Opinion

Navigating course of education reforms in SL: Past challenges and future directions – II

by Prof. M.W. Amarasiri de Silva

While the UGC represented a milestone in education management, the evolution of Sri Lanka’s higher education system did not stop there. Over time, subsequent governments introduced further reforms, each with its unique goals and objectives. These efforts have been driven by the belief that continuous improvement and adaptation in education are necessary to meet the changing needs of society, the economy, and the job market.

Despite the diverse range of committees and programmes proposed and implemented, the goal remains to enhance the quality of higher education in Sri Lanka and nurture a skilled, knowledgeable, and innovative workforce that can contribute effectively to the country’s development.

Although establishing the UGC was a significant milestone and continues to be a crucial institution in guiding and shaping higher education, it has not been able to deliver the expected objectives. Recognising the evolving challenges and opportunities, successive governments have introduced various other reforms, demonstrating an unwavering dedication to fostering a robust education system that can drive the country’s progress and prosperity in the modern era.

The special Select Committee’s recommendations proposed by the Minister of Higher Education on developing higher education should be considered from this perspective. They are aimed at significant reforms in the educational landscape in Sri Lanka. The key proposal is abolishing the University Grants Commission (UGC) and establishing an independent “National Higher Education Commission” through new legislation. This move is likely driven by the need for a more efficient, transparent, and adaptable regulatory body to oversee and enhance the higher education sector.

The proposed management committees play a crucial role in the functioning of the new higher education system, as viewed by the Minister. Let’s delve into each committee’s purpose:

State University Committee: This committee will oversee and manage state-funded universities. It will ensure that these institutions are efficiently run, adequately funded, and adhere to the government’s educational policies and guidelines.

Non-State University Committee: This committee’s responsibility is to regulate and manage privately funded universities and colleges. Its primary concerns will be ensuring quality standards, preventing exploitation, and promoting fair practices in the private education sector.

Vocational Education Institutions Committee: With a growing emphasis on vocational education to bridge the skills gap and promote employability, this committee will develop and oversee vocational institutions. These institutions will be pivotal in preparing students for specific careers and industries.

Quality Assurance Sub-committee: This sub-committee’s role is paramount as it will monitor and ensure the quality of education across all higher education institutions, whether state-funded or private. This sub-committee will help maintain and enhance the overall educational standards by implementing rigorous evaluation standards.

In addition to the suggested management committees, the proposal highlights the need for subject committees focusing on specific academic disciplines. These subject committees would be responsible for revising and updating the syllabi to align with the government’s development efforts. This recognition indicates the importance of keeping educational content relevant and adaptable to meet the evolving needs of society and the job market.

The government can ensure that the curricula reflect the latest advancements in their respective fields by having specialised subject committees or Quality Assurance Sub-committees, such as those for medicine, engineering, arts, and others. This will help produce well-prepared graduates with the skills necessary to contribute effectively to the nation’s development goals.

While administration in the university setting is recognised as necessary, the proposed reforms suggest that the urgent issue lies in updating and modernising the educational content and structure. By creating the National Higher Education Commission and implementing these various committees, the government aims to address the pressing challenges and opportunities in the higher education sector, ultimately bolstering the country’s educational standards and fostering growth and development in all fields of study. But what is the crux of the matter? As far as Medicine, Engineering, and Sciences are concerned, there is no issue with the employability of graduates.

The disciplines of arts and humanities have long been integral to university education. Still, they have faced criticism regarding their ability to produce quality graduates suitable for the country’s development efforts. Some perceive arts and humanities graduates as lacking proficiency in English and computer literacy; both are considered crucial skills for participating in development initiatives in the modern era. However, it is critical to recognize that despite these criticisms, arts and humanities faculties often have a significant number of students compared to other faculties.

The call for reforms in arts and humanities education is driven by the desire to make these disciplines more relevant and valuable in the country’s overall development. Enhancing the quality and content of arts and humanities programs aims to produce graduates with the necessary skills, knowledge, and adaptability to contribute effectively to the nation’s development goals.

Looking back to the 1950s, the arts faculty significantly produced versatile graduates who played pivotal roles in state organizations as eminent permanent secretaries and administrators. These skilled civil servants were essential in running the country’s administrative machinery. Notable individuals such as Bradman Weerakoon, Ronnie de Mel, Bandu de Silva, Sarath Amunugama, and others emerged from the arts faculty. They left a lasting mark on Sri Lanka’s governance and administration.

Moreover, the arts faculty also nurtured intellectuals, including scholars like Malalasekera and Sarachchandra in earlier times, and Obeyesekere, Sugathapala de Silva, and Siri Gunasinghe, who held prestigious professorships in renowned universities. These intellectuals made significant contributions to their respective fields of study, elevating the reputation and impact of arts and humanities education in Sri Lanka.

In addition to producing prominent figures in administrative and academic realms, the arts faculty has fostered numerous individuals who have contributed to developing arts and humanities subjects. Their knowledge, research, and creative contributions have enriched these fields, highlighting the significance of arts and humanities in preserving and advancing cultural heritage and intellectual exploration.

While there may be criticisms and challenges in the perception of arts and humanities education, it is essential to acknowledge its historical significance and the achievements of its graduates. The proposed reforms aim to build upon this strong foundation and address the perceived shortcomings by equipping arts and humanities students with language proficiency, computer skills, and other contemporary requirements.

By revitalising arts and humanities education to meet the demands of the modern era, the country can continue to produce graduates who possess critical thinking, creativity, and a deep understanding of culture, society, and human expression. Such graduates can play crucial roles in diverse sectors, contribute to policymaking, engage in cultural preservation, and contribute to the overall development and progress of the nation. The reforms seek to reaffirm the value and relevance of arts and humanities education in Sri Lanka’s evolving education landscape.

The decline in the success of the present education system, particularly in producing intellectuals comparable to those in the 1950s, can be attributed to several significant changes that occurred in the aftermath of Sri Lanka’s independence. In the post-colonial era, the importance of the English language was still recognised, and it continued to be taught as a crucial medium of communication and education.

However, alongside English, there was a deliberate emphasis on teaching Pali, Sanskrit, and Sinhala languages and literature. These subjects were considered vital for shaping the national identity and became fundamental cornerstones of the education system.

During this period, a group of intellectuals emerged, with interests spanning various cultural domains, including philosophy, arts, drama, novels, literature, and language. Their expertise in Pali, Sanskrit, and English and their knowledge of traditional Sinhalese literature allowed them to fill the cultural void at the time. They played a pivotal role in producing material related to Sinhalese culture, which later became essential in defining the Sinhalese national character.

However, the education reforms that followed the 1950s significantly changed the system. The introduction of Swabhasha medium teaching, which emphasised teaching in the native language (Sinhala and Tamil), aimed to increase accessibility and inclusion of students from rural areas into the higher education system. This expansion was laudable in providing opportunities to a broader population segment but had unintended consequences.

One of the negative impacts of this Swabhasha medium teaching was that it led to a decline in the intellectual acumen of the graduates compared to their counterparts in the 1950s. The new graduates lacked the same level of international understanding and proficiency in English, which had been a crucial component of the intellectual skills exhibited by the previous generation.

The reduced exposure to English as a medium of instruction limited their ability to engage with global perspectives and advancements in various fields. As a result, the intellectual capabilities of the graduates in the post-reform era were perceived to have declined, hindering their ability to make significant contributions at an international level. This situation was further exacerbated by the 1971 insurrection, which some scholars argue was partly a consequence of the intellectual decline caused by the educational policy changes.

In conclusion, the decline in producing intellectuals comparable to those in the 1950s can be attributed to the shift in focus towards swabhasha medium teaching and the subsequent reduction in the emphasis on English proficiency. While expanding the higher education system to include a more diverse student population was commendable, the unintended consequences of the reforms impacted the intellectual understanding and international engagement of graduates. Recognizing the importance of a balanced approach, future reforms should strive to strike a balance between promoting native language and cultural identity while ensuring students have the language and skills to thrive on a global stage.

The objective of the reform intended by the Minister of Education remains unclear. Is it to tackle the employability concerns of arts and humanities graduates? Alternatively, one might ponder whether the committees appointed by the Minister of Higher Education can restore the former splendour of arts and humanities. Nevertheless, the real challenge lies in designing Sri Lanka’s education platform to align with the global environment. From this standpoint, it becomes crucial to question whether our syllabuses and subjects taught in arts and humanities can be modernized to meet present-day demands.

One of the crucial areas requiring attention in the reforms is the revitalization of arts and humanities to address the challenges confronted by the country. Currently, the arts and humanities lack a connection with the country’s development agenda, particularly in linking with village communities. The 25,000 villages across Sri Lanka face numerous problems that hinder their progress. Issues such as the drug and alcohol menace, dengue fever, kidney disease, leptospirosis affecting the impoverished and marginalized populations, the rising rates of suicides and divorces, the increasing number of youths choosing to become monks and priests, and the growing population of unmarried individuals are all interrelated expressions of a more profound social dilemma. To effectively tackle these challenges, universities should study these issues and propose reasonable solutions. By doing so, arts and humanities can play a pivotal role in contributing to the overall development and well-being of the nation.

I propose introducing a community studies program, specifically within sociology and anthropology programs at universities in Sri Lanka. Such a program aims to involve arts and humanities students in studying issues faced by village communities, incorporating the communities themselves in a participatory approach. By doing so, the program can tap into the unique perspectives and solutions that the people in these villages have regarding their challenges.

In the United States, arts and humanities departments in universities have long-standing Community Studies programs that focus on social problems from a social justice perspective, integrating classroom learning with extended field studies. Students enrolled in these programs collaborate with non-governmental and governmental organizations, actively working on addressing these community issues. As a result, these programs have not only been successful in tackling the identified problems, but they have also created employment opportunities for social science graduates.

Adopting a similar approach in Sri Lanka, the proposed community studies program could foster a more inclusive and solution-oriented approach to societal challenges, benefiting both the students and the communities they engage with.

I am convinced that addressing the employability issue of arts and humanities graduates can be achieved by creating innovative opportunities within universities. A crucial step in this process would be the introduction of Information Technology (IT) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) as subjects within the arts and humanities curriculum, with a strong emphasis on learning English as the medium of teaching and communication. This initiative can potentially provide valuable employment prospects for arts and humanities graduates.

Integrating IT and AI into social science subjects can lead to remarkable advancements in the field of study, unlocking a plethora of opportunities for students. To implement this, the program should commence at the high school level, allowing students to study these subjects alongside other social science subjects for both Ordinary Level and Advanced Level examinations. Adequate training and recruitment of qualified teaching staff should be carried out to ensure the success of this endeavour.

Notably, these proposed changes do not necessitate the establishment of new committees or the introduction of a new organization to replace the University Grants Commission (UGC). Instead, they can be effectively integrated into the existing university framework, bringing about transformative opportunities for arts and humanities students without extensive bureaucratic changes.

Opinion

Sri Lanka Cricket needs a bitter pill

A systemic diagnosis of a fading legacy

The outcome of the 2026 T20 World Cup, coupled with the trajectory of the sport in recent years, provides harrowing evidence that Sri Lankan cricket is suffering from a terminal malignancy.The Doomsday clock for Sri Lankan cricket has not just started ticking—it has reached its final hour.

Therefore this note is written to call the attention of the cricketing elite who love the sport.

The current state of affairs suggests a pathology so deep-seated that conventional remedies—be it revolving-door coaching changes or fleeting, opportunistic victories—can no longer arrest its spread.

What we are witnessing is not a mere slump in form or a temporary lapse in rhythm; it is a profound systemic collapse that threatens the very foundation of our national pastime.

The Illusion of Recovery: The “Sanath Factor” as Palliative Care:

Since late 2024, the appointment of Sanath Jayasuriya as Head Coach injected a much-needed surge of adrenaline into the national side.

Statistically, the highlights were historic: a first ODI series win against India in 27 years, a Test victory at The Oval after a decade, and a clinical 2-0 whitewash of New Zealand.

However, a data-driven autopsy reveals that these will be “palliative” successes rather than a cure.

Under Jayasuriya’s tenure, the team maintained a win rate of approximately 50 percent (29 wins in 60 matches).

While analysts optimistically labeled this a “transitional phase,” the recent T20 series against England and Pakistan exposed the raw truth: in high-pressure “crunch” moments, the team’s performance metrics—specifically Strike Rate (SR) and Fielding Efficiency—regress to amateur levels.

We are not transitioning; we are stagnating in a professional abyss.

The Scientific Gap:

Why India and Australia Lead

The disparity between Sri Lanka and global giants such as the BCCI and Cricket Australia (CA) is now rooted in High-Performance Science and Algorithmic Management.

Predictive Analytics & Biometrics

In Australia, fast bowlers utilise wearable sensors to monitor workload and biomechanical stress.

AI models analyse this data to predict stress fractures before they occur.

Sri Lanka, conversely, continues to cycle through injured pacemen with no predictive oversight.

Virtual Reality (VR) Training

While Australian batters use VR to simulate the trajectories of elite global bowlers, Sri Lankan players remain tethered to traditional net sessions on deteriorating domestic tracks.

Data-Driven Talent Identification:

India’s “transmission system” utilises automated data analysis across thousands of domestic matches to identify players who thrive under specific pressure indices.

In Sri Lanka, 85 percent of national talent still originates from just four districts—a statistical failure in talent scouting and geographic expansion.

Infrastructure vs. Intellect:

A Misallocation of Capital

Sri Lanka Cricket (SLC) boasts massive reserves, yet its investment strategy is fundamentally flawed.

Capital is funneled into “bricks and mortar”—grand stadiums and administrative buildings—rather than the human capital of the sport.

We build colosseums but fail to train the gladiators.

The domestic structure remains a “spin trap.”

By producing “rank turners” to suit club politics, we have effectively de-skilled our batters against elite pace and rendered our spinners ineffective on the flat, true wickets required for international success.

The Leadership Deficit:

A Failure of Succession Planning

The crisis of leadership post-Sangakkara and Mahela is a byproduct of poor “Succession Science.”

Australia maintains a “Culture of Continuity,” backing leadership even through lean periods to ensure stability.

India employs a rigid “Succession Roadmap,” ensuring the next generation is integrated into the system long before the veterans depart.

In contrast, SLC operates on a “carousel of convenience,” changing captains and coaches to distract from administrative failures.

This lack of imaginative management stems from a low literacy in modern Sports Governance.

From a philosophical perspective, our established cricketing traditions have failed to absorb the antithesis of the modern, hyper-professionalized global game.

As a result, a truly modern Sri Lankan brand of cricket has failed to materialise.

Instead, we are trapped in what is called a “Static Synthesis,” where the administration clings to the glories of 1996 and 2014 as a shield against the necessity of change.

This is not a transition; it is a refusal to evolve

We are witnessing the alienation of the sport from its people, where the “Master” (the administration) has become detached from the “Slave” (the grassroots talent and the fans).

The Verdict:

A National Emergency

The “cancer” in Sri Lankan cricket is a trifecta of political interference, irrational management, and a refusal to embrace the Fourth Industrial Revolution (AI, VR, and Big Data).

As someone who contributed to the formation of the Sri Lankan Professional Cricketers’ Association, I see the current trajectory as a betrayal of the players’ potential and the nation’s heritage.

Sri Lanka Cricket does not need another “review committee” or a new coach to act as a human shield for the board.

It needs a “Bitter Pill”—an aggressive, independent restructuring that prioritises scientific professionalisation over cronyism.

Without this, our cricket will remain at the bottom of the well, looking up at a world that has moved light-years ahead.

Shiral Lakthilaka

LLB, LLM/MA

Attorney-at-Law

Former Advisor to H.E. the President of Sri Lanka

Former Member of the Western Provincial Council

Executive Committee member of the Asian Social Democratic Political Parities

Opinion

Unable to forget the dead

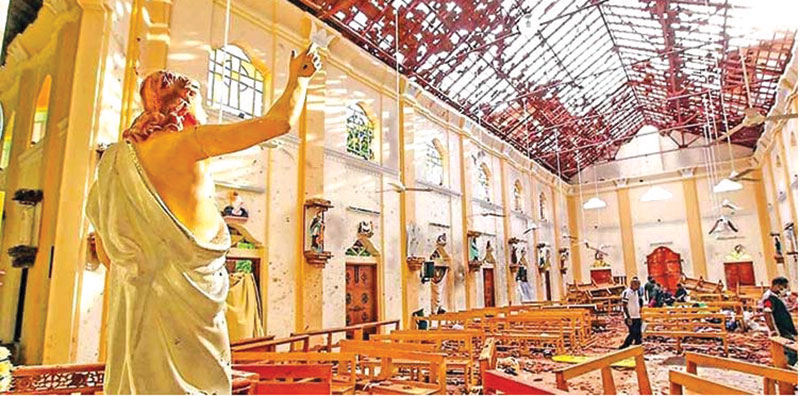

The present government was elected on a commitment to prioritise truth, justice, and accountability to which it is being held by the Catholic Church in particular. This may account for the renewed momentum in investigations into the 2019 Easter Sunday bombings which was one of the gravest acts of violence in Sri Lanka’s recent history. A story on the recent developments in the Easter Sunday bombing investigation refers to a father whose six year old daughter died in the explosions that killed 279 people. The news report quotes him saying, “If she were alive today, she would be 13. You cannot suppress the truth for long. Now it’s starting to come out. We want the full truth and justice. Our children did not die in vain.” https://www.ucanews.com/news/sri-lanka-arrests-ex-intelligence-chief-over-2019-easter-bombings/112031 His words capture the ache of continuing grief and the stubborn refusal to let memory fade into oblivion.

The desire for justice, especially for loved ones killed by the actions or omissions of others, is universal. It is seen in the mothers of the North, in Jaffna and other towns, who have sat by the roadside year after year asking what happened to their children who disappeared in 2009 when the war ended or even earlier as when 158 people were taken from the temporary refugee camp in Eastern University in Vantharumoolai, Batticaloa, on September 5, 1990 never to be seen again. The reality, however, is that the suffering of individuals is easily submerged in the larger schemes of power. Governments are concerned about retaining political power, security forces close ranks, and societies are encouraged to forget in the name of stability, economic recovery, or national pride.

In Sri Lanka that forgetting has not taken place. Due to the sustained efforts of the Catholic Church and the families of the victims, the demand for truth and justice regarding the Easter Sunday attacks has not gone away. It has persisted through indifference, hostility, and at times intimidation. It is perhaps this persistence that has made the arrest of retired Major General Suresh Sallay a significant moment for those who have not forgotten. The arrest of General Sallay, who once headed military intelligence and later the State Intelligence Service, has been controversial. He is widely credited with playing a significant role in dismantling the LTTE’s networks and is regarded by some as one of the country’s most capable intelligence officers.

Persisting Doubts

From the very day of the Easter bombings in April 2019, there has been a doubt that the attacks were too meticulously planned to have been carried out solely by a ragtag group of youth or radicalised men acting on their own. The suspicion of a “grand conspiracy” has existed from the beginning and was voiced even by senior legal officials involved in the investigations. The attacks were claimed to be staged by ISIS, whose leader issued a statement claiming credit for them as part of a global ideological struggle. But this did not answer the central question about why known Muslim extremists were not apprehended when the war with the LTTE had ended many years before and they were no longer needed as a counterforce and why repeated intelligence warnings from India were ignored.

For seven years successive governments failed to move beyond the finding of negligence on the part of those who were in charge of national security. Investigations stalled and key questions remained unanswered. A parliamentary committee questioned whether sections within the intelligence community, supported by some politicians, sought to undermine investigations.

The Supreme Court held several government leaders and senior officials guilty of negligence and dereliction of duty, imposing heavy fines. That judgment established that the state failed its citizens. But negligence is one thing. Deliberate connivance is another. The present government was elected in 2024 on a promise that the truth behind the Easter attacks would be uncovered. President Anura Kumara Dissanayake committed himself publicly to accountability.

As several foreigners including US and UK citizens also lost their lives in the bombings, foreign intelligence agencies from the United States, the United Kingdom and other countries came to Sri Lanka soon after the attacks to conduct their own inquiries. The US has filed charges against three Sri Lankans. So far, international findings have not identified an external mastermind directing the plot from abroad. The focus remains on possible failures or complicity within.

Indeed, by arresting a former intelligence head who was widely credited with playing a significant role in dismantling the LTTE, the government has taken a considerable political risk. Opposition politicians and nationalist voices have framed the arrest as a betrayal of the security forces and an attempt to appease external actors. Others have suggested that it is a diversion from present economic or political challenges.

Beyond Easter

The Catholic Church, which most directly represents the victims of the Easter attacks, has expressed support for the renewed investigations. The involvement of the Church has helped to take the issue beyond the realm of partisan party politics and to one of the search for truth and justice. But this search for the truth cannot be limited to the Easter bombings. It needs to extend beyond this particular bombing, heinous though it was. A state that investigates only one atrocity while ignoring others signals that some lives matter more than others. That is a dangerous message in a country that has been divided along ethnic and religious lines. Truth seeking is not a betrayal of those who fought in difficult circumstances. It is an affirmation that the rule of law applies to all. It strengthens institutions by cleansing them of suspicion. It restores trust between citizens and the state.

Sri Lanka’s modern history is marked by many unresolved crimes. Large scale killings, enforced disappearances, and extrajudicial actions during the period of the ethnic war remain unaccounted for. There were churches and orphanages bombed during the war. There were hundreds taken from camps or who surrendered only to disappear forever. Thousands of families continue to live without answers. The mothers of the disappeared have not gone away.

They sit in the heat and rain because they cannot forget their children and want to know what happened to them. Their persistence mirrors that of the Easter victims’ families. Both ask the same question. Who was responsible and why. For too long Sri Lanka has avoided these questions, arguing that reopening the past would endanger stability and that the path to success is to focus on the future.

But memory and the desire for truth and justice does not die. By prioritising truth and justice as governing principles, the government can begin to restore faith in public institutions. This requires investigating what happened and why accountability was denied. Healing the wounds for Sri Lanka does not lie in forgetting the dead. Justice is not only punitive. It is also restorative. It allows societies to move forward without carrying unspoken burdens.

The Easter Sunday victims, the disappeared of the war years, and all those lost to political violence belong to the same community of Sri Lankan citizens that the government has pledged to treat equally. This calls for a consistent standard of truth. By pursuing the Easter investigation wherever it leads and by reopening and resolving the unresolved crimes of the war years, the government can set the country on a path of redemption.

by Jehan Perera

Opinion

Sri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans

Having watched Sri Lanka play in multiple World Cups (both formats) in six countries over the past 15 years, I regret that the worst facilities for fans are in the ongoing edition in Sri Lanka. I’m in my mid 60s and over many decades have watched our team play in every international cricket venue in Sri Lanka and several abroad. Even in developing countries such as in the Caribbean and Bangladesh, where I saw us triumph in 2014, there seems to be more concern for ordinary spectators and their basic expectations.

On this occasion, I travelled from the other side of the world and had to plan ahead. In the past editions, I recall tickets going on sale well ahead, but on this occasion, only a couple of months for some games and a couple of weeks for others. Even then, only low priced categories were released initially and I snapped them up, only to find better seats released a few days later. When I tried to buy those, I was told by the system that the maximum ticket quota is exceeded. I had to ask a friend to buy the tickets for me and transfer, hence paying multiple times for the same game. Why can’t all tickets be made available transparently to all fans at one time and sold to the 1st comers? Is there some racket in sending tickets “underground” initially to be resold at higher prices or given away free to cronies? I am tempted to believe this as in smaller grounds like P Sara and Galle, I have found in past bilateral tours such as vs England, where tickets are in high demand, the better tickets are never offered for public sale. But at the venue, I find many empty good seats. I understand that hundreds of tickets are given away as compliments to past cricketers families and friends and families of SLC big wigs, who routinely never turn up, depriving the opportunity to fans who are ready to pay for those same seats.

The most agonising part is entering and leaving the grounds which at both Premadasa and Pallekele this year was an absolute nightmare, with high possibilities of stampedes causing serious injuries or worse. Is the ICC not concerned – at least for the sake of avoiding legal liabilities? In past decades I remember long metal barricaded pathways set up a little away from the gates to force fans to queue up for body search, etc. This ensures more orderly entry as Sri Lankans are notorious for queue-jumping. Instead this time round it was a free-for-all for. The next shock is upon entry; there are clearly more people in each stand than the available seats. If you don’t arrive early and grab a seat, you end up standing in the aisles or stairs with an obstructed view and crushed on all sides. I saw some elderly foreign fans walk off half way in disgust. There was a time when in most stands at the R. Premadasa Stadium, a ticket guaranteed a seat. Now, it is not so even in the highest priced Grandstand. Seat numbers have been obliterated. With all the financial stability of the SLC that they claim in media, can’t they afford to repaint the seat numbers and set up some physical queuing pathways? Or is it that they are simply unconcerned about the suffering of ordinary fans? Or do they prefer free seating so that it’s easier to admit favoured individuals free of charge? At a world cup in New Zealand, I observed they had engaged many volunteers, young and old to act as guides/ ushers in and around the stadium. This is a common practice even in Olympics. Apart from trips for multiple board members, their families and other companions, can’t SLC spend a little to send some operational level staff to study and apply the best practices of other member countries to improve things at our local facilities? Moving onto toilets, without exaggeration, Pallekelle had 3 inches of filthy water (maybe urine) on the men’s toilet floor to wade through. In Sri Lanka, it is essential to have the constant presence of several janitors to ensure clean toilets. There wasn’t even one in sight. At the previous edition of this tournament in St. Lucia, West Indies, a small island where Sri Lanka played, I found impeccably clean toilets at the Gros Islet grounds.

Food and beverages is the next bone of contention. Quality and range offered was pathetic compared to the past in Sri Lanka and certainly compared to world cup venues elsewhere. Only plain instant noodle, hot dogs and some Chinese Rolls were generally available and some of the vendor stalls were unbranded, causing doubt in the minds of about the origin and quality of the offerings. Beer was the next scam, at Premadasa only Corona R. 2000 per cup and Budweiser Rs, 1500 were on offer, both unknown brands to most Sri Lankans. Budweiser also ran out early in the match, leaving a Hobson’s choice for fans. Apparently, this was a global sponsorship deal, but strangely at Pallekele, there was a small, unbranded shed in a corner selling Beer (presumably local) at Rs. 500. Was this something underhand? SLC Office bearers boast of their good relationships and having influence at the top levels within ICC. They also sit on their Boards and committees. Can’t they influence better deals on offerings and prices appropriate to local crowds? Finally, at the end of many hours of suffering, we come to the chaotic exit with everybody pouring out into narrow highly populated streets around the Premadasa stadium. With all the millions they are reportedly raking in, can’t SLC attempt to collaborate with the local authorities and acquire some of the surrounding lands, offering the residents attractive deals. Sri Lanka already has a very high number of stadia per capita. Building more and more may be lucrative for some, but investing in improving say three select existing venues to international standards in different parts of the country is the need of the hour. Once I took a flight via Mattala to watch Sri Lanka play at the Sooriyawewa stadium. Built in the middle of nowhere, with no surrounding infrastructure, it fell into total neglect just a few years after it was opened. When thousands of spectators attempt to find their way home at once, it can be anticipated that all modes of public transport including Uber and Pickme get overwhelmed. I had to walk about three kilometres and try repeatedly for almost one hour to secure a ride. After watching Sri Lanka play a world cup match at Sydney Cricket Ground, (capacity 50,000) we were able to calmly walk about 15 minutes to a long line of parked busses which took us painlessly to different points of the city. At the Oval, London, three underground tube stations are within 15 m walking distance and extra trains are deployed to handle the load after matches. Are SLC officers too busy to engage in some discussion with Public and Private sector transportation providers to make some special arrangement for the weary cricket fans?

I bought tickets to watch Sri Lanka play Pakistan in their final game in this tournament, but decided that the hardship and risks of bodily injury to be endured to support our team was not worthwhile at my age. Since that triumphant day in Dhaka in 2014, not only the standard of our Cricket but the facilities and basic comforts expected by ordinary fans have sadly declined drastically.

Sujiva Dewaraja

sujiva.dewaraja@gmail.com

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoAn innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoBuilding on Sand: The Indian market trap

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoRatmalana Airport: The Truth, The Whole Truth, And Nothing But The Truth

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoFuture must be won

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoDialog partners with Xiaomi to introduce Redmi Note 15 5G Series in Sri Lanka

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoIRCSL transforms Sri Lanka’s insurance industry with first-ever Centralized Insurance Data Repository

-

Opinion1 day ago

Opinion1 day agoSri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans