Midweek Review

Breaking the Cocoon: The Duality and Unity of a Dancer’s Body

By Dr Saumya Liyanage

Dance is an elusive art form. It is elusive in the sense that any type of dance form uses the human body as its expressive tool, and the art and the artist are one and the same. Dance is in a way similar to the actor’s art because the dancer uses her body as the means of expression. The actor and the dancer share this common ground where their art and the artistic tool are nonetheless inseparable and tightly intertwined. In order to understand the meaning of dance, one may need to separate the dancer’s body from dance but as stated the inseparability of the dancer from dance poses ontological questions as to who the dancer is and what dance is. Therefore, marking a boundary between the body and the work of dance is always blurred.

It is difficult to explain why people dance and how dance is differentiated from non-dance. Celeste Snowber writes that whether we dance and move our bodies, or whether our bodies are static and still, we always dance. She further argues that ‘we are all dancing and as we are all living, whether it is walking or running, swimming or hopping, jumping or being still. There is a dance of blood and fluid circulating in our bodies, and the expressivity of gestures is a daily activity’ (Snowber cited in Leavy, 2018, p. 247). In this analysis, Snowber broadly defines and blurs the distinction between dance and non-dance challenging us to rethink the way we define dance in the contemporary context.

Yet, Sri Lankan dance scholarship is still practised and confined within a particular school of thought that favours dance as a refined, codified body of movement. The learning of dance needs assiduous practice and dedication under a specific training regimen. Moreover, the dancer’s body should be physically trained and aesthetically beautiful to be able to perform and bring meanings to spectators. Hence traditional dance training and performance is purely cultivated through guru-shishya parampara (Teacher-disciple model) where the repetition and execution of learnt scores are supremely important. Very little space is allowed for the novice to explore physical possibilities beyond the regimented body. However, I am not skeptical about the skills and capacities that a traditional dancer possesses. Yet, this long assiduous practice and the regimentation of bodies along with cosmic teaching pertaining to demons and deities would undoubtedly affect and discipline not only the learner’s physicality but their thought process as well. Therefore, these pedagogical systems do not allow the learner to explore various expressions or movement culture.

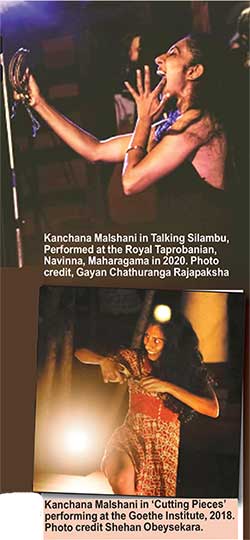

In this article, I am going to discuss about an emerging dancer and choreographer Kanchana Malshani and her recent work titled, Talking Silambu performed, at the Royal Taprobanian cultural hub in Navinna, Maharagama. In this piece of dance work, Kanchana raises several questions worthy of discussion through the current practice of dance pedagogy in Sri Lanka and ontological questions of what dance is, and who a dancer is. Further her work explores how dance can be a self-exploratory journey for those who seek alternative avenues through breaking their links to traditional forms and regimented bodies.

Kanchana

Kanchana Malshani has studied traditional Sri Lankan dance forms from various teachers since her childhood until she graduated from university. Kanchana is a graduate from Sripalee campus, University of Colombo and received a First Class honours degree. Being a student of traditional Sri Lankan dance forms such as Kandyan, Sabaragamuwa and Low country dance, Kanchana has developed her own style through her engagement with contemporary and experimental Sri Lankan dancers such as Venuri Perera and Umeshi Rajeendra. Learning and working with Venuri Perera and her influence on Kanchana’s reincarnation as a contemporary dancer is immense; in her ‘second life’ as a choreographer and dancer, she is being mentored by Venuri Perera. Her recent incarnation as a contemporary dancer signifies that she as a dancer needs a different life and expression within dance scholarship. Her recent work, Talking Silambu, shows a clear rebellious individuality that seeks to break the traditional codification and rebirth as a free bodied woman.

Kanchana Malshani has studied traditional Sri Lankan dance forms from various teachers since her childhood until she graduated from university. Kanchana is a graduate from Sripalee campus, University of Colombo and received a First Class honours degree. Being a student of traditional Sri Lankan dance forms such as Kandyan, Sabaragamuwa and Low country dance, Kanchana has developed her own style through her engagement with contemporary and experimental Sri Lankan dancers such as Venuri Perera and Umeshi Rajeendra. Learning and working with Venuri Perera and her influence on Kanchana’s reincarnation as a contemporary dancer is immense; in her ‘second life’ as a choreographer and dancer, she is being mentored by Venuri Perera. Her recent incarnation as a contemporary dancer signifies that she as a dancer needs a different life and expression within dance scholarship. Her recent work, Talking Silambu, shows a clear rebellious individuality that seeks to break the traditional codification and rebirth as a free bodied woman.

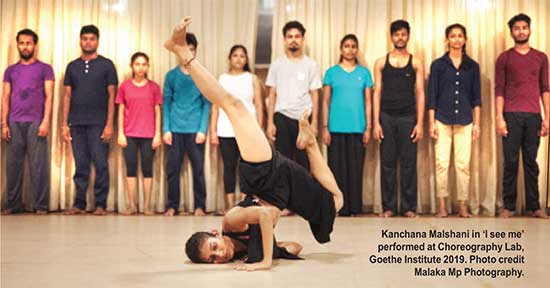

In 2017, Goethe Institute organised a Choreography Lab with dancer Venuri Perera, in Kalpitiya Sri Lanka. At this particular dance lab, Kanchana learnt contemporary dance from Yuko Kaseki, a Japanese Bhuto dancer, and Mahesh Umagiliya. Further, she learnt from Prof. Sandra Mathern-Smith, Professor of dance at Denison University, the USA, who has travelled several times to Sri Lanka as a Fulbright scholar. Her intervention in popularising and mentoring Sri Lankan dancers included a group of students at the University of the Visual and Performing Arts, Colombo, Sripalee campus, was also a turning point in her dance career. Dance teachers like Deepak Kurki Shivaswamy, Preethi Athreya, Maria Colusi have also helped Kanchana develop her skills. After receiving a half scholarship to visit a two-week-long dance camp at Sanskar Dance Festival India, she has been able to work with teachers such as Vittoria de Ferrari Sapetto and Roberto Olivan. Apart from her dance training, Kanchana has been working with one of the English Theatre companies, Stages Theatre, led by writer and director Ruwanthie De Chickera in Colombo. Kanchana may have undoubtedly learnt the value of being an artiste and professionalism in theatre through working in an actors’ ensemble at Stages Theatre.

Dance and Contemporaneity

The term ‘contemporary dance’ signifies specific meanings to dance specialists than non-specialists of dance. There are certain qualities that set contemporary dance apart from other genres. Contemporary dance can be distinguished from modern and other forms of dance because of its shift from the traditional narratology, dancer’s perspective, and breaking away from some of the dance prejudices to integrate text, words, digital and intermedial elements to it. One such difference is that contemporary dance work departs from traditional third person singular narrative to first person singular self-expression. This first person perspective allows the dancer to reflect her own auto-biographical material.

The term ‘contemporary dance’ signifies specific meanings to dance specialists than non-specialists of dance. There are certain qualities that set contemporary dance apart from other genres. Contemporary dance can be distinguished from modern and other forms of dance because of its shift from the traditional narratology, dancer’s perspective, and breaking away from some of the dance prejudices to integrate text, words, digital and intermedial elements to it. One such difference is that contemporary dance work departs from traditional third person singular narrative to first person singular self-expression. This first person perspective allows the dancer to reflect her own auto-biographical material.

Yet, these auto-ethnographic or auto-biographical narratives finally gets transformed into a political idiom.

Further contemporary dance deconstructs the aesthetic body celebrated in traditional dance and questions and dissects the skin of the dancer by opening up the inner flesh of the body. André Lepecki further identifies the uniqueness of contemporary dance from other genres because of its ‘ephemerality, corporeality, precariousness, scoring, and performativity’ (Kwan, 2017, p. 39). Thus, contemporary dance does not stick to a particular form, style or a structure. Instead it integrates various techniques, styles, and influences even from traditional dance forms to use the body as a political tool and the self as the centre of expression.

Talking Silambu

In this dance work titled, Talking Silambu, a twenty minute long piece of choreography, Kanchana appears in a non-traditional lose attire while wearing two Silambu (Silambu is a type of anklet made out of brass which Kandyan dancers wear when they perform) In the first instance, we hear the sound of Silambu as Kanchana’s legs begin to move. Yet, her dance body starts movement towards the audience while mixing traditional Kandyan dance codification with free body movement. It is clear that she performs half Kandyan and half improvised body movements in the score. In other words, her body movements are choreographed through semi-Kandyan codification mixed with free style movements. When the dance intensifies, she removes her Silambu, holding them in her hands and begins to shake them with vigorous body movements while throwing her body in various directions. At this point, Kanchana uses a trans-like act depicting trans-performance inherited particularly in low country devil dance. In this work, it is clearly demonstrated that her body is struggling with Silambu and trying to remove its connection to the body. This struggle culminates in the final phase of the dance work by indicating she runs away from the codified body and becomes a free woman. In this work, Kanchana demonstrates her discontent with the previous life as a traditional dancer and her struggle to break her affinity to the codified structure and beautification of the body in Kandyan dance. In a short conversation I had with Kanchana, she mentioned as particular rebirth that occurred at a dance camp organised by the Goethe Institute Colombo:

“I have been trained as a traditional dancer since my childhood but for the first time, working with this Japanese Butoh dancer, Yuko Kaseki, I learnt how to speak from my body. For many years I was living in a cage-tradition where I was entrapped. Living in this cage, I have performed what others wanted me to do. But in this dance lab, I found myself speaking to my own body and speaking through the body. I don’t want my body to be beautiful and aesthetically refined. I don’t want to display precision and codification of my body. I want to show how ugly I am and how vulnerable my body is.” (Kanchana, M., Pers. Comm. Dec. 2020).

Against the grain

In the traditional dance pedagogy, the dancer’s body is understood as a vehicle via which the dancer’s symbolic meanings are conveyed. There is a clear division between the inner and outer faculties in the dance body, and the dancer’s role is to bring forth those inner feelings to the onlooker via her body movements. This conceptualisation of the dancer’s body as a split between inner and outer is a complex issue pertaining to dance. Knowingly or unknowingly the dancer divides her body into body and mind and this Cartesian division has influenced the dancer to theorise the body and her craft.

In the traditional dance pedagogy, the dancer’s body is understood as a vehicle via which the dancer’s symbolic meanings are conveyed. There is a clear division between the inner and outer faculties in the dance body, and the dancer’s role is to bring forth those inner feelings to the onlooker via her body movements. This conceptualisation of the dancer’s body as a split between inner and outer is a complex issue pertaining to dance. Knowingly or unknowingly the dancer divides her body into body and mind and this Cartesian division has influenced the dancer to theorise the body and her craft.

Living in an ocular centric world, the dancer’s outer body is a place where womanhood is exploited for commercial purposes. From state-sponsored national festivals to television advertisements selling instant noodles or carbonated drinks, the dancer’s outer skin is commodified. Writing about Sri Lankan neo-dance traditions, propagated and performed at high profile delegations, product launches and in TV commercials in the country, I have written elsewhere that ‘women’s bodies succumb to the surgical knife of the choreographer whose male sexual desires are displayed on those bodies. Hence, no difference can be made between a choreographer and a cosmetic surgeon, whose expertise on women’s bodies, especially breasts and buttocks, are surgically transplanted and enhanced by incisions, stitches and staples’ (Liyanage, 2016). Amidst this commodification of female bodies in Sri Lankan dance arena, Kanchana’s attempt is to break away from this commodified, sexualised, and mechanised body to establish a non-codified and unified body of self-expression.

Here it is important for contemporary dancers to understand the value of the ‘living body’ or the ‘lived’ body that is celebrated in the vast literature of phenomenology and dance theory in the contemporary dance literature. In the dominant dance cultures from stage performances to digital and visual representations, the dancer’s skin is the most valued and emphasised. Now, with the contemporary dance turn, the dancer’s living or lived experience has come forth. Kanchana as a dancer now understands that her body is not a place for others to communicate vague meanings but a living entity where her own selfhood is reflected and displayed. It is a challenge for a dancer like her because the dominant female body has already been already established by key dance authors of the country. These dance authors have created a symbolic and sexualised female body for live and digitised performances. This symbolic and sexualised female body consists of the idealised female body for the male viewer. Kanchana is challenging this idealised body that is dominant in the real and digital world.

Dancer and Danced

The key juncture where the lived body differs from the symbolic body is that the symbolic body that is propagated in the media and elsewhere is the body that is not presented as a place for knowledge. Let me explain this further. In the traditional dance pedagogy, the dancer’s body is a place where meanings are generated and shared. In other worlds, the codified body is a canvas or a display where the onlooker extricates meanings. This codified, symbolic body is not presented to us as a place for knowing or sensing. Kanchana’s work and the work of other contemporary dancers suggest that we should understand the body as a place of sensing and knowing. This marks an epistemological turn in dance making and its reception. Dance, or the dancer’s body, has not been considered a place for ‘knowing’ in Sri Lankan dance pedagogy. Most often, a dancer narrates someone’s story or represents a third person singular perspective of the dance.

What Kanchana and the contemporary dance body suggest is to make a shift from the third person singular narrative to a first person singular perspective. This ‘I’ or the first person perspective allows the dancer to narrate her own stories and engagement with the social, cultural and political terrains. Further, a dancer as the author of her own work marks the departure of the dancer as an employer for a particular author. What Kanchana does in Talking Silambu is that as a dancer she tries to incarnate herself and narrate a story of searching a breakthrough and liberation. In this performance, her body works as a site of struggle and seeks the unity of her body and soul.

Conclusion

Understanding the body as a sensing and perceiving entity is still an alien concept to dance pedagogies in universities and private schools. Furthermore, dance can be a self-expressive and auto-ethnographic inquiry and is also a far-reaching idea for our students. Hence, the mainstream dance pedagogy produces dancers who dance without self-motivation to satisfy the audience who come to see symbolic representation of the body. Yet a handful of dancers who are eagerly exploring other avenues for dance expressions are also facing complex issues that their artistic interventions are not fully accepted in the mainstream dance scholarship in the country. Moreover, dancers like Kanchana have chosen a non-popular pathway to pursue their future dance careers and already faced deadlocks, as their artistic practices are not being accepted or sustained by institutions or organisations. Yet Kanchana is determined to break her cocoon to be incarnated as a hybrid moth.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Himansi Dehigama and Sachini Senevirathe for their assistance in preparing this paper. Further the author’s gratitude goes to dancer Kanchana Malshani.

References

Kwan, S. (2017). When Is Contemporary Dance? Dance Research Journal, [online] 49(3), pp.38–52. Available at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/dance-research-journal/article/when-is-contemporary-dance/8D44743A01A1ECC8100C5E65C1142DC2 [Accessed 4 Oct. 2019].

Leavy, P. (2019). Handbook of arts-based research. New York: The Guilford Press.

Midweek Review

A question of national pride

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake, who also holds the Finance and Defence portfolios, caused controversy last year when the Defence Ministry announced that he wouldn’t attend the National Victory Day event. Angry public reactions over social media compelled the President to change his decision. He attended the event. Whatever his past and for what he stood for as the President and the Commander-in-Chief of our armed forces, Dissanayake cannot, under any circumstances, shirk his responsibilities. The next National Victory Day event is scheduled in mid-May. The event coincides with the day, May 18, when the entire country was brought back under government control and the Army put a bullet through Prabhakaran’s head as he hid in the banks of the Nanthikadal lagoon, on the following day. The government also forgot the massive de-mining operations undertaken by the military to pave the way for the resettlement of people, rehabilitation of nearly 12,000 terrorists, and maintaining UN troop commitments, even during the war.

By Shamindra Ferdinando

The majestic presence of Field Marshal Sarath Fonseka, Admiral of the Fleet Wasantha Karannagoda and Marshal of the Air Force Roshan Goonetileke, though now more than 16 years after that historic victory, represented the war-winning armed forces at the 78 Independence Day celebrations. Their attendance reminded the country of Sri Lanka’s greatest post-independence accomplishment, the annihilation of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in May 2009.

Among the other veterans at the Independence Square event was General Shavendra Silva, the wartime General Officer Commanding (GOC) of the celebrated 58 Division. The 58 Division played a crucial role in the overall Vanni campaign that brought the LTTE down to its knees.

The 55 (GOC Maj. Gen. Kamal Gunaratne) and 53 Divisions (GOC Brig. Prasanna Silva) that had been deployed in the Jaffna peninsula, as well as newly raised formations 57 Division (GOC Maj. Gen. Jagath Dias), 58 Division and 59 Division (Brig. Nandana Udawatta), obliterated the LTTE.

Chagie Gallage, Fonseka’s first choice to command the 58 Division (former Task Force 1) following his exploits in the East, but had to leave the battlefield due to health issues then, rejoined the Vanni campaign at a decisive stage. Please forgive the writer for his inability to mention all those who gave resolute leadership on the ground due to limitations of space. The LTTE that genuinely believed in its battlefield invincibility was crushed within two years and 10 months. Of the famed ex-military leadership, Fonseka was the only one with no shame to publicly declare support for ‘Aragalaya,’ forgetting key personalities in the Rajapaksa government who helped him along the way to crush the Tigers, especially after the attempt on his life by a female LTTE suicide bomber, inside the Army Headquarters, when he had to direct all military operations from Colombo. And he went to the extent of addressing US- and India-backed protesters before they stormed President’s House on the afternoon of July 9, 2022. President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, wartime Defence Secretary, whose contribution can never be compared with any other, had to flee Janadhipathi Mandiyara and take refuge aboard SLNS Gajabahu, formerly of the US Coast Guard. The same sinister mob earlier ousted him from his private residence, at Mirihana, that he occupied previously without being a burden to the state. It was only after the attack on his private residence on March 31, 2022, that he came to reside in the official residence, the President’s House.

The presence of Fonseka, Karannagoda and Goonetileke at the Independence Day commemoration somewhat compensated for the pathetic failure on the part of the government to declare, during the parade, even by way of a few words, the armed forces historic triumph over the LTTE against predictions by many a self- proclaimed expert to the contrary. That treacherous and disgraceful decision brought shame on the government. Social media relentlessly attacked the government. To make matters worse, the elite Commandos and Special Forces were praised for their role in the post-Cyclone Ditwah situation. The Special Boat Squadron (SBS) and Rapid Action Boat Squadron (RABS), too, were appreciated for their interventions during the post-cyclone period.

The shocking deliberate omission underscored the pathetic nature of the powers that be at a time the country is in a flux. If Cyclone Ditwah hadn’t devastated Sri Lanka, the government probably may not have anything else to say about the elite fighting formations.

The government also left out the main battle tanks, armoured fighting vehicles, tank recovery vehicles and various types of artillery, as well as the multi barrel rocket launchers (MBRLs). The absence of Sri Lanka’s precious firepower on Independence Day shocked the country. The government owes an explanation. Lt. Gen. Lasantha Rodrigo of the Artillery is the 25th Commander of the Army. How did the Commander of the Army feel about the decision to leave the armour and artillery out of the parade?

The combined firepower of armour and artillery caused havoc on the enemy, thanks to deep penetration units that infiltrated behind enemy lines giving precise intelligence on where and what to hit.

The LTTE suffered devastating losses in coordinated attacks mounted during both offensive and defensive action, both in the northern and eastern theatres. The current dispensation would never be able to comprehend the gradual enhancement of armour and artillery firepower over the years to meet the growing LTTE threat. The MBRLs were a game changer. President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga’s government introduced the MBRLs in 2000 in the aftermath of devastating battlefield debacles in the northern theatre. (If all our MBRLs had been discarded after the successful conclusion of the war in May 2009, there is no point in blaming this government for non-display of the monster MBRLs. But, there cannot be any excuse for the government decision not to display the artillery.

Even during the three decades long war and some of the fiercest fighting in the North and East, the armour and artillery were always on display. It would be pertinent to mention the acquisition of Chinese light tanks in 1991, about a year after the outbreak of Eelam War II, and T 55 Main Battle Tanks (MBTs) from the Czech Republic, also during the early ’90s, marked the transformation of the regiment. Let me remind our readers that both Armour and Artillery were deployed on infantry role due to dearth of troops in the northern and eastern theatres.

No kudos for infantry

The Armour and Artillery were followed by the five infantry formations, Sri Lanka Light Infantry (SLLI), Sinha Regiment (SR), Gemunu Watch (GW), Gajaba Regiment (GR) and Vijayabahu Infantry Regiment (VIR). They bore the brunt of the fighting. They spearheaded offensives, sometimes in extremely unfavourable battlefield situations. The team handling the live media coverage conveniently failed to mention their battlefield sacrifices or accomplishments. It was nothing but a treacherous act perpetrated by a government not sensitive at all to the feelings of the vast majority of people.

The infantry was followed by the Mechanized Infantry Regiment (MIR). Raised in February 2007 as the armed forces were engaged in large scale operations in the eastern theatre, and the Vanni campaign was about to be launched, at the formation of the Regiment, it consisted of the third battalion of the SLLI, 10th battalion of SR and 4th battalion of GR. The 5th and 6th Armoured Corps were also added to the MIR. The 4th MIR was established also in February 2008 and after the end of war 21 battalion of the Sri Lanka National Guard was converted to 5 (Volunteer) MIR.

The contingent of MIR troops joined the Independence Day parade, without their armoured vehicles. Perhaps the political leadership seems to be blind to the importance of maintaining military traditions. Field Marshal Fonseka, who ordered the establishment of MIR must have felt really bad at the way the government took the shine off the military parade. What did the government expect to achieve by scaling down the military parade? Obviously, the government appears to be confident that the northern and eastern electorates would respond favourably to such gestures. Whatever the politics in the former war zones, the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP)-led Jathika Jana Balawegaya (JJB) must realise that it cannot, under any circumstances, continue to hurt the feelings of the majority community.

The description of Commandos and Special Forces was restricted to their post-Ditwah rehabilitation role. The snipers were not included in the parade. Motorcycle riding Special Forces, too, were absent. The way the Armour, Artillery, Infantry, as well Commandos and Special Forces were treated, we couldn’t have expected justice to other regiments and corps. In fact, the government didn’t differentiate fighting formations from the National Guard.

The National Guard was raised in Nov. 1989 in the wake of the quelling of the second JVP-led terrorist campaign. Mrs. Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s government swiftly crushed the first JVP bid to seize power in April 1971. The second bid was far worse and for three years the JVP waged a murderous campaign but finally the armed forces and police overwhelmed them. On Nov. 1, 1989, prominent battalions that had been deployed for the protection of politicians were amalgamated to establish the first National Guard battalion and upgraded as a new battalion of the Volunteer Force.

The Navy and Air Force, too, didn’t receive the recognition they deserved. Just a passing reference was made about the Fourth Attack Flotilla, the Navy’s premier offensive arm. The government also forgot the turning point of the war against the LTTE when Karannagoda’s Navy, with US intelligence backing, hunted down Velupillai Prabhakaran’s floating arsenals, on the high seas.

Karannagoda, the writer is certain, must have felt disappointed and angry over the disgraceful handling of the parade. The war-winning armed forces deserved the rightful place at the Independence Day parade.

The government did away with the fly past. Perhaps, the Air Force no longer had the capacity to fly MiG 27s, Kfirs, F 7s and Mi 24s. During the war and after Katunayake-based jet squadrons thundered over the Independence Day parade while the Air Force contingent was saluting the President. Jet squadrons and MI 24s (Current Defence Secretary Air Vice Marshal (retd) Sampath Thuyakontha commanded the No 09 Mi 24 squadron during the war (https://island.lk/govt-responds-in-kind-to-thuyaconthas-salvo/). Goonetileke’s Air Force conducted an unprecedented campaign to inflict strategic blows to the enemy fighting capacity. That was in addition to the SLAF taking out aerial targets and providing close-air-support to ground forces, while also doing a great job in helicopters whisking away troop casualties for prompt medical attention.

Chagie’s salvo

Maj. Gen Chagie Gallage

The armed forces paid a very heavy price to bring the war to a successful conclusion. During the 1981 to 2009 period, the Army lost nearly 24,000 officers and men. Of them, approximately 2,400 died during January-May 2009 when the Vanni formations surrounded and decimated the enemy. (Army, Navy and Air Force as well as police suffered loss of lives during the campaigns against the JVP in 1971 and during the 1987-1989 period) At the crucial final days of the offensive, ground forces were deprived of aerial support in a bid to minimise civilian losses as fleeing Tigers used Tamil civilians they had corralled as a human shield. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) as revealed by Wikileaks acknowledged the armed forces gesture but no government sought to exploit such unintentional support for Sri Lanka’s advantage. That wasn’t an isolated lapse.

In the run-up to the now much discussed 78 Independence Day parade, Gallage caused unprecedented controversy when he warned of possible attempts to shift the Security Forces Headquarters, in Jaffna, to the Vanni mainland. The GR veteran’s social media post sent shockwaves through the country. Gallage, known for his outspoken statements/positions and one of the victims of global sanctions imposed on military leaders, questioned the rationale in vacating the Jaffna Headquarters, central to the overall combined armed forces deployment in the Jaffna peninsula and the islands.

Regarding Gallage’s explosive claim, the writer sought clarification from the government but in vain. About a year after the end of the war, the then government began releasing land held by the armed forces. In line with the post-war reconciliation initiatives, the war-winning Mahinda Rajapaksa government released both government and public property, not only in the Jaffna peninsula, but in all other northern and eastern administrative districts, as well. Since 2010, successive governments have released just over 90 percent of land, once held by the armed forces. Unfortunately, political parties and various local and international organisations, with vested interests, continue to politicise the issues at hand. None of them at least bothered to issue a simple press release demanding that the LTTE halted the forcible recruitment of children, use of women/girls in suicide missions and end reprehensible use of civilian human shields.

The current dispensation has gratefully accepted President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s proposal to reduce the Army strength to 100,000 by 2030. Wickremesinghe took that controversial but calculated decision in line with his overall response to post-Aragalaya developments. The Island learns that the President’s original intention was to downsize the Army to 75,000 but he settled for 100,000.

Whatever those who still cannot stomach the armed forces’ triumph over the LTTE and JVP had to say, the armed forces, without any doubt, are the most respected institution in the country.

Maithripala Sirisena and Ranil Wickremesinghe can never absolve themselves of the responsibility for betraying the armed forces at the Geneva-based United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) in Oct. 2015. The treacherous JVP-backed the Yahapalana government to co-sponsor a US-led accountability resolution. That massive act of unprecedented betrayal should be examined taking into consideration primarily two issues – (1) the Tamil electorate throwing its weight behind Sirisena at the 2015 presidential election at the behest of now defunct Tamil National Alliance [TNA] (2) a tripartite agreement on the setting up of hybrid war crimes court. That agreement involved the US, Sri Lanka and TNA. Let me stress that at the 2010 presidential election, the TNA joined the UNP and the JVP in supporting war-winning Army Commander Fonseka’s candidature at the first-post war national election. Thanks to WikiLeaks, the world knows how the US manipulated the TNA to back Fonseka, the man who spearheaded a ruthless campaign that decimated the LTTE. Fonseka’s Army beat the LTTE, at its own game. Then, the Tamil electorate voted for Fonseka, who won all predominately Tamil speaking electoral districts but suffered a humiliating defeat in the rest of the country.

Let us not forget ex-LTTE cadres as well as members of other Tamil groups who backed successive governments. Tamil men contributed even to clandestine operations behind enemy lines. Unfortunately, successive governments had been pathetic in their approach to counter pro-Eelam propaganda. Sri Lanka never had a tangible action plan to counter those propagating lies. Instead, they turned a blind eye to anti-Sri Lanka campaigns. Dimwitted politicians just played pandu with the issues at hand. The Canadian declaration that Sri Lanka perpetrated genocide in May 2022 humiliated the country. Our useless Parliament didn’t take up that issue while three years later the Labour Party-run UK sanctioned four persons, including Karannagoda and Shavendra Silva, in return for Tamil support at the parliamentary elections there.

Victory parade fiasco

In 2016, the Yahapalana fools cancelled the Victory Day parade, held uninterrupted since 2009 to celebrate the country’s greatest post-independence achievement. By then, the Yahapalana administration had betrayed the armed forces at the UNHRC. The UNP-SLFP combine operated as if the armed forces didn’t exist. Sirisena had no option but to give in to Wickremesinghe’s despicable strategy meant to appease Eelamists whose support he desired, even at the expense of the overall national interest.

The Victory Day parade was meant to mark Sri Lanka’s triumph over separatist Tamil terrorism. It was never intended to humiliate the Tamil community, though the LTTE consisted of Tamil-speaking people. Those who complained bitterly about the May Victory Day celebration never wanted to publicly acknowledge that the eradication of the LTTE saved them from being terrorised any further. All concerned should accept that as long as the LTTE had the wherewithal to wage terror attacks, peace couldn’t have been restored. As Attorney-at-Law Ajaaz Mohamed repeatedly stressed to the writer the importance of UNP leader Wickremesinghe’s genuine efforts to address the national issue, he could have succeeded if the LTTE acted responsibly. The writer is also of the view that Wickremesinghe even risking his political future bent backwards to reach consensus at the negotiating table but the LTTE exploited the 2002 Ceasefire Agreement (CFA) arranged by Norway, to bring down Wickremesinghe’s government.

Wickremesinghe earned the wrath of the Sinhalese for giving into LTTE demands but he struggled to keep the talks on track. Then, the LTTE delivered a knockout blow to his government by withdrawing from the negotiating table, in late April 2003, thereby paving the way for President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga to take over key ministries, including Defence, and set the stage for parliamentary polls in April 2004. The LTTE’s actions made Eelam War IV inevitable.

The armed forces hadn’t conducted a major offensive since 2001 following the disastrous Agnikheela offensive in the Jaffna peninsula. Wickremesinghe went out of his way to sustain peace but the LTTE facilitated Mahinda Rajapaksa’s victory, at the presidential election, to create an environment which it believed conducive for the final war. Having killed the much-respected Foreign Minister Lakshman Kadirgamar, in August 2005, and made suicide attempts on the lives of Sarath Fonseka and Gotabaya Rajapaksa in April and Oct 2006, the LTTE fought well and hard but was ultimately overwhelmed, first in the East and then in North/Vanni in a series of battles that decimated its once powerful conventional fighting capacity. The writer was lucky to visit Puthumathalan waters in late April 2009 as the fighting raged on the ground and the Navy was imposing unprecedented blockade on the Mullaitivu coast.

The LTTE proved its capabilities against the Indian Army, too. The monument at Battaramulla where Indians leaders and other dignitaries, both military and civilian, pay homage, is a reminder of the LTTE fighting prowess. India lost nearly 1,500 officers and men here (1987 to 1990) and then lost one-time Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in a suicide attack in Tamil Nadu just over a year after New Delhi terminated its military mission here. The rest is history.

Midweek Review

Theatre and Anthropocentrism in the age of Climate Emergency

A few days ago, I was in a remote region of Sri Lanka, Hambantota, a dry zone area, where people mainly live on farming. The farming methods are still very primitive. I was engaged in a television series, titled Beddegama, directed by Priyantha Kolambage. The character I play is ‘Silindu’, a hunter. Silindu is a character created by Leonard Woolf, a colonial administrator, who lived in Sri Lanka in the early 20th century. In his widely read book, Village in the Jungle, Silindu, the hunter lives with his two daughters and his sister in a mud hut in the forest. They are one of the few families in this village struggling to survive amidst drought, famine and overbearing government authority.

Phenomenologically speaking, Silindu is an environmental philosopher. He believes that the jungle is a powerful phenomenon, a living entity. He thinks that the animals who live in the jungle are also human-like beings. He talks to trees and hunts animals only to dull the pangs of hunger. He is an ethical man. He believes that the jungle is an animate being and its animals are his fellow travellers in this world. His younger daughter, Hinnihami, breastfeeds a fawn. His sustainable living with fellow animals and nature is challenged by British law. He kills two people who try to dominate and suppress poor villagers by using their administerial powers. He is sentenced to death.

What I want to highlight here is the way our predecessors coexisted with nature and how they made the environment a part of their lives. Silindu’s philosophy of nature and animals is fascinating because he does not think that humans are not the centre of this living environment. Rather humans are a part of the whole ecosystem. This is the thinking that we need today to address the major environmental crises we are facing.

When I first addressed Aesthetica, the International conference on Performing Arts, as a keynote speaker, at Christ University, Bangalore, in 2018, in my keynote address, I emphasised the importance of understanding the human body, particularly the performing body as an embodied subject. What I meant by this term ‘embodied subject’ is that over the centuries, our bodies in theatre, rehearsal spaces and studios are being defined and described as an object to be manipulated. Even in modern dance, such manipulation is visible in the modernist approaches to dance. The human body is an object to be manipulated. However, I tried to show the audience that the performing body was not a mere object on stage for audience appreciation. It is a being that is vital for the phenomenological understanding of performance. The paradox of this objectification is that we objectify our bodies as something detached from the mind and similarly, we assume our environment, the world as something given for human consumption.

Performance and Sustainability

Just to bring the phenomenological lexicon to this discussion, I will draw your attention to one of the chapter in my latest book, titled, Lamp in a Windless Place: Phenomenology and Performance (2025) published by VAPA Press, University of Visual and Performing Arts, Colombo. This project is based on Sarah Kane’s famous play text 4.48 Psychosis. In this chapter I wrote phenomenological environmentalists explain the two ways that human beings interact and engage with the life-world. The one way of this engagement is defined as ‘involvement’ we involve with various activities in the world and it is one of the ways that we are being-in-the-world. The second way of being-in-this-world is that we ‘inhere’ in the world meaning that we are built with worldly phenomena or we are made out of the same stuff of our environment. (James cited in Liyanage 2025, pp. 98-99). This coupling and encroachment between our bodies and the environment occur mostly without our conscious interference. Yet, the problem with our human activities, and also our artistic practices is that we see our environment (human body) as an object to be consumed and manipulated.

Today, it is more important for us to change our mindsets to rethink our daily practices of performing arts and understand how human, nature, space and non-human species are vital for our existence in this world. Sustainable discourse comes into play with the United Nations initiative to make humans understand the major crises we are facing. In 2016, 195 parties agreed to follow the treaty of the Paris Agreement, which is mainly focused on climate change and the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels. Major scientists are talking about the ‘tipping points’. Tipping points indicate the current crisis that humans and other-than humans are going to face in the coming years.

Among those sustainable goals, the most important and the urgent point to be focused seems to be the climate emergency. Leading scientists of environmental sciences have already warned that within a few years, global warming will increase up to the level that the consequences will be catastrophic and dangerous to all, human and non-human. Ice sheets are shrinking; sea water level is increasing, and coral reefs are dying. It is becoming increasingly evident that countries in our region, particularly in South Asia, have been experiencing major climate shifts over the past few decades. Recent Cyclone Ditwah and the catastrophic flood devastated parts of not only Sri Lanka but also Malaysia, Sumatra, India, etc. Professor Missaka Hettiarachchi and Devki Perera published a landmark book, titled Nature – based method for water resource management (2025). In this work Hettiarachchi and Perera clearly argue that flood, erosion, and landslides are a part of the geological evolution and transformations. They are inherent activities in nature, which form new landscapes and conditions in natural environments. But the problem is that we experience these natural events frequently and they abruptly occur in response to human-nature collisions.

Climate Emergency

Professor Jeffry Sachs stresses the importance of taking action to prevent future climatic change. For him, we are facing three mega environmental crises: 1. Climate crisis leading to greenhouse gas emission due to fossil fuel burning. We have already come to the 1.5 warming limit now. He predicts that humans will experience 2.0 degree Celsius within two decades. 2. Second is the ecological crisis. This is the destruction of rainforests in South East Asia, Amazon and other regions. He argues that Amazon has reached the tipping point, meaning that the rain forest is in danger and it would be a dry land in a few decades time. Because of ocean acidification, scientists have already warned that we are in the wake of the destruction of coral reefs. The process is that high carbon dioxide dissolves in the water and it creates the carbonic acid. It causes the destruction of the coral reef system. 3. The third ecological crisis is the mega pollution. Our environment is already polluted with toxic chemicals, our waterways, ocean, soil, air and food chains are polluted. Micro plastics are already in our blood streams, in our lungs and even in our fetuses to be born.

The climate crisis is not just a natural catastrophe; it is political in many ways. Greenhouse gas emission is still continuing, and the developed countries such as the United States of America, Canada, China and Germany produce more carbon than the countries in the periphery. As Sachs rightly argues, the US politics is manipulated by the biggest oil companies in the world and President Trump is an agent of such multinational companies whose intention is to accumulate wealth through oil burning. Very recently, the US invaded Venezuela not to restore democracy but to gain access to the largest oil reserves in the country. We have seen many wars, led by the US, due to greed for wealth and natural resources. The US has withdrawn from the Paris agreement. President Trump calls climate change a hoax! So, the world’s current political situation is directly linked to the future of our environment, our resources and climate change.

Anthropocentrism in Performance

Back to creative arts. In the modernist era of our artistic practices and culture, we mimicked and replicated proscenium theatre inherited from Europe and elsewhere and revolutionised the ways that we see performance and perceiving. Our traditional modes of performance practices were replaced by the modern technology, architectural structures, studio training methods and techniques. Today, we can look back and see whether these creative arts practices have been sustainable with the larger human catastrophes that we experience almost daily. Eddie Patterson and Dr. Lara Stevenson have recently published an important and influential book, titled Performing Climate (2025). Being performance studies scholars, Patterson and Stevenson’s book contains 14 chapters interconnected and explores the human and non-human or more than human elements in the world. Patterson and Stevenson write that ‘performance is a messy business; a bloody mess’. ‘Performance is a mess of matter, climate, things, actors, and affects: neither a dramatic or postdramatic theatre but a network of dramaturgical elements; a site of birth and death, decay and renewal’ (Patterson and Stevenson, 2025, p. 1). In this book, they further explore the new ways of reading performance, making performance and perceiving performance. They argue that ‘we are interested in analyzing performance not as an insulated, exclusive art form predicated on human centrality but as a process that celebrates the transformative properties of waste – bacteria, debris and breakdown – composting and mulching within a larger network of bacteria, fungi and microbes embedded in the skin, air, soil and interacting with cellular networks and atmospheric conditions’ (ibid).

Our modern theatre has always been anthropocentric. Even in Sri Lanka, the father of modern Sinhala theatre, Professor Ediriweera Sarachchandra adapted traditional dance drama and developed a modern theatre for middle class theatregoers. This modern theatre was anthropogenic, patriarchal and marginalised the subaltern groups such as women, non-human beings, environment and so forth. The traditional dance and dramas, nadagam and kooththu were much more embedded in rituals performed by communities for various social, cultural and spiritual purposes were uprooted and established in the proscenium theatre for the audience, whose aesthetic buds were trained and sustained by the colonial theatre and criticism. Even traditional dance was uprooted from its traditional setting embedded in the ecosystem and placed on the proscenium theatre for the sake of modernisation of dance for the modern theatregoers. A new group of spectators, theatregoers, were produced to watch those performances which took place in city theatre buildings, insulated architectural spaces where the black boxes were lit up with expensive lighting technology and air-conditioning. As Patterson and Stevenson argue, the Western theatre has been obsessed with the human drama or autobiography. This western history of theatre has been ‘blind to the non-human agency and the natural world has always been in the background to the human centred stories’ (Patterson and Stevenson 2025).

Carbon Emission theatre

The performance practice that we have inherited and is continuing even today is highly problematic in the ways that we centre human agency over the non-human and the environment. This anthropocentric performance practice, as German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk called it, is ‘biospherical’. The biospherical theatre sees human action in the artificially constructed atmospheres for artistic innovations (Patterson and Stevenson 2025). Biospherical theatre is proto-laboratories and human greenhouses – in which able-bodied actors are trained and perform within air-conditioned black boxes; or more tellingly white people in white cubes’ (ibid).

Patterson and Stevenson further assert that ‘biospherical theatre is an enclosed Western form it is labour intensive, carbon intensive, hierarchical, exclusive, inaccessible extractive rather than generative of new knowledge and different ways of being with the world (ibid, p. 10). We inherited this hierarchical, exclusive, and carbon-oriented performance space from our past; as a colonial heritage. This colonial heritage of labour intensive, carbon intensive theatre is the major practice of performance in our societies. I am currently the Chairman of the National Theatre Sub-Committee under the purview of the Arts Council of Sri Lanka. Theatre practitioners today in Colombo are highly critical of the Ministry of Cultural Affairs for not having quality enclosed theatres in major cities in the country. They do not see the problems pertaining to the performance practice that is not ecologically sustainable for island nations like us.

We are possessed with the model of Globe theatre, which has been the model for theatre and entertainment in our regions for centuries now. However, today, we are forced to revisit and rethink this model of Globe theatre in the wake of the climate emergency. Patterson and Stevenson remind us that ‘inside these globes, art develops in enclosed and air-conditioned bubbles (laboratories, rehearsal rooms, conservatories, and galleries). This kind of theatre is biospherical: a human centric endeavour, evolving inside the globe, largely upholding the fantasy of itself as disconnected from atmospheric and environmental interactions beyond the human’ (Patterson and Stevenson 2025, p. 16).

Conclusion

According to Jim Bendell, it is not enough for us to develop resilience towards the climatic emergency; we need to embrace relinquishment (Stevenson, 2020, p. 89). It is the letting go of certain assets, behaviours and beliefs. Grotowski articulated this concept many decades back in his actor training at the Polish theatre laboratory. Grotowski developed the idea of via negative, letting go, or elimination for actors. Letting go of all the acculturations as Eugenio Barba articulates, to tap into the pure impulses and action. Grotowski even rejected the audience participation in his later works, para theatre, like Antonin Artaud, who rebelled against the dialogic, bourgeoisie theatre in France at the time. So, the modernist theatre directors have shown us that the Globe theatre is no longer a sustainable pathway for performance practice. It is time for us to rethink the carbon intensive, labour intensive, hierarchical, exclusive, and class-oriented theatre and performance.

References

Hettiarachchi, M., & Perera, D. (2025). Nature-Based Methods for Water Resources Engineering. The Institution of Engineers, Sri Lanka.

India Today Global. (2025, September 24). “U.S. government is in an open war against the Sustainable Development Goals”: Jeffrey Sachs. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qb4Jpqq4wvE

James, S. P. (2009). The Presence of Nature A Study in Phenomenology and Environmental Philosophy. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN IK.

Liyanage, S. (2025). Lamp in a Windless Place: Phenomenology and Performance. VAPA Press. (Original work published 2025)

SDSN. (2024, October 11). Sustainability Fundamentals with Jeffrey Sachs. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dJR0Q8ueQpc

Stevens, L. (2019). Anthroposcenic Performance and the Need For ‘Deep Dramaturgy’. Performance Research, 24(8), 89-97.

Stevens, L., & Varney, D. (2022). The Climate Siren: Hanna Cormick’s The Mermaid. TDR, 66(3), 107-118.

Woolf, L. (2012). The village in the jungle. Forgotten Books.

Author wishes to thank Himansi Dehigama for proofreading this manuscript.

Professor Saumya Liyanage is a professor of Drama and Theatre Currently working at the Department of Theatre Ballet and Modern Dance, Faculty of Dance and Drama, University of the Visual and Performing Arts, Colombo. He is the chairman of the State Theatre Subcommittee.

by Saumya Liyanage

Midweek Review

Islander Unbound

The pomp and pageantry of just a few hours,

Is not for him on this day in February,

When he’s been asked to think of things lofty,

Such as that he is the sole master of his destiny,

And that he’s well on track to self-sufficiency,

Rather, it’s time for that care-free feeling,

A time to zero in on the best of clothing,

Go for a carouse on the golden beaches,

And round-up pals for a cheering evening.

By Lynn Ockersz

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoMy experience in turning around the Merchant Bank of Sri Lanka (MBSL) – Episode 3

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoZone24x7 enters 2026 with strong momentum, reinforcing its role as an enterprise AI and automation partner

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoRemotely conducted Business Forum in Paris attracts reputed French companies

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoFour runs, a thousand dreams: How a small-town school bowled its way into the record books

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoComBank and Hayleys Mobility redefine sustainable mobility with flexible leasing solutions

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoAutodoc 360 relocates to reinforce commitment to premium auto care

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoHNB recognized among Top 10 Best Employers of 2025 at the EFC National Best Employer Awards

-

Midweek Review2 days ago

Midweek Review2 days agoA question of national pride