Features

BCC’s plan for the next hundred years

Breathing new life into domestic production:

By Vagisha Gunasekara

The need to turn the current economic crisis that was pushed off the edge by the COVID-19 pandemic into an opportunity to reconfigure national economies is the topic of many policy discussions, both in Sri Lanka and elsewhere. In June this year, addressing the 95th annual plenary session of the Indian Chamber of Commerce in Kolkata, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi said it is time to create an ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’. Although ‘Atmanirbhar’ loosely translates into “self-sufficient”, the Indian PM was not at all channelling Import Substitution policies in the 1960s and 70s. He was not referring to throwing out foreign companies from operating in India or large-scale nationalisation of industries. While Atmanirbhar entails a strong push to become self-sufficient in food, water and defense needs, the concept underlies the realization that a country cannot survive or economically thrive in isolation. It does not mean closing doors and borders to the world. Rather, it is an open-door policy that encourages foreign investment and goods to be manufactured in India and exported to the rest of the world and for products made in India to be sold in the global market. In other words, the aim of atmanirbhar is for India to become the next manufacturing hub of Asia and the rest of the world. The Government of India is already exploring various modalities with domestic and foreign investors and governments on how to redesign their economy in line with the spirit of atmanirbhar, and opening their economy in a much bigger way to the rest of the world.

Here at home, there is still hesitation among some circles about whether a small developing island nation like Sri Lanka can compete in the global market without the “economies of scale” advantage that larger markets like India have. But there is optimism around producing specific items that Sri Lanka may have an advantage in the global market, solely based on the quality of the product. Coconut oil is a case in point. In the past 10 years, the global demand for skyrocketed by 500% as it was identified as a “superfood” in the West.

To be specific, this demand is primarily for two products – virgin coconut oil and coconut water. In the United States alone, coconut water is now an 800-million-dollar industry. Globally, the coconut water industry is estimated to be worth around 2.2 billion dollars. The demand for coconut water is expected to increase by 27% by 2020. Similarly, the global industry value of virgin coconut oil was 2.1 billion dollars in 2016, and it is expected to be 4.2-billion-dollar industry in 2024. In the past five-six years, there is a steadily expanding niche market for coconut-based products such as coconut flour, coconut sugar and desiccated coconut. Furthermore, as Goldstein Research finds, the global beauty care industry, which is currently worth more than 10.3 billion dollars is gradually shifting to organic ingredients and coconut oil extracts in particular. Among the top five coconut consuming countries is the Philippines, United States, India, Indonesia and Vietnam (Export Development Board 2017).

In Sri Lanka, export earnings from coconut-based products has been increasing in recent years and much of it is attributed to industries surrounding virgin coconut oil (VCO), fresh king coconut, coconut cream and coconut milk. In 2017, the total revenue generated by exporting coconut-based products was 598 million dollars, which was a 3% increase from 2016 (Coconut Research Institute 2018).

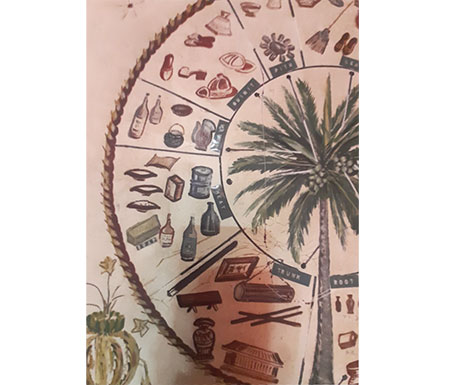

BCC Lanka Ltd is currently exploring an interesting modality to increase the production of coconut oil for cooking, wellness and other purposes both for domestic consumption and exportation. BCC is a household name in Sri Lanka. The company has a history that dates back to 1830s. According to the early records of the company, E. Price & Co. of the United Kingdom acquired patent rights for the technique of separating coconut oil into its solid and liquid parts. However, due to the irregular supply of raw material, the company set up crushing mills at Hultsdorf to separate oil directly from the kernels. The mills were set up in 1835 under a company set up in London called Hultsdorf Mills Co. (Ceylon) Ltd. The ownership of the mills changed hands between its inception and the World War I period and companies such as Wilson Richie & Co., G &W Leechman, and Freudenberg steering its operations.

In 1918, a powerful European syndicate operating in India tendered to purchase Hultsdorf Mills and it became British Ceylon Corporation (BCC). Since then, BCC operated in Sri Lanka, together with its fully owned subsidiaries such as British Ceylon Milling Company Ltd and Ceylon Extraction Company Ltd. Of the subsidiaries, in 1976 Ceylon Extraction Company Ltd ceased operations due to the lack of raw material that was required to sustain its minimum production capacity. In the period that followed, as a result of liberalisation reforms and changing political administrations, the company went through a period of decline, and this culminated in the sale of its most lucrative arm – Orient Co Lanka Ltd, which had the license for foreign liquor. In 1988, BCC Lanka was incorporated with the issue of 10,000,000 shares (held by the Treasury). Under the Conversion of Public Corporations and Government Owned Business Undertakings into Public Companies Act No. 23 of 1987. In order to trim the BCC workforce, a Voluntary Retirement Scheme was offered to its employees in 1991.

Following more privatisations in the 1990s and the lack of vision, leadership, government support and poor management resulted in further curtailment of the BCC operations and its workforce. However, when government policy shifted from a pro-privatisation position to one that was not in favour of selling off state enterprises, BCC Lanka commenced operations with minimum staff capacity in September 2006 and continues to produce and sell its number one product – refined coconut oil, both locally and internationally, along with a range of other products such as bath and laundry soap, washing powder, dish washing detergent and disinfectant.

The company appears to have received a new lease of life under the current policy trend of strengthening the viability of domestic industries. As the situation triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic has renewed interest in increasing the capacity of domestic production, BCC seems to be making plans to get back into business in a bigger and better way. During a recent visit to the BCC premises at Meeraniya Street, Colombo 12, the management revealed its plan to expand it operations and increase its competitiveness in the domestic and international market. Currently, BCC produces roughly 250 metric tonnes of refined coconut oil and 160 metric tonnes of soap and other items in a year. This, however, is well below the maximum production capacity of the company. The new strategy to increase coconut oil production is aimed at making productive use of BCC’s underutilised machinery and storage facilities, and also will carve out revenue prospects for the collaborating partner companies.

The most notable component of BCC Lanka’s new strategy is the consolidation of their supply chain for the production of coconut oil. The company is launching a partnership among BCC and three state-owned enterprises – National Livestock Development Board (NLDB), Kurunegala Plantation Ltd., and Chilaw Plantation Ltd., – and the Mahaweli B zone in order to ensure an uninterrupted supply of green coconuts in order to produce refined coconut oil. NLDB is one of the largest semi-government organisations whose core business is dairy farming. In addition to dairy and other poultry-related ventures, NLDB owns and maintains 4,545 hectares of coconut estates in the island’s “coconut-triangle”. Chilaw Plantations Ltd is a government-owned company managed by the Public Enterprise Development Ministry. Currently, they own 3,825 hectares of coconut plantations. Kurunegala Plantations Ltd is also a government-owned company with 5,244 hectares of coconut plantations. Its core business activities include cultivation, production, processing, and sale of coconuts. BCC Lanka will serve as the Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) and undertake downstream activities in producing edible oil. The strategic alliance among the four companies and the Mahaweli B zone is expected to ensure an uninterrupted supply of coconuts. Green coconuts collected from all four supply hubs will be transported to a central oil mill, where the initial production will take place. The central oil milling facility is a new investment proposed under the current strategic plan. Thereafter, the base coconut oil will be delivered to BCC’s refinery unit, where the value-addition process will take place. From that point onwards, BCC will take over downstream operations such as labelling, packaging, marketing, and sales. The intention is for these products to enter domestic retail markets, online shopping platforms and the export market through direct dealers, distributing agents and strategic sales partners. Given the expanding trend of the global market for coconut oil and other coconut-based products, increasing the production, marketing and sales of coconut oil and reviving state-owned companies like the BCC and its partners is a welcome move by the Ministry of Small & Medium Business and Enterprise Development, Industries and Supply Chain Management.

The second component of BCC’s strategic plan is to develop a modern, 7-storey multi-purpose commercial centre using a 6-acre portion of BCC’s current premises in Meeraniya Street. The compensation funds that BCC will obtain from giving up a parcel of their current premises to construct a court complex will be directed to the construction of the new commercial centre. Furthermore, the current management of BCC has plans to restore the original Chairman’s bungalow (located in Colombo 12) which is currently in a dilapidated state into a commercialised heritage establishment. The colonial charm of the bungalow and BCC’s collection of old machinery that were used during the colonial period is sufficient basis for this venture and a tasteful transformation of this site into a tourist attraction will undoubtedly add aesthetic and commercial value to what the currently has to offer.

BCC’s new strategic plan and its renewed motivation to strengthen its capacity, operations and relevance both nationally and internationally is a refreshing step, particularly given the sad situation of Sri Lanka’s state-owned enterprises. Currently, Sri Lanka has over 400 SOEs, employing over a million employees, however, running on an aggregate annual loss of USD 27 billion. SOEs are seen by ordinary citizens as employment- not service providers that consume an extraordinary amount of public resources and assets. Political interference, corruption, inefficient recruitment and management practices, low productivity and the lack of autonomy in decision-making have long been identified as constraints to developing SOEs. Like BCC, the Valachchenai paper mill and the Paranthan chemical factory also seem to have risen from the ashes given the renewed interest in strengthening domestic industrial production. Acknowledging BCC’s strategic plan which carries the objective of securing its presence and relevance for the next 100 years, and the resumption of activities in Valachchenai and Paranthan factories, it would be timely for BCC and for other SOEs to set up sound governance practices, accountability mechanisms, and performance-based incentive structures and focus on improving productivity and efficiency, financial discipline, transparent and effective treasury management and credit control and technological advancement. Lastly, the management and the overall leadership must keep in mind that politicisation of SOEs has long been identified as a curse that has eventually run these enterprises to the ground. As this is ingrained in Sri Lanka’s political culture, it might be challenging to change the status quo. However, if the leadership is keen that local industries remain active and relevant for another 100 years, such structural issues must not go unaddressed.

Features

Rebuilding Sri Lanka: 78 Years of Independence and 78 Modules of Reform

“The main theme of this year’s Independence Day is “Rebuilding Sri Lanka,” so spoke President Anura Kumara Dissanayaka as he ceremonially commemorated the island’s 78th independence anniversary. That was also President AKD’s second independence anniversary as President. Rebuilding implies that there was already something built. It is not that the NPP government is starting a new building on a vacant land, or whatever that was built earlier should all be destroyed and discarded.

Indeed, making a swift departure from NPP’s usual habit of denouncing Sri Lanka’s entire post independence history as useless, President AKD conceded that “over the 78 years since independence, we have experienced victories and defeats, successes and failures. We will not hesitate to discard what is harmful, nor will we fear embracing what is good. Therefore, I believe that the responsibility of rebuilding Sri Lanka upon the valuable foundations of the past lies with all of us.”

Within the main theme of rebuilding, the President touched on a number of sub-themes. First among them is the he development of the economy predicated on the country’s natural resources and its human resources. Crucial to economic development is the leveraging of our human resource to be internationally competitive, and to be one that prioritises “knowledge over ignorance, progress over outdated prejudices and unity over division.” Educational reform becomes key in this context and the President reiterated his and his government’s intention to “initiate the most transformative era in our education sector.”

He touched on his pet theme of fighting racism and extremism, and insisted that the government “will not allow division, racism, or extremism and that national unity will be established as the foremost strength in rebuilding Sri Lanka.” He laid emphasis on enabling equality before the law and ensuring the supremacy of the law, which are both necessary and remarkable given the skepticism that is still out there among pundits

Special mention was given to the Central Highlands that have become the site of repeated devastations caused by heavy rainfall, worse than poor drainage and inappropriate construction. Rebuilding in the wake of cyclone Ditwah takes a special meaning for physical development. Nowhere is this more critical than the hill slopes of the Central Highlands. The President touched on all the right buttons and called for environmentally sustainable construction to become “a central responsibility in the ‘Rebuilding Sri Lanka’ initiative.”. Recognizing “strong international cooperation is essential” for the rebuilding initiative, the President stated that his government’s goal is to “establish international relations that strengthen the security of our homeland, enhance the lives of our people and bring recognition to our country on a new level.”

The President also permitted himself some economic plaudits, listing his government’s achievements in 2025, its first year in office. To wit, “the lowest budget deficit since 1977, record-high government revenue after 2006, the largest current account balances in Sri Lanka’s history, the highest tax revenue collected by the Department of Inland Revenue and the sustained maintenance of bank interest rates at a long-term target, demonstrating remarkable economic stability.” He was also careful enough to note that “an economy’s success is not measured by data alone.”

Remember the old Brazilian quip that “the economy is doing well but not the people.” President AKD spoke to the importance of converting “the gains at the top levels of the economy … into improved living standards for every citizen,” and projected “the vision for a renewed Sri Lanka … where the benefits of economic growth flow to all people, creating a nation in which prosperity is shared equitably and inclusively.”

Rhetoric, Reform and Reality

For political rhetoric with more than a touch of authenticity, President AKD has no rival among the current political contenders and prospects. There were pundits and even academics who considered Mahinda Rajapaksa to be the first authentic leadership manifestation of Sinhala nationalism after independence, and that he was the first to repair the rupture between the Sri Lankan state and Sinhala nationalism that was apparently caused by JR Jayewardene and his agreement with India to end the constitutional crisis in Sri Lanka.

To be cynical, the NPP or AKD were not the first to claim that everything before them had been failures and betrayals. And it is not at all cynical to say that the 20-year Rajapaksa era was one in which the politics of Sinhala nationalism objectively served the interests of family bandyism, facilitated corruption, and enabled environmentally and economically unsustainable infrastructure development. The more positive question, however, is to ask the same pundits and academics – how they would view the political authenticity of the current President and the NPP government. Especially in terms of rejecting chauvinism and bigotry and rejuvenating national inclusiveness, eschewing corruption and enabling good governance, and ensuring environmental stewardship and not environmental slaughter.

The challenge to the NPP government is not about that it is different from and better than the Rajapaksa regime, or than any other government this century for that matter. The global, regional and local contexts are vastly different to make any meaningful comparison to the governments of the 20th century. Even the linkages to the JVP of the 1970s and 1980s are becoming tenuous if not increasingly irrelevant in the current context and circumstances. So, the NPP’s real challenge is not about demonstrating that it is something better than anything in the past, but to provide its own road map for governing, indicating milestones that are to be achieved and demonstrating the real steps of progress that the government is making towards each milestone.

There are plenty of critics and commentators who will not miss a beat in picking on the government. Yet there is no oppositional resonance to all the criticisms that are levelled against the government. The reason is not only the political inability of the opposition parties to take a position of advantage against the government on any issue where the government is seen to be vulnerable. The real reason could be that the criticisms against the government are not resonating with the people at large. The general attitude among the people is one of relief that this government is not as corrupt as any government could be and that it is not focused on helping family and friends as past governments have been doing.

While this is a good situation for any government to be in, there is also the risk of the NPP becoming too complacent for its good. The good old Mao’s Red Book quote that “complacency is the enemy of study,” could be extended to be read as the enemy of electoral success as well. In addition, political favouritism can be easily transitioned from the sphere of family and friends to the sphere of party cadres and members. The public will not notice the difference but will only lose its tolerance when stuff hits the fan and the smell becomes odious. It matters little whether the stuff and the smell emanate from family and friends, on the one hand, or party members on the other.

It is also important to keep the party bureaucracy and the government bureaucracy separate. Sri Lanka’s government bureaucracy is as old as modern Sri Lanka. No party bureaucracy can ever supplant it the way it is done in polities where one-party rule is the norm. A prudent approach in Sri Lanka would be for the party bureaucracy to keep its members in check and not let them throw their weight around in government offices. The government bureaucracy in Sri Lanka has many and severe problems but it is not totally dysfunctional as it often made out to be. Making government efficient is important but that should be achieved through internal processes and not by political party hacks.

Besides counterposing rhetoric and reality, the NPP government is also awash in a spate of reforms of its own making. The President spoke of economic reform, educational reform and sustainable development reform. There is also the elephant-in-the-room sized electricity reform. Independence day editorials have alluded to other reforms involving the constitution and the electoral processes. Even broad sociopolitical reforms are seen as needed to engender fundamental attitudinal changes among the people regarding involving both the lofty civic duties and responsibilities, as well as the day to day road habits and showing respect to women and children using public transport.

Education is fundamental to all of this, but I am not suggesting another new module or website linkages for that. Of course, the government has not created 78 reform modules as I say tongue-in-cheek in the title, but there are close to half of them, by my count, in the education reform proposals. The government has its work cut out in furthering its education reform proposals amidst all the criticisms ranged against them. In a different way, it has also to deal with trade union inertia that is stymieing reform efforts in the electricity sector. The government needs to demonstrate that it can not only answer its critics, but also keep its reform proposals positively moving ahead. After 78 years, it should not be too difficult to harness and harmonize – political rhetoric, reform proposals, and the realities of the people.

by Rajan Philips

Features

Our diplomatic missions success in bringing Ditwah relief while crocodiles gather in Colombo hotels

The Sunday newspapers are instructive: a lead story carries the excellent work of our Ambassador in Geneva raising humanitarian assistance for Sri Lanka in the aftermath of Ditwah. The release states that our Sri Lankan community has taken the lead in dispatching disaster relief items along with financial assistance to the Rebuilding Sri Lanka fund from individual donors as well as members of various community organizations.

The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies In Geneva had initially launched an appeal for Swiss francs CHF 5 million and the revised appeal has been tripled to CHF 14 million to provide life saving assistance and long term resilience building for nearly 600,000 of the most vulnerable individuals; the UN office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs has contributed US$4.5 million; the WHO has channeled US$175,000; In addition, our mission is working closely with other UN and International organizations in Geneva for technical support to improve disaster preparedness capacity in the long term in Sri Lanka such as through enhanced forecasting to mitigate risks and strengthen disaster preparedness capacities.

In stark contrast it is ironic to see in the same newspaper, a press release from a leading think tank in Colombo giving prominence to their hosting a seminar in a five star hotel to promote the extraction of Sri Lanka’s critical minerals to foreign companies under the guise of “international partners”. Those countries participating in this so called International Study Group are Australia, India, Japan and the US, all members of a regional defence pact that sees China as its main adversary. Is it wise for Sri Lanka to be drawn into such controversial regional arrangements?

This initiative is calling for exploitation of Sri Lanka’s graphite, mineral sands, apatite, quartiz, mica and rare earth elements and urging the Government to introduce investor friendly approval mechanisms to address licencing delays and establish speedy timelines. Why no mention here of the mandatory Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) or traditional public consultations even though such extraction will probably take place in areas like Mannar with its mainly vulnerable coastal areas? Is it not likely that such mining projects will renew commotion among poor mainly minority communities already badly affected by Ditwah?

It would be indeed pertinent to find out whether the think tank leading this initiative is doing so with its own funds or whether this initiative is being driven by foreign government funds spent on behalf of their multinational companies? Underlying this initiative is the misguided thinking defying all international scientific assessments and quoting President Trump that there is no global climate crisis and hence environmental safeguards need not be applied. Sri Lanka which has experienced both the tsunami and cyclone Ditwah is in the eye of the storm and has been long classified as one of the most vulnerable of islands likely to be effected in terms of natural disasters created by climate change.

Sri Lanka’s mining industry has so far been in local hands and therefore it has been done under some due process protecting both local workers involved in handling hazardous materials and with some revenue coming to the government. What is now being proposed for Sri Lanka is something in the same spirit as President Donald Trump visualized for redeveloping Gaza as a Riviera without taking into consultation the wishes of the people in that land and devoid of any consideration for local customs and traditions. Pity our beautiful land in the hands of these foreigners who only want to exploit our treasure for their own profit and leave behind a desolate landscape with desperate people.

by Dr Sarala Fernando

Features

The Architect of Minds – An Exclusive Interview with Professor Elsie Kothelawala on the Legacy of Professor J. E. Jayasuriya

This year marks a significant milestone as we commemorate the 35th death anniversary of a titan in the field of education, Professor J. E. Jayasuriya. While his name is etched onto the covers of countless textbooks and cited in every major policy document in Sri Lanka, the man behind the name remains a mystery to many. To honour his legacy, we are joined today for a special commemorative interview. This is a slightly expanded version of the interview with Professor Elsie Kothelawala. As a former student who rose to become a close professional colleague, she offers a rare, personal glimpse into his life during his most influential years at the University of Peradeniya.

Dr. S. N. Jayasinghe – Professor Kothelawala, to begin our tribute, could you tell us about the early years of Professor J. E. Jayasuriya? Where did his journey start?

Prof. Elsie Kothelawala – He was born on February 14, 1918, in Ahangama. His primary education actually began at Nawalapitiya Anuruddha Vidyalaya. He then moved to Dharmasoka College in Ambalangoda and eventually transitioned to Wesley College in Colombo. He was a brilliant student, in 1933, he came third in the British Empire at the Cambridge Senior Examination. This earned him a scholarship to University College, Colombo, where he graduated in 1939 with a First-Class degree in Mathematics.

Q: – His professional rise was meteoric. Could you trace his work life from school leadership into high academia?

A: – It was a blend of school leadership and pioneering academia. At just 22, he was the first principal of Dharmapala Vidyalaya, Pannipitiya. He later served as Deputy Principal of Sri Sumangala College, Panadura.

A turning point came when Dr. C.W.W. Kannangara invited him to lead the new central school in the Minister’s own electorate, Matugama Central College. Later, he served as Principal of Wadduwa Central College. In 1947, he traveled to London for advanced studies at the Institute of Education, University of London. There, he earned a Post Graduate Diploma in Education and a Master of Arts in Education. Upon returning, he became a lecturer in mathematics at the Government Teachers’ Training College in Maharagama. He joined the University of Ceylon’s Faculty of Education as a lecturer in 1952 and later, in 1957, he advanced to the role of Professor of Education. Professor J. E. Jayasuriya was the first Sri Lankan to hold the position of Professor of Education and lead the Department of Education at the University of Ceylon.

The commencement of this department was a result of a proposal from the Special Committee of Education in 1943, commonly known as the Kannangara Committee.

Q: – We know he left the university in 1971. Can you tell us about his work for the United Nations and UNESCO?

A: – That was a massive chapter in his life. After retiring from Peradeniya, he went global. He moved to Bangkok to serve as the Regional Advisor on Population Education for UNESCO. He spent five years traveling across Asia, to countries like Pakistan, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Malaysia, helping them build their educational frameworks from the ground up.

Even after that, his relationship with the United Nations continued. He returned to Sri Lanka and served as a United Nations Advisor to the Ministry of Education for two years. He was essentially a global consultant, bringing the lessons he learned in Sri Lanka to the rest of the world.

Q: – How did you personally come to know him, and what was the nature of your professional relationship?

A: – I first encountered him at Peradeniya during my Diploma in Education and later my MA. He personally taught me Psychology, and I completed my postgraduate studies under his direct supervision. He was notoriously strict, but it was a strictness born out of respect for the subject. The tutorials were the highlight. Every day, he would select one student’s answer and read it to the class. It kept us on our toes! He relied heavily on references, and his guidance was always “on point.” After my MA, he encouraged me to apply for a vacancy in the department. Even as a lecturer, he supervised me, I had to show him my lecture notes before entering a hall.

Q: – He sounds quite imposing! Was there any room for humor in his classroom?

A: – He had a very sharp, dry wit. Back then, there was a fashion where ladies pinned their hair in high, elaborate piles. He once remarked, “Where there is nothing inside, they will pile it all up on the outside.” Needless to say, that hairstyle was never seen in his class again!

Q: – Looking at the 1960s and 70s, what reforms did he promote that were considered innovative for that time?

A: – As Chairman of the National Education Commission (1961), he was a visionary. He promoted the Neighborhood School Concept to end the scramble for prestige schools. He also proposed a Unified National System of education and argued for a flexible school calendar. He believed holidays should vary by region, matching agricultural harvest cycles so rural children wouldn’t have to miss school.

Q: – One of his major contributions was in “Intelligence Testing.” How did he change that field?

A: – He felt Western IQ tests were culturally biased. He developed the National Education Society Intelligence Test, the first standardized test in national languages, and adapted the Raven’s Non-Verbal Test for Sri Lankan children. He wanted to measure raw potential fairly, regardless of a child’s social or linguistic background.

Q: – How would you describe his specific contribution to the transition to national languages in schools?

A: – He didn’t just support the change, he made it possible. When English was replaced as the medium of instruction, there was a desperate lack of materials. He authored 12 simplified Mathematics textbooks in Sinhala, including the Veeja Ganithaya (Algebra) and Seegra Jyamithiya (Geometry) series. He ensured that “language” would no longer be a barrier to “logic.”

Q: – After his work with the UN and UNESCO, why did he become known as the “Father of Population Education”?

A: – While in Bangkok, he developed the conceptual framework for Population Education for the entire Asian region. He helped dozens of countries integrate population dynamics into their school curricula. He saw that education wasn’t just about reading and writing, it was about understanding the social and demographic realities of one’s country.

Q: – Madam, can you recall how Professor Jayasuriya’s legacy was honoured?

A: – Professor Jayasuriya was truly a unique personality. He was actually one of the first Asians to be elected as a Chartered Psychologist in the U.K., and his lectures on educational psychology and statistics were incredibly popular. During his time at the University of Ceylon, he held significant leadership roles, serving as the Dean of the Faculty of Arts and even as acting Vice Chancellor. His impact was so profound that the Professor J. E. Jayasuriya Memorial Lecture Theatre at the Faculty of Education in Peradeniya was named in his honor.

Beyond his institutional roles, he received immense recognition for his service, including honorary D. Lit and D. Sc degrees from the University of Colombo and the Open University, respectively. Perhaps his most global contribution was his ‘quality of life’ approach to population education developed for UNESCO in the mid-1970s. As O. J. Sikes of UNFPA noted in the International Encyclopedia on Education, it became the predominant teaching method across Asia and is still considered the fastest-growing approach to the subject worldwide.

Q: – Finally, what is the most profound message from his life that today’s educators and policymakers should carry forward?

A: – The lesson is intellectual integrity. When the government’s 1964 White Paper distorted his 1961 recommendations for political gain, he didn’t stay silent, he wrote Some Issues in Ceylon Education to set the record straight.

He believed education was a birthright, not a competitive filter. Today’s policymakers must learn that education policy should be driven by pedagogical evidence, not political expediency. As our conversation came to a close, Professor Elsie Kothelawala sat back, a reflective smile on her face. It became clear that while Professor J. E. Jayasuriya was a man of rigid logic, and uncompromising discipline, his ultimate goal was deeply human, the upliftment of every Sri Lankan child.

Thirty-five years after his passing, his presence is still felt, not just in the archives of UNESCO or the halls of Peradeniya, but in the very structure of our classrooms. He was a pioneer who taught us that education is the most powerful tool for social mobility, provided it is handled with honesty. As we commemorate this 35th memorial, perhaps the best way to honor his legacy is not just by remembering his name, but by reclaiming his courage, the courage to put the needs of the student above the convenience of the system.

Professor Jayasuriya’s life reminds us that a true educator’s work is never finished, it lives on in the teachers he trained, the policies he shaped, and the national intellect he helped ignite.

by the Secretary J.E.Jayasuriya Memorial Foundation : Dr S.N Jayasinghe

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoZone24x7 enters 2026 with strong momentum, reinforcing its role as an enterprise AI and automation partner

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoSLIM-Kantar People’s Awards 2026 to recognise Sri Lanka’s most trusted brands and personalities

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoAll set for Global Synergy Awards 2026 at Waters Edge

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoAPI-first card issuing and processing platform for Pan Asia Bank

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoHNB recognized among Top 10 Best Employers of 2025 at the EFC National Best Employer Awards

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoGREAT 2025–2030: Sri Lanka’s Green ambition meets a grid reality check

-

Editorial4 days ago

Editorial4 days agoAll’s not well that ends well?

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoPhew! The heat …