Opinion

Towards a more profitable and sustainable agriculture

One of the key happenings in human history, is the so-called “Industrial Revolution,” that originated about two centuries ago, (principally in Europe, North America and Japan), as the focal points. These are now broadly defined as “Developed Countries.” They distinguish themselves as having higher per capita incomes, and thereby offering their citizens better living conditions than do the “Developing” or “Less developed” ones.

It is tempting yet erroneous, to believe that what prevailed two centuries ago, can be transposed today to other countries including Sri Lanka, presently classified among the “Developing Countries.”

Typically, the industrial era manifested as a movement away from farming and towards machinery driven enterprises. The unspoken corollary is that what worked for them then, should do for us now.

This is a presumption that is unlikely to happen. Although a small tropical country within the Monsoon belt, we are fortunate in being spared weather-related atmospheric perturbations such as hurricanes, cyclones and tsunamis, that assail other similar countries and locations.

Overall, we are fortunately blessed with largely favourable climatic conditions and reasonably fertile soils, to ably support a sustainable, diversified and a seemingly unique mosaic of farming, livestock and forestry. This is worthy of protection.

By virtue of our geography, climate, tradition and aptitude, we are well positioned to be a dominant base for a vibrant Agrarian Economy.

A composite of the sectors deriving from plants and animals, best suits our natural strengths. This leads us logically to seek economic advancement through this sector, with a blend of farming, livestock and forestry, to best support environmental stability as our long-term goal.

Two factors that are poised to impact on Worldwide agriculture, are “global warming” and a looming water crisis. These will affect different regions with differing severity. This has aroused much international concern. Sri Lanka would do well to prepare itself for this eventuality.

In the particular context of Sri Lanka, the priority considerations in the agricultural sector, calling for close and timely attention are as follows:

(i) Correcting weaknesses in the Extension Services which are primarily blamed for under- performance. All officers concerned, would benefit from periodic exposure to training that is designed for upgrading knowledge and sharpening requisite skills.

(ii) The Sri Lankan Agricultural Sector divides into two components, –namely, the Export and Local Crop sectors. Animal farming is set apart, and historically has received less attention. However, the recently expanding poultry industry, has resulted in greater attention to livestock expansion.

(iii) In Ceylon’s colonial history, it was the British, who exercised their sovereignty over the whole island, succeeding the Portuguese and Dutch, who were confined to the coastal regions. Cinnamon was the first crop that attracted the colonizers, this was followed sequentially by Cinchona (Pyrethrum, on a small scale) and Coffee. In the 1840’s, the invasion by the Coffee Rust (Hemileia vastatrix) laid waste the Coffee plantations. Tea took over and rapidly expanded, mainly by encroaching into Highland Forest areas. Little attention was given to environmental and social consequences. Meantime, Rubber plantations dominated in the wetter Lowlands. A while later, attention was directed towards coconut.

Research Institutes – TRI, RRI and CRI were established to cater to the needs of the fast-developing Plantation Crops.

The introduction of Plantation Crops had far-reaching and lasting Economic, Political, Social, Environmental and Cultural consequences. The recently established Minor Export Crops, mainly serviced the Spice Crops Cinnamon, pepper, Nutmeg and Cardamom. Also, Cocoa and Coffee. Sugar, Cashew and Palmyra are crops that are developing their own support structures.

All others are catered for by the Department of Agriculture, whose main efforts are focused on the Paddy sector. This is a sector that had received scant attention from the colonial British, who had an understandable preference for importation of rice from colonial Burma and Thailand.

(v) This cleavage (into export and local sectors), while having several operational advantages, also created problems. These include social and citizenship complexities, arising from the large importation of labour from South India, to develop the rapidly increasing new plantation areas. The early tea estates were in the Central Hills, and also resulted in widespread expropriation of private and peasant- owned lands. This is still a silent concern.

(v) Since it is impossible to balance the requirements and production of agricultural produce, scarcities and gluts are not uncommon. Scarcities are met by imports, while surpluses largely result in wastage. This can be as high as 35% in the case of perishable vegetables and fruits. To deal with such surpluses, obvious remedies include providing better storage facilities with protection from insects, fungi, rodents and other marauders. Such storage could suit Paddy, maize, pulses, peanuts and some fruits.

In the case of vegetables, much fruit and other perishable produce,

post-harvest handling and transport are key needs.

Where appropriate, preservation by simply drying (by Sun, ovens or other equipment), freezing, canning, bottling and packaging are means of coping with surpluses and in most cases, also as a means of value addition.

These are the considerations paramount in developing a profitable and sustainable Agriculture – which will continue to play a key role in the National Economy.

Dr. Upatissa Pethiyagoda

Opinion

Emerging narrative of division: Intellectual critique of NPP following presidential appointment

In the wake of Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s appointment as President, an unsettling narrative has emerged from a small but vocal group of intellectuals within the Sri Lankan society. This faction seems intent on portraying the National People’s Power (NPP) as a social entity burdened with history of violence, a portrayal that is not only misleading but also dangerous in its potential repercussions for national unity.

The intellectual critique in question often draws upon past events from Sri Lanka’s turbulent history—specifically the insurrections of 1971 and 1988. These events, which were marked by political unrest and significant bloodshed, are being referred to create a negative image of the NPP, depicting it as an organisation with a legacy of violence.

While these incidents undoubtedly left deep scars on the national psyche, the selective emphasis on these periods, while glossing over other equally important historical contexts, is concerning. Most notably, the narrative ignores the three-decade-long terrorism perpetuated by the LTTE, which claimed thousands of lives and posed an existential threat to the country’s sovereignty. This omission, whether deliberate or inadvertent, raises questions about the motives behind such critiques.

Interestingly, this narrative is not confined to private intellectual circles. It has found its way into the mainstream media, including television programmes where a small section of the elite has voiced these concerns. Their views, though presented under the guise of objective analysis, appear to be rooted in specific historical grievances rather than a balanced understanding of the NPP’s present-day policies and leadership.

The portrayal of the NPP as a violent faction is not only misleading but also problematic for the broader national discourse. By continuously referring to past insurrections without addressing the socio-political context in which the NPP operates today, these intellectuals risk fostering division, rather than promoting constructive dialogue about the country’s future.

What is particularly troubling is the potential impact of these narratives on the minds of the innocent populations in the North and East of Sri Lanka. These regions, already burdened by decades of conflict, are especially vulnerable to manipulations of historical narratives. The attempt to seed fear and distrust through selective memories of the past could widen ethnic and political divides, reversing the hard-won progress made in reconciliation and peacebuilding efforts.

The implications of these actions are profound. If left unchecked, this manipulation of historical facts could fuel distrust, especially in communities that are still healing from the traumas of war. Such divisive rhetoric, which paints certain political movements in broad, negative strokes, undermines efforts to foster national unity, which is critical at this juncture in Sri Lanka’s development.

It is imperative that both the government and the informed public remain vigilant in the face of these developments. While free speech and intellectual discourse are essential in any democracy, the dissemination of false or misleading information must be addressed with caution. The current administration, along with media outlets and thought leaders, must prioritise the accurate representation of political parties and movements, ensuring that all voices are heard in an atmosphere of respect and truth.

Furthermore, the intellectual elite must recognise their responsibility in shaping public opinion. Rather than perpetuating narratives rooted in selective memory and old political rivalries, they should engage in constructive dialogue about how Sri Lanka can move forward—socially, politically, and economically. Only by acknowledging the complexities of the past and focusing on the present can the country achieve the progress and development it desperately needs.

In conclusion, the emerging portrayal of the NPP as a faction tainted by historical violence is a dangerous oversimplification of a more complex reality. It is crucial that all stakeholders, from the government to the intellectual elite, approach political discourse with a sense of responsibility and an eye toward the future. Only then can Sri Lanka continue its path toward reconciliation, unity, and sustainable development.

K R Pushparanjan

Canada

Opinion

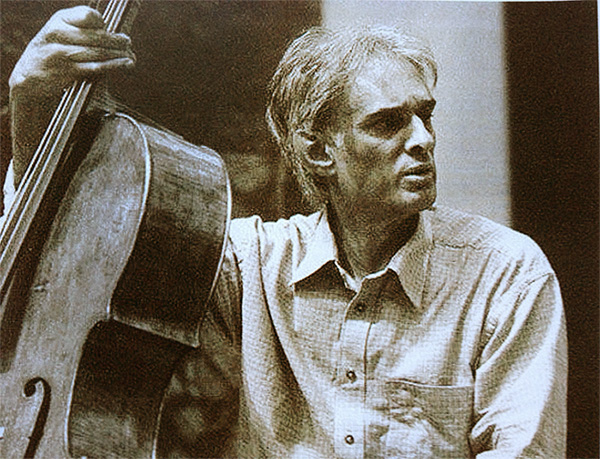

The passing away of a great cellist

by Satyajith Andradi

The Oxford Dictionary of Music compiled by Michael Kennedy is an invaluable source of reference material on the whole gamut of western classical music. Its 1994 second edition has the following entry on Rohan De Saram, in its usual telegraphic language : “De Saram, Rohan ( b Sheffield, 1939 ). Sri Lankan cellist. Studied in Florence with Cassado and later with Casals in Puerto Rico. After European recitals made Amer. Debut in NY, 1960. Settled in Eng. 1972, joining teaching staff of TCL. Wide repertory from Haydn to Xenakis, specializing in contemp. works. Cellist of *Arditti String Quartet.” Rohan De Saram is certainly one of the greatest musicians Sri Lanka has ever produced. He passed away in the UK on 29th September 2024 at the age of 85.

I had the good fortune to see this great musician perform in two occasions. The first was way back in 1975, when my parents took me to see his cello recital, which was given at the newly opened BMICH on 16th August that year. The second was when I took my daughter to his concert at the British Council auditorium on 27th February 2007. There was a marked difference in the type of music he performed at the two recitals. The 1975 programme was dominated by the music of Rachmaninov, Schubert, and Shostakovich, with the first movement of Zoltan Kodaly’s Sonata for Solo Cello added as a sort of outlier. It belonged to the traditional western music repertoire, if you like. In contrast, the 2007 concert was dominated by more contemporary music, although it included pieces by Bach, Beethoven, Rimsky Korsakov, Gabriel Faure, Saint Sean, and Benjamin Britten. The highlights of the evening were Luciano Berio’s Sequenza 14 for solo cello, a through and through avant garde work, and the last two movements of Kodaly’s Sonata for Solo Cello. Needless to say, the two programmes reflected the tremendous change in Rohan De Saram’s artistic orientation from being a performer of classics to that of avant garde music by composers such as Iannis Xenakis and Luciano Berio.

Rohan De Saram was born in the UK on 9th March 1939. He belonged to a well-to-do cultured family. Due to the outbreak of the Second World War, he had to spend much of his early childhood in Sri Lanka. As he showed a special gift for cello playing, he was taken to Europe for his musical education. Initially he studied cello under the renowned Spanish cellist and composer Gaspar Cassado in Florence, Italy. His first appearance as a soloist at the Royal Festival Hall in London was at the age of sixteen. This was followed by performances as soloist at London’s Wigmore Hall and Royal Albert Hall. Winning the Guilhermina Suggia award, enabled him to take master classes from the great Spanish cellist and composer Pablo Casals, who wrote of him: “There are few of his generation who have such gifts” and ” Rohan is already a remarkable cellist of fine technique and musical taste. I can predict for him a brilliant career.”

Casals’ prophesies were to come true. Rohan De Saram had his Carnegie Hall debut at the age of 20. He went on to perform as a soloist with many of the world’s leading orchestras such as the London Symphony Orchestra, the London Philharmonic Orchestra, the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra under the leadership of renowned conductors such as Adrian Boult, Malcolm Sargent, John Barbirolli, Colin Davis, and Zubin Mehta. During this early period of his career, he was essentially a virtuoso performer of the classics. However, joining the Arditti Quartet in he late 70s as its cellist signaled a turning point in his musical orientations. This quartet specialized in contemporary avant garde music. Henceforth, the main focus of Rohan De saram was on the works of avant garde composers such as Iannis Xenakis and Luciano Berio. He was a member of the Arditti Quartet from 1979 to 2005. As a virtuoso cellist of international renown, he introduced contemporary music to numerous musical audiences throughout the world. His passing away leaves a void in the musical firmament.

Opinion

UK’s deal with Mauritius will be a win for all

Freedom for Chagos islands:

by Peter Harris

Associate Professor of Political Science,

Colorado State University

Britain is close to resolving its territorial dispute with Mauritius over the Chagos Archipelago, located in the central Indian Ocean.

For years, Mauritius has claimed the island group as part of its sovereign territory. It says that Britain unlawfully detached the islands from Mauritius in 1965, three years before Mauritius gained independence. The Mauritian position is backed by international courts and the United Nations, creating enormous pressure for Britain to decolonise.

London, however, has been reluctant to abandon the Chagos Archipelago. This is because the largest island, Diego Garcia, is the site of a strategically important US military base. Britain pledged to make Diego Garcia available to its American ally and has been anxious to avoid a situation where it is prevented from making good on these promises.

The US, for its part, has declined to become publicly involved in the dispute. Its private position is merely that the base on Diego Garcia should not be placed in jeopardy.

In a deal announced in a joint statement, London and Port Louis have agreed that all but one of the Chagos Islands will be returned to Mauritian control as soon as a treaty can be finalised. This comes after nearly two years of intense negotiations. It seems as though settling the dispute was a top priority for Britian’s new Labour government.

Though the deal isn’t done yet, it is expected to go through. Both Britain and Mauritius, along with the White House, have endorsed the agreement, indicating that the toughest negotiations are complete.

Diego Garcia will remain under British administration for at least 99 years – this time with the blessing of Mauritius – enabling Britain to continue furnishing the US with unfettered access to its military base on the island.

In exchange for permission to continue on Diego Garcia, Britain will provide “a package of financial support” to Mauritius. The exact sums of money have not been disclosed but will include an annual payment from London to Port Louis. Both sides will cooperate on environmental conservation, issues relating to maritime security, and the welfare of the indigenous Chagossian people – including the limited resettlement of Chagossians onto the outer Chagos Islands under Mauritian supervision.

I’ve studied the Chagos Islands for 15 years, first as a master’s student and now as a professor. It often looked as though this day would never come.

The deal that’s been announced is a good one – a rare “win-win-win-win” moment in international relations, with all the relevant actors able to claim a meaningful victory: Britain, Mauritius, the US, and the Chagossians.

Win for Britain

Britain went into these negotiations with one goal in mind: to bring itself into alignment with international law.

London suffered humiliating setbacks at the permanent court of arbitration in 2015, concerning the legality of its Chagos marine protected area; at the International Court of Justice in 2019, when the World Court found that Mauritius was sovereign over the archipelago; and at the UN general assembly that same year, when a whopping 116 governments called on Britain to exit the Chagos Islands.

Mauritian sovereignty over the Chagos group had even begun to be inscribed into international case law.

London could probably have defied international opinion if it had wanted to. Nobody would have forced Britain to halt its illegal occupation of the Chagos Archipelago. But such a course would have badly undermined Britain’s global reputation and its ability to criticise others for breaches of international law.

This agreement will give Britain exactly what it wanted: a continued presence on Diego Garcia that conforms with international law.

Win for Mauritius

Mauritius, of course, went into these negotiations intent on securing full decolonisation at long last. Britain and the US now recognise that the Chagos Archipelago belongs to Mauritius.

Mauritius will not have day-to-day control of Diego Garcia, but it will be acknowledged as being sovereign there. The public description of the agreement also doesn’t seem to prohibit Mauritius from exercising its sovereignty over Diego Garcia as it relates to non-military domains.

Win for the US

The US is another clear winner from the deal. In fact, hardly anything will change for America. Washington will continue working closely with London, and will not need to negotiate an agreement with Mauritius on its rights to the base or the status of forces.

Indeed, Pentagon officials should be thrilled that their base on Diego Garcia has been put on firm legal footing. This is something that Britain alone was unable to offer. The bilateral agreement with Mauritius will ensure the security of the base for 99 years – no small feat.

Good for Chagos Islanders

Finally, the deal is good for the Chagos Islanders.

British agents forcibly depopulated the entire Chagos group between 1965 and 1973. The point was to rid the archipelago of its permanent population so that the US base on Diego Garcia would operate far from prying eyes. Britain deported the Chagossians to Mauritius and the Seychelles, which is where most Chagossians and their descendants still live. Some have migrated onwards, including to Britain.

Britain had long opposed the resettlement of the Chagos group by the exiled Chagossians. Mauritius, on the other hand, has indicated its openness to resettlement of the Outer Chagos Islands – so, not Diego Garcia – something that Port Louis is now free to pursue.

Not all islanders have welcomed news of an agreement. The Chagossians are a large and diverse group, with differing views about how their homeland should be governed. Some would have preferred Britain to administer the entire archipelago long into the future, feeling that Mauritius was an unwelcoming host to the exiled Chagossians. But Britain could not hold onto the Chagos Islands forever – at least, not lawfully.

For their part, the largest Chagossian organisations are content with the deal as it has been announced, and will now work with Mauritius on a resettlement plan.

The critics

This is the first instance of decolonisation that London has attempted since returning Hong Kong to China in 1997. Predictably, some in Britain are opposed to the settlement.

Some accuse the Keith Starmer government of “giving up” the Chagos Archipelago. But the islands were never Britain’s to give up – they were always Mauritian sovereign territory, and Britain was an unlawful occupier.

They are also wrong to blame this deal for jeopardising the base on Diego Garcia. The opposite is true: for better or worse, the agreement will resolve any uncertainty about the US base’s future. It will have total legal security.

Finally, critics are grasping at straws when they raise the prospect of Mauritius permitting a Chinese base in the Chagos Archipelago. This is a baseless smear. There is no indication whatsoever that Port Louis has any interest in hosting the Chinese military.

What happens now?

Britain and Mauritius still need to reveal the text of their bilateral treaty. But the deal is highly unlikely to fall through. Both governments, plus the White House, have welcomed the agreement – a sure sign that the hard work of negotiations is over.

All that remains is for the treaty to be ratified – a process that does not require a parliamentary vote in the House of Commons. There is no reason why this cannot be done quickly.

This could be the end of a shameful saga that went on for too long.

(Courtesy of The Conversation.)

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoSajith top presidential election spender

-

Latest News7 days ago

Latest News7 days ago“Ensure the continuity of the public service without disruption” – President

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoSri Lanka Tourism surpasses 2023 tourist arrivals

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoSJB-UNP alliance talks break down due to senior UNPer’s intervention – SJB Chairman

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoThe Economy, Executive Presidency, and the Parliamentary Election

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoThrowing ministers behind bars

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoAbheeth takes five but St. Anthony’s ahead

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoRajeev Amarasuriya to run for BASL President 2025/26