Features

Will govt. reveal its plan for developing Ratmalana Airport?

In 1934 the State Council of Ceylon decided that an airport with easy access to Colombo was a necessity and declared that Ratmalana was the best site available. Accordingly, an air field was built and the first landing took place on 27 November 1935. This was Ceylon’s first designated Airfield. With the advent of WWII, the airport expanded and a runway was also built. The Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm used it.

To assist aircraft landing in bad weather and resulting bad visibility, a transmitter was built at Thalangama to generate a Radio Signal Beam directed along the extended centre line of the runway at Ratmalana. If the aircraft was tracking the correct path, the pilots would hear a continuous tone on their headsets. However if they were left of the desired track, the pilots would hear a letter ‘A’ in Morse code (dit dah) or if right, a letter ‘N’ which was a (dah dit) in Morse code. The objective was to hear a continuous signal in the ears, which guided them towards Ratmalana. The descent to lower altitude was at the pilot’s discretion.

As time went by, there was a low frequency, Non-Directional Radio Beacon (NDB) placed in the vicinity of the airport (Attidiya) and used with an Automatic Direction Finder (ADF) on board the aircraft. A needle over a compass dial pointed to Attidiya and gave directional guidance to international air traffic. Although it could accommodate an unlimited number of aircraft, when they needed it most, like during thunderstorm activity, there was static interference and the needles pointed towards the thunder storms instead of Attidiya. So, a Very High Frequency Omnidirectional Radio Range known as a ‘VOR’ for short was installed for more accuracy and free from interference.

Then in 1968, Ratmalana International Airport lost its ‘International’ status when the new Bandaranaike International Airport opened and all international operations moved to Katunayake. The equipment at the airport was allowed to deteriorate. The Radio Navigational letdown aids ran down. There was no proper Control Tower. Even the runway lights were not working and night flights had to depend on Kerosene Lamps. One redeeming grace, in the night, in those days, was that the Sapugaskanda Oil Refinery was in full production and the giant flare of the burning gasses was the guiding light to the Ratmalana Airport. The Pilots spotted the flare from far away and flew over the Refinery and then turned on the runway heading and could see the runway edge kerosene flares, flickering dimly in a dark patch that was the Ratmalana airport! The civil training aircraft of the Government Flying School of those days had neither radios nor any radio aids to navigation.

After 1977, the then UNP government created another problem for Ratmalana operations. The authorities decided to build a new Capital in Sri Jayewardenepura, Kotte and also move the New Parliament to that neck of the woods. Unfortunately, the Parliament was just 3.6 Nautical Miles from the end of the Ratmalana runway ‘as the crow flies’ and less than 1NM from the Thalangama Transmitters. In most countries overflying the Parliament is prohibited. Therefore, the Authorities blindly decreed the same in Sri Lanka. Thus, restricting the freedom of aircraft movements to the Ratmalana Runway and preventing safer, conventional landing approaches. It must be noted that Air Ceylon and other domestic flights were still using Ratmalana. Many professionals were quick to observe that it was akin to someone building a house near a railway line and then complaining that it was too noisy and requiring the railway to divert!

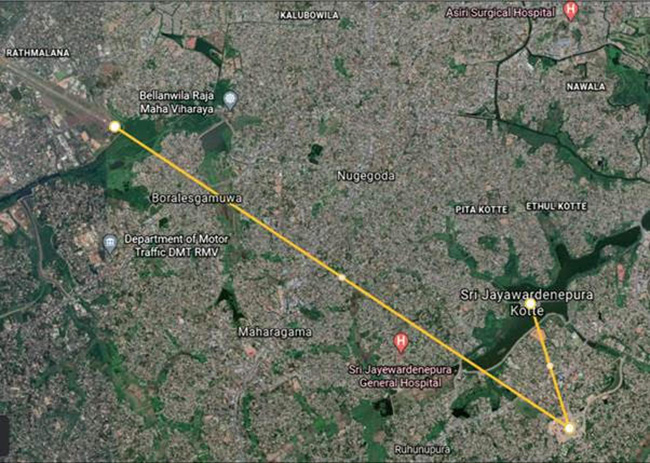

Everyone had learnt to live with the non-availability of precision Navigational aids at Ratmalana. Thalangama Transmitters lost its significance. The Urban Development Authority (UDA) eventually took vacant possession and the SL Army (Gemunu watch) established a camp there. During December, with clear nights and cooler mornings, (Temperature inversions) combined with the North Easterly winds blowing smoke from the Sapugaskanda Refinery, the visibility on the final approach tends to get very bad at the Ratmalana airport. (See image 1)

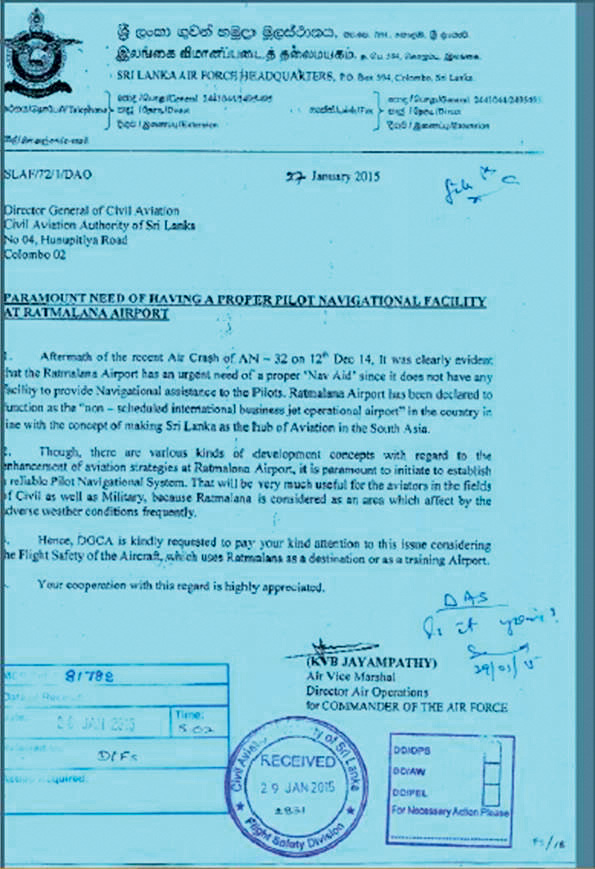

In fact, on the morning of 14 December 2014, an SLAF Antonov AN 32, ferry flight from Katunayake, attempted to approach for landing at Ratmalana and crashed. This prompted the then Air Force Commander to write to the then Director General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) to re-install Navigational Facilities (See Letter below). Now over ten years have gone by and at last Airport and Aviation Sri Lanka (AASL) is slowly waking up to the fact that not only the seen but also the unseen facilities at Ratmalana should be brought up to standard in the name of air safety. Wide publicity is given to the fact that the Government’s intention is to make Ratmalana an International Business aircraft hub and regain its lost glory.

While this concept is being actively pursued by the Airport and Aviation Sri Lanka Ltd (AASL) and the Civil Aviation Authority Sri Lanka (CAASL), another security sensitive building has been erected in the vacant land at Thalangama, barely 1 NM from the Parliament and 4.4 NM from the runway end. That being the Akuregoda Military HeadQuarters. This has created an effective barrier for operation of legitimate air traffic. As a direct result more restrictions are bound to be imposed on inbound air traffic. Furthermore, it does seem like that there was no ‘master plan’ and the left hand didn’t know what the right hand was doing. (See image 3)

Air safety dictates that jet planes should have at least an 8 mile straight in (no turns) final approach. Now it is not possible to do that with the unplanned security sensitive buildings on the final approach to Ratmalana. Ideally, like in other countries, all parties, the Local Municipality Town Planner, the Civil Aviation Authority/ Airport and Aviation Ltd (CAASL/ AASL), and the Building developer, must make these long-term decisions. In Australia for instance the CAA’ Airports Authority has control of man-made obstacles for a radius of 25 miles. Unplanned buildings, called ‘man made relief’ as against ‘Geographic Relief’ (terrain) has spoiled the feasibility of the intended City Airport. Another case in point is the Kotelawala Defence University (K DU). Which is the tallest building in the vicinity of the airport that should never have been allowed to be built that high. This seems to be the malady this whole country is suffering from. The people in the know are afraid to speak up. Subsequently, no one is held accountable for these poor, uncoordinated decisions. The true professionals are not consulted. As a result, vision is ‘tunnelled’. The Sinhala saying Leda malath, bada suddai seems to be very appropriate. (Although the patient died, the bowels were clean!).

The Ratmalana Airport lacks a proper Control Tower with a 360 degree visibility of the area. A new Control Tower could be sited in the highest point in the vicinity. Perhaps at KDU to mitigate the hopeless situation. The Wellington, New Zealand Control Tower is on top of a Shopping Mall! (Seem image 4)

It has also been discovered that the Sri Lanka Air Force Museum building interferes with the navigational and landing aids, radio transmissions at the Ratmalana Airport, if and when installed.

The Parliament has just approved 3 billion rupees for the development of the Ratmalana Airport. For what? Does the government have a plan? Can they reveal their intentions to the aviation professionals?

Are they willing to think out of the box to bring the airport up to scratch? Will it be a waste of time and money? Usually what happens in matters such as this is that they will spend money on structures that can be seen like Terminal Buildings and ignore all the unseen safety related improvements. The Aircraft Owners and Operators Association, Sri Lanka has provided the Minister and his team a ‘wish list’ of fifty improvements that can be done in Domestic Aviation. Perhaps this 3 billion Rupees could be used for implementing those suggestions.

by Capt. G A Fernando MBA (UK) ✍️

gafplane@sltnet.lk

Former President, Aircraft Owners and Operators Association

RCyAF/ SLAF, Air Ceylon, Air Lanka, Singapore Airlines (SIA), SriLankan Airlines

Representative for ‘Aviation’ Oganisation of Professional Associations (OPA), Sri Lanka

President, UL Club

President, The Colombo Flying Club

Features

Rebuilding Sri Lanka Through Inclusive Governance

In the immediate aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah, the government has moved swiftly to establish a Presidential Task Force for Rebuilding Sri Lanka with a core committee to assess requirements, set priorities, allocate resources and raise and disburse funds. Public reaction, however, has focused on the committee’s problematic composition. All eleven committee members are men, and all non-government seats are held by business personalities with no known expertise in complex national development projects, disaster management and addressing the needs of vulnerable populations. They belong to the top echelon of Sri Lanka’s private sector which has been making extraordinary profits. The government has been urged by civil society groups to reconsider the role and purpose of this task force and reconstitute it to be more representative of the country and its multiple needs.

The group of high-powered businessmen initially appointed might greatly help mobilise funds from corporates and international donors, but this group may be ill equipped to determine priorities and oversee disbursement and spending. It would be necessary to separate fundraising, fund oversight and spending prioritisation, given the different capabilities and considerations required for each. International experience in post disaster recovery shows that inclusive and representative structures are more likely to produce outcomes that are equitable, efficient and publicly accepted. Civil society, for instance, brings knowledge rooted in communities, experience in working with vulnerable groups and a capacity to question assumptions that may otherwise go unchallenged.

A positive and important development is that the government has been responsive to these criticisms and has invited at least one civil society representative to join the Rebuilding Sri Lanka committee. This decision deserves to be taken seriously and responded to positively by civil society which needs to call for more representation rather than a single representative. Such a demand would reflect an understanding that rebuilding after a national disaster cannot be undertaken by the state and the business community alone. The inclusion of civil society will strengthen transparency and public confidence, particularly at a moment when trust in institutions remains fragile. While one appointment does not in itself ensure inclusive governance, it opens the door to a more participatory approach that needs to be expanded and institutionalised.

Costly Exclusions

Going down the road of history, the absence of inclusion in government policymaking has cost the country dearly. The exclusion of others, not of one’s own community or political party, started at the very dawn of Independence in 1948. The Father of the Nation, D S Senanayake, led his government to exclude the Malaiyaha Tamil community by depriving them of their citizenship rights. Eight years later, in 1956, the Oxford educated S W R D Bandaranaike effectively excluded the Tamil speaking people from the government by making Sinhala the sole official language. These early decisions normalised exclusion as a tool of governance rather than accommodation and paved the way for seven decades of political conflict and three decades of internal war.

Exclusion has also taken place virulently on a political party basis. Both of Sri Lanka’s post Independence constitutions were decided on by the government alone. The opposition political parties voted against the new constitutions of 1972 and 1977 because they had been excluded from participating in their design. The proposals they had made were not accepted. The basic law of the country was never forged by consensus. This legacy continues to shape adversarial politics and institutional fragility. The exclusion of other communities and political parties from decision making has led to frequent reversals of government policy. Whether in education or economic regulation or foreign policy, what one government has done the successor government has undone.

Sri Lanka’s poor performance in securing the foreign investment necessary for rapid economic growth can be attributed to this factor in the main. Policy instability is not simply an economic problem but a political one rooted in narrow ownership of power. In 2022, when the people went on to the streets to protest against the government and caused it to fall, they demanded system change in which their primary focus was corruption, which had reached very high levels both literally and figuratively. The focus on corruption, as being done by the government at present, has two beneficial impacts for the government. The first is that it ensures that a minimum of resources will be wasted so that the maximum may be used for the people’s welfare.

Second Benefit

The second benefit is that by focusing on the crime of corruption, the government can disable many leaders in the opposition. The more opposition leaders who are behind bars on charges of corruption, the less competition the government faces. Yet these gains do not substitute for the deeper requirement of inclusive governance. The present government seems to have identified corruption as the problem it will emphasise. However, reducing or eliminating corruption by itself is not going to lead to rapid economic development. Corruption is not the sole reason for the absence of economic growth. The most important factor in rapid economic growth is to have government policies that are not reversed every time a new government comes to power.

For Sri Lanka to make the transition to self-sustaining and rapid economic development, it is necessary that the economic policies followed today are not reversed tomorrow. The best way to ensure continuity of policy is to be inclusive in governance. Instead of excluding those in the opposition, the mainstream opposition in particular needs to be included. In terms of system change, the government has scored high with regard to corruption. There is a general feeling that corruption in the country is much reduced compared to the past. However, with regard to inclusion the government needs to demonstrate more commitment. This was evident in the initial choice of cabinet ministers, who were nearly all men from the majority ethnic community. Important committees it formed, including the Presidential Task Force for a Clean Sri Lanka and the Rebuilding Sri Lanka Task Force, also failed at first to reflect the diversity of the country.

In a multi ethnic and multi religious society like Sri Lanka, inclusivity is not merely symbolic. It is essential for addressing diverse perspectives and fostering mutual understanding. It is important to have members of the Tamil, Muslim and other minority communities, and women who are 52 percent of the population, appointed to important decision making bodies, especially those tasked with national recovery. Without such representation, the risk is that the very communities most affected by the crisis will remain unheard, and old grievances will be reproduced in new forms. The invitation extended to civil society to participate in the Rebuilding Sri Lanka Task Force is an important beginning. Whether it becomes a turning point will depend on whether the government chooses to make inclusion a principle of governance rather than treat it as a show of concession made under pressure.

by Jehan Perera

Features

Reservoir operation and flooding

Former Director General of Irrigation, G.T. Dharmasena, in an article, titled “Revival of Innovative systems for reservoir operation and flood forecasting” in The Island of 17 December, 2025, starts out by stating:

“Most reservoirs in Sri Lanka are agriculture and hydropower dominated. Reservoir operators are often unwilling to acknowledge the flood detention capability of major reservoirs during the onset of monsoons. Deviating from the traditional priority for food production and hydropower development, it is time to reorient the operational approach of major reservoirs operators under extreme events, where flood control becomes a vital function. While admitting that total elimination of flood impacts is not technically feasible, the impacts can be reduced by efficient operation of reservoirs and effective early warning systems”.

Addressing the question often raised by the public as to “Why is flooding more prominent downstream of reservoirs compared to the period before they were built,” Mr. Dharmasena cites the following instances: “For instance, why do (sic) Magama in Tissamaharama face floods threats after the construction of the massive Kirindi Oya reservoir? Similarly, why does Ambalantota flood after the construction of Udawalawe Reservoir? Furthermore, why is Molkawa, in the Kalutara District area, getting flooded so often after the construction of Kukule reservoir”?

“These situations exist in several other river basins, too. Engineers must, therefore, be mindful of the need to strictly control the operation of the reservoir gates by their field staff. (Since) “The actual field situation can sometimes deviate significantly from the theoretical technology… it is necessary to examine whether gate operators are strictly adhering to the operational guidelines, as gate operation currently relies too much on the discretion of the operator at the site”.

COMMENT

For Mr. Dharmasena to bring to the attention of the public that “gate operation currently relies too much on the discretion of the operator at the site”, is being disingenuous, after accepting flooding as a way of life for ALL major reservoirs for decades and not doing much about it. As far as the public is concerned, their expectation is that the Institution responsible for Reservoir Management should, not only develop the necessary guidelines to address flooding but also ensure that they are strictly administered by those responsible, without leaving it to the arbitrary discretion of field staff. This exercise should be reviewed annually after each monsoon, if lives are to be saved and livelihoods are to be sustained.

IMPACT of GATE OPERATION on FLOODING

According to Mr. Dhamasena, “Major reservoir spillways are designed for very high return periods… If the spillway gates are opened fully when reservoir is at full capacity, this can produce an artificial flood of a very large magnitude… Therefore, reservoir operators must be mindful in this regard to avoid any artificial flood creation” (Ibid). Continuing, he states: “In reality reservoir spillways are often designed for the sole safety of the reservoir structure, often compromising the safety of the downstream population. This design concept was promoted by foreign agencies in recent times to safeguard their investment for dams. Consequently, the discharge capacities of these spill gates significantly exceed the natural carrying capacity of river(s) downstream” (Ibid).

COMMENT

The design concept where priority is given to the “sole safety of the structure” that causes the discharge capacity of spill gates to “significantly exceed” the carrying capacity of the river is not limited to foreign agencies. Such concepts are also adopted by local designers as well, judging from the fact that flooding is accepted as an inevitable feature of reservoirs. Since design concepts in their current form lack concern for serious destructive consequences downstream and, therefore, unacceptable, it is imperative that the Government mandates that current design criteria are revisited as a critical part of the restoration programme.

CONNECTIVITY BETWEEN GATE OPENINGS and SAFETY MEASURES

It is only after the devastation of historic proportions left behind by Cyclone Ditwah that the Public is aware that major reservoirs are designed with spill gate openings to protect the safety of the structure without factoring in the consequences downstream, such as the safety of the population is an unacceptable proposition. The Institution or Institutions associated with the design have a responsibility not only to inform but also work together with Institutions such as Disaster Management and any others responsible for the consequences downstream, so that they could prepare for what is to follow.

Without working in isolation and without limiting it only to, informing related Institutions, the need is for Institutions that design reservoirs to work as a team with Forecasting and Disaster Management and develop operational frameworks that should be institutionalised and approved by the Cabinet of Ministers. The need is to recognize that without connectivity between spill gate openings and safety measures downstream, catastrophes downstream are bound to recur.

Therefore, the mandate for dam designers and those responsible for disaster management and forecasting should be for them to jointly establish guidelines relating to what safety measures are to be adopted for varying degrees of spill gate openings. For instance, the carrying capacity of the river should relate with a specific openinig of the spill gate. Another specific opening is required when the population should be compelled to move to high ground. The process should continue until the spill gate opening is such that it warrants the population to be evacuated. This relationship could also be established by relating the spill gate openings to the width of the river downstream.

The measures recommended above should be backed up by the judicious use of the land within the flood plain of reservoirs for “DRY DAMS” with sufficient capacity to intercept part of the spill gate discharge from which excess water could be released within the carrying capacity of the river. By relating the capacity of the DRY DAM to the spill gate opening, a degree of safety could be established. However, since the practice of demarcating flood plains is not taken seriously by the Institution concerned, the Government should introduce a Bill that such demarcations are made mandatory as part of State Land in the design and operation of reservoirs. Adopting such a practice would not only contribute significantly to control flooding, but also save lives by not permitting settlement but permitting agricultural activities only within these zones. Furthermore, the creation of an intermediate zone to contain excess flood waters would not tax the safety measures to the extent it would in the absence of such a safety net.

CONCLUSION

Perhaps, the towns of Kotmale and Gampola suffered severe flooding and loss of life because the opening of spill gates to release the unprecedented volumes of water from Cyclone Ditwah, was warranted by the need to ensure the safety of Kotmale and Upper Kotmale Dams.

This and other similar disasters bring into focus the connectivity that exists between forecasting, operation of spill gates, flooding and disaster management. Therefore, it is imperative that the government introduce the much-needed legislative and executive measures to ensure that the agencies associated with these disciplines develop a common operational framework to mitigate flooding and its destructive consequences. A critical feature of such a framework should be the demarcation of the flood plain, and decree that land within the flood plain is a zone set aside for DRY DAMS, planted with trees and free of human settlements, other than for agricultural purposes. In addition, the mandate of such a framework should establish for each river basin the relationship between the degree to which spill gates are opened with levels of flooding and appropriate safety measures.

The government should insist that associated Agencies identify and conduct a pilot project to ascertain the efficacy of the recommendations cited above and if need be, modify it accordingly, so that downstream physical features that are unique to each river basin are taken into account and made an integral feature of reservoir design. Even if such restrictions downstream limit the capacities to store spill gate discharges, it has to be appreciated that providing such facilities within the flood plain to any degree would mitigate the destructive consequences of the flooding.

By Neville Ladduwahetty

Features

Listening to the Language of Shells

The ocean rarely raises its voice. Instead, it leaves behind signs — subtle, intricate and enduring — for those willing to observe closely. Along Sri Lanka’s shores, these signs often appear in the form of seashells: spiralled, ridged, polished by waves, carrying within them the quiet history of marine life. For Marine Naturalist Dr. Malik Fernando, these shells are not souvenirs of the sea but storytellers, bearing witness to ecological change, resilience and loss.

“Seashells are among the most eloquent narrators of the ocean’s condition,” Dr. Fernando told The Island. “They are biological archives. If you know how to read them, they reveal the story of our seas, past and present.”

A long-standing marine conservationist and a member of the Marine Subcommittee of the Wildlife & Nature Protection Society (WNPS), Dr. Fernando has dedicated much of his life to understanding and protecting Sri Lanka’s marine ecosystems. While charismatic megafauna often dominate conservation discourse, he has consistently drawn attention to less celebrated but equally vital marine organisms — particularly molluscs, whose shells are integral to coastal and reef ecosystems.

“Shells are often admired for their beauty, but rarely for their function,” he said. “They are homes, shields and structural components of marine habitats. When shell-bearing organisms decline, it destabilises entire food webs.”

Sri Lanka’s geographical identity as an island nation, Dr. Fernando says, is paradoxically underrepresented in national conservation priorities. “We speak passionately about forests and wildlife on land, but our relationship with the ocean remains largely extractive,” he noted. “We fish, mine sand, build along the coast and pollute, yet fail to pause and ask how much the sea can endure.”

Through his work with the WNPS Marine Subcommittee, Dr. Fernando has been at the forefront of advocating for science-led marine policy and integrated coastal management. He stressed that fragmented governance and weak enforcement continue to undermine marine protection efforts. “The ocean does not recognise administrative boundaries,” he said. “But unfortunately, our policies often do.”

He believes that one of the greatest challenges facing marine conservation in Sri Lanka is invisibility. “What happens underwater is out of sight, and therefore out of mind,” he said. “Coral bleaching, mollusc depletion, habitat destruction — these crises unfold silently. By the time the impacts reach the shore, it is often too late.”

Seashells, in this context, become messengers. Changes in shell thickness, size and abundance, Dr. Fernando explained, can signal shifts in ocean chemistry, rising temperatures and increasing acidity — all linked to climate change. “Ocean acidification weakens shells,” he said. “It is a chemical reality with biological consequences. When shells grow thinner, organisms become more vulnerable, and ecosystems less stable.”

Seashells, in this context, become messengers. Changes in shell thickness, size and abundance, Dr. Fernando explained, can signal shifts in ocean chemistry, rising temperatures and increasing acidity — all linked to climate change. “Ocean acidification weakens shells,” he said. “It is a chemical reality with biological consequences. When shells grow thinner, organisms become more vulnerable, and ecosystems less stable.”

Climate change, he warned, is no longer a distant threat but an active force reshaping Sri Lanka’s marine environment. “We are already witnessing altered breeding cycles, migration patterns and species distribution,” he said. “Marine life is responding rapidly. The question is whether humans will respond wisely.”

Despite the gravity of these challenges, Dr. Fernando remains an advocate of hope rooted in knowledge. He believes public awareness and education are essential to reversing marine degradation. “You cannot expect people to protect what they do not understand,” he said. “Marine literacy must begin early — in schools, communities and through public storytelling.”

It is this belief that has driven his involvement in initiatives that use visual narratives to communicate marine science to broader audiences. According to Dr. Fernando, imagery, art and heritage-based storytelling can evoke emotional connections that data alone cannot. “A well-composed image of a shell can inspire curiosity,” he said. “Curiosity leads to respect, and respect to protection.”

Shells, he added, also hold cultural and historical significance in Sri Lanka, having been used for ornamentation, ritual objects and trade for centuries. “They connect nature and culture,” he said. “By celebrating shells, we are also honouring coastal communities whose lives have long been intertwined with the sea.”

However, Dr. Fernando cautioned against romanticising the ocean without acknowledging responsibility. “Celebration must go hand in hand with conservation,” he said. “Otherwise, we risk turning heritage into exploitation.”

He was particularly critical of unregulated shell collection and commercialisation. “What seems harmless — picking up shells — can have cumulative impacts,” he said. “When multiplied across thousands of visitors, it becomes extraction.”

As Sri Lanka continues to promote coastal tourism, Dr. Fernando emphasised the need for sustainability frameworks that prioritise ecosystem health. “Tourism must not come at the cost of the very environments it depends on,” he said. “Marine conservation is not anti-development; it is pro-future.”

Dr. Malik Fernando

Reflecting on his decades-long engagement with the sea, Dr. Fernando described marine conservation as both a scientific pursuit and a moral obligation. “The ocean has given us food, livelihoods, climate regulation and beauty,” he said. “Protecting it is not an act of charity; it is an act of responsibility.”

He called for stronger collaboration between scientists, policymakers, civil society and the private sector. “No single entity can safeguard the ocean alone,” he said. “Conservation requires collective stewardship.”

Yet, amid concern, Dr. Fernando expressed cautious optimism. “Sri Lanka still has immense marine wealth,” he said. “Our reefs, seagrass beds and coastal waters are resilient, if given a chance.”

Standing at the edge of the sea, shells scattered along the sand, one is reminded that the ocean does not shout its warnings. It leaves behind clues — delicate, enduring, easily overlooked. For Dr. Malik Fernando, those clues demand attention.

“The sea is constantly communicating,” he said. “In shells, in currents, in changing patterns of life. The real question is whether we, as a society, are finally prepared to listen — and to act before silence replaces the story.”

By Ifham Nizam

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoBritish MP calls on Foreign Secretary to expand sanction package against ‘Sri Lankan war criminals’

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoChief selector’s remarks disappointing says Mickey Arthur

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoStreet vendors banned from Kandy City

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoSri Lanka’s coastline faces unfolding catastrophe: Expert

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoDisasters do not destroy nations; the refusal to change does

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoLankan aircrew fly daring UN Medevac in hostile conditions in Africa

-

Midweek Review6 days ago

Midweek Review6 days agoYear ends with the NPP govt. on the back foot

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoLife after the armband for Asalanka