Opinion

Truth and Reconciliation Commission for Sri Lanka: Issues and challenges

D. Phil. (Oxford), Ph. D. (Sri Lanka);

Rhodes Scholar, Quondam Visiting Fellow of the Universities of Oxford, Cambridge and London;

Former Vice-Chancellor and Emeritus Professor of Law of the University of Colombo.

I. The Domestic and International Setting

The establishment of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission is a matter of lively interest across our society at this time. Developments a few days ago at the international level make this issue immediately relevant to the national interest of Sri Lanka.

The Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mr. Vijitha Herath, in his address at the 58th Session of the Human Rights Commission in Geneva in February this year, expressed interest in “the contours of a strong truth and reconciliation framework” and committed his government to “strengthening the work” in this field.

Current preoccupation with this concept has both a domestic and an international impetus. Within the country, the overwhelming confidence placed by the people of the North and East, as part of an Islandwide avalanche, in the current National People Power administration, impels the Government to focus, as a matter of priority, on national healing and reconciliation.

Beyond our shores, the expectation is equally urgent. The United Nations Human Rights Council, over the last decade, has adopted no fewer than 6 Resolutions on Sri Lanka. The pivotal Resolution, co-sponsored by Sri Lanka in 2015, called for a Commission for Truth, Justice, Reconciliation and Non-Recurrence. Subsequent Resolutions, expressing concern over lack of progress and the need for international accountability, introduced a new – and potentially hazardous – dimension. This consisted of the creation of a uniquely intrusive mechanism to gather and analyse evidence relating to Sri Lanka as a launching pad for further action in international tribunals.

Against the backdrop of these initiatives, a series of legislative measures have been taken in Sri Lanka – principally the enactment of the Office of Missing Persons Act of 2016, the Office for Reparations Act of 2018 and the Office of National Unity and Reconciliation Act of 2024. However, a hiatus remains with regard to the overarching mechanism of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

In attempting to complete the edifice, it is natural that policy makers in Sri Lanka should seek to derive assistance from the experience of South Africa, the home of probably the best-known Commission of this kind in the world. Inadequately and superficially researched, the proposed Sri Lankan legislation, published in the Gazette of 29 December 2023, suffers by comparison with legislation in other countries: it is marred by glaring omissions, and reflects shallowness of understanding of the aspirations which undergird successful instruments of reconciliation in our time.

II. The South African Experience Compared

The overlapping and contrasting features of Sri Lankan and South African legislation warrant close analysis.

(a) Territorial Application

There is a crucial difference in this regard. The mandate in South Africa embraces the whole nation without qualification (Preamble and section 3 of Act No. 34 of 1995). By contrast, the proposed mandate in Sri Lanka is operative throughout the Island, but only where the atrocities in question “were caused in the course of, or reasonably connected to, or consequent to the conflict which took place in the Northern and Eastern Provinces during the period 1983 to 2009, or its aftermath” (section 12(i)).

This is a limitation which cannot but affect the completeness of the Commission’s work. For instance, among the Commission’s powers is that of applying to a Magistrate “to excavate sites of suspected graves or mass graves and to act as observers at such excavations or exhumations” (section 13 (2c)). This is relevant also to areas outside the Northern and Eastern Provinces, and curtailment of the Commission’s mandate detracts from the overall balance and value of its work.

(b) Structural Framework

The South African legislation envisages 3 Committees specifically established alongside the Commission – the Committee on Human Rights Violations, the Committee on Amnesty and the Committee on Reparation and Rehabilitation. Each of these Committees has a statutory mandate and function, the role of each being clearly defined in relation to the Commission.

The Sri Lankan Bill is much less precise and clear-cut.The corresponding provision empowers the Commission to appoint panels consisting of not less than 3 members, the members being assigned to panels by the Chairperson of the Commission (section 7(2)). Unlike in South Africa, there is no indication of either the number of panels, or the subject matter entrusted to each panel. A tighter conceptual scheme, with explicit definition of identity and scope, is desirable at this conjuncture.

(c) Reconciliation and the Judiciary

Investigation which the Commission in Sri Lanka is authorised to undertake encompasses a wide range of activity including “extrajudicial killings, assassinations and mass murders” (section 12(g)(i)), “acts of torture” (section 12(g)(ii)) and “abduction, hostage taking and enforced disappearances” (section 12(g)(iv)). These are grave crimes in respect of which proceedings are instituted before the regular courts. In this event, should judicial proceedings, of a civil or criminal nature, be suspended until conclusion of the Commission’s investigations, or vice versa, or should they take place concurrently?

This is a matter of obvious practical importance which receives detailed consideration in South Africa, but not at all in Sri Lanka. For instance, where the person seeking amnesty before the relevant Committee in South Africa has a civil action in court pending against him, he may request suppression of the proceedings pending disposal of the application before the Committee (section 19(6)). The court may, after hearing all relevant parties, accede to this request. Similarly, a criminal action may be postponed in consultation with the Attorney-General of the relevant Province. These provisions serve the salutary purpose of averting the risk of conflicting orders by the courts and a Committee of the Commission in simultaneous proceedings. The Sri Lankan Bill fails to make any provision against this unacceptable contingency.

(d) Protection and Compellability

Discovery of truth requires the compulsory attendance of witnesses and the production of evidence before the Commission or its delegate. There is a the equally critical need, in subsequent proceedings, to protect witnesses against incrimination by testimony obtained through compulsion. These are competing objectives which need to be reconciled equitably.

This is achieved by the South African legislation: a person will be compelled to answer or produce evidentiary material having the potential to incriminate him, only if the Commission is satisfied that this course of action is “reasonable, necessary and justifiable” (section 31(2)). Moreover, the vital proviso is attached that the incriminating answer or evidence is inadmissible in criminal proceedings against the person providing it. This is a satisfactory result.

The position in Sri Lanka is quite otherwise. There is provision for the Commission to summon any person or to procure material (section 13(t) and (u)). This exists side by side with provision empowering the Attorney-General “to institute criminal proceedings in respect of any offence based on material collected in the course of an investigation by the Commission” (section 16(2)). Vulnerability is enhanced by the removal of protection conferred by the Evidence Ordinance (section 13(y)). In stark contrast with the position in South Africa, there is singular absence of any provision against self-incrimination in Sri Lanka.

(e) Amnesty

The basic purpose of Truth and Reconciliation Commissions around the world is to enable victims to come to terms with a deeply scarred past and to face the future with dignity and self-assurance. This is the gist of the Greek concept of Katharsis, or purging of the soul. Through full and candid disclosure, involving unburdening and relief, comes the expiation of guilt.

This is the context in which the idea of amnesty occupies a central place in the scheme of reconciliation. The Committee on Amnesty is the centrepiece of South African legislation. The primacy of its function is underlined by the provision that “No decision, or the process of arriving at such a decision, of the Committee on Amnesty shall be reviewed by the

Commission” (section 5(e)). The status of this Committee is unique, standing as it does apart from, and indeed above, the other Committees. An application for amnesty succeeds in South Africa if there is genuine contrition manifested in complete disclosure of all relevant facts (section 20(i)).

Sri Lankan law takes an entirely different course. Although the proposed Bill postulates, as one of the main objectives of the Commission “providing the people of Sri Lanka with a platform for truth telling” (section 12(d)), no provision whatever is made for conferment of amnesty in consequence of uninhibited disclosure. At the core of the law, there is a policy contradiction, with practical implications.

III. Political Will

Apart from these infirmities, cumulatively worrying, there is a negative factor of far greater importance.

When the draft legislation in Sri Lanka was published in January 2024, the response was less than unreservedly enthusiastic. This was mainly because of lingering doubts about the strength of political will underpinning this initiative. By no means the initial overture, this was yet another step in a long and disheartening sequence of events. The Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission, the Udalagama Commission and the Paranagama Commission represented together a sterile endeavour, for well over a decade, to address the salient issues. The Bill impliedly concedes this. What is of particular significance is the inclusion, in Part VIII of the Bill, of a set of provisions entitled “Implementation of the Commission’s Recommendations”. The key provision requires the setting up of a Monitoring Committee (section 39) consisting of the Secretaries of 5 Ministries and 6 others, to submit to the President every 6 months reports which “shall include the reasons for non-implementation” (section 40(9)) by relevant entities. This is hardly likely to engender a high threshold of confidence.

A critical component of political will is commitment to community participation. This was much in evidence in South Africa even before Nelson Mandela’s accession to the Presidency. In my academic career, during visits to the University of the Witwatersrand and the University of Cape Town on lecture tours, I observed at first hand, the sustained efforts by leaders of South African academia to convince the corporate sector that structural change is the preferable alternative to unbridled anarchy.

As Minister of Justice, Ethnic Affairs and National Integration in the Government of President Chandrika Kumaratunga, I interacted closely with my counterparts,Dullah Omar, Minister of Justice and Mandela’s personal lawyer and Valli Moosa, Minister of Constitutional Affairs, who even used pictorial images, rather than the printed word, to convey the central message of reconciliation to the vast mass of the people, especially in the rural hinterland. This was very much the wind beneath the wings, and supplied the thrust for intense community involvement.

IV. Role of an Icon

Rising above all these considerations is a circumstance which was brought home to me vividly during my participation, as Minister of Foreign Affairs, in the Commonwealth Summit in Kigali, Rwanda, in 2022. On the sidelines of this event, I had the benefit of a discussion with my South African counterpart, Ms. Naledi Pandor, at the time Minister of International Relations and Cooperation. She shared with me her perspective that, whatever the South African process accomplished, was in considerable measure attributable to the towering stature of Archbishop Desmond Tutu who enjoyed remarkable prestige across the nation. An emblematic figure as the visible symbol of the process is, therefore, vital, the ideal choice probably being a personality bereft of a prominent political profile. Qualities of leadership are, in practice, of even greater value than the structural characteristics of the Commission.

V. Restorative Justice

The abiding inspiration of reconciliation mechanisms arises from the idea of restorative, as opposed to retributive, justice; but this concept has intrinsic limits. In the South African case, pride of place was given to sincere truth telling which would overcome hatred and the primordial instinct for revenge. The vehicle for giving effect to this was amnesty. Not infrequently, however, this opportunity was spurned. Despite the personal intervention of Mandela, former State President P. W. Botha was adamant in his refusal to appear before the Commission which he denounced as “a fierce unforgiving assault” on Afrikaaners. This sentiment struck a compliant chord in many leaders of the security and military establishment under the apartheid regime. Among them were General Magnus Malan, former Minister of Defence, and General Johan van der Merwe, former Commissioner of the South African Police.

Contemptuous refusal to appear before the Commission led to criminal prosecution. Eugene de Kock, commander of a police death squad, was convicted on multiple counts of murder. An interesting case is that of Security Branch officer, Joao Rodrigues, who was charged with murder 47 years after the death of anti-apartheid activist, Ahmed Timol, in police custody. When repentance and amnesty failed, criminal responsibility took over.

At the heart of the discourse is interplay among the ideas of truth, justice and reconciliation. Search for the right balance is the perennial dilemma. The basic conflict is between amnesty and accountability. A legitimate criticism of the South African experience is that it tended, on occasion, to give disproportionate attention to the former at the expense of the latter. It did happen that grave crimes went unpunished, leaving victims, after the trauma of reliving the past, profoundly unfulfilled.

Diverse cultures offer an array of choices. In Argentina, the power to grant amnesty was withheld from the Commission. In Colombia, disclosure resulted not in total exoneration but in mitigation of sentence. In Chile, prosecutions were feasible only after a prolonged interval since the dismantling of Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship. In Peru, individual sanctions were studiedly relegated to major economic and societal transformation in the wake of the ravaging conflict with Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path).

An eclectic approach, affording the fullest scope for selection and imaginative adaptation, is the way forward. There is no size that fits all.

By Professor G. L. Peiris

Opinion

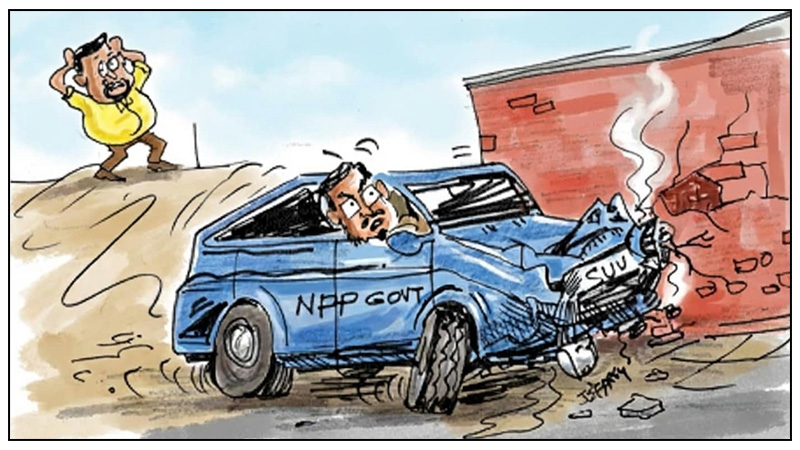

Ranwala crash: Govt. lays bare its true face

The NPP government is apparently sinking into a pit dug by the one of its members, ‘Dr’ Asoka Ranwala; perhaps a golden pit (Ran Wala) staying true to his name! Some may accuse me of being unpatriotic by criticising a government facing the uphill task of rebuilding the country after an unprecedented catastrophe. Whilst respecting their sentiment, I cannot help but point out that it is the totally unwarranted actions of the government that is earning much warranted criticism, as well stated in the editorial “Smell of Power” (The Island, 15 December). Cartoonist Jeffrey, in his brilliance, has gone a step further by depicting Asoka Ranwala as a giant tsunami wave rushing to engulf the tiny NPP house in the shore, AKD is trying to protect. (The Island, 18 December).

The fact that Asoka Ranwala is very important to the JVP, for whatever reason, became evident when he was elected the Speaker of Parliament despite his lack of any parliamentary experience. When questions were raised about his doctorate in Parliament, Ranwala fiercely defended his position, ably supported by fellow MPs. When the Opposition kept on piling pressure, producing evidence to the contrary, Ranwala stepped aside, claiming that he had misplaced the certificate but would stage a comeback, once found. A year has passed and he is yet to procure a copy of the certificate, or even a confirmatory letter from the Japanese university!

The fact that AKD did not ask Ranwala to give up his parliamentary seat, a decision he may well be regretting now following recent events, shows that either AKD is not a strong leader who can be trusted to translate his words to action or that Ranwala is too important to be got rid of. In fact, AKD should have put his foot down, as it was revealed that Ranwala was a hypocrite, even if not a liar. Ranwala led the campaign to dismantle the private medical school set up by Dr Neville Fernando, which was earning foreign exchange for the country by recruiting foreign students, in addition to saving the outflow of funds for educating Sri Lankan medical graduates abroad. He headed the organisation of parents of state medical students, claiming that they would be adversely affected, and some of the photographs of the protests he led refer to him as Professor Ranwala! Whilst leading the battle against private medical education, Ranwala claims to have obtained his PhD from a private university in Japan. Is this not the height of hypocrisy?

The recent road traffic accident he was involved in would have been inconsequential had Ranwala been decent enough to leave his parliamentary seat or, at least, being humble enough to offer an apology for his exaggerated academic qualifications. After all, he is not the only person to have been caught in the act of embellishing a CV. As far as the road traffic accident is concerned, too, it may not be his entire responsibility. Considering the chaotic traffic, in and around Colombo, coupled with awful driving standards dictated by lack of patience and consideration, it is a surprise that more accidents do not happen in Sri Lanka. Following the accident, may be to exonerate from the first count, a campaign was launched by NPP supporters stating that a man should be judged on his achievements, not qualifications, further implying that he does not have the certificate because he got it in a different name!

What went wrong was not the accident, but the way it was handled. Onlookers claim that Ranwala was smelling of alcohol but there is no proof yet. He could have admitted it even if he had taken any alcohol, which many do and continue to drive in Sri Lanka. After all, the Secretary to the Ministry overseeing the Police was able to get the charge dropped after causing multiple accidents while driving under the influence of liquor! He, with another former police officer, sensing the way the wind was blowing formed a retired police collective to support the NPP and were adequately rewarded by being given top jobs, despite a cloud hanging over them of neglect of duty during the Easter Sunday attacks. This naïve political act brought the integrity of the police into question. The way the police behaved after Ranwala’s accident confirmed the fears in the minds of right-thinking Sri Lankans.

In the euphoria of the success of a party promising a new dawn, unfortunately, many political commentators kept silent but it is becoming pretty obvious that most are awaking to the reality of a false dawn. It could not have come at a worse time for the NPP: in spite of the initial failures to act on the warnings regarding the devastating effects of Ditwah, the government was making good progress in sorting problems out, when Ranwala met with an accident.

The excuses given by the police for not doing a breathalyser test, or blood alcohol levels, promptly, are simply pathetic. Half-life of alcohol is around 4-5 hours and unless Ranwala was dead drunk, it is extremely unlikely any significant amounts of alcohol would be detected in a blood sample taken after 24 hours. Maybe the knowledge of this that made government Spokesmen to claim boldly that proper action would be taken irrespective of the position held. Now that the Government Analyst has not found any alcohol in the blood, no action is needed! Instead, the government seems to have got the IGP to investigate the police. Would any police officers suffer for doing a favour to the government? That is the million-dollar question!

Unfortunately, all this woke up a sleeping giant; a problem that the government hoped would be solved by the passage of time. If the government is hoping that the dishonesty of one of its prominent members would be forgotten with the passage of time, it will be in for a rude shock. When questioned by journalists repeated, the Cabinet spokesman had to say action would be taken if the claim of the doctorate was false. However, he added that the party has not decided what that action would be! What about the promise to rid Parliament of crooks?

It is now clear that the NPP government is not any different from the predecessors and that Sri Lankan voters are forced to contend with yet another false dawn!

by Dr Upul Wijayawardhana ✍️

Opinion

Ceylon pot tea: redefining value, sustainability and future of global tea

The international tea industry is experiencing one of the most difficult periods in its history. Producers worldwide are caught in a paradox: tea must be made “cheaper than water” to stay competitive, yet this very race to the bottom erodes profitability, weakens supply chains, and drives away the most talented professionals whose expertise is essential for innovation. At the heart of this crisis lies the structure of commodity tea pricing. Although the auction system has served the world for over a century, it has clear limitations. It rewards volume rather than innovation, penalises differentiation, and leaves little room for value-added product development.

Sri Lanka, one of the world’s finest tea origins, feels this pressure more intensely than most. The industry’s traditional reliance on auctions prevents it from accessing the full premium that its authentic climate, terroir, and craftsmanship deserve. The solution is not to dismantle auctions—because they maintain transparency and global trust—but to evolve beyond them. For tea to thrive again, Ceylon Tea must enter the product market, where brand value, wellness benefits, and consumer experience define price—not weight.

Sri Lanka’s Unique Comparative Advantage

Sri Lanka possesses both competitive and comparative advantage unmatched by any other tea-producing nation. One of the least-discussed scientific advantages is its low gravitational pull, enabling the tea plant to circulate nutrients differently and produce a uniquely delicate, flavour-rich leaf. This natural phenomenon, combined with diverse microclimates, gives Sri Lankan tea extraordinary antioxidant density, rich polyphenols, and a full sensory profile representative of the land and its people.

However, this advantage is undermined by weaknesses in basic agronomy. Most estates do not use soil augers, and soil sampling is often inconsistent or unscientific. This leads to overuse of artificial fertilizer, underinvestment in regenerative practices, and weak soil organic matter (SOM). Without scientific soil management, even a world-class tea origin can lose its competitive edge. Encouragingly, discussions are already underway with the Assistant Indian High Commissioner in Kandy to explore sourcing 3,000 scientifically engineered soil augers for Sri Lanka’s perennial agriculture sector—a transformative step toward soil intelligence and sustainable input management.

Improving SOM, moderating fertilizer misuse, and systematically diagnosing soil nutrient deficiencies represent true sustainability—not cosmetic commitments. Plantation agriculture, which supports over one million Sri Lankan livelihoods, depends on this shift.

The Real Economic Challenge: Price per Kilogram

The most urgent sustainability problem is not climate change or labour cost—it is the low price per kilogram Sri Lanka receives for its tea. Nearly 20% of the tea leaf becomes “refuse tea”, a stigmatized fraction that still contains antioxidants and valuable nutrients but fetches a low price at auctions. The system inherently undervalues almost a fifth of the raw material.

A rational solution is to market the entire tea leaf without discrimination, transforming every component—tender leaf, mature leaf, fiber, and fines—into a premium product with a minimum retail value of USD 15 per kilogram. Achieving this requires product innovation, not further cost reduction.

Ceylon Pot Tea: A Transformative Opportunity

Ceylon Pot Tea emerges as a comprehensive solution capable of addressing long-standing structural issues in Sri Lanka’s tea industry. Unlike traditional tea grades, Pot Tea compresses the entire fired dhool into a high-value cube, similar to the global success of soup cubes. Every part of the leaf is represented, unlocking maximum biochemical utilisation and offering consumers a fuller taste profile with richer aroma, deeper colour, and higher antioxidant content.

Pot Tea is perfectly aligned with the health and wellness market, one of the fastest-growing global consumer segments. As an Herbal Medicinal Beverage (HMB), it captures the complete phytonutritional matrix of the tea leaf, including polyphenols, catechins, and climate-influenced compounds unique to Ceylon. The product also offers storytelling power: every cube reflects the terroir, the gentle fingers that plucked the leaf, and the mystical nature of tea grown in a land with unusually low gravitational intensity.

Already, international partners—particularly in Russia—and domestic innovators have expressed enthusiasm. Pot Tea aligns closely with the policy direction set by the Hon. Samantha Vidyarathne and the NPP Government, especially the national goal of achieving 400 million Kgs of national annual production per year by unlocking new value chains and premium product categories.

Why Immediate Government Intervention Is Necessary

For Sri Lanka to fully benefit from Ceylon Pot Tea and other modernized value chains, the government must urgently introduce:

1. Minimum Yield Benchmarks per hectare (3-year targets) for all perennial crops, informed by scientific investment appraisals.

2. A classification shift from “plantations” to land-based investment enterprises, recognising the capital-intensive, long-term nature of tea cultivation.

3. Incentives for soil testing, soil auger adoption, and SOM improvement programs.

4. Support for value-added tea manufacturing and export diversification.

These steps would create an enabling environment for Pot Tea to scale rapidly and position Sri Lanka as the world’s leading innovator in tea-based wellness products.

Way Forward: Positioning Ceylon Pot Tea for Global Leadership

The path ahead requires a coordinated national and industry-level effort. Sri Lanka must shift from simply producing tea to designing tea experiences. Ceylon Pot Tea can lead this transformation if:

1. Branding and Certification Are Strengthened

CCT (Ceylon Certified Tea) standards must be universally adopted to guarantee purity, origin authenticity, and ethical production practices.

2. Research, Soil Science & Agronomy Are Modernized

With scientific soil audits, optimized fertigation, and regenerative agriculture, Sri Lanka can unlock higher yields and stronger biochemical profiles in its leaf.

3. A Global Wellness Narrative Is Created

Position Pot Tea as a nutritional, therapeutic, anti-aging, and calming beverage suited for the modern lifestyle.

4. Export Market Activation Begins Immediately

Pilot shipments, influencer partnerships, and cross-border digital campaigns should begin with Russia, the Middle East, Japan, and premium EU markets.

5. Producers Are Incentivised to Convert Dhools to Cubes

This ensures minimal waste, improved margins, and equitable value distribution across the supply chain.

Conclusion: A New Dawn for Ceylon Tea

Ceylon Pot Tea offers Sri Lanka a rare chance to pivot from a commodity-driven past to a premium, wellness-oriented, high-margin future. It aligns economic sustainability with environmental responsibility. It empowers estate communities with modern agronomy. And most importantly, it transforms every gram of the tea leaf into value—finally rewarding the land, the planter, and the plucker.

If implemented with vision and urgency, Ceylon Pot Tea will not only revitalise an industry under immense pressure but also secure Sri Lanka’s place as the world’s most innovative and scientifically grounded tea nation.

By. Dammike Kobbekaduwe

(www.vivonta.lk & www.planters.lk) ✍️

Opinion

Lakshman Balasuriya – simply a top-class human being

It is with deep sorrow that I share the passing of one of my dearests and most trusted friends of many years, Lakshman Balasuriya. He left us on Sunday morning, and with him went a part of my own life. The emptiness he leaves behind is immense, and I struggle to find words that can carry its weight.

Lakshman was not simply a friend. He was a brother to me. We shared a bond built on mutual respect, quiet understanding, and unwavering trust. These things are rare in life, and for that reason they are precious beyond measure. I try to remind myself that I was privileged to spend the final hours of his life with him, but even that thought cannot soften the ache of his sudden and significant absence.

Not too long ago, our families were on holiday together. Lakshman and Janine returned to Sri Lanka early. The rest of the holiday felt a bit empty without Lakshman’s daily presence. I cannot fathom how different life itself will be from now on.

He was gentle and a giant in every sense of the word. A deeply civilized man, refined in taste, gracious in manner, and extraordinarily humble. His humility was second to none, and yet it was never a weakness. It was strength, expressed through kindness, warmth, and dignity. He carried himself with quiet class and had a way of making everyone around him feel at ease.

Lakshman had a very dry, almost deadpan, sense of humor. It was the kind of humor that would catch you off guard, delivered with too straight a face to be certain he was joking, but it could lighten the darkest of conversations. He had a disdain for negativity of any kind. He preferred to look forward, to see possibilities rather than obstacles.

He was exceptionally meticulous and had a particular gift for identifying talent. Once he hired someone, he made sure they were cared for in unimaginable ways. He provided every resource needed for success, and then, with complete trust, granted them independence and autonomy. His staff were not simply employees to him. They were family. He took immense pride in them, and his forward-thinking optimism created an environment of extraordinary positivity and a passion to deliver results and do the right thing.

Lakshman was also a proud family man. He spoke often, and with great pride, about his children, grandchildren, nephews, and nieces. His joy in their achievements was boundless. He was a proud father, grandfather, and uncle, and his devotion to his family reflected the same loyalty he extended to his colleagues and friends.

Whether it was family, staff, or anyone he deemed deserving, Lakshman stood by them unconditionally in times of crisis. He would not let go until victory was secured. That was his way. He was a uniquely kind soul through and through.

Our bond was close. Whenever I arrived in Sri Lanka, it became an unspoken ritual that we would meet at least twice. The first would be on the day of my arrival, and then again on the day I left. It was our custom, and one I cherished deeply. We met regularly, and we spoke almost daily. He was simply a top-class human being. We were friends. We were brothers. His passing has devastated me.

Today I understood fully the true meaning of the phrase ‘priyehi vippaogo dukkho’ — (ප්රියෙහි විප්පයෝගෝ දුක්ඛෝපෝ) ‘separation from those who are beloved is sorrowful.’

My thoughts and prayers are with Janine, Amanthi, and Keshav during this time of profound loss. Lakshman leaves behind indelible memories, as well as a legacy of decency, loyalty, and quiet strength. All of us who were fortunate to know him will hold that legacy close to our hearts.

If Lakshman’s life could leave us with just one lesson, that lesson would be this. True greatness is not measured in titles or possessions, but in the way one treats others: with humility, with loyalty, with kindness that does not falter in times of crisis. Lakshman showed us that to stand by someone, to believe in them, and to lift them up when they falter, is the highest of callings, and it was a calling he never failed to honour.

Rest well, my dear friend.

Krishantha Prasad Cooray

-

Midweek Review6 days ago

Midweek Review6 days agoHow massive Akuregoda defence complex was built with proceeds from sale of Galle Face land to Shangri-La

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoPope fires broadside: ‘The Holy See won’t be a silent bystander to the grave disparities, injustices, and fundamental human rights violations’

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoPakistan hands over 200 tonnes of humanitarian aid to Lanka

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoUnlocking Sri Lanka’s hidden wealth: A $2 billion mineral opportunity awaits

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoBurnt elephant dies after delayed rescue; activists demand arrests

-

News10 hours ago

News10 hours agoMembers of Lankan Community in Washington D.C. donates to ‘Rebuilding Sri Lanka’ Flood Relief Fund

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoColombo Port facing strategic neglect

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoArmy engineers set up new Nayaru emergency bridge