Features

The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida: a Failed Novel about a Failed People

By Dhanuka Bandara

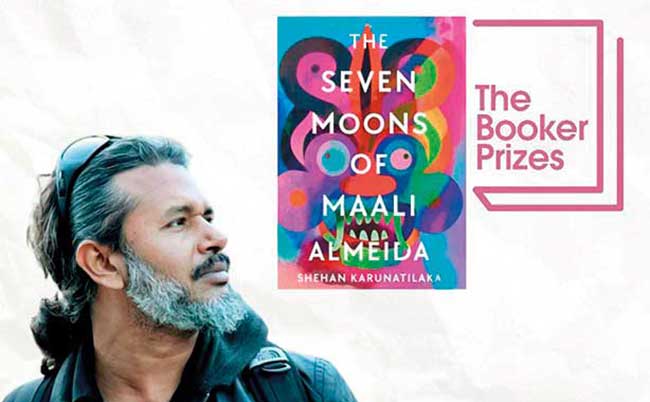

Shehan Karunatilaka’s first novel, Chinaman: The Legend of Pradeep Matthew won immediate critical and public acclaim upon its publication in 2010. The manuscript of the novel had already won the Gratiaen Prize and there was some buzz about it in the Sri Lankan critical circles even before the novel’s publication. It certainly did not disappoint, in fact it over-delivered. I remember many who thought that it was the “Great Sri Lankan Novel” and maybe it is. Chinaman went on to gain international recognition, including the Commonwealth Book Prize (2012). Unlike Karunatilaka’s first novel, his second, the Booker Prize winning, The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida, was first acclaimed in the West. Before it won the Booker Prize hardly anyone had read it in Sri Lanka and the book was known in a different, earlier version, Chats with the Dead.

I first heard about Karunatilaka’s great triumph on BBC. It is the first time a Sri Lankan had won the Booker Prize, excluding Michael Ondaatje whose Sri Lankan connection is pretty tenuous. From the get go I had an uneasy feeling about this novel. I heard that it was about the murder of a Sri Lankan, queer, war photographer in the 80s. It seemed to me that Karunatilaka was trying to hit all the right tropes to write the kind of postcolonial novel that the West found agreeable to their woke tastes. Karunatilaka received his precious prize from the Queen Consort, Camilla Parker who, to the best of my knowledge, has never really shown any real interest in literary endeavors, at a glitzy event whose “celebrity guest” was Dua Lipa, whose connection with the literary world is also not clear. Couple of weeks later I bought a copy of the book and started reading it, expecting it to be average at best, and found it to be an unmitigated failure as a novel in every imaginable respect; stylistically, ideologically and otherwise.

I know that there are many in Sri Lanka who have similar sentiments about the book and most of them are not willing to share them in public lest they are called, right-wing nationalists, Sinhala Buddhist chauvinists, jingoists, homophobes or worse. There is this pervasive pressure to claim that one likes the book, especially given that it comes with the approval of the supposedly erudite western critics, who know what they are doing, and the novel also seemingly espouses a political ideology that is deemed desirable in “polite” liberal circles in Colombo, Sri Lanka and elsewhere. Nevertheless, needless to say, that it is important that we have an honest, and measured critical discussion about our first Booker Prize winning novel. Whether you like it or not, its historical significance is indubitable.

How did then a novel, that in my view, is a complete failure win the prestigious Booker Prize that the absolute greats of twentieth century writing had won in the past? Karunatilaka’s book confirms everything that the West has learnt about Sri Lanka in the last couple of decades; that we are a stupid, racist, sexist, homophobic people who have entirely f—ed up. Ironically enough, this is not altogether untrue. Hence the title of this piece. The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida is a failed novel about a failed people. The failure of the book reflects our own failure. However, I found that it is repugnant to exploit the misery—self-inflicted or otherwise—of one’s own people to win accolades from the West, who in no small measure is also responsible for the mess that Sri Lanka (and the “Third World” in general) is today.

The novel opens with the dead protagonist waking up in what appears to be purgatory, or perhaps it could be better understood as “gandhabba avadiya”—an in between space where he is given “seven moons” to find out who killed him and a stash of hidden photographs of great consequence. The opening is tangibly Dantesque and Maali Almeida meets Dr. Ranee Sridharan—no doubt a fictional rendition of Rajani Thiranagama—who sort of plays Virgil to Almeida’s Dante. She appears to be some kind of gate-keeper in the afterworld. The fictionalization of Rajani Thirangama in this way seems rather distasteful, a questionable narrative choice, and rather platitudinous at that; an attempt at appealing to the NGO crowd that romanticize and venerate Rajani Thiranagama and her legacy, albeit without an iota of her courage and conviction.

This is not to diminish Rajani Thiranagama’s significance as an activist, and her death which has accorded her the status of martyrdom; rather it is Karunatilaka’s frivolous and unskilled treatment of her that I find, well, almost disrespectful. For example, look at the following section where Dr. Ranee tells the protagonist about her husband and family: “He supported me though he didn’t agree with me. He stopped all politics after I died. He’s Down There. Looking after my girls. He’s a lovely father. And I visit him in dreams and tell him whenever I can.” This kind of writing is corny, to say the least.

Karunatilaka glibly oversimplifies the Sri Lankan ethnic conflict and the youth insurrection in the 80s. The overall point appears to be as Sri Lankans we just like to murder each other. For example look at the following descriptions of abbreviations which are clearly included in the novel to make life easier for the western readership:

LTTE – The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam

· Want a separate Tamil state

· Prepared to slaughter Tamil civilians and moderates to achieve this.

JVP – The Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna

· Want to overthrow the capitalist state

· Are willing to murder the working class while they liberate them.

UNP – The United National Party

· Known as the Uncle Nephew Party

· In power since the late ’70s and embroiled in the above two wars.

My point is not that there isn’t any truth in these claims, rather they oversimplify and particularly so for a western readership, the civil unrest in the 80s. And these oversimplifications and generalizations help establish the larger point of the novel, which is that we are a dumb and animalistic people: “If we have an animal as a national symbol, why not a pangolin, something original that we can own.

Like many Sri Lankans, pangolins have big tongues, thick hides and small brains. They pick on ants, rats and anything smaller than them. They hide in terror when faced with bullies and get up to mischief when the lights are out. They are hundreds of thousands of years old and are plodding towards extinction.” The number of “orientalist” clichés that Karunatilaka has packed into these lines is quite impressive. We (the Sri Lankans) are primarily animals. We look like animals and act like animals. We are cowardly bullies and we are headed towards extinction. We occupy a lower rung of the evolutionary hierarchy. No doubt the discerning judges of the Booker Prize paid due attention to passages such as this and it had a determining impact on their final decision.

There are many Sri Lankan novels about the political unrest since independence: When Memory Dies (A. Sivanandan), Anil’s Ghost (Michael Ondaatje) Funny Boy (Shyam Selvadurai), Reef (Romesh Gunesekera), Moonsoons and Potholes (Manuka Wijesinghe) among others. However, it is Karunatilaka who has truly managed to cash in on the misery of his own people by coming up with the right formula. All the novels mentioned above are more or less better written, better structured and have a better reading of the civil unrest that gripped the country in the 70s and 80s, and at any rate are more compelling as novels. Sivanandan’s When Memory Dies has a particularly nuanced reading of Sri Lankan politics since independence. Yet none of them met with the critical success of Maali Almeida.

Perhaps the timing was just right for Karunatilaka’s book, or perhaps it won the acclaim that it did, because its author turns the orientalist nonsense up to twelve. While on the one hand, as I have argued above, the novel oversimplifies the causes behind the violence in the 80s, and shows us as no better than animals, it endlessly indulges in exoticization. One of the novel’s striking aspects is its superficial use of Sri Lankan mythology. Terms such as preta, bodhisattva, varam and kanatte keep coming up over and over again and sometimes for no reason at all.

Consider for a moment the following sentence: “Forgotten smiles and bewildered eyes flutter in the air as the lorry turns into the kanatte” (224). Karunatilaka here appears to deliberately try to make the novel exotic and esoteric. What else could it be? After all there is a perfectly good English word for kanatte which we all know and use. Here is another example: “The man changes his shirt and walks to the bus stop. He jokes with the boy at the cigarette kade and takes the number 134 bus into Colombo.” What on earth is a “cigarette kade”? As an occasional smoker myself I know for a fact that there are no cigarette kades. There are petti kades that sell cigarettes though. If Karunatilaka’s attempt here is to add a “local flavor” to his writing—fatuous as it is—he should at least get his lingo right.

In a novel that trashes Sri Lankans for being Sri Lankan, the only characters who are portrayed in a positive light, with an ethical consciousness and as free agents are those who belong to Colombo’s liberal, English speaking upper middle-class: the protagonist himself, his lover, Dilan Dharmendran (DD) and his friend Jaki. None of these narrative choices are accidental, if anything they are clichés. The only good people in this country, and possibly elsewhere, who are not racist, sexist or homophobic are the westernized liberal middle-class. By now, I’m old enough to know that this is the sort of nonsense that gets you to places. The question then is how are we to come to terms with Maali Almeida? Our first bona fide Booker Prize winning novel.

I have been careful to point out above that, in the final analysis, what Karunatilaka is saying about Sri Lankans is not even altogether untrue. It is true that racism, sexism and our utter collective stupidity have wrecked this country. We are today a defeated, humiliated, and impotent people and many of us are struggling to leave the country altogether. Therefore, I suggest that we understand the failure of Maali Almeida as our own failure. The failure of Maali Almeida, and the failure of Shehan Karunatilaka, reflects the failure of Sri Lanka as a nation, and as a people. I think it is with the acceptance of this reality that we would be able to redeem ourselves as a people, and hopefully someday produce a decent novel or two. After all, the beginning of wisdom is the realization that one is one’s own problem.

Features

Digital transformation in the Global South

Understanding Sri Lanka through the India AI Impact Summit 2026

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has rapidly moved from being a specialised technological field into a major social force that shapes economies, cultures, governance, and everyday human life. The India AI Impact Summit 2026, held in New Delhi, symbolised a significant moment for the Global South, especially South Asia, because it demonstrated that artificial intelligence is no longer limited to advanced Western economies but can also become a development tool for emerging societies. The summit gathered governments, researchers, technology companies, and international organisations to discuss how AI can support social welfare, public services, and economic growth. Its central message was that artificial intelligence should be human centred and socially useful. Instead of focusing only on powerful computing systems, the summit emphasised affordable technologies, open collaboration, and ethical responsibility so that ordinary citizens can benefit from digital transformation. For South Asia, where large populations live in rural areas and resources are unevenly distributed, this idea is particularly important.

People friendly AI

One of the most important concepts promoted at the summit was the idea of “people friendly AI.” This means that artificial intelligence should be accessible, understandable, and helpful in daily activities. In South Asia, language diversity and economic inequality often prevent people from using advanced technology. Therefore, systems designed for local languages, and smartphones, play a crucial role. When a farmer can speak to a digital assistant in Sinhala, Tamil, or Hindi and receive advice about weather patterns or crop diseases, technology becomes practical rather than distant. Similarly, voice based interfaces allow elderly people and individuals with limited literacy to use digital services. Affordable mobile based AI tools reduce the digital divide between urban and rural populations. As a result, artificial intelligence stops being an elite instrument and becomes a social assistant that supports ordinary life.

Transformation in education sector

The influence of this transformation is visible in education. AI based learning platforms can analyse student performance and provide personalised lessons. Instead of all students following the same pace, weaker learners receive additional practice while advanced learners explore deeper material. Teachers are able to focus on mentoring and explanation rather than repetitive instruction. In many South Asian societies, including Sri Lanka, education has long depended on memorisation and private tuition classes. AI tutoring systems could reduce educational inequality by giving rural students access to learning resources, similar to those available in cities. A student who struggles with mathematics, for example, can practice step by step exercises automatically generated according to individual mistakes. This reduces pressure, improves confidence, and gradually changes the educational culture from rote learning toward understanding and problem solving.

Healthcare is another area where AI is becoming people friendly. Many rural communities face shortages of doctors and medical facilities. AI-assisted diagnostic tools can analyse symptoms, or medical images, and provide early warnings about diseases. Patients can receive preliminary advice through mobile applications, which helps them decide whether hospital visits are necessary. This reduces overcrowding in hospitals and saves travel costs. Public health authorities can also analyse large datasets to monitor disease outbreaks and allocate resources efficiently. In this way, artificial intelligence supports not only individual patients but also the entire health system.

Agriculture, which remains a primary livelihood for millions in South Asia, is also undergoing transformation. Farmers traditionally rely on seasonal experience, but climate change has made weather patterns unpredictable. AI systems that analyse rainfall data, soil conditions, and satellite images can predict crop performance and recommend irrigation schedules. Early detection of plant diseases prevents large-scale crop losses. For a small farmer, accurate information can mean the difference between profit and debt. Thus, AI directly influences economic stability at the household level.

Employment and communication reshaped

Artificial intelligence is also reshaping employment and communication. Routine clerical and repetitive tasks are increasingly automated, while demand grows for digital skills, such as data management, programming, and online services. Many young people in South Asia are beginning to participate in remote work, freelancing, and digital entrepreneurship. AI translation tools allow communication across languages, enabling businesses to reach international customers. Knowledge becomes more accessible because information can be summarised, translated, and explained instantly. This leads to a broader sociological shift: authority moves from tradition and hierarchy toward information and analytical reasoning. Individuals rely more on data when making decisions about education, finance, and career planning.

Impact on Sri Lanka

The impact on Sri Lanka is especially significant because the country shares many social and economic conditions with India and often adopts regional technological innovations. Sri Lanka has already begun integrating artificial intelligence into education, agriculture, and public administration. In schools and universities, AI learning tools may reduce the heavy dependence on private tuition and help students in rural districts receive equal academic support. In agriculture, predictive analytics can help farmers manage climate variability, improving productivity and food security. In public administration, digital systems can speed up document processing, licensing, and public service delivery. Smart transportation systems may reduce congestion in urban areas, saving time and fuel.

Economic opportunities are also expanding. Sri Lanka’s service based economy and IT outsourcing sector can benefit from increased global demand for digital skills. AI-assisted software development, data annotation, and online service platforms can create new employment pathways, especially for educated youth. Small and medium entrepreneurs can use AI tools to design products, manage finances, and market services internationally at low cost. In tourism, personalised digital assistants and recommendation systems can improve visitor experiences and help small businesses connect with travellers directly.

Digital inequality

However, the integration of artificial intelligence also raises serious concerns. Digital inequality may widen if only educated urban populations gain access to technological skills. Some routine jobs may disappear, requiring workers to retrain. There are also risks of misinformation, surveillance, and misuse of personal data. Ethical regulation and transparency are, therefore, essential. Governments must develop policies that protect privacy, ensure accountability, and encourage responsible innovation. Public awareness and digital literacy programmes are necessary so that citizens understand both the benefits and limitations of AI systems.

Beyond economics and services, AI is gradually influencing social relationships and cultural patterns. South Asian societies have traditionally relied on hierarchy and personal authority, but data-driven decision making changes this structure. Agricultural planning may depend on predictive models rather than ancestral practice, and educational evaluation may rely on learning analytics instead of examination rankings alone. This does not eliminate human judgment, but it alters its basis. Societies increasingly value analytical thinking, creativity, and adaptability. Educational systems must, therefore, move beyond memorisation toward critical thinking and interdisciplinary learning.

AI contribution to national development

In Sri Lanka, these changes may contribute to national development if implemented carefully. AI-supported financial monitoring can improve transparency and reduce corruption. Smart infrastructure systems can help manage transportation and urban planning. Communication technologies can support interaction among Sinhala, Tamil, and English speakers, promoting social inclusion in a multilingual society. Assistive technologies can improve accessibility for persons with disabilities, enabling broader participation in education and employment. These developments show that artificial intelligence is not merely a technological innovation but a social instrument capable of strengthening equality when guided by ethical policy.

Symbolic shift

Ultimately, the India AI Impact Summit 2026 represents a symbolic shift in the global technological landscape. It indicates that developing nations are beginning to shape the future of artificial intelligence according to their own social needs rather than passively importing technology. For South Asia and Sri Lanka, the challenge is not whether AI will arrive but how it will be used. If education systems prepare citizens, if governments establish responsible regulations, and if access remains inclusive, AI can become a partner in development rather than a source of inequality. The future will likely involve close collaboration between humans and intelligent systems, where machines assist decision making while human values guide outcomes. In this sense, artificial intelligence does not replace human society, but transforms it, offering Sri Lanka an opportunity to build a more knowledge based, efficient, and equitable social order in the decades ahead.

by Milinda Mayadunna

Features

Governance cannot be a postscript to economics

The visit by IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva to Sri Lanka was widely described as a success for the government. She was fulsome in her praise of the country and its developmental potential. The grounds for this success and collaborative spirit go back to the inception of the agreement signed in March 2023 in the aftermath of Sri Lanka’s declaration of international bankruptcy. The IMF came in to fulfil its role as lender of last resort. The government of the day bit the bullet. It imposed unpopular policies on the people, most notably significant tax increases. At a moment when the country had run out of foreign exchange, defaulted on its debt, and faced shortages of fuel, medicine and food, the IMF programme restored a measure of confidence both within the country and internationally.

Since 1965 Sri Lanka has entered into agreements with the IMF on 16 occasions none of which were taken to their full term. The present agreement is the 17th agreement . IMF agreements have traditionally been focused on economic restructuring. Invariably the terms of agreement have been harsh on the people, with priority being given to ensure the debtor country pays its loans back to the IMF. Fiscal consolidation, tax increases, subsidy reductions and structural reforms have been the recurring features. The social and political costs have often been high. Governments have lost popularity and sometimes fallen before programmes were completed. The IMF has learned from experience across the world that macroeconomic reform without social protection can generate backlash, instability and policy reversals.

The experience of countries such as Greece, Ireland and Portugal in dealing with the IMF during the eurozone crisis demonstrated the political and social costs of austerity, even though those economies later stabilised and returned to growth. The evolution of IMF policies has ensured that there are two special features in the present agreement. The first is that the IMF has included a safety net of social welfare spending to mitigate the impact of the austerity measures on the poorest sections of the population. No country can hope to grow at 7 or 8 percent per annum when a third of its people are struggling to survive. Poverty alleviation measures in the Aswesuma programme, developed with the agreement of the IMF, are key to mitigating the worst impacts of the rising cost of living and limited opportunities for employment.

Governance Included

The second important feature of the IMF agreement is the inclusion of governance criteria to be implemented alongside the economic reforms. It goes to the heart of why Sri Lanka has had to return to the IMF repeatedly. Economic mismanagement did not take place in a vacuum. It was enabled by weak institutions, politicised decision making, non-transparent procurement, and the erosion of checks and balances. In its economic reform process, the IMF has included an assessment of governance related issues to accompany the economic restructuring process. At the top of this list is tackling the problem of corruption by means of publicising contracts, ensuring open solicitation of tenders, and strengthening financial accountability mechanisms.

The IMF also encouraged a civil society diagnostic study and engaged with civil society organisations regularly. The civil society analysis of governance issues which was promoted by Verite Research and facilitated by Transparency International was wider in scope than those identified in the IMF’s own diagnostic. It pointed to systemic weaknesses that go beyond narrow fiscal concerns. The civil society diagnostic study included issues of social justice such as the inequitable impact of targeting EPF and ETF funds of workers for restructuring and the need to repeal abuse prone laws such as the Prevention of Terrorism Act and the Online Safety Act. When workers see their retirement savings restructured without adequate consultation, confidence in policy making erodes. When laws are perceived to be instruments of arbitrary power, social cohesion weakens.

During a meeting between the IMF Managing Director Georgeiva and civil society members last week, there was discussion on the implementation of those governance measures in which she spoke in a manner that was not alien to the civil society representatives. Significantly, the civil society diagnostic report also referred to the ethnic conflict and the breakdown of interethnic relations that led to three decades of deadly war, causing severe economic losses to the country. This was also discussed at the meeting. Governance is not only about accounting standards and procurement rules. It is about social justice, equality before the law, and political representation. On this issue the government has more to do. Ethnic and religious minorities find themselves inadequately represented in high level government committees. The provincial council system that ensured ethnic and minority representation at the provincial level continues to be in abeyance.

Beyond IMF

The significance of addressing governance issues is not only relevant to the IMF agreement. It is also important in accessing tariff concessions from the European Union. The GSP Plus tariff concession given by the EU enables Sri Lankan exports to be sold at lower prices and win markets in Europe. For an export dependent economy, this is critical. Loss of such concessions would directly affect employment in key sectors such as apparel. The government needs to address longstanding EU concerns about the protection of human rights and labour rights in the country. The EU has, for several years, linked the continuation of GSP Plus to compliance with international conventions. This includes the condition that the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) be brought into line with international standards. The government’s alternative in the form of the draft Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PTSA) is less abusive on paper but is wider in scope and retains the core features of the PTA.

Governance and social justice factors cannot be ignored or downplayed in the pursuit of economic development. If Sri Lanka is to break out of its cycle of crisis and bailout, it must internalise the fact that good governance which promotes social justice and more fairly distributes the costs and fruits of development is the foundation on which durable economic growth is built. Without it, stabilisation will remain fragile, poverty will remain high, and the promise of 7 to 8 percent growth will remain elusive. The implementation of governance reforms will also have a positive effect through the creative mechanism of governance linked bonds, an innovation of the present IMF agreement.

The Sri Lankan think tank Verité Research played an important role in the development of governance linked bonds. They reduce the rate of interest payable by the government on outstanding debt on the basis that better governance leads to a reduction in risk for those who have lent their money to Sri Lanka. This is a direct financial reward for governance reform. The present IMF programme offers an opportunity not only to stabilise the economy but to strengthen the institutions that underpin it. That opportunity needs to be taken. Without it, the country cannot attract investment, expand exports and move towards shared prosperity and to a 7-8 percent growth rate that can lift the country out of its debt trap.

by Jehan Perera

Features

MISTER Band … in the spotlight

It’s a good sign, indeed, for the local scene, to see artistes, who have not been very much in the limelight, now making their presence felt, in a big way, and I’m glad to give them the publicity they deserve.

It’s a good sign, indeed, for the local scene, to see artistes, who have not been very much in the limelight, now making their presence felt, in a big way, and I’m glad to give them the publicity they deserve.

On 10th February we had Yellow Beatz in the spotlight and this week it’s MISTER Band.

This outfit is certainly not new to our scene; they have been around since 2012, under the leadership of Sithum Waidyarathne.

The seven energetic members who make up MISTER Band are:

Sithum Waidyarathne (leader/founder/saxophonist/guitarist and vocalist), Rangana Seram (bass guitarist), Vihanga Liyanage (vocalist), Ridmi Dissanayake (female vocalist), Nuwan Cristo (keyboardist/vocalist), Kasun Thennakoon (lead guitarist), and Nuwan Madushanka (drummer).

According to Sithum, their vision is to provide high quality entertainmen to those who engage their services.

“Thanks to our engaging performances and growing popularity, MISTER Band continues to be in high demand … at weddings, corporate events and dinner dances,” said Sithum.

They predominantly cover English and Sinhala music, as well as the most popular genres.

And the reviews that come their way, after a performance, are excellent, they say, and this is one of the bouquets they received:

It was a pleasure to have you at our wedding. Being avid music fans we wanted the best music, not just a big named band, and you guys acceded that expectations. Big thanks to Sithum for being very supportive, attentive and generous.

- Sithum Waidyarathne: Band leader and founder

- Ridmi Dissanayake: MISTER Band’s female vocalist

The best thing is the post feedback from all the guests. Normally we get mixed reviews but the whole crowd was impressed by you.

MISTER Band was one of our best choices for our wedding.

What is interesting is that for the past four consecutive years, this outfit has performed overseas, during New Year’s Eve, thereby taking their music to the international stage, as well.

The band has also produced a collection of original songs, with around six original tracks composed by the band leader, Sithum Waidyarathne, including ‘Suraganak Dutuwa,’ ‘Landuni,’ ‘Dili Dili Payana,’ ‘Hada Wedana,’ and ‘Nil Kandu Athare.’

Two more songs are set to be released this month: ‘Hitha Norida’ and ‘Premaye Hanguman.’

In addition to their original music, they have also created a strong online presence by performing and uploading over 50 cover songs and medleys to YouTube.

“We’re now planning to connect with an even wider audience by releasing more cover content very soon,” said Sithum, adding that they are also very active on social media, under the name Mister Band Official – on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok.

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoVictor Melder turns 90: Railwayman and bibliophile extraordinary

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoReconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

-

Features1 day ago

Features1 day agoLOVEABLE BUT LETHAL: When four-legged stars remind us of a silent killer

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoVictor, the Friend of the Foreign Press

-

Latest News3 days ago

Latest News3 days agoNew Zealand meet familiar opponents Pakistan at spin-friendly Premadasa

-

Latest News3 days ago

Latest News3 days agoTariffs ruling is major blow to Trump’s second-term agenda

-

Latest News3 days ago

Latest News3 days agoECB push back at Pakistan ‘shadow-ban’ reports ahead of Hundred auction