Features

BARRIERS TO NATIONAL PROGRESS

The 107th birth anniversary of Professor J E Jayasuriya falls on 14 February 2025. To commemorate this event we publish the text of the address he delivered at the sixth graduation ceremony of the Institute of Social Work in December 1960 on ‘Barriers to National Progress’. Most of what he mentioned 65 years ago seem to be still relevant today and several things he predicted then have come true.

The 34th J E Jayasuriya Memorial Oration would be delivered by Professor Panduka Karunanayake, Professor, Department of Clinical Medicine, University of Colombo on ‘Revisiting Humanism in Education: Insights from Tagore’ at the Sri Lanka Foundation Institute on 14 February 2025 at 5 15 p.m.

by Professor J. E. Jayasuriya

by Professor J. E. Jayasuriya

Professor of Education, University of Ceylon

I have chosen for my address at this the sixth graduation ceremony of the Institute of Social Work the subject “Barriers to National Progress”. I consider it as being of vital importance at this juncture in our national development that we give some thought and consideration to the factors that appear to act as barriers to national progress. I propose to confine myself largely to the factors in the human situation. Indeed, I believe that the malaise in our society is largely, if not wholly, explainable in social terms, that the causes that hold us back from the path of national progress are located in our thoughts, our attitudes and our ideals, both individually and collectively, rather than outside us in some aspect of our geographical environment.

Social attitudes engendered by colonial rule

A country that has only recently emerged from colonial rule starts with quite crippling handicaps. Some of these have to do with the economy of the country but they are not my concern now. I am more concerned with the social attitudes engendered by colonial rule. In fairness to the British rulers, I may say straightaway that of the colonial rulers of the past the British were about the most liberal; but colonial rule, even by the most liberal of rulers, is not the best thing for a nation. Its psychological consequences could be more far reaching than its economic consequences.

The lack of an identity of interest between the common man and the government, the belief in the mind of the common man that the government is an institution removed from him and his interests and designed to keep him in serfdom, the pukka sahib mentality of officials, both high and low, who look upon themselves as the natural successors to the British rulers rather than as the servants of the local public, the great language barrier to communication, a barrier which is being removed only now, western ideals alien to the local culture pattern – these are some of the derivatives of colonial rule on the psychological plane and they have slowly and insidiously eaten into the body politic. It is only by bringing out some of these to the surface, examining them in their role as barriers to national progress, that we can perhaps hope to eradicate them.

The lack of a civic sense

One of the most perturbing of the social phenomena that would seem to be widely prevalent in our country is the lack of a civic sense. This manifests itself in various ways. Public property is nobody’s concern and it may be disfigured with impunity- as, for example, has happened to the walls of public buildings or desks in schools and in the University – or dismantled and removed without compunction -as, for example, has happened to the equipment in public telephone booths. There is little awareness that public property belongs to and has been paid for by the entire public, that a responsibility rests on every member of the public to safe-guard and protect public property, that repair of damage or replacement of losses would entail expenditure out of public funds, draining away money which might have been channeled to productive purposes with resulting improvements in living standards all round.

There is also a whole gamut of offences of a different sort against the public. They are of a white collar type (committed not by people in poor socio economic conditions as is perhaps the case with most offences against public buildings or appurtenances) and range from making false tax returns, submitting false travelling claims, certifying for a consideration shoddy work that is not up to the required standard (witness, for example, public buildings that show cracks after completion by private contractors) and the net result of these offences is a drain on the country’s financial resources.

One of the most dangerous features about this kind of offence is the absence of a feeling of guilt on the part of the offender. Many who would shudder at the thought of thieving from a private individual would nevertheless regard state funds as fair prey. Some have even developed such skill in these arts and crafts that they are quite openly prepared to place their specialized knowledge at the disposal of others and initiate them into the most successful techniques for defrauding the state. Quite clearly, even in the highest of circles there often appear to be two standards of morality, one governing private life and impeccable on the financial plane, the other governing public life and not averse to regarding public coffers as legitimate prey. This surely is a situation that must cause concern among all those who have the interest of the country at heart and one that is deserving of close study by social scientists.

Behaviour of the typical public servant

An attitude that is characterized by less moral taint perhaps but with equally damaging consequences to the public exchequer is reflected in the behaviour of the typical public servant. How few in the public service have a sense of duty that would stand a search by their own consciences! – Is it not a fact that the numerical strength of almost every department in the public service is far in excess of real needs? Quite apart from the fact that the rising salary bill in respect of the public services consumes money that could with advantage be utilized for economic development, there is also the wastage of human resources involved in employing in unproductive work a large work force that could be engaged in productive or creative work. It is all too easy for departmental heads to ask for more and more staff without taking the steps necessary for any scientific assessment of requirements. There is a very great need for an operational research unit that could go into the working of government departments, sample the daily quota of work of the employees and assess the strength of the staff really necessary for its purposes.

Uneconomic use of man hours

It is not only at the subordinate level that there is wastage of human resources. The uneconomic use of man hours at the top level is another problem that faces us. Tremendous tasks, essential for national reconstruction and requiring concentrated study, thinking, planning and execution lie ahead of those in high places Ministers, Heads of Departments and the like – and yet activities like the opening of a bridge, laying the foundation stone for a school building do every day take high officials several dozen miles away from their offices with several hours absence from their work. Are not large and significant issues often neglected in the rush for time consequent on this preoccupation with ceremonial trifles? This is not to deny the public relations aspect of the work of high officials. It is indeed a very important aspect but it must be undertaken with a due sense of proportion and organized in such a way that waste is minimized by setting apart a few days every month for such visits and perhaps having a programme at a number of places in a limited geographical area on such visits rather than visiting Kandy the first day, Badulla the second day, Batticaloa the third day, Jaffna the fourth day, back to office on the fifth day, to repeat the course again in a few days.

Lack of effective channels of communication

Lack of effective channels of communication is another problem that faces us, and one which is often responsible for the best results not being achieved whatever the activity or enterprise concerned. Communication in this country is usually a one-way process of transmitting instructions and orders from above to those below. But the reverse process of communication, from those down below to those above detailing their views and their perceptions of the same problem, and possibly these may be quite down-to-earth observations of real value, is discouraged and even regarded as evidence of objectionable rudeness. It is not realized sufficiently that no one ever lost by an exchange of views, and that a great deal of light is likely to be thrown on a problem when a number of persons collectively examine it, bringing to bear on it their several insights. In this connection, it must be remembered that discussion in its most profitable form does not come from a mass conference but when small groups meet and a real exchange of views takes place. The views of several such groups may be collected and the product in most cases would be illuminating beyond expectation.

Not even the most carefully thought-out plans work quite according to schedule. In their implementation, practical difficulties arise, and these are best seen not by the top-level planners but by the humble folk down the line who have to execute the details of the plans. Take, for example, the Guaranteed Price Scheme for paddy or the Paddy Lands Act. Field staff know best the defects, shortcomings, and loopholes in each. Collectively, they possess those insights that can remedy existing weaknesses in administering them, but they are not given opportunities to communicate their views. Indeed, if one of them were to suggest desirable modifications, that would be regarded as an act of sacrilege. Little wonder then, that they choose the path of least discomfort and let things just drift along. The reluctance to invite the views of those below us in the administrative hierarchy is part of the pukka sahib mentality of colonial administrators and we must get out of it if we are to prosper as a nation.

Talent of local experts

We have also to have faith in our fellow citizens and realize that the specialist knowledge required for national development in most spheres of work is possessed by one or more of them and that we ought not look slavishly for saviours from outside. Nothing has been found more frustrating by many gifted individuals in this country than to have some foreign expert enthroned above their heads, every word from whose lips is reverentially received, and nothing which anyone here said or could say counted at all against his counsel. I am not suggesting that we should do away entirely with foreign experts but let us have a due sense of proportion in accepting what they say. Let us, above all, examine their credentials carefully before we invite them. Some of the so-called experts we get have not solved problems in any other part of the world and in some cases have been unable to get decent employment in their own country.

It is because of this dependence on foreign experts that we have not up to this day mobilized the scientists of this country and sought their advice in connection with national development. Almost every other country in the world regards its scientists as a priceless treasure and their specialized knowledge is fully utilized in planning national development. In this country, we have recently given some recognition to economists, but they are not surely in possession of the whole truth. What about our physical and biological scientists, our agricultural scientists and engineers? What recognition do we give them? What opportunity do we give them to help us in finding solutions to our national problems? Every year, at the annual sessions of the Ceylon Association for the Advancement of Science, a number of research papers are read by them, suggestive for the task of finding solutions to many national problems, but what notice is taken of these? Whether it be increasing rice yields, developing inland fisheries, expansion of cottage industries, flood protection schemes, assessing the manpower required for national development—in fact, almost every national problem that we can think of has at some time or other received the attention of one or more members of the Association.

Given the opportunity, they are only too willing to place their insights at the disposal of the government, and it is time that action was taken to mobilize the scientific manpower of the country in a concentrated attack on the problems that confront us. I have not referred to social scientists other than the economist but their role, particularly that of the psychologist, is a vital one. Upon the psychologist must fall the task of discovering the genesis of harmful social attitudes and inducing change in the right direction. On him falls also the task of discovering the processes of social engineering that must accompany change in other spheres.

The human relations aspect of planning plays a key role in determining the success of any plan. Be it a colonization scheme, be it a plan for making farmers take to modern methods of agriculture, be it an attempt to educate people in healthy living, be it a plan to encourage the co-operative movement – all these involve a human relations aspect pivotal to success. Indeed, the experience of failure in the past in some of these was due in no small measure to neglect of the human relations aspect. Management techniques enjoy a high priority in the private sector, but their importance is not realized in the government sector. We have no school for administrators where, inter alia, they might be schooled in the dynamics of human behaviour so that they would know how to get on with people, win their confidence and enlist their co-operation, induce them to change their behaviour in desired directions and generally influence them.

Dealing with people is one of the hardest tasks possible and yet there is no awareness of the intricacies of the problem. Village upliftment should be one of the top priorities in any plan for national progress, and I know that it is a problem to which the Honourable Minister present here today is devoting a great deal of attention. So much depends on the proper training of the personnel to be employed in this task, and it would be suicidal not to give the most careful attention to the problem of providing comprehensive training courses for them. In the field of training for social work, this Institute deserves the thanks of the country for having filled a vacuum when the government itself was unwilling to move. It cannot, however, perpetually depend on charity and benefactions, and it seems to me that the time has now come for the State to recognize its work in a big way and perhaps attach it to one of the Universities.

The parlous state of the finances of the country

One last point. What awareness is there among us of the fact that the country is going through a very critical period from the point of view of the finances of the country? I am quite certain that the parlous state of the finances of the country has not caused any concern to us or given us any sense of urgency. We continue to ask for more and more in terms of wages and salaries. We continue to import more and more of the choicest luxury goods. Unconcernedly we try to live Rolls Royce lives on a bullock cart economy. Times of great financial stress have not been unknown in the history of nations, nations much more advanced than we are. For some three or four years after the last war, Britain went through a period of great financial stress. There were austerity drives that touched the lives of the people at all points. Foodstuffs like eggs and bacon were on ration during these years. Foreign exchange for travel was severely restricted. But there was a remarkable oneness of purpose in the government and the people. The people faced discomfort with fortitude and showed deep faith that given their wholehearted co-operation the government would pull through and steer them to plenty again.

As finances improved, restrictions were progressively relaxed and in the year 1959 the government was able to exclaim from roof tops that Britain had never been so prosperous before as in that year. Nearer home, India sets us something of an example in plain living. The lives of Gandhi in his day and of Vinobha Bhave in the present day have fired the imagination of the people. The people of this country cannot be insensitive to high ideals or to the call of the nation, but we seem to be in such a state of stupor that only a personality of extraordinary dynamism, reflecting in his or her life a spirit of selfless service and the greatness of simplicity and high purpose, can rouse our people to meet the challenge that faces us. In the meantime, perhaps some little good may come if lesser mortals like you and me ponder over these issues, and it is with this hope that I have placed them before you.

(Originally published in the Ceylon Journal of Social Work vol. 2, no. 2, 1961.)

Features

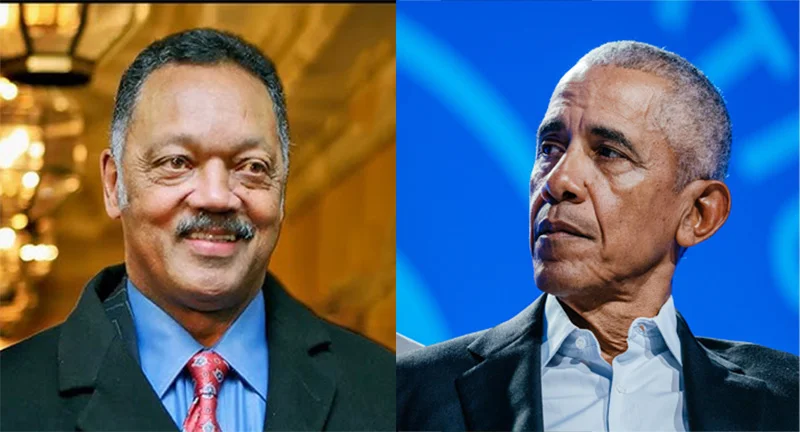

How Black Civil Rights leaders strengthen democracy in the US

On being elected US President in 2008, Barack Obama famously stated: ‘Change has come to America’. Considering the questions continuing to grow out of the status of minority rights in particular in the US, this declaration by the former US President could come to be seen as somewhat premature by some. However, there could be no doubt that the election of Barack Obama to the US presidency proved that democracy in the US is to a considerable degree inclusive and accommodating.

On being elected US President in 2008, Barack Obama famously stated: ‘Change has come to America’. Considering the questions continuing to grow out of the status of minority rights in particular in the US, this declaration by the former US President could come to be seen as somewhat premature by some. However, there could be no doubt that the election of Barack Obama to the US presidency proved that democracy in the US is to a considerable degree inclusive and accommodating.

If this were not so, Barack Obama, an Afro-American politician, would never have been elected President of the US. Obama was exceptionally capable, charismatic and eloquent but these qualities alone could not have paved the way for his victory. On careful reflection it could be said that the solid groundwork laid by indefatigable Black Civil Rights activists in the US of the likes of Martin Luther King (Jnr) and Jesse Jackson, who passed away just recently, went a great distance to enable Obama to come to power and that too for two terms. Obama is on record as owning to the profound influence these Civil Rights leaders had on his career.

The fact is that these Civil Rights activists and Obama himself spoke to the hearts and minds of most Americans and convinced them of the need for democratic inclusion in the US. They, in other words, made a convincing case for Black rights. Above all, their struggles were largely peaceful.

Their reasoning resonated well with the thinking sections of the US who saw them as subscribers to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, for instance, which made a lucid case for mankind’s equal dignity. That is, ‘all human beings are equal in dignity.’

It may be recalled that Martin Luther King (Jnr.) famously declared: ‘I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up, live out the true meaning of its creed….We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’

Jesse Jackson vied unsuccessfully to be a Democratic Party presidential candidate twice but his energetic campaigns helped to raise public awareness about the injustices and material hardships suffered by the black community in particular. Obama, we now know, worked hard at grass roots level in the run-up to his election. This experience proved invaluable in his efforts to sensitize the public to the harsh realities of the depressed sections of US society.

Cynics are bound to retort on reading the foregoing that all the good work done by the political personalities in question has come to nought in the US; currently administered by Republican hard line President Donald Trump. Needless to say, minority communities are now no longer welcome in the US and migrants are coming to be seen as virtual outcasts who need to be ‘shown the door’ . All this seems to be happening in so short a while since the Democrats were voted out of office at the last presidential election.

However, the last US presidential election was not free of controversy and the lesson is far too easily forgotten that democratic development is a process that needs to be persisted with. In a vital sense it is ‘a journey’ that encounters huge ups and downs. More so why it must be judiciously steered and in the absence of such foresighted managing the democratic process could very well run aground and this misfortune is overtaking the US to a notable extent.

The onus is on the Democratic Party and other sections supportive of democracy to halt the US’ steady slide into authoritarianism and white supremacist rule. They would need to demonstrate the foresight, dexterity and resourcefulness of the Black leaders in focus. In the absence of such dynamic political activism, the steady decline of the US as a major democracy cannot be prevented.

From the foregoing some important foreign policy issues crop-up for the global South in particular. The US’ prowess as the ‘world’s mightiest democracy’ could be called in question at present but none could doubt the flexibility of its governance system. The system’s inclusivity and accommodative nature remains and the possibility could not be ruled out of the system throwing up another leader of the stature of Barack Obama who could to a great extent rally the US public behind him in the direction of democratic development. In the event of the latter happening, the US could come to experience a democratic rejuvenation.

The latter possibilities need to be borne in mind by politicians of the South in particular. The latter have come to inherit a legacy of Non-alignment and this will stand them in good stead; particularly if their countries are bankrupt and helpless, as is Sri Lanka’s lot currently. They cannot afford to take sides rigorously in the foreign relations sphere but Non-alignment should not come to mean for them an unreserved alliance with the major powers of the South, such as China. Nor could they come under the dictates of Russia. For, both these major powers that have been deferentially treated by the South over the decades are essentially authoritarian in nature and a blind tie-up with them would not be in the best interests of the South, going forward.

However, while the South should not ruffle its ties with the big powers of the South it would need to ensure that its ties with the democracies of the West in particular remain intact in a flourishing condition. This is what Non-alignment, correctly understood, advises.

Accordingly, considering the US’ democratic resilience and its intrinsic strengths, the South would do well to be on cordial terms with the US as well. A Black presidency in the US has after all proved that the US is not predestined, so to speak, to be a country for only the jingoistic whites. It could genuinely be an all-inclusive, accommodative democracy and by virtue of these characteristics could be an inspiration for the South.

However, political leaders of the South would need to consider their development options very judiciously. The ‘neo-liberal’ ideology of the West need not necessarily be adopted but central planning and equity could be brought to the forefront of their talks with Western financial institutions. Dexterity in diplomacy would prove vital.

Features

Grown: Rich remnants from two countries

Whispers of Lanka

I was born in a hamlet on the western edge of a tiny teacup bay named Mirissa on the South Coast of Sri Lanka. My childhood was very happy and secure. I played with my cousins and friends on the dusty village roads. We had a few toys to play with, so we always improvised our own games. On rainy days, the village roads became small rivulets on which we sailed paper boats. We could walk from someone’s backyard to another, and there were no fences. We had the freedom to explore the surrounding hills, valleys, and streams.

I was good at school and often helped my classmates with their lessons. I passed the General Certificate of Education (Ordinary Level) at the village school and went to Colombo to study for the General Certificate of Education (Advanced Level). However, I did not like Colombo, and every weekend I hurried back to the village. I was not particularly interested in my studies and struggled in specific subjects. But my teachers knew that I was intelligent and encouraged me to study hard.

To my amazement, I passed the Advanced Level, entered the University of Kelaniya, completed an honours degree in Economics, taught for a few months at a central college, became a lecturer at the same university, and later joined the Department of Census and Statistics as a statistician. Then I went to the University of Wales in the UK to study for an MSc.

The interactions with other international students in my study group, along with very positive recommendations from my professors, helped me secure several jobs in the oil-rich Middle Eastern countries, where I earned salaries unimaginable in Sri Lankan terms. During this period, without much thought, I entered a life focused on material possessions, social status, and excessive consumerism.

Life changes

Unfortunately, this comfortable, enjoyable life changed drastically in the mid-1980s because of the political activities of certain groups. Radicalised youths, brainwashed and empowered by the dynamics of vibrant leftist politics, killed political opponents as well as ordinary people who were reluctant to follow their orders. Their violent methods frightened a large section of Sri Lanka’s middle class into reluctantly accepting country-wide closures of schools, factories, businesses, and government offices.

My father’s generation felt a deep obligation to honour the sacrifices they had made to give us everything we had. There was a belief that you made it in life through your education, and that if you had to work hard, you did. Although I had never seriously considered emigration before, our sons’ education was paramount, and we left Sri Lanka.

Although there were regulations on what could be brought in, migrating to Sydney in the 1980s offered a more relaxed airport experience, with simpler security, a strong presence of airline staff, and a more formal atmosphere. As we were relocating permanently, a few weeks before our departure, we had organised a container to transport sentimental belongings from our home. Our flight baggage was minimal, which puzzled the customs officer, but he laughed when he saw another bulky item on a separate trolley. It was a large box containing a bookshelf purchased in Singapore. Upon discovering that a new migrant family was arriving in Australia with a 32-volume Encyclopaedia Britannica set weighing approximately 250 kilograms, he became cheerful, relaxed his jaw, and said, G’day!

Settling in Sydney

We settled in Epping, Sydney, and enrolled our sons in Epping Boys’ High School. Within one week of our arrival from Sri Lanka, we both found jobs: my wife in her usual accounting position in the private sector, and I was taken on by the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA). While working at the CAA, I sat the Australian Graduate Admission Test. I secured a graduate position with the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) in Canberra, ACT.

We bought a house in Florey, close to my office in Belconnen. The roads near the house were eerily quiet. Back in my hometown of Pelawatta, outside Colombo, my life had a distinct soundtrack. I woke up every morning to the radios blasting ‘pirith’ from the nearby houses; the music of the bread delivery van announcing its arrival, an old man was muttering wild curses to someone while setting up his thambili cart near the junction, free-ranging ‘pariah’ dogs were barking at every moving thing and shadows. Even the wildlife was noisy- black crows gathered on the branches of the mango tree in front of the house to perform a mournful dirge in the morning.

Our Australian neighbours gave us good advice and guidance, and we gradually settled in. If one of the complaints about Asians is that they “won’t join in or integrate to the same degree as Australians do,” this did not apply to us! We never attempted to become Aussies; that was impossible because we didn’t have tanned skin, hazel eyes, or blonde hair, but we did join in the Australian way of life. Having a beer with my next-door neighbour on the weekend and a biannual get-together with the residents of the lane became a routine. Walking or cycling ten kilometres around the Ginninderra Lake with a fit-fanatic of a neighbour was a weekly ritual that I rarely skipped.

Almost every year, early in the New Year, we went to the South Coast. My family and two of our best friends shared a rented house near the beach for a week. There’s not much to do except mix with lots of families with kids, dogs on the beach, lazy days in the sun with a barbecue and a couple of beers in the evening, watching golden sunsets. When you think about Australian summer holidays, that’s all you really need, and that’s all we had!

Caught between two cultures

We tried to hold on to our national tradition of warm hospitality by organising weekend meals with our friends. Enticed by the promise of my wife’s home-cooked feast, our Sri Lankan friends would congregate at our place. Each family would also bring a special dish of food to share. Our house would be crammed with my friends, their spouses and children, the sound of laughter and loud chatter – English mingled with Sinhala – and the aroma of spicy food.

We loved the togetherness, the feeling of never being alone, and the deep sense of belonging within the community. That doesn’t mean I had no regrets in my Australian lifestyle, no matter how trivial they may have seemed. I would have seen migration to another country only as a change of abode and employment, and I would rarely have expected it to bring about far greater changes to my psychological role and identity. In Sri Lanka, I have grown to maturity within a society with rigid demarcation lines between academic, professional, and other groups.

Furthermore, the transplantation from a patriarchal society where family bonds were essential to a culture where individual pursuit of happiness tended to undermine traditional values was a difficult one for me. While I struggled with my changing role, my sons quickly adopted the behaviour and aspirations of their Australian peers. A significant part of our sons’ challenges lay in their being the first generation of Sri Lankan-Australians.

The uniqueness of the responsibilities they discovered while growing up in Australia, and with their parents coming from another country, required them to play a linguistic mediator role, and we, as parents, had to play the cultural mediator role. They were more gregarious and adaptive than we were, and consequently, there was an instant, unrestrained immersion in cultural diversity and plurality.

Technology

They became articulate spokesmen for young Australians growing up in a world where information technology and transactions have become faster, more advanced, and much more widespread. My work in the ABS for nearly twenty years has followed cycles, from data collection, processing, quality assurance, and analysis to mapping, research, and publishing. As the work was mainly computer-based and required assessing and interrogating large datasets, I often had to depend heavily on in-house software developers and mainframe programmers. Over that time, I have worked in several areas of the ABS, making a valuable contribution and gaining a wide range of experience in national accounting.

I immensely valued the unbiased nature of my work, in which the ABS strived to inform its readers without the influence of public opinion or government decisions. It made me proud to work for an organisation that had a high regard for quality, accuracy, and confidentiality. I’m not exaggerating, but it is one of the world’s best statistical organisations! I rubbed shoulders with the greatest statistical minds. The value of this experience was that it enabled me to secure many assignments in Vanuatu, Fiji, East Timor, Saudi Arabia, and the Solomon Islands through the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund after I left the ABS.

Living in Australia

Studying and living in Australia gave my sons ample opportunities to realise that their success depended not on acquiring material wealth but on building human capital. They discovered that it was the sum total of their skills embodied within them: education, intelligence, creativity, work experience and even the ability to play basketball and cricket competitively. They knew it was what they would be left with if someone stripped away all of their assets. So they did their best to pursue their careers on that path and achieve their life goals. Of course, the healthy Australian economy mattered too. As an economist said, “A strong economy did not transform a valet parking attendant into a professor. Investment in human capital did that.”

Nostalgia

After living in Australia for several decades, do I miss Sri Lanka? Which country deserves my preference, the one where I was born or the one to which I migrated? There is no single answer; it depends on opportunities, prospects, lifestyle, and family. Factors such as the cost of living, healthcare, climate, and culture also play significant roles in shaping this preference. Tradition in a slow-motion place like Sri Lanka is an ethical code based on honouring those who do things the same way you do, and dishonour those who don’t. However, in Australia, one has the freedom to express oneself, to debate openly, to hold unconventional views, to be more immune to peer pressure, and not to have one’s every action scrutinised and discussed.

For many years, I have navigated the challenges of cultural differences, conflicting values, and the constant negotiation of where I truly ‘belong.’ Instead of yearning for a ‘dream home’ where I once lived, I have struggled, and to some extent succeeded, to find a home where I live now. This does not mean I have forgotten or discarded my roots. As one Sri Lankan-Australian senior executive remarked, “I have not restricted myself to the box I came in… I was not the ethnicity, skin colour, or lack thereof, of the typical Australian… but that has been irrelevant to my ability to contribute to the things which are important to me and to the country adopted by me.” Now, why do I live where I live – in that old house in Florey? I love the freshness of the air, away from the city smog, noisy traffic, and fumes. I enjoy walking in the evening along the tree-lined avenues and footpaths in my suburb, and occasionally I see a kangaroo hopping along the nature strip. I like the abundance of trees and birds singing at my back door. There are many species of birds in the area, but a common link with ours is the melodious warbling of resident magpies. My wife has been feeding them for several years, and we see the new fledglings every year. At first light and in the evening, they walk up to the back door and sing for their meal. The magpie is an Australian icon, and I think its singing is one of the most melodious sounds in the suburban areas and even more so in the bush.

by Siri Ipalawatte

Features

Big scene for models…

Modelling has turned out to be a big scene here and now there are lots of opportunities for girls and boys to excel as models.

Of course, one can’t step onto the ramp without proper training, and training should be in the hands of those who are aware of what modelling is all about.

Rukmal Senanayake is very much in the news these days and his Model With Ruki – Model Academy & Agency – is responsible for bringing into the limelight, not only upcoming models but also contestants participating in beauty pageants, especially internationally.

On the 29th of January, this year, it was a vibrant scene at the Temple Trees Auditorium, in Colombo, when Rukmal introduced the Grey Goose Road To Future Model Hunt.

Tharaka Gurukanda … in

the scene with Rukmal

This is the second Model Hunt to be held in Sri Lanka; the first was in 2023, at Nelum Pokuna, where over 150 models were able to showcase their skills at one of the largest fashion ramps in Sri Lanka.

The concept was created by Rukmal Senanayake and co-founded by Tharaka Gurukanda.

Future Model Hunt, is the only Southeast Asian fashion show for upcoming models, and designers, to work along and create a career for their future.

The Grey Goose Road To Future Model Hunt, which showcased two segments, brought into the limelight several models, including students of Ruki’s Model Academy & Agency and those who are established as models.

An enthusiastic audience was kept spellbound by the happenings on the ramp.

Doing it differently

Four candidates were also crowned, at this prestigious event, and they will represent Sri Lanka at the respective international pageants.

Those who missed the Grey Goose Road To Future Model Hunt, held last month, can look forward to another exciting Future Model Hunt event, scheduled for the month of May, 2026, where, I’m told, over 150 models will walk the ramp, along with several designers.

It will be held at a prime location in Colombo with an audience count, expected to be over 2000.

Model With Ruki offers training for ramp modelling and beauty pageants and other professional modelling areas.

Their courses cover: Ramp walk techniques, Posture and grooming, Pose and expression, Runway etiquette, and Photo shoots and portfolio building,

They prepare models for local and international fashion events, shoots, and competitions and even send models abroad for various promotional events.

-

Life style5 days ago

Life style5 days agoMarriot new GM Suranga

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoMonks’ march, in America and Sri Lanka

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoThe Rise of Takaichi

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoWetlands of Sri Lanka:

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoThailand to recruit 10,000 Lankans under new labour pact

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoMassive Sangha confab to address alleged injustices against monks

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoIMF MD here