Opinion

Devolution and Comrade Anura

By Austin Fernando

(Former Secretary to the President)

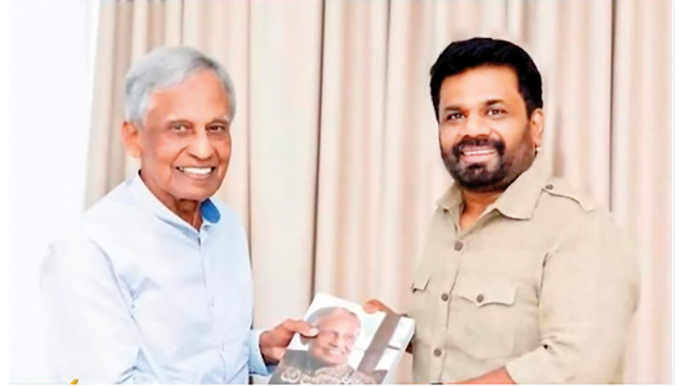

About ten months ago, among other things, I informally discussed the devolution of power with Anura Kumara Dissanayake, who was an MP at the time. The consequences of his low-priority approach to devolution, as predicted then, were reflected in the presidential election results in the North and the East. Perhaps, there were other reasons also for the low level of popular support for him over there. Now that he is the President of 23 million Sri Lankans, he must consider the presidential election results in the North and the East as a guide. Probably, the Indian External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar has already reminded him of that.

Sri Lankan politicians’ mood changes

The policies of Sri Lankan politicians on power sharing are characterized by inconsistencies. Former Ministers Basil Rajapaksa and Prof. G.L. Peiris promised Indians the implementation of the 13th Amendment (13A). Though Namal Rajapaksa has specifically rejected the devolution of Land and Police powers, President Mahinda Rajapaksa promised “13A+,” including those. In Delhi, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa said 13A could not be implemented “against the wishes and feelings of the majority (Sinhala) community.” But he had solemnly declared that he would uphold and defend the Constitution, of which 13A is an integral part! The Indian political leaders’ policy on the devolution here has remained consistent.

We have conveniently forgotten that during the Oslo Peace Talks on 05 December 2002, the Sri Lankan delegation led by G. L. Peiris and the LTTE delegation led by Anton Balasingham agreed to “explore a solution founded on the principle of internal self-determination in areas of historical habitation of the Tamil-speaking peoples, based on a federal structure, within a united Sri Lanka.”

“Federal,” “areas of historical habitation,” and “internal self-determination” are anathema to many Southern politicians and not understood by civilians. Today, Ranil Wickremesinghe and Pieris will certainly dissociate themselves from the Oslo Declaration.

Wickremesinghe, who supported the passage of 13A and appurtenant legislations, was Prime.

Minister (PM) when the Oslo Declaration was made. But now he is unwilling to devolve police powers to Provincial Councils (PCs). Gotabhaya Rajapaksa informed Indians that he must “look at weaknesses and strengths of 13A.” Had he said so as an inexperienced President in 2019, it would have been tolerable, but he said so after 22 months in office. It reflected a lack of knowledge of governance systems on his part or something up his sleeve.

Evolution of 13A

In this background, it is appropriate, to reflect the evolution of 13A to evaluate it as against what was demanded in the name of devolution.

Sri Lanka came under pressure to devolve power following Black July (1983) and the beginning of the armed conflict. The contention that the Indians wished for Sri Lanka’s division through devolution is not true. India has always respected our sovereignty and territorial integrity owing to its experience with conflicts in Mizoram, Nagaland, etc.

On 01 March 1985, President J. R. Jayewardene personally sought Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s intervention to prevent the movement of armed terrorists from India and Sri Lankans seeking refuge in India. On 01 December 1985, the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) presented its proposals for devolution to Gandhi in a bid to pressure Sri Lanka to agree to power-sharing.

The salient features of the proposal were as follows:

• Sri Lanka—”Ilankai” be a union of states,

• Amalgamated Northern and Eastern Provinces, a ‘Tamil Linguistic State’, which cannot be altered without their consent,

• Parliament reflecting ethnic proportion shall be empowered to make laws under “List 1″ for Defense, Foreign Affairs, Currency, Posts / Telecommunications, Immigration/Emigration, Foreign trade/Commerce, Railways, Airports /Aviation, Broadcasting/Television, Customs, Elections, and Census only, • List 2” had all other subjects, inclusive of Law and Order, Land, etc., with the State Assembly possessing law-making powers, • Any person resident in Sri Lanka, on 1st November 1981, who is not a foreigner shall be a Sri ankan citizen, • No Resolution or Bill affecting any “nationality” should be passed by Parliament without the agreement of that “nationality,” (The term ‘nationality’ is misleading.)

• The State Assembly to be empowered to levy taxes, cess/fees, and mobilize loans/grants,

• Special provisions for Indian Tamils,

• The elected members are to be given enhanced powers, • Upgrading the judicial system, e.g. Provincial High Court to Appeal Court, and, • Muslim rights to be cared for.

The Jayewardene Government rejected the proposal out of hand. The TULF again addressed Gandhi (17-1-1986), incorporating more sensitive issues such as ‘traditional homelands,’ demographic imbalance, etc. Jayewardene steadfastly advocated a military solution and the war was dubbed as “genocide” by former Indian Minister B.R. Bhagat and several Lok Sabha members. The latter demanded punitive interventions such as ‘crushing Sri Lanka in 24 hours” (Sri Kolandaivelu on 29-4-1985), and Sri Gopalaswamy on 13-5-1985, asking India “to undertake every possible means, including military interventions.”

Gandhi would have been satisfied with the Sri Lankan proposals of 09 July 1986, prepared after consulting Minister P. Chidambaram, which fitted the Sri Lankan constitutional basics. There were ‘Notes’ incorporated into the proposals on PCs, law and order, and land settlements inclusive of land alienation under the Mahaweli Project, with allottees identified based on ethnicity. On 30 Sept.,

1986, the TULF responded to India in detail to the government’s proposals, adding more propositions.

Gandhi was mindful of Lok Sabha’s demands. He vented frustration in Lok Sabha and abroad (e.g. Harare). Efforts to project him and India as weak exasperated him and drove him to get tough. On 02 June 1987, he threatened to send a flotilla with ‘humanitarian assistance’, and on 04 June 1987, Indian Aircraft violated Sri Lanka’s airspace and carried out aid drops in the North. No superpower stood with us on this blatant violation. No wonder Jayewardene agreed to sign an Accord and follow up by introducing 13A.

After the signing of the Accord, the Indian Peace Keeping Forces (IPKF) were deployed in Sri Lanka.

Lt. General A. S. Kalkat, in an interview with Nithin Ghokle, has admitted that the deployment of the Indian army here was a mistake. Jaishankar (one-time political adviser to the IPKF- 1988-1990), has said in his ‘The India Way,’ that it was a ‘misadventure.’ We are aware of the IPKF’s ‘mistakes’ and ‘misadventures’ like the Valvettithurai Massacre of 64 persons on 02 August 1989, and more, best known to Kalkat and Jaishankar. Importantly, the IPKF operations instilled fear, especially conditioning Tamil people’s minds to search for whatever possible solution.

Concurrently, as explained by then-Indian Foreign Secretary A. P. Venkateswaran, Jayewardene met Gandhi in mid-November 1986 in Bangalore, along with Ministers Natwar Singh, Chidambaram, and himself, and Jayewardene allegedly ‘pleaded’ with Gandhi to send the Indian Army to prevent his government from collapsing, due to the JVP attacks in the South, and LTTE in the North. It was his sheer desperation that drove Jayewardene to opt for the Accord and 13A. After this meeting, Gandhi sent Chidambaram and Natwar Singh to Colombo knowing our vulnerability.

On 19 December 1986, they submitted the “emerged” proposals. The salient points were as follows:

* The Eastern Province to be demarcated minus Sinhala majority Ampara Electorate.

* A PC was to be established for the new Eastern Province.

* Earlier discussed institutional linkages to be refined for Northern and Eastern PCs. The

intention would have been to merge later under a second-stage constitutional development.

* Sri Lanka was willing to create a Vice Presidency for a specified term.

* The five Muslim parliamentarians from the Eastern Province may be invited to India to discuss matters of mutual concern.

The foregoing demands show how India tried to match the Tamils’ interest, vis-a-vis the wishes of the majority community.

Military operations continued provoking India, which threatened to abandon its intervenor role on 09 February 1987, unless Colombo pursued a political solution. Jayewardene responded on 12 February 1987, insinuating calming down on military actions, promoting negotiation and administration, and paving the release of persons in custody. This was how India reacted when rubbed wrongly.

Under successive governments, PCs were weakened by the withdrawal of powers and lacked cooperation. This may have led Jaishankar to address President Dissanayake, whose party is considered averse to 13A. This is the perception of the Tamil MPs, who have recently sought US Ambassador Julie Chung’s intervention for correction. Such aversion to PCs is hard to overcome as evident from an NPP’s public statement that devolution will not include Land and Police powers. It said so close on the heels of Jaishankar’s request that 13A be fully implemented.

Flashback to 1986

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) stalwart, Jaswant Singh posed seven questions in Lok Sabha on 13 May 1986, based on the situation in Sri Lanka. They are relevant even today.

* What is the Indian stand in the debate on devolution and delegation?

* Where do India and Sri Lanka stand on the Northern and Eastern Provinces merger?

* What is the stand on land use by the Indian Government, the Government of Sri Lanka, and

the Tamil groups?

* What is the status of the language?

* What is the stand on Law and Order?

* What is the time frame for reaching a solution?

* What is the Indian Government’s stand on the foreign threats emerging in the context of the Sri Lankan issues?

If Jaswant Singh were alive today, he would either join the critical Lok Sabha Members or question PM Modi and Jaishankar why the Accord has not been implemented. Jaishankar’s reminder to President Dissanayake would have been due to his frustration stemming from:

* 13A being “paralyzed” by partial implementation, and delayed elections.

* The demerger of the North and the East legally

* The delay in devolving land and police powers

* The language issue has not been fully resolved despite constitutional guarantees

* Absence of a timeframe for a solution, even after crushing the Tigers in 2009, and,

* Increasing threat to India, especially from China.

Parallelly, the field situations have changed. Military operations have ceased. Public attention has been shifted from conflict to human rights and humanitarian concerns, returning refugees, and reconciliation. 13A has been internationalized owing to the incorporation thereof into UNHRC Resolutions by Mahinda Rajapaksa and Wickremesinghe in 2009 and 2015 respectively. Intense lobbying by Diaspora groups has also contributed to this situation. These are daunting challenges before President Dissanayake. 13A is only one of them.

What is in store?

As seen above, the 13A has trudged a rough path to be accepted domestically or in India. Parliamentarians resigned, opposition politicians and Bhikkus protested on roads against it and violence was experienced. If the rejected proposals had been accepted the consequences would have been disastrous. However, devolution has come to stay and is viewed as a ‘Made-in-India’ solution.

President Dissanayake must be prepared for negotiations with relevant parties on devolution and hence needs to study India’s experience with devolution. For instance, on the devolution of land powers, Dissanayake can refer to how the Indian government changed Jammu Kashmir rules allowing the center to release lands to Indians to attract development/investment. They permitted even non-residents to own immovable property in Jammu and Kashmir and transfer agricultural land for non-agricultural purposes. India considered changes as her “internal affairs”, which may not be acceptable to them if we say so on 13A!

PM Modi has declared that such abrogation brought about security, dignity, and opportunity for all communities that had been deprived of development, and helped eliminate corruption. If he wishes, President Dissanayake can make similar reasoning to bolster his arguments concerning devolution.

Indians also have asymmetrical administration in the Himachal and Uttarakhand States but do not apply that to Jammu-Kashmir, which we also could duplicate. However, asymmetrical devolution is extremely complex and warrants serious legal attention.

It is now up to President Dissanayake’s legal and administrative experts to propose how to

incorporate propositions concerning devolution into the proposed new Constitution. India might compromise on devolution and concentrate more on economic and humanitarian rights interventions. Such attitudinal change is the need of the hour.

Indian National Security Advisor Ajit Doval, a respected negotiator/strategist, recognised even by Chinese President Xi Jinping in Kazan, has advised Tamil politicians to negotiate with a winnable candidate and secure Tamil aspirations through negotiations. His wise counsel was not heeded by some Tamil politicians, who, while rejecting 13A, demanded a federal system with self-determination powers for Tamils, which is a non-starter. By reminding President Dissanayake of the need to implement 13A after Doval’s visit, New Delhi sent a clear message concerning Sri Lanka: that it does not consider self-determination or a federal system as a solution.

Hence, Tamil politicians also must revise their approach in light of the aforesaid message. Based on Jaswant Singh’s queries and current political trends, if Tamil groups reject 13A, a new power-sharing mechanism sans federalism must be proposed. Perhaps, the new Constitution promised by Dissanayake may offer an alternative to bring about nation-building, with equality, dignity, justice, self-respect, and inclusivity, through a political process. They are the crux of Tamil demands.

Some believe that devolution can be achieved through Local Government Authorities in contravention of international norms of devolution and the Principle of Subsidiarity. Additionally, making all political parties think out of the box is a formidable challenge. Yet, consensual decision-making is needed to ensure the sustainability of any mechanism.

Meera Srinivasan of The Hindu has said:

“Despite India’s known support to the Mahinda Rajapaksa administration in defeating the LTTE in 2009, sections among the Sri Lankan southern population remain India-sceptics, wary of the big neighbour, who ‘interfered’ in Sri Lanka’s ethnic conflict, ‘sided with Tamils’. They resist India’s commenting on power devolution or conduct of elections to PCs and oppose any Indian role in developing national assets.”

India and the Tamil political establishment may adapt to this Sinhala mindset. The upcoming parliamentary election is expected to enable the NPP to form a government. If so, it will be timely to change narratives, without risking the redirection of the government’s political allegiances elsewhere. India should be cautious. Change should be achieved through wider consultations and agreements.

From Bhandari to Vikram Mistri, and Rajeev Gandhi to Narendra Modi, Indians also have acted like their Sri Lankan counterparts in managing the national question here, as evident from Sri Lanka’s failure to implement the 13A fully for 37 years, and India’s failure to convince Sri Lanka of the need to use 13A to solve the national question.

Today India has to deal with a Sri Lankan leader, who is different from predecessors. It is hoped that Jaishankar and others will be able to persuade him to get to the genuine track to explore a solution for the national question. Good luck to Ministers Subrahmanyam Jaishankar and Vijitha Herath, Secretaries Vikram Mistri and Aruni Wijewardane, and High Commissioners Santhosh Jha and Kshenuka Senevirathe!

Opinion

English as used in scientific report writing

The scientific community in the English-speaking world publishes its research findings using technical and scientific English (naturally!). It has its own particular vocabulary. Many words are exclusive for a particular technology as they are specialised technical terms. Also, the inclusion in research papers of mathematical and statistical terms and calculations is important where they support the overall findings.

There is a whole array of specialist publications, journals, papers and letters serving the scientific community world-wide. These publications are by subscription only but can easily be found in university libraries upon request.

Academics quote the number of their research papers published with pride. They are the status symbols of personal achievement par excellence! And most importantly, these are used to help justify the continuation of funding for the upcoming academic year.

Such writings are carefully crafted works of precision and clarity. Not a word is out of place. All words used are nuanced to fit exactly the meaning of what the authors of the paper wish to convey. No word is superfluous (= extra, not needed); all is well manicured to convey the message accurately to a knowledgeable, receptive reader. As a result, people from all around the world are using the Internet to access these research findings thus establishing the English language as a major form of information dissemination.

Reporting is best when it is measurable and can be quantified. Figures mean a lot in the scientific world. Sizes, quantities, ranges of acceptance, figures of probability, etc., all are used to lend authority to the research findings.

Before a paper can be accepted for publication it must be submitted to a panel for peer review. This is where several experts in the subject or speciality form a panel to assess the work and approve or reject it. Careers depend on well-presented reports.

Preparation Before Starting Research

There is a standard procedure for a researcher to follow before any practical work is done. It is necessary to evaluate the current status of work in this subject. This requires reading all the relevant, available literature, books, papers, etc., on this subject. This is done for the student to get ‘up to speed’ and in tune with the preceding research work in this field. During this process new avenues for research and investigation may open up for investigation.

Much research is done incorporating the ‘design of experiments’ statistical approach. Research these days rely heavily on statistics to prove an argument and the researcher has to be familiar and conversant with these statistical techniques of inquiry and evaluation to add weight to his or her findings.

We are all much richer due to the investigations done in the English-speaking world by the investigative scientific community using English as a tool of communication. In scientific research, the best progress in innovation, it seems, is when students can all collaborate. Then the best ideas develop and come out.

Sri Lankans should not exclude themselves from this process of knowledge creation and dissemination. Sri Lanka needs to enter this scientific world and issue its own publications in good English. Sri Lanka needs experts who have mastered this form of scientific communication and who can participate in the progress of science!

The most wonderful opportunities open up from time to time for graduates of the STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) mainly in companies using modern technology. The reputation of Sri Lanka depends on having a horse in this race – quite apart from the need to provide suitable careers for its own population. People have ambitions and need to be able rise up intellectually and get ahead. Therefore, students in the STEM subjects need to be able to read, analyse and compare several different research papers, i.e., students need to have critical thinking skills – in English. Often, these skills have to be communicated. Students need to be able to write to this high standard of English.

Students need to be able to put their thoughts on paper in a logical, meaningful way, their thoughts backed up by facts and figures according to the principles of the academic, research world. But natural speakers of English have difficulties in mastering this type of English and doing analyses and critical thinking – therefore, it must be multiple times more difficult for Sri Lankans to master this specialised form if English. Therefore, special attention needs to be paid to overcoming this disadvantage.

In addition, the researcher needs to have knowledge of the “design of experiments,” and be familiar with everyday statistics, e.g., the bell curve, ranges of probability, etc.

How can this high-quality English (and basic stats) possibly be taught in Sri Lanka when most campuses focus on the simple passing of grammar exams?

Sri Lanka needs teachers with knowledge of this advanced, specialist form of English supported with statistical “design of experiments” knowledge. Secondly, this knowledge has to be organised and systematized and imparted over a sufficient time period to students with ability and maturity. Over to you NIE, Maharagama!

by Priyantha Hettige

Opinion

Sri Lanka, the Stars,and statesmen

When President J. R. Jayewardene stood at the White House in 1981 at the invitation of U.S. President Ronald Reagan, he did more than conduct diplomacy; he reminded his audience that Sri Lanka’s engagement with the wider world stretches back nearly two thousand years. In his remarks, Jayewardene referred to ancient explorers and scholars who had written about the island, noting that figures such as Pliny the Elder had already described Sri Lanka, then known as Taprobane, in the first century AD.

Pliny the Elder (c. AD 23–79), writing his Naturalis Historia around AD 77, drew on accounts from Indo-Roman trade during the reign of Emperor Claudius (AD 41–54) and recorded observations about Sri Lanka’s stars, shadows, and natural wealth, making his work one of the earliest Roman sources to place the island clearly within the tropical world. About a century later, Claudius Ptolemy (c. AD 100–170), working in Alexandria, transformed such descriptive knowledge into mathematical geography in his Geographia (c. AD 150), assigning latitudes and longitudes to Taprobane and firmly embedding Sri Lanka within a global coordinate system, even if his estimates exaggerated the island’s size.

These early timelines matter because they show continuity rather than coincidence: Sri Lanka was already known to the classical world when much of Europe remained unmapped. The data preserved by Pliny and systematised by Ptolemy did not fade with the Roman Empire; from the seventh century onward, Arab and Persian geographers, who knew the island as Serendib, refined these earlier measurements using stellar altitudes and navigational instruments such as the astrolabe, passing this accumulated knowledge to later European explorers. By the time the Portuguese reached Sri Lanka in the early sixteenth century, they sailed not into ignorance but into a space long defined by ancient texts, stars, winds, and inherited coordinates.

Jayewardene, widely regarded as a walking library, understood this intellectual inheritance instinctively; his reading spanned Sri Lankan chronicles, British constitutional history, and American political traditions, allowing him to speak of his country not as a small postcolonial state but as a civilisation long present in global history. The contrast with the present is difficult to ignore. In an era when leadership is often reduced to sound bites, the absence of such historically grounded voices is keenly felt. Jayewardene’s 1981 remarks stand as a reminder that knowledge of history, especially deep, comparative history, is not an academic indulgence but a source of authority, confidence, and national dignity on the world stage. Ultimately, the absence of such leaders today underscores the importance of teaching our youth history deeply and critically, for without historical understanding, both leadership and citizenship are reduced to the present moment alone.

Anura Samantilleke

Opinion

General Educational Reforms: To what purpose? A statement by state university teachers

One of the major initiatives of the NPP government is reforming the country’s education system. Immediately after coming to power, the government started the process of bringing about “transformational” changes to general education. The budgetary allocation to education has been increased to 2% of GDP (from 1.8% in 2023). Although this increase is not sufficient, the government has pledged to build infrastructure, recruit more teachers, increase facilities at schools and identified education reforms as an urgent need. These are all welcome moves. However, it is with deep concern that we express our views on the general education reforms that are currently underway.

The government’s approach to education reform has been hasty and lacking in transparency and public consultation. Announcements regarding the reforms planned for January 2026 were made in July 2025. In August, 2025, a set of slides was circulated, initially through unofficial sources. It was only in November 2025, just three months ahead of implementation, that an official policy document, Transforming General Education in Sri Lanka 2025, was released. The Ministry of Education held a series of meetings about the reforms. However, by this time the modules had already been written, published, and teacher training commenced.

The new general education policy shows a discrepancy between its conceptual approach and content. The objectives of the curriculum reforms include: to promote “critical thinking”, “multiple intelligences”, “a deeper understanding of the social and political value of the humanities and social sciences” and embed the “values of equity, inclusivity and social justice” (p. 9). Yet, the new curriculum places minimal emphasis on social sciences and humanities, and leaves little time for critical thinking or for molding social justice-oriented citizens. Subjects such as environment, history and civics, are left out at the primary level, while at the junior secondary level, civics and history are allocated only 10 and 20 hours per term. The increase in the number of “essential subjects” to 15 restricts the hours available for fundamentals like mathematics and language; only 30 hours are allocated to mathematics and the mother tongue, per term, at junior secondary level. Learning the second national language and about our conflict-ridden history are still not priorities despite the government’s pledge to address ethnic cohesion. The time allocation for Entrepreneurship and Financial Literacy, now an essential subject, is on par with the second national language, geography and civics. At the senior secondary level (O/L), social sciences and humanities are only electives. If the government is committed to the objectives that it has laid out, there should be a serious re-think of what subjects will be taught at each grade, the time allocated to each, their progress across different levels, and their weight in the overall curriculum.

A positive aspect of the reforms is the importance given to vocational training. A curriculum that recognises differences in students, whether in terms of their interest in subject matter, styles of learning, or their respective needs, and caters to those diverse needs, would make education more pluralistic and therefore democratic. However, there must be some caution placed on how difference is treated, and this should not be reflected in vocational training alone, but in all aspects of the curriculum. For instance, will the history curriculum account for different narratives of history, including the recent history of Sri Lanka and the histories of minorities and marginalised communities? Will the family structures depicted in textbooks go beyond conventional conceptions of the nuclear family? Addressing these areas too would allow students to feel more represented in curricula and enable them to move through their years of schooling in ways that are unconstrained by stereotypes and unjust barriers.

The textbooks for the Grade 6 modules on the National Institute of Education (NIE) website appear to have not gone through rigorous review. They contain rampant typographical errors and include (some undeclared) AI-generated content, including images that seem distant from the student experience. Some textbooks contain incorrect or misleading information. The Global Studies textbook associates specific facial features, hair colour, and skin colour, with particular countries and regions, and refers to Indigenous peoples in offensive terms long rejected by these communities (e.g. “Pygmies”, “Eskimos”). Nigerians are portrayed as poor/agricultural and with no electricity. The Entrepreneurship and Financial Literacy textbook introduces students to “world famous entrepreneurs”, mostly men, and equates success with business acumen. Such content contradicts the policy’s stated commitment to “values of equity, inclusivity and social justice” (p. 9). Is this the kind of content we want in our textbooks?

The “career interest test” proposed at the end of Grade 9 is deeply troubling. It is inappropriate to direct children to choose their career paths at the age of fourteen, when the vocational pathways, beyond secondary education, remain underdeveloped. Students should be provided adequate time to explore what interests them before they are asked to make educational choices that have a bearing on career paths, especially when we consider the highly stratified nature of occupations in Sri Lanka. Furthermore, the curriculum must counter the stereotyping of jobs and vocations to ensure that students from certain backgrounds are not intentionally placed in paths of study simply because of what their parents’ vocations or economic conditions are; they must also not be constrained by gendered understandings of career pathways.

The modules encourage digital literacy and exposure to new communication technologies. On the surface, this initiative seems progressive and timely. However, there are multiple aspects such as access, quality of content and age-appropriateness that need consideration before uncritical acceptance of digitality. Not all teachers will know how to use communication technologies ethically and responsibly. Given that many schools lack even basic infrastructure, the digital divide will be stark. There is the question of how to provide digital devices to all students, which will surely fall on the shoulders of parents. These problems will widen the gap in access to digital literacy, as well as education, between well-resourced and other schools.

The NIE is responsible for conceptualising, developing, writing and reviewing the general education curriculum. Although the Institution was established for the worthy cause of supporting the country’s general education system, currently the NIE appears to be ill-equipped and under-staffed, and seems to lack the experience and expertise required for writing, developing and reviewing curricula and textbooks. It is clear by now that the NIE’s structure and mandate need to be reviewed and re-invigorated.

In light of these issues, the recent Cabinet decision to postpone implementation of the reforms for Grade 6 to 2027 is welcome. The proposed general education reforms have resulted in a backlash from opposition parties and teachers’ and student unions, much of it, legitimately, focusing on the lack of transparency and consultation in the process and some of it on the quality and substance of the content. Embedded within this pushback are highly problematic gendered and misogynistic attacks on the Minister of Education. However, we understand the problems in the new curriculum as reflecting long standing and systemic issues plaguing the education sector and the state apparatus. They cannot be seen apart from the errors and highly questionable content in the old curriculum, itself a product of years of reduced state funding for education, conditionalities imposed by external funding agencies, and the consequent erosion of state institutions. With the NPP government in charge of educational reforms, we had expectations of a stronger democratic process underpinning the reforms to education, and attention to issues that have been neglected in previous reform efforts.

With these considerations in mind, we, the undersigned, urgently request the Government to consider the following:

* postpone implementation and holistically review the new curriculum, including at primary level.

* adopt a consultative process on educational reforms by holding public sittings across the country .

* review the larger institutional structure of the educational apparatus of the state and bring greater coordination within its constituent parts

* review the NIE’s mandate and strengthen its capacity to develop curricula, such as through appointexternal scholars an open and transparent process, to advise and review curriculum content and textbooks.

* consider the new policy and curriculum to be live documents and make space for building consensus in policy formulation and curriculum development to ensure alignment of the curriculum with policy.

* ensure textbooks (other than in language subjects) appear in draft form in both Sinhala and Tamil at an early stage so that writers and reviewers from all communities can participate in the process of scrutiny and revision from the very beginning.

* formulate a plan for addressing difficulties in implementation and future development of the sector, such as resource disparities, teacher training needs, and student needs.

A.M. Navaratna Bandara,

formerly, University of Peradeniya

Ahilan Kadirgamar,

University of Jaffna

Ahilan Packiyanathan,

University of Jaffna

Arumugam Saravanabawan,

University of Jaffna

Aruni Samarakoon,

University of Ruhuna

Ayomi Irugalbandara,

The Open University of Sri Lanka.

Buddhima Padmasiri,

The Open University of Sri Lanka

Camena Guneratne,

The Open University of Sri Lanka

Charudaththe B.Illangasinghe,

University of the Visual & Performing Arts

Chulani Kodikara,

formerly, University of Colombo

Chulantha Jayawardena,

University of Moratuwa

Dayani Gunathilaka,

formerly, Uva Wellassa University of Sri Lanka

Dayapala Thiranagama,

formerly, University of Kelaniya

Dhanuka Bandara,

University of Jaffna

Dinali Fernando,

University of Kelaniya

Erandika de Silva,

formerly, University of Jaffna

G.Thirukkumaran,

University of Jaffna

Gameela Samarasinghe,

University of Colombo

Gayathri M. Hewagama,

University of Peradeniya

Geethika Dharmasinghe,

University of Colombo

F. H. Abdul Rauf,

South Eastern University of Sri Lanka

H. Sriyananda,

Emeritus Professor, The Open University of Sri Lanka

Hasini Lecamwasam,

University of Peradeniya

(Rev.) J.C. Paul Rohan,

University of Jaffna

James Robinson,

University of Jaffna

Kanapathy Gajapathy,

University of Jaffna

Kanishka Werawella,

University of Colombo

Kasun Gajasinghe, formerly,

University of Peradeniya

Kaushalya Herath,

formerly, University of Moratuwa

Kaushalya Perera,

University of Colombo

Kethakie Nagahawatte,

formerly, University of Colombo

Krishan Siriwardhana,

University of Colombo

Krishmi Abesinghe Mallawa Arachchige,

formerly, University of Peradeniya

L. Raguram,

University of Jaffna

Liyanage Amarakeerthi,

University of Peradeniya

Madhara Karunarathne,

University of Peradeniya

Madushani Randeniya,

University of Peradeniya

Mahendran Thiruvarangan,

University of Jaffna

Manikya Kodithuwakku,

The Open University of Sri Lanka

Muttukrishna Sarvananthan,

University of Jaffna

Nadeesh de Silva,

The Open University of Sri Lanka

Nath Gunawardena,

University of Colombo

Nicola Perera,

University of Colombo

Nimal Savitri Kumar,

Emeritus Professor, University of Peradeniya

Nira Wickramasinghe,

formerly, University of Colombo

Nirmal Ranjith Dewasiri,

University of Colombo

P. Iyngaran,

University of Jaffna

Pathujan Srinagaruban,

University of Jaffna

Pavithra Ekanayake,

University of Peradeniya

Piyanjali de Zoysa,

University of Colombo

Prabha Manuratne,

University of Kelaniya

Pradeep Peiris,

University of Colombo

Pradeepa Korale-Gedara,

formerly, University of Peradeniya

Prageeth R. Weerathunga,

Rajarata University of Sri Lanka

Priyantha Fonseka,

University of Peradeniya

Rajendra Surenthirakumaran,

University of Jaffna

Ramesh Ramasamy,

University of Peradeniya

Ramila Usoof,

University of Peradeniya

Ramya Kumar,

University of Jaffna

Rivindu de Zoysa,

University of Colombo

Rukshaan Ibrahim,

formerly, University of Jaffna

Rumala Morel,

University of Peradeniya

Rupika S. Rajakaruna,

University of Peradeniya

S. Jeevasuthan,

University of Jaffna

S. Rajashanthan,

University of Jaffna

S. Vijayakumar,

University of Jaffna

Sabreena Niles,

University of Kelaniya

Sanjayan Rajasingham,

University of Jaffna

Sarala Emmanuel,

The Open University of Sri Lanka

Sasinindu Patabendige,

formerly, University of Jaffna

Savitri Goonesekere,

Emeritus Professor, University of Colombo

Selvaraj Vishvika,

University of Peradeniya

Shamala Kumar,

University of Peradeniya

Sivamohan Sumathy,

formerly, University of Peradeniya

Sivagnanam Jeyasankar,

Eastern University Sri Lanka

Sivanandam Sivasegaram,

formerly, University of Peradeniya

Sudesh Mantillake,

University of Peradeniya

Suhanya Aravinthon,

University of Jaffna

Sumedha Madawala,

University of Peradeniya

Tasneem Hamead,

formerly, University of Colombo.

Thamotharampillai Sanathanan,

University of Jaffna

Tharakabhanu de Alwis,

University of Peradeniya

Tharmarajah Manoranjan,

University of Jaffna

Thavachchelvi Rasan,

University of Jaffna

Thirunavukkarasu Vigneswaran,

University of Jaffna

Timaandra Wijesuriya,

University of Jaffna

Udari Abeyasinghe,

University of Peradeniya

Unnathi Samaraweera,

University of Colombo

Vasanthi Thevanesam,

Professor Emeritus, University of Peradeniya

Vathilingam Vijayabaskar,

University of Jaffna

Vihanga Perera,

University of Sri Jayewardenepura

Vijaya Kumar,

Emeritus Professor, University of Peradeniya

Viraji Jayaweera,

University of Peradeniya

Yathursha Ulakentheran,

formerly, University of Jaffna.

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoClimate risks, poverty, and recovery financing in focus at CEPA policy panel

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoSri Lanka, the Stars,and statesmen

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoHayleys Mobility ushering in a new era of premium sustainable mobility

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoAdvice Lab unveils new 13,000+ sqft office, marking major expansion in financial services BPO to Australia

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoArpico NextGen Mattress gains recognition for innovation

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoAltair issues over 100+ title deeds post ownership change

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoSri Lanka opens first country pavilion at London exhibition

-

Editorial3 days ago

Editorial3 days agoGovt. provoking TUs