Midweek Review

An epic history of reason

Brecht’s Life of Galileo:

By Laleen Jayamanne

Andrea: Unhappy the land

hat breeds no hero.

Galileo: No! Unhappy the land

that needs a hero.

Brecht in Sri Lanka

It is interesting that while three of Brecht’s plays were translated into Sinhala and successfully performed, The Life of Galileo (as far as I know), has not been translated. It was directed by Percy Colin-Thomé in English, with the Aquinas University College theatre workshop, in 1969. A Professor of Physics, Arthur Weerakoon, played Galileo with unabiding interest. The unusual back projections of text and the lively Italian Carnevale scene are still vivid in my memory. I remember revellers in masks and a figure dressed as the sun around which a child dressed as green earth, danced to the cheers of the crowd who well understood what the skit meant. The telescope, an invention Galileo modified and trained on the stars, was sold cheaply as an optical toy in the city streets. The Carnevale scene showed that the astronomer Galileo Galilei’s momentous discovery that the earth moved around the sun had reached the marketplace. Popular pamphlets about it were distributed, songs sung. A new age, they thought, had arrived.

I am now wondering why this play about the struggle between scientific reason, ethics, religious myth and superstition promoted by the all-powerful Catholic Church, failed to interest progressive Sinhala theatre folk of the 1960s. Might it interest Lankan theatre folk and students now, as they struggle to grapple with the current political, economic and ethical turmoil in the country and the role an ethnoreligious state ideology plays in it?

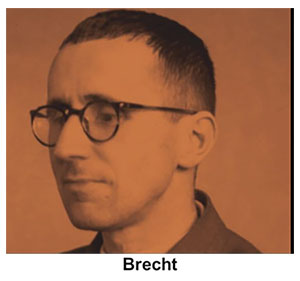

The Second World War – 1939

Brecht wrote his four major Epic plays in exile in Denmark and the US, after he fled Germany when Hitler came to power in 1933. The first of these was The Life of Galileo written in three weeks in late 1938 in Denmark where Niels Bohr was working on the problem of splitting the atom. Unlike his other plays, which were based on parables, Galileo was based on a famous historical figure. Bohr’s assistants advised Brecht on Ptolemaic cosmology which presented the universe as a ‘crystal sphere.’ A model of it became an important prop in the play. It is this ancient static model of the universe (accepted by the church of Rome), which Galileo challenged with his dynamic theory of a heliocentric universe. The history of writing, translating and revising the play is linked to major world historical events. In 1940 when Hitler invaded Denmark, Brecht and family escaped, via Finland, Moscow and Vladivostok to California.

Hiroshima – 6 August 1945

Later, while Brecht worked on the play with the brilliant English actor Charles Laughton in LA in 1945, the US dropped the atom bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In his diary Brecht writes of the horror and mourning expressed by ordinary Americans on the streets, though it meant the end of the war and return of their husbands and sons, victorious. Brecht’s play, which shows the birth of the ‘New Scientific Age’, carried a dark premonition. It also demonstrated the way Galileo betrayed his own rational discovery, by recanting his ideas so as to escape torture and death as a heretic.

Death of Stalin – 1953

After the war Brecht went to live in East Berlin under Soviet rule, where he created his famous Berliner Ensemble with his wife, the great Brechtian actress, Helena Weigel. Brecht reworked Galileo while living in East Berlin when Stalin died in 1953. He would have had a keen understanding of the Stalinist Soviet bureaucracy that ‘purged’ artistes, some of them close friends, including Tretyakov the playwright, who he considered his teacher. Born in 1898, Brecht died in 1956 relatively young, without being able to direct Galileo with his ensemble as he had planned.

After the war Brecht went to live in East Berlin under Soviet rule, where he created his famous Berliner Ensemble with his wife, the great Brechtian actress, Helena Weigel. Brecht reworked Galileo while living in East Berlin when Stalin died in 1953. He would have had a keen understanding of the Stalinist Soviet bureaucracy that ‘purged’ artistes, some of them close friends, including Tretyakov the playwright, who he considered his teacher. Born in 1898, Brecht died in 1956 relatively young, without being able to direct Galileo with his ensemble as he had planned.

The Holy Inquisition of Rome

The 17th Century papal court in Rome was a vast bureaucracy, which controlled knowledge, wealth and the people in a hierarchical pre-ordained structure, just as they imagined the universe to be. In fact Brecht referred to that Church, not entirely ironically, as a ‘secular institution’ in its comprehensive pursuit of power and policing of thought. Pope Urban VIII (who summoned Galileo to the Inquisition), was himself a mathematician. They agreed that Galileo’s math was correct but not the radical conclusions he drew from it, which contradicted church dogma of the earth’s centrality in the universe. Still, for the Church, Galileo alive (as the preeminent and famous astronomer and physicist of Europe) was more useful than burnt-alive as a heretic. This way Italian merchants could use his star charts to navigate the seas. If he was burnt as a heretic all of his knowledge would be proscribed, unable to be put to practical commercial use. The church was a political organisation that kept the peasantry in their impoverished place, as it was preordained in the Bible. Galileo, according to the play, did not join the new mercantile bourgeois class even when he had an opportunity to help form a resisting power block, but instead bowed to Church power and Princely feudal social relations through fear of physical torture.

Brecht in America

California is where a large number of German Jewish refugees went to flee Fascism, hoping to find work in the Hollywood film industry. Many of the highly trained technicians from the sophisticated German Weimar film industry did get employed, enriching Hollywood cinema, as did a few directors. But ironically, some of the Jewish actors had to play bit-roles as German Nazis in Hollywood anti-war films, because of their German accents and poor English! Charlie Chaplin befriended some of these artistes and was deeply concerned about what was happening in Europe, which is what prompted him to make The Great Dictator (1940).

In 1947 Brecht himself was called to appear at the Senate hearings of the House Un-American Activities Committee held against people suspected of being Communists. He left the States soon after. Chaplin, suspected of being a communist, was also called before this committee after he made Monsieur Verdoux (1947), when American audiences turned against him for playing the role of a benevolent murderer. When he requested a visa to leave and return to the US after a promotional tour to Europe, the State Dept. refused it. Then, quite astutely had his considerable wealth transferred to a Swiss bank and left the US for good. The most popular and loved star-director had become box-office and political ‘poison’ in an America driven by the anti-Communist witch-hunt. Many Hollywood directors, script-writers and actors lost their jobs either because they were or were suspected of being communists. Many progressive American artistes had joined the Communist Party during the 1930s Depression.

An Epic History of Reason

“June twenty-second sixteen thirty-three,

A momentous days for you and me,

Of all the days that was the one

An age of reason could have begun

“

The play explores how a ‘new age of reason’ became a ‘new dark age’ when the church suppressed the truth. The creation of scientific reason and ethics, and their accessibility to ordinary people, are major themes of the play. Brecht demonstrates how and why the authoritarian institution of the church controlled both the people and new knowledge. He does so through his newly formulated idea of epic theatre. He wanted theatre not only to be a place where emotions such as empathy and catharsis are experienced (as in the Greek tragedy), but also a forum for thought. He thought that epic devices such as a narrator or interruptions with song or projection of text and images would stimulate sensory thought.

Brecht’s Galileo was first performed in a small theatre in Los Angeles in 1947 with Charles Laughton in the lead and directed by Joseph Losey who had socialist sympathies and had also visited the Soviet Union in the 1930s. There is a very intricate account of their collaboration, in Brecht’s diary, gold for those interested in Brechtian acting and staging, and his thinking on the new Epic mode.

The play is about several aspects of the life of the great scientist. He is presented as a man who has a robust enjoyment of eating, drinking, teaching, observing, thinking and writing. The play opens with him enjoying his bath and talking about astronomy with his maid’s son, Andrea, who is only nine. He is teaching him the new astronomy that ‘the earth moves’ around the sun through a playful demonstration. The play concludes with Andrea (now a physicist himself), confronting his teacher.

Reason in Buddhist Philosophy

Within the history of Indian philosophy Buddhism offered an interrogation and understanding of the human mind, its processes of thinking and of reason. The Buddha rejected traditional Hindu ideas of animal sacrifice, elaborate priestly ritual and faith in revealed sacred texts. He promoted debate and introspective, yet detached examination of mental processes. He spoke to the people in the vernacular Pali, rather than in the language of learning and power, Sanskrit. But when the Buddha’s teaching became a popular religion over many centuries and received political patronage as in Sri Lanka, it became also a source of superstition and myths, used by rulers to propagate their authoritarian power.

Former President Mahinda Rajapaksa’s government created an ideology of the ‘war hero’ (ranawiru), in order to win the war against the LTTE. It was promoted as a war to save Lanka as an exclusive Sinhala-Buddhist nation, headed by a leader who was likened to the celebrated ancient King Dutugemunu who defeated the Tamil king Elara. Through this legend, reinforced by a genre of historical epic films, the heavy militarisation of an authoritarian ethno-religious state was normalised, consolidated and enthusiastically embraced by a large majority of Sinhala folk.

Tisaranee Gunasekara issues a timely warning in her article, Prelude to the Elections (GroundViews, 8/21/22). At first she gives a global historical perspective on religious violence.

“When Pope Francis visited Greece, a Greek Orthodox priest called him a heretic. That charge would have led to a gruesome death by fire in most of Europe just a few hundred years ago. If that past seems not just another time but another universe, it was thanks to the work of Christians who struggled for religious reforms and the secularisation of politics, often at the risk of their lives. It is the inadequacy of such struggles or their failure that creates spaces for fatwas against authors and their brutal implementation”.

Then she focuses on Sri Lanka’s recent ethno-religious politics and offers a reasonable suggestion for the next elections in the context of the ongoing Aragalaya.

“Religion and race played a decisive role in the 2019 and 2020 elections and here we are. Minimising these deadly influences is necessary to ensure that the next election produces a parliament that is more moderate and more rational […] the more moderate parties should form an understanding about not giving nominations to clergy of any religion and keeping religious symbols out of politics in general and electoral politics in particular.”

Galileo Betrays Science

Shown the instruments of torture, fearing death by fire, Galileo recants. He denies the scientific knowledge he arrived at by empirically studying the sky through a telescope for the very first time in history and through his mathematical calculations. Saved from death, he lives in relative comfort, under house arrest in Florence and writes his Discorsi in Italian rather than in Latin, the language of scholarship. While he dictated his book to his daughter, a monk would take away each page of the manuscript daily. But each night he would secretly make a copy and hide it inside a large globe!

Guru and Shishya

In the penultimate scene Galileo’s former student Andrea arrives (on route to Amsterdam to take up work as a physicist), to say farewell. The exchange between the great master and student who felt bitterly betrayed, is emotionally wrenching and crystal clear in conception. It is all of the following; a discourse, a debate, a lament, a lesson, on the betrayal of reason and of its consequences for humanity in the field of science. It is in every sense a brilliant ‘Epic Pedagogic Demonstration’ of what happens when reason is betrayed by unreason, and the irrational rules. Here, Brecht presents science (with its immense destructive modern technology and the atom bomb), as a matter of interest to all of humanity, not just to a clique of rulers and scientists. An epic articulation of this historical event is what is important here.

The full force of Galileo’s clear-eyed response to Andrea’s rebuke, ‘unhappy the land that breeds no hero,’ is felt here. When Andrea is ready to hail him as hero because Galileo has secretly completed the Discorsi, ‘the first important work of modern physics’, the master categorically refuses the exalted status even as he entrusts his manuscript to Andrea for safe delivery to an enlightened Europe. Galileo warns Andrea to be extra careful when he crosses Germany – as though it were now Europa 1940!

Then, Brecht’s Galileo delivers his infamous speech of self-disgust and trenchant critique in response to Andrea’s high praise:

Andrea: Science has only one commandment; contribution. And you have contributed more than any man for a hundred years.

Galileo: Have I? Then welcome to my gutter, dear colleague in science and brother in treason: I sold out, you are a buyer. The first sight of the book! His mouth watered and scoldings were drowned. Blessed be our bargaining, white-washing, death fearing community!”

Note the brilliant shift of pronouns, modes of address and use of idiomatic cliché as epic devices.

In recanting Galileo says he betrayed the people who believed that a new age had begun. He knew, he said, that for a short while he was as strong as the church and could have, as a single individual, challenged its immense power but didn’t. He was famous across Europe and scientists were awaiting his latest research. But he adds that no single man can do science, that it is a collective enterprise and should concern everyone. It’s this collective social mission of scientific reason and its capacity to alleviate suffering that he thought he had betrayed. The great secrecy of the process of creating the hydrogen bomb in the Manhattan Project and its links to the US military machine were events with great immediacy for Brecht when writing Galileo. Brecht’s Galileo telescopes 17th Century Enlightenment Reason and 20th Century Instrumental Reason; State Violence and Mass-Destruction.

Christian Witch Burning

The final scene focuses on Andrea who leaves an old and blind Galileo behind settling down to eat a roast goose for dinner. He has refused to give his sullied hand to Andrea who he sees as the future of science. At a border crossing while an Italian customs officer checks Andreas’ box of books for contraband, he openly and avidly reads the Discorsi when shouts from a gang of boys distracts him. They point to a little hut nearby saying there is a witch living there. Andrea lifts a boy up to the window and asks him what he sees. He replies, ‘an old girl cooking porridge at a stove’. But as Andrea clears customs and is about to leave he sees the boys pointing to a shadow cast on the house and yelling, ‘Marina’s a witch, she rides a broom at night!’ A new age indeed! Brecht ends Galileo on this disquieting irrational cry, reminding us of a time when women healers, midwives and just any old woman living alone were burnt as witches by Christian Europe, for not fitting into a patriarchal order, not that long ago.

Neither Hero nor Villain

In Brecht’s modern epic presentation of Galileo, he is neither a hero nor a villain. Heroes pitted against pitiless Destiny defined Greek Tragedy. Instead of heroes and villains or more recently goodies and baddies who we can cheer or boo, Brecht offers something quite rare and mighty strange. He offers scene after scene where the relations between the following dyadic terms are so finely calibrated that we really have to learn the irresistible joy of thinking for ourselves in the theatre.

Here are the dyadic terms:

senses and intellect,

gestures and speech,

subjects and objects,

costumes and movements

time and space,

body and mind,

feeling and thought

The terms on the left are rather more sensory and immediate, while those on the right tend to be more abstract, mediated. They are dyads not opposites, so the relays among them are intricate and complex, keeping us engaged. The mise-en-scène of the play is expansive, both terrestrial and cosmic. There is no longer an unmoving centre to the universe nor within the human brain, according to Galileo. Brecht’s Galileo presents both the cosmos and the human brain as dynamic systems. And Brecht’s modern epic theatrical idiom is the necessarily de-centred formal means adequate to demonstrating this new reality.

New Translations?

On October 31st 1992 (after 359 years) Pope John Paul II formally apologised for the ‘Galileo Case.’ It was the first of many apologies during his papacy. Is such a gesture by a ruler even thinkable in the Lankan context? I feel that Brecht’s Life of Galileo may resonate now with some Lankans engaged in the Aragalaya in the long term, as a process critically evaluating many spheres of Lankan life. I hope some folk reading this piece might think the time is ripe for a Sinhala and Tamil translation of Galileo some time soon.

Features

Remembering Ernest MacIntyre’s Contribution to Modern Lankan Theatre & Drama

Humour and the Creation of Community:

“As melancholy is sadness that has taken on lightness,

so humour is comedy that has lost its bodily weight”. Italo Calvino on ‘Lightness’ (Six Memos for the New Millennium (Harvard UP, 1988).

With the death of Ernest Thalayasingham MacIntyre or Mac, as he was affectionately known to us, an entire theatrical milieu and the folk who created and nourished Modern Lankan Theatre appear to have almost passed away. I have drawn from Shelagh Goonewardene’s excellent and moving book, This Total Art: Perceptions of Sri Lankan Theatre (Lantana Publishing; Victoria, Australia, 1994), to write this. Also, the rare B&W photographs in it capture the intensity of distant theatrical moments of a long-ago and far-away Ceylon’s multi-ethnic theatrical experiments. But I don’t know if there is a scholarly history, drawing on oral history, critical reviews, of this seminal era (50s and 60s) written by Lankan or other theatre scholars in any of our languages. It is worth remembering that Shelagh was a Burgher who edited her Lankan journalistic reviews and criticism to form part of this book, with new essays on the contribution of Mac to Lankan theatre, written while living here in Australia. It is a labour of love for the country of her birth.

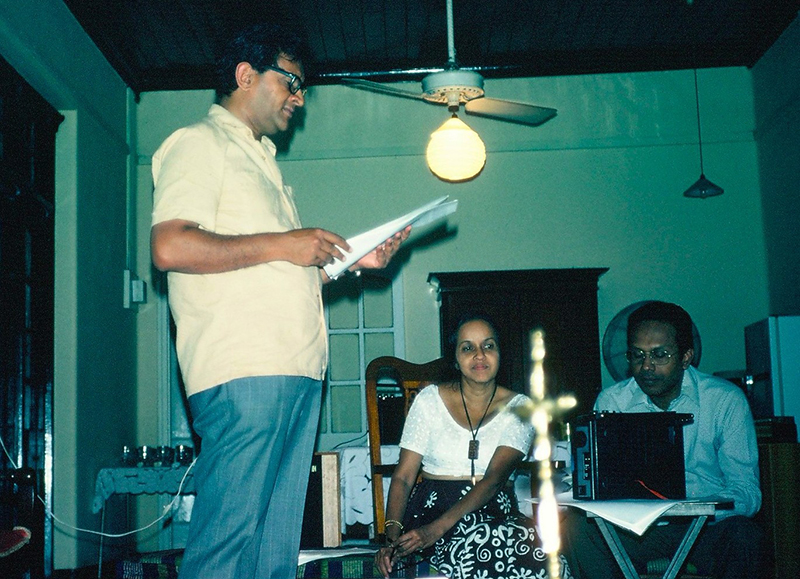

Here I wish to try and remember, now in my old age, what Mac, with his friends and colleagues from the University of Ceylon Drama Society did to create the theatre group called Stage & Set as an ‘infrastructure of the sensible’, so to speak, for theatrical activity in English, centred around the Lionel Wendt Theatre in Colombo 7 in the 60s. And remarkably, how this group connected with the robust Sinhala drama at the Lumbini Theatre in Colombo 5.

Shelagh shows us how Bertolt Brecht’s plays facilitated the opening up of a two-way street between the Sinhala and English language theatre during the mid-sixties, and in this story, Mac played a decisive role. I will take this story up below.

I was an undergraduate student in the mid-sixties who avidly followed theatre in Sinhala and English and the critical writings and radio programmes on it by eminent critics such as Regi Siriwardena and A. J. Gunawardana. I was also an inaugural student at the Aquinas University’s Theatre Workshop directed by Mac in late 1968, I think it was. So, he was my teacher for a brief period when he taught us aspects of staging (composition of space, including design of lighting) and theatre history, and styles of acting. Later in Australia, through my husband Brian Rutnam I became friends with Mac’s family including his young son Amrit and daughter Raina and followed the productions of his own plays here in Sydney, and lately his highly fecund last years when he wrote (while in a nursing home with his wife and comrade in theatre, Nalini Mather, the vice-principal of Ladies’ College) his memoir, A Bend in the River, on their University days. In my review in The Island titled ‘Light Sorrow -Peradeniya Imagination’ I attempted to show how Mac created something like an archaeology of the genesis of the pivotal plays Maname and Sinhabahu by Ediriweera Sarachchandra in 1956 at the University with his students. Mac pithily expressed the terms within which such a national cultural renaissance was enabled in Sinhala; it was made possible, he said, precisely because it was not ‘Sinhala Only’! The ‘it’ here refers to the deep theatrical research Sarachchandra undertook in his travels as well as in writing his book on Lankan folk drama, all of which was made possible because of his excellent knowledge of English.

The 1956 ‘Sinhala Only’ Act of parliament which abolished the status of Tamil as one of the National languages of Ceylon and also English as the language of governance, violated the fundamental rights of the Tamil people of Lanka and is judged as a violent act which has ricocheted across the bloodied history of Lanka ever since.

Mac was born in Colombo to a Tamil father and a Burgher mother and educated at St Patrick’s College in Jaffna after his father died young. While he wrote all his plays in English, he did speak Tamil and Sinhala with a similar level of fluency and took his Brecht productions to Jaffna. I remember seeing his production of Mother Courage and Her Children in 1969 at the Engineering Faculty Theatre at Peradeniya University with the West Indian actress Marjorie Lamont in the lead role.

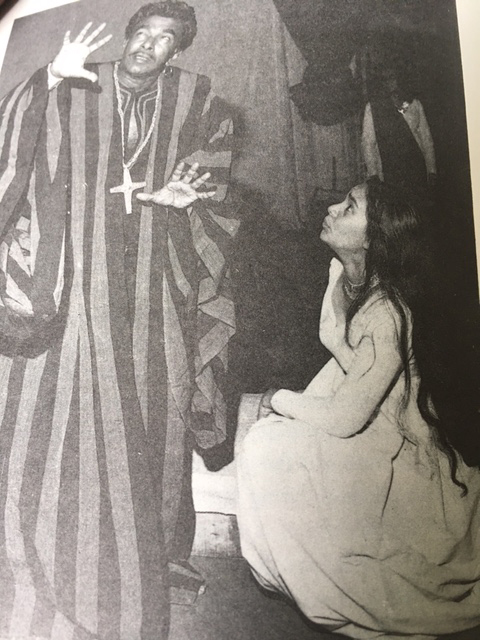

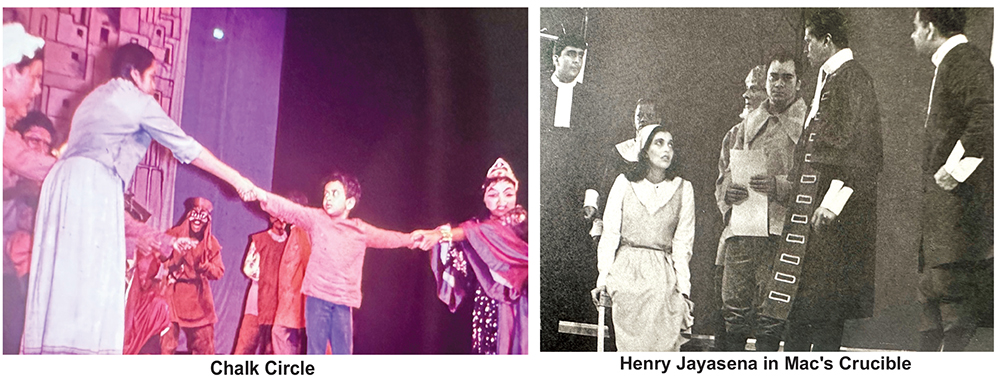

Stage & Set and Brecht in Lanka

The very first production of a Brecht play in Lanka was by Professor E.F. C. Ludowyk (Professor of English at Peradeniya University from 1933 to 1956) who developed the Drama Society that pre-existed his time at the University College by expanding the play-reading group into a group of actors. This fascinating history is available through the letter sent in 1970 to Shelagh by Professor Ludowyk late in his retirement in England. In this letter he says that he produced Brecht’s The Good Woman of Szechwan with the Dram Soc in 1949. Shelagh who was directed by Professor Ludowyk also informs us elsewhere that he had sent from England a copy of Brecht’s Caucasian Chalk Circle to Irangani (Meedeniya/Serasinghe) in 1966 and that she in turn had handed it over to Mac, who then produced it in a celebrated production with her in the role of Grusha, which is what opened up the two way-street between the English language theatre of the Wendt and the Lumbini Theatre in Sinhala. Henry Jayasena in turn translated the play into Sinhala, making it one of the most beloved Sinhala plays. Mac performed in Henry’s production as the naughty priest who has the memorable line which he was fond of reciting for us in Sinhala; ‘Dearly beloved wedding and funeral guests, how varied is the fate of man…’. The idiomatic verve of Henry’s translation was such that people now consider the Caucasian Chalk Circle a Sinhala play and is also a text for high school children, I hear. Even a venal president recently quoted a famous line of the selfless Grusha in parliament assuming urbanely that folk knew the reference.

Others will discuss in some detail the classical and modern repertoire of Western plays that Mac directed for Stage & Set and the 27 plays he wrote himself, some of which are published, so that here I just want to suggest the sense of excitement a Stage & Set production would create through the media. I recall how characters in Mac’s production of Othello wore costumes made of Barbara Sansoni’s handloom material crafted specially for it and also the two sets of lead players, Irangani and Winston Serasinghe and Shelagh and Chitrasena. While Serasinghe’s dramatic voice was beautifully textured, Chitrasena with his dancer’s elan brought a kinetic dynamism not seen in a dramatic role, draped in the vibrant cloaks made of the famous heavy handloom cotton, with daring vertical black stripes – there was electricity in the air. Karan Breckenridge as the Story Teller in the Chalk Circle and also as Hamlet, Alastair Rosemale-Cocq as Iago were especially remarkable actors within the ensemble casts of Stage & Set. When Irangani and Winston Serasinghe, (an older and more experienced generation of actors than the nucleus of Stage & Set), joined the group they brought a gravitas and a sense of deep tradition into the group as Irangani was a trained actor with a wonderful deep modulated voice rare on our stage. The photographs of the production are enchanting, luminous moments of Lankan theatre. I had a brief glimpse of the much loved Arts Centre Club (watering hole), where all these people galvanised by theatre, – architects, directors, photographers, artists, actors, musicians, journalists, academics, even the odd senator – all met and mingled and drank and talked regularly, played the piano on a whim, well into the night; a place where many ideas would have been hatched.

A Beckett-ian Couple: Mac & Nalini

In their last few years due to restricted physical mobility (not unlike personae in Samuel Beckett’s last plays), cared for very well at a nursing home, Mac and Nalini were comfortably settled in two large armchairs daily, with their life-long travelling-companion- books piled up around them on two shelves ready to help. With their computers at hand, with Nalini as research assistant with excellent Latin, their mobile, fertile minds roamed the world.

It is this mise-en-scene of their last years that made me see Mac metamorphose into something of a late Beckett dramatis persona, but with a cheeky humour and a voracious appetite for creating scenarios, dramatic ones, bringing unlikely historical figures into conversation with each other (Galileo and Aryabhatta for example). The conversations, rather more ludic and schizoid and yet tinged with reason, sweet reason. Mac’s scenarios were imbued with Absurdist humour and word play so dear to Lankan theatre of a certain era. Lankans loved Waiting for Godot and its Sinhala version, Godot Enakan. Mac loved to laugh till the end and made us laugh as well, and though he was touched by sorrow he made it light with humour.

And I feel that his Memoir was also a love letter to his beloved Nalini and a tribute to her orderly, powerful analytical mind honed through her Classics Honours Degree at Peradeniya University of the 50s. Mac’s mind however, his theatrical imagination, was wild, ‘unruly’ in the sense of not following the rules of the ‘Well-Made play’, and in his own plays he roamed where angels fear to tread. Now in 2026 with the Sinhala translation by Professor Chitra Jayathilaka of his 1990 play Rasanayagam’s Last Riot, audiences will have the chance to experience these remarkable qualities in Sinhala as well.

Impossible Conversations

In the nursing home, he was loved by the staff as he made them laugh and spoke to one of the charge nurses, a Lankan, in Sinhala. Seated there in his room he wrote a series of short well-crafted one-act plays bristling with ideas and strange encounters between figures from world history who were not contemporaries; (Bertolt Brecht and Pope John Paul II, and Galileo Galilei and a humble Lankan Catholic nun at the Vatican), and also of minor figures like poor Yorik, the court jester whom he resurrects to encounter the melancholic prince of Denmark, Hamlet.

Community of Laughter: The Kolam Maduwa of Sydney

A long life-time engaged in theatre as a vital necessity, rather than a professional job, has gifted Mac with a way of perceiving history, especially Lankan history, its blood-soaked post-Independence history and the history of theatre and life itself as a theatre of encounters; ‘all the world’s a stage…’. But all the players were never ‘mere players’ for him, and this was most evident in the way Mac galvanised the Lankan diasporic community of all ethnicities in Sydney into dramatic activity through his group aptly named the Kolam Maduwa, riffing on the multiple meanings of the word Kolam, both a lusty and bawdy dramatic folk form of Lanka and also a lively vernacular term of abuse with multiple shades of meaning, unruly behaviour, in Sinhala.

The intergenerational and international transmission of Brecht’s theatrical experiments and the nurturing of what Eugenio Barba enigmatically calls ‘the secret art of the performer’, given Mac’s own spin, is part of his legacy. Mac gave a chance for anyone who wanted to act, to act in his plays, especially in his Kolam Maduwa performances. He roped in his entire family including his two grand-children, Ayesha and Michael. What mattered to him was not how well someone acted but rather to give a person a chance to shine, even for an instance and the collective excitement, laughter and even anguish one might feel watching in a group, a play such as Antigone or Rasanayagam’s Last Riot.

A colleague of mine gave a course in Theatre Studies at The University of California at Berkeley on ‘A History of Bad Acting’ and I learnt that that was his most popular course! Go figure!

Mac never joined the legendary Dram Soc except in a silent walk-on role in Ludowyk’s final production before he left Ceylon for good. In this he is like Gananath Obeyesekere the Lankan Anthropologist who did foundational and brilliant work on folk rituals of Lanka as Dionysian acts of possession. While Gananath did do English with Ludowyk, he didn’t join the Dram Soc and instead went travelling the country recording folk songs and watching ritual dramas. Mac, I believe, did not study English Lit and instead studied Economics but at the end of A Bend in the River when he and his mates leave the hall of residence what he leaves behind is his Economics text book but instead, carries with him a copy of the Complete Works of Shakespeare.

I imagine that there was a ‘silent transmission of the secret’ as Mac stood silently on that stage in Shaw’s Androcles and the Lion; the compassionate lion. Mac understood why Ludowyk chose that play to be performed in 1956 as his final farewell to the country he loved dearly. Mac knew (among others), this gentle and excellent Lankan scholar’s book The Foot Print of the Buddha written in England in 1958.

Both Gananath and Mac have an innate sense of theatre and with Mac it’s all self-taught, intuitive. He was an auto-didact of immense mental energy. In his last years Mac has conjured up fantastic theatrical scenarios for his own delight, untrammelled by any spatio-temporal constraints. And so it happens that he gives Shakespeare, as he leaves London, one last look at his beloved Globe theatre burnt down to ashes, where ‘all that is solid melts into air’.

However, I wish to conclude on a lighter note touched by the intriguing epigram by Calvino which frames this piece. It is curious that as a director Mac was drawn to Shakespearean tragedy (Hamlet, Othello), rather than comedy. And it becomes even curiouser because as a playwright-director his own preferred genre was comedy and even grotesque-comedy and his only play in the tragic genre is perhaps Irangani. Though the word ‘Riot’ in Rasanayagam’s Last Riot refers to the series of Sinhala pogroms against Tamils, it does have a vernacular meaning, say in theatre, when one says favourably of a performance, ‘it was a riot!’, lively, and there are such scenes even in that play. So then let me end with Calvino quoting from Shakespeare’s deliciously profound comedy As You Like It, framed by his subtle observations.

‘Melancholy and humour, inextricably intermingled, characterize the accents of the Prince of Denmark, accents we have learned to recognise in nearly all Shakespeare’s plays on the lips of so many avatars of Hamlet. One of these, Jacques in As You Like It (IV.1.15-18), defines melancholy in these terms:

“But it is a melancholy of mine own, compounded of many simples, extracted from many objects, and indeed the sundry contemplation of my travels, in which my often rumination wraps me in a most humorous sadness.”’

Calvino’s commentary on Jacques’ self-perception is peerless:

‘It is therefore not a dense, opaque melancholy, but a veil of minute particles of humours and sensations, a fine dust of atoms, like everything else that goes to make up the ultimate substance of the multiplicity of things.’

Ernest Thalayasingham MacIntyre certainly was attuned to and fascinated to the end by the ‘fine dust of atoms, by the veil of minute particles of humours and sensations,’ but one must also add to this, laughter.

by Laleen Jayamanne ✍️

Features

Lake-Side Gems

With a quiet, watchful eye,

The winged natives of the sedate lake,

Have regained their lives of joyful rest,

Following a storm’s battering ram thrust,

Singing that life must go on, come what may,

And gently nudging that picking up the pieces,

Must be carried out with the undying zest,

Of the immortal master-builder architect.

By Lynn Ockersz ✍️

Features

IPKF whitewashed in BJP strategy

A day after the UN freshly repeated the allegation this week that sexual violence had been “part of a deliberate, widespread, and systemic pattern of violations” by the Sri Lankan military and “may amount to war crimes and crimes against humanity,” India praised its military (IPKF) for the operations conducted in Sri Lanka during the 1987-1990 period.

Soon after, as if in an echo, Human Rights Watch (HRW) in a statement, dated January 15, 2026, issued from Geneva, quoted Meenakshi Ganguly, Deputy Asia Director at the organisation, as having said: “While the appalling rape and murder of Tamil women by Sri Lankan soldiers at the war’s end has long been known, the UN report shows that systematic sexual abuse was ignored, concealed, and even justified by Sri Lankan government’s unwillingness to punish those responsible.”

Ganguly, who had been with the Western-funded HRW since 2004 went on to say: “Sri Lanka’s international partners need to step up their efforts to promote accountability for war crimes in Sri Lanka.”

To point its finger at Sri Lanka, or for that matter any other weak country, HRW is not that squeaky clean to begin with. In 2012, Human Rights Watch (HRW) accepted a $470,000 donation from Saudi billionaire Mohamed Bin Issa Al Jaber with a condition that the funds are not be used for its work on LGBT rights in the Middle East and North Africa. The donation was kept largely internal until it was revealed by an internal leak published in 2020 by The Intercept. Its Executive Director Kenneth Roth got exposed for taking the kickback. It refunded the money to Al Jaber only after the sordid act was exposed.

The UN, too, is no angel either, as it continues to play deaf, dumb and blind at an intrepid pace to the continuing unprecedented genocide against Palestinians and other atrocities being committed in West Asia and other parts of the world by Western powers.

The HRW statement was headlined ‘Sri Lanka: ‘UN Finds Systemic Sexual Violence During Civil War’, with a strap line ‘Impunity Prevails for Abuses Against Women, Men; Survivors Suffer for Years’

HRW reponds

The HRW didn’t make any reference to the atrocities perpetrated during the Indian Army deployment here.

The Island sought Ganguly’s response to the following queries:

* Would you please provide the number of allegations relating to the period from July 1987 to March 1990 when the Indian Army had been responsible for the Northern and Eastern Provinces of Sri Lanka and the Sri Lanka military confined to their camps, in terms of the Indo-Lanka accord.

* Have you urged the government of India to take tangible measures against the Indian Army personnel for violations perpetrated in Sri Lanka?

* Would you be able to provide the number of complaints received from foreign citizens of Sri Lankan origin?

Meenakshi responded: Thanks so much for reaching out. Hope you have been well? We can’t speak about UN methodology. Please could you reach out to OHCHR. I am happy to respond regarding HRW policies, of course. We hope that Sri Lankan authorities will take the UN findings on conflict-related sexual violence very seriously, regardless of perpetrator, provide appropriate support to survivors, and ensure accountability.

Mantri on IPKF

The Indian statement, issued on January 14, 2026, on the role played by its Army in Sri Lanka, is of significant importance at a time a section of the international community is stepping up pressure on the war-winning country on the ‘human rights’ front.

Addressing about 2,500 veterans at Manekshaw Centre, New Delhi, Indian Defence Minister Raksha Mantri referred to the Indian Army deployment here whereas no specific reference was made to any other conflicts/wars where the Indian military fought. India lost about 1,300 officers and men here. At the peak of Indian deployment here, the mission comprised as many as 100,000 military personnel.

According to the national portal of India, Raksha Mantri remembered the brave ex-servicemen who were part of Operation Pawan launched in Sri Lanka for peacekeeping purposes as part of the Indian Peacekeeping Force (IPKF) almost 40 years ago. Mantri’s statement verbatim: “During the operation, the Indian forces displayed extraordinary courage. Many soldiers laid down their lives. Their valour, sacrifices and struggles did not receive the respect they deserved. Today, under the leadership of PM Modi, our government is not only openly acknowledging the contributions of the peacekeeping soldiers who participated in Operation Pawan, but is also in the process of recognising their contributions at every level. When PM Modi visited Sri Lanka in 2015, he paid his respects to the Indian soldiers at the IPKF Memorial. Now, we are also recognising the contributions of the IPKF soldiers at the National War Memorial in New Delhi and giving them the respect they deserv.e” (https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetailm.aspx?PRID=2214529®=3&lang=2)

One-time President of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), and ex-Home Minister Mantri received the Defence Portfolio in 2019. There hadn’t been a similar statement from any Modi appointed Defence Minister since he became the Prime Minister in 2014.

Perhaps, we should remind Mantri that Operation Pawan hadn’t been launched for peacekeeping purposes and the Indian Army deployment here cannot be discussed without examining the treacherous Indian destabilisation project launched in the early ’80s.

Nothing can be further from the truth than the attempt to describe Operation Pawan as a peacekeeping mission. India destabilised and terrorised Sri Lanka to its heart’s content that the then President JRJ had no option but to accept the so-called Indo-Lanka accord and the deployment of the Indian Army here to supervise the disarming of terrorist groups sponsored by India. Once the planned disarming of terrorist groups went awry in August, 1987 and the LTTE engineered a mass suicide of a group of terrorists who had been held at Palaly airbase, thereby Indian peacekeeping mission was transformed to a military campaign.

Mantri, in his statement, referred to the Indian Army memorial at Battaramulla put up by Sri Lanka years ago. The Indian Defence Minister seems to be unaware of the first monument installed here at Palaly in memory of 33 Indian commandos of the 10 Indian Para Commando unit, including Lieutenant Colonel Arun Kumar Chhabra who died in a miscalculated raid on the Jaffna University at the commencement of Operation Pawan.

BJP politics

Against the backdrop of Mantri’s declaration that India recognised the IPKF at the National War Memorial in New Delhi, it would be pertinent to ask when that decision was taken. The BJP must have decided to accommodate the IPKF at the National War Memorial in New Delhi recently. Otherwise Mantri’s announcement would have been made earlier. Obviously, Modi, the longest serving non-Congress Prime Minister of India, didn’t feel the need to take up the issue vigorously during his first two terms. Modi won three consecutive terms in 2014, 2019 and 2024. Congress great Jawaharlal Nehru is the only other to win three consecutive parliamentary elections in 1951, 1957 and 1962.

The issue at hand is why India failed to recognise the IPKF at the National War Memorial for so long. The first National War Memorial had been built and inaugurated in January 1972 following the Indo-Pakistan war of 1971, but under Modi’s direction India set up a new memorial, spread over 40 acres of land near India Gate Circle. Modi completed the National War Memorial project during his first term.

No one would find fault with India for honouring those who paid the supreme sacrifice in Sri Lanka, but the fact that the deployment of the IPKF took place here under the overall destabilisation project cannot be forgotten. India cannot, under any circumstances, absolve itself of the responsibility for the death and destruction caused as a result of the decision taken by Indira Gandhi, in her capacity as the Prime Minister, to intervene in Sri Lanka. Her son Rajiv Gandhi, in his capacity as the Prime Minister, dispatched the IPKF here after Indian,trained terrorists terrorised the country. India exercised terrorism as an integral part of their overall strategy to compel Sri Lanka to accept the deployment of Indian forces here under the threat of forcible occupation of the Northern and Eastern provinces.

India could have avoided the ill-fated IPKF mission if Premier Rajiv Gandhi allowed the Sri Lankan military to finish off the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in 1987. Unfortunately, India carried out a forced air-drop over the Jaffna peninsula in June, 1987 to compel Sri Lanka to halt ‘Operation Liberation,’ at that time the largest ever ground offensive undertaken against the LTTE. Under Indian threat, Sri Lanka amended its Constitution by enacting the 13th Amendment that temporarily merged the Eastern Province with the Northern Province. That had been the long-standing demand of those who propagated separatist sentiments, both in and outside Parliament here. Don’t forget that the merger of the two provinces had been a longstanding demand and that the Indian Army was here to install an administration loyal to India in the amalgamated administrative unit.

The Indian intervention here gave the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) with an approving wink from Washington as India was then firmly in the Soviet orbit, an opportunity for an all-out insurgency burning anything and everything Indian in the South, including ‘Bombay onions’ as a challenge to the installation of the Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation front (EPRLF)-led administration in the North-East province in November 1988. How the Indian Army installed ex-terrorist Varatharaja Perumal’s administration and the formation of the so-called Tamil National Army (TNA) during the period leading to its withdrawal made the Indian military part of the despicable Sri Lanka destabilisation project.

The composition of the first NE provincial council underscored the nature of the despicable Indian operation here. The EPRLF secured 41 seats, the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress (SLMC) 17 seats, Eelam National Democratic Liberation Front (ENDLF) 12 and the United National Party (UNP) 1 in the 71-member council.

The Indian intelligence ran the show here. The ENDLF had been an appendage of the Indian intelligence and served their interests. The ENDLF that had been formed in Chennai (then Madras) by bringing in those who deserted EPRLF, PLOTE (People’s Liberation Organisation of Tamil Eelam) and Three Stars, a PLOTE splinter group led by Paranthan Rajan was accused of committing atrocities. Even Douglas Devananda, whose recent arrest over his failure to explain the disappearance of a weapon provided to him by the Sri Lanka Army, captured media attention, too, served the ENDLF for a short period. The ENDLF also contested the parliamentary polls conducted under Indian Army supervision in February 1989.

The ENDLF, too, pulled out of Sri Lanka along with the IPKF in 1990, knowing their fate at the hands of the Tigers, then honeymooning with Premadasa.

Dixit on Indira move

The late J.N. Dixit who was accused of behaving like a Viceroy when he served as India’s High Commissioner here (1985 to 1989) in his memoirs ‘Makers of India’s Foreign Policy: Raja Ram Mohun Roy to Yashwant Sinha’ was honest enough to explain the launch of Sri Lanka terrorism here.

In the chapter that also dealt with Sri Lanka, Dixit disclosed the hitherto not discussed truth. According to Dixit, the decision to militarily intervene had been taken by the late Indira Gandhi who spearheaded Indian foreign policy for a period of 15 years – from 1966 to 1977 and again from 1980 to 1984 (Indira was assassinated by her Sikh bodyguards in that year). That disastrous decision that caused so much death and destruction here and the assassination of her son Rajiv Gandhi had been taken during her second tenure (1980 to 1984) as the Prime Minister.

The BJB now seeking to exploit Indira Gandhi’s ill-fated decision probably taken at the onset of her second tenure as the Premier, came into being in 1980. Having described Gandhi’s decision to intervene in Sri Lanka as the most important development in India’s regional equations, one-time Foreign Secretary (December 1991 to January 1994) and National Security Advisor (May 2004 to January 2005) declared that Indian action was unavoidable.

Dixit didn’t mince his words when he mentioned the two major reasons for Indian intervention here namely (1) Sri Lanka’s oppressive and discriminating policies against Tamils and (2) developing security relationship with the US, Pakistan and Israel. Dixit, of course, didn’t acknowledge that there was absolutely no need for Sri Lanka to transform its largely ceremonial military to a lethal fighting force if not for the Indian destabilisation project. The LTTE wouldn’t have been able to enhance its fighting capabilities to wipe out a routine army patrol at Thinnaveli, Jaffna in July 1983, killing 13 men, including an officer, without Indian training. That was the beginning of the war that lasted for three decades.

Anti-India project

Dixit also made reference to the alleged Chinese role in the overall China-Pakistan project meant to fuel suspicions about India in Nepal and Bangladesh and the utilisation of the developing situation in Sri Lanka by the US and Pakistan to create, what Dixit called, a politico-strategic pressure point in Sri Lanka.

Unfortunately, Dixit didn’t bother to take into consideration Sri Lanka never sought to expand its armed forces or acquire new armaments until India gave Tamil terrorists the wherewithal to challenge and overwhelm the police and the armed forces. India remained as the home base of all terrorist groups, while those wounded in Sri Lanka were provided treatment in Tamil Nadu hospitals.

At the concluding section of the chapter, titled ‘AN INDOCENTRIC PRACTITIONER OF REALPOLITIK,’ Dixit found fault with Indira Gandhi for the Sri Lanka destabilisation project. Let me repeat what Dixit stated therein. The two foreign policy decisions on which she could be faulted are: her ambiguous response to the Russian intrusion into Afghanistan and her giving active support to Sri Lanka Tamil militants. Whatever the criticisms about these decisions, it cannot be denied that she took them on the basis of her assessments about India’s national interests. Her logic was that she could not openly alienate the former Soviet Union when India was so dependent on that country for defense supplies and technologies. Similarly, she could not afford the emergence of Tamil separatism in India by refusing to support the aspirations of Sri Lankan Tamils. These aspirations were legitimate in the context of nearly fifty years of Sinhalese discrimination against Sri Lankan Tamils.

The writer may have missed Dixit’s invaluable assessment if not for the Indian External Affairs Ministry presenting copies of ‘Makers of India’s Foreign Policy: Raja Ram Mohun Roy to Yashwant Sinha’ to a group of journalists visiting New Delhi in 2006. New Delhi arranged that visit at the onset of Eelam War IV in mid-2006. Probably, Delhi never considered the possibility of the Sri Lankan military bringing the war to an end within two years and 10 months. Regardless of being considered invincible, the LTTE, lost its bases in the Eastern province during the 2006-2007 period and its northern bases during the 2007-2009 period. Those who still cannot stomach Sri Lanka’s triumph over separatist Tamil terrorism, propagate unsubstantiated allegations pertaining to the State backing excesses against the Tamil community.

There had been numerous excesses and violations on the part of the police and the military. There is no point in denying such excesses happened during the police and military action against the JVP terrorists and separatist Tamil terrorists. However, sexual violence hadn’t been State policy at any point of the military campaigns or post-war period. The latest UN report titled ‘ACCOUNTABILITY FOR CONFLICT RELATED VIOLENCE IN SRI LANKA’ is the latest in a long series of post-war publications that targeted the war-winning military. Unfortunately, the treacherous Sirisena-Wickremesinghe Yahapalana government endorsed the Geneva accountability resolution against Sri Lanka in October 2015. Their despicable action caused irreversible damage and the ongoing anti-Sri Lanka project should be examined taking into consideration the post-war Geneva resolution.

By Shamindra Ferdinando ✍️

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoExtended mind thesis:A Buddhist perspective

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoAmerican rulers’ hatred for Venezuela and its leaders

-

Business19 hours ago

Business19 hours agoComBank advances ForwardTogether agenda with event on sustainable business transformation

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoRemembering Cedric, who helped neutralise LTTE terrorism

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoCORALL Conservation Trust Fund – a historic first for SL

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoA puppet show?

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoHistory of St. Sebastian’s National Shrine Kandana

-

Opinion19 hours ago

Opinion19 hours agoConference “Microfinance and Credit Regulatory Authority Bill: Neither Here, Nor There”