Features

All things are impermanent

Sunday short story

(Excerpted from Saris and Grapefruit, a collection of short stories by Rukmini Attygalle)

Rupa Jayasena gazed intently on the vista below, as she sat in the front veranda of her home, high up on the hill of Hanthana, overlooking the Peradeniya University’s green campus scattered with trees and bushes in bloom. She could discern within the meticulously landscaped terrain the Peradeniya-Galaha road winding its way to Getambe and beyond. She would sit in the veranda all afternoon with frequent cups of tea and watch the young men and women walking between their residential halls and lecture rooms, clutching books and files. They were in happy groups; or couples absorbed with each other; or hurrying single students.

But now her fading eyes could not pick out details; she only discerned blurred green, dotted with coloured smudges. Her memory, however, carried a scene of beauty and that imbued the indistinct view, so it brought joy to her. Even the domba tree in her own garden had lost definition. She could only make out the general shape of the majestic tree, the dark green of the leaves but not their sheen.

As she sat in her wheelchair, enjoying the bird song and fresh evening breeze that wafted across her face, she tried to accept the fact that she was gradually losing her sight.

She was 88-years old and subject to the frailties of advanced years. Her arthritic joint pains, her swollen feet, her diminishing ability to balance, bound her to the wheelchair and reliance on carers. What bothered her most, however, was a lurking dread that she was, perhaps, losing her memory too. Sometimes her mind was sharp and her thoughts clear; at other times she felt a vague sense of unease not knowing exactly where she was and who she was speaking with.

Her consciousness seemed to be slipping in and out of her mind. She was aware of this and clung to it because awareness, she was told, was a prevention to memory, loss. Sometimes she could not discern the time lapse between events. Often certain past events came up in her mind, but when they had occurred, or how, were lost. Memories flashed through, her mind as independent entities, with no connection to the rest of her life. She was losing control and she hated it. She knew she, was going downhill for sure, but the hill was not steep enough to gather speed. The descent was grindingly and painfully slow.

“Nona, better come in now. We must close the doors and windows before the mosquitoes enter,” said Soma. Soma had been in Rupa’s employment for 40 years and was now part of the family. She and Menika were Rupa’s carers; well-paid and seen to by her son, Ajith.

As Rupa was wheeled indoors, she noticed someone standing by the dining table with a cup in hand. Rupa turned her head back to ask Soma who it was.

“It’s Menika, Nona, the other person who looks after you. She has made you a nice cup of soup.”

“When did she come?”

“She has been here for some time, Nona. She is very fond you.” The two women exchanged looks of sympathetic understanding.

“Ah! Yes, of course,” Rupa sighed, “switch on the lights, will you. I couldn’t recognize her in the dark.”

Rupa’s eyes rested on a basket of orchids on the sideboard. “From where are these orchids? They look beautiful.”

“Why, Nona, they were sent last week by Ranjini Madam for your birthday,” Soma explained patiently.

“Who is this Ranjini Madam?”

“Your daughter, Nona, your daughter who lives in England.” “Ah! Yes. My daughter lives in England.” She paused for a few seconds and continued, “Her son is ill, Kelle, very ill, I am so sad. I can’t help her at all.”

Although her mind meandered without course or direction, the thought of her grandson’s illness stuck like a barnacle in some recess of her mind, not to be easily prised out. This particular memory, often came linked to her memory of her daughter’s illness with meningitis during her childhood. The agony she had suffered at the time was indelibly stamped in her mind. These memories kept resurfacing periodically; while they emerged and submerged, they were never completely lost. They hovered in the background of a fog of temporary forgetfulness.

Rupa took a sip from the bowl the woman Menika offered her. She liked her karapincha soup, she relished its pungent flavour.

“How can you help Ranjini Madam, Nona,” Soma continued the conversation. “You are not well yourself. Anyway, Ranjan Baba will get the best medical care over there. Don’t worry, Nona.”

Rupa’s memories slowly tapered down to nothingness. She is back in the present moment. She looks at her swollen feet and tries to wiggle her toes.

“Water retention, water retention,” she mutters to herself. She hears the sound of a gecko bad omen, bad omen. Suddenly, the purple orchids on the side-board jogs a memory.

“Kelle, what happened to the pot of African violets? It used to be in the veranda. I haven’t seen them for some time.”

“What African violets, Nona? We haven’t had African violets for a long time.”

“Why not?” Rupa sounded annoyed. “The African violet pot Loku Mahattaya brought me for my birthday? They were always in bloom, remember? We used to keep them in the veranda so they would get the morning sun.”

Soma did not want to remind Rupa that her husband was dead 15 years. She loved her Nona and always avoided causing her distress. So, she changed the direction of their conversation.

“Podi Mahattaya called this afternoon to find out how you are getting on. He wanted me to call his friend, Vijita Mahattaya and ask him to get your blood pressure checked. He did not want me to disturb your afternoon nap. He also asked me to tell you that Nishard Baba has got a place in Oxford University. Anyway, he is going to call you tomorrow morning.”

“Where is Ajith? Where is Podi Mahattaya? Is he in Oxford? He did not tell me that he was going to England! Good if he is there, he can be of help to Ranjini Madam. She must be so worried and

unhappy…” The sad memory was about to resurface when Soma interrupted.

“No, Nona, Podi Mahattaya is working in Dubai. He has to work very hard now to educate the two boys and to take care of us. He is so good, Nona, he makes sure that we have everything we need. He is always phoning to find out how we are.”

“Yes, Kella.” Rupa sighed deeply. Tears welled in her eyes. “He has always been a caring and loving child. He … he …” and her voice trailed off. Her tears dried. Something was gnawing at her; something sad but not identifiable. Rupa was back in her depressive apathy.

Ajith Jayasena, structural engineer, worked in Dubai. When he realized that both his sons showed academic ability from their young age, he was determined to give them the best education money could buy. Although he enjoyed his work in Sri Lanka and life in his place of birth, he soon realized that there was no way he could give the boys a foreign education unless he got a much better-paid job overseas.

Dubai was developing and expanding rapidly. High-rise buildings, luxury hotels, new roads and motorways, were coming up at an amazing speed. Dubai was calling out for engineering skills worldwide, and Ajith procured a job well paid and with prospects.

“I am so happy, Putha,” Rupa had exclaimed when she heard of his new employment. “This is a great opportunity for you and your family. Send the two little professors to a good international school over there. They will prepare the boys for higher education.”

Ajith remembered how proud his mother was of the two boys she named ‘My little professors.’ She had been a teacher, at first in Girls’ High School, Kandy, and later privately tutored undergraduates in English; improvement in English skills being a priority of the rural students. As a schoolboy, Ajith’s homework was supervised by her. He would often exclaim in exasperation,,, “Amma, you are such a hard taskmaster. Even the teachers at college are not as wicked as you!”

“Of course, with a lazy and crafty son like you, I have no choice.” Rupa would shout out and sometimes her voice rose. But the invisible vibrations of love that accompanied the scream pulverized and dispersed any anger or resentment that involuntarily rose in the son.

He loved his mother so much that it pained him to see her succumb to old age. He knew it was inevitable, but that did not reduce his pain of mind. He wished he could be with her constantly, because he knew that his presence always cheered and comforted her. They would tease each other incessantly but there was no question about the depth of the maternal-filial love they shared. Despite her age, the mother-child bond was still very strong.

Ajith felt she needed him the most now and needed him close at hand, sharing her pain, her frustration, empathizing with her feeling of incapability, showing her how much he loved her. It would make a difference to his mother, and to him too. But he had his duty by his family: his sons’ welfare had to supersede his mother’s need of him. Of course, there were the flying visits; but these were inadequate. He had to carry on working at his lucrative job to support his sons, his wife and his mother. A deep anxiety was building up within him; especially as he remembered his last visit home.

“Hello Amma!” He had exclaimed, walking toward her with open arms. She had been sitting in her wheelchair in the living I room with a magazine on her lap. She looked up at him blankly. Maybe she had gone blind, he surmised, with alarm. He knew her sight was failing. But when she failed to recognize his voice, he knew it was something graver than her hearing.

“Amma,” he cried, choking with emotion. “I am here to see you.” He bent down, kissed her and took her hand in his. There was no response. His fists clenched and he experienced a lightening in his chest.

Had they lost her? Had she left them and ensconced herself in a world beyond their reach?

“Are you the doctor?” Rupa hesitatingly asked. “You know, doctor, my joints are becoming extremely painful. Can you give me some pain killer?”

Ajith brushed away the tears gathered in his eyes with the back of his hand. Just then Soma entered, wiping her hands in a dish cloth.

“Podi Mahattaya!” she exclaimed joyfully. “What a surprise. When did you come? You never told us you were coming. You’ll stay for lunch, right? I will make your favourite ambulthial. Menika just returned with some fresh thora maalu.”

It was after this welcoming burst that Soma noticed Rupa’s blank expression and Alith’s despondency.

“Nona, Ajith Mahattaya your son is here to see you. He has come all the way from Dubai. Isn’t it wonderful? He is looking good, no?”

He noticed a flicker in Rupa’s tired eyes. She now focused them fully on Ajith’s face a furrow deepening between her eyebrows. Crows’ feet at the outer corners of her eyes wrinkled as she peered deep into his eyes. Recognition was beginning to dawn.

“Ah! Yes, of course!” Her face lit up with joy. “Ajith Putha, it’s lovely to see you! Did you forget to shave this morning?” Ajith sighed with relief. She was back with them. She was back to her normal self, or almost. But the question was for how long?

Ajith pushed aside the papers on his desk and reached for the phone. After just two rings Ranjini answered her mobile phone. “Nangi, how is Ranjan?”

“Not so good.” She did not want to disturb the other patients in the ward, nor did she want her son to hear the conversation. So, she moved out to the corridor.

“He is not responding to the chemotherapy.” Ranjini’s voice was breaking not because of a bad telephone connection, but because she couldn’t get the words out. Between suppressed sobs, Ranjini explained the full extent of her son’s illness.

“He is really suffering, Aiya. He even asked me if he can’t be given an injection to die! I simply don’t know what to do.” The knot in Ajith’s gut tightened. “What about the experimental drugs they told you about?”

“Yes, Aiya, but they also warned me of the risks. There is a chance of an adverse reaction. Ranjan may not pull through. The suffering may be severe. I don’t know what decision to make. Should I say ‘yes’ or ‘no’. I wish Amma was here.”

“What choice do you have, Nangi’? The new drug may work. I think you should go for it. We just have to hope and pray. What about Upali – what does he say?”

“Oh! Upali!” Ranjini heaved a sigh. “He breezes in and out of the hospital to mark the register! He is fully absorbed now with his new family. He says the decision should be mine as I have custody over Ranjan.” She paused. “Do you really think I should go for the new drug?”

“Yes Nangi, I do. That is Ranjan’s only chance, isn’t it?”

“OK then…” Her voice trailed, ending almost inaudibly. Then died, picked up and queried,

“How is Amma? How was she when you last saw her? I feel so bad that I haven’t been to see her for so long. But, you know, AIya…

“Of course, you can’t leave your son. He needs you and Amma fulIy understands. She was OK when I last saw her. Her arthritis is playing up a bit but …”

“Did she recognize you? Soma said that at times she does not know whom she is talking to.”

“No, no, she was OK. She even joked with me about not having shaved.” Ajith tried to laugh it off. Ranjini did not detectt its falsity and seemed relieved. But deep down, she knew her mother was on the decline. She wanted so much to see her and give her some comfort. But what could she do?

After the call, Ranjini returned to her son’s bedside. The doctors were due any moment. The curtains that made a cubicle around her son’s bed were drawn providing privacy. She felt hemmed in, trapped, suffocated by the central heating. The smell of disinfectant and the clinical ambience oppressed her. She longed to go out of doors, out of the hospital to breathe fresh air, fill her lungs with it, feel the cool breeze on her face, brush off the falling leaves from her shoulders and smell the autumn air.

She had made up her mind to inform the doctors she agreed to the experimental drug being administered to her son. She suddenly felt herself jolt. Was she signing Ranjan’s death warrant? Surely, surely not! As her brother had said, this was the only chance to save her son, fraught with risk though it was. This decision had to be made. A black ponderous heaviness seemed to descend on her. Its gloom engulfed her. Her entire body trembled. But an inner strength pushed her mind and body to regain normalcy. It seemed as if some outside force entered her body to make her strong so she could face the ordeal looming close ahead of her.

When she told the doctors, she was willing to take the risk of the new drug, they welcomed her decision. “Yes, Mrs Soysa, that is the only chance your son has. We will do our very best for him. We know what a heavy burden it has been for you to decide, but you have done right.”

Ranjini signed the consent form with trembling hand and racing heart. Her sharply focused, fearful mind and doubting thoughts slowly dissipated once the form was taken away. Mixed with the harrowing worry over her son, was an image of her mother that kept intruding. It was as if a raw nerve tingled. She sat back and assessed her situation. It was dire. Her son was dying in one part of the world and in another was her gradually but surely declining mother. She was boxed in the middle, loving both, caring for both and fearful for both.

She realized this was karma vipaka. A past negative karma had caught up with her and made her a victim. She also realized that this could also change; a good karma of the past might surface and mercifully lighten her present stress and douse the danger. She had to accept it all with equanimity, she decided with resignation.

Ranjini continued to sit beside her son’s bed, with these and other thoughts swirling in her mind. The ward matron tiptoed to her. “We will be moving the patient to a single room Room 1032 on the same floor. He will settle down and feel better when you visit in the evening.”

She was exhausted; she needed to go home, shower and rest before returning. She kissed her sleeping son, whispered a blessing and tiptoed out of the ward.

Ajith was anxious to know how Ranjan was responding to the first dose of the test drug.

“It’s too early to tell,” Ranjini replied with hope in her voice. They say his condition is stable and there has been a slight positive reaction. But three more doses and then more scans and blood tests will give us an indication of how matters are progressing. I just live in hope, Aiya.”

“Don’t you worry, Nangi, things will work out. My friend, Vijita has arranged for a senior monk of the Dalada Maligawa to conduct pirith chanting daily until Ranjan takes a turn for the better. That will surely help. He is also doing a bodhi pooja. You just spread metta while being with Ranjan, and even at home. Pirith vibrations do have a powerful and positive effect. So, cheer up, girl! If you can,” he added.

A few days later, Vijita called Ajith from Peradeniya. “Machang, your Amma has gone down with a chest infection and I have entered her to the Kandy Hospital. She seems to be getting weaker by the day. Maybe you should come over.”

Ajith took the earliest available flight to Sri Lanka. He decided not to inform Ranjini until he assessed their mother’s condition. Going home to drop his suitcase, he found Soma distraught.

“Mahattaya, our Nona is very ill. She does not recognize anyone, even me. However bad her memory had become she always knew who I was. You see, I have always been with her, never left her alone.” This deterioration of her mistress affected Soma badly. It stung like a hundred debaras and nibbled into her like a hundred kadiyas.

Rupa was conscious of a struggle going on within her, as though her life force was trying to liberate itself from the restraining clutches of her physical body. She drifted momentarily out of consciousness but was soon aware of her body and mind. She felt her body jerk once, twice, thrice and then relax. She lay very still as though dead but not quite dead. Her breathing turned shallow, not laboured. Minute by minute, drip by drip, her life was ebbing away. She was no longer in pain. Not wanting to struggle to live, she just let her life slip away. She clung to nothing. She gradually became aware of a deep, deep peace envelope her being.

She opened her eyes and saw Ajith standing by her bedside. She looked direct into his eyes. In that instant Ajith knew his mother had regained her memory and was fully conscious of what was going on. Her eyes were windows to her inner being. He saw in them a calm acceptance and a deep serenity. She gave him a beautiful smile. He held her hand firmly, hoping his energy would flow into her.

“Putha,” she whispered, barely audible. He bent down and placed his ear near her lips. “I am fine, Putha just let me go.” Ajith kissed his mother’s forehead and continued holding her hand, more gently now. He lightly stroked her arm with his other hand and chanted a stanza of pirith. While there was an underlying sadness, there was also much comfort in the acceptance of her end and the knowledge that his mother was now at peace no longer trapped in a painful decaying body.

He rang for the resident doctor who came immediately and confirmed that the patient had died.

Ajith went out of the room after a last farewell and phoned his sister.

“Nangi, Amma just passed away. It was very peaceful. She looks so serene. She told me just before she breathed her last, that she was fine and relieved of all pain.”

“Yes, Aiya, I know.”

“How?”

“She came to say goodbye.”

“What?”

“Yes,” Ranjini continued, after a short pause. He heard her deep breathing, but no sob.

“I was sitting by Ranjan’s bed. I was tired, so I lay my head on the edge of the bed. Maybe I dozed off; maybe I dreamed Perhaps my thoughts had gone to Amma in a dream-like state I was however conscious of me in hospital beside my son who was fast asleep. I heard the words Baby Girl and it was Amma’s voice soft and clear. I distinctly heard this. I had forgotten that she used that name for me. That remembrance woke me, I sat up. And then I saw her standing by the door luminous, ethereal, beautiful. She had a lovely smile and her eyes were really bright I had never seen her so radiant.”

“‘Ranji-Boy is going to be all right,’ she said, and I heard het clearly. Her message penetrated my brain and I suddenly felt such optimism, and gratitude too. I told her I was sorry I could not visit her. She said, `I understand,’ with such love in her voice. `I understand. I was a mother too.’ Then she disappeared.”

There was silence from the other end of the telephone connection. “Aiya, are you there?”

“Yes.”

“You know something?”

“What?”

“I feel as if a huge dark cloud has lifted off me. I feel a great sense of relief, and funnily enough, gladness too.”

“So do I,” added Ajith.

Features

Australia’s social media ban: A sledgehammer approach to a scalpel problem

When governments panic, they legislate. When they legislate in panic, they create monsters. Australia’s world-first ban on social media for under-16s, which came into force on 10 December, 2025, is precisely such a monster, a clumsy, authoritarian response to a legitimate problem that threatens to do more harm than good.

When governments panic, they legislate. When they legislate in panic, they create monsters. Australia’s world-first ban on social media for under-16s, which came into force on 10 December, 2025, is precisely such a monster, a clumsy, authoritarian response to a legitimate problem that threatens to do more harm than good.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese hailed it as a “proud day” for Australian families. One wonders what there is to be proud about when a liberal democracy resorts to blanket censorship, violates children’s fundamental rights, and outsources enforcement to the very tech giants it claims to be taming. This is not protection; it is political theatre masquerading as policy.

The Seduction of Simplicity

The ban’s appeal is obvious. Social media platforms have become toxic playgrounds where children are subjected to cyberbullying, addictive algorithms, and content that can genuinely harm their mental health. The statistics are damning: 40% of Australian teens have experienced cyberbullying, youth self-harm hospital admissions rose 47% between 2012 and 2022, and depression rates have skyrocketed in tandem with smartphone adoption. These are real problems demanding real solutions.

But here’s where Australia has gone catastrophically wrong: it has conflated correlation with causation and chosen punishment over education, restriction over reform, and authoritarian control over empowerment. The ban assumes that removing children from social media will magically solve mental health crises, as if these platforms emerged in a vacuum rather than as symptoms of deeper societal failures, inadequate mental health services, overworked parents, underfunded schools, and a culture that has outsourced child-rearing to screens.

Dr. Naomi Lott of the University of Reading hit the nail on the head when she argued that the ban unfairly burdens youth for tech firms’ failures in content moderation and algorithm design. Why should children pay the price for corporate malfeasance? This is akin to banning teenagers from roads because car manufacturers built unsafe vehicles, rather than holding those manufacturers accountable.

The Enforcement Farce

The practical implementation of this ban reads like dystopian satire. Platforms must take “reasonable steps” to prevent access, a phrase so vague it could mean anything or nothing. The age verification methods being deployed include AI-driven facial recognition, behavioural analysis, government ID scans, and something called “AgeKeys.” Each comes with its own Pandora’s box of problems.

Facial recognition technology has well-documented biases against ethnic minorities. Behavioural analysis can be easily gamed by tech-savvy teenagers. ID scans create massive privacy risks in a country that has suffered repeated data breaches. And zero-knowledge proof, while theoretically elegant, require a level of technical sophistication that makes them impractical for mass adoption.

Already, teenagers are bragging online about circumventing the restrictions, prompting Albanese’s impotent rebuke. What did he expect? That Australian youth would simply accept digital exile? The history of prohibition, from alcohol to file-sharing, teaches us that determined users will always find workarounds. The ban doesn’t eliminate risk; it merely drives it underground where it becomes harder to monitor and address.

Even more absurdly, platforms like YouTube have expressed doubts about enforcement, and Opposition Leader Sussan Ley has declared she has “no confidence” in the ban’s efficacy. When your own political opposition and the companies tasked with implementing your policy both say it won’t work, perhaps that’s a sign you should reconsider.

The Rights We’re Trading Away

The legal challenges now percolating through Australia’s High Court get to the heart of what’s really at stake here. The Digital Freedom Project, led by teenagers Noah Jones and Macy Neyland, argues that the ban violates the implied constitutional freedom of political communication. They’re right. Social media platforms, for all their flaws, have become essential venues for democratic discourse. By age 16, many young Australians are politically aware, engaged in climate activism, and participating in public debates. This ban silences them.

The government’s response, that child welfare trumps absolute freedom, sounds reasonable until you examine it closely. Child welfare is being invoked as a rhetorical trump card to justify what is essentially state paternalism. The government isn’t protecting children from objective harm; it’s making a value judgment about what information they should be allowed to access and what communities they should be permitted to join. That’s thought control, not child protection.

Moreover, the ban creates a two-tiered system of rights. Those over 16 can access platforms; those under cannot, regardless of maturity, need, or circumstance. A 15-year-old seeking LGBTQ+ support groups, mental health resources, or information about escaping domestic abuse is now cut off from potentially life-saving communities. A 15-year-old living in rural Australia, isolated from peers, loses a vital social lifeline. The ban is blunt force trauma applied to a problem requiring surgical precision.

The Privacy Nightmare

Let’s talk about the elephant in the digital room: data security. Australia’s track record here is abysmal. The country has experienced multiple high-profile data breaches, and now it’s mandating that platforms collect biometric data, government IDs, and behavioural information from millions of users, including adults who will need to verify their age to distinguish themselves from banned minors.

The legislation claims to mandate “data minimisation” and promises that information collected solely for age verification will be destroyed post-verification. These promises are worth less than the pixels they’re displayed on. Once data is collected, it exists. It can be hacked. It can be subpoenaed. It can be repurposed. The fine for violations, up to AUD 9.5 million, sounds impressive until you realise that’s pocket change for tech giants making billions annually.

We’re creating a massive honeypot of sensitive information about children and families, and we’re trusting companies with questionable data stewardship records to protect it. What could possibly go wrong?

The Global Domino Delusion

Proponents like US Senator Josh Hawley and author Jonathan Haidt praise Australia’s ban as a “bold precedent” that will trigger global reform. This is wishful thinking bordering on delusion. What Australia has actually created is a case study in how not to regulate technology.

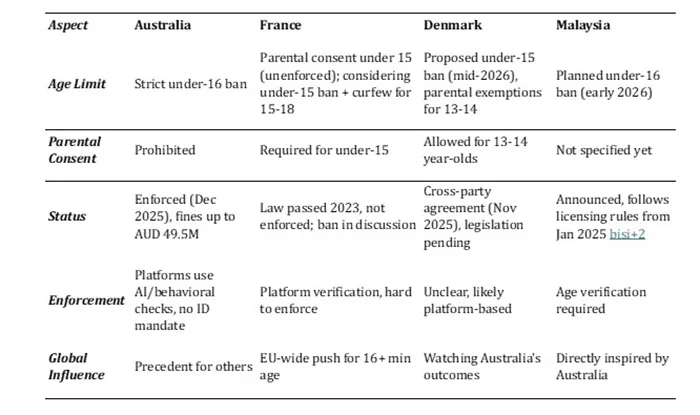

France, Denmark, and Malaysia are watching, but with notable differences. France’s model includes parental consent options. Denmark proposes exemptions for 13-14-year-olds with parental approval. These approaches recognise what Australia refuses to acknowledge: that blanket prohibitions fail to account for individual circumstances and family autonomy.

The comparison table in the document reveals the stark rigidity of Australia’s approach. It’s the only country attempting outright prohibition without parental consent. This isn’t leadership; it’s extremism. Other nations may cherry-pick elements of Australia’s approach while avoiding its most draconian features. (See Table)

The Real Solutions We’re Ignoring

Here’s what actual child protection would look like: holding platforms legally accountable for algorithmic harm, mandating transparent content moderation, requiring platforms to offer chronological feeds instead of engagement-maximising algorithms, funding digital literacy programmes in schools, properly resourcing mental health services for young people, and empowering parents with better tools to guide their children’s online experiences.

Instead, Australia has chosen the path of least intellectual effort: ban it and hope for the best. This is governance by bumper sticker, policy by panic.

Mia Bannister, whose son’s suicide has been invoked repeatedly to justify the ban, called parental enforcement “short-term pain, long-term gain” and urged families to remove devices entirely. But her tragedy, however heart-wrenching, doesn’t justify bad policy. Individual cases, no matter how emotionally compelling, are poor foundations for sweeping legislation affecting millions.

Conclusion: The Tyranny of Good Intentions

Australia’s social media ban is built on good intentions, genuine concerns about child welfare, and understandable frustration with unaccountable tech giants. But good intentions pave a very particular road, and this road leads to a place where governments dictate what information citizens can access based on age, where privacy becomes a quaint relic, and where young people are infantilised rather than educated.

The ban will fail on its own terms, teenagers will circumvent it, platforms will struggle with enforcement, and the mental health crisis will continue because it was never primarily about social media. But it will succeed in normalising digital authoritarianism, expanding surveillance infrastructure, and teaching young Australians that their rights are negotiable commodities.

When this ban inevitably fails, when the promised mental health improvements don’t materialize, when data breaches expose the verification systems, and when teenagers continue to access prohibited platforms through VPNs and workarounds, Australia will face a choice: double down on enforcement, creating an even more invasive surveillance state, or admit that the entire exercise was a costly mistake.

Smart money says they’ll choose the former. After all, once governments acquire new powers, they rarely relinquish them willingly. And that’s the real danger here, not that Australia will fail to protect children from social media, but that it will succeed in building the infrastructure for a far more intrusive state. The platforms may be the proximate target, but the ultimate casualties will be freedom, privacy, and trust.

Australia didn’t need a world-first ban. It needed world-class thinking. Instead, it settled for a world of trouble.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT, Malabe. The views and opinions expressed in this article are personal.)

Features

Sustaining good governance requires good systems

A prominent feature of the first year of the NPP government is that it has not engaged in the institutional reforms which was expected of it. This observation comes in the context of the extraordinary mandate with which the government was elected and the high expectations that accompanied its rise to power. When in opposition and in its election manifesto, the JVP and NPP took a prominent role in advocating good governance systems for the country. They insisted on constitutional reform that included the abolition of the executive presidency and the concentration of power it epitomises, the strengthening of independent institutions that overlook key state institutions such as the judiciary, public service and police, and the reform or repeal of repressive laws such as the PTA and the Online Safety Act.

The transformation of a political party that averaged between three to five percent of the popular vote into one that currently forms the government with a two thirds majority in parliament is a testament to the faith that the general population placed in the JVP/ NPP combine. This faith was the outcome of more than three decades of disciplined conduct in the aftermath of the bitter experience of the 1988 to 1990 period of JVP insurrection. The manner in which the handful of JVP parliamentarians engaged in debate with well researched critiques of government policy and actions, and their service in times of disaster such as the tsunami of 2004 won them the trust of the people. This faith was bolstered by the Aragalaya movement which galvanized the citizens against the ruling elites of the past.

In this context, the long delay to repeal the Prevention of Terrorism Act which has earned notoriety for its abuse especially against ethnic and religious minorities, has been a disappointment to those who value human rights. So has been the delay in appointing an Auditor General, so important in ensuring accountability for the money expended by the state. The PTA has a long history of being used without restraint against those deemed to be anti-state which, ironically enough, included the JVP in the period 1988 to 1990. The draft Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), published in December 2025, is the latest attempt to repeal and replace the PTA. Unfortunately, the PSTA largely replicates the structure, logic and dangers of previous failed counter terrorism bills, including the Counter Terrorism Act of 2018 and the Anti Terrorism Act proposed in 2023.

Misguided Assumption

Despite its stated commitment to rule of law and fundamental rights, the draft PTSA reproduces many of the core defects of the PTA. In a preliminary statement, the Centre for Policy Alternatives has observed among other things that “if there is a Detention Order made against the person, then in combination, the period of remand and detention can extend up to two years. This means that a person can languish in detention for up to two years without being charged with a crime. Such a long period again raises questions of the power of the State to target individuals, exacerbated by Sri Lanka’s history of long periods of remand and detention, which has contributed to abuse and violence.” Human Rights lawyer Ermiza Tegal has warned against the broad definition of terrorism under the proposed law: “The definition empowers state officials to term acts of dissent and civil disobedience as ‘terrorism’ and will lawfully permit disproportionate and excessive responses.” The legitimate and peaceful protests against abuse of power by the authorities cannot be classified as acts of terror.

The willingness to retain such powers reflects the surmise that the government feels that keeping in place the structures that come from the past is to their benefit, as they can utilise those powers in a crisis. Due to the strict discipline that exists within the JVP/NPP at this time there may be an assumption that those the party appoints will not abuse their trust. However, the country’s experience with draconian laws designed for exceptional circumstances demonstrates that they tend to become tools of routine governance. On the plus side, the government has given two months for public comment which will become meaningful if the inputs from civil society actors are taken into consideration.

Worldwide experience has repeatedly demonstrated that integrity at the level of individual leaders, while necessary, is not sufficient to guarantee good governance over time. This is where the absence of institutional reform becomes significant. The aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah in particular has necessitated massive procurements of emergency relief which have to be disbursed at maximum speed. There are also significant amounts of foreign aid flowing into the country to help it deal with the relief and recovery phase. There are protocols in place that need to be followed and monitored so that a fiasco like the disappearance of tsunami aid in 2004 does not recur. To the government’s credit there are no such allegations at the present time. But precautions need to be in place, and those precautions depend less on trust in individuals than on the strength and independence of oversight institutions.

Inappropriate Appointments

It is in this context that the government’s efforts to appoint its own preferred nominees to the Auditor General’s Department has also come as a disappointment to civil society groups. The unsuitability of the latest presidential nominee has given rise to the surmise that this nomination was a time buying exercise to make an acting appointment. For the fourth time, the Constitutional Council refused to accept the president’s nominee. The term of the three independent civil society members of the Constitutional Council ends in January which would give the government the opportunity to appoint three new members of its choice and get its way in the future.

The failure to appoint a permanent Auditor General has created an institutional vacuum at a critical moment. The Auditor General acts as a watchdog, ensuring effective service delivery promoting integrity in public administration and providing an independent review of the performance and accountability. Transparency International has observed “The sequence of events following the retirement of the previous Auditor General points to a broader political inertia and a governance failure. Despite the clear constitutional importance of the role, the appointment process has remained protracted and opaque, raising serious questions about political will and commitment to accountability.”

It would appear that the government leadership takes the position they have been given the mandate to govern the country which requires implementation by those they have confidence in. This may explain their approach to the appointment (or non-appointment) at this time of the Auditor General. Yet this approach carries risks. Institutions are designed to function beyond the lifespan of any one government and to protect the public interest even when those in power are tempted to act otherwise. The challenge and opportunity for the NPP government is to safeguard independent institutions and enact just laws, so that the promise of system change endures beyond personalities and political cycles.

by Jehan Perera

Features

General education reforms: What about language and ethnicity?

A new batch arrived at our Faculty again. Students representing almost all districts of the country remind me once again of the wonderful opportunity we have for promoting social and ethnic cohesion at our universities. Sadly, however, many students do not interact with each other during the first few semesters, not only because they do not speak each other’s language(s), but also because of the fear and distrust that still prevails among communities in our society.

A new batch arrived at our Faculty again. Students representing almost all districts of the country remind me once again of the wonderful opportunity we have for promoting social and ethnic cohesion at our universities. Sadly, however, many students do not interact with each other during the first few semesters, not only because they do not speak each other’s language(s), but also because of the fear and distrust that still prevails among communities in our society.

General education reform presents an opportunity to explore ways to promote social and ethnic cohesion. A school curriculum could foster shared values, empathy, and critical thinking, through social studies and civics education, implement inclusive language policies, and raise critical awareness about our collective histories. Yet, the government’s new policy document, Transforming General Education in Sri Lanka 2025, leaves us little to look forward to in this regard.

The policy document points to several “salient” features within it, including: 1) a school credit system to quantify learning; 2) module-based formative and summative assessments to replace end-of-term tests; 3) skills assessment in Grade 9 consisting of a ‘literacy and numeracy test’ and a ‘career interest test’; 4) a comprehensive GPA-based reporting system spanning the various phases of education; 5) blended learning that combines online with classroom teaching; 6) learning units to guide students to select their preferred career pathways; 7) technology modules; 8) innovation labs; and 9) Early Childhood Education (ECE). Notably, social and ethnic cohesion does not appear in this list. Here, I explore how the proposed curriculum reforms align (or do not align) with the NPP’s pledge to inculcate “[s]afety, mutual understanding, trust and rights of all ethnicities and religious groups” (p.127), in their 2024 Election Manifesto.

Language/ethnicity in the present curriculum

The civil war ended over 15 years ago, but our general education system has done little to bring ethnic communities together. In fact, most students still cannot speak in the “second national language” (SNL) and textbooks continue to reinforce negative stereotyping of ethnic minorities, while leaving out crucial elements of our post-independence history.

Although SNL has been a compulsory subject since the 1990s, the hours dedicated to SNL are few, curricula poorly developed, and trained teachers few (Perera, 2025). Perhaps due to unconscious bias and for ideological reasons, SNL is not valued by parents and school communities more broadly. Most students, who enter our Faculty, only have basic reading/writing skills in SNL, apart from the few Muslim and Tamil students who schooled outside the North and the East; they pick up SNL by virtue of their environment, not the school curriculum.

Regardless of ethnic background, most undergraduates seem to be ignorant about crucial aspects of our country’s history of ethnic conflict. The Grade 11 history textbook, which contains the only chapter on the post-independence period, does not mention the civil war or the events that led up to it. While the textbook valourises ‘Sinhala Only’ as an anti-colonial policy (p.11), the material covering the period thereafter fails to mention the anti-Tamil riots, rise of rebel groups, escalation of civil war, and JVP insurrections. The words “Tamil” and “Muslim” appear most frequently in the chapter, ‘National Renaissance,’ which cursorily mentions “Sinhalese-Muslim riots” vis-à-vis the Temperance Movement (p.57). The disenfranchisement of the Malaiyaha Tamils and their history are completely left out.

Given the horrifying experiences of war and exclusion experienced by many of our peoples since independence, and because most students still learn in mono-ethnic schools having little interaction with the ‘Other’, it is not surprising that our undergraduates find it difficult to mix across language and ethnic communities. This environment also creates fertile ground for polarizing discourses that further divide and segregate students once they enter university.

More of the same?

How does Transforming General Education seek to address these problems? The introduction begins on a positive note: “The proposed reforms will create citizens with a critical consciousness who will respect and appreciate the diversity they see around them, along the lines of ethnicity, religion, gender, disability, and other areas of difference” (p.1). Although National Education Goal no. 8 somewhat problematically aims to “Develop a patriotic Sri Lankan citizen fostering national cohesion, national integrity, and national unity while respecting cultural diversity (p. 2), the curriculum reforms aim to embed values of “equity, inclusivity, and social justice” (p. 9) through education. Such buzzwords appear through the introduction, but are not reflected in the reforms.

Learning SNL is promoted under Language and Literacy (Learning Area no. 1) as “a critical means of reconciliation and co-existence”, but the number of hours assigned to SNL are minimal. For instance, at primary level (Grades 1 to 5), only 0.3 to 1 hour is allocated to SNL per week. Meanwhile, at junior secondary level (Grades 6 to 9), out of 35 credits (30 credits across 15 essential subjects that include SNL, history and civics; 3 credits of further learning modules; and 2 credits of transversal skills modules (p. 13, pp.18-19), SNL receives 1 credit (10 hours) per term. Like other essential subjects, SNL is to be assessed through formative and summative assessments within modules. As details of the Grade 9 skills assessment are not provided in the document, it is unclear whether SNL assessments will be included in the ‘Literacy and numeracy test’. At senior secondary level – phase 1 (Grades 10-11 – O/L equivalent), SNL is listed as an elective.

Refreshingly, the policy document does acknowledge the detrimental effects of funding cuts in the humanities and social sciences, and highlights their importance for creating knowledge that could help to “eradicate socioeconomic divisions and inequalities” (p.5-6). It goes on to point to the salience of the Humanities and Social Sciences Education under Learning Area no. 6 (p.12):

“Humanities and Social Sciences education is vital for students to develop as well as critique various forms of identities so that they have an awareness of their role in their immediate communities and nation. Such awareness will allow them to contribute towards the strengthening of democracy and intercommunal dialogue, which is necessary for peace and reconciliation. Furthermore, a strong grounding in the Humanities and Social Sciences will lead to equity and social justice concerning caste, disability, gender, and other features of social stratification.”

Sadly, the seemingly progressive philosophy guiding has not moulded the new curriculum. Subjects that could potentially address social/ethnic cohesion, such as environmental studies, history and civics, are not listed as learning areas at the primary level. History is allocated 20 hours (2 credits) across four years at junior secondary level (Grades 6 to 9), while only 10 hours (1 credit) are allocated to civics. Meanwhile, at the O/L, students will learn 5 compulsory subjects (Mother Tongue, English, Mathematics, Science, and Religion and Value Education), and 2 electives—SNL, history and civics are bunched together with the likes of entrepreneurship here. Unlike the compulsory subjects, which are allocated 140 hours (14 credits or 70 hours each) across two years, those who opt for history or civics as electives would only have 20 hours (2 credits) of learning in each. A further 14 credits per term are for further learning modules, which will allow students to explore their interests before committing to a A/L stream or career path.

With the distribution of credits across a large number of subjects, and the few credits available for SNL, history and civics, social/ethnic cohesion will likely remain on the back burner. It appears to be neglected at primary level, is dealt sparingly at junior secondary level, and relegated to electives in senior years. This means that students will be able to progress through their entire school years, like we did, with very basic competencies in SNL and little understanding of history.

Going forward

Whether the students who experience this curriculum will be able to “resist and respond to hegemonic, divisive forces that pose a threat to social harmony and multicultural coexistence” (p.9) as anticipated in the policy, is questionable. Education policymakers and others must call for more attention to social and ethnic cohesion in the curriculum. However, changes to the curriculum would only be meaningful if accompanied by constitutional reform, abolition of policies, such as the Prevention of Terrorism Act (and its proxies), and other political changes.

For now, our school system remains divided by ethnicity and religion. Research from conflict-ridden societies suggests that lack of intercultural exposure in mono-ethnic schools leads to ignorance, prejudice, and polarized positions on politics and national identity. While such problems must be addressed in broader education reform efforts that also safeguard minority identities, the new curriculum revision presents an opportune moment to move this agenda forward.

(Ramya Kumar is attached to the Department of Community and Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Jaffna).

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

by Ramya Kumar

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoMembers of Lankan Community in Washington D.C. donates to ‘Rebuilding Sri Lanka’ Flood Relief Fund

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoPope fires broadside: ‘The Holy See won’t be a silent bystander to the grave disparities, injustices, and fundamental human rights violations’

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoPakistan hands over 200 tonnes of humanitarian aid to Lanka

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoUnlocking Sri Lanka’s hidden wealth: A $2 billion mineral opportunity awaits

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoArmy engineers set up new Nayaru emergency bridge

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoOfficials of NMRA, SPC, and Health Minister under pressure to resign as drug safety concerns mount

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoExpert: Lanka destroying its own food security by depending on imported seeds, chemical-intensive agriculture

-

Editorial7 days ago

Editorial7 days agoFlawed drug regulation endangers lives