Foreign News

Battling a rare brain-eating disease in an Indian state

On the eve of Onam, the most joyous festival in India’s Kerala state, 45-year-old Sobhana lay shivering in the back of an ambulance, drifting into unconsciousness as her family rushed her to a medical college hospital.

Just days earlier, the Dalit (formerly known as untouchables) woman, who earned her living bottling fruit juices in a village in Malappuram district, had complained of nothing more alarming than dizziness and high blood pressure. Doctors prescribed pills and sent her home. But her condition spiralled with terrifying speed: uneasiness gave way to fever, fever to violent shivers, and on 5 September – the main day of the festival – Sobhana was dead.

The culprit was Naegleria fowleri – commonly known as the brain-eating amoeba – an infection usually contracted through the nose in freshwater and so rare that most doctors never encounter a case in their entire careers. “We were powerless to stop it. We learnt about the disease only after Sobhana’s death,” says Ajitha Kathiradath, a cousin of the victim and a prominent social worker.

In Kerala this year, more than 70 people have been diagnosed and 19 have died from the brain-eating amoeba. Patients have ranged from a three-month-old to a 92-year-old man.

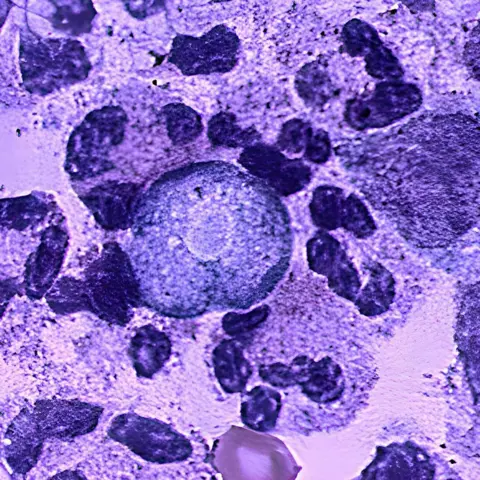

Normally feeding on bacteria in warm freshwater, this single-cell organism causes a near-fatal brain infection, known as primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM). It enters through the nose during swimming and rapidly destroys brain tissue.

Kerala began detecting cases in 2016, just one or two a year, and until recently nearly all were fatal. A new study has found only 488 cases have been reported globally since 1962 – mostly in the US, Pakistan and Australia. And 95% of the victims have died from the disease.

But in Kerala, survival appears to be improving: last year there were 39 cases with a 23% fatality rate and this year, nearly 70 cases have been reported with about 24.5% mortality. Doctors say the rise in numbers reflects better detection, thanks to state-of-the-art labs.

“Cases are rising but deaths are falling. Aggressive testing and early diagnosis have improved survival – a strategy unique to Kerala,” said Aravind Reghukumar, head of infectious diseases at the Medical College and Hospital in Thiruvananthapuram, the state’s capital. Early detection allows customised treatment: a drug cocktail of antimicrobials and steroids targeting the amoeba can save lives.

Scientists have identified around 400 species of free-living amoebae, but only six are known to cause disease in humans – including Naegleria fowleri and Acanthamoeba, both of which can infect the brain. In Kerala, public health laboratories can now detect the five major pathogenic types, officials say.

The southern state’s heavy reliance on groundwater and natural water bodies makes it particularly vulnerable, especially as many ponds and wells are polluted. A small cluster of cases last year, for example, was linked to young men vaping boiled cannabis mixed with pond water – a risky practice that underscores how contaminated water can become a conduit for infection.

Kerala has nearly 5.5 million wells and 55,000 ponds – and millions draw their daily water from wells alone. That sheer ubiquity makes it impossible to treat wells or ponds as simple “risk factors” – they are the backbone of life in the state.

“Some infections have occurred in people bathing in ponds, others from swimming pools, and even through nasal rinsing with water which is a religious ritual. Whether in a polluted pond or a well, the risk is real,” says Anish TS, a leading epidemiologist.

So public health authorities have tried to respond at scale: in a single campaign at the end of August, 2.7 million wells were chlorinated.

Local governments have put up sign boards around ponds warning against bathing or swimming and evoked the Public Health Act to enforce regular chlorination of swimming pools and water tanks. But even with such measures, ponds cannot realistically be chlorinated – fish would die – and policing every village water source in a state of more than 30 million people is unworkable.

Officials now stress awareness over prohibition: households are urged to clean tanks and pools, use clean warm water for nasal ablutions, keep children away from garden sprinklers and avoid unsafe ponds. Swimmers are advised to protect their noses by keeping their heads above water, using nose plugs and avoiding stirring up sediment in stagnant or untreated freshwater.

Yet, striking a balance between educating the public about real risks – of using untreated freshwater – and avoiding fear that could disrupt daily life is challenging. Many say despite guidelines issued for more than a year, enforcement remains patchy.

“This is a difficult problem. In some places [hot springs], signs are posted to warn of the possibility of the amoebae in the water source. This is not practical in most situations since the amoebae can be present in any source of untreated water [lakes, ponds, pools],” Dennis Kyle, a professor of infectious diseases and cellular biology at the University of Georgia, told the BBC.

“In more controlled environments, frequent monitoring for proper chlorination can significantly reduce chances of infection. These include pools, splash pads and other man-made recreational water activities,” he said.

Scientists warn climate change is amplifying the risk: warmer waters, longer summers and rising temperatures create ideal conditions for the amoeba. “Even a 1C rise can trigger its spread in Kerala’s tropical climate and water pollution fuels it further by feeding bacteria the amoeba consumes,” says Prof Anish.

Dr Kyle adds a note of caution, noting that some past cases may simply have gone unrecognised, with the amoeba not identified as the cause.

That uncertainty can make treatment even harder. Current drug cocktails are “sub-optimal,” Dr Kyle explains, adding that in rare survivors, the regimen becomes the standard. “We lack sufficient data to determine if all the drugs are actually helpful or needed.”

Kerala may be catching more patients and saving more lives, but the lesson reaches far beyond its borders. Climate change may be rewriting the map of disease – and even the rarest pathogens may not stay rare for long.

[BBC]

Foreign News

Austria bans headscarves in schools for under-14s

Austria has passed a law banning headscarves in schools for girls under the age of 14.

The conservative-led coalition of three centrist parties, the ÖVP, the SPÖ and the Neos, says the law is a “clear commitment to gender equality”, but critics say it will fuel anti-Muslim feeling in the country and could be unconstitutional.

The measure will apply to girls in both public and private schools.

In 2020, a similar headscarf ban for girls under 10 was struck down by the Constitutional Court, because it specifically targeted Muslims.

The terms of the new law mean girls under 14 will be forbidden from wearing “traditional Muslim” head coverings such as hijabs or burkas.

If a student violates the ban, they must have a series of discussions with school authorities and their legal guardians. If there are repeated violations, the child and youth welfare agency must be notified.

As a last resort, families or guardians could be fined up to €800 (£700).

Members of the government say this is about empowering young girls, arguing it is to protect them “from oppression”.

Speaking ahead of the vote, the parliamentary leader of the liberal Neos party, Yannick Shetty said it was “not a measure against a religion. It is a measure to protect the freedom of girls in this country,” and added that the ban would affect about 12,000 children.

The opposition far-right Freedom Party of Austria, the FPÖ, which voted in favour of the ban, said it did not go far enough.

It described the ban as “a first step”, which should be widened to include all pupils and school staff.

“There needs to be a general ban on headscarves in schools; political Islam has no place here”, the FPÖ’s spokesperson on families Ricarda Berger said.

Sigrid Maurer from the opposition Greens called the new law “clearly unconstitutional”.

The official Islamic Community in Austria, the IGGÖ, said the ban violated fundamental rights and would split society.

In a statement on its website, it said “instead of empowering children, they will be stigmatised and marginalised.”

The IGGÖ said it would review “the constitutionality of the law and take all necessary steps.”

“The Constitutional Court already ruled unequivocally in 2020 that such a ban is unconstitutional, as it specifically targets a religious minority and violates the principle of equality,” the IGGÖ said.

The government says it has tried to avoid that.

“Will it pass muster with the Constitutional Court? I don’t know. We have done our best,” Shetty said.

An awareness-raising trial period will start in February 2026, with the ban fully going into force next September – the beginning of the new school year.

[BBC]

Foreign News

More than 30 dead after Myanmar military air strike hits hospital

At least 34 people have died and dozens more are injured after air strikes from Myanmar’s military hit a hospital in the country’s west on Wednesday night, according to ground sources.

The hospital is located in Mrauk-U town in Rakhine state, an area controlled by the Arakan Army – one of the strongest ethnic armies fighting the country’s military regime.

Thousands have died and millions have been displaced since the military seized power in a coup in 2021 and triggered a civil war.

In recent months, the military has intensified air strikes to take back territory from ethnic armies. It has also developed paragliders to drop bombs on its enemies.

The Myanmar military has not commented on the strikes, which come as the country prepares to vote later this month in its first election since the coup.

However, pro-military accounts on Telegram claim the strikes this week were not aimed at civilians.

Khaing Thukha, a spokesperson for the Arakan Army, told the BBC that most of the casualties were patients at the hospital.

“This is the latest vicious attack by the terrorist military targeting civilian places,” he said, adding that the military “must take responsibility” for bombing civilians.

The Arakan Army health department said the strike, which occurred at around 21:00 (14:30 GMT), killed 10 patients on the spot and injured many others.

Photos believed to be from the scene have been circulating on social media showing missing roofs across parts of the building complex, broken hospital beds and debris strewn across the ground.

The junta has been locked in a years-long bloody conflict with ethnic militias, at one point losing control of more than half the country.

But recent influx of technology and equipment from China and Russia seems to have helped it turn the tide. The junta has made significant gains through a campaign of airstrikes and heavy bombardment.

Earlier this year, more than 20 people were killed after an army motorised paraglider dropped two bombs on a crowd protesting at a religious festival.

Civil liberties have also shrunk dramatically under the junta. Tens of thousands of political dissidents have been arrested, rights groups estimate.

Myanmar’s junta has called for a general election on 28 December, touting it as a pathway to political stability.

But critics say the election will be neither free nor fair, but will instead offer the junta a guise of legitimacy. Tom Andrews, the United Nations’ human rights expert on Myanmar, has called it a “sham election”.

In recent weeks the junta has arrested civilians accused of disrupting the vote, including one man who authorities said had sent out anti-election messages on Facebook.

The junta also said on Monday that it was looking for 10 activists involved in an anti-election protest.

Ethnic armies and other opposition groups have pledged to boycott the polls.

At least one election candidate in in central Myanmar’s Magway Region was detained by an anti-junta group, the Associated Press reported.

[BBC]

Features

A wage for housework? India’s sweeping experiment in paying women

In a village in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh, a woman receives a small but steady sum each month – not wages, for she has no formal job, but an unconditional cash transfer from the government.

Premila Bhalavi says the money covers medicines, vegetables and her son’s school fees. The sum, 1,500 rupees ($16: £12), may be small, but its effect – predictable income, a sense of control and a taste of independence – is anything but.

Her story is increasingly common. Across India, 118 million adult women in 12 states now receive unconditional cash transfers from their governments, making India the site of one of the world’s largest and least-studied social-policy experiments.

Long accustomed to subsidising grain, fuel and rural jobs, India has stumbled into something more radical: paying adult women simply because they keep households running, bear the burden of unpaid care and form an electorate too large to ignore.

Eligibility filters vary – age thresholds, income caps and exclusions for families with government employees, taxpayers or owners of cars or large plots of land.

“The unconditional cash transfers signal a significant expansion of Indian states’ welfare regimes in favour of women,” Prabha Kotiswaran, a professor of law and social justice at King’s College London, told the BBC.

The transfers range from 1,000-2,500 rupees ($12-$30) a month – meagre sums, worth roughly 5-12% of household income, but regular. With 300 million women now holding bank accounts, transfers have become administratively simple.

Women typically spend the money on household and family needs – children’s education, groceries, cooking gas, medical and emergency expenses, retiring small debts and occasional personal items like gold or small comforts.

What sets India apart from Mexico, Brazil or Indonesia – countries with large conditional cash-transfer schemes – is the absence of conditions: the money arrives whether or not a child attends school or a household falls below the poverty line.

Goa was the first state to launch an unconditional cash transfer scheme to women in 2013. The phenomenon picked up just before the pandemic in 2020, when north-eastern Assam rolled out a scheme for vulnerable women. Since then these transfers have turned into a political juggernaut.

The recent wave of unconditional cash transfers targets adult women, with some states acknowledging their unpaid domestic and care work. Tamil Nadu frames its payments as a “rights grant” while West Bengal’s scheme similarly recognises women’s unpaid contributions.

In other states, the recognition is implicit: policymakers expect women to use the transfers for household and family welfare, say experts.

This focus on women’s economic role has also shaped politics: in 2021, Tamil actor-turned-politician Kamal Haasan promised “salaries for housewives”. (His fledgling party lost.) By 2024, pledges of women-focused cash transfers helped deliver victories to political parties in Maharashtra, Jharkhand, Odisha, Haryana and Andhra Pradesh.

In the recent elections in Bihar, the political power of cash transfers was on stark display. In the weeks before polling in the country’s poorest state, the government transferred 10,000 rupees ($112; £85) to 7.5 million female bank accounts under a livelihood-generation scheme. Women voted in larger numbers than men, decisively shaping the outcome.

Critics called it blatant vote-buying, but the result was clear: women helped the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led coalition secure a landslide victory. Many believe this cash infusion was a reminder of how financial support can be used as political leverage.

Yet Bihar is only one piece of a much larger picture. Across India, unconditional cash transfers are reaching tens of millions of women on a regular basis.

Maharashtra alone promises benefits for 25 million women; Odisha’s scheme reaches 71% of its female voters.

In some policy circles, the schemes are derided as vote-buying freebies. They also put pressure on state finances: 12 states are set to spend around $18bn on such payouts this fiscal year. A report by think-tank PRS Legislative Research notes that half of these states face revenue deficits – this happens when a state borrows to pay regular expenses without creating assets.

But many argue they also reflect a slow recognition of something India’s feminists have argued for decades: the economic value of unpaid domestic and care work.

Women in India spent nearly five hours a day on such work in 2024 – more than three times the time spent by men, according to the latest Time Use Survey. This lopsided burden helps explain India’s stubbornly low female labour-force participation. The cash transfers, at least, acknowledge the imbalance, experts say.

Do they work?

Evidence is still thin but instructive. A 2025 study in Maharashtra found that 30% of eligible women did not register – sometimes because of documentation problems, sometimes out of a sense of self-sufficiency. But among those who did, nearly all controlled their own bank accounts.

A 2023 survey in West Bengal found that 90% operated their accounts themselves and 86% decided how to spend the money. Most used it for food, education and medical costs; hardly transformative, but the regularity offered security and a sense of agency.

More detailed work by Prof Kotiswaran and colleagues shows mixed outcomes.

In Assam, most women spent the money on essentials; many appreciated the dignity it afforded, but few linked it to recognition of unpaid work, and most would still prefer paid jobs.

In Tamil Nadu, women getting the money spoke of peace of mind, reduced marital conflict and newfound confidence – a rare social dividend. In Karnataka, beneficiaries reported eating better, gaining more say in household decisions and wanting higher payments.

Yet only a sliver understood the scheme as compensation for unpaid care work; messaging had not travelled. Even so, women said the money allowed them to question politicians and manage emergencies. Across studies, the majority of women had full control of the cash.

“The evidence shows that the cash transfers are tremendously useful for women to meet their own immediate needs and those of their households. They also restore dignity to women who are otherwise financially dependent on their husbands for every minor expense,” Prof Kotiswaran says.

Importantly, none of the surveys finds evidence that the money discourages women from seeking paid work or entrench gender roles – the two big feminist fears, according to a report by Prof Kotiswaran along with Gale Andrew and Madhusree Jana.

Nor have they reduced women’s unpaid workload, the researchers find. They do, however, strengthen financial autonomy and modestly strengthen bargaining power. They are neither panacea nor poison: they are useful but limited tools, operating in a patriarchal society where cash alone cannot undo structural inequities.

What next?

The emerging research offers clear hints.

Eligibility rules should be simplified, especially for women doing heavy unpaid care work. Transfers should remain unconditional and independent of marital status.

But messaging should emphasise women’s rights and the value of unpaid work, and financial-literacy efforts must deepen, researchers say. And cash transfers cannot substitute for employment opportunities; many women say what they really want is work that pays and respect that endures.

“If the transfers are coupled with messaging on the recognition of women’s unpaid work, they could potentially disrupt the gendered division of labour when paid employment opportunities become available,” says Prof Kotiswaran.

India’s quiet cash transfers revolution is still in its early chapters. But it already shows that small, regular sums – paid directly to women – can shift power in subtle, significant ways.

Whether this becomes a path to empowerment or merely a new form of political patronage will depend on what India chooses to build around the money.

[BBC]

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoOver 35,000 drug offenders nabbed in 36 days

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoFinally, Mahinda Yapa sets the record straight

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoLOLC Finance Factoring powers business growth

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoCyclone Ditwah leaves Sri Lanka’s biodiversity in ruins: Top scientist warns of unseen ecological disaster

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoCPC delegation meets JVP for talks on disaster response

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoA 6th Year Accolade: The Eternal Opulence of My Fair Lady

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoRising water level in Malwathu Oya triggers alert in Thanthirimale

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoThe Catastrophic Impact of Tropical Cyclone Ditwah on Sri Lanka: