Features

The state of the art: Our cinema

By Uditha Devapriya

(With input from Dhananjaya Samarakoon)

In 1965 the Sri Lankan government published the findings of a Commission of Inquiry into the Film Industry. Filled with proposals and representations from prominent players in the Ceylonese cinema, the Commission made several recommendations. The most important of these was the establishment of a National Film Corporation. Though this would not come to pass until six years later, with the election of a socialist regime committed to a level playing field in the industry, the need for such an institution was frequently underscored.

Among those who made representations to the Commission was Ceylon Theatres. Admitting to the problems of the local cinema, the organisation contended that whether financed by the State or by private players, the film producer “cannot escape the limitations imposed by his audience.” Distinguishing between the cinema and the other arts, it added that while painters, playwrights, novelists, and sculptors could create without paying much regard for the reactions of the masses, the producer remained “the slave of his audience.”

Perhaps the most important point the Commission made was the link between the fortunes of the cinema and the country’s economic problems. Advocating greater intervention in the sector, the centre-left administration which took office in 1970 recognised the problems of allowing a few private players “to virtually control the local film industry.” To that end the new government sought to reduce the influence of monopolistic elements in the market, by regulating the production, distribution, and exhibition of films. Seeking superior production values and greater local output, it tried to give the cinema a new lease of life.

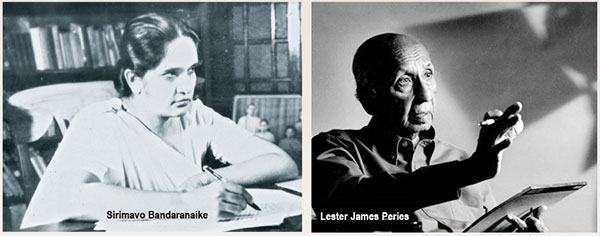

In 1977 the controls enforced by the Sirimavo Bandaranaike administration were loosened. The most immediate result of the new policy was, on the one hand, “ever increasing access to American and Hong Kong productions” and, on the other, the removal of “impediments for newcomers to enter the field.” In other words, from a level playing field, the industry transformed into a business venture. The introduction of television had a considerable say in the reduction of audience numbers that followed, though commentators are divided on the extent to which it led to a fall in cinema hall attendance.

Any examination of the problems and dilemmas of the Sri Lankan cinema must consider these historical developments and shifts. Rather belatedly recognising what should have been acknowledged a long time ago, the Sri Lankan State officially categorised the cinema as an industry late last year. Though this comes too little, too late, it nevertheless behoves us to consider and reflect upon the issues facing the field now, from both administrative and creative standpoints. As always, of course, the link between these issues and the country’s economic problems remains relevant, as much as it did in 1965.

Glancing through the history of the Sri Lankan cinema, from its inception in 1947, we note that the deterioration of creative standards has been rather sharp and dismal. What’s ironic is that despite such a descent, there’s no end to the courses being offered on filmmaking, acting, scriptwriting, and cinematography in the country today. We can conclude that the main contradiction here lies between an ever-fertile reserve of talent and a woeful lack of opportunity for such talent. In other words, we have enough and more talented people. But they lack the money, agency, and access to make full use of their talent.

Part of the reason, which hardly, if at all, gets mentioned by the local commentariat on the cinema, is the absence of an industrial base in the sector. It comes to no surprise that the peak of the Sri Lankan cinema should have been the 1960s and 1970s: these were years in which a flourishing artistic renaissance coincided a not insignificant industrial presence in the film sector. While State intervention became more pronounced under the United Front administration, the existence of a thriving commercial base in the industry ensured a steady stream of not just mainstream, but also artistic productions.

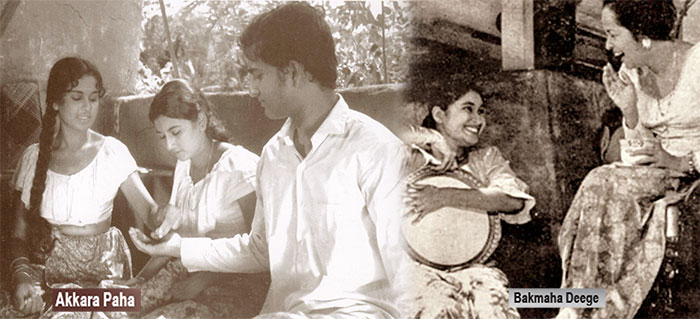

It’s entirely fitting, then, that the cultural revolution heralded by the general election of 1956, which saw a centre-left alliance touting the values of local art forms come to power, should face its peak in these two decades. It’s also fitting that the undisputed doyen of the Sri Lankan cinema, Lester James Peries, should not just make two masterpieces in a row – the highly literate Gamperaliya (1964) and the highly experimental Delovak Athara (1966) – but then follow them up with three further masterpieces, all done for a commercial player, Ceylon Theatres – Golu Hadawatha (1968), Akkara Paha (1969), and Nidhanaya (1970) – in this period. These were years of cultural experimentation, experimentation that benefitted from cultural sectors, especially film, being linked to an industrial framework.

Conversely, the deterioration of the cinema can be traceable to the deterioration of that industrial framework in the country. On the advice of the World Bank, Shiran Ilanperuma writes, the country’s first government “recklessly squandered foreign-currency reserves while avoiding major industrial investment.” Ilanperuma writes that by the 1960s, terms of trade had begun to shift irrevocably, “as the export of primary products and raw materials could not sustain the country’s consumption of imported manufactures.” This had a not insignificant impact on the cinema: by the late 1960s, it was becoming clear that unless the State stepped in, the Ceylonese cinema, for long dependent on an oligopoly of production companies, would collapse. This issue was what the National Film Corporation attempted to address upon its establishment in 1971, as it did over the next few years.

The implementation of swabasha, despite its obvious limitations, also had an impact on the trajectory of the cinema after the 1950s. Though reviled by the English-speaking elite, the empowerment of a Sinhalese-speaking middle-class gave rise to a bilingual intelligentsia, in turn paving the way for a bilingual cultural community. It was from this community that the likes of Dayananda Gunawardena, who gave us the finest adaptation of a French play ever turned into a Sinhalese film, Bakmaha Deege, hailed. While the deterioration of creative and intellectual standards within the population should be admitted, there is no doubt that at its heyday, the Sri Lankan cinema benefitted from a flourishing middle-class.

Today, unfortunately, despite the existence of an upward aspiring and largely Sinhalese middle bourgeoisie, prospects no longer seem good for the local cinema. In any country it is the middle-classes that produce, and reproduce, its cultural elites. In Sri Lanka, though, this community has, however one looks at it, regressed on so many levels, owing mainly to a declining economic situation. We can note the decline of standards in film and television production today, not so much in acting as in scriptwriting and camerawork. We can also note a despairing lack of imagination in films and TV serials: from predictable storylines to endless dialogues, we have come down dismally on so many fronts.

I think the problem has to do with the fact that we no longer explore new themes and issues through the cinema. If we do, we invariably create trends that are imitated and reproduced by a hundred or so other filmmakers and scriptwriters. Ho Gana Pokuna was a brilliant and a highly exceptional film, but it set a precedent for stories about impoverished village schools and idealistic teachers that continue to be filmed, even now. Aloko Udapadi sensationalised audiences and critics, but since its release five years ago we have been making million-rupee budget historical epics which look and feel despairingly predictable.

To be sure, these are hardly any problems specific to only the cinema. When was the last time a cover song didn’t make the rounds online, giving a temporary spotlight to the cover artist while popularising the original tune? When did a mainstream TV series, of which seem to be inundated with these days, not try to cut costs by way of static camera frames and endless expository dialogues? Art exhibitions, especially in Colombo, seem limited to an intellectual upper crust who can afford rental costs in the city and whose work seems not merely cut off from the world around them, but also downright indifferent to it.

We need to acknowledge that there can be no way out for the cinema here unless our cultural industries are linked to a proper industrial framework. In the 1960s, the last peak decade of the three big production companies, Sri Lanka faced an acute terms of trade and structural crisis that the State shielded the cinema from by establishing a Film Corporation and setting high artistic and administrative standards. This did not, to be sure, always work out well, but it did keep the cinema at bay during those difficult days of the 1970s. One can hardly be prudish about the liberalisation of the industry after 1977, but the fact is that the sluggish growth, and then decline, of the cinema remains very much linked to the economic and structural impasses we have been stumbling into since then.

The truth of the matter is that without a proper industrial policy and industrial base, no country’s cinema can be sustained for long. Whether from a creative or an administrative standpoint, the Sri Lankan cinema deserves much more than what it has been subjected to. But where are the policymakers and experts who can prescribe radical solutions, who can recommend an industrialisation plan that can help our cinema take off? In the US, in China, and in India, these problems have been, and are being, combated. In Sri Lanka this does not appear to be the case. That is to be regretted, deeply and sincerely.

(Uditha Devapriya can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com, while Dhananjaya Samarakoon can be reached at dhananjayasmrk@gmail.com)

Features

Cyclones, greed and philosophy for a new world order

Further to my earlier letter titled, “Psychology of Greed and Philosophy for a New World Order” (The Island 26.11.2025) it may not be far-fetched to say that the cause of the devastating cyclones that hit Sri Lanka and Indonesia last week could be traced back to human greed. Cyclones of this magnitude are said to be unusual in the equatorial region but, according to experts, the raised sea surface temperatures created the conditions for their occurrence. This is directly due to global warming which is caused by excessive emission of Greenhouse gases due to burning of fossil fuels and other activities. These activities cannot be brought under control as the rich, greedy Western powers do not want to abide by the terms and conditions agreed upon at the Paris Agreement of 2015, as was seen at the COP30 meeting in Brazil recently. Is there hope for third world countries? This is why the Global South must develop a New World Order. For this purpose, the proposed contentment/sufficiency philosophy based on morals like dhana, seela, bhavana, may provide the necessary foundation.

Further, such a philosophy need not be parochial and isolationist. It may not be necessary to adopt systems that existed in the past that suited the times but develop a system that would be practical and also pragmatic in the context of the modern world.

It must be reiterated that without controlling the force of collective greed the present destructive socioeconomic system cannot be changed. Hence the need for a philosophy that incorporates the means of controlling greed. Dhana, seela, bhavana may suit Sri Lanka and most of the East which, as mentioned in my earlier letter, share a similar philosophical heritage. The rest of the world also may have to adopt a contentment / sufficiency philosophy with strong and effective tenets that suit their culture, to bring under control the evil of greed. If not, there is no hope for the existence of the world. Global warming will destroy it with cyclones, forest fires, droughts, floods, crop failure and famine.

Leading economists had commented on the damaging effect of greed on the economy while philosophers, ancient as well as modern, had spoken about its degenerating influence on the inborn human morals. Ancient philosophers like Plato, Aristotle, and Epicurus all spoke about greed, viewing it as a destructive force that hindered a good life. They believed greed was rooted in personal immorality and prevented individuals from achieving true happiness by focusing on endless material accumulation rather than the limited wealth needed for natural needs.

Jeffry Sachs argues that greed is a destructive force that undermines social and environmental well-being, citing it as a major driver of climate change and economic inequality, referencing the ideas of Adam Smith, John Maynard Keynes, etc. Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel Laureate economist, has criticised neoliberal ideology in similar terms.

In my earlier letter, I have discussed how contentment / sufficiency philosophy could effectively transform the socioeconomic system to one that prioritises collective well-being and sufficiency over rampant consumerism and greed, potentially leading to more sustainable economic models.

Obviously, these changes cannot be brought about without a change of attitude, morals and commitment of the rulers and the government. This cannot be achieved without a mass movement; people must realise the need for change. Such a movement would need leadership. In this regard a critical responsibility lies with the educated middle class. It is they who must give leadership to the movement that would have the goal of getting rid of the evil of excessive greed. It is they who must educate the entire nation about the need for these changes.

The middle class would be the vanguard of change. It is the middle class that has the capacity to bring about change. It is the middle class that perform as a vibrant component of the society for political stability. It is the group which supplies political philosophy, ideology, movements, guidance and leaders for the rest of the society. The poor, who are the majority, need the political wisdom and leadership of the middle class.

Further, the middle class is the font of culture, creativity, literature, art and music. Thinkers, writers, artistes, musicians are fostered by the middle class. Cultural activity of the middle class could pervade down to the poor groups and have an effect on their cultural development as well. Similarly, education of a country depends on how educated the middle class is. It is the responsibility of the middle class to provide education to the poor people.

Most importantly, the morals of a society are imbued in the middle class and it is they who foster them. As morals are crucial in the battle against greed, the middle class assume greater credentials to spearhead the movement against greed and bring in sustainable development and growth. Contentment sufficiency philosophy, based on morals, would form the strong foundation necessary for achieving the goal of a new world order. Thus, it is seen that the middle class is eminently suitable to be the vehicle that could adopt and disseminate a contentment/ sufficiency philosophy and lead the movement against the evil neo-liberal system that is destroying the world.

The Global South, which comprises the majority of the world’s poor, may have to realise, before it is too late, that it is they who are the most vulnerable to climate change though they may not be the greatest offenders who cause it. Yet, if they are to survive, they must get together and help each other to achieve self-sufficiency in the essential needs, like food, energy and medicine. Trade must not be via exploitative and weaponised currency but by means of a barter system, based on purchase power parity (PPP). The union of these countries could be an expansion of organisations,like BRICS, ASEAN, SCO, AU, etc., which already have the trade and financial arrangements though in a rudimentary state but with great potential, if only they could sort out their bilateral issues and work towards a Global South which is neither rich nor poor but sufficient, contented and safe, a lesson to the Global North. China, India and South Africa must play the lead role in this venture. They would need the support of a strong philosophy that has the capacity to fight the evil of greed, for they cannot achieve these goals if fettered by greed. The proposed contentment / sufficient philosophy would form a strong philosophical foundation for the Global South, to unite, fight greed and develop a new world order which, above all, will make it safe for life.

by Prof. N. A. de S. Amaratunga

PHD, DSc, DLITT

Features

SINHARAJA: The Living Cathedral of Sri Lanka’s Rainforest Heritage

When Senior biodiversity scientist Vimukthi Weeratunga speaks of Sinharaja, his voice carries the weight of four decades spent beneath its dripping emerald canopy. To him, Sri Lanka’s last great rainforest is not merely a protected area—it is “a cathedral of life,” a sanctuary where evolution whispers through every leaf, stream and shadow.

“Sinharaja is the largest and most precious tropical rainforest we have,” Weeratunga said.

“Sixty to seventy percent of the plants and animals found here exist nowhere else on Earth. This forest is the heart of endemic biodiversity in Sri Lanka.”

A Magnet for the World’s Naturalists

Sinharaja’s allure lies not in charismatic megafauna but in the world of the small and extraordinary—tiny, jewel-toned frogs; iridescent butterflies; shy serpents; and canopy birds whose songs drift like threads of silver through the mist.

“You must walk slowly in Sinharaja,” Weeratunga smiled.

“Its beauty reveals itself only to those who are patient and observant.”

For global travellers fascinated by natural history, Sinharaja remains a top draw. Nearly 90% of nature-focused visitors to Sri Lanka place Sinharaja at the top of their itinerary, generating a deep economic pulse for surrounding communities.

A Forest Etched in History

Centuries before conservationists championed its cause, Sinharaja captured the imagination of explorers and scholars. British and Dutch botanists, venturing into the island’s interior from the 17th century onward, mapped streams, documented rare orchids, and penned some of the earliest scientific records of Sri Lanka’s natural heritage.

These chronicles now form the backbone of our understanding of the island’s unique ecology.

The Great Forest War: Saving Sinharaja

But Sinharaja nearly vanished.

In the 1970s, the government—guided by a timber-driven development mindset—greenlit a Canadian-assisted logging project. Forests around Sinharaja fell first; then, the chainsaws approached the ancient core.

“There was very little scientific data to counter the felling,” Weeratunga recalled.

- Poppie’s shrub frog

- Endemic Scimitar babblers

- Blue Magpie

“But people knew instinctively this was a national treasure.”

The public responded with one of the greatest environmental uprisings in Sri Lankan history. Conservation icons Thilo Hoffmann and Neluwe Gunananda Thera led a national movement. After seven tense years, the new government of 1977 halted the project.

What followed was a scientific renaissance. Leading researchers—including Prof. Savithri Gunathilake and Prof. Nimal Gunathilaka, Prof. Sarath Kottagama, and others—descended into the depths of Sinharaja, documenting every possible facet of its biodiversity.

“Those studies paved the way for Sinharaja to become Sri Lanka’s very first natural World Heritage Site,” Weeratunga noted proudly.

- Vimukthi

- Nadika

- Janaka

A Book Woven From 30 Years of Field Wisdom

For Weeratunga, Sinharaja is more than academic terrain—it is home. Since joining the Forest Department in 1985 as a young researcher, he has trekked, photographed, documented and celebrated its secrets.

Now, decades later, he joins Dr. Thilak Jayaratne, the late Dr. Janaka Gallangoda, and Nadika Hapuarachchi in producing, what he calls, the most comprehensive book ever written on Sinharaja.

“This will be the first major publication on Sinharaja since the early 1980s,” he said.

“It covers ecology, history, flora, fauna—and includes rare photographs taken over nearly 30 years.”

Some images were captured after weeks of waiting. Others after years—like the mysterious mass-flowering episodes where clusters of forest giants bloom in synchrony, or the delicate jewels of the understory: tiny jumping spiders, elusive amphibians, and canopy dwellers glimpsed only once in a lifetime.

The book even includes underwater photography from Sinharaja’s crystal-clear streams—worlds unseen by most visitors.

A Tribute to a Departed Friend

Halfway through the project, tragedy struck: co-author Dr. Janaka Gallangoda passed away.

“We stopped the project for a while,” Weeratunga said quietly.

“But Dr. Thilak Jayaratne reminded us that Janaka lived for this forest. So we completed the book in his memory. One of our authors now watches over Sinharaja from above.”

An Invitation to the Public

A special exhibition, showcasing highlights from the book, will be held on 13–14 December, 2025, in Colombo.

“We cannot show Sinharaja in one gallery,” he laughed.

“But we can show a single drop of its beauty—enough to spark curiosity.”

A Forest That Must Endure

What makes the book special, he emphasises, is its accessibility.

“We wrote it in simple, clear language—no heavy jargon—so that everyone can understand why Sinharaja is irreplaceable,” Weeratunga said.

“If people know its value, they will protect it.”

To him, Sinharaja is more than a rainforest.

It is Sri Lanka’s living heritage.

A sanctuary of evolution.

A sacred, breathing cathedral that must endure for generations to come.

By Ifham Nizam

Features

How Knuckles was sold out

Leaked RTI Files Reveal Conflicting Approvals, Missing Assessments, and Silent Officials

“This Was Not Mismanagement — It Was a Structured Failure”— CEJ’s Dilena Pathragoda

An investigation, backed by newly released Right to Information (RTI) files, exposes a troubling sequence of events in which multiple state agencies appear to have enabled — or quietly tolerated — unauthorised road construction inside the Knuckles Conservation Forest, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

At the centre of the unfolding scandal is a trail of contradictory letters, unexplained delays, unsigned inspection reports, and sudden reversals by key government offices.

“What these documents show is not confusion or oversight. It is a structured failure,” said Dilena Pathragoda, Executive Director of the Centre for Environmental Justice (CEJ), who has been analysing the leaked records.

“Officials knew the legal requirements. They ignored them. They knew the ecological risks. They dismissed them. The evidence points to a deliberate weakening of safeguards meant to protect one of Sri Lanka’s most fragile ecosystems.”

A Paper Trail of Contradictions

RTI disclosures obtained by activists reveal:

Approvals issued before mandatory field inspections were carried out

Three departments claiming they “did not authorise” the same section of the road

A suspiciously backdated letter clearing a segment already under construction

Internal memos flagging “missing evaluation data” that were never addressed

“No-objection” notes do not hold any legal weight for work inside protected areas, experts say.

One senior officer’s signature appears on two letters with opposing conclusions, sent just three weeks apart — a discrepancy that has raised serious questions within the conservation community.

“This is the kind of documentation that usually surfaces only after damage is done,” Pathragoda said. “It shows a chain of administrative behaviour designed to delay scrutiny until the bulldozers moved in.”

The Silence of the Agencies

Perhaps, more alarming is the behaviour of the regulatory bodies.

Multiple departments — including those legally mandated to halt unauthorised work — acknowledged concerns in internal exchanges but issued no public warnings, took no enforcement action, and allowed machinery to continue operating.

“That silence is the real red flag,” Pathragoda noted.

“Silence is rarely accidental in cases like this. Silence protects someone.”

On the Ground: Damage Already Visible

Independent field teams report:

Fresh erosion scars on steep slopes

Sediment-laden water in downstream streams

Disturbed buffer zones

Workers claiming that they were instructed to “complete the section quickly”

Satellite images from the past two months show accelerated clearing around the contested route.

Environmental experts warn that once the hydrology of the Knuckles slopes is altered, the consequences could be irreversible.

CEJ: “Name Every Official Involved”

CEJ is preparing a formal complaint demanding a multi-agency investigation.

Pathragoda insists that responsibility must be traced along the entire chain — from field officers to approving authorities.

“Every signature, every omission, every backdated approval must be examined,” she said.

“If laws were violated, then prosecutions must follow. Not warnings. Not transfers. Prosecutions.”

A Scandal Still Unfolding

More RTI documents are expected to come out next week, including internal audits and communication logs that could deepen the crisis for several agencies.

As the paper trail widens, one thing is increasingly clear: what happened in Knuckles is not an isolated act — it is an institutional failure, executed quietly, and revealed only because citizens insisted on answers.

by Ifham Nizam

-

News5 days ago

Lunuwila tragedy not caused by those videoing Bell 212: SLAF

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoLevel III landslide early warning continue to be in force in the districts of Kandy, Kegalle, Kurunegala and Matale

-

Latest News6 days ago

Latest News6 days agoLevel III landslide early warnings issued to the districts of Badulla, Kandy, Kegalle, Kurunegala, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoDitwah: An unusual cyclone

-

Latest News7 days ago

Latest News7 days agoUpdated Payment Instructions for Disaster Relief Contributions

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoCPC delegation meets JVP for talks on disaster response

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoLOLC Finance Factoring powers business growth

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoA 6th Year Accolade: The Eternal Opulence of My Fair Lady