Features

Educational reforms Sri Lanka demands today for a brighter tomorrow

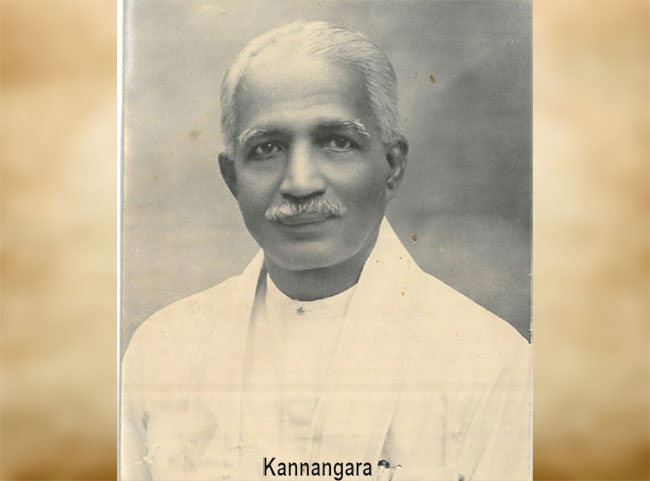

As a Sri Lankan who benefitted from free education, I feel honoured and privileged to deliver this Dr. C.W.W. Kannangara Memorial Oration, the 32nd in the lecture series inaugurated in 1988 on the twentieth anniversary of his demise.

I am well aware of the gravity of this task, particularly when considering the impressive stature of previous orators, often beneficiaries of free education themselves. The current economic, political and social crisis adds a further layer of complexity to the context in which this oration is delivered today. Within that backdrop, and with a keen awareness of the responsibility placed on my shoulders, I shall humbly endeavour to do justice to this task.

I am a medical practitioner by profession; however, I have spent most of my life sharing knowledge with friends, colleagues and students, as a teacher. This student-teacher reincarnation has been the focus and foundation of my entire life. Taking on the task of teaching arithmetic to my elder sister at the age of fifteen was my first venture into teaching. While waiting for entrance to the Medical Faculty, during the five years of university and well after that, I spent a considerable proportion of my time as a teacher. I had supported a number of students to pass their examinations for free, and as word spread of my skill in getting students through examinations, so many requests came in that I ended up establishing and running a private education institute named ‘Vidya Nadi’. This was more because I could not avoid the responsibility than for economic reasons. Most of those students are very prominent members of society today. The life lessons I obtained from being a teacher were significant and serve me to this day. Since then, I spent most of my life teaching and carrying out research in local and foreign universities, so much so that I would like to note that I have spent more time as a teacher and a researcher than as a doctor.

Within the same time frame, as a socially sensitive and politically informed person, as well as a medical student, I was also an activist who fought to defend free education, which gave me a different perspective on education. The complex and challenging context of today forces me to revisit this past and to re-examine the path we took in our younger days.

Against this complex background, my approach to this lecture today is based on two contrasting viewpoints Sri Lankan society holds on free education and the Kannangara legacy. Professor Narada Warnasuriya, who is a dear and well-respected teacher to me, during his Kannangara Memorial Lecture delivered in 2008, explained these two viewpoints as follows:

One group sees the Kannangara legacy in a single dimension, as a valuable basis for further expanding access to education, which also helps preserve fairness and social justice. They see it as a keystone of a just and conflict-free sustainable society.

The second group acknowledges that the Kannangara reforms had a major impact on bringing about a positive societal, and social transformation, but considers such changes irrelevant in the present context of a globalized free market economy. Professor Warnasuriya states that this group sees the Kannangara reforms as ‘a sacred cow, an archaic barrier to development, which stands in the way of building a successful knowledge-based economy’.

As an individual examining the status of education with an analytical mind, I do not wish to align myself with either of these groups exclusively, and decided to deliver this lecture from a neutral position, considering the positive and negative aspects of both viewpoints. This oration is therefore entitled Educational reforms Sri Lanka demands today for a brighter tomorrow and I plan to expand the discussion on Kannangara Legacy

I should also like to clarify that I prefer to refer to this as ‘our lecture’ rather than ‘my lecture’, because this lecture necessarily contains the views of a large group of like-minded people who work together with me as a team, on educational reforms.

Most of the facts forming the basis of this lecture are extracted from the recently published thirty-ninth (one-hundred page) special issue of the trilingual journal ‘Gaveshana’, entitled: ‘Educational reforms the country demands to create a productive citizen adaptable to the modern world’. This edition of Gaveshana is particularly significant in that it was published in the form of a research publication based on original data, and secondly, since a cross-section of educationists and officials from the Education sector who are directly involved with Sri Lankan educational reforms contributed to this publication, as did external experts who brought in a broader, societal viewpoint.

As someone who strongly believes that ‘a person alone cannot win a battle against the deep seas’, I would like to note that we are in an era in which not one but thousands of Dr. C.W.W. Kannanagaras are needed. Furthermore, it is important to note that educational reforms should not take a top-down approach but aim to incorporate the requirements and viewpoints of the beneficiaries of such reforms as honoured stakeholders: the knowledgeable student community, teachers and the general public. Such reforms should be informed by a regular feed-back loop, follow-up and grass-roots research. Educational reforms must be a dynamic process, not a static one, and follow-up research should be used to change not only the direction, but also the content of the reforms, if and when necessary.

This is the responsibility history vests on our shoulders, and in order to do justice to this obligation, I am deeply grateful to the Director General of the National Institute of Education and the staff of its Research and Planning Department for giving me this opportunity.

I was influenced early in life to believe the Stalinist concept of It is not heroes that make history, but history that makes heroes. But today, I am of the firm opinion that there are individuals who make constructive (or destructive) contributions to history. Dr. C.W.W. Kannangara is undoubtedly such a person who has left a lasting and positive contribution a hero that did change history, and it is therefore necessary to study not only the history he bequeathed but the person himself.

Who is Dr C.W.W Kannangara?

Dr. Christopher William Wijekoon Kannangara was born on October 13, 1884, at Randombe village, Ambalangoda. The third child in his family, he lost his mother early in life when his mother died giving birth to a younger brother. His father had five children from his first marriage and four from his second marriage. Although he was well looked after by his stepmother, he had faced the sad fate of losing his mother early in life. His father was a Buddhist, but his mother was a devotee of the Church of England. Christopher William Wijekoon was therefore baptized as a Christian although he formally converted to Buddhism as an adult in 1917. It was, as many of his closest Christian friends said, an act of wisdom and not a political act. Moreover, he learned Sinhala and Pali languages ??as well as Buddhism from his locality and environment.

He was a bright student, initially at Ambalangoda Wesleyan College. At its triennial prize-giving ceremony, he received the attention of accomplished mathematics teacher and the then Headmaster of Richmond College, Galle, Father D.H. Darrell.

Father Darrell had graduated from the Cambridge University, England with a first-class degree in mathematics. It is documented that Father Darrell had said to young Kannangara you will have to bring a heavy cart to take home the prizes you have won’. Father Darrell had then asked the Principal of Wesleyan College to prepare young Kannangara for the open scholarship examination at Richmond College. It is evident that it was this meeting with Father Darrell, the Headmaster of Richmond College at the age of 14 years, that turned out to be the pivotal point of Dr. Kannangara’s life.

Young student Kannangara subsequently won this scholarship, enabling him to attend Richmond College with free tuition, room and board. My belief is that this full scholarship established the foundation for the gift of free education that he later bequeathed to the nation.

He had to face further adversity in his life when his father lost his job and his pension after thirty years of service, leading to significant financial difficulty for his family. I would like to emphasise on, particularly to the young generation of today, the importance of recognising how his life was not cushioned in comfort, but was one of achieving greatness despite hardship and difficulty.

He was a bright student who excelled not only in studies but also in sports. He passed the Cambridge Junior Examination with honours and came first in the country and in the British Empire in Arithmetic. He was the captain of the cricket team, played in the football team and was a member of the debating team. He was also the lead actor in the school’s production of The Merchant of Venice. He was not a ‘bookworm’, but also excelled in extracurricular activities. Sadly, it is necessary to note the significant difference between the life of Dr. Kannangara as a student and the lives of the majority of children today.

At the time, the only option available for studying abroad was a government scholarship. Twelve Richmondites sat this examination, but he was unable to secure a scholarship, thus losing the opportunity to study at a foreign university. He chose instead to study law at the Sri Lanka Law College. Father Darrell, his mentor, however, requested young Kannangara to stay on at the school as the mathematics teacher and senior housemaster of the student hostel. He accepted and fulfilled this responsibility until the untimely death of Father Darrell, after which he moved to Colombo and embarked on his legal education. During this period, he also worked as a part-time teacher at Prince of Wales College, Wesley College and Methodist College.

By 1910, he had qualified as a lawyer and returned to Galle to start his legal career. He focused on civil law, carried on social service activities simultaneously and entered formal politics in 1911, supporting Mr. Ponnambalam Ramanathan. He actively campaigned for Mr. Ramanathan when he successfully contested in the 1917 elections for the Legislative Assembly, and the two ended up establishing a close friendship thereafter. He was an eloquent speaker at the establishment of the Ceylon National Council in 1919, expounding on its objectives to direct the country and the people towards a life of political freedom with equal rights and independence.

The pivotal moment of his political life came about when he was elected to the Legislative Assembly in 1923, representing the Southern Province. He was then elected as the President of the Ceylon National Congress in 1930 and in 1931, he became Sri Lankas first Minister of Education, after being elected to the State Council of Ceylon from the Galle district. He was elected the first chairman of the Executive Committee for Education with an overwhelming majority. He was re-elected to the same position in 1936 and held that position for 16 years.

The extent of the struggles and sacrifices Dr. Kannangara underwent to achieve free education should also be evaluated in the context of the political environment of the time. He entered politics at the time of Sri Lanka achieving universal franchise. The State Council at the time had 46 members and seven ministerial portfolios were available for elected members, one of these was the education portfolio.

Prof Athula Sumathipala delivering the Kannangara memorial lecture

He was conferred an honorary doctorate in law at the first convocation of the University of Ceylon under the auspices of the Vice-Chancellor Sir Ivor Jennings in 1942. It was in 1945 that he managed to finally achieve the passage of parliamentary bill to establish free education in the country. And yet, Dr. Kannangara, who was venerated as the Father of Free Education, was defeated at the first national parliamentary elections held in 1947. It is time to question if this defeat was a personal one or if it was a defeat of the entire Sri Lankan nation. He lost the election to a Mr. Wilmot. A. Perera, who was backed by wealthy individuals in the United National Party and with the support of the socialist camp as well. Even the Communist Party of Sri Lanka worked against Dr. Kannangara’s election campaign.

Time does not permit an in-depth discussion of the factors leading to the election defeat of a person who achieved societal change at such a significant scale, however, I do consider this one of the greatest ironies in Sri Lankan political history.

He was re-elected as a member of parliament in 1952, and was offered the Local Government portfolio. He was however denied the education portfolio, likely due to the influence of powers that be who wished to prevent further educational reforms by Dr. Kannangara. He retired from politics in 1956 when he turned seventy-two, but served as a member of the National Education Commission, indicating his commitment towards the education of the nation, which was beyond politics.

At the time of his entry into politics, Dr. Kannangara was quite prosperous economically, having started his career as a lawyer in 1923. Twenty years of holding a ministerial role, and forty years of public service, which is indeed the basis of politics, had led to a loss of financial stability by the time he retired. He showed by example that politics should not be a money-making mechanism. The Sri Lankan government offered him a one-time stipend of Rs. Ten thousand in 1963, a substantial amount of money at the time. Considering his health needs, he was offered a monthly living allowance of Rs.500/- in 1965, and this was subsequently increased to Rs.1000/- per month.

This great son of Sri Lanka, considered the Father of Free Education, passed away on 29th September 1969 without receiving much attention from the nation.

I think it is important to highlight a factor pointed out by Senior Professor Sujeewa Amarasena when he delivered the 28th Kannangara Memorial Oration. Professor Amarasena is a proponent of the second viewpoint Professor Warnasuriya mentions, i.e., those who acknowledge that the Kannangara reforms had a major impact on bringing about a positive societal, and social transformation, but consider such changes irrelevant in the present context of a globalized free market economy.

Senior Professor Sujeewa Amarasena said, today every political party, every organization connected to education, every trade union in the government or private sector and every individual who has had some education would come forward to protect free education as a social welfare intervention. The entire country and political parties with allied student movements are in a vociferous dialogue always talking about free education without really giving the legend Dr. CWW Kannangara his due place in this dialogue. I have not seen or heard a single University or a student organization in this country commemorating Dr. CWW Kannangara on his birthday though all of them are vociferous fighters to protect free education. Hence today late Dr. CWW Kannangara is a forgotten person as stated by Mr. KHM Sumathipala in his book titled History of Education in Sri Lanka 1796 to 1965. I would like to add to that and say that not only he is a forgotten person today, but even his vision has been misinterpreted, misdirected, distorted and partly destroyed by some people who benefitted from free education.

The irony of history extends further: at a time when school education was unavailable to the entire generation of children in Sri Lanka during the Covid-19 pandemic, many teachers were committed to providing an education to children via distance / online education, as it was the only viable option, albeit flawed in some ways. Some union leaders, in the guise of so-called trade union action, worked to obstruct such teachers from providing online education. Given that all trade union leaders are beneficiaries of free education, it has to be questioned if it is not the worst mockery in the history of free education that teachers rights were considered a priority, over the right of students to obtain an education. This tragedy raises multiple questions: has the expectation that widening access to education would create selfless citizens who think beyond personal gain and fulfil their responsibilities to the nation not been realised? Did the generation who benefited from the Kannangara reforms shirk their responsibilities in the post-Kannangara era? Or is it simply that the agenda for national benefit has been rendered secondary to narrow political gains?

Features

Picked from the Ends of the Earth he became the Pope of the Peripheries

“You know that it was the duty of the Conclave to give Rome a Bishop. It seems that my brother Cardinals have gone to the ends of the earth to get one, but here we are.” That was then Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio from Buenos Aries, Argentina, and newly elected as Pope Francis on 13 March 2013, addressing the throng of faithful Christians and curious tourists from the papal balcony of Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome. “Sacristy sarcasm,” as a Catholic writer has aptly described it, was one of many endearing attributes of Pope Francis who passed away on Easter Monday after celebrating the resurrection of Christ the day before. Francis was the first Jesuit to become Pope, the first Argentinian Pope, and the first Pope from outside of Europe in over a 1,000 years.

He broke conventions from the outset, preferring the plain white cassock and his personal cross to richly trimmed capes and gold crucifixes, and took the name Francis not after any preceding Pope but after Saint Francis of Assisi, the 13th century Italian Catholic friar, one of Italy’s patron saints and the Church’s patron of the environment. Born to immigrant Italian parents in Argentina, the quintessential periphery of the modern world order, Pope Francis became the Pope of the world’s migrants, its peripheries, and its environment. The protection of migrants, the theme of the peripheries and the stewardship of the environment have been the defining dimensions of the Francis papacy.

Addressing the cardinals before the Conclave, Francis called on the Church to “come out of herself and to go to the peripheries, not only geographically, but also the existential peripheries”. Francis was the first Pope to break the Eurocentric matrix of the Church. His predecessor from Germany, Pope Benedict XVI, had been an unabashed Europhile who had expressed concerns over non-Christian Turkey joining the European Union and was known for his views alluding to violent aspects of Islam.

In contrast, Francis dared to take the Church “beyond the walls” and to reach out to humanity as a whole. His October 2020 encyclical, “Fratelli Tutti,” (Fraternity and Social Friendship), was an inspired call to fight the dominant prejudice of our time targeting Muslims. Muslims and Christians in the Middle East are among the more vocal in sharing their grief at his passing. He has consistently called for unity in their battered lands, “not as winners or losers, but as brothers and sisters”. During the devastation of Gaza after October 2023, he kept close contact with priests in Gaza and practically called them every night until his recent illness.

Within the Church, Francis recast the College of Cardinals to make it globally more representative and reduce its European dominance. The 135 cardinals under 80 years who will conclave to elect the Francis’s successor include 53 cardinals from Europe, 23 from Asia, 20 from North America, 18 each from South America and Africa, and three from Oceania.

His first encyclical in 2015, Laudato Si’” (“Care for our Common Home”) on the environment, was again a first for the Church, and it became the moral manifesto for climate change action both within and outside the Church, and a catalyst for consensus at the historic 2015 Paris Climate Change Conference. The encyclical focuses on the notion of ‘integral ecology’ linking climate crisis to all the social, political and economic problems of our time. The task ahead is to take “an integrated approach” for “combatting poverty, “protecting nature” and for “restoring dignity to the excluded”.

The 12 years of the Francis papacy were also years of historical global migration from the peripheries and the social and political backlashes at the centre. In one measure of the problem, there were 51 million displaced people in the world in 2013 when Francis became Pope, but the number more than doubled to 120 millions by 2024. Pope Francis countered the political backlash against migration by projecting compassion for the migrants and the marginalized as a priority for the Church. He famously rebuked Trump in 2015 when Trump was foraying into presidential politics and touted the idea of a “big, beautiful wall” at the US-Mexican border, and said that building walls “is not Christian.”

In January, this year, Pope Francis called out US Vice President JD Vance’s flippant interpretation of the Catholic concept of “ordo amoris” (the order of love or charity) to justify Trump’s restrictive immigration policies. Vance, a Catholic convert since 2019, had suggested that love and charity should first begin at home, could then be extended to the neighbour, the community, one’s country, and with what is left to see if anything can be done for the rest of the world. America first and last, in other words.

The Pope’s rejoinder was swift: “Christian love is not a concentric expansion of interests that little by little extend to other persons and groups. The true ordo amoris that must be promoted is that which we discover by meditating constantly on the parable of the ‘Good Samaritan,’ that is, by meditating on the love that builds a fraternity open to all, without exception.” The Pope went on to condemn the Trump Administration’s conflation of undocumented immigrant status with criminality to justify their forced deportation out of America.

Papacy and Modernity

The Catholic Church and the papacy are nearly 2,000-year old institutions, perhaps older and more continuous than any other human institution. The papacy has gone through many far reaching changes over its long existence, but its consistent engagement with the broader world including both Christians and non-Christians is a feature of late modernity. The Catholic journalist Russell Shaw in his 2020 book “Eight Popes and the Crisis of Modernity”, provides an overview of the interactions between the popes of the 20th century – from Pius X to John Paul II – and the modern world in both its spiritual and secular dimensions.

The dialectic between the popes and modernity actually began with Pope Leo XIII of the 19th century, whose 1891 encyclical Rerum Novarum was a direct response to the spectre of socialism in the late 19th century and elevated property rights to be seen as divine rights located beyond the pale of the state. As I have written in this column earlier, in Fratelli Tutti, Pope Francis falls back on anterior Christian experiences to declare that “the Christian tradition has never recognized the right to private property as absolute or inviolable and has stressed the social purpose of all forms of private property.” He also moved away from the Church’s traditional privileging of individual subsidiarity over the solidarity of the collective to emphasizing the value of solidarity, decrying the market being celebrated as the panacea to satisfy all the needs of society, and calling for strong and efficient international institutions in the context of globalized inequalities.

Popes of the 20th century have grappled with both secular and spiritual challenges through some really tumultuous times including two world wars; the rise and fall of fascism and Nazism, not to mention communism; the liberation of colonies as nation states; economic depressions and recessions; the sexual revolution; and, in our time, massive migrations, climate change, never ending conflicts, and most of all the growing recognition of the centrality of the human person including the recognition and realization of human rights.

In varying ways, the popes have been advocates of peace and provided moral and material support to resolving conflicts around the world. Pope Francis has been more engaged and more ubiquitous than his predecessors in using the papacy to good effect. His Argentinian background gave him the strength and a unique perspective to take on current political issues unlike the Italian popes of the 20th century; the Polish Pope John Paul II who had quite a different experiential background and therefore a different agenda; or Benedict XVI who was mostly a German theologian.

A pope’s ultimate legacy largely depends on what he did with the Church that he inherited, both as an institution and as an agency, and what he leaves behind for his successor. As the Catholic Historian Liam Temple, at Durham University, has observed in his obituary, “Pope Francis embodied a tension at the heart of Catholicism in the 21st century: too liberal for some Catholics and not liberal enough for others. As such, his attempts at reform necessarily became a fine balancing act. History will undoubtedly judge whether the right balance was struck.” At the same time, Pope Francis’s broader legacy could be that he irreversibly brought the spatial and social peripheries of the world to the centre of papacy in Rome.

by Rajan Philips

Features

LESSONS FROM MY CAREER: SYNTHESISING MANAGEMENT THEORY WITH PRACTICE

Part 10

Wrapping up in Japan

I was sorry that my wonderful stay in Japan was coming to an end. The Industrial and Systems Engineering course had come to a close. My wife, too, joined me for the last week. The Asian Productivity (APO) organizers of the course were very gracious in inviting her to the closing ceremony and the farewell party.

All the participants were excited about putting what we had learned into practice. In fact, we had to submit a work programme we hoped to implement upon returning to our home countries. The APO and AOTS (Association for Overseas Technical Scholarship) staff left no stone unturned to give us theoretical and practical knowledge over these three months. We were so grateful to them.

My wife and I had planned some interesting sightseeing, but nothing went according to plan. We had planned some excursions from the day after the course finished, but the TV announced early morning about an impending typhoon, advising everyone to stay indoors. The joke by the Philippines participants that “the only things they export to Japan are typhoons” came true.

Most typhoons originate near the Philippines and head towards Japan mainly in September. The “all clear signal” came only in the afternoon. The other trip we went on was to the amusement park at Lake Yamanaka at the foot of Mount Fuji. It was a disaster because it was the sunniest Saturday of that summer, and everyone was going in the same direction. The usual two-hour trip became six hours, and by the time we got to the park, it was time to leave on our pre-booked return bus. We just had time for a short paddle boat ride.

Stopover in the Philippines

As I had mentioned in an earlier episode, The Ceylon Tyre Corporation, where I was the Industrial Engineer, had a technical collaboration with BF Goodrich, a global tyre manufacturer with plants in several countries. They arranged for me to visit their plant near Manila.

If my memory is correct, I recall that the Sri Lanka rupee was stronger than the Philippine peso at that time. We were picked up at the airport by the Plant Manager, and the first thing he told my wife was, “Don’t ever wear that chain when you go out”. He told me, “Never wear that wristwatch when you go out”.

On the way to the hotel, the police checked the car. We were asked to get out and were checked. Immediately, I formed a negative opinion of the country. Apparently, there were some bomb explosions in the city. Marcos’s term was coming to an end. The general gossip was that Marcos had engineered the bomb blasts so that he could continue with Martial Law.

In 1980, Sri Lanka had no checkpoints, nor was anyone checked. When I entered a mall in the evening, the security guard thoroughly checked my wife’s handbag and my camera case. I was surprised at these checks. A couple of years later, Sri Lanka was in the same boat.

The factory visit was great. I was struck by the comparison that at the Ceylon Tyre Corporation, we made 1,000 standard tyres with 2,000 employees, while at the BF Goodrich factory they made 2,000 tyres with 1,000 employees. Our labour productivity was awful. However, I learned a few things that we could improve back home.

Back at work

Returning to the factory and resuming my job as the Industrial Engineer, I implemented some changes. Still, I found a lot of resistance from many others. I was determined to implement the famous Japanese “Quality Circles”, where non-executive employees are trained and empowered to analyze production and quality problems and proceed in a systematic way to find the root causes, generate solutions and implement them with management approval.

BF Goodrich New York sent a set of success stories and failures of Quality Circles from the USA and Europe. The year 1980 was the peak of the popularity of Quality Circles, and almost every journal, whether it was Engineering, Accountancy, Personnel Management, or Management, had articles about this new technique from the mystical Far East.

I wasn’t making much progress with Quality Circles, and a colleague told me it would never succeed because the Chairman was a non-believer in the participative style of management. The workers immediately erased the factory floor lines I managed to paint. Change was not favoured.

I discussed my frustrations with my immediate boss. I explained my desire to implement many new methods I learned in Japan and expected him to remove these obstacles. He pondered and said, “OK. Give me three months”. After three months, I had not noticed anything new or any change in attitude, so I confronted my boss again. He leaned back in his chair, smiled and said, “When I completed my MSc and returned, I faced a similar situation, but in three months, my enthusiasm had vanished. I expected the same to happen to you, so I promised that all your frustrations would be over in three months. I never bargained for your enthusiasm to remain”.

Since I had no role to play now and had implemented many new things, I decided it was time to seek better opportunities elsewhere where I could experiment with my newly gained knowledge.

Seeking New Opportunities

I had applied to a few other places and was selected, but I was still unhappy with the emoluments package. Nothing could match the salary and incentives at the Tyre Corporation despite my new position being at a much higher level. However, the Co-operative Management Services Centre (CMSC), later renamed the Sri Lanka Institute of Co-operative Management (SLICM), offered me the post of General Manager.

Unfortunately, I was informed by the Tyre Corporation that I have to complete the three-year obligatory period because of my training in Japan and that I cannot resign now. I had to decline the lucrative CMSC offer.

The Tyre Corporation was finding it difficult to find a replacement for the post of Finance Manager despite repeated advertisements. Even the previous Finance Manager was partly qualified. I, as the Industrial Engineer, was the only fully qualified Accountant. However, I had not worked a single day as an accountant.

I was very close to the Finance and Accountancy Division staff because my work involved a lot of information from Accounts for my performance analysis. When the advertisement for a Finance Manager (Head of Finance) appeared once more, the staff of the Accounting Division wanted me to apply, assuring me of their fullest support.

They probably went on the premise that the known devil is better than the unknown. I applied, and the Board of Directors interviewed me and asked me only one question: “Are you sure you want this post?” I said yes, and they all said, “Then the post is yours”. Nothing happens in Corporations until the minutes are confirmed at the next Board meeting.

While waiting for the next Board meeting, I heard that the CMSC vacancy was still unfilled. It has been six months since my interview there. I also heard that the Minister responsible for CMSC was in a dilemma because the two internal candidates for the post were from families known to the him, and he did not want to displease the one who would not be selected.

At the same time, my sister, who was Senior Assistant Secretary (Legal) to the Ministry of Justice, took me to meet Mr. S B Herath, the Minister of Food and Co-operatives. Immediately, he ordered CMSC to pay my bond, which was down to half its value by then and bonded me for two years at CMSC instead. He said, “This is only an intra-Government bookkeeping transaction”, so it’s not an issue. The Minister’s dilemma was sorted. An outsider was the better choice. He was probably displeased both internal candidates.

The day before the next Board meeting of the Tyre Corporation, the General Manager asked me to meet him and announced the contents of the letter he had received from the Ministry of Co-operatives. I confirmed my decision to take up the appointment at CMSC. When he got to know of my decision, the Chairman of the Tyre Corporation, Mr Justin Dias, tried to persuade me to remain, but I declined.

Later that evening, my uncle, Mr Sam Wijesinha, a former Secretary General of Parliament and later the Ombudsman, visited me, claiming that Mr Justin Dias had said I was making a terrible mistake. I explained that I knew the new place well because of their pioneering studies in improving co-operative societies with Swedish experts.

My uncle finally accepted my reasoning. My father’s approach was different. He said that even if it is a terrible place, you should take it if you have the courage and ability to turn it around. CMSC paid the bond, and I left the Tyre Corporation.

Moving to the CMSC

The CMSC was set up to provide advice, consultancy services and training for all types of Co-operative Societies. It was also an advisory body that advised the Minister if needed. During the closed economy, it conducted many useful projects such as queue reduction, form design, system design, and other work for the co-operative sector. The consultants were from Agriculture, Industry, Industrial Engineering, and Marketing. This is why the board preferred a multidisciplinary person to head the organization, and I fitted the bill. In addition to the consultants, there was the Administration Division, Documentation division and the support staff.

The previous incumbent of my post was Mr Olcott Gunasekera, who was the Chairman and General Manager. He had retired as the Commissioner of Co-operative Development and then taken the post at CMSC. Subsequently, he resigned from CMSC. When I arrived, the Chairman was Mr P K Dissanayake, who was still the Commissioner of Co-operative Development as well.

On my first day, I understood the culture of the new place. Being taken around, I was introduced to the staff and the building. We were on two floors of the MARKFED building in Grandpass. On my rounds, I noticed that one room shared by two consultants had no window curtains, but all other rooms had. Upon inquiry, I was informed that the two consultants had divergent views about the curtain. One wanted the curtains fully open, while the other wanted them fully closed. One morning, they discovered that the curtains had mysteriously vanished overnight. They were never replaced.

I did not see much enthusiasm at the staff meeting; most were with dull faces. Perhaps they disliked being bossed by a 33 year old General Manager. There was no vibrancy. The issues brought up were mostly petty issues. The next day, one consultant walked into my office with his cup of tea and blamed the administrative officer for the tea’s poor quality and lack of cleanliness. It was shocking. I had hoped they would be ready with plans to revive the co-operative sector rather than surface petty issues.

I realized that a complete overhaul of the culture was necessary. Most staff members were late to the office, and my first task was to issue a circular about being punctual and that there would be no grace period. Suddenly, all support staff, led by an “unofficial leader”, barged into my office about the circular. They had done their homework and found that many government organizations had a grace period except Tyre Corporation.

I stuck to my decision, and people got the message that I meant business. I transformed the sleepy office towards a more vibrant environment by organizing several training seminars for co-operative society staff. The sleepy office sprang to life, with even the idling drivers helping to fold and post the circulars. The place was beginning to change gradually. The older consultants gradually left with new opportunities brought about by the newly opening economy. I was sorry to lose the good experience, though.

More about CMSC in the next episode.

Sunil G Wijesinha

(Consultant on Productivity and Japanese Management Techniques

Retired Chairman/Director of several Listed and Unlisted companies.

Awardee of the APO Regional Award for promoting Productivity in the Asia and Pacific Region

Recipient of the “Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Rays” from the Government of Japan.

He can be contacted through email at bizex.seminarsandconsulting@gmail.com)

Features

Four post-election months as Chairman SLBC and D-G Broadcasting

I was Chairman of the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation and Director-General of Broadcasting only for a period of a little over four months, before I was reassigned. Therefore, a lengthy account of my stewardship in this post would not be necessary. I would however, like to briefly touch upon some salient issues. Firstly, on the management side, I found the organization to lack sufficient vigour. There had developed a looseness dangerously bordering on the careless.

For instance, a Sinhala news reader, who had to do the 6.30 a.m. news bulletin came late by about ten minutes, delaying the station’s opening, in spite of the fact that a car was sent to her residence to pick her up. She had to be sent on compulsory leave pending an inquiry. A large number of employees had got into the habit of aimlessly walking the corridors. That had to be stopped. There were employees playing carom in the canteen, during office hours. The carom boards had to be taken into custody and released only during the lunch hour and after 5 p.m. Stern action was promised against anyone smelling of liquor.

‘The Directors of the divisions were enjoined to have a regular monthly meeting with their staff and the minutes of the meetings sent up to me. I met the Directors once a fortnight. I met the Trade Unions representing all parties and groups regularly. Through these meetings we were able to identify a long checklist of items that needed to be worked on and followed up. The list was then prioritized and specific time periods set for completion of action.

In some instances we later found, that implementation was on schedule, but the quality of the implementation poor. Quality checks were then installed. For some reason, the annual administration report of the Corporation had not been published for a number of years. Therefore, the reports and accounts had not been laid before Parliament. The rectification of this situation was begun. All in all, the entire administration and management of the institution had to be toned up and a degree of rigour injected into the system. This process was set in motion.

On the programme and quality side too, a great deal of collaborative effort had to be put in. Here, unfortunately, we did not have a free hand. Politics came into contention. During the period of the previous government some radio artistes, especially singers had been sidelined allegedly on political grounds, Now with a five-sixths majority in Parliament the rulers wanted to make up for lost time, and virtually demanded five-sixths of programs. The genre of many of them was Sinhala pop, and although I resisted consistently and continuously creating a serious imbalance in the Sinhala music programs, this happened. This initial surge could not be stopped, although towards my last month in office things were coming more into balance.

Amongst the varied programme activities, I was particularly interested in a program initiated by Mr. C. de S. Kulatillake on regional customs, dialects, and language peculiarities, including the Veddah language. We did not have television at this time and there was the danger, that with increased urbanization and migration, some of these linguistic and cultural aspects would be lost forever. I therefore, heavily backed Mr. Kulatilleke’s research and recordings and found ways and means of finding extra funds to sustain his program.

Practical Problems

In an era of non-existent T.V., radio in Sri Lanka had a powerful countrwide reach. Therefore, it naturally attracted the attention of politicians. This was not a healthy situation. Each one vied for more airtime. Each one kept tabs on the news bulletins and was disappointed and angry that their rivals and competitors appeared to get greater exposure. They all felt they were doing great things, but the SLBC only gave publicity to their rivals. This was a serious problem. It tended to disturb the balance of programming and the fair presentation of news.

On the other hand, it was also personally galling. Politicians, including Ministers, telephoned me with a degree of irritation and anger. Some of them accused my staff of partisanship and insisted on giving details of producer X’s close connections with Minister Y, leading to Minister Y getting undue and disproportionate publicity. Others, mercifully just a very few, accused me of trying to bring the government into disrepute. Apparently, according to this thinking the reputation of the government would depend to a large extent on maximizing the sound of their voices on radio.

To add to those woes was Mr. Premadasa, Minister of Local Government Housing and Construction and No. 2 in the UNP. He was obsessed with publicity to the point where all of us including the JSS felt that it was counter productive. He was happiest when arrangements were made for the country to hear his voice in abundance. None of us had a choice in this matter. But I got the flak, including some abusive phone calls, inquiring whether I was stooging Mr. Premadasa! Such are the difficulties of public servants who find themselves in the middle of political dog-fights.

To restore a degree of balance and equilibrium was exceedingly difficult, and it is to the credit of many in the Corporation, that as professional broadcasters, they resisted as far as possible irrespective of their party affiliations. Such resistance had my full encouragement and backing. The Corporation was not the United National Party Broadcasting Corporation or the Sri Lanka Freedom Party Broadcasting Corporation. It was the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation set up by Parliamentary Statute. Therefore, as best as possible, Sri Lanka had to be served.

As Chairman of the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation, I was also Ex-officio a member of the Board of Directors of the State Film Corporation. This was for me, a fascinating field and during my brief tenure there, I tried to bring whatever skills and experience I had, to the better management of the Corporation, as well as encouraging the beginning of a serious dialogue and reflection on policy.

The Artistic Temperament

Besides politics, the other central issue in the internal dynamics of the Corporation was the one of managing the artistic temperament. Artistes were sensitive people. Some of them were very talented. The problem was that the combination of these two qualities also made them very opinionated and often temperamental. Disputes among them were many. Some of them belonged to different schools of music, and had strong views about those of other schools. Some of them thought that they were trained in better musical academies than others. Some thought they had more modern views, which had to be given greater respect and weight.

Underlying these varied views was also the pervasive pressure of commercial competition. An Artiste’s standing in the Corporation was convertible to cash by way of a larger number of invitations to private shows, prospective work with recording companies, and other benefits. Given all these circumstances, an important preoccupation was the settling of squabbles among them, squabbles which threatened the smooth programming that was necessary in order to sustain a large variety of music programs, nvolving substantial broadcast time. I was to encounter later, similar problems with artists and artistes when I became Secretary to the Ministry of Education and Higher Education.

Within a day or two of our arrival in Sri Lanka (from a conference in Belgrade), I received a telephone call from Mr. S.B. Herat, Minister of Food and Cooperatives. He asked me to come and see him. I had neither known nor met Mr. Herat before. But I knew him by sight. When I saw him at his Campbell Place residence, where he stayed with his brother, after asking a few questions, he invited me to become the Secretary to his Ministry.

Mr. K.B. Dissanayke of whom I had written about in a previous chapter, was retiring from service. I inquired from Mr. Herat as to whether my present minister Mr. D.B. Wijetunge was aware that he was going to make this offer to me. He said “No”, but he would be speaking to him. I told him I was sorry, but if my present minister had not been informed, it was not possible for me to continue with this conversation.

This was the tradition we were brought up in. One did not discuss a matter like this behind the back of one’s minister. In fact, I remember the instance in the 1960’s when Mr. D.G. Dayaratne, a senior civil servant who was then functioning as the Port Commissioner when called by the Prime Minister Mrs. Bandaranaike and offered the post of Secretary to the Cabinet declined to discuss the issue, because she had not informed his Minister Mr. Michael Siriwardena. Mr. Dayaratne was later appointed, after the formalities had been concluded.

In my case, Mr. Herat was apologetic and said he would not discuss the matter further, but only wished to know whether I would serve if there was general agreement. I said, “Yes” and that this was based on a principle I followed, of taking up whatever assignment the government of the day wished me to undertake. Mr. Herat appreciated this, and we parted. As I was leaving he said “Please don’t mention this conversation to anybody. I will be clearing matters with your minister and the Prime Minister.” (Mr. Jayewardene was not President yet.)

I promised not to. Matters rested at this for two days. On the morning of the third day which was a holiday, where I had decided to go to the (radio) station later than usual, the telephone at home rang at about 9.30 a.m. The Minister of Lands and Irrigation Mr. Gamini Dissanayake was on the line. He said “Dharmasiri, what are you wasting your time at SLBC for? We are forming a new Ministry of Mahaweli Development. Join me and become its secretary.”

I was now in a serious quandary. I couldn’t tell him that the Food Minister had already spoken to me. I had promised to keep that conversation secret. I therefore rather lamely told Mr. Dissanayake that I knew nothing about irrigation systems or river diversions, and that it was best for him to look for someone with some experience in that area. I suggested Mr. Sivaganam, who was his Secretary in the Ministry of Lands. But Mr. Dissanayake was not to be so easily diverted.

He merely said, “No, you will pick it up in three months. It’s going to be an enormous challenge and a great creative endeavour. Please come. I will speak to the prime minister.” I reminded him that he should speak to my minister first. He promised to do so. To my relief, he did not request me to keep this conversation confidential. I therefore, rang Mr. Herat and was fortunate to find him at home. I requested an immediate appointment. I said that the matter was urgent. He asked me to come.

When I told him what happened, he was visibly upset. He thought that Mr. Dissanayake knew that he was interested in getting me. I told Mr. Herat that the last thing I wanted was to be in the middle of a tug of war between two ministers and to please understand that the present situation was none of my seeking. He was very understanding. He agreed that I should not be misunderstood by anyone.

Mr. Herat told me later that the matter was finally resolved in Cabinet. Both Ministers had argued for me. What had finally clinched the issue had been my previous experience as deputy food commissioner. The government was about to launch a major food policy reform, and they finally concluded that my presence in the food ministry was more important at the time.

Thus it was, that one afternoon, when I had just finished seeing off the French Cultural Attache (at SLBC), who had come to present some recordings of French music, an envelope bearing the seal of President’s House was hand delivered to me. It contained a letter from the Secretary to the President intimating to me that the President was pleased to appoint me as Secretary to the Ministry of Food and Co-operatives “with immediate effect.”

One could not however, abandon responsibilities involved in the only national broadcasting facility “with immediate effect.” What I did “with immediate effect” was to call a series of emergency meetings with all the relevant parties including Heads of Divisions, Trade Unions, and other important persons. The news of my imminent departure spread rapidly, and large numbers of employees sought to see me to express their shock and regret.

Inbetween meetings, I had to find the time to speak to them, however briefly. I had enjoyed good relations with everyone and I felt somewhat sad at the prospect of this sudden departure. I had to dissuade employees and trade unions going in delegation to see the Minister to protest at my going. Amongst the unions, one of the most affected seemed to be the JSS, the same union that protested at my appointment. Now they wanted to protest at my departure. This too, I successfully stopped.

The SLFP Union was extremely unhappy. They had felt secure because of my presence. Now they felt quite insecure. They did not know what type of person would succeed me. My Directors of Divisions were very upset. One of the problems was that to everyone this was a sudden blow. They did not possess my knowledge of the background to all this and I was of course sworn to secrecy.

My meetings went on till near midnight. I myself had not anticipated that my new appointment would come so fast. Therefore, there was much to discuss and decide on, particularly fairly urgent and important matters that would come up during the following few weeks. Then there were important matters to be pursued, both of a bilateral and international nature, consequent to the Non-Aligned Broadcasting conference. I had virtually just come back from that meeting. Responsibilities for follow up action had to be allocated. It turned out to be an exhausting day, and finally when I left the station for the last time another day had dawned.

(Excerpted from In Pursuit of Governance, autobiography of MDD Peiris)

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoRuGoesWild: Taking science into the wild — and into the hearts of Sri Lankans

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoOrders under the provisions of the Prevention of Corruptions Act No. 9 of 2023 for concurrence of parliament

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoNew species of Bronzeback snake, discovered in Sri Lanka

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoProf. Rambukwella passes away

-

Business18 hours ago

Business18 hours agoPick My Pet wins Best Pet Boarding and Grooming Facilitator award

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoPhoto of Sacred tooth relic: CID launches probe

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoSri Lanka’s Foreign Policy amid Geopolitical Transformations: 1990-2024 – Part IX

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoSri Lanka’s Foreign Policy amid Geopolitical Transformations: 1990-2024 – Part VIII