Opinion

Using SORTITION to prevent electing of same crooks to parliament

By Chandre Dharmawardana

chandre.dharma@yahoo.ca

The terrorism of the LTTE ended in May 2009, and most Sri Lankans looked forward to a dawn of peace, reconciliation and progress. Even Poongkothai Chandrahasan, the granddaughter of SJV Chelvanayagam could state that ‘what touched me the most that day was that these were poor people with no agenda ~ wearing their feelings on their sleeves~. Every single person I spoke to said to me, “The war is over, we are so happy”. They were not celebrating the defeat of the Tamils. They were celebrating the fact that now there would be peace in Sri Lanka’ (The Island, 23rd August 2009, http://archive.island.lk/2009/08/23/news15.html).

The dilemma faced by SL

Unfortunately, instead of peace, prosperity and reconciliation, a corrupt oligarchy made up of politicians from the two main parties of the period, namely the UNP, the SLFP, the JVP, their associated business tycoons and NGO bosses have evolved into a cabal of the rich who have hogged the power of parliament among themselves. The party names “UNP, SLFP, JVP” etc., have morphed into other forms, while the leaders concerned have changed adherence to the parties or made alliances with the ease of changing cutlery at a sumptuous banquet.

Periods of civil strife are also periods when corrupt cutthroats thrive, with illegal arms and money in the hands of those on both sides of the conflict who made a career out of the war.

Mahinda Rajapaksa’s SLFP and its allies defeated terrorism and were given a strong mandate by an electorate tired of war to “go forward” in 2010. Unfortunately, as in most cases of “rapid reconstruction” in the wake of a war, the gangrene of corruption of a long war also continued hand in hand. Expensive infrastructure projects, highways and symbolic show pieces that earned lucrative commissions to those in power and to their hangers-on got priority over hard-nosed development projects.

Although the country called itself a “democratic socialist” republic, an essentially libertarian Ayn Randian-type political philosophy coupled with neoliberal economic policies reigned supreme with the Rajapaksa-led governments as well as governments led by the UNP-Sirisena-led SLFP etc., even if this reality was not always articulated clearly. Thus, while public transport, education, public health and alternative-energy projects were neglected, import of luxury goods, highways for wealthy commuters, private hospitals, fossil fuels and organic food for the elite were encouraged by the libertarians. These expensive projects were funded by loans even in the international money market, as long as such monies were available. Public borrowing itself was converted into various types of bond scams.

Ironically enough, both right-wing Rothbardian-type economics as well as extreme left-wing “progressive” economics agreed on printing money with no restrictions, to maintain a false standard of living beyond means.

Not surprisingly, the country had to come to a screeching halt when it became insolvent. Only the rich oligarchs had the means to continue to function as before, and unambiguously assume the levers of political power. Consequently, Ranil Wickremesinghe, the scion of the Sri Lankan libertarians is now in the saddle. Political turmoil is temporarily abated as the power of the political machinery is also in the hands of the same elites who control the economy. While this may be “good for the market” and possibly for the economy in a narrow sense the word “good”, it hides a highly unstable situation where a large majority of the population has become impoverished and desperate. A highly nationalistic army stands by with many of its major figures bought into the elite sector while the common soldiers remain part and parcel of the impoverished peasantry.

The dilemma faced by the country is to defuse this untenable situation by re-distributing political power so that a sustainable economy that ensures at least the basic needs of every one is achieved. The economy of a very small country is completely subject to the vicissitudes of international markets within completely open libertarian policies. Such policies may be very advantages for powerful countries bent on expanding their markets or acquiring sources of raw materials, but not for poor nations.

The key to having some capacity for controlling one’s destiny is to have an economy that is relatively independent of external market forces. Economists have not yet recognized that energy availability (and not class conflict, nor the “freedom” of the market) is the motive force of socio-economic evolution – a fact first enunciated by Ludwig Boltzmann in an address to the German Mathematical society. Boltzmann was an outstanding theoretical physicist of the 19th century. Energy availability can be converted into agricultural and industrial productivity, leading to prosperity and well-being. However, none of the political parties that currently exist in Sri Lanka, sunk in corruption, wheeler-dealing, blinded in ideology, communalism etc., and having scant regard for democratic values or the welfare of its citizens is likely to present a political program that will help the country. In any case, no one trusts them.

In fact, the existing political parties will field the same pack of rogues as candidates for any forthcoming election. The people themselves have little faith in elections, or in politicians, with confidence in public institutions now at a very low ebb. So, apparently, there is no point in having elections!

A solution to dilemma

The need to go beyond the model of elections to ensure democracy has been recognised since the times of Athenian city states. The democracies in ancient Athens chose only ten percent of their officials by election, selecting the rest by sortition—a lottery, which randomly selected citizens to serve as legislators, jurors, magistrates and administrators. Aristotle argued that sortition is the best method of ensuring a democracy, while elected officials become part of oligarchies where the wealthy and powerful manipulate the election process.

Since competence and honesty are characteristics that are randomly and statistically distributed in a society, selecting a set of members of parliament by lottery would provide a representative, fresh “sample” of the voting population. They are not beholden to “party organisers” nor have they come to power using wealth, stealth and thuggery needed to run for office now a days.

Many societies down the ages have experimented with sortition. The councilors of the Italian republic of Genoa during the early renaissance were selected by lottery. Montaigne and Tom Paine had written in favour of using sortition to strengthen democracy. More recently Burnheim in Australia had proposed what he called “demarchy” where random selection of legislators is used. Callenbach and Phillips proposed a Citizens’ Legislature in the US. Sortiton was advocated by the main candidates of the recent presidential election in France in 2017 and used at some levels of electioneering during the first round of the presidential vote. The topic has become mainstream and scholarly works are easily found, though neglected by Sri Lankan writers.

In the case of Sri Lanka, it would be appropriate to select, say half the legislature by sortation. Of course, every one selected by lottery may not want to become a politician even for one term of office. Hence one may choose, say 400 candidates by lottery and a further selection of those who wish to serve can be made. The sortition-selected MPs should have the same entitlements and salary as for an elected MP. If they already hold a job in government, they have would leave the job for one term of office, and revert to their previous livelihoods, or contest as members of a political party. That is, they will be replaced by a new set of MPs selected by sortition.

All this requires constitutional amendments. A country that could amend the constitution even to accommodate influential individuals can surely amend it for the sake of public good? Unfortunately, the sortation model has not yet received the attention of political and constitutional writers of Sri Lanka, although it holds the key to the current impasse.

Opinion

Why religion should remain separate from state power in Sri Lanka: Lessons from political history

Religion has been an essential part of Sri Lankan society for more than two millennia, shaping culture, moral values, and social traditions. Buddhism in particular has played a foundational role in guiding ethical behaviour, promoting compassion, and encouraging social harmony. Yet Sri Lanka’s modern political history clearly shows that when religion becomes closely entangled with state power, both democracy and religion suffer. The politicisation of religion especially Buddhism has repeatedly contributed to ethnic division, weakened governance, and the erosion of moral authority. For these reasons, the separation of religion and the state is not only desirable but necessary for Sri Lanka’s long-term stability and democratic progress.

Sri Lanka’s post-independence political history provides early evidence of how religion became a political tool. The 1956 election, which brought S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike to power, is often remembered as a turning point where Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism was actively mobilised for political expedience. Buddhist monks played a visible role in political campaigning, framing political change as a religious and cultural revival. While this movement empowered the Sinhala-Buddhist majority, it also laid the foundation for ethnic exclusion, particularly through policies such as the “Sinhala Only Act.” Though framed as protecting national identity, these policies marginalised Tamil-speaking communities and contributed significantly to ethnic tensions that later escalated into civil conflict. This period demonstrates how religious symbolism, when fused with state power, can undermine social cohesion rather than strengthen it.

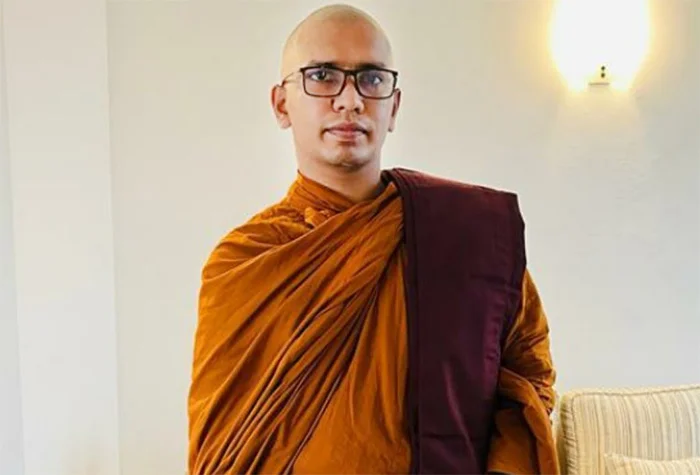

The increasing political involvement of Buddhist monks in later decades further illustrates the risks of this entanglement. In the early 2000s, the emergence of monk-led political parties such as the Jathika Hela Urumaya (JHU) marked a new phase in Sri Lankan politics. For the first time, monks entered Parliament as elected lawmakers, directly participating in legislation and governance. While their presence was justified as a moral corrective to corrupt politics, in practice it blurred the boundary between spiritual leadership and political power. Once monks became part of parliamentary debates, policy compromises, and political rivalries, they were no longer perceived as neutral moral guides. Instead, they became political actors subject to criticism, controversy, and public mistrust. This shift significantly weakened the traditional reverence associated with the Sangha.

Sri Lankan political history also shows how religion has been repeatedly used by political leaders to legitimise authority during times of crisis. Successive governments have sought the public endorsement of influential monks to strengthen their political image, particularly during elections or moments of instability. During the war, religious rhetoric was often used to frame the conflict in moral or civilisational terms, leaving little room for nuanced political solutions or reconciliation. This approach may have strengthened short-term political support, but it also deepened ethnic polarisation and made post-war reconciliation more difficult. The long-term consequences of this strategy are still visible in unresolved ethnic grievances and fragile national unity.

Another important historical example is the post-war period after 2009. Despite the conclusion of the war, Sri Lanka failed to achieve meaningful reconciliation or strong democratic reform. Instead, religious nationalism gained renewed political influence, often used to silence dissent and justify authoritarian governance. Smaller population groups such as Muslims and Christians in particular experienced growing insecurity as extremist groups operated with perceived political protection. The state’s failure to maintain religious neutrality during this period weakened public trust and damaged Sri Lanka’s international reputation. These developments show that privileging one religion in state power does not lead to stability or moral governance; rather, it creates fear, exclusion, and institutional decay.

The moral authority of religion itself has also suffered as a result of political entanglement. Traditionally, Buddhist monks were respected for their distance from worldly power, allowing them to speak truth to rulers without fear or favour. However, when monks publicly defend controversial political decisions, support corrupt leaders, or engage in aggressive nationalist rhetoric, they risk losing this moral independence. Sri Lankan political history demonstrates that once religious figures are seen as aligned with political power, public criticism of politicians easily extends to religion itself. This has contributed to growing disillusionment among younger generations, many of whom now view religious institutions as extensions of political authority rather than sources of ethical guidance.

The teachings of the Buddha offer a clear contrast to this historical trend. The Buddha advised rulers on ethical governance but never sought political authority or state power. His independence allowed him to critique injustice and moral failure without compromise. Sri Lanka’s political experience shows that abandoning this principle has harmed both religion and governance. When monks act as political agents, they lose the freedom to challenge power, and religion becomes vulnerable to political failure and public resentment.

Sri Lanka’s multi-religious social structure nurtures divisive, if not separatist, sentiments. While Buddhism holds a special historical place, the modern state governs citizens of many faiths. Political history shows that when the state appears aligned with one religion, minority communities feel excluded, regardless of constitutional guarantees. This sense of exclusion has repeatedly weakened national unity and contributed to long-term conflict. A secular state does not reject religion; rather, it protects all religions by maintaining neutrality and ensuring equal citizenship.

Sri Lankan political history clearly demonstrates that the fusion of religion and state power has not produced good governance, social harmony, or moral leadership. Instead, it has intensified ethnic divisions, weakened democratic institutions, and damaged the spiritual credibility of religion itself. Separating religion from the state is not an attack on Buddhism or Sri Lankan tradition. On the contrary, it is a necessary step to preserve the dignity of religion and strengthen democratic governance. By maintaining a clear boundary between spiritual authority and political power, Sri Lanka can move toward a more inclusive, stable, and just society one where religion remains a source of moral wisdom rather than a tool of political control.

In present-day Sri Lanka, the dangers of mixing religion with state power are more visible than ever. Despite decades of experience showing the negative consequences of politicised religion, religious authority continues to be invoked to justify political decisions, silence criticism, and legitimise those in power. During recent economic and political crises, political leaders have frequently appeared alongside prominent religious figures to project moral legitimacy, even when governance failures, corruption, and mismanagement were evident. This pattern reflects a continued reliance on religious symbolism to mask political weakness rather than a genuine commitment to ethical governance.

The 2022 economic collapse offers a powerful contemporary example. As ordinary citizens faced shortages of fuel, food, and medicine, public anger was directed toward political leadership and state institutions. However, instead of allowing religion to act as an independent moral force that could hold power accountable, sections of the religious establishment appeared closely aligned with political elites. This alignment weakened religion’s ability to speak truthfully on behalf of the suffering population. When religion stands too close to power, it loses its capacity to challenge injustice, corruption, and abuse precisely when society needs moral leadership the most.

At the same time, younger generations in Sri Lanka are increasingly questioning both political authority and religious institutions. Many young people perceive religious leaders as participants in political power structures rather than as independent ethical voices. This growing scepticism is not a rejection of spirituality, but a response to the visible politicisation of religion. If this trend continues, Sri Lanka risks long-term damage not only to democratic trust but also to religious life itself.

The present moment therefore demands a critical reassessment. A clear separation between religion and the state would allow religious institutions to reclaim moral independence and restore public confidence. It would also strengthen democracy by ensuring that policy decisions are guided by evidence, accountability, and inclusive dialogue rather than religious pressure or nationalist rhetoric. Sri Lanka’s recent history shows that political legitimacy cannot be built on religious symbolism alone. Only transparent governance, social justice, and equal citizenship can restore stability and public trust.

Ultimately, the future of Sri Lanka depends on learning from both its past and present. Protecting religion from political misuse is not a threat to national identity; it is a necessary condition for ethical leadership, democratic renewal, and social harmony in a deeply diverse society.

by Milinda Mayadunna

Opinion

NPP’s misguided policy

Judging by some recent events, starting with the injudicious pronouncement in Jaffna by President Anura Kumara Dissanayake and subsequent statements by some senior ministers, the government tends to appease minorities at the expense of the majority. Ill-treatment of some Buddhist monks by the police continues to arouse controversy, and it looks as if the government used the police to handle matters that are best left to the judiciary. Sangadasa Akurugoda concludes his well-reasoned opinion piece “Appeasement of separatists” (The island, 13 February) as follows:

“It is unfortunate that the President of a country considers ‘national pride and patriotism’, a trait that every citizen should have, as ‘racism’. Although the President is repeating it like a mantra that he will not tolerate ‘racism’ or ‘extremism’ we have never heard him saying that he will not tolerate ‘separatism or terrorism’.”

It is hard to disagree with Akurugoda. Perhaps, the President may be excused for his reluctance to refer to terrorism as he leads a movement that unleashed terror twice, but his reluctance to condemn separatism is puzzling. Although most political commentators consider the President’s comment that ‘Buddhist go to Jaffna to spread hate’ to be callous, the head of an NGO heaped praise on the President for saying so!

As I pointed out in a previous article, puppet-masters outside seem to be pulling the strings (A puppet show? The Island, 23 January) and the President’s reluctance to condemn separatism whilst accusing Buddhists of spreading hatred by going to Jaffna makes one wonder who these puppeteers are.

Another incident that raises serious concern was reported from a Buddhist Temple in Trincomalee. The police removed a Buddha statue and allegedly assaulted Buddhist priests. Mysteriously, the police brought back the statue the following day, giving an absurd excuse; they claimed they had removed it to ensure its safety. No inquiry into police action was instituted but several Bhikkhus and dayakayas were remanded for a long period.

Having seen a front-page banner headline “Sivuru gelawenakam pahara dunna” (“We were beaten till the robes fell”) in the January 13th edition of the Sunday Divaina, I watched on YouTube the press briefing at the headquarters of the All-Ceylon Buddhist Association. I can well imagine the agony those who were remanded went through.

Ven. Balangoda Kassapa’s description of the way he and the others, held on remand, were treated raises many issues. Whether they committed a transgression should be decided by the judiciary. Given the well-known judicial dictum, ‘innocent until proven guilty’, the harassment they faced cannot be justified under any circumstances.

Ven. Kassapa exposed the high-handed actions of the police. This has come as no surprise as it is increasingly becoming apparent as they are no longer ‘Sri Lanka Police’; they have become the ‘NPP police’. This is an issue often editorially highlighted by The Island. How can one expect the police to be impartial when two key posts are held by officers brought out of retirement as a reward for canvassing for the NPP. It was surprising to learn that the suspects could not be granted bail due to objections raised by the police.

Ven. Kassapa said the head of the remand prison where he and others were held had threatened him.

However, there was a ray of hope. Those who cry out for reconciliation fail to recognise that reconciliation is a much-misused term, as some separatists masquerading as peacemakers campaign for reconciliation! They overlook the fact that it is already there as demonstrated by the behaviour of Tamil and Muslim inmates in the remand prison, where Ven. Kassapa and others were kept.

Non-Buddhist prisoners looked after the needs of the Bhikkhus though the prison chief refused even to provide meals according to Vinaya rules! In sharp contrast, during a case against a Sri Lankan Bhikkhu accused of child molestation in the UK, the presiding judge made sure the proceedings were paused for lunch at the proper time.

I have written against Bhikkhus taking to politics, but some of the issues raised by Ven. Kassapa must not be ignored. He alleges that the real reason behind the conflict was that the government was planning to allocate the land belonging to the Vihara to an Indian businessman for the construction of a hotel. This can be easily clarified by the government, provided there is no hidden agenda.

It is no secret that this government is controlled by India. Even ‘Tilvin Ayya’, who studied the module on ‘Indian Expansionism’ under Rohana Wijeweera, has mended fences with India. He led a JVP delegation to India recently. Several MoUs or pacts signed with India are kept under wraps.

Unfortunately, the government’s mishandling of this issue is being exploited by other interested parties, and this may turn out to be a far bigger problem.

It is high time the government stopped harassing the majority in the name of reconciliation, a term exploited by separatists to achieve their goals!

By Dr Upul Wijayawardhana

Opinion

The unconscionable fuel blockade of Cuba

Cuba, a firm friend in need for Sri Lanka and the world, is undergoing an unprecedented crisis, not of natural causes, but one imposed by human design. It’s being starved of energy, which is almost as essential as water and air for human survival today. A complete and total embargo of oil in today’s world can only spell fatal, existential disaster, coming on top of the US economic blockade of decades.

The UN Secretary General’s spokesman has expressed the Secretary General’s concern at the “humanitarian situation in Cuba” and warned that it could “worsen, if not collapse, if its oil needs go unmet”.

Cubans are experiencing long hours without electricity, including in its hospitals and laboratories which provided much needed medicines and vaccines for the world when they were most needed. Cuba which relies heavily on tourism has had to warn airlines that they have run out of jet-fuel and will not be able to provide refueling.

Cuba is being denied oil, because it is being ridiculously designated as a “sponsor of terrorism” posing a threat to the United States, the richest, most powerful country with the most sophisticated military in the history of the world.

On the 29th of January 2026, the President of the United States issued an executive order declaring that the policies, practices and actions of the Cuban Government pose an “unusual and extraordinary threat… to the national security and foreign policy of the United States” and that there is “national emergency with respect to that threat”, and formally imposed what the Russian Foreign Ministry called an “energy blockade” on Cuba.

Responding within days to the US President’s executive order seeking to prevent the provision of oil to Cuba from any country, the Independent Experts of the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) strongly condemned the act stating that “the fuel blockade on Cuba is a serious violation of international law and a grave threat to a democratic and equitable international order,” and that it is “an extreme form of unilateral economic coercion with extraterritorial effects, through which the United States seeks to exert coercion on the sovereign state of Cuba and compel other sovereign third States to alter their lawful commercial relations, under threat of punitive trade measures”.

They warn that the resulting shortages “may amount to the collective punishment of civilians, raising serious concerns under international human rights law”. They advocate against the “normalization of unilateral economic coercion” which undermines the international legal order and the multilateral institutions.

https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2026/02/un-experts-condemn-us-executive-order-imposing-fuel-blockade-cuba

Global Concern – Will Colombo add its voice?

The Group of G77 and China which has 134 countries issued a special communique in New York stating that “these measures are contrary to the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations and international law, and undermine multilateralism, international economic cooperation and the rules-based, non-discriminatory, open, fair and equitable multilateral trading system with the World Trade Organization at its core.”

The Non-Aligned Movement also issued a communique expressing its “deep concern” at the “new extreme measures aimed at further tightening the economic, commercial and financial embargo imposed against the Republic of Cuba, including actions intended to obstruct the supply of oil to the country and to sanction third States that maintain legitimate commercial relations with Cuba.”

Sri Lanka is a member of both these groups. These two statements also speak for the Sri Lankan state, as well as all other members of these groups.

However, there has been no statement so far from Colombo expressing concern. One hopes that there will be one soon. One also hopes that this administration’s rightward turn in economics doesn’t also extend to abandoning all sense of decency towards those friends who stood by Sri Lanka when it needed them. This would not bode well for us, when we need help from our friends again.

The Sri Lankan parliament has a Cuba-Sri Lanka Friendship Association. Its President is Minister Sunil Kumara Gamage who was elected to this position for the Tenth Parliament. I hope the parliamentary friendship extends to at least expressing concern and solidarity with the Cuban people and an appeal for the immediate end to this extreme measure which has had such distressing impact on Cuba and its people.

Countries like Vietnam, Russia, China, Namibia and South Africa have already issued statements.

South Africa’s ruling African National Congress (ANC) has issued its own statement, strongly condemning this measure, calling it a “direct assault on the Cuban people” and a “deliberate economic sabotage and strangulation”. They call for “the immediate lifting of the fuel blockade and the trade embargo” calling on “the progressive forces and countries of the world, committed to progressive internationalism, peace, and prosperity, to join the ANC in solidarity against imperialist and colonialist aggression and to take further concrete actions in solidarity with Cuba.”

Before the JVP revealed itself in power to have metamorphosed into something other than its self-description before it was elected to government, with ubiquitous Che Guevara images and quotes at its rallies and party conventions, one would have expected something at least half-way as supportive from it. However, with new glimpses and insights into its trajectory in its current incarnation, one doesn’t really know the contours of its foreign policy aspirations, preferences and fears, which have caused an about-turn in all their previous pronouncements and predilections.

On a recent TV interview, a former Foreign Secretary and Ambassador/PR of Sri Lanka to the UN in New York praised the current President’s foreign policy speech, citing its lack of ideology, non-commitment to concepts such as “non-alignment” or “neutrality” and its rejection of ‘balancing’ as beneficial to Sri Lanka’s “national interest” which he went on to define open-endedly and vaguely as “what the Sri Lankan people expect”.

While this statement captures the unprecedented opacity and indeterminate nature of the President’s foreign policy stance, it is difficult to predict what this administration stands for, supports and thinks is best for our country, the world and our region.

Despite this extreme flexibility the administration has given itself, one still hopes that a statement of concern and an appeal for a reversal of the harsh measures imposed on a friendly country and long term ally at the receiving end of a foreign executive order that violates international law, could surely be accommodated within the new, indeterminate, non-template.

FSP, Socialist Alliance stay true

Issuing a statement on February 1st, the Frontline Socialist Party (FSP), the JVP breakaway, was the first to condemn and denounce the new escalation. It said in its statement that this “decision which seeks to criminalize and punish sovereign states for engaging in lawful trade with Cuba -particularly in relation to fuel supplies- represents an act of economic warfare and blatant imperialist coercion.” The FSP urged all progressive movements to “raise their voices against this criminal blockade and reject the normalization of economic aggression and collective punishment.”

The Executive Committee of the Socialist Alliance of Sri Lanka comprising the Communist Party of Sri Lanka, Lanka Sama Samaja Party, Democratic Left Front and Sri Lanka Mahajana Party, wasted no time in condemning what it called the “escalation of the decades-long criminal blockade” against Cuba by the United States. It said that the energy embargo has transformed “an inhuman blockade into a total siege” which it says seeks to “provoke economic collapse and forcible regime change”.

https://island.lk/socialist-alliance-calls-on-govt-to-take-immediate-and-principled-action-in-defence-of-cuba

In its strongly worded message issued by its General Secretary, Dr. G. Weerasinghe, the alliance calls on the government to demonstrate “principled courage” and to publicly condemn the “economic siege” at all international forums including the UN. It also asks the government to co-sponsor the UNGA resolution demanding an end to the US blockade, which seems unlikely at this stage of the administration’s rightward evolution.

The Socialist Alliance concludes by saying that “Silence in the face of such blatant coercion is complicity” and that this “imperialist strategy” threatens the sovereignty of all independent nations. However prescient these words may be, the government has yet to prove that terms such as “sovereignty” and “independence” are a relevant part of its present-day lexicon.

Cuba Flotilla

The plight of the people of Cuba under the energy blockade has moved those inspired by the Global Sumud Flotilla which sailed to Palestine with aid, to initiate a similar humanitarian project for Cuba. An alliance of progressive groups has announced their intention to sail to Cuba next month carrying aid for Cubans. It is called the “Nuestra América Flotilla” (https://nuestraamericaflotilla.org/).

While Mexico and China have already sent aid, the organisers recognise the need for more. David Adler, who helped organise the Sumud Flotilla is also helping the Cuba flotilla. This effort has been endorsed by the Brazilian activist who came into prominence and gained global popularity during the Sumud flotilla, Thiago Avila.

The organizers hope that this month’s successful Mexican and Chinese aid deliveries to Cuba may indicate that unlike in the case of the Sumud Flotilla to Occupied Palestine, the aid flotilla to Cuba will reach the people of Cuba without interception.

Shape of the emerging world order

At the on-going Munich Security Conference, the German Chancellor announced that the Rules-Based-Order has ended. With Europe dealing with the real threat of the forcible annexation of Greenland by the United State, their longtime ally, it is no wonder that he declared the end of the old order.

At the same venue, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC), Congresswoman representing New York, questioned whether the Rules-Based-Order ever existed, when the rules seem to apply only to some. Characteristically clear-sighted and forthright, the progressive US Democrat said exceptions to the rules were carved out in the world to suit the US and when that happens too often, those exceptions become the rule. She asked if we have actually been living in a “pre-Rules Based Order”, rather than one that had already been established.

Regarding the January oil blockade of Cuba, AOC issued a statement saying that the world is entering an “era of depravity”.

The UN has long advocated against Unilateral Coercive Action, which threatens countries with trade sanctions, financial restrictions, asset freezes and blockades without authorization by the United Nations system. These have also been referred to as “private justice”, which brings home the chilling nature of these measures.

Are these ruptures with even the bare minimum of predictable behaviour in international relations, the birth-pangs of a new era emerging in a world almost incomprehensible in its behaviour towards states and peoples, starting with the genocide in Occupied Palestine? The nightmares have not yet reached their peak, only signaled their downward spiral. With enormous US aircraft carriers circling Iran, what would the fate of that country and the region and perhaps the world be, in a few weeks?

Cuba is under siege right at this moment of danger. An exemplary country which helped the world when it faced grave danger such as the time of Covid 19, Cuba and the selfless Cuban people are now in dire need.

Cuba has never hesitated to help Sri Lanka, and could be relied on unconditionally for support and solidarity at multilateral forums. Sri Lankan medical students have had the benefit of training in Cuba and Cuban medicines and vaccines have served the world, as have their doctors. And now, as Cuban Ambassador Maria del Carmen Herrera Caseiro, who as a skillful young diplomat in Geneva in 2007-2009 was helpful to Sri Lanka’s successful fightback at the UNHRC, said at the UNESCO this month, the new blockade will “directly impact Cuban education, science and the communication sectors”.

Sri Lanka has consistently voted against the decades-long economic blockade of Cuba by the United States, whichever administration was in power. This recent escalation to a full embargo of fuel supplies to this small island struggling against an already severe economic blockade, requires a response from all those who have benefited from its generosity including Colombo, and every effort to prevent a humanitarian crisis on that island.

[Sanja de Silva Jayatilleka is author of ‘Mission Impossible Geneva: Sri Lanka’s Counter-Hegemonic Asymmetric Diplomacy at the UN Human Rights Council’, Vijitha Yapa, Colombo 2017.]

Sanja de Silva Jayatilleka

-

Life style4 days ago

Life style4 days agoMarriot new GM Suranga

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoMonks’ march, in America and Sri Lanka

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoThe Rise of Takaichi

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoWetlands of Sri Lanka:

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoThailand to recruit 10,000 Lankans under new labour pact

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoMassive Sangha confab to address alleged injustices against monks

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoIMF MD here