Opinion

Adikaram, a man like no other

38th death anniversary of Dr E. W. Adikaram falls today

By Professor J.B. Disanayaka

It happened about sixty years ago. I was just a lad of seventeen, studying in grade eleven at Ananda College. As I walked past the small playground in the centre of the primary school premises, I caught the sight of a small-made man in our national dress, walking towards the Principal’s office. A senior whispered, “That’s Dr. Adikaram”. I had a good look at him, the new President of the BTS [Buddhist Theosophical Society], which looked after Ananda as the country’s main Buddhist educational institution.

I saw him again about ten years later, at the office of the Indian High Commission, where I had gone to get a visa to go to India to attend a religious conference in Darjeeling, organised by the Quakers, a society known for their opposition to violence and war. Dr. Adikaram was also there to get his visa to attend the very same meeting. It was my rare privilege to have a word with him. We left to India by air, from Ratmalana, on the full-moon day of Wesak, 1959.

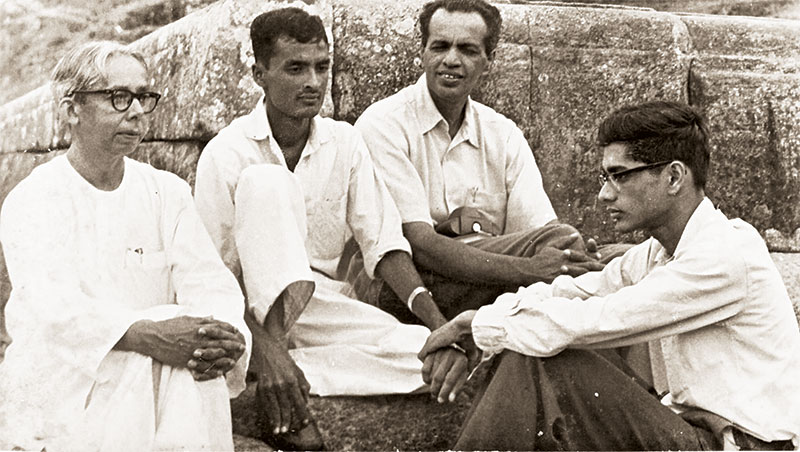

That was rather a coincidence, I thought, to go to India, the land of the Buddha’s birth, on the full-moon day of Wesak, which celebrates three events of His life — the Birth, the Enlightenment and the Passing Away. At Madras, we boarded the Howrah Express to Calcutta. There were four of us, all on our way to the Conference: Dr. Adikaram, Chris Pullenayagam, Chitra Wijesinha and me. I had the rare chance to sit next to Dr. Adikaram and chat with him for two long days!

Some of what he said took me by surprise. I just could not understand him when he said that he had seen my ‘astral body’ on three or four occasions when he was reading in his study at his house in Pagoda. Being a Theosophist, he was able to explain to me about ‘astral bodies’ but I simply could not take his word. It was so strange. So, I requested him to write all that on paper and he promised to do so on his return to Sri Lanka. And he did. It ran to about four or five foolscap pages!

As he sat in his study at Pagoda, he saw the glimpse of someone walking into his house. He came out of the room but there was none. This happened on a few more occasions and as days went by, he got a faint glimpse of the face of this strange man. He told all his friends, including Dr. Mahinda Palihawadana, the Principal of Ananda Sastralaya, whom he met in the morning at Pagoda, to keep track of this strange character. However, they saw no one that fits his frame. On his return from the Indian High Commission, he told his friends, “Well, I saw that man today!”

Quakers had chosen one of the most beautiful sites for their Conference, in a bungalow overlooking Mount Kanchenjunga, one of the world’s highest mountains in the Himalayan range, bordering India and Nepal. We spent about a week listening to lectures and discussing matters of ethical interest — on how to build a world without barriers. On my return to the Island, I contributed an article to the University journal and it was titled, ‘A World Without Barriers’.

Later, he took me to Adayar in Madras to listen to J. Krishnamurti at Vasanta Vihar. Krishnamurti was a man of stature, both physically and spiritually. I listened to him in earnest and found that his words made a lot of sense. ‘Conditioning’ is the word that made all the difference. We are all ‘conditioned’ by the world around us so much so that we fail to see reality. Our beliefs and dogmas, rites and rituals prevent us from seeing reality and all that prevents us from living in peace.

I had the chance to discuss some of these matters in detail with him intimately when I came to Pagoda to translate into Sinhala his PhD thesis, ‘Early History of Buddhism in Ceylon’. It was a wonderful model of research based on the study of Pali texts. He also made me study Pali so that I could do a better Sinhala translation. He assured to me that studying Pali was fun because he himself learnt it only after his first year at the University College, giving up science and mathematics.

I spent my vacations at Pagoda in the early sixties translating his book, but unfortunately, I could not finish the work because I had to leave on a Fulbright scholarship to California in 1963. I think he himself completed the translation but never forgot to acknowledge my contribution in his Sinhala Preface. Only a few knew it because in the Preface my name appears as ‘Jayaratna Banda Disanayaka’ of the Department of Sinhala of the University of Ceylon, Peradeniya!

Dr. Adikaram

Conditioning’, as Krishnamurti says, prevents our mind from seeing reality. So, we wanted to look at the nature of the mind itself, and we did a couple of experiments. I was at the Peradeniya campus and he was at Pagoda. We decided to set off a time on a particular day of the week to think about something, like rivers, mountains, animals and plants and so on. At the agreed upon time, I spent about five minutes, thinking about something in particular and jotted it down on a piece of paper. He did the same thing in his study at Pagoda. I posted my note to him and he sent his note to me. On many an occasion we have thought about the very same thing! Now, isn’t that strange!

Minds can communicate. Some call it telepathy. It still happens to me almost every day. I am writing this note on the fifteenth of March 2021. Let me tell you about a few strange coincidences that took place last month. On the ninth day of February I wanted to find out a little more about the Sinhala word san nam (brand name) and I thought of calling Achintya Bandara, a young lecturer in the Sinhala Department, because he said the other day that I am the san nam of Sinhala linguistics. In fifteen minutes, my mobile rings. It was Acintya Bandara.

On the 10th, Dr. Malini Endagama of the Mahavamsa Editorial Board wanted me to translate its fifth chapter into English. I was not interested and she wanted me to suggest another name. I thought of my friend, Austin Fernando, who was the Secretary to the President under a previous government, and who has written a book in English, titled ‘My Belly is White’. However, I was unable to contact him because I do not have his telephone number. A couple of hours later, Austin rang me to find out the meaning of a Sinhala word. What a bit of luck!

On the 13th of February, I wanted to write a short note on the Sinhala word kana kaesbaeva (blind sea-turtle). Then rings my mobile. “Sir, my name is Unantenne. What does kana kaesbeva viya siduren balanava mean? “Why on earth were we both thinking of the same blind mythical animal at the same time? What does all this mean? That the mind is strange. It was Dr. Adikaram who made me think about the unimaginable ways of the human mind.

His booklets in the Sitivili (Thoughts) series were all about the ways of the world and the ways of the mind. He always posed questions and wanted you to answer them along with him. Do you think or does thinking occur to you? Why do we get angry when others scold you? What do dreams tell you? Are there layers in the mind — deep and surface? Can the end justify the means?

I liked his style of writing in Sinhala — simple and straightforward. When I compiled a handbook on the correct usage in Sinhala, in 2018, I chose him as one of the seven modern writers who have a style of their own and who deserve to be imitated. He was also one of the first to write on Modern Science in Sinhala. He edited the first science magazine in Sinhala, titled Navina Vidya . He compiled a small English-Sinhala glossary for school children to help them learn science in Sinhala.

He was a man, a bachelor, who loved not women but nature — birds and flowers. At Pagoda I observed, every morning, how he kept food for the birds and watered his flower plants. Occasionally, he would call me and say, “Look how this flower smiles at me”. He allowed mice to hang around the garage as they pleased. Once he did not drive his car for a week because there were new-born little mice in the dicky!

Dr. Adikaram was a vegetarian not because it was a considered a sin (pav) to kill animals. “Even if someone were to tell me that it is a merit (pin) to kill animals, I shall not kill simply because it hurts animals”. He never visited the zoo because they had to kill many animals to keep other animals alive. Prof. Mahinda Palihawadana is still a vegetarian doing his best to make this a world where not only human beings but all beings can live in peace.

My interest was not in birds and plants but in language and culture. However, he was able to shift my attention to plants when he took me, along with Siri Palihawadana, who had an expensive camera, to the Peradeniya Botanical Gardens, to take pictures of certain trees for his textbooks on science. We sat under the shade of many trees and enjoyed our meals at leisure.

The 28th of December 1985 was a strange day. I was at the University of Edinburgh on a Commonwealth scholarship to study Applied Linguistics. On many a day, I would stop by the University Bookshop on Buccleuch Place to buy a book usually on Linguistics. However, when I browsed the books on the 28th, my attention was drawn to a book on Krishmanmurti and I was delighted to have got my hands on it.

I went back to my room and was reading Krishmnamurti, always thinking of Dr. Adikaram, who introduced me to him at Vasantha Vihar in Adayar. My telephone rang and it was Siri Palihawadana. “JB, I have some bad news to tell you. Doctor passed away a few hours ago.” Now isn’t that strange? To buy a book on Krishnamurti and read it, as Dr. Adikaram lay in his death bed?

Siri and his wife Lakshmi looked after Dr. Adikaram with utmost care and affection. I remember that he had a nursery of sandal-wood plants at the backyard and they were distributed to those who loved plants. As I write this note in the library of my daughter’s house, near the Sri Jayewardenepura campus, I see the young sandalwood tree in her garden, gifted to her by Ravi Palihawadana. It brings back memories of an unforgettable past, when Dr. Adikaram moulded my way of thought and my way of life.

Dr. Adikaram was like no other because different people saw him in different ways. He was an orientalist, with his knowledge of Pali and Sanskrit, a historian, who recorded the History of Early Buddhism in Ceylon educator who was the Principal of a leading Buddhist school, Ananda Sastralaya in Kotte, founder of the leading Buddhist girls’ school in Nugegoda, Anula Vidyalaya, science writer, and philosopher who did his best to mould the minds of the young to create a world without barriers.

Opinion

South Asian Regional Conference on State of Higher Education 2026 and Education Diplomacy

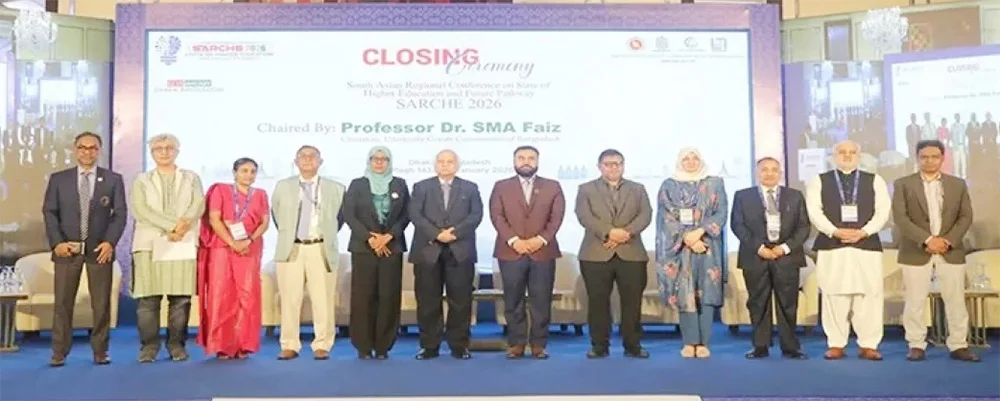

On the 15January 2026, the ‘Dhaka Declaration’ was adopted with eight strategic commitments, aimed at building a stable, inclusive, innovative and globally acceptable higher education system in the South Asian region at the third South Asian Regional Conference on State of Higher Education (SARCHE), 2026.

Advisors of the interim government, vice-chancellors of different public and private universities, scholars, researchers and diplomats were present at the third SARCHE 2026 Conference in Dhaka, emphasising the paramount importance of Education diplomacy.

The Nobel Laureate, Chief Adviser of the government, Professor Muhammad Yunus on 12th January 2026 inaugurated a three-day South Asian regional conference on higher education in Dhaka. The conference titled “South Asian Regional Conference on State of Higher Education and Future Pathway (SARCHE 2026)” organised by the Bangladesh government and World Bank funded Higher Education Acceleration and Transformation (HEAT) Project of the University Grants Commission (UGC) of Bangladesh.

Prof. Yunus’s call

Chief Adviser Professor Muhammad Yunus, has called upon the academics to align the education system with the youths’ expectations and aspirations and stressed on revival of the SAARC to enhance regional academic cooperation. “Today, I feel very excited that academics at the highest level could get together in Dhaka. It’s important that this is Dhaka. I hope you will have a chance to kind of review of the things that have happened in Dhaka in the past few months,” he said, referring to post-2024 July Uprising events in Bangladesh. Prof Yunus said review of those events will clarify what university education and education as a whole are really about, adding, this should be the core subject of discussion at the gathering.Highlighting the role of students in the 2024 uprising, he said, “Who are these young people that we are dealing with? They have their own mind. They stood up and raised their voices and brought down the ugliest fascist regime you could ever think of given their lives”.The Chief Adviser made the remarks while addressing the inaugural ceremony of the three-day “South Asian Regional Conference on State of Higher Education and Future Pathway (SARCHE 2026)” at a city hotel in Dhaka, Bangladesh. A total of 30 international representatives, including delegates from the United Kingdom, the Maldives, Malaysia, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka as well as representatives from the World Bank were represented in the event.”It would be a missed opportunity if you don’t spend some time on understanding what they did a few months back in this very city. What was their expectation? What was their aspiration? Why did they stand up in front of guns and give their lives knowingly it will happen,” the Chief Adviser said.To reflect the students’ motivation behind joining the uprising, he referred to school student Shaheed Shahriar Khan Anas’s letter, which he wrote to his mother before embracing the martyrdom, stating that it was his duty to take to the street with his friends, who were subjected to state-sponsored crackdown.Noting that the event was not a sudden outburst, Prof Yunus said it happened in Sri Lanka and in Nepal too, but it happened in a bigger way in Dhaka.

WB thanked for organisng event

He thanked the World Bank for organizing the conference, saying, “This was our responsibility to organize, but we failed. The World Bank has to step into make it happen”.Organizing such gatherings was part of the responsibility under the South Asian Association for Region-al Cooperation (SAARC), the Chief Adviser said, adding, but the SAARC as a word has been forgotten and “that’s a shame on us”. “This was supposed to be the idea of SAARC that we get together and make exchanges and learn from each other,” he said, noting his efforts since he has taken the responsibility as the Chief Adviser to revive the SAARC. “I am repeatedly reminding that we must get back to SAARC. That’s where our family belongs to. And I will not give up repeating that appeal to the governments of the region,” Prof Yunus said,Speaking about the forthcoming national elections and the referendum on February 12, he said the uprising tore everything apart and that the young people created their own July Charter to undo what the country was stuck with.

Referendum on Constitution

Chief Adviser said there would be a referendum to decide what the future constitution of Bangladesh should be, because they believed the root of the problems lay in the constitution. He said those issues were not taught in classrooms and questioned where universities stood in this reality. Noting that the young people have now formed their own political party, Prof Yunus said, “I’m sure some of them will get elected. “He called on educators to reflect on what education and university education should be in this very different world, warning that old ways of doing things are self-destructing and that change must happen quickly, just as the youth acted quickly during the July and August uprising.”So this is one issue, I hope this will be taken up seriously in this gathering where we are, what is being missed, how we can run and be in the front, rather than falling behind,” the Chief Adviser said.

He then said that the education system was not appropriate because it is job-oriented, adding, the system is designed around the idea that students must become suitable for jobs, and “If he or she fails to take a job, we think failure on the part of that student, not us”.Prof Yunus questioned whether the purpose of education is to prepare people for the job market. Human beings are not born as slaves and that each human being is a free person, he said, adding, jobs come from the tradition of slavery, where people work under orders for pay, which he equated with slavery.Stating that the young people who marched on the state refused to be slaves, he said, “So, what kind of education that you will be giving? This is a question I raise with you. You may dismiss it. You may pause for a while. But this is my point. Should we continue this education to create slaves? Turning creative beings into slaves, that’s a criminal job”. Prof Yunus said he translated creativity into entrepreneurship and argued that education should teach young people to be entrepreneurs rather than job seekers. He said young people should be told they are job creators and agents of change, driven by imagination, adding that imagination is the essence of human beings, and that people are born with enormous imagi-native power, which drove the youth to give their lives for the vision of a new Bangladesh.

Besides, representatives of UGCs and higher education commissions from SAARC member countries, vice-chancellors of universities from different countries, academicians and researchers took part in the conference.

Aim of the conference

According to the UGC, Bangladesh the conference has been organised aimed at elevating higher education in Bangladesh to a new height and further strengthen the UGC network among SAARC countries.

A total of eight sessions were held over the three-day conference. Emphasizing on “The Current State of Higher Education in South Asia: Governance, Quality and Inclusion” and “Research, Innovation, Sustainability and Social Engagement, Artificial Intelligence (AI) Integration, Digital Transformation and Smart Learning Ecosystems”, “Increasing Employment for Graduates and Industry–Academia collaboration”, “Future Pathways of Higher Education: Cooperation, Solidarity and Networking, “Stakeholder Dialogue on Higher Education Transformation: Voices of Civil Society”, and “Dialogue with Vice-Chancellors: the Context of the HEAT Project, gender issues in higher education will be held while the conference l ended following the adoption of the “Dhaka Higher Education Declaration”.

UGC, Bangladesh warns against fake foreign university branches in Bangladesh. Reports in various media outlets have highlighted several foreign universities, institutes are running unauthorized branch campuses, tutorial centers, and study centers across the country. The University Grants Commission (UGC) has cautioned students and parents against enrolling in three unauthorized foreign universities reportedly operating branch campuses in Bangladesh. According to the commission, American World University, USA; Trinity University, USA; and the Spiritual Institute of New York (State University) have no government or UGC approval to conduct academic activities in the country.

On the other hand, higher education has considered as a strategic necessity for the Maldives and called for enhanced regional cooperation, industry – academia collaboration, and impact – oriented research to support inclusive growth and resilience across the region.

While Pakistan has reached its greater heights in implementation of their AI policy, World bank is acting as a strong partner in developing these endeavors of regional partners.

Lessons to be learnt

We as a country has spent huge amount of expenditure in higher education, grants and research endeavors where majority of them have took place in western academic scenario. Our attitude as Sri Lankans do not wish to learn from regional partners and we highly embrace western based cultures and their development, while regional partners have emerged beyond Sri Lanka. Very few academia is passionately engaged in development initiatives while majority have violated bonds and residing in overseas lavishly having used government expenditure which should have spent on the public wellbeing of this Country. I wonder how many governments should take control of this paradise isle to understand this reality, still we are grappling with 17 universities under the Universities act with very few international student recruitments. The case of other State Universities cannot cater the increasing local demand as they need to keep their standards. In such a scenario admission of international students and their increasing demands are questionable? Our immigration do not facilitate as a separate compartment to facilitate international student recruitment like in Malaysia.

The government enacted the Private University Act in Bangladesh in 1992 and replaced in 2010. These laws were enacted to enable private universities to supplement the governments efforts in meeting the growing demand for higher education. Under the Act, private individuals, groups and philanthropic organizations are permitted to establish and operate self -financed, degree-awarding universities by fulfilling prescribed conditions. Due to rapid increase, the 2010 Act introduced Stricker provisions focused on quality assurance, accountability and good governance. It mandates statutory bodies such as Board of trustees, Syndicate and Academic Council and clearly defines their roles and responsibilities. The Vice chancellor serves as the chief executive and academic officer of the university and is the ex-officio member the Board of Trustees. The honorable president of Bangladesh act as the chancellor of all private universities and appoint key officials upon recommendations of the Board of trustees. The Act also mandates establishment of an accreditations council to ensure quality assurance UGC supervises and monitors private universities on behalf of the Ministry of Education, approves academic programs, curricula, prescribe minimum faculty qualifications and requires transparency through annual audited financial reporting.

However, many decades have gone and the Transnational education specifically in higher education in Sri Lanka is a struggle of Authority and Power. Many of the view that the Ministry of Higher Education does not cater the entire gamut of private Higher Education Institutes operating in Sri Lanka and do not address public issues. While UGC alone handles many of the public issues even in the transnational education with no authority in non-state sector. Hence, proper enactments under one umbrella need to be empowered for the sake of public. Sri Lankan practice is the Committees appointed to address public issues does not have genuine interest or knowledge to serve this sector rather depend on benefits derived.

Therefore, SARCHE 2026 has opened eyes of Sri Lanka on how the private sector should have healthy competition with public sector, while contributing massively to strengthen the economy.

Transnational Education in Sri Lanka

According to British Council reports on transnational Education,20224 and the SAARC regional Coordinator for the British Council was of the view that Sri Lanaka does not maintain a official repository for transnational education. The Company registrar or the Board of investment do not have a official repository which serves only for higher education purpose. There is no regulatory authority to address the agency problem engaged in transnational education where finally many have reported as unethical business practices.

While India, Pakistan, Maldives and Bangladesh massively invest on Transnational education to strengthen their economies we still do not have a national plan to address this with a regulatory mechanism with proper licensing, listing for Agents to operate in Sri Lanka in order to mitigate Education fraud.

Conclusion

There was a time when students who could not secure admissions to public universities turned to private universities as a last option. That really has changed significantly. Today, many students who qualify for public universities still choose private universities because they do not get admission to their preferred subjects. The primary reason is the freedom to study the subject of their choice. However, in Sri Lanka very few private entities provides a truly a university experience. While regional partners have improved beyond 100 in establishing private universities, still private public partnership in those countries are very best examples for Sri Lanka. According to the UGC,2023 Annual report there were 341,000 students enrolled across 110 private universities in Bangladesh, now has increased to 170 according to SARCHE,2026.

Pakistan maintains best examples of Artificial Intelligence models with World Bank Funding to their University System. University Business linkages in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh provide strong examples in Transfer of Technology. While Maldives will cater for the next round of SAARC conference on the state of higher education. They invite Sri Lanka along with regional partners for preparation of qualification framework with mutual recognition of qualifications with credit transfer facility. The “Dhaka declaration of Higher Education “was adopted at the SARCHE 2026, It intend to cooperate with regional partners in many aspects in Higher Education. With these concluding remarks it is high time to consider different aspects of higher education in the proposed reforms.

By Dr. Janadari Wijesinghe

Opinion

English as used in scientific report writing

The scientific community in the English-speaking world publishes its research findings using technical and scientific English (naturally!). It has its own particular vocabulary. Many words are exclusive for a particular technology as they are specialised technical terms. Also, the inclusion in research papers of mathematical and statistical terms and calculations is important where they support the overall findings.

There is a whole array of specialist publications, journals, papers and letters serving the scientific community world-wide. These publications are by subscription only but can easily be found in university libraries upon request.

Academics quote the number of their research papers published with pride. They are the status symbols of personal achievement par excellence! And most importantly, these are used to help justify the continuation of funding for the upcoming academic year.

Such writings are carefully crafted works of precision and clarity. Not a word is out of place. All words used are nuanced to fit exactly the meaning of what the authors of the paper wish to convey. No word is superfluous (= extra, not needed); all is well manicured to convey the message accurately to a knowledgeable, receptive reader. As a result, people from all around the world are using the Internet to access these research findings thus establishing the English language as a major form of information dissemination.

Reporting is best when it is measurable and can be quantified. Figures mean a lot in the scientific world. Sizes, quantities, ranges of acceptance, figures of probability, etc., all are used to lend authority to the research findings.

Before a paper can be accepted for publication it must be submitted to a panel for peer review. This is where several experts in the subject or speciality form a panel to assess the work and approve or reject it. Careers depend on well-presented reports.

Preparation Before Starting Research

There is a standard procedure for a researcher to follow before any practical work is done. It is necessary to evaluate the current status of work in this subject. This requires reading all the relevant, available literature, books, papers, etc., on this subject. This is done for the student to get ‘up to speed’ and in tune with the preceding research work in this field. During this process new avenues for research and investigation may open up for investigation.

Much research is done incorporating the ‘design of experiments’ statistical approach. Research these days rely heavily on statistics to prove an argument and the researcher has to be familiar and conversant with these statistical techniques of inquiry and evaluation to add weight to his or her findings.

We are all much richer due to the investigations done in the English-speaking world by the investigative scientific community using English as a tool of communication. In scientific research, the best progress in innovation, it seems, is when students can all collaborate. Then the best ideas develop and come out.

Sri Lankans should not exclude themselves from this process of knowledge creation and dissemination. Sri Lanka needs to enter this scientific world and issue its own publications in good English. Sri Lanka needs experts who have mastered this form of scientific communication and who can participate in the progress of science!

The most wonderful opportunities open up from time to time for graduates of the STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) mainly in companies using modern technology. The reputation of Sri Lanka depends on having a horse in this race – quite apart from the need to provide suitable careers for its own population. People have ambitions and need to be able rise up intellectually and get ahead. Therefore, students in the STEM subjects need to be able to read, analyse and compare several different research papers, i.e., students need to have critical thinking skills – in English. Often, these skills have to be communicated. Students need to be able to write to this high standard of English.

Students need to be able to put their thoughts on paper in a logical, meaningful way, their thoughts backed up by facts and figures according to the principles of the academic, research world. But natural speakers of English have difficulties in mastering this type of English and doing analyses and critical thinking – therefore, it must be multiple times more difficult for Sri Lankans to master this specialised form if English. Therefore, special attention needs to be paid to overcoming this disadvantage.

In addition, the researcher needs to have knowledge of the “design of experiments,” and be familiar with everyday statistics, e.g., the bell curve, ranges of probability, etc.

How can this high-quality English (and basic stats) possibly be taught in Sri Lanka when most campuses focus on the simple passing of grammar exams?

Sri Lanka needs teachers with knowledge of this advanced, specialist form of English supported with statistical “design of experiments” knowledge. Secondly, this knowledge has to be organised and systematized and imparted over a sufficient time period to students with ability and maturity. Over to you NIE, Maharagama!

by Priyantha Hettige

Opinion

Sri Lanka, the Stars,and statesmen

When President J. R. Jayewardene stood at the White House in 1981 at the invitation of U.S. President Ronald Reagan, he did more than conduct diplomacy; he reminded his audience that Sri Lanka’s engagement with the wider world stretches back nearly two thousand years. In his remarks, Jayewardene referred to ancient explorers and scholars who had written about the island, noting that figures such as Pliny the Elder had already described Sri Lanka, then known as Taprobane, in the first century AD.

Pliny the Elder (c. AD 23–79), writing his Naturalis Historia around AD 77, drew on accounts from Indo-Roman trade during the reign of Emperor Claudius (AD 41–54) and recorded observations about Sri Lanka’s stars, shadows, and natural wealth, making his work one of the earliest Roman sources to place the island clearly within the tropical world. About a century later, Claudius Ptolemy (c. AD 100–170), working in Alexandria, transformed such descriptive knowledge into mathematical geography in his Geographia (c. AD 150), assigning latitudes and longitudes to Taprobane and firmly embedding Sri Lanka within a global coordinate system, even if his estimates exaggerated the island’s size.

These early timelines matter because they show continuity rather than coincidence: Sri Lanka was already known to the classical world when much of Europe remained unmapped. The data preserved by Pliny and systematised by Ptolemy did not fade with the Roman Empire; from the seventh century onward, Arab and Persian geographers, who knew the island as Serendib, refined these earlier measurements using stellar altitudes and navigational instruments such as the astrolabe, passing this accumulated knowledge to later European explorers. By the time the Portuguese reached Sri Lanka in the early sixteenth century, they sailed not into ignorance but into a space long defined by ancient texts, stars, winds, and inherited coordinates.

Jayewardene, widely regarded as a walking library, understood this intellectual inheritance instinctively; his reading spanned Sri Lankan chronicles, British constitutional history, and American political traditions, allowing him to speak of his country not as a small postcolonial state but as a civilisation long present in global history. The contrast with the present is difficult to ignore. In an era when leadership is often reduced to sound bites, the absence of such historically grounded voices is keenly felt. Jayewardene’s 1981 remarks stand as a reminder that knowledge of history, especially deep, comparative history, is not an academic indulgence but a source of authority, confidence, and national dignity on the world stage. Ultimately, the absence of such leaders today underscores the importance of teaching our youth history deeply and critically, for without historical understanding, both leadership and citizenship are reduced to the present moment alone.

Anura Samantilleke

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoSri Lanka, the Stars,and statesmen

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoClimate risks, poverty, and recovery financing in focus at CEPA policy panel

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoHayleys Mobility ushering in a new era of premium sustainable mobility

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoAdvice Lab unveils new 13,000+ sqft office, marking major expansion in financial services BPO to Australia

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoArpico NextGen Mattress gains recognition for innovation

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoAltair issues over 100+ title deeds post ownership change

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoSri Lanka opens first country pavilion at London exhibition

-

Business13 hours ago

Business13 hours agoSLIM-Kantar People’s Awards 2026 to recognise Sri Lanka’s most trusted brands and personalities