Features

Back in the saddle as Secretary/PM:Ranil-CBK tensions after 2001 election

A day after the December 5, 2001 general election results were out, I got a call from Ranil Wickremesinghe’s private office at Cambridge Terrace. It was Dayaratne, Ranil’s personal secretary, with a message that the ‘boss’ wanted to see me urgently.

Ranil was brief and to the point as usual. He wasted no time on the formalities. He returned my congratulatory handshake with his normal perfunctory acknowledgement. He waved me to a chair.

“Brad,” he said, “I have a problem.”

I thought I would be flippant; after all it was a moment for celebration.

“Not one, I think you have got quite a few.”

“No, but there is a serious one,” said Ranil. “What’s that?”

“I don’t have a secretary.”

I was relieved. All he wanted were a few good names.

“That’s not too difficult, I can suggest a few names,” I ventured. “No, no, I want you.”

That really floored me.

“Me! Do you know how old I am?”” You must be about sixty five.”

“No. I am 71. I don’t think I can last the pace.” “But you are well, aren’t you. You look okay.” He looked so earnest. I played for time.

“I can help you out for about three months and then…

“No. Come for about a year and we’ll see … “

I knew I’d had it. I tried once more to obtain release. on my 72nd birthday dinner at which he was a special invitee, but I don’t think he was listening. Today April 2, 2004, as the country votes again at the general elections that President Chandrika Kumaratunga has called, I would have been with him over two years and three months.

Ranil had won the 2001 December election with a comfortable majority. From the opposition, and with a formidable array of forces against him he had prevailed and brought off a comprehensive victory. The final results showed the following alignment of seats in Parliament:

Party No of Votes Seats

UNP 4,086,026 109

PA 3,330,815 77

JVP 518,774 16

He had focused on a single issue that of bringing peace once more to people and a country devastated by 20 years of war. I felt I could not in good faith turn down his invitation. After all it would only be for a few months during which we, he and I, would find someone else for the job.

I had not thought of re-entering government service ever again. I had officially retired many years ago and was enjoying my life in semi-retirement. I had a sinecure’ in the private sector as chairman of a shipping company (where I was literally all at sea!) and with lots of free time in the late afternoon for seminars and such like. I must have been very regular at these seminars since some observant people apparently gained the impression that I had a permanent job at the International Centre for Ethnic Studies (ICES). I had some time too for golf, whose mysterious ways I now decided to take up for diligent study on a free morning.

There was also another project I had planned to do which had already been long delayed. This was to write a book on the lives of the prime ministers and presidents whom I had worked with. Where would I have time for this if I went back to work as secretary to the prime minister? And this time not even as an advisor which I had been to Premadasa when he was president, but as a full- fledged public official with all the financial and establishment responsibilities that such a position entailed. What would my erstwhile friends say? ‘Never know when to give up’; ‘still after the power and glory’, etc. And the all-knowing media? Wasn’t ‘Uncle Brad’ far too old and so on? To most of these I properly belonged, like others of my age, now `lean and slippered’, to lounging around the house and having a beer with my buddies at sundown at the local pub.

But there was one important matter which, if I could stir myself to help Ranil, would be still worthwhile doing. Perhaps the last hurrah! He was going to stop the war. He had made a promise to do that and I reckoned that he had the guts to keep his word. No one before had succeeded or even gone half-way.

I had seen throughout the years, the pain, the fear and the sense of loss which conflict brought in its wake to ordinary people. I had seen it in Ampara; in the faces of the young men and women captured after the JVP uprising and awaiting an uncertain future; I had been witness to it in 1983 in the heartbreaking refugee camps throughout_the country. I had seen it at the funerals and in the homes of soldiers and friends slain in battles far away.

I found it incomprehensible to see the disbelief on the faces of the young widows as they refused to reconcile themselves to the fact that their husbands are most likely injured or even dead when engaged in war. (I used to ask myself whether they had not known that death or serious injury was part of a soldier’s lot; or had the astrologers prediction and the prayers they daily offered to the gods dulled them into thinking that what to them was ‘impossible’ would not come their way).

I was appalled at the massive destruction of private property and public assets that security ‘operations’ and the bomb attacks of the terrorists in both north and south had caused over the 20 years of war.

Much of the time I had spent in the company of civil society NGO groups was in discussion on the hapless condition, particularly, of women and children whose hopes and expectations had been destroyed by the unending conflict.

Some of the `consultancies’ I had done for the UN system, particularly in the protection of children, had highlighted the dreadful consequences of the war. Perhaps the ‘pluses’ of being able to do something substantial through being at the prime minister’s office, of stopping the daily killing and maiming of both soldiers and civilians, might be time worthwhile spent in this last official chapter of my life.

This would probably compensate for the daily grind of dressing up in the morning, foregoing the long afternoon nap, poring through those bulky files and lengthy minutes, chairing unending meetings and pushing generally indifferent and demotivated staff. Everything would be different now; at Temple Trees and even in the prime minister’s office, from what I had known several years ago.

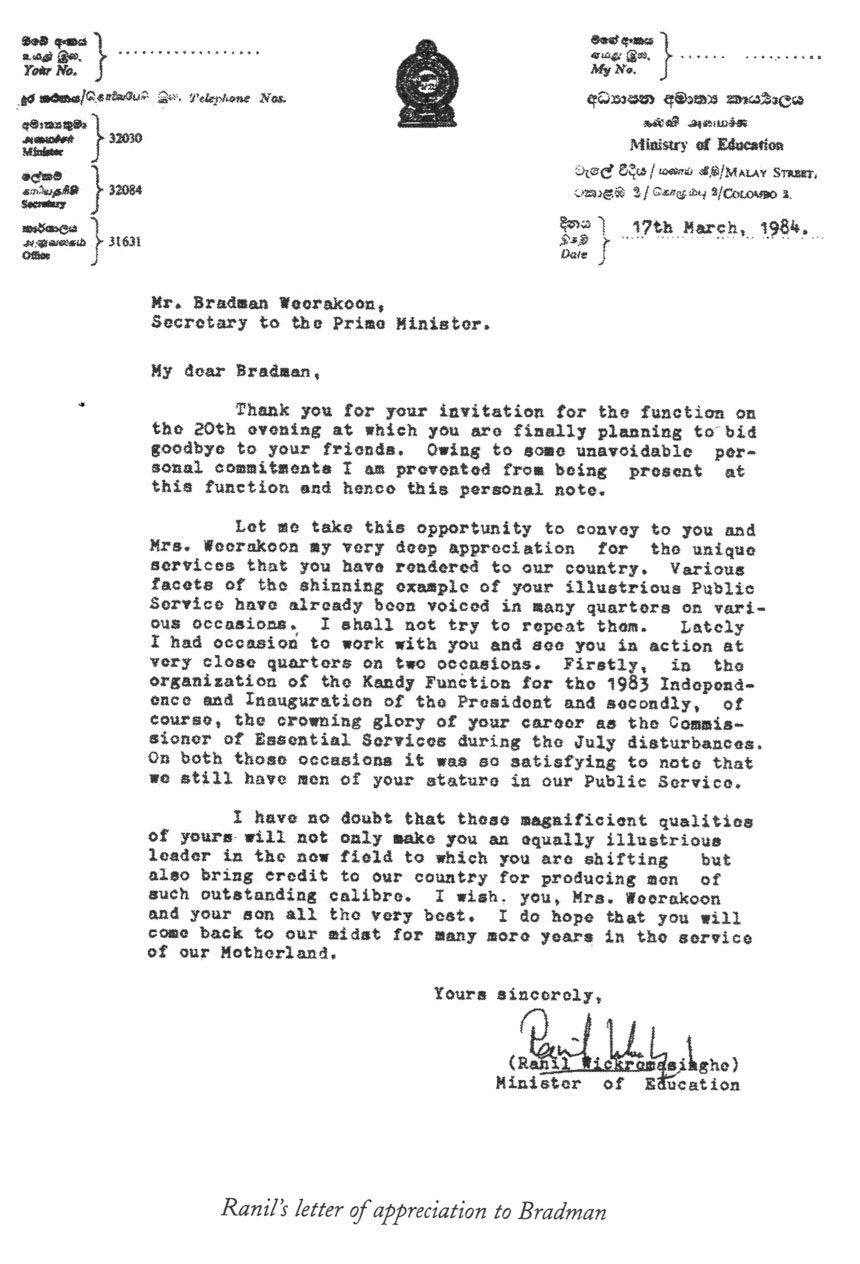

Then there was also another personal reason as to why I thought I should work for Ranil now that he had asked me to. When I left for the IPPF job in 1984, Ranil, who was then the minister of education, had written an extraordinarily nice letter of appreciation for something I had done. I reproduce this letter later in this book. I had thought it special at the time, and it had been with me all these years. The last line was close to becoming prophetic. It seemed that I now had in my final years, a chance to make it happen!

The challenge of the Peace Process

Ranil knew of the difficulties in managing something as challenging as the peace process in Sri Lanka. The LTTE was deemed at most times to be intractable with fixed goals which were unchangeable, military cadres well resourced and, over the many years of conflict, now vastly experienced in both guerrilla and conventional warfare strategies. They were being assisted by a formidable diaspora across the world.

There was a long history of the breaking of truce agreements which the LTTE had entered into with the governments of the day. How was Ranil going to achieve the impossible of transforming this group of committed fighters into becoming a peaceful partner in political negotiations; one which would not break the truce when the going gets difficult? It was a high-risk venture he was going into where others before him had paid dearly and some with their lives.

There would also be the opposition from within to contend with. Those who had said, and would continue to say, that there should be no compromise with terrorism or armed insurgency against the state. They would continue to deny the reality that beating the LTTE or any such armed force that throve on ethno-nationalism and backed by a powerful diaspora, was unachievable except at great cost. The past battles’ had proved this beyond doubt and the people had finally spoken out that they wanted peace, literally at any price.

Yet there were many who would scoff at peace through negotiations with a long-time enemy. They would include elements of the political opposition, the military, nationalist minded NGOs, the media, and the majority’ of the Sinhalese diaspora’ abroad.

Ranil conceived an approach and plan of action which would address the reality he was confronted with. He spelt it out to Parliament and the people in a broad-ranging speech he delivered on January 22, 2002. His approach’ dealt with both the domestic and international imperatives. He realized a well-founded peace process needed the following basic elements:

= An experienced facilitator who is trusted by both sides.

= An agreement in writing laying down the parameters for a durable cease-fire subscribed to by both leaders of the parties to the conflict, namely Prabhakaran, on behalf of the LTTE and himself on behalf of the government.

= An official institutional structure which could manage the manifold requirements needed to keep the negotiations between the parties on track.

= An effective mechanism to coordinate the relief, rehabilitation and development activities which would sustain the process.

To buttress and support this he would need to establish an `international safety-net’ composed of the leading nations of the world to guarantee, and intervene whenever necessary, to achieve the shared goal of a negotiated political settlement of the national problem.

It was a task of enormous proportions and there had been many political leaders who had tried and failed. In addition he had a formidable political opponent from within to contend with. He was not, as the others who had tried to bring peace before him had been, the constitutional head of government. The president of the country, Chandrika Kumaratunga was the constitutional head of state and government and although she too was in favour of peace through negotiation, she could be expected to be fastidious in the manner she would oversee Ranil’s strategy and methodology, in the name of national security, sovereignty, territorial integrity and so on.

But through it all, winning the confidence of the Norwegian facilitator, pushing through the cease-fire agreement, gaining the goodwill of the Tamil diaspora, and a considerable section of the Sinhalese as well, and securing the commitment of a powerful array of the developed countries, Ranil succeeded in making peace actually come to pass. Overall it was a magnificent display of bold and innovative strategising, tenacity of purpose, the mobilizing of a devoted team of workers and infinite patience. Only. someone with an extraordinary sense of mission could have managed all the uncertainties and imponderables which this long-endured national problem posed.

In addition to the constant presidential challenges, he had a range of domestic forces opposed to what he was doing. There was the bedrock of nationalistic feeling stemming from a long history of perception of the Tamil community as aliens and outsiders, who had literally no place in the country which belonged to the majority, the Sinhalese. A strident reflection of this opinion came from the now resurgent JVP, who were again making a strong mark in the political field. There were also a heterogeneous grouping of intellectuals, serious students of the subject, who had come to the determination that the demands of the LTTE, were too much and should never be conceded. The price of peace was in their view becoming too high to pay.

There were several media men and women, including one or two editors of mainline newspapers themselves, who regularly questioned the wisdom of embarking on a path which would inevitably end up in changing the nature of the Sri Lankan polity. In their view, and apparently a large part of the population supported their position, Sri Lanka had always” been one united state and its constitution should therefore remain immutably unitary in structure. Federalism was the `F word’ in all its possible connotations. To many of these groups, the proposed fundamental structural change (here both the president and the prime minister found agreement in opposing this line) from a unitary style constitution to one that was federal was anathema. They would regularly highlight in their editorials the dangers of several aspects of the peace process and by implication, the naivety, and in some instances even the treachery, of those engaged in the venture.

Throughout the two years process, what was unhelpful was the non-collaborative attitude that the president took. There was evident hostility at some of the actions of the Norwegian facilitator in the person of the Norwegian ambassador in Colombo and the head of mission of the monitoring force, the Sri Lanka Monitoring Mission (SLMM). These were seen as being partial and on the side of the LTTE, something that others too were saying but particularly decisive as it came from the head of the state.

The president was also said to be involved in ordering the sinking of a LTTE vessel, alleged by Anton Balasingham to be a merchant ship and at the time of attack by the Navy, in international waters. It was well known that as commander-in-chief of the three armed services, the president could give direct orders to the Navy Commander. She held the chair of the National Security Council (NSC) and remained in constant contact with the service commanders throughout the cease-fire period.

The tactic of the defence ministry virtually run by Ranil as prime minister on the other hand had been to shadow the vessel and put the international monitors on board to verify what was really on board after it moved into Sri Lankan waters. This would have enabled a verification of whether in fact, as alleged, the vessel carried arms and ammunition, or merchandise as claimed by the LTTE. There were numerous other incidents too in which the terms of the Ceasefire Agreement (CFA) were either breached or came close to being broken.

No cease-fire agreement could cover every possible eventuality that could arise and this led to an exchange between the president and her defence minister, the laconic Tilak Marapone, PC, which illustrates the sense of humour of Chandrika Kumaratunga and the bitter-sweet nature of the relationships between the president and the government.

Apparently after one particular close encounter between the LTTE and the army, which might have been regarded as a violation of the cease-fire agreement, Tilak, on being upbraided by Chandrika soon after a meeting of the National Security Council” for his lack of attention to such lapses, nonchalantly suggested that there were occasions when it was necessary to, as they say ‘turn a blind eye’ to such happenings. Quick as a flash Chandrika retorted that if that was so, it was she more than him, who could afford to do so!

It takes two to tango as the saying goes and there was much that Ranil could have done by sharing information and more consultation to change the confrontational attitude the president took about most of the actions he initiated. Ranil always countered this charge by insisting that she was being informed by their mutual friend Lakshman Kadirgamar whom he regularly met, and who was the president’s special advisor. But this was obviously no substitute to a regular face-to-face encounter between the two protagonists.

I personally felt that the president believed that the peace process which was rightfully her’s to move forward with, had been now usurped by an outsider. What was most galling was that the outsider, Ranil, was now seen to be making unexpected progress towards a settlement. She, the president, had been the originator of the negotiation approach to a political settlement. Her father, S W R D Bandaranaike had many years earlier made the first moves in this direction through the famous Bandaranaike Chelvanayakam Pact. She and her late husband Vijaya Kumaratunga had intensely believed in the negotiation approach for years.

In 1994 when she got the chance, she had, first as prime minister for a few months and later as president, initiated “Talks” by sending a delegation to Jaffna. That attempt faltered after some months and an intense period of conflict had followed. In 2000, she had come up with significant proposals in a draft constitution which was presented in Parliament.

Ranil and the UNP who had participated in some of the discussions had rejected the draft out of hand. Copies of the draft Constitution had been burnt on the floor of Parliament. Ranil was perceived by her as always being on the opposite side, inhibiting her attempts at resolution of the problem. In her view the UNP had been doing so ever since its opposition to the B-C Pact in 1957.

(Excerpted from Rendering Unto Caesar, the Bradman Weerakoon autobiography) ✍️

Features

Pakistan-Sri Lanka ‘eye diplomacy’

Reminiscences:

I was appointed Managing Director of the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC) and Chairman of the Trincomalee Petroleum Terminals Ltd (TPTL – Indian Oil Company/ Petroleum Corporation of Sri Lanka joint venture), in February 2023, by President Ranil Wickremesinghe. I served as TPTL Chairman voluntarily. TPTL controls the world-renowned oil tank farm in Trincomalee, abandoned after World War II. Several programmes were launched to repair tanks and buildings there. I enjoyed travelling to Trincomalee, staying at Navy House and monitoring the progress of the projects. Trincomalee is a beautiful place where I spent most of my time during my naval career.

My main task as MD, CPC, was to ensure an uninterrupted supply of petroleum products to the public.

With the great initiative of the then CPC Chairman, young and energetic Uvis Mohammed, and equally capable CPC staff, we were able to do our job diligently, and all problems related to petroleum products were overcome. My team and I were able to ensure that enough stocks were always available for any contingency.

The CPC made huge profits when we imported crude oil and processed it at our only refinery in Sapugaskanda, which could produce more than 50,000 barrels of refined fuel in one stream working day! (One barrel is equal to 210 litres). This huge facility encompassing about 65 acres has more than 1,200 employees and 65 storage tanks.

A huge loss the CPC was incurring due to wrong calculation of “out turn loss” when importing crude oil by ships and pumping it through Single Point Mooring Buoy (SPMB) at sea and transferring it through underwater fuel transfer lines to service tanks was detected and corrected immediately. That helped increase the CPC’s profits.

By August 2023, the CPC made a net profit of 74,000 million rupees (74 billion rupees)! The President was happy, the government was happy, the CPC Management was happy and the hard-working CPC staff were happy. I became a Managing Director of a very happy and successful State-Owned Enterprise (SOE). That was my first experience in working outside military/Foreign service.

I will be failing in my duty if I do not mention Sagala Rathnayake, then Chief of Staff to the President, for recommending me for the post of MD, CPC.

The only grievance they had was that we were not able to pay their 2023 Sinhala/Tamil New Year bonus due to a government circular. After working at CPC for six months and steering it out of trouble, I was ready to move out of CPC.

I was offered a new job as the Sri Lanka High Commissioner to Pakistan. I was delighted and my wife and son were happy. Our association with Pakistan, especially with the Pakistan Military, is very long. My son started schooling in Karachi in 1995, when I was doing the Naval War Course there. My wife Yamuna has many good friends in Pakistan. I am the first Military officer to graduate from the Karachi University in 1996 (BSc Honours in War Studies) and have a long association with the Pakistan Navy and their Special Forces. I was awarded the Nishan-e-Imtiaz (Military) medal—the highest National award by the Pakistan Presidentm in 2019m when I was Chief of Defence Staff. I am the only Sri Lankan to have been awarded this prestigious medal so far. I knew my son and myself would be able to play a quiet game of golf every morning at the picturesque Margalla Golf Club, owned by the Pakistan Navy, at the foot of Margalla hills, at Islamabad. The golf club is just a walking distance from the High Commissioner’s residence.

When I took over as Sri Lanka High Commissioner at Islamabad on 06 December 2023, I realised that a number of former Service Commanders had held that position earlier. The first Ceylonese High Commissioner to Pakistan, with a military background, was the first Army Commander General Anton Muthukumaru. He was concurrently Ambassador to Iran. Then distinguished Service Commanders, like General H W G Wijayakoon, General Gerry Silva, General Srilal Weerasooriya, Air Chief Marshal Jayalath Weerakkody, served as High Commissioners to Islamabad. I took over from Vice Admiral Mohan Wijewickrama (former Chief of Staff of Navy and Governor Eastern Province).

A photograph of Dr. Silva (second from right) in Brigadier

(Dr) Waquar Muzaffar’s album

One of the first visitors I received was Kawaja Hamza, a prominent Defence Correspondent in Islamabad. His request had nothing to do with Defence matters. He wanted to bring his 84-year-old father to see me; his father had his eyesight restored with corneas donated by a Sri Lankan in 1972! His eyesight is still good, but he did not know the Sri Lankan donor who gave him this most precious gift. He wanted to pay gratitude to the new Sri Lankan High Commissioner and to tell him that as a devoted Muslim, he prayed for the unknown donor every day! That reminded me of what my guru in Foreign Service, the late Foreign Minister Lakshman Kadirgamar told me when I was First Secretary/ Defence Advisor, Sri Lanka High Commission in New Delhi. That is “best diplomacy is people-to-people contacts.” This incident prompted me to research more into “Pakistan-Sri Lanka Eye Diplomacy” and what I learnt was fascinating!

Do you know the Sri Lanka Eye Donation Society has donated more than 26,000 corneas to Pakistan, since 1964 to date! That means more than 26,000 Pakistani people see the world with SRI LANKAN EYES! The Sri Lankan Eye Donation Society has provided 100,000 eye corneas to foreign countries FREE! To be exact 101,483 eye corneas during the last 65 years! More than one fourth of these donations was to one single country- Pakistan. Recent donations (in November 2024) were made to the Pakistan Military at Armed Forces Institute of Ophthalmology (AFIO), Rawalpindi, to restore the sight of Pakistan Army personnel who suffered eye injuries due to Improvised Explosive Devices (IED) blasts. This donation was done on the 75th Anniversary of the Sri Lanka Army.

Deshabandu Dr. F. G. Hudson Silva, a distinguished old boy of Nalanda College, Colombo, started collecting eye corneas as a medical student in 1958. His first set of corneas were collected from a deceased person and were stored at his home refrigerator at Wijerama Mawatha, Colombo 7. With his wife Iranganie De Silva (nee Kularatne), he started the Sri Lanka Eye Donation Society in 1961. They persuaded Buddhists to donate their eyes upon death. This drive was hugely successful.

Their son (now in the US) was a contemporary of mine at Royal College. I pledged to donate (of course with my parents’ permission) my eyes upon my death when I was a student at Royal college in 1972 on a Poson Full Moon Poya Day. Thousands have done so.

On Vesak Full Moon Poya Day in 1964, the first eye corneas were carried in a thermos flask filled with Ice, to Singapore, by Dr Hudson Silva and his wife and a successful eye transplant surgery was performed. From that day, our eye corneas were sent to 62 different countries.

Pakistan Lions Clubs, which supported this noble gesture, built a beautiful Eye Hospital for humble people at Gulberg, Lahore, where eye surgeries are performed, and named it Dr Hudson Silva Lions Eye Hospital.

The good work has continued even after the demise of Dr Hudson Silva in 1999.

So many people have donated their eyes upon their death, including President J. R. Jayewardene, whose eye corneas were used to restore the eyesight of one Japanese and one Sri Lankan. Dr Hudson Silva became a great hero in Pakistan and he was treated with dignity and respect whenever he visited Pakistan. My friend, Brigadier (Dr) Waquar Muzaffar, the Commandant of AFIO, was able to dig into his old photographs and send me a precious photo taken in 1980, 46 years ago (when he was a medical student), with Dr Hudson Silva.

We will remember Dr and Mrs Hudson Silva with gratitude.

Bravo Zulu to Sri Lanka Eye Donation Society!

by Admiral Ravindra C Wijegunaratne

by Admiral Ravindra C Wijegunaratne

WV, RWP and Bar, RSP, VSV, USP, NI (M) (Pakistan), ndc, psn, Bsc

(Hons) (War Studies) (Karachi) MPhil (Madras)

Former Navy Commander and Former Chief of Defense Staff

Former Chairman, Trincomalee Petroleum Terminals Ltd

Former Managing Director Ceylon Petroleum Corporation

Former High Commissioner to Pakistan

Features

Lasting solutions require consensus

Problems and solutions in plural societies like Sri Lanka’s which have deep rooted ethnic, religious and linguistic cleavages require a consciously inclusive approach. A major challenge for any government in Sri Lanka is to correctly identify the problems faced by different groups with strong identities and find solutions to them. The durability of democratic systems in divided societies depends less on electoral victories than on institutionalised inclusion, consultation, and negotiated compromise. When problems are defined only through the lens of a single political formation, even one that enjoys a large electoral mandate, such as obtained by the NPP government, the policy prescriptions derived from that diagnosis will likely overlook the experiences of communities that may remain outside the ruling party. The result could end up being resistance to those policies, uneven implementation and eventual political backlash.

A recent survey done by the National Peace Council (NPC), in Jaffna, in the North, at a focus group discussion for young people on citizen perception in the electoral process, revealed interesting developments. The results of the NPC micro survey support the findings of the national survey by Verite Research that found that government approval rating stood at 65 percent in early February 2026. A majority of the respondents in Jaffna affirm that they feel safer and more fairly treated than in the past. There is a clear improving trend to be seen in some areas, but not in all. This survey of predominantly young and educated respondents shows 78 percent saying livelihood has improved and an equal percentage feeling safe in daily life. 75 percent express satisfaction with the new government and 64 percent believe the state treats their language and culture fairly. These are not insignificant gains in a region that bore the brunt of three decades of war.

Yet the same survey reveals deep reservations that temper this optimism. Only 25 percent are satisfied with the handling of past issues. An equal percentage see no change in land and military related concerns. Most strikingly, almost 90 percent are worried about land being taken without consent for religious purposes. A significant number are uncertain whether the future will be better. These negative sentiments cannot be brushed aside as marginal. They point to unresolved structural questions relating to land rights, demilitarisation, accountability and the locus of political power. If these issues are not addressed sooner rather than later, the current stability may prove fragile. This suggests the need to build consensus with other parties to ensure long-term stability and legitimacy, and the need for partnership to address national issues.

NPP Absence

National or local level problems solving is unlikely to be successful in the longer term if it only proceeds from the thinking of one group of people even if they are the most enlightened. Problem solving requires the engagement of those from different ethno-religious, caste and political backgrounds to get a diversity of ideas and possible solutions. It does not mean getting corrupted or having to give up the good for the worse. It means testing ideas in the public sphere. Legitimacy flows not merely from winning elections but from the quality of public reasoning that precedes decision-making. The experience of successful post-conflict societies shows that long term peace and development are built through dialogue platforms where civil society organisations, political actors, business communities, and local representatives jointly define problems before negotiating policy responses.

As a civil society organisation, the National Peace Council engages in a variety of public activities that focus on awareness and relationship building across communities. Participants in those activities include community leaders, religious clergy, local level government officials and grassroots political party representatives. However, along with other civil society organisations, NPC has been finding it difficult to get the participation of members of the NPP at those events. The excuse given for the absence of ruling party members is that they are too busy as they are involved in a plenitude of activities. The question is whether the ruling party members have too much on their plate or whether it is due to a reluctance to work with others.

The general belief is that those from the ruling party need to get special permission from the party hierarchy for activities organised by groups not under their control. The reluctance of the ruling party to permit its members to join the activities of other organisations may be the concern that they will get ideas that are different from those held by the party leadership. The concern may be that these different ideas will either corrupt the ruling party members or cause dissent within the ranks of the ruling party. But lasting reform in a plural society requires precisely this exposure. If 90 percent of surveyed youth in Jaffna are worried about land issues, then engaging them, rather than shielding party representatives from uncomfortable conversations, is essential for accurate problem identification.

North Star

The Leader of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), Prof Tissa Vitarana, who passed away last week, gave the example for national level problem solving. As a government minister he took on the challenge the protracted ethnic conflict that led to three decades of war. He set his mind on the solution and engaged with all but never veered from his conviction about what the solution would be. This was the North Star to him, said his son to me at his funeral, the direction to which the Compass (Malimawa) pointed at all times. Prof Vitarana held the view that in a diverse and plural society there was a need to devolve power and share power in a structured way between the majority community and minority communities. His example illustrates that engagement does not require ideological capitulation. It requires clarity of purpose combined with openness to dialogue.

The ethnic and religious peace that prevails today owes much to the efforts of people like Prof Vitarana and other like-minded persons and groups which, for many years, engaged as underdogs with those who were more powerful. The commitment to equality of citizenship, non-racism, non-extremism and non-discrimination, upheld by the present government, comes from this foundation. But the NPC survey suggests that symbolic recognition and improved daily safety are not enough. Respondents prioritise personal safety, truth regarding missing persons, return of land, language use and reduction of military involvement. They are also asking for jobs after graduation, local economic opportunity, protection of property rights, and tangible improvements that allow them to remain in Jaffna rather than migrate.

If solutions are to be lasting they cannot be unilaterally imposed by one party on the others. Lasting solutions cannot be unilateral solutions. They must emerge from a shared diagnosis of the country’s deepest problems and from a willingness to address the negative sentiments that persist beneath the surface of cautious optimism. Only then can progress be secured against reversal and anchored in the consent of the wider polity. Engaging with the opposition can help mitigate the hyper-confrontational and divisive political culture of the past. This means that the ruling party needs to consider not only how to protect its existing members by cloistering them from those who think differently but also expand its vision and membership by convincing others to join them in problem solving at multiple levels. This requires engagement and not avoidance or withdrawal.

by Jehan Perera

Features

Unpacking public responses to educational reforms

As the debate on educational reforms rages, I find it useful to pay as much attention to the reactions they have excited as we do to the content of the reforms. Such reactions are a reflection of how education is understood in our society, and this understanding – along with the priorities it gives rise to – must necessarily be taken into account in education policy, including and especially reform. My aim in this piece, however, is to couple this public engagement with critical reflection on the historical-structural realities that structure our possibilities in the global market, and briefly discuss the role of academics in this endeavour.

As the debate on educational reforms rages, I find it useful to pay as much attention to the reactions they have excited as we do to the content of the reforms. Such reactions are a reflection of how education is understood in our society, and this understanding – along with the priorities it gives rise to – must necessarily be taken into account in education policy, including and especially reform. My aim in this piece, however, is to couple this public engagement with critical reflection on the historical-structural realities that structure our possibilities in the global market, and briefly discuss the role of academics in this endeavour.

Two broad reactions

The reactions to the proposed reforms can be broadly categorised into ‘pro’ and ‘anti’. I will discuss the latter first. Most of the backlash against the reforms seems to be directed at the issue of a gay dating site, accidentally being linked to the Grade 6 English module. While the importance of rigour cannot be overstated in such a process, the sheer volume of the energies concentrated on this is also indicative of how hopelessly homophobic our society is, especially its educators, including those in trade unions. These dispositions are a crucial part of the reason why educational reforms are needed in the first place. If only there was a fraction of the interest in ‘keeping up with the rest of the world’ in terms of IT, skills, and so on, in this area as well!

Then there is the opposition mounted by teachers’ trade unions and others about the process of the reforms not being very democratic, which I (and many others in higher education, as evidenced by a recent statement, available at https://island.lk/general-educational-reforms-to-what-purpose-a-statement-by-state-university-teachers/ ) fully agree with. But I earnestly hope the conversation is not usurped by those wanting to promote heteronormativity, further entrenching bigotry only education itself can save us from. With this important qualification, I, too, believe the government should open up the reform process to the public, rather than just ‘informing’ them of it.

It is unclear both as to why the process had to be behind closed doors, as well as why the government seems to be in a hurry to push the reforms through. Considering other recent developments, like the continued extension of emergency rule, tabling of the Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), and proposing a new Authority for the protection of the Central Highlands (as is famously known, Authorities directly come under the Executive, and, therefore, further strengthen the Presidency; a reasonable question would be as to why the existing apparatus cannot be strengthened for this purpose), this appears especially suspect.

Further, according to the Secretary to the MOE Nalaka Kaluwewa: “The full framework for the [education] reforms was already in place [when the Dissanayake government took office]” (https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2025/08/12/wxua-a12.html, citing The Morning, July 29). Given the ideological inclinations of the former Wickremesinghe government and the IMF negotiations taking place at the time, the continuation of education reforms, initiated in such a context with very little modification, leaves little doubt as to their intent: to facilitate the churning out of cheap labour for the global market (with very little cushioning from external shocks and reproducing global inequalities), while raising enough revenue in the process to service debt.

This process privileges STEM subjects, which are “considered to contribute to higher levels of ‘employability’ among their graduates … With their emphasis on transferable skills and demonstrable competency levels, STEM subjects provide tools that are well suited for the abstraction of labour required by capitalism, particularly at the global level where comparability across a wide array of labour markets matters more than ever before” (my own previous piece in this column on 29 October 2024). Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS) subjects are deprioritised as a result. However, the wisdom of an education policy that is solely focused on responding to the global market has been questioned in this column and elsewhere, both because the global market has no reason to prioritise our needs as well as because such an orientation comes at the cost of a strategy for improving the conditions within Sri Lanka, in all sectors. This is why we need a more emancipatory vision for education geared towards building a fairer society domestically where the fruits of prosperity are enjoyed by all.

The second broad reaction to the reforms is to earnestly embrace them. The reasons behind this need to be taken seriously, although it echoes the mantra of the global market. According to one parent participating in a protest against the halting of the reform process: “The world is moving forward with new inventions and technology, but here in Sri Lanka, our children are still burdened with outdated methods. Opposition politicians send their children to international schools or abroad, while ours depend on free education. Stopping these reforms is the lowest act I’ve seen as a mother” (https://www.newsfirst.lk/2026/01/17/pro-educational-reforms-protests-spread-across-sri-lanka). While it is worth mentioning that it is not only the opposition, nor in fact only politicians, who send their children to international schools and abroad, the point holds. Updating the curriculum to reflect the changing needs of a society will invariably strengthen the case for free education. However, as mentioned before, if not combined with a vision for harnessing education’s emancipatory potential for the country, such a move would simply translate into one of integrating Sri Lanka to the world market to produce cheap labour for the colonial and neocolonial masters.

According to another parent in a similar protest: “Our children were excited about lighter schoolbags and a better future. Now they are left in despair” (https://www.newsfirst.lk/2026/01/17/pro-educational-reforms-protests-spread-across-sri-lanka). Again, a valid concern, but one that seems to be completely buying into the rhetoric of the government. As many pieces in this column have already shown, even though the structure of assessments will shift from exam-heavy to more interim forms of assessment (which is very welcome), the number of modules/subjects will actually increase, pushing a greater, not lesser, workload on students.

A file photo of a satyagraha against education reforms

What kind of education?

The ‘pro’ reactions outlined above stem from valid concerns, and, therefore, need to be taken seriously. Relatedly, we have to keep in mind that opening the process up to public engagement will not necessarily result in some of the outcomes, those particularly in the HSS academic community, would like to see, such as increasing the HSS component in the syllabus, changing weightages assigned to such subjects, reintroducing them to the basket of mandatory subjects, etc., because of the increasing traction of STEM subjects as a surer way to lock in a good future income.

Academics do have a role to play here, though: 1) actively engage with various groups of people to understand their rationales behind supporting or opposing the reforms; 2) reflect on how such preferences are constituted, and what they in turn contribute towards constituting (including the global and local patterns of accumulation and structures of oppression they perpetuate); 3) bring these reflections back into further conversations, enabling a mutually conditioning exchange; 4) collectively work out a plan for reforming education based on the above, preferably in an arrangement that directly informs policy. A reform process informed by such a dialectical exchange, and a system of education based on the results of these reflections, will have greater substantive value while also responding to the changing times.

Two important prerequisites for this kind of endeavour to succeed are that first, academics participate, irrespective of whether they publicly endorsed this government or not, and second, that the government responds with humility and accountability, without denial and shifting the blame on to individuals. While we cannot help the second, we can start with the first.

Conclusion

For a government that came into power riding the wave of ‘system change’, it is perhaps more important than for any other government that these reforms are done for the right reasons, not to mention following the right methods (of consultation and deliberation). For instance, developing soft skills or incorporating vocational education to the curriculum could be done either in a way that reproduces Sri Lanka’s marginality in the global economic order (which is ‘system preservation’), or lays the groundwork to develop a workforce first and foremost for the country, limited as this approach may be. An inextricable concern is what is denoted by ‘the country’ here: a few affluent groups, a majority ethno-religious category, or everyone living here? How we define ‘the country’ will centrally influence how education policy (among others) will be formulated, just as much as the quality of education influences how we – students, teachers, parents, policymakers, bureaucrats, ‘experts’ – think about such categories. That is precisely why more thought should go to education policymaking than perhaps any other sector.

(Hasini Lecamwasam is attached to the Department of Political Science, University of Peradeniya).

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

-

Life style4 days ago

Life style4 days agoMarriot new GM Suranga

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoMonks’ march, in America and Sri Lanka

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days agoWill computers ever be intelligent?

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoThe Rise of Takaichi

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoWetlands of Sri Lanka:

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoThailand to recruit 10,000 Lankans under new labour pact

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoMassive Sangha confab to address alleged injustices against monks