industry partners are more likely to collaborate with highly ranked universities, leading to increased opportunities for research, innovation, and economic development.

Universities with higher ranks are more attractive to talented students, faculty, and researchers. Top-ranked universities can recruit and retain the best minds in academia, fostering a vibrant intellectual community and facilitating knowledge creation and dissemination.

Higher-ranked universities typically experience higher student enrollment and retention rates. Students are drawn to universities with strong academic reputations, diverse programme offerings, and attractive campus environments, enhancing the university’s revenue and sustainability.

The reputation and network of a higher-ranked university can positively impact the career prospects and success of its alumni. Graduates from prestigious universities often have access to better job opportunities, higher salaries, and influential professional networks, contributing to their long-term success and the reputation of the university.

Overall, a higher rank serves as a symbol of excellence, attracting talent, resources, and opportunities that contribute to the continued success and advancement of the university. The tables provide global rankings of universities, as well as rankings specific to the South Asian region and Sri Lanka.

Overall, a higher rank serves as a symbol of excellence, attracting talent, resources, and opportunities that contribute to the continued success and advancement of the university. The tables provide global rankings of universities, as well as rankings specific to the South Asian region and Sri Lanka.

Several factors contribute to Sri Lankan universities being ranked low:

Quality of Education and Research: Some Sri Lankan universities struggle to maintain high standards of education and research due to factors such as outdated curricula, inadequate teaching resources, and limited access to modern technologies and learning materials.

Low levels of research output and innovation contribute to the low rankings of Sri Lankan universities. Factors such as limited research funding, inadequate research infrastructure, and a lack of incentives for faculty to engage in research can hinder the production of high-quality research outputs.

Faculty Quality and funding: The quality and professional development of faculty members play a significant role in the rankings of universities. Challenges such as brain drain, where talented academics seek opportunities abroad due to better prospects, and limited opportunities for faculty development and training can impact the quality of teaching and research. Issues related to governance and management, including bureaucratic inefficiencies, lack of transparency, and political interference, can affect the overall functioning and performance of universities.

Sri Lankan universities often face challenges due to limited funding and investment in higher education. Insufficient financial resources can impact infrastructure development, research facilities, faculty recruitment, and student support services. Inadequate infrastructure and facilities, including outdated laboratories, libraries, and IT infrastructure, can hinder the ability of universities to provide quality education and conduct impactful research.

International Collaboration and Recognition: Limited international collaboration and recognition can also contribute to the low rankings of Sri Lankan universities. Engaging in partnerships with international institutions, participating in global research networks, and obtaining accreditation from reputable international organizations can enhance the visibility and reputation of universities.

The role of university administration

The factor of governance and management plays a significant role in influencing the encouragement or discouragement of research publication in quality journals indexed in databases like Scopus or Web of Science.

However, there seems to be a prevailing trend of publishing solely for the sake of meeting publication quotas in local journals that lack indexing, primarily to accumulate points for career advancement purposes.

Bureaucratic Inefficiencies: Inefficient bureaucratic processes within universities can create barriers and delays in the research publication process. For instance, complex administrative procedures for obtaining approvals such as ethical approval, funding, or accessing resources can discourage faculty members from pursuing research or submitting their work to quality indexed international journals. The time and effort required to navigate bureaucratic red tape may outweigh the benefits of publishing prestigious journals.

Lack of Transparency: Universities that lack transparency in their governance and decision-making processes may create an environment where researchers feel uncertain or insecure about the publication process. Without clear guidelines, criteria, and expectations for research publication, faculty members may hesitate to invest time and resources in producing high-quality research or submitting it to reputable journals. Additionally, concerns about favoritism, bias, or arbitrary decision-making in the publication process can undermine trust and confidence among researchers.

Political Interference: Political interference in university governance can have detrimental effects on research culture and academic freedom. When political agendas influence decision-making related to research priorities, funding allocation, or editorial policies, it may compromise the integrity and independence of academic research. Researchers may feel pressured to align their work with political interests or avoid controversial topics that could jeopardize their careers or funding opportunities. In such environments, there may be a tendency to prioritize quantity over quality in research output, with less emphasis on publishing in prestigious journals indexed in databases like Scopus or Web of Science.

Role of the Ministry of Education and the University Grant Commission

The University Grants Commission (UGC) serves as the governing authority for the university system in Sri Lanka, guided by nicely crafted vision, mission, and goals as per their website; https://www.ugc.ac.lk/

The absence of goals focused on “high impact research,” as outlined in the mission statement, highlights a potential gap in the UGC’s initiatives. This oversight may contribute to the lack of emphasis on promoting research publication in high-quality international journals, which is crucial for achieving higher ranks in ranking indices.

Further, in the promotion process for academics to the positions of Associate Professors and Professors, the University Grants Commission (UGC) has issued circulars outlining a point system; UGC Circular No. 723 of 12 December 1997, 869 of 30 November 2005, and 916 of 30 September 2009.

According to these circulars, a senior lecturer in the university system must accumulate 105 points to qualify for the Professor position, with a minimum of 55 points required from Research and Creative work. However, the conditions for claiming these points are relatively lax, requiring only that publications appear in numbered volumes and pass peer review. While there are no restrictions on maximum points, a critical issue remains: there is no minimum requirement for points articles published in globally recognized indexed journals.

Consequently, some faculties of certain universities resort to publishing their own “journals” and organizing “international conferences” to claim points without conducting rigorous research or publishing them in internationally reputed indexed databases.

Crucially, there should be a cap on the maximum points awarded for local publications, even if they are published by “recognized publishers,” a term not clearly defined in the circular. Publishers like Sarasavi, Vijitha, and Gunasena are well-known, yet citations from their publications are not acknowledged by WoS, Scopus or Google, thus not factored into rankings by agencies.

The Way out.

To boost Sri Lankan universities in global rankings, the UGC and Ministry of Education should revise their missions and goals to include more research and internationally recognized indexed publications for universities and ensure clear communication to prospective university staff.

Staff should receive more than just recognition for publications, with rewards such as cash incentives and public appreciation. Making research projects compulsory for undergraduates, postgraduates, and masters, and incentivizing manuscript submissions with marks or cash rewards, could further motivate students.

Conclusions

Overall, addressing issues related to governance and management is essential for fostering a conducive environment for research publication in quality indexed journals. Universities need to streamline administrative processes, enhance transparency in decision-making, and safeguard academic freedom from political interference. By promoting a culture of excellence, integrity, and meritocracy, universities can encourage faculty members to actively engage in research and contribute to knowledge dissemination through publications in reputable indexed journals.

Addressing these challenges requires concerted efforts from various stakeholders, including government authorities, university administrations, faculty members, students, and funding agencies. To elevate Sri Lankan universities in global rankings, the UGC and Ministry of Education should update their missions to prioritize research and internationally recognized publications. Additionally, staff should be rewarded beyond recognition, with incentives like cash rewards and public appreciation. Implementing compulsory research projects and incentivizing manuscript submissions can enhance student motivation at all academic levels.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT University, Malabe. He is also the author of the “Doing Social Research and Publishing Results”, a Springer publication (Singapore), and “Samaja Gaveshakaya (in Sinhala). The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the institution he works for. He can be contacted at saliya.a@slit.lk and www.researcher.com)

Features

Revival of Premadasaism: Way forward for Sri Lanka

By Dr. Mahim Mendis

Sri Lanka President’s Scholar, British Chevening Scholar, National University of Singapore Scholar and US State Department Post Doctoral Scholar

I was socialised in my childhood by an ardent Samasamajist father in Moratuwa. However, I became disillusioned in my youth, as I witnessed the ground level actions of the Samasamaja Party, working with Feudalists who pretended to be progressive.

I was not surprised when the LSSP was rejected by voters in the 1977 election. The void created in me was filled by Vijaya Kumaranatunge, when he formed the Mahajana Party with a principled position on social justice. When the JVP brutally murdered Vijaya in 1987, my hopes were dashed.

By the time I entered Kelaniya University, I was becoming a convert to ‘Premadasaism’ – the deep convictions found in the words and deeds of Ranasinghe Premadasa that I diligently followed.

I was mesmerised by the speeches of Premadasa, who articulated his pro-poor ideology of the UNP, the party, that my father opposed all his life. Today, I am convinced that Sri Lanka is fortunate that Premadasa has left for this nation a son named Sajith, who is inspired by Premadasa’s ideology and his simple lifestyle.

Pragmatic and Practical

While academics continue to talk about grand development theory, Ranasinghe Premadasa spent his life evolving a truly Sri Lankan development model to ensure and enable common people to reach excellence in all sectors of human development.

Youth of the land should not forget that Premadasa had the foresight to build the first ever, Day and Night Cricket Stadium, at Kettarama, long before we won the World Cup in 1996 and transformed Sugathadasa Stadium in line with top international benchmarks, encouraging younger athletes to reach excellence at the Olympics. He believed that Damayanthi Darsha, the South Asian Games Gold medalist should access the best schools of the land, paving the way for her to be educated at Ladies College, Colombo. He was impatient to see the bright rural youth shine unlike feudal politicians who preached one thing to the people and practiced another for their own children.

To serve the needs of common people, he established the Sevana Sarana Foster Parents scheme, to provide for the material needs of children. For this he mobilised the affluent to be socially sensitive to the bright, but poor children.

Today, it is not surprising to see his son Sajith inspired to do all this even before he forms a government.

Birth of Premadasaism

Premadasa harboured these grand ideals of Pro-People Development when he was a child of 15 years of age. He established the Sucharitha Movement in his own habitat Keselwatta, in the Colombo Central electorate.

Premadasa’s vision was far beyond Marxism of Kueneman or Communist Trade Unionism of L. W Panditha and the Temperance policies of F.R. Senanayake. He saw the beauty of holistic human development, balancing physical and material self-sufficiency of people with spiritual, emotional, and cultural self-sufficiency. He knew clearly that building a ‘Total Man’, would contribute towards a holistic ‘Total Society.’

As a social worker at the early age of fifteen, he celebrated the First Anniversary of the Sucharitha Movement with S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike and Mrs. Bandaranaike as Chief Guests, long before Bandaranaike ever thought of forming the SLFP.

Having entered politics in his youth under the tutelage of the eminent Labour leader A. E. Goonesinghe, Premadasa realised just as his political guru Goonesinghe realised, that Marxist inspired politicians coming from affluent backgrounds had severe limitations in their capacities as they were overwhelmed by their own unparalleled revolutionary rhetoric that made them lag in actions.

Premadasa would turn in his grave if he heard the emotionally and spiritually sterile NPP/Marxist rhetoric of today that husbands should remunerate their wives for their domestic labour.

Communicating Revolutionary Ideas in a Language Common Man Understood

Premadasa soon became the Youth Front Leader of AE Gunasinghe’s Labour Party and was able to explain about social emancipation to the common people- what Marxists like Peter Kuenemann in Central Colombo or Dr. N. M Perera of Ruwanwella could not explain in lingo understood by the poor.

When Premadasa opted to join the UNP, its leader Dudley Senanayake had the wisdom to appreciate this capacity, pitting young Premadasa against Dr. N. M Perera in Dr. Perera’s own electorate Ruwanwella, at the 1956 Parliamentary elections.

The election proved that the Marxist giant Dr. Perera could defeat young Premadasa, only by a margin of mere 6,228 votes.

Ironically ten years later, Dr Peter Kueneman, Dr. Colvin R. De Silva, Dr. S. A. Wickramasinghe and the other LSSP and Communist Party Parliamentary stalwarts had to retire from Parliamentary politics when they were politically annihilated by the UNP campaign that was led by the same Premadasa who was Deputy Leader of the UNP at the 1977 Parliamentary elections.

Humility of Premadasa and Arrogance of Distractors

President Premadasa was an extraordinary leader with a broad imagination. He was prepared to embrace Oxford educated Susil Siriwardena, a former Theoretician of the JVP, and listen to Wijeweera, attending conscientiously the proceedings of the Criminal Justice Commission in the aftermath of the First JVP uprising in 1971.

He extended his hand of friendship to them with conviction. However, Wijeweera was not prepared. Susil, who was a JVP theoretician, was wiser in correctly perceiving the mind of Premadasa.

The difference between Premadasa and Wijeweera, as my respected friend Dr. Dayan Jayatilleke makes clear is that unlike Wijeweera, Premadasa saw no place for violence in social system change as violence would have to be suppressed by the State at a severe cost to the very people whom they tried to emancipate. Ironically, JVP failed to appreciate this, due to arrogance on their part as stated by Dr. Jayatilleke in a recent interview with Kusum Wijetilleke- a trait that they still have not shed due to the inherent tendency to overestimate themselves.

In the late 1980’s, Premadasa appointed the National Commission on Youth Unrest, chaired by Professor G. L. Peiris, who made serious recommendations such as meritocracy, based employment and youth participation in politics.

Professor Peiris, who was appointed Vice Chancellor of Colombo University by President Premadasa, and Founder Chair of Pohottuwa, recently opted to join with Sajith Premadasa as he was convinced that Sajith.

Premadasa’s as a Champion of Inclusive Development

The 1978 Constitution purposefully alienated anti-establishment as well as ethnic minority parties from being represented in parliament. For this, JR Jayewardene’s Constitution had a purposeful, but unrealistic cut off point of 12 % in electoral performance for representation.

The present-day JVP should appreciate that Premadasa not only released more than 1,000 JVP activists when he came to power but brought down the cut off point for representation to 5%. Today, the JVP is represented in parliament, together with ethnic minority parties which continue to advocate shared political power.

While progressive Sri Lankans appreciate these social democratic political reforms, the very beneficiaries of these policies may not appreciate what Premadasa achieved for them with his powerful ethos of inclusive, value centered development for the common good of all Sri Lankans. However, many people will remember him as a genuine seeker of a new Social Contract.

Knowing Difference Between Extreme Capitalism and Extreme Socialism

Truly, cultured men and women have the capacity to be thankful for the progressive measures taken by Ranasinghe Premadasa. He was a true embodiment of social democracy, governing the entire social, political, cultural, and moral order. He was not a mere propagator of a social market economy, when he took over leadership from a right wing, J.R. Jayewardene led the UNP that tried to deprive Deputy Leader Premadasa of his well-earned presidential candidature in 1989. The same right-wing forces in the UNP, tried to impeach him together with Feudalist sympathizers, who lost all their social status due to Premadasaism

Cost of Disowning Premadasa Programme and Vision

Ironically, the so-called educated people of the land, who were found guilty of bankrupting the Sri Lankan economy are among those who disowned the Premadasa legacy that brought recognition, human dignity, and prosperity to our people.

As emphasised by world renowned social scientist, Dr. Howard Nicholas in an interview with Kusum Wijetilleke, his pessimism about Sri Lanka, turned into great optimism in late 1980s with the pro-people contribution of Ranasinghe Premadasa. This, as he says, was a time Sri Lanka was in a perilous condition with a total breakdown of institutions, aggravated by JVP and LTTE terrorism.

Promise for the Future: The Need for a Likeminded Leader

We need a visionary leader with the right mindset with a heart for the poor and for those who can generate wealth and transform Sri Lanka. We know that the options are very few. The heart and the mind of Premadasa is what is absent in the very people that Premadasa groomed for leadership, including the current President, Ranil Wickramasinghe.

Today, the only hope we see for our nation is Sajth Premadasa; Premadasa’s son who has the courage and foresight to commence an unprecedented Social Democratic programme.

Ranasinghe Premadasa, expounding his grand development vision as far back as 04 April, 1973, stated:

“Political power has been diffused amongst the people through the exercise of the franchise. In like manner, the economic wealth of the country should also be diffused amongst the people. We should evolve a scheme under which the public sector, the co-operative sector, the private sector, and a combination of all these three sectors – a joint sector – could function in competition with each other. Such competition will bring the maximum benefit to the people who need not become slaves of either a public or private monopoly. The government should ensure through its legislative and planning processes that the people participate in all aspects of development without allowing monopolies — state or individual.”

As a petitioner of the historic Supreme Court Case, in 2022, on bankrupting of the economy, which led to a historic verdict in favour of our petition, I would not have been moved to file action on behalf of the country’s entire citizenry, if not for my respect for the Premadasa ideology, which is continued and adapted to meet the challenges of modern Sri Lanka by his son, Sajith Premadasa.

Features

No escape from international human rights scrutiny

by Jehan Perera

In March 2020, the Sri Lankan government believed that the massive mandate President Gotabaya Rajapaksa had received gave it a licence to get out of the cycle of UN Human Rights Council resolutions by unilaterally opting out of the process. It announced that it would no longer consider itself bound to implement the resolution in force at that time. It stated its position was “backed by a people’s mandate and is in the interest of Sri Lanka and its people, instead of opting to continue with a framework driven externally that has failed to deliver genuine reconciliation for over four and half years.” However, the government also sought to keep itself within the framework of the UN system. The government stated that within a new framework of national reconciliation it was proposing it would continue to welcome the visits, advice and technical support from the UN system.

The re-emergence of the Easter Sunday bombing of 2019 into the mainstream of political debate is bound to have both domestic and international political consequences. Presidential elections are scheduled for October the latest. The UN Human Rights Council will meet in Geneva in September. The role played by Cardinal Malcolm Ranjith who gives leadership to the Catholic Church in the country is proving to be important in both. He has openly accused the government of being unresponsive to their search for the truth and justice. He complained that he and other members of the church had addressed a letter to the president “calling for a fresh and independent investigation into these attacks, but not even a letter of acknowledgement was sent to us.”

In a recent media interview, Cardinal Malcolm Ranjith stated that two political parties had met him and submitted their proposals for investigations of the Easter bombing if they win the forthcoming elections. The Cardinal has called upon those in his church not to vote for parties that have failed to make a commitment to truth and justice and presented concrete plans regarding this. The implications of this will have a bearing on the Catholic vote at the forthcoming elections. In addition, the Cardinal has announced that the Catholic Church is planning to present a proposal to the UNHRC. This is likely to have a detrimental effect on the government’s plan to extricate itself from the UNHRC process in Geneva.

OTHER CONFLICTS

The previous government’s bid to extricate itself from the UNHRC resolution by the strategy of unilateral withdrawal was not successful. Instead it led to a stronger resolution being passed the next time around which set up a special monitoring mechanism in Geneva to collect and safeguard evidence of human rights violations in Sri Lanka. This is especially worrisome to those in the government, especially those who can be accused of having violated human rights, as it opens the door to prosecution by any government or individual who files a case in an international court that accepts the principle of universal jurisdiction.

President Wickremesinghe is generally believed to have a special relationship with the international community and particularly with those Western countries that give special attention to international human rights. There has been considerable media coverage of his easy familiarity with heads of states at international conferences where the top leaders of the world fraternize with each other and with him. His latest achievement was in welcoming the President of Iran to Sri Lanka as a state guest at a time when the world is on tenterhooks due to Iran’s open clash with Israel which is backed by the Western world. The state media reported that “As in other countries, many people in Sri Lanka thought that the Iranian President Dr. Ibrahim Raisi would cancel the visit at the last minute. The current issue with the West is the proximate cause of this. But it is President Ranil Wickremesinghe who is leading Sri Lanka on a Non-Aligned path without angering the West and without angering the neighbour.”

There is a further reason for believing that Sri Lanka might be able to surmount the challenge of the UNHRC at the present time. This is due to the change in the international environment in which the Israel-Palestine conflict has taken a special place with the intensity of violence in Gaza exceeding that of Ukraine. These are both ongoing conflicts which ought to take priority in contrast to the Sri Lankan conflict which ended 15 years ago. Unlike Ukraine and Gaza, Sri Lanka is today a country without large-scale violence. Indeed, it is remarkable that there has not been a single incident of large-scale violence after the end of the war except for the mystery of the Easter bombing to which answers are not being found.

HIDDEN SUFFERING

International tourist guide books have selected Sri Lanka as the safest country in the world for a single woman to travel through on account of warmth and civility of the people and, of course, a well-functioning security system. In addition, where the post-war situation is concerned, the government is able to show a plethora of state mechanisms, ranging from multiple commissions of inquiry, the Office on Missing Persons, the Office of Reparations and most recently a Commission for Truth, Unity and Reconciliation which will be established soon. On the other hand, though Sri Lanka is at peace and able to offer a standard of hospitality that is seeing a boom in tourist arrivals, there is pain and suffering inside the society that needs to be taken care of and not neglected.

The largest scale of pain and suffering is due to the economic deprivation that suddenly hit people who were making ends meet, but who have found for the past two years that prices have tripled whilst their salaries remain the same. The World Bank’s most recent study on the impact of the economic collapse states that poverty has increased over the past four years—from 11 percent in 2019 to almost 26 percent in 2024 in Sri Lanka. It further states that approximately 60 percent of Sri Lankan households have decreased incomes, with many facing increased food insecurity, malnutrition and stunted growth.

The decision of Cardinal Malcolm Ranjith and the Catholic Church to take their unaddressed grievance to the UNHRC in Geneva is a sign of the pain and suffering due to injustice that continues to burn within the hearts and minds of people, especially those who fell victim and those who are involved with them. Whether or not Ukraine and Gaza figure in the forthcoming resolutions of the UNHRC, it can be expected that Sri Lanka which has been on the agenda will continue to remain on the agenda. Sustaining the present peace in Sri Lanka requires that change that goes beyond a change of faces in government. It requires a new governmental commitment that the two main opposition political parties are promising and the government needs to match.

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoSri Lanka Resorts of Cinnamon Hotels & Resorts mark Earth Day with impactful eco-initiatives

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoDialog Axiata recognised as the Most Significant FDI Contributor by BOI

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoUNESCAP Technical Cooperation Highlights Report flags significant strides in its partnership with Sri Lanka

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoComBank crowned ‘Best Bank in Sri Lanka’ by Global Finance for 22nd year

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoCinnamon Lakeside Colombo welcomes Nazoomi Azhar as its new General Manager

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoSri Lankan Oil and Gas exploration grinds to a standstill amid protracted legal battle

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoGerman research ship allowed Sri Lanka port call after Chinese-protest led clarification

-

Editorial5 days ago

Editorial5 days agoShocks from Bills