Features

Vijaya Nandasiri : Losing it in laughs

By Uditha Devapriya

Vijaya Nandasiri left us six years ago. The epitome of mass market comedy in Sri Lanka, Nandasiri belonged to a group of humourists, which included Rodney Warnapura and Giriraj Kaushalya, who redefined satire in the country. Nandasiri’s aesthetic was not profound, nor was it subtle. It was not aimed at a particular segment. Indeed, there was nothing elitist or pretentious about it; if you could take to it, you took to it. It was hard not to laugh at him, it was hard not to like him. Indeed, it was hard not to sympathise with him.

In the movies, Sri Lanka’s first great humourist was Eddie Jayamanne. Typically cast as the servant or bumpkin, Jayamanne could never let go of his theatrical roots. More often than not his laughs targeted a particular segment, so much so that when Lester Peries cast him as the father of the hero’s lover in Sandesaya, he still seemed stuck in those movies he had made and starred in with Rukmani Devi. Many years later he was cast as a close friend of the protagonist in Kolamba Sanniya, in many ways Sri Lanka’s equivalent of It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. Even there, he could not quite escape his origins.

In Kolamba Sanniya, Jayamanne played opposite Joe Abeywickrema. Hailing from a different background, more rural than suburban, Abeywickrema had by then become our greatest character actor. Dabbling in comedy for so long, he found a different niche after Mahagama Sekara cast him in Thunman Handiya and D. B. Nihalsinghe featured him as Goring Mudalali in Welikathara. Yet he could never let go of his comic garb. Cast for the most as an outsider in the cities and the suburbs – of whom the epitome has to be the protagonist of Kolamba Sanniya – Abeywickrema discovered his élan in the role of the man who falls into a series of absurd situations, but remains unflappably calm no matter what.

There is nothing profoundly or intellectually funny in Kolamba Sanniya. Like It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, the humour emerges from the characters’ imperfections and foibles: their way of looking at the world, their accents, their lack of polish and elegance. The dialogues are not convincing, and some of the situations – like the hero’s family discovering a bidet for the very first time – are downright silly, if not condescending. What strengthens the story is Joe Abeywickrema’s performance; specifically, his ability to convince us that, despite the situations he is being put through, he can stand on his own. Like the protagonist of Punchi Baba, left to take care of an abandoned baby, he is helpless but not lacking control. He often makes us think he’s losing it, but then gets back on track.

Vijaya Nandasiri was cut from a different cloth. In many respects he was Abeywickrema’s descendant, yet in many others he differed from him. Whereas Abeywickrema discovered his niche playing characters who could conceal the absurdity of the situations they were in, Nandasiri’s characters could only fail miserably. Abeywickrema convinced us that he was in control; Nandasiri could not. As Rajamanthri, the politician who for most of us epitomised the silliness and stupidity of our brand of lawmakers, he frequently parrots out that he’s an honest man. Abeywickrema could say the same thing and get away with it. Nandasiri could not: when he says he’s honest, you knew at once that he was anything but.

Nandasiri revelled in having no self-respect even when we ascribed to him some sense of honour and dignity. In Nonawarune Mahathwarune the ubiquitous Premachandra flirts with the woman next door (Sanoja Bibile), though we don’t get why the latter never returns his affections. As Senarath Dunusinghe in Yes Boss, the situation is reversed: he has to suffer another man flirting with his wife, the issue being that the man happens to be his employer who doesn’t know that they are married. The whole plot pivots on two things: the fact that his boss doesn’t like him, and the fact that he has to disguise himself as an older husband of his own wife to conceal their marriage from his boss.

In his own special way, Nandasiri went on to represent our contempt for womanisers, cuckolds, and politicians, by turning them into easily recognisable and easily mockable stereotypes. In Nonawarune Mahathwarune he was the womaniser, in Yes Boss he was the cuckold – though his wife only pretends to give in to their employer’s advances – and as Rajamanthri, easily the most recognisable comic figure here during the past 20 years, he was the politician. It was as Rajamanthri that he prospered, even when playing characters who only vaguely reminded us of him, such as the antihero of Sikuru Hathe.

Many years ago, I watched a mini series on Rupavahini revolving around a politician and his driver. Vijaya Nandasiri played the politician, Vasantha Kumarasiri’s driver. Early on I sensed something odd about them. Their voices were different. The dubbing team had synced one actor’s voice with the other, a trick that survived the first 10 minutes of the first episode, after which these two meet a horrible accident that (inexplicably) leaves onlookers and relatives confused as to whose body belongs to whom.

Both are near dying. A quick surgery is hence followed by a quick plastic surgery, in which the wrong face is placed on the wrong body. The voices now revert to the correct actor. In hindsight this was an unnecessary gimmick, but also a useful trick, since for the rest of the story the driver becomes the believer in authority and the politician the believer in Marxist politics. Crude, and rather one-dimensional, but fun. And it wasn’t just a change of voice: it was also a change of spirit, of two contradictory personalities transplanted to each other. That was Nandasiri’s charm. You could never anticipate anyone other than him when he was there. For the mini series to work, hence, he had to be himself.

If Joe was redeemable because he was at the receiving end of some confusing dilemma (like the baby he raises in Punchi Baba, or the lifestyle in Colombo he gets used to in Kolamba Sanniya, Vijaya was unredeemable because he was at the other end, always provoking if not unleashing some havoc. It’s not a coincidence that, in this respect, his characters were always middle class, consumerist, very often in professions that called for security, stability, and status: as a Junior Visualiser in an ad agency in Yes Boss, as the chief in a security firm in Sir Last Chance, and as a police sergeant in Magodi Godayi. These symbolised a lifestyle that Nandasiri’s antiheroes sought to subvert and to defy.

Where he was his own man – the magul kapuwa in Sikuru Hathe or Rajamanthri in so many movies and serials – he wasn’t a provocateur, but a lovable antihero. And like all antiheroes, he conceals goodness because he despises it: in Sikuru Hathe, for instance, he commits one deception after another for his family’s sake, especially his daughter’s.

Where he was paired with another actor, I think, Nandasiri failed. He was his man, so when in Methuma he and Sriyantha Mendis are mistaken for two lunatics by a veda mahaththaya in a village, he could not really shine the way he had in Ethuma. Even in Magodi Godayi, he was less than he usually was whenever he was opposite Gamini Susiriwardana. Yes Boss and Nonawarune Mahathwarune had him among a plethora of other actors, to be sure, but then he was on his own there. There are moments in Yes Boss when Lucky Dias nearly outshines him. But Nandasiri gets back on track; he exerts his dominance again.

In other words, Nandasiri could give his best only if his co-star was alive to his range, or if his character was of a lesser pedigree than his co-star. That is what happens in King Hunther, where he could be himself opposite Mahendra Perera for two reasons: because Mahendra was a fairly good comic actor himself, and because Nandasiri’s character, Hunther, hails from such a different world that the present (in which Mahendra is an escaped convict) appears outlandish to him. Hunther to get used to this world, and that means getting used to the first two people he befriends: Mahendra and Anarkali Akarsha.

Vijaya Nandasiri’s ultimate triumph was his gift at getting us to feel for unfeeling antiheroes. Sometimes he could trump us, as Abeywickrema often did, like in King Hunther, when he hears that the politician who befriends him to further his career has decided to kill him off, and surreptitiously escapes. You never thought he was capable of upping the antagonist, but he does just that, providing us with the final twist in the story.

He couldn’t behave this way as Rajamanthri because he was not reflecting our contempt for figures of authority, but downright embodying it. When, towards the end of Suhada Koka, he is killed off by an assassin acting on the orders of the second-in-command to the Prime Minister (the latter played by W. Jayasiri), the film preaches to us a homily on the corrupting influence of power, a warning for all politicians. But then, just as you come to terms with this conclusion, he wakes up; the whole scene, it turns out, was a nightmare.

Ordinarily, you’d think he would learn from such a nightmare. But he doesn’t. Even after that harrowing fantasy, he is soon back to being the pompous figure he always was. Yet in that brief sequence he told us everything that needed to be told about how the corrupt remain corrupt, and how irredeemable they are. Was it a cruel coincidence, then, that the only time Rajamanthri was killed off like that marked the last time Vijaya Nandasiri played Rajamanthri? We may never know, but perhaps it was more than a coincidence. Perhaps it was the only fitting end to such a career that could be filmed.The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

Features

Defining Oxygen Economy for sustaining life on Earth and growing intergenerational wealth

by Dr. Ranil Senanayake

The Oxygen that is present in the air that we breathe is the birth right of every organism that lives on this planet. It is free for everyone. However, the action of some to take out more than their share, without replacement, has created a condition, where the Global Commons of air is being rapidly degraded,

The most critical component of air is Oxygen. It surrounds us, filling our lungs with every breath we take. It is the invisible gift of nature that we take for granted. But this essential resource—the very foundation of life— is being constricted, because the volume of trees, plants, and photosynthetic organisms that produce oxygen is being lost across the planet. Further, there is no initiative for this generation capacity to be increased as a matter of urgency. exploited at present? Why couldn’t increasing the generation capacity of Oxygen have economic value? Could those who benefit most from using the resources of the Global Commons be required to contribute to its maintenance? This is the idea behind the Oxygen Economy, a bold and transformative concept that seeks to address environmental and social challenges in a way that is fair, sustainable, and forward-thinking beyond GDP value which measures the success of our societies today.

What Is the Oxygen Economy?

The Oxygen Economy is a financial framework, that recognises the value of the global stocks of Oxygen within the commons and records the deposition and consumption through economic activity.

The Oxygen Economy is a principled framework that recognises the stocks, transactions and deposits of Oxygen into the Global commons and assigns value to stocks from privately contracted production units, it stems from a growing recognition that Oxygen is a declining resource with an easy replenishment response.

Oxygen, considered a “free” resource. It is not. Much like oil and coal it is a ‘fossil’ resource that has been a part of the atmosphere for millions of years. It has been slowly declining, but is ‘topped up’ by a service provided by the earth’s ecosystems —particularly trees, plants, and other photosynthetic organisms. These organisms create molecular Oxygen through the process of photosynthesis, supporting life on earth and maintaining the balance of our atmosphere.

At its core, the Oxygen Economy aims to ensure that those who produce contracted and monitored oxygen, be it towns, farmlands, rural or forested lands, are fairly compensated for their efforts. It also holds industries and private-sector entities that benefit from oxygen consumption accountable in maintaining the sustainability of this resource.

What is the urgency to address oxygen as a depleting resource?

Other than the obvious fact of falling global stocks, the need of an Oxygen Economy arises from the urgency of addressing two critical challenges facing humanity: environmental degradation and economic inequality. Placing value on Oxygen production could effectively provide an effective response to both. For decades, efforts to combat climate change have focused primarily on carbon

sequestration. While important, the focus on Carbon sequestration often overlooks other vital ecosystem services, including oxygen production that can contribute towards a growing wealth paradigm. Oxygen, like water and food, is essential for life. However, unlike other resources, it has largely been treated as infinite and freely available, which it is not. In reality, the supply of Oxygen to the atmosphere is decreasing due to deforestation, while the consumption of Oxygen by space exploration, industrial production, war and transport are increasing. Today Oxygen levels have dropped by approximately 2%, raising concerns about the long- term sustainability of this critical resource.

How the Oxygen Economy works

The Oxygen Economy operates on the principles of private property being valued using financial tools such as valuation guarantees, stakeholder contracts and Insurances to monetise contractually produced oxygen as a financial product. This involves three key components:

1. Valuation guarantee:

Assigning an economic value to the oxygen produced by contracted and registered units in identified geographical areas of production is based on the researched, monitored and validated measurements of oxygen generation by trees / plants or photosynthetic organisms such as Cyanobacteria.

2. Deposition guarantee:

Issuance of certificates of completion and deposit of Oxygen into the global Commons Stakeholder Contracts and Compensation: Establishing formal agreements between oxygen consumers (e. g., corporations / Space exploration companies) and contracted oxygen producers (e.g., farmers, Local communities)

3. Policy and regulation: Introducing replicable legal frameworks at a regional scale to enforce accountability and prevent the uncontrolled exploitation of global oxygen resources.

Lessons from Sri Lanka

One country that is already exploring the potential of the Oxygen Economy is in the bioregional area of Sri Lanka. Known for its rich biodiversity and commitment to environmental stewardship, Sri Lanka has implemented initiatives that align with the principles of the Oxygen Economy. In one notable project, women from farming communities established and nurtured trees using contracts that measured and validated payments for photosynthetic biomass on an annually recurring basis for a period of four years. The stakeholders earning substantive income from this project were sensitised to the emerging Oxygen Economy while contributing their obligations to global environmental resilience. Over three years, these participants generated thousands of litres of oxygen, demonstrating that the concept is not only viable but also impactful.

Scaling the Oxygen Economy globally:

While Sri Lanka’s efforts are a promising start, the true potential of the Oxygen Economy

lies in its ability to scale globally. Imagine a world where farmers are compensated for the establishment of trees, where rural and even urban greenery projects could receive funding to expand their impact for this paradigm of business. Such a system would not only help combat climate change but also address economic inequalities of the current GDP paradigm, by together contracting the Oxygen economic asset tool to those who sustain the planet’s life-support systems.

Addressing potential challenges

Like any transformative idea, the Oxygen Economy faces potential challenges. Critics may argue that assigning a monetary value to Oxygen risks commodifying a natural resource that should remain freely accessible. Others may question the feasibility of measuring, validating and regulating oxygen production on a global scale. These concerns can be addressed by emphasising the ethical principles behind the Oxygen Economy. The goal is not to charge people for breathing but to ensure that those who contribute to its sustainability profit from financial contracts for Oxygen production. Additionally, such transparent systems for measuring and validating oxygen production will be crucial for building trust and ensuring fairness towards the vision of accounting for intergenerational wealth beyond the GDP framework that exists.

A vision for the future

The Oxygen Economy represents a paradigm shift in how we think about our relationship with the planet. It challenges us to move beyond the notion of nature as an infinite resource and to recognise the boundaries of our Global Commons. The true value of planet Earth is as an ecosystem that sustains life for all biota. By aligning economic practices with environmental stewardship, the Oxygen Economy offers a path towards a more equitable and sustainable future. It supports the foundations of intergenerational wealth that will be reflected in our contributions to the cycling atmospheric gasses of our Global Commons.

Imagine a world where the air we breathe is not taken for granted but is cherished and protected. Where farmers, communities, and ecosystems are rewarded for their contributions to the planet’s well-being. Where industries operate with a framework of accountability to prioritise the health of our shared environment. This is the vision of the Oxygen Economy—a vision that is within our reach if we act together, with urgency and determination, to lay well informed, solid foundations.

Features

Two sides to a coin; each mourn threat; no threat, no budget blues

The coin Cassandra starts her Friday Cry with the recent film Rani. Parroting what her friends said on seeing the film, Cass in her Cry just prior to this wrote: “It has been reviewed as outstanding; raved over by many; and already grossed the highest amount in SL cinema history – Rs 100 million from date of release January 30 to February 14. This last: testimony to its popular appeal and acceptance as an outstanding cinema achievement.

The coin Cassandra starts her Friday Cry with the recent film Rani. Parroting what her friends said on seeing the film, Cass in her Cry just prior to this wrote: “It has been reviewed as outstanding; raved over by many; and already grossed the highest amount in SL cinema history – Rs 100 million from date of release January 30 to February 14. This last: testimony to its popular appeal and acceptance as an outstanding cinema achievement.

” Cass admitted she had not seen the film. She now realises her reluctance to jostle in the crowd in one of many cinemas retelling the murder of Richard de Zoysa and traumatic mourning of his mother, Manorani, was because there grew in her a distaste after watching short previews on YouTube of parts of the film. Most centered on is Swarna Mallawarachchi, starring as Manorani, downing alcohol and smoking cigarette after cigarette. Director Asoka Handagama was sensationlising the more dramatic incidents of the tragedy. That was to please the crowd.

We Sri Lankans, or many, have absolutely no tight upper lip. Most funerals of yesteryear and many rural ones still have writhing moaning and groaning and appeals to the dead to smile one more time, say a word, rise up. These loud gasped cries in between sobbing sent Cass wickedly into silent giggles. She thought: what if the dead obliged with even one request. Worst, if he rose up and sat in his coffin. The first to run away would be the callers! People love wallowing in sniffles of sorrow. Audiences much prefer fictionalised retelling of events to documentaries about them. Handagama does style his film as fictionalised history but he definitely is guilty of sensationalism. Cass’ gut feelings have been given words in a criticism on Face Book which was shared with Cass by a nephew.

The sent around message is titled: Misconceived, Misinterpreted, Miscast and a Big Mistake. That tells it all. However there follows an incisive critique of the film Rani by one of Richard’s friends who knew Manorani well and how she was after her son’s death. He signs himself, but Cass will not quote the name here since there is much truth, lies and even hidden agendas in what is posted on social media.

He writes: “Badly acted, badly directed and badly researched … A clear example of character assassination via a deliberate misuse of artistic license! … I want to state my opinion about two people that many of us loved, respected and knew intimately.” He then goes on to point out mistakes and exaggerations: Manorani was never even bordering on alcoholism and hardly ever smoked. And when she did, socially or to dim her sorrow, she did it elegantly. A Man Friday commented: they should have taught Swarna how to hold a cigarette and smoke it as it should be smoked. Hence my contention, every coin, even a box office success, has two sides to it, two diverse criticisms and in-betweens. Decision: Cass will not queue for a cinema ticket.

Each morn

Phoned a US living friend who was recovering from a harsh winter’s gift to her – severe flu. She said the flu was leaving her but depression and distraught-ness about hers and the US’s future were threatening to drown her in emotional turmoil much worse than the worst cough ‘n cold.

I knew the reason – Trump’s trumpets of new opinions, threats, enactments et al. She dreaded getting up each morning wondering what new calamity was to descend on the American people and by influence, spreading to the world. Her son has forbidden TV news watching and reading the newspapers which she says are so opposed to media treatment of the Prez.

I could very well sympathise with her. We in Sri Lanka suffered bouts of such threatened discomfort, nay calamitous warnings and sheer dread. My remembering mind went to Shakespeare in his tragic play Macbeth. Macduff’s description of Scotland under the reign of Macbeth to Malcolm, son and heir of murdered Duncan now sheltered in England, goes thus: “Each new morn/ New widows howl, new orphans cry/ new sorrows strike heaven on the face that it resounds.”

Cass does not know about you but dread lurked in her heart and mind when the JVP 1989 insurrection took place – for her teenage son. The LTTE and suicide bombs caused utter destruction of life, limb and infrastructure. Families who had travelled together now travelled to schools and workplaces separately since no bus or train was safe. Nor were the privately owned cars. Then came two tyrant Presidents with sudden deaths of prominent persons and media personnel like Richard and Lasantha and many others.

Blatant robbing of our money had us gasping helplessly. Riff raff rose in power and lorded, one such tying a man to a stake for not attending a meeting. Then rode to power on popular vote another brother in the newly created powerful dynasty. Word of mouth minus stroke of pen had orders given out to be promptly executed. White vans which plied the streets were reduced but worse happened.

One order and the rice fields had no grain, fruits dried on trees, forex earning luscious two leaves and a bud withered and could not be plucked. Bankruptcy resulted. But we had a ‘shipless’ harbour which had to be mortgaged for a song to the Chinese; a plane-less airport sounding death to elephants and peafowl; and a gaudy tower to gaze on or commit suicide from. A gathering of people on Galle Face Green righted things.

Then came into power a party that had two men and a woman in Parliament which yielded a true Sri Lankan with country first and last in mind, as President. Followed a sharp victory for the coalition of parties led by the hopefully reformed JVP so that three seats became almost two thirds of all seats in Parliament and a woman as Prime Minister. She had no connection to previous Heads unlike a former woman PM and Prez. The first woman PM rode to power weeping for her murdered husband; the younger very promising Prez because she was daughter of two Heads of Sri Lanka. But there was, even under their reign, mutterings and difficulties.

Truth be told, we sleep better at night and wake up with no dread in our innards. We rise to shine (if possible, in the heat of Feb) knowing people are working and corruption is not wrought by those in power. Thank goodness and our sensible voters for this peace we savour.

2025 Budget

Cass’ title has the phrase ‘no budget blues’. Looks like it is generally correct. Of course, the Opposition is criticising Finance Minister AKD’s presented budget. Cass is no economist, not by a long chalk, but she was glad to see that expenditure on health and education were substantial. We had a time when the armed forces were allocated more than education and health combined. Much has been looked into: including pregnant women and the Jaffna library among a host of mentioned amenities. We have no need to pessimistically await a Gazette Extraordinary stating negative segments of the future year’s financial plan. Thanks be!

Gaza and Ukraine are worse in position and the world is awry. But Sri Lanka is in a phase where Kuveni’s curse is stilled and people are considering themselves Sri Lankans, uniting to re-make Sri Lanka Clean as it was before selfish corrupt politicians took over.

Features

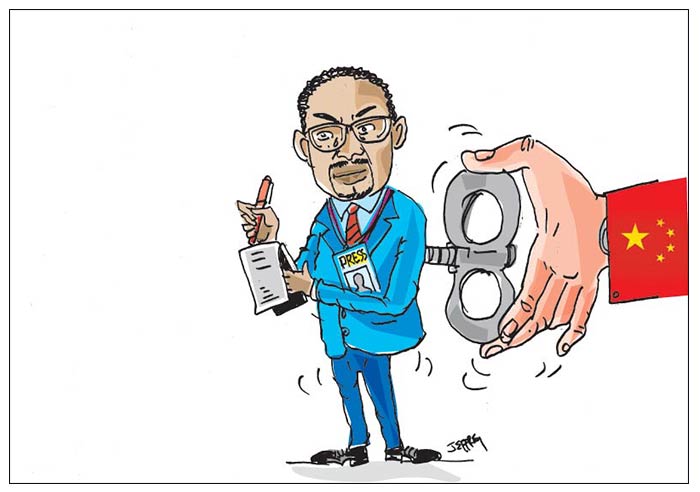

As Africa toes Chinese line …

Mitchell Gallagher

Every year, China’s minister of foreign affairs embarks on what has now become a customary odyssey across Africa. The tradition began in the late 1980s and sees Beijing’s top diplomat visit several African nations to reaffirm ties. The most recent visit, by Foreign Minister Wang Yi, took place in mid-January 2025 and included stops in Namibia, the Republic of the Congo, Chad and Nigeria.

For over two decades, China’s burgeoning influence in Africa was symbolised by grand displays of infrastructural might. From Nairobi’s gleaming towers to expansive ports dotting the continent’s shorelines, China’s investments on the continent have surged, reaching over $700 billion by 2023 under the Belt and Road Initiative, China’s massive global infrastructure development strategy.

But in recent years, Beijing has sought to expand beyond roads and skyscrapers and has made a play for the hearts and minds of African people. With a deft mix of persuasion, power and money, Beijing has turned to African media as a potential conduit for its geopolitical ambitions. Partnering with local outlets and journalist-training initiatives, China has expanded China’s media footprint in Africa. Its purpose? To change perceptions and anchor the idea of Beijing as a provider of resources and assistance and a model for development and governance. The ploy appears to be paying dividends, with evidence of sections of the media giving favourable coverage to China.

But as someone researching the reach of China’s influence overseas, I am beginning to see a nascent backlash against pro-Beijing reporting in countries across the continent. China’s approach to Africa rests mainly on its use of “soft power,” manifested through things like the media and cultural programmes. Beijing presents this as “win-win cooperation”—a quintessential Chinese diplomatic phrase mixing collaboration with cultural diplomacy. Key to China’s media approach in Africa are two institutions: The China Global Television Network (CGTN) Africa and Xinhua News Agency.

CGTN Africa, which was set up in 2012, offers a Chinese perspective on African news. The network produces content in multiple languages, including English, French and Swahili, and its coverage routinely portrays Beijing as a constructive partner, reporting on infrastructure projects, trade agreements and cultural initiatives. Moreover, Xinhua News Agency, China’s state news agency, now boasts 37 bureaus on the continent. By contrast, Western media presence in Africa remains comparatively limited.

The BBC, long embedded due to the United Kingdom’s colonial legacy, still maintains a large footprint among foreign outlets, but its influence is largely historical rather than expanding. And as Western media influence in Africa has plateaued, China’s state-backed media has grown exponentially. This expansion is especially evident in the digital domain. On Facebook, for example, CGTN Africa commands a staggering 4.5 million followers, vastly outpacing CNN Africa, which has 1.2 million—a stark indicator of China’s growing soft power reach. China’s zero-tariff trade policy with 33 African countries showcases how it uses economic policies to mould perceptions.

And state-backed media outlets like CGTN Africa and Xinhua are central to highlighting such projects and pushing an image of China as a benevolent partner. Stories of an “all-weather” or steadfast China-Africa partnership are broadcast widely and the coverage frequently depicts the grand nature of Chinese infrastructure projects. Amid this glowing coverage, the labour disputes, environmental devastation or debt traps associated with some Chinese-built infrastructure are less likely to make headlines. Questions of media veracity notwithstanding, China’s strategy is bearing fruit.

A Gallup poll from April 2024 showed China’s approval ratings climbing in Africa as US ratings dipped. Afrobarometer, a pan-African research organisation, further reports that public opinion of China in many African countries is positively glowing, an apparent validation of China’s discourse engineering. Further, studies have shown that pro-Beijing media influences perceptions. A 2023 survey of Zimbabweans found that those who were exposed to Chinese media were more likely to have a positive view of Beijing’s economic activities in the country. The effectiveness of China’s media strategy becomes especially apparent in the integration of local media.

Through content-sharing agreements, African outlets have disseminated Beijing’s editorial line and stories from Chinese state media, often without the due diligence of journalistic scepticism. Meanwhile, StarTimes, a Chinese media company, delivers a steady stream of curated depictions of translated Chinese movies, TV shows and documentaries across 30 countries in Africa. But China is not merely pushing its viewpoint through African channels. It’s also taking a lead role in training African journalists, thousands of whom have been lured by all-expenses-paid trips to China under the guise of “professional development.” On such junkets, they receive training that critics say obscures the distinction between skill-building and propaganda, presenting them with perspectives conforming to Beijing’s line.

Ethiopia exemplifies how China’s infrastructure investments and media influence have fostered a largely favourable perception of Beijing. State media outlets, often staffed by journalists trained in Chinese-run programmes, consistently frame China’s role as one of selfless partnership. Coverage of projects like the Addis AbabaDjibouti railway line highlights the benefits, while omitting reports on the substandard labour conditions tied to such projects—an approach reflective of Ethiopia’s media landscape, where state-run outlets prioritise economic development narratives and rely heavily on Xinhua as a primary news source. In Angola, Chinese oil companies extract considerable resources and channel billions into infrastructure projects.

The local media, again regularly staffed by journalists who have accepted invitations to visit China, often portray Sino-Angolan relations in glowing terms. Allegations of corruption, the displacement of local communities and environmental degradation are relegated to side notes in the name of common development. Despite all of the Chinese influence, media perspectives in Africa are far from uniformly pro-Beijing. In Kenya, voices of dissent are beginning to rise and media professionals immune to Beijing’s allure are probing the true costs of Chinese financial undertakings. In South Africa, media watchdogs are sounding alarms, pointing to a gradual attrition of press freedoms that come packaged with promises of growth and prosperity.

In Ghana, anxiety about Chinese media influence permeates more than the journalism sector, as officials have raised concerns about the implications of Chinese media cooperation agreements. Wariness in Ghana became especially apparent when local journalists started reporting that Chinese-produced content was being prioritised over domestic stories in state media.

Beneath the surface of China’s well publicised projects and media offerings, and the African countries or organisations that embrace Beijing’s line, a significant countervailing force exists that challenges uncritical representations and pursues rigorous journalism. Yet as CGTN Africa and Xinhua become entrenched in African media ecosystems, a pertinent question comes to the forefront: Will Africa’s journalists and press be able to uphold their impartiality and retain intellectual independence? As China continues to make strategic inroads in Africa, it’s a fair question.

(The writer is a PhD candidate of political science at Wayne State University, US. This article was published on www.theconversation.com)

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoRemarkable turnaround for Sri Lanka’s ODI team

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoScammed and Stranded: The Dark Side of Sri Lanka’s Migration Industry

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoUN Global Compact Network Sri Lanka: Empowering Businesses to Lead Sustainability in 2025 & Beyond

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoDon’t betray baiyas who voted you into power for lack of better alternative: a helpful warning to NPP – II

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoCommercial High Court orders AASSL to pay Rs 176 mn for unilateral termination of contract

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoSri Lanka face Australia in Masters World Cup semi-final today

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoTwo films and comments

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoInnovation Island Summit 2025, Colombo, Sri Lanka