Features

Dinner with daddy: The Motwani dinner table with Kewal, Clara and two daughters

Excerpted from Chosen Ground: The Clara Motwani Saga by Goolbai Gunasekera

One thing I can say about life with my parents is that it was never dull. One parent was a school Principal and the other a Professor, and their united efforts ensured that every shining moment of the day was gainfully employed by their two daughters in learning something. This fact alone made for activity, if not for thrills or excitement.Father had a thing about dinner time conversation.

“Food digests better when we talk of soothing subjects,” he would decree, launching into a debate with Mother about the state of America’s foreign affairs. Mother, being American, and having lived out of the USA from the time of her marriage, was always up to date on what American Presidents were doing. America was the ultimate to her in just about everything, and it was a constant joy to her irreverent family to needle her on the subject whenever possible. She had a low tolerance for criticism of her motherland.

Su and I took sides indiscriminately, and a lively evening was had by all. I don’t know what all this argument did to our digestions, but obviously we flourished. Eventually my sister and I privately decided that the time had come to infuse dinner time chats with topics more to our liking. Accordingly, one night, Su led off.

“I saw a cute boy at the Barnes Place junction today,” she said brightly.

Our parents looked at her blankly. It hadn’t occurred to them that we’d ever noticed such unlikely beings as boys. We were aged thirteen and sixteen respectively, but such were the norms of the times in which we were raised.

Father slapped the table.

“Not of general interest,” he roared. “Now if Su had seen a comet passing overhead — that would be of general interest.”

“Honestly, Daddy,” I said, backing up my sibling, “our dinner conversations are so literary. Why can’t we relax?”

“I’m relaxed,” boomed Father. “Aren’t you relaxed?” he asked Mother across the table. “And what’s your problem in relaxing?”

This last was to me. Father had just read the latest Time on the Vietnam war, and was itching to get going on the subject.

“What would you two like to talk about?” Mother asked diplomatically.

Father looked frustrated, and began to fidget. Now, I’d reached the age of discretion, and hadn’t the slightest intention of revealing to my parents that Dearly Beloved (then Dearly to be Beloved) and I were having what my friends grandly termed an ‘affaire’, but which in reality was just a series of romantic phone calls usually made when everyone was out of the house. I simply smiled and let my sister carry on. She did.

“I want to know,” demanded Su, forthright to the point of lunacy, “if that cute boy I mentioned earlier can come and visit me at home. To chat about books and things,” she added hastily, seeing Father’s face begin to darken.

Mother and I watched apprehensively as his whole body seemed to swell with indignation. Mixing of the sexes was not yet allowed in the Sri Lanka of that time — and even less in sleepy Arazi, his home town, from where he had drawn his ideas on boy/girl relationships.

“Are you actually telling me you have spoken to this young ….” he paused, searching for suitable words, “this young despoiler of innocent girls, this depraved Romeo, this unethical whippersnapper, this……He was well launched.Su was not easily intimidated.

“What are you carrying on like that for?” she asked in honest bewilderment. “All my friends talk to boys at the Barnes Place corner. They cycle with us to school and then they go on to Royal … and stop kicking me, ” she added impatiently, to me.

It will be remembered that, unlike me, Su was a Bridgeteen. Following Mother’s educational theories that sisters should not attend the same school, we had been separated — though, frankly, I feel Mother might have been more concerned for the well-being of the schools rather than for the welfare of her two daughters. The vision of Su and her friends cycling up to the gates of St Bridget’s Convent in convoy, with the young stars of Royal College in attendance, quite shattered my parents.

“It’s boarding school for you, Miss,” Father roared at an indignant Su. “And don’t think I don’t mean it.”

At this point he recalled last month’s telephone bill and gave me a suspicious glare, to which I returned a perfectly bland look.

Following this incident, our parents paid Reverend Mother Superior of St. Bridget’s a visit, and if Father had had his way, one of the nuns would have been permanently stationed at an upstairs window with a telescope trained on all roads leading to the school, to ensure the future and continuing purity of the Convent’s teenage cyclists. Hearing of this exchange betwixt authority and her parents, Su groaned.

“Good grief,” she lamented. “The nuns are sleuths and bloodhounds at the best of times. They’ve got eyes at the back of their heads.”

Actually things did not turn out half as badly as she feared. One of the nuns was an American, like Mother, and she did not view the whole episode with undue alarm. She wigged Su in school.

“Enjoyed your ride to school today, my dear?” she would ask Su, when she passed in the corridor. Su would smile weakly.

“Honestly,” she fumed to me, “to think a damn dinner conversation would lead to all this. Father can carry on about world affairs all he likes. I’m not going to say one word at meal times to anyone about anything.”

Father ignored her sulks, and Su kept her vow of silence for a week. Our sire carried on his soliloquy on topics of his choosing, but the salt of his conversational meal was lacking. Without the thrust and parry of my sister’s witty questions and cheeky opinions, he found dinner time pretty damn dull. Finally, he addressed himself gruffly to his younger offspring:

“Come now, Miss Grumpy, I’ve forgiven you.”

Truth to tell, Su, who loved talking, was finding her self-imposed silence unexpectedly hard to cope with. Matters returned to normal, but Su being Su, this happy state did not long continue.

One month to the day after the previous disaster she upset the dinner equilibrium all over again.

“I want to know,” she demanded of Father, “when I can learn to ballroom dance properly.”

Mother and I froze in our seats, and watched Father turn that familiar shade of puce. He opened and shut his mouth several times.

“At thirteen?” he said in a strangled voice. It was more a statement than a question.

“At thirteen?” he bellowed again, finding his usual tonal timbre, and she wants to dance with other equally silly 13-year-olds, I suppose?”

I sat looking demure, my halo shining brightly in contrast with what I thought was Su’s less than scintillating performance. But life is so unfair. A fortnight later, my cheeky younger sister joined Frank Harrison’s School of Dancing, and went on to win the odd medal here and there too. I was speechlessly envious.

“The thing is,” she told me, “the thing is to ask Father for the impossible. Then he settles for what you really want.”

Considering Father’s views on friendship between teens of opposite sexes, he was surprisingly non-vocal when it came to marriage. Both he and Mother realized the impracticability of arranging marriages for us in India.But one story needs be told.

One day Father received an agitated letter from a wealthy Sindhi merchant who had been his playmate in the village of Arazi. The merchant’s only son (the apple of his eye) was now practicing medicine in the USA, and was refusing to marry a Sindhi girl, claiming that he was too ‘westernized’ to settle down in India with an Indian wife. He wanted to marry an American colleague – also a doctor.

“Just think, Kewal, only my foolish son would think that an American would like India,” lamented the merchant, quite forgetting that Kewal’s own wife felt quite at home in Asia.

It transpired that the wayward son would consider marrying an Indian girl if she were educated and ‘westernized’. His distraught father suddenly remembered that his boyhood friend had an American wife and also two half-American daughters. He assumed that at least one daughter must be of marriageable age, hence the letter to Father asking permission for his son to meet one of them.

Father summoned me. His success with Mother over his attempts at arranging marriages for us had so far been minimal. She had washed her hands of the whole affair, thinking Father must really be out of his mind to be doing something so uncharacteristic. Father just could not get away from Arazi influences at times. In any case, she had a pretty shrewd idea how I would react.

Clearing his throat and looking at a point over my head, Father said gruffly:

“Er, would you like to meet a nice young man when you go to University in Bombay?”

I could hardly believe my ears.

“What?”

“A doctor is looking for a wife.”

Truly, Father’s personal persuasive skills were nil. “So?”

“Well … er … would you like to meet him?”

The chance of paying Father back was too good to miss. “Daddy! Are you arranging for me to speak to a BOY?”

“Well, he is a mature and well-qualified individual. Not the sort I see hanging around near post-boxes, that your sister seems to find so exciting.”

“Daddy, are you SURE? He might have only one thing on his mind.”

(One of Father’s pet phrases at this time was: “Young men have only one thing on their minds, and that one thing is not repeatable.”)

Father knew he had to accept the wigging. He accepted our pretended shock with good grace, and told me it was entirely up to me.

In point of fact I did meet the young man in question. He took me out to dinner when I was at university in Bombay, but both of us had other romances going and marriage between us was not an option. However he has always been a convenient peg on which to hang a winning argument with my husband. During any disagreement I can always say:

“And to think I gave up a doctor for you!”

Father wrote to his friend. According to Mother, he gave his usual excuse.

“Who am I, a mere father, to know what goes on in the heads of women. Let your son marry his American. He will probably be very happy. After all – I am.”

Riot over the diet

Father’s long lecture tours distanced him from his growing family for much of the time. He was thus spared the sight and company of squealing babies, which in his eyes was all to the good. Father never learnt to carry an infant. “Squirming little creatures,” was his comment on all new borns.

Not given to panegyrics, he viewed his two daughters with a judicial eye. He seemed to regard any successes of ours as accidental and unexpected. Fortunately, Mother was the opposite. My sister Su and I grew up in an alien land, but not once did we feel anything but totally Sri Lankan. For this we had our parents to thank, for we were brought up as Sri Lankans first, and Asian/Americans as an afterthought.

Our school friends had parents who had fallen into the traditional roles of courtship and marriage. Our own parents, on the other hand, had fallen into a quite unique category. We never tired of hearing the tale. “So tell us, Daddy,” Su would say, “Tell us the story of how you proposed?”

Father loved the narrative. “What do you mean, ‘propose’?” he would ask. “Your Mother saw this superbly romantic-looking Indian and I hadn’t a chance in hell. I was at the altar before I knew it.”

Mother would sigh resignedly. She knew, and we both knew too, that the reality had been very different.

Father was 28 and Mother just 18 when they got engaged. At 19 Mother was married, and half way through her degree in Languages and Music at the University of Iowa. Just after their marriage, Father transferred from Yale in order to be near her. When the financial debacle of the Wall Street crash wiped out Father’s American bank account, it meant that our parents could not afford to live together on campus since married quarters were expensive.

Accordingly they simply pretended they were single. When Mother was awarded her degree, Father insisted that she do a Master’s in Education. “The British will go,” he predicted, “and India’s schools and colleges will need qualified Principals.”

Mother thereupon enrolled in Professor Ensign’s class and began her thesis. Professor Ensign was an avuncular type of person, and had given Father quite a lot of added correction work by way of helping him earn extra income. One morning, he called Father aside. “Kewal,” he began, “I have a young girl from Kentucky in my class who is interested in the East. I think you should meet her and tell her about India.”

Father agreed, of course, and found himself being introduced to Mother. They shook hands gravely, trying not to meet each other’s eyes. To the end of his days, Professor Ensign thought he had played Cupid. Father never enlightened him, and the story of his matchmaking success enlivened the good Professor’s dinner table for many moons after that.

Mother took me to see Professor Ensign when I was four years old, as she was back in America on furlough. He patted my head, and gave me a photograph of himself with Mother on one side of him and Father on the other. It was a picture I treasured for many years but alas, cannot trace at this moment.

“You wouldn’t be here if not for me,” he is supposed to have said to me. Mother smiled her gentle smile. “Very true,” she said, telling one of the few untruths she ever uttered.

One wonders how a bond was forged between a youngAmerican girl and an already mature Indian Doctor of Sociology. What similarities existed that resulted in this unusual yet successful partnership? Su and I would endlessly discuss the matter. Both of us expected to marry in Sri Lanka or India (which we did), and both of us wondered what it would be like if we fell in love with an American.

“You won’t have the chance,” Father told us grimly once, when Su had been foolish enough to voice her views on matrimony. “Perish the thought. You’ll marry here, and like it.”

So what was the glue that held the bond between our parents firm? Firstly, both were Theosophists. My American grandmother was so much into Theosophy that she even influenced Mother to become a vegetarian at 17. Father had been a vegetarian from birth and through Jamshed was an ardent Theosophist himself, so it does seem as though similar food habits and similar religious beliefs formed that first strong link between them. Secondly, they were both highly educated. A third factor was the difference in age between them: Father did not find it difficult to mould his young wife into his ways of thinking.

He found Su and me, his two daughters, far more of a challenge than he liked. “Where has your Mother’s gentleness gone?” he would demand, glaring at Su’s rebellious face. On principle Su objected to everything. “I’m going to eat meat the minute I marry,” she would declare. Father would blench.

“And I’ll drink, too,” she would add. He would go even paler.

“We’ve begotten a changeling,” Father would tell Mother, who would smile and tell him to bear in mind that adolescence was generally a trying time. “If those two young ingrates want to make graveyards of their stomachs, who am I, a mere Father, to stop them?” he would say plaintively, hoping Su would overhear him. “And if liquor addles their brains, it doesn’t matter. They are addled already. Curdled would be a better description,” he would add.

Father’s aversion to meat and liquor certainly led us into some strange situations. Travelling together in America had Su and me cringing in our seats at restaurants. “The steak is excellent, sir,” the waiter would say, handing Father the menu. Father felt called upon to inform the entire restaurant, of his dietary preferences.

“Not a piece of meat has ever passed my lips,” he would declare in ringing tones. “And I don’t intend to start now.”

“Perhaps a nice Dover sole, then?” the waiter would say soothingly. Father’s voice would rise several notes. “And what, pray, is the difference?” he would ask the unfortunate waiter. “They are both flesh of living creatures, are they not? Nasty bloody business, all this meat guzzling.”

Diners at other tables began to lose their appetites. Father was in full spate. “Just order, dear,” Mother would say tactfully and, truth to tell, the manager of the restaurant was by now ready to give us all a free meal just to get Father out of there. Everyone settled for omelettes and salad. Fortunately no one had yet heard of the cholesterol scare, and we must have eaten enough eggs to start a poultry farm upon our return home. Father did not think eggs violated any Brahmin laws of ethics or dietetics.

His attitude to liquor was even worse. He had dinner one night with Mr. and Mrs. Argus Tressider, American diplomats in Colombo in the 1950s. A week later, Nancy Tressider met Father again and he complimented her on her dessert.

“Oh, you liked my brandy souffle, did you?” she asked innocently, not realizing that she was virtually hitting Father in the solar plexus. He went pale, and his stomach churned. He collected Mother, and hightailed it out of there so fast she had hardly any time to make her excuses to her hostess. He went home and was sick for twenty-four hours.

“I’m poisoned, poisoned,” he groaned hollowly every few minutes. “My entire system has been polluted.” He went on a water diet of detoxification. He was a psychological mess. Nancy rang up the next day to find out how Father was getting along after his hasty exit the previous night. Mother told her the truth. “But Clara, my dear,” Nancy said, “I only used brandy flavouring for the pudding.”

Father faced our gales of glee with fortitude. He admitted shamefacedly that it was a case of mind over matter, but when the day eventually came that Su married an officer of the Indian Army and did take the occasional glass of wine, Father was genuinely upset. “Your pure bodies,” he would lament. “What a great, great pity.” I never had the courage to admit that I did likewise. “Poppycock,” Su would mutter.

But now that I am a grandmother myself, and face dietary and health problems as do we all, I wonder: did Father have a point?

Features

The State of the Union and the Spectacle of Trump

President Donald J. Trump, as the American President often calls himself, is a global spectacle. And so are his tariffs. On Friday, February 20, the US Supreme Court led by Chief Justice John Roberts and a 6-3 majority, struck down the most ballyhooed tariff scheme of all times. Upholding the earlier decisions of the lower federal courts, the Supreme Court held that Trump’s use of ‘emergency powers’ to impose the so called Liberation Day tariffs on 2 April 2025, is not legal. The Liberation Day tariffs, which were comically announced on a poster board at the White House Rose Garden, is a system of reciprocal tariffs applied to every country that exported goods and services to America. The court ruling has pulled off the legal fig leaf with which Trump had justified his universal tariff scheme.

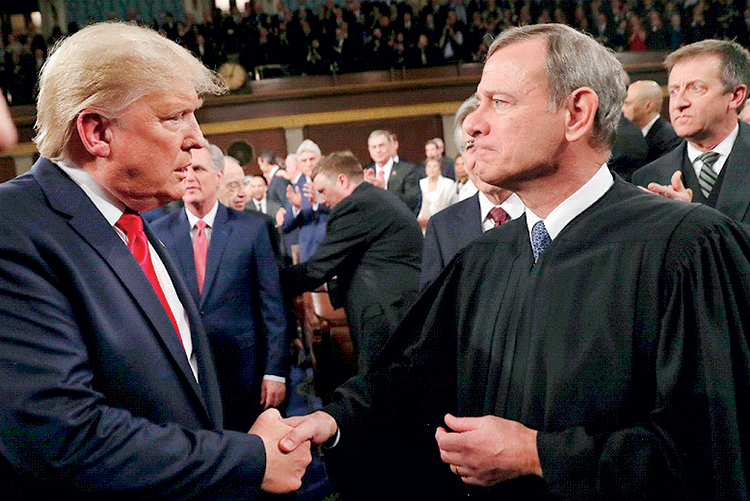

Trump was livid after the ruling on Friday and invectively insulted the six judges who ruled against Trump’s tariffs. There was nothing personal about it, but for Trump, the ever petulant man-boy, there isn’t anything that is not personal. On Tuesday night in Washington, Trump delivered his first State of the Union address of his second presidency. The Chief Justice, who once called the State of the Union, “a political pep rally,” attended the pomp and exchanged a grim handshake with the President.

Tuesday’s State of the Union was the longest speech ever in what is a long standing American tradition that is also a constitutional requirement. The Trump showmanship was in full display for the millions of Americans who watched him and millions of others in the rest of world, especially mandarins of foreign governments, who were waiting to parse his words to detect any sign for his next move on tariffs or his next move in Iran. There was nothing much to parse, however, only theatre for Trump’s Republican followers and taunts for opposing Democrats. He was in his usual elements as the Divider in Chief. There was truly little on offer for overseas viewers.

On tariffs, he is bulldozing ahead, he boasted, notwithstanding the Supreme Court ruling last Friday. But the short lived days of unchecked executive tariff powers are over even though Trump wouldn’t let go of his obsessive illusions. On the Middle East, Trump praised himself for getting the release of Israeli hostages, dead or alive, out of Gaza, but had no word for the Palestinians who are still being battered on that wretched strip of land. On Ukraine, he bemoaned the continuing killings in their thousands every month but had no concept or plan for ending the war while insisting that it would not have started if he were president four years ago.

He gave no indication of what he might do in Iran. He prefers diplomacy, he said, but it would be the most costly diplomatic solution given the scale of deployment of America’s fighting assets in the region under his orders. In Trump’s mind, this could be one way of paying for a Nobel Prize for peace. More seriously, Trump is also caught in the horns of a dilemma of his own making. He wanted an external diversion from his growing domestic distractions. If he were thinking using Iran as a diversion, he also cannot not ignore the warnings from his own military professionals that going into Iran would not be a walk in the park like taking over Venezuela. His state of mind may explain his reticence on Iran in the State of the Union speech.

Even on the domestic front, there was hardly anything of substance or any new idea. One lone new idea Trump touted is about asking AI businesses to develop their own energy sources for their data centres without tapping into existing grids, raising demand and causing high prices and supply shortages. That was a political announcement to quell the rising consumer alarms, especially in states such as Michigan where energy guzzling data centres are becoming hot button issue for the midterm Congress and Senate elections in November. Trump can see the writing on the wall and used much of his speech to enthuse his base and use patriotism to persuade the others.

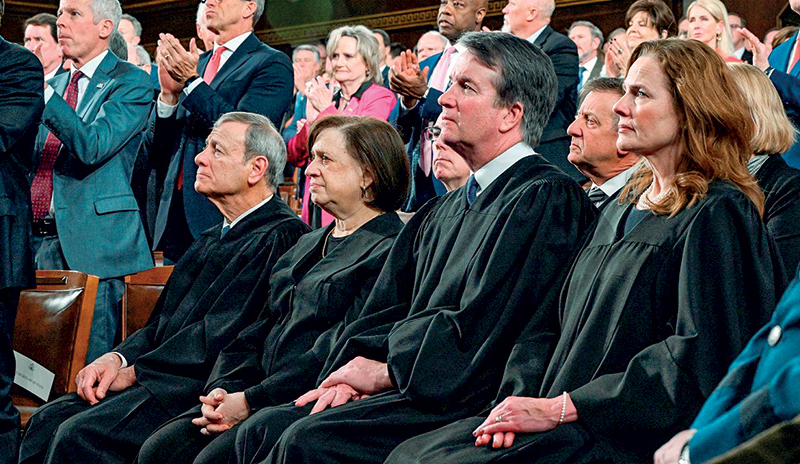

Political Pep Rally: Chief Justice John G. Roberts sits stoically with Justices Elena Kagan, Bret Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett, as Republicans are on their feet applauding.

Although a new idea, asking AI forces to produce their own energy comes against a background of a year-long assault on established programs for expanding renewable energy sources. Fortunately, the courts have nullified Trump’s executive orders stopping renewable energy programs. But there is no indication if the AI sector will be asked to use renewable energy sources or revert to the polluting sources of coal or oil. Nor is it clear if AI will be asked to generate surplus energy to add to the community supply or limit itself to feeding its own needs. As with all of Trump’s initiatives the devil is in the details and is left to be figured out later.

The Supreme Court Ruling

The backdrop to Tuesday’s State of the Union had been rendered by Friday’s Supreme Court ruling. Chief Justice Roberts who wrote the majority ruling was both unassuming and assertive in his conclusion: “We claim no special competence in matters of economics or foreign affairs. We claim only, as we must, the limited role assigned to us by Article III of the Constitution. Fulfilling that role, we hold that IEEPA (International Emergency Economic Powers Act) does not authorize the President to impose tariffs.”

IEEPA is a 1977 federal legislation that was enacted during the Carter presidency, to both clarify and restrict presidential powers to act during national emergency situations. The immediate context for the restrictive element was the experience of the Nixon presidency. One of the implied restrictions in IEEPA is in regard to tariffs which are not specifically mentioned in the legislation. On the other hand, Article 1, Section 8 of the US Constitution establishes taxes and tariffs as an exclusively legislative function whether they are imposed within the country or implemented to regulate trade and commerce with other countries. In his first term, Trump tried to impose tariffs on imports through the Congress but was rebuffed even by Republicans. In the second term, he took the IEEA route, bypassing Congress and expecting the conservative majority in the Supreme Court to bail him out of legal challenges. The Court said, No. Thus far, but no farther.

The main thrust of the ruling is that it marks a victory for the separation of powers against a president’s executive overreach. Three of the Court’s conservative judges (CJ Roberts, Neil Gorsuch, and Amy Coney Barrett) joined the three liberal judges (all women – Sonia Sotomayor, Elana Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson) to chart a majority ruling against the president’s tariffs. The three dissenters were Brett Kavanugh, who wrote the dissenting opinion, Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito. Justices Gorsuch, Kavanaugh and Barrett were appointed by Trump. Trump took out Gorsuch and Barrett for special treatment after their majority ruling, while heaping praise on Kavanaugh who ruled in favour of the tariffs. Barrett and Kavanaugh attended the State of the Union along with Roberts and Kagan, while the other five stayed away from the pep rally (see picture).

The Economics of the Ruling

In what was a splintered ruling, different judges split legal hairs between themselves while claiming no special competence in economics and ruling on a matter that was all about trade and economics. Yale university’s Stephen Roach has provided an insightful commentary on the economics of the court ruling, while “claiming no special competence in legal matters.” Roach takes out every one of Trump’s pseudo-arguments supporting tariffs and provides an economist’s take on the matter.

First, he debunks Trump’s claim that trade deficits are an American emergency. The real emergency, Roach notes, is the low level of American savings, falling to 0.2% of the national income in 2025, even as trade deficit in goods reached a new record $1.2 trillion. America’s need for foreign capital to compensate for its low savings, and its thirst for cheap imported goods keep the balance of payments and trade deficits at high levels.

Second, by imposing tariffs Trump is not helping but burdening US consumers. The Americans are the ones who are paying tariffs contrary to Trump’s own false beliefs and claims that foreign countries are paying them. 90% of the tariffs have been paid by American consumers, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Small businesses have paid the rest. Foreign countries pay nothing but they have been making deals with Trump to keep their exports flowing.

According to published statistics, the average U.S. applied tariff rate increased from 1.6% before Trump’s tariff’s to 17%, the highest level since World War II. The removal of reciprocal tariffs after the ruling would have lowered it to 9.1%, but it will rise to 13% after Trump’s 15% tariffs. The registered tariff revenue is about $175 billion, 0.6% of U.S. gross domestic product. The tariff monies collected are legally refundable. The Supreme Court did not get into the modalities for repayment and there would be multiple lawsuits before the lower courts if the Administration does not set up a refunding mechanism.

Lastly, in railing against globalization and the loss of American industries, Trump is cutting off America’s traditional allies and trading partners in Europe, Canada and Mexico who account for 54% of all US trade flows in manufactured goods. Cutting them off has only led these countries to look for other alternatives, especially China and India. All of this is not helping the US or its trade deficit. The American manufacturers (except for sectoral beneficiaries in steel, aluminum and auto industries), workers and consumers are paying the price for Trump’s economic idiosyncrasies. As Roach notes, the Court stayed away from the economic considerations, but by declaring Trump’s IEEPA tariffs unconstitutional, the Court has sent an important message to the American people and the rest of the world that “US policies may not be personalized by the whims of a vindictive and uninformed wannabe autocrat.”

by Rajan Philips

Features

The Victor Melder odyssey: from engine driver CGR to Melbourne library founder

He celebrated his 90th birthday recently, never returned to his homeland because he’s a bad traveler

(Continued from last week)

THE GARRAT LOCOS, were monstrous machines that were able to haul trains on the incline, that normally two locos did. Whilst a normal loco hauled five carriages on its own, a Garrat loco could haul nine. When passenger traffic warranted it and trains had over nine carriages or had a large number of freight wagons, then a Garret loco hauled the train assisted by a loco from behind.

When a train was worked by two normal locos (one pulling, the other pushing) and they reached the summit level at Pattipola (in either direction), the loco pushing (piloting) would travel around to the front the train and be coupled in front of the loco already in front and the two locos took the train down the incline. With a Garraat loco this could not be done as the bridges could not take the combined weight. The pilot loco therefore ran down single, following THE TRAIN.

My father was stationed at Nawalapitiya as a senior driver at the time, and it wasn’t a picnic working with him. He believed in the practical side of things and always had the apprentices carrying out some extra duties or the other to acquaint themselves with the loco. I had more than my fair share.

After the four months upcountry, we were back at Dematagoda on the K. V. steam locos. From the sublime to the ridiculous, I would say after the Garret locos upcountry. Here the work was much easier and at a slower pace, as the trains did not run at speed like their mainline counterparts. The last two months of the third year saw us on the two types of diesel locos on the K.V. line, the Hunslett and Krupp diesels, which worked the passenger trains. For once this was a ‘cushy, sit-down’ job, doing nothing exciting, but keeping a sharp lookout and exchanging tablets on the run. The third year had come to an end and ‘the light at the end of tunnel was getting closer’.

The fourth year saw us all at the Diesel loco shed at Maradana, which was cheek by jowl with the Maradana railway station. The first three months we worked with the diesel mechanical fitters and the following three months with the electrical fitters. Heavy emphasis was placed on a working knowledge of the electrical circuits of the different diesel locos in service, to ensure the drivers were able to attend to electrical faults en-route and bring the train home. This was again a period of lectures and demonstrations

We also spent three months at the Ratmalana workshops, where the diesels were stripped down to the core and refitted after major repairs, to ensure we had a look at what went on inside the many closed and sealed working parts. This was again a 7.00am to 4.00pm day job. Back again at the Diesel shed, Maradana, saw us riding as assistants for the next three months on all the diesel locos in service – The Brush Bragnal (M1), General Electrical (M2), Hunslett locos (G2) and Diesel Rail Cars.

After the final written test on Diesel locos, we began our fifth and final year, which was that of shunting engine driver. The first six months were spent at Maligawatte Yard on steam shunting locos and the next three months shunting drivers on the diesel shunting locos at Colombo goods yard. The final three months were spent as assistants on the M1 and M2 locos working all the fast passenger and mail trains.

I was finally appointed Engine Driver Class III on July 6, 1962, as mentioned earlier I lost eight months of my apprenticeship due to being ill and had to make up the time. This appointment was on three years’ probation, on the initial salary of the scale Rs 1,680 – 72 – Rs 2,184, per annum.

Little did the general traveling public realize that they had well trained and qualified engine drivers working their trains to time Victor was stationed in Galle until December 1967, when he resigned from the railway to migrate to Melbourne, Australia to join the rest of his family. He was the last of 11 siblings to leave Ceylon. Their two elder children were born in Galle. Victor and Esther had three more children in Australia. The children, three boys and two girls) were brought up with love and devotion. They have seven grandchildren and two great grandchildren. They meet often as a family.

He worked for the Victorian State Public Service and retired in 1993 after 25 years’ service. At the time of retirement, he worked for the Ministry for Conservation & Environment. He held the position of Project Officer in charge of the Ministry’s Procedural Documents.

He worked part-time for the Victorian Electoral Office and the Australian Electoral Office, covering State and Federal Elections, from 1972 to 2010. From 1972 to 1982 and was a Clerical Officer and then in 1983 was appointed Officer-in-Charge, Lychfield Avenue Polling Booth, Jacana which is my (the writer’s) electorate.

As part of serving the community Victor participated in a number of ways, quite often unremunerated. He worked part-time for the Department of Census & Statistics, and worked as a Census Collector for the Census of 1972, 1976, 1980 and then Group Leader of 16 Collectors in his area for the 1984, 1988, 1992, 1996, 2000, 2004, 2008 and 2012.

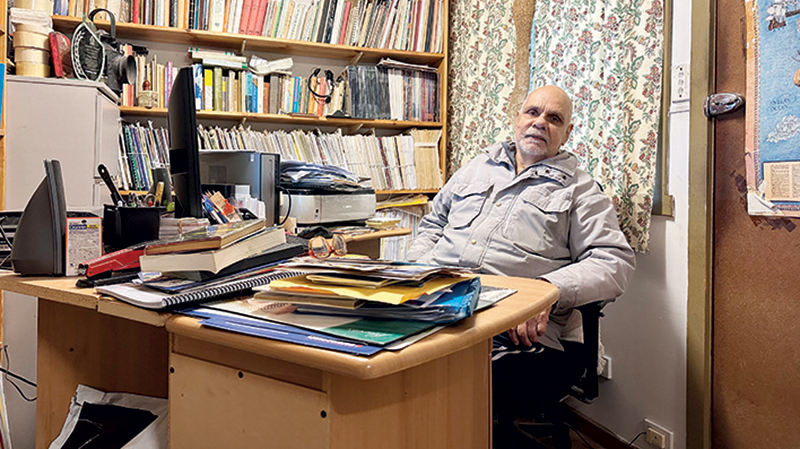

In 1970, Victor began this library, now known as the ‘Victor Melder Sri Lanka Library’, for the purpose of making Sri Lanka better known in Australia. On looking back he has this to say: “Forty-five years later, I can say that it is serving its purpose. In 1993 President Ranasinghe Premadasa of Sri Lanka bestowed on me a national honor – ‘Sri Lanka Ranjana’ for my then 25 years’ service to Sri Lanka in Australia. I feel very privileged to be honored by my motherland, which I feel is the highest accolade one can ever get.”

There were many more accolades over the years:

15.10. 2004, Serendib News, 2004 Business and Community Award.

4.2.2008, Award for Services to the SL Community by The Consulate of Sri Lanka in Victoria (by R. Arambewela)

2024 – SL Consul General’s Award

In 2025 , Victor was one of the ten outstanding Sri Lankans in Australia at the Lankan Fest.

An annual Victor Melder Appreciation award was established to honour an outstanding member by the SriLankan Consulate.

The following appreciation by the late Gamini Dissanayake is very appropriate.

Comment by the late Minister Gamini Dissanayake, in the comment book of the VMSL library.

A man is attached to many things. Attachments though leading to sorrow in the end

are the living reality of life. Amongst these many attachments, the most noble are the attachments to one’s family and to one’s country. You have left Sri Lanka long ago but “she” is within you yet and every nerve and sinew of your body, mind and soul seem to belong there. In your love for the country of your birth you seem to have no racial or religious connotations – you simply love “HER” – the pure, clear, simple, abstract and glowing Sri Lanka of our imagination and vision. You are an example of what all Sri Lankan’s should be. May you live long with your vision and may Sri Lanka evolve to deserve sons like you.

With my best Wishes.

Gamini Dissanayake, Minister from Sri Lanka.

15 February 1987.

The Victor Melder Lecture

The Monash council established the Victor Melder Lecture which is presented every February. It is now an annual event looked forward to by Melbournians. A guest lecturer is carefully chosen each year for this special event.

Victor and his library has featured on many publications such as the Sunday Times in 2008 and LMD International in 2026.

“Although having been a railway man, I am a poor traveler and get travel sickness, hence I have not travelled much. I have never been back to Sri Lanka, never travelled in Australia, not even to Geelong. I am happiest doing what I like best, either at Church or in this library. My younger daughter has finally given up after months of trying to coax, cajole and coerce me into a trip to Sri Lanka to celebrate this (90th) birthday.

I am most fortunate that over the years I have made good friends, some from my school days. It is also a great privilege to grow old in the company of friends — like-minded individuals who have spent their childhood and youth in the same environment as oneself and shared similar life experiences.”

Victor’s love of books started from childhood. Since his young years he has been interested in reading. At St Mary’s College, Nawalapitiya, the library had over 300 books on Greek and Roman history and mythology and he read every one of them.

He read the newspapers daily, which his parents subscribed to, including the ‘Readers Digest’.His mother was an avid fan of Crossword Puzzles and encouraged all the children to follow her, a trait which he continues to this day.

At his workplace in Melbourne, Victor encountered many who asked questions about Ceylon. Often, he could not find an answer to these queries. This was long before the internet existed. He then started getting books on Ceylon/SriLanka and reading them. Very soon his collection expanded and he thought of the Vicor Melder SriLanka Library as source of reference. It is now a vast collection of over 7,000 books, magazines and periodicals.

Another driver of his service to fellow men is his deep Catholic faith in which he follows the footsteps of the Master.

Victor was baptized at St Anthony’s Cathedral, Kandy by Fr Galassi, OSB. Since the age of 10 he have been involved with Church activities both in Sri Lanka and Australia. He remains a devout Catholic and this underlies his spirit of service to fellowmen.

He began as an Altar Server at St Mary’s Church, Nawalapitiya, and continued even in his adult life. In Australia, Esther and Victor have been Parishioners at St Dominic’s Church, Broadmeadows, since 1970.He started as an Adult Server and have been an Altar Server Trainer, Reader and Special Minister He was a member of the ‘Counting Team’ for monies collected at Sunday Masses, for 35 years.

He has actively retired from this work since 2010, but is still ‘on call’, to help when required. To add in his own words

“My Catholic faith has always been important to me, and I can never imagine my having spent a day away from God. Faith is all that matters to Esther too. We attend daily Mass and busy ourselves with many activities in our Parish Church.

For nearly 25 years, we have also been members of a religious order ‘The Community of the Sons & Daughters of God’, it is contemplative and monastic in nature, we are veritable monks in the world. We do no good works, other than show Christ to the world, by our actions. Both Esther and I, after much prayer and discernment have become more deeply involved, taking vows of poverty, obedience and chastity, within the Community. Our spirituality gives us much peace, solace and comfort.”

“This is not my CV for beatification and canonization. My faith is in fact an antidote for overcoming evil, I too struggle like everyone else. I have to exorcise the demons within me by myself. I am a perfect candidate for “being a street angel and home devil” by my constant impatience, lack of tolerance and wanting instant perfection from everyone. “

The above exemplifies the humility of the man who admits to his foibles.

More than 25 years ago The Ceylon Society of Australia was formed in Sydney by a group of Ceylon lovers led by Hugh Karunanayake. Very soon the Melbourne chapter of the organization was formed, and Victor was a crucial part of this. At every Talk, Victor displayed books relevant to the topic. For many years he continued to do so carrying a big box of books and driving a fair distance to the meeting place. Eventually when he could no longer drive his car, he made certain that the books reached the venue through his close friend, Hemal Gurusinghe.

He also was the guest speaker at one of the meetings and he regaled the audience with railway stories.

Victor has dedicated his life on this mission, and we can be proud of his achievements. His vision is to find a permanent home for his library where future generations can use it and continue the service that he commenced. The plea is to get like-minded individuals in the quest to find a suitable and permanent home for the Victor Melder Srilankan Library.

by Dr. Srilal Fernando

Features

Sri Lanka to Host First-Ever World Congress on Snakes in Landmark Scientific Milestone

Sri Lanka is set to make scientific history by hosting the world’s first global conference dedicated entirely to snake research, conservation and public health, with the World Congress on Snakes (WCS) 2026 scheduled to take place from October 1–4 at The Grand Kandyan Hotel in Kandy World Congress on Snakes.

The congress marks a major milestone not only for Sri Lanka’s biodiversity research community but also for global collaboration in herpetology, conservation science and snakebite management.

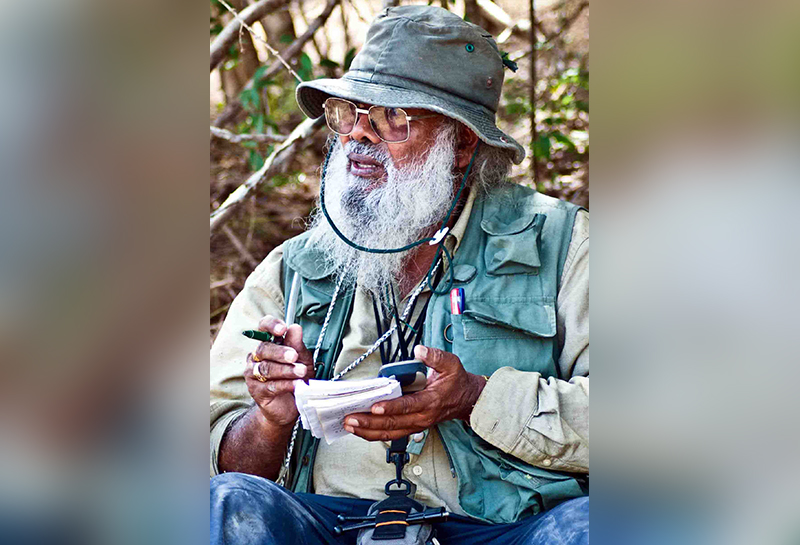

Congress Chairperson Dr. Anslem de Silva described the event as “a long-overdue global scientific platform that recognises the ecological, medical and cultural importance of snakes.”

“This will be the first international congress fully devoted to snakes — from their evolution and taxonomy to venom research and snakebite epidemiology,” Dr. de Silva said. “Sri Lanka, with its exceptional biodiversity and deep ecological relationship with snakes, is a fitting host for such a historic gathering.”

Global Scientific Collaboration

The congress has been established through an international scientific partnership, bringing together leading experts from Sri Lanka, India and Australia. It is expected to attract herpetologists, wildlife conservationists, toxinologists, veterinarians, genomic researchers, policymakers and environmental organisations from around the world.

The International Scientific Committee includes globally respected experts such as Prof. Aaron Bauer, Prof. Rick Shine, Prof. Indraneil Das and several other authorities in reptile research and conservation biology.

Dr. de Silva emphasised that the congress is designed to bridge biodiversity science, medicine and society.

“Our aim is not merely to present academic findings. We want to translate science into practical conservation action, improved public health strategies and informed policy decisions,” he explained.

Addressing a Neglected Public Health Crisis

A key pillar of the congress will be snakebite envenoming — widely recognised as a neglected tropical health problem affecting rural communities across Asia, Africa and Latin America.

“Snakebite is not just a medical issue; it is a socio-economic issue that disproportionately impacts farming communities,” Dr. de Silva noted. “By bringing clinicians, toxinologists and conservation scientists together, we can strengthen prevention strategies, improve treatment protocols and promote community education.”

Scientific sessions will explore venom biochemistry, clinical toxinology, antivenom sustainability and advances in genomic research, alongside broader themes such as ecological behaviour, species classification, conservation biology and environmental governance.

Dr. de Silva stressed that fear-driven persecution of snakes, habitat destruction and illegal wildlife trade continue to threaten snake populations globally.

“Snakes play an essential ecological role, particularly in controlling rodent populations and maintaining agricultural balance,” he said. “Conservation and public safety are not opposing goals — they are interconnected. Scientific understanding is the foundation for coexistence.”

The congress will also examine cultural perceptions of snakes, veterinary care, captive management, digital monitoring technologies and integrated conservation approaches linking biodiversity protection with human wellbeing.

Strategic Importance for Sri Lanka

Hosting the global event in the historic city of Kandy — a UNESCO World Heritage site — is expected to significantly enhance Sri Lanka’s standing as a hub for scientific and environmental collaboration.

Dr. de Silva pointed out that the benefits extend beyond the four-day meeting.

“This congress will open doors for Sri Lankan researchers and students to access world-class expertise, training and international partnerships,” he said. “It will strengthen our national research capacity in biodiversity and environmental health.”

He added that the event would also generate economic activity and position Sri Lanka as a destination for high-level scientific conferences, expanding the country’s international image beyond traditional tourism promotion.

The congress has received support from major international conservation bodies including the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Save the Snakes, Cleveland Metroparks Zoo and the Amphibian and Reptile Research Organization of Sri Lanka (ARROS).

As preparations gather momentum, Dr. de Silva expressed optimism that the World Congress on Snakes 2026 would leave a lasting legacy.

“This is more than a conference,” he said. “It is the beginning of a global movement to promote science-based conservation, improve snakebite management and inspire the next generation of researchers. Sri Lanka is proud to lead that conversation.”

By Ifham Nizam

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoLOVEABLE BUT LETHAL: When four-legged stars remind us of a silent killer

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoBathiya & Santhush make a strategic bet on Colombo

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoSeeing is believing – the silent scale behind SriLankan’s ground operation

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoProtection of Occupants Bill: Good, Bad and Ugly

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoPrime Minister Attends the 40th Anniversary of the Sri Lanka Nippon Educational and Cultural Centre

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoCoal ash surge at N’cholai power plant raises fresh environmental concerns

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoHuawei unveils Top 10 Smart PV & ESS Trends for 2026

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?