Features

Battling the Tea Board and vested trade interests

“Tea Hub” was a toxic proposal that would have hurt pure Ceylon tea

(Excerpted from the Merrill. J. Fernando autobiography)

My fervent appeals to the Tea Board for assistance to local brand builders to develop own brands were, as I said earlier, supported by Victor Santiapillai. My strategy proposal to launch ‘Dilmah’ in Australia as a fully Sri Lankan-owned tea brand was the first such initiative presented to the Tea Board. The Board was enthusiastic and voted the funds I solicited – approximately Australian Dollars 300,000 (Rs. 5.9 million then).

However, the Secretariat bureaucracy, without consulting me, submitted a paper proposing that my project, and all future projects, should be funded on 50/50 basis, between the Board and the exporter. This was, actually, a great blow to my plans, as a tea bagging project is an enormously costly exercise, requiring extensive investment in plant and machinery.

The opposition to my project from the Secretariat is demonstrated by one single fact; the Dilmah initiative went before the Funding Committee – consisting of Government nominees of the Board – no less than 21 times, before it was approved! The many projects which were approved at a single sitting disappeared from view within a short space of time. The Dilmah project, approved so grudgingly by this Funding Committee, is the only such initiative still in successful operation.

Finally, following comprehensive clarifications on brand building and launching expenditure submitted by me to the Tea Board, supported by Santiapillai, as I have mentioned earlier in this chapter, it was agreed that such costs would be shared on an equal basis by the EDB, Tea Board, and Dilmah. Despite the delayed approval, my project continued to be plagued by the tardiness and active opposition by key members of the Secretariat.

The Tea Board share of the promotional costs was unduly delayed, causing me and my distributor in Australia serious embarrassment. Dr. Wickrema Weerasooria, then High Commissioner for Sri Lanka in Australia, had to intervene several times on my behalf with the Chairman of the SLTB, though his appeals were stifled by the Secretariat. At no stage in these painful exercises did I appeal for assistance to the Plantations Minister, Major Jayawickrema, who had ceased to be my father-in-law 12 years previously.

Today, Dilmah carries the message of Pure Ceylon Tea to over 100 countries worldwide. Had I succumbed to the animosity generated against the Dilmah project at the outset, today there would not be one locally-owned label, selling successfully in overseas markets dominated by multinationals. As opposed to that, over the decades the Tea Board has invested millions of dollars, fruitlessly, in a multiplicity of tea promotional projects, but Dilmah remains the only success story, proving beyond doubt that my company was the right partner then for the EDB/SLTB project, to represent Pure Ceylon Tea in an overseas market.

More conflict

One of the main reasons for my numerous conflicts with the long-established trade bodies was their general resistance to change and to my insistence on a more proactive approach from those bodies. The industry in Sri Lanka, on account of its vulnerability to both internal and external dynamics consumption patterns, international financial upheavals, regional conflicts and many more is a highly-volatile system. Our trade governance and regulatory bodies seemed to be entrenched in an archaic mindset, with a singular inability, or reluctance, to offer proactive responses to predictable market disruptions. The tendency seemed to be to jealously guard the status quo.

Once, in a move to change the entrenched ‘clubbiness’ of the CTTA, we enabled the election of Lofty Wijeratne, then a Director of Carsons, as Chairman. Despite requests from many members of the trade, I steadfastly refused to consider the position myself. Lofty, too, was subject to many pressures from vested interests within. I recall a request he made to me, obviously due to compulsion from established

brokers, not to support Ajit Chitty’s application for a tea broker’s license. I disagreed and persisted in my support of Ajit, as I was of the firm view that the trade should encourage the emergence of more local companies. Finally, Ajit entered the broking fraternity with Eastern Brokers and made a very good thing of it.

I am also aware that during this period, when I was involved with numerous issues impacting on the interests of the local exporter, CTTA representatives had been instructed by the relevant British masters to oppose any and all of my initiatives and proposals. In the many years of its existence, the CTTA has, on the whole, done a reasonable job in protecting and fostering industry interests. However, my view is that the constant pressures brought on it by a wide spectrum of industry-related parties and entities has, in recent decades, prevented it from a strict and objective pursuit of its mandate.

When the British dominated every aspect of the tea industry, there was no dissent or conflict of interest, as there was tacit agreement that the CTTA and every other trade-related body was committed to the protection of British interests. The Chamber of Commerce too was not free of this type of internal manipulation and inbuilt politicking. One year I was appointed to the committee of the Chamber. At my very first meeting, a very senior member with strong interests in banking brought in a related issue which was not on the agenda. My objection to the discussion of this item, on those very grounds, was accepted and the matter was dropped immediately.

Within two weeks, Suneetha Jayawickreme, who was then Secretary of the Chamber, called me to advise that a regulation of the Chamber precluded two individuals from the same group of companies from serving on the committee simultaneously. He pointed out that Jayasingham of Harrisons & Crossfield and I were both on the Harrisons Travel Services Board, and that in compliance with the Chamber stipulation, I should resign. I immediately did so, without even waiting for a written confirmation of the discussion. I was actually amused that interested parties had used a legitimate convention, though the association was tenuous, to ease out an individual who was, obviously, not prepared to toe the general line.

I must also state that the criticisms I have leveled against all these boards is in connection with their administration and trajectories as of the early 1970s and across the ’80s. That era is now history, though the consequences of both inaction and misdirected strategies of that time were long-term impediments to the development of the country’s tea export trade. The thinking within those entities is far more balanced and enlightened now, the Tea Exporter’s Association excluded, for reasons which I will explain in a subsequent chapter.

An attempted reconciliation

When a group of traders decided that their parochial interests should supersede industry welfare in its totality, and sought to launch the Tea Exporters’ Association (TEA), I believe that all traders, without exception, supported the move. Several senior members invited me to join but I refused, giving them very good reasons for my opposition to it. One of the members was the late Michael de Zoysa, then Managing Director of Lipton and for many years a prime mover in the CTTA.

He and I frequently disagreed with each other on a number of important trade-related issues. After his retirement from Lipton also he approached me on several occasions and tried to persuade me to join the TEA, on the grounds that the trade was now thinking differently and that they would like to consider my views seriously and work together for common goals.

At first I refused to engage in any discussion on the matter but, finally, after several personal approaches by Michael, I agreed to meet a six-member team of trade representatives led by him. During his years at Lipton, our frequently-conflicting views on common trade-related issues had led to a certain frostiness in our relationship, although we had known each other for years.

I appreciated that as a senior manager of a multinational trader, which he had joined straight from school, he was obliged to guard its interests which, however, were generally inconsistent with those of the local exporter of a locally-owned brand. Things between us changed substantially after his retirement, though, and our relationship became more relaxed, particularly because, once freed from the professional obligation of serving the narrow interests of a multinational, he was able to take a more objective and liberal view of the trade.

Fate, however, does not respect human motives or human plans. Tragically, Michael died suddenly and, instead of chairing the meeting that was scheduled to be held at my home on September 30, 2019, I attended his funeral on that day. Along with Michael, the possibility of a reunification of divergent tea trade interests was also laid to rest. Despite our differences, we treated each other with respect, as we were both men with strong opinions on subjects that were also our passion.

The tea hub – a toxic proposal

In my view, in no other concept or proposal, is the venality of many of our tea traders and their submissiveness to colonial and multinational domination, as clearly demonstrated, as in the arguments that have been offered in support of the ‘Tea Hub’ hypothesis. In essence, the Tea Hub concept is an initiative to import cheap Black Tea to Sri Lanka, for blending with our tea and for re-export thereafter. The component of cheap, imported tea in the blend, would reduce the cost of the resulting export and improve the profit margin of the local packer. This concept has a long history.

The cloud in the horizon

In 1979, the then Minister of Trade, the late Lalith Athulathmudali, visited the Rotterdam factory of Van Rees, a multinational trader. It was a centre for the bulking, blending, and packaging of cheap tea from multiple auction centres, sold thereafter in the Netherlands and various other European markets. Minister Athulathmudali, ignorant of the background realities of the local trade, had been deeply impressed by the scale of the Van Rees operation and, on his return, strongly advocated the setting up of a similar facility in Sri Lanka. When his views were made public, I vehemently objected to the proposal, giving reasons for my stance.

Athulathmudali was adamant but, fortunately, the then President, J. R. Jayewardene, summoned me, obtained my views, and immediately decided to shelve the idea. To the best of my recollection that was the first public airing of the Tea Hub concept. Since then, from time to time, the proposal has surfaced, on the initiative of traders who believe that selling Ceylon Tea cheap is the way forward.

I also recall that in late 1988, R. M. B. Senanayake, former civil servant and then General Manager of Jafferjee Brothers, in a newspaper article, suggested that whenever Ceylon Tea prices move up, exporters should be permitted to import cheaper tea for blending, in place of Tea. My reaction to it then was consternation, that a man who -lave known better should publicly advocate a policy with such potential for damage to the local tea industry.

New developments

On August 1, 2011, the trade members of the Tea Council of the Sri Lanka Tea Board, acting on behalf of the Tea Exporters’ Association submitted to the Tea Council of which I was then Chairman proposal to lift the existing restrictions on the importation of Orthodox Black Tea. Whilst as Chairman of the council I did not express my opinion on the matter, I refuted the proposal in my personal capacity as an exporter and in the larger interests of the tea industry the country.

In the many adverse opinions that were expressed regarding my position on this issue, and of my subsequent vocal and active opposition to the proposal, what was conveniently ignored by all my opponents was that liberalization of Black Tea imports would be greatly advantageous to my own label, ‘Dilmah’. With the global outreach of that brand and the marketing and distribution network which reinforced its overseas sales in over 100 countries, I stood to gain more than any other local exporter by the liberalization of Black Tea importation.

The provision to import specialty tea, not traditionally manufactured locally, is permitted by statute. If I recall rightly, such importation was first permitted in 1981 and the relevant conditions revised in 1994. The 1981 provision was withdrawn when Montague Jayawickrema, then Minister of Plantations, on a visit to Egypt with a trade delegation, ascertained for himself that exporters had been blending cheap Chinese tea with Ceylon Tea in order to reduce the blend cost and were providing the Egyptian market with a very low quality product, which was being perceived by the consumer as Ceylon Tea.

Ironically, that is a perfect example of the proposed methodology of the Tea Hub and, also, its likely outcome. There is no argument against the limited facilities available to the serious exporter for the importation of specialty tea such Darjeeling, select Assams, or other non-traditional varieties, not normally produced in this country. It is a legitimate and acceptable strategy used by exporters to widen their export product portfolio. Such teas are, invariably, far more costly on an average than Ceylon Tea and the Government permits imports of such varieties without restriction.

The annual importation of specialty tea is around five million kg per year, equivalent to two percent of the average annual Black Tea production of Sri Lanka, and is a volume which has no impact on the local industry. A Tea Hub is of immense attraction to the multinational trader or the local exporter, who packs on his behalf. It will enable the former to source his product at low cost, with zero investment in infrastructure, as that will be provided by his local servant at the latter’s cost.

Foreign label owners have no loyalty, either to the country of operation, the operation itself, or even to the consumer. He is motivated entirely by the bottom line and when appropriate, he will move out to another location which is able to serve his needs at a lower cost. This is an inevitable progression and can be illustrated with real-life examples.

Flawed logic

In their support of the Tea Hub proposal, the TEA submitted a wide range of arguments, all virtuously clothed to project an image of potential advantages to the local tea industry, when the actual intent was simply lowering the cost of their export blend.

One of the major planks of the TEA platform has been the totally unsupported premise, that the Tea Hub would soon result in growing the present annual export value of Ceylon Tea, from USD 1.2 billion to USD 5 billion. This hypothesis was never supported by either strategy, complementing arithmetic, or a financially-verifiable equation, and still remains a pathetic piece of wishful thinking. One of their primary concerns is that the high value of Ceylon Tea is an impediment to the servicing of international markets, and that the local opponents of the concept should not be apprehensive, that importation of cheap tea would devalue equivalent grades at the Colombo Auction.

Such arguments defy the simplest concepts of product supply, demand, and price dynamics, and do not merit an elaborate rebuttal. The Tea Hub proposal is based on plain self-delusion, garnished by unverifiable and statistically-unsupportable assumptions. A favourite theory of many economists and marketing consultants with absolutely no practical knowledge of the local tea industry in its totality is based on the feeble assumption that Sri Lankans are not capable of building brands and, therefore, the best option is to reduce Pure Ceylon Tea to the status of a commodity, or a raw material, for branding and value addition elsewhere.

Annually, we produce around 300 million kg of tea and sell all of it at the Colombo Auction, at the highest average price of any auction centre. On an average, we are generally around USD 1 higher than the second highest auction centre, Nairobi. With their wide-ranging arguments for a Tea Hub, that is the real issue that its proponents wish to address; the relatively high auction price in Colombo. The trader who is exporting a cheap commodity at Rs. 500 – Rs. 600 per kg is unable to compete with the local entrepreneur who is exporting a genuine good quality Ceylon Tea, with value added, at Rs. 1,000 per kg or more.

Even the Tea Hub proponents agree that Pure Ceylon Tea is of the finest quality. It does not require marketing expertise to conclude that a product which justifiably claims to be the best in quality must then be marketed at a commensurate price. That is an argument which any consumer will accept. For instance, there there are markets for both `Plonk’ and for high quality wine, with a massive price differential between the two. The Unique Selling Point of the former is price, whilst that of the latter is quality, which is where quality Ceylon Tea belongs.

Another argument that the Tea Hub offers is the increase of export volume, through importation and re-export after blending. Judging the effectiveness of an export operation by volume alone is a serious mistake, as it distorts realities. What is relevant is not the volume and foreign exchange earned, but the contribution to actual value. Heavy exports of bulk tea and crudely-presented small packs, meant for cheap markets, bring little or no return to the exporter.

Those are simply services provided to the multinational trader, by the local packer, with marginal corresponding benefits to the country of production. Value addition to the home-grown product, in the country of origin, is the only strategy which will ensure that all those in the commercial chain, from the farmer to the exporter, reap equitable benefits.

Features

Recruiting academics to state universities – beset by archaic selection processes?

Time has, by and large, stood still in the business of academic staff recruitment to state universities. Qualifications have proliferated and evolved to be more interdisciplinary, but our selection processes and evaluation criteria are unchanged since at least the late 1990s. But before I delve into the problems, I will describe the existing processes and schemes of recruitment. The discussion is limited to UGC-governed state universities (and does not include recruitment to medical and engineering sectors) though the problems may be relevant to other higher education institutions (HEIs).

How recruitment happens currently in SL state universities

Academic ranks in Sri Lankan state universities can be divided into three tiers (subdivisions are not discussed).

* Lecturer (Probationary)

– recruited with a four-year undergraduate degree. A tiny step higher is the Lecturer (Unconfirmed), recruited with a postgraduate degree but no teaching experience.

* A Senior Lecturer can be recruited with certain postgraduate qualifications and some number of years of teaching and research.

* Above this is the professor (of four types), which can be left out of this discussion since only one of those (Chair Professor) is by application.

State universities cannot hire permanent academic staff as and when they wish. Prior to advertising a vacancy, approval to recruit is obtained through a mind-numbing and time-consuming process (months!) ending at the Department of Management Services. The call for applications must list all ranks up to Senior Lecturer. All eligible candidates for Probationary to Senior Lecturer are interviewed, e.g., if a Department wants someone with a doctoral degree, they must still advertise for and interview candidates for all ranks, not only candidates with a doctoral degree. In the evaluation criteria, the first degree is more important than the doctoral degree (more on this strange phenomenon later). All of this is only possible when universities are not under a ‘hiring freeze’, which governments declare regularly and generally lasts several years.

Problem type 1

– Archaic processes and evaluation criteria

Twenty-five years ago, as a probationary lecturer with a first degree, I was a typical hire. We would be recruited, work some years and obtain postgraduate degrees (ideally using the privilege of paid study leave to attend a reputed university in the first world). State universities are primarily undergraduate teaching spaces, and when doctoral degrees were scarce, hiring probationary lecturers may have been a practical solution. The path to a higher degree was through the academic job. Now, due to availability of candidates with postgraduate qualifications and the problems of retaining academics who find foreign postgraduate opportunities, preference for candidates applying with a postgraduate qualification is growing. The evaluation scheme, however, prioritises the first degree over the candidate’s postgraduate education. Were I to apply to a Faculty of Education, despite a PhD on language teaching and research in education, I may not even be interviewed since my undergraduate degree is not in education. The ‘first degree first’ phenomenon shows that universities essentially ignore the intellectual development of a person beyond their early twenties. It also ignores the breadth of disciplines and their overlap with other fields.

This can be helped (not solved) by a simple fix, which can also reduce brain drain: give precedence to the doctoral degree in the required field, regardless of the candidate’s first degree, effected by a UGC circular. The suggestion is not fool-proof. It is a first step, and offered with the understanding that any selection process, however well the evaluation criteria are articulated, will be beset by multiple issues, including that of bias. Like other Sri Lankan institutions, universities, too, have tribal tendencies, surfacing in the form of a preference for one’s own alumni. Nevertheless, there are other problems that are, arguably, more pressing as I discuss next. In relation to the evaluation criteria, a problem is the narrow interpretation of any regulation, e.g., deciding the degree’s suitability based on the title rather than considering courses in the transcript. Despite rhetoric promoting internationalising and inter-disciplinarity, decision-making administrative and academic bodies have very literal expectations of candidates’ qualifications, e.g., a candidate with knowledge of digital literacy should show this through the title of the degree!

Problem type 2 – The mess of badly regulated higher education

A direct consequence of the contemporary expansion of higher education is a large number of applicants with myriad qualifications. The diversity of degree programmes cited makes the responsibility of selecting a suitable candidate for the job a challenging but very important one. After all, the job is for life – it is very difficult to fire a permanent employer in the state sector.

Widely varying undergraduate degree programmes.

At present, Sri Lankan undergraduates bring qualifications (at times more than one) from multiple types of higher education institutions: a degree from a UGC-affiliated state university, a state university external to the UGC, a state institution that is not a university, a foreign university, or a private HEI aka ‘private university’. It could be a degree received by attending on-site, in Sri Lanka or abroad. It could be from a private HEI’s affiliated foreign university or an external degree from a state university or an online only degree from a private HEI that is ‘UGC-approved’ or ‘Ministry of Education approved’, i.e., never studied in a university setting. Needless to say, the diversity (and their differences in quality) are dizzying. Unfortunately, under the evaluation scheme all degrees ‘recognised’ by the UGC are assigned the same marks. The same goes for the candidates’ merits or distinctions, first classes, etc., regardless of how difficult or easy the degree programme may be and even when capabilities, exposure, input, etc are obviously different.

Similar issues are faced when we consider postgraduate qualifications, though to a lesser degree. In my discipline(s), at least, a postgraduate degree obtained on-site from a first-world university is preferable to one from a local university (which usually have weekend or evening classes similar to part-time study) or online from a foreign university. Elitist this may be, but even the best local postgraduate degrees cannot provide the experience and intellectual growth gained by being in a university that gives you access to six million books and teaching and supervision by internationally-recognised scholars. Unfortunately, in the evaluation schemes for recruitment, the worst postgraduate qualification you know of will receive the same marks as one from NUS, Harvard or Leiden.

The problem is clear but what about a solution?

Recruitment to state universities needs to change to meet contemporary needs. We need evaluation criteria that allows us to get rid of the dross as well as a more sophisticated institutional understanding of using them. Recruitment is key if we want our institutions (and our country) to progress. I reiterate here the recommendations proposed in ‘Considerations for Higher Education Reform’ circulated previously by Kuppi Collective:

* Change bond regulations to be more just, in order to retain better qualified academics.

* Update the schemes of recruitment to reflect present-day realities of inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary training in order to recruit suitably qualified candidates.

* Ensure recruitment processes are made transparent by university administrations.

Kaushalya Perera is a senior lecturer at the University of Colombo.

(Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.)

Features

Talento … oozing with talent

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

Last week we had MISTER Band in our scene, and on 10th February, Yellow Beatz – both social media favourites.

Talento is a seven-piece band that plays all types of music, from the ‘60s to the modern tracks of today.

The band has reached many heights, since its inception in 2012, and has gained recognition as a leading wedding and dance band in the scene here.

The members that makeup the outfit have a solid musical background, which comes through years of hard work and dedication

Their portfolio of music contains a mix of both western and eastern songs and are carefully selected, they say, to match the requirements of the intended audience, occasion, or event.

Although the baila is a specialty, which is inherent to this group, that originates from Moratuwa, their repertoire is made up of a vast collection of love, classic, oldies and modern-day hits.

The musicians, who make up Talento, are:

Prabuddha Geetharuchi:

(Vocalist/ Frontman). He is an avid music enthusiast and was mentored by a lot of famous musicians, and trainers, since he was a child. Growing up with them influenced him to take on western songs, as well as other music styles. A Peterite, he is the main man behind the band Talento and is a versatile singer/entertainer who never fails to get the crowd going.

Geilee Fonseka (Vocals):

A dynamic and charismatic vocalist whose vibrant stage presence, and powerful voice, bring a fresh spark to every performance. Young, energetic, and musically refined, she is an artiste who effortlessly blends passion with precision – captivating audiences from the very first note. Blessed with an immense vocal range, Geilee is a truly versatile singer, confidently delivering Western and Eastern music across multiple languages and genres.

Chandana Perera (Drummer):

His expertise and exceptional skills have earned him recognition as one of the finest acoustic drummers in Sri Lanka. With over 40 tours under his belt, Chandana has demonstrated his dedication and passion for music, embodying the essential role of a drummer as the heartbeat of any band.

Harsha Soysa:

(Bassist/Vocalist). He a chorister of the western choir of St. Sebastian’s College, Moratuwa, who began his musical education under famous voice trainers, as well as bass guitar trainers in Sri Lanka. He has also performed at events overseas. He acts as the second singer of the band

Udara Jayakody:

(Keyboardist). He is also a qualified pianist, adding technical flavour to Talento’s music. His singing and harmonising skills are an extra asset to the band. From his childhood he has been a part of a number of orchestras as a pianist. He has also previously performed with several famous western bands.

Aruna Madushanka:

(Saxophonist). His proficiciency in playing various instruments, including the saxophone, soprano saxophone, and western flute, showcases his versatility as a musician, and his musical repertoire is further enhanced by his remarkable singing ability.

Prashan Pramuditha:

(Lead guitar). He has the ability to play different styles, both oriental and western music, and he also creates unique tones and patterns with the guitar..

Features

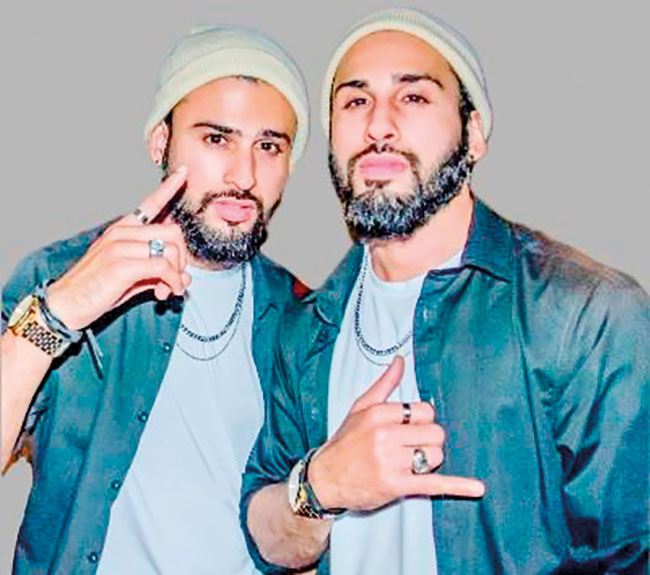

Special milestone for JJ Twins

The JJ Twins, the Sri Lankan musical duo, performing in the Maldives, and known for blending R&B, Hip Hop, and Sri Lankan rhythms, thereby creating a unique sound, have come out with a brand-new single ‘Me Mawathe.’

In fact, it’s a very special milestone for the twin brothers, Julian and Jason Prins, as ‘Me Mawathe’ is their first ever Sinhala song!

‘Me Mawathe’ showcases a fresh new sound, while staying true to the signature harmony and emotion that their fans love.

This heartfelt track captures the beauty of love, journey, and connection, brought to life through powerful vocals and captivating melodies.

It marks an exciting new chapter for the JJ Twins as they expand their musical journey and connect with audiences in a whole new way.

Their recent album, ‘CONCLUDED,’ explores themes of love, heartbreak, and healing, and include hits like ‘Can’t Get You Off My Mind’ and ‘You Left Me Here to Die’ which showcase their emotional intensity.

Readers could stay connected and follow JJ Twins on social media for exclusive updates, behind-the-scenes moments, and upcoming releases:

Instagram: http://instagram.com/jjtwinsofficial

TikTok: http://tiktok.com/@jjtwinsmusic

Facebook: http://facebook.com/jjtwinssingers

YouTube: http://youtube.com/jjtwins

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoAn innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoRatmalana Airport: The Truth, The Whole Truth, And Nothing But The Truth

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoDialog partners with Xiaomi to introduce Redmi Note 15 5G Series in Sri Lanka

-

Features7 days ago

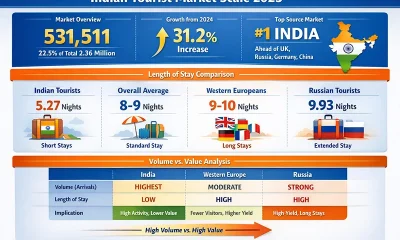

Features7 days agoBuilding on Sand: The Indian market trap

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days agoFuture must be won

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoBrilliant Navy officer no more

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoSri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans