Features

The JVP’s Military Battle for Power

THE APRIL 1971 REVOLT – II

By Jayantha Somasundaram

The JVP evolved in the late 1960s under Rohana Wijeweera as a radical rural youth group. It believed that a socialist change in Sri Lanka could only be effected through a sudden armed insurrection launched simultaneously across the country. Recruits to the JVP underwent a series of political classes as well as military training, while the organisation clandestinely armed itself. The United Front Government responded in March 1971 with a State of Emergency, the arrest of JVP cadre and the deploying of the Army to the provinces.

In March 1971 events rapidly escalated. The JVP believed that the government was planning to use the Army to launch an all out offensive against them. And on 2nd April nine JVP leaders, six members of the Political Bureau and three District Secretaries, met at the Vidyodaya Sangaramaya at a meeting presided over by S.V.A Piyatilake. They took the decision to launch their attack at 2330 hours on 5th April. “The decision taken was to attack on a specific date at a specific time. This decision is completely in line with the evidence that the Fifth Class of the JVP…advocated that in the circumstances of our country, the best method would be to launch simultaneous attacks everywhere,” concluded the Judgement of the Criminal Justice Commission Inquiry No 1 1976.

The date of attack was relayed by pre-arranged code in the contents of a paid radio obituary notice by an unsuspecting state-owned Ceylon Broadcasting Corporation. The JVP cadres at Wellawaya however misinterpreted the instruction and launched their attack on the Wellawaya Police Station 24 hours earlier on the night of 4th April.

The initial targets were rural police stations both in order to further arm themselves and because the JVP viewed the police as the only representative of the state in the countryside. Moreover, they believed that the police and the armed forces were low on ammunition and they discounted the government’s ability to counter attack once the JVP had gained control of the countryside. Besides, the attacks on remote police stations across much of the country’s rural south, a large group also travelled north in order to rescue Wijeweera who was held in Jaffna.

Attacking with home-made weapons in groups of 25 to 30 in order to seize better arms from the police stations, the JVP believed that controlling these rural police stations would provide them with areas of military and political control, thereby denying the government access to such areas which would provide secure rear-bases for subsequent attacks by the JVP on towns and cities. Ten out of the island’s 22 Administrative Districts were battlegrounds. “Ninety two Police Stations had been attacked, damaging fifty and causing around fifty to be abandoned,” wrote Major General Anton Muttukumaru in The Military History of Ceylon.

Piyatilake was responsible for operations in Colombo. He detailed Raja Nimal an Advanced Level student to storm the Rosmead Place residence of Prime Minister Sirima Bandaranaike on the night of the 5th along with 50 student cadre, to capture the Prime Minister and transport her to a place where she would be held. However the expected vehicle and Piyatilake failed to arrive at the prearranged rendezvous in Borella and the attack did not materialise. Meanwhile unaware of the impending danger, the Prime Minister’s security advisers prevailed upon her to move to her official residence at Temple Trees, where she would be more secure.

Elsewhere in the Colombo District a major attack occurred at Hanwella, where the A4 High Level and Low Level Roads converge. Early on the morning of the 6th about 100 JVP combatants using hand bombs, Molotov Cocktails and firearms attacked the Police Station compelling its personnel to abandon their positions and flee into the surrounding jungle. The JVP captured the station’s armoury of weapons, hoisted a red flag and froze transport into Colombo. They held the town until armed police from Homagama supported by troops from Panagoda overpowered them.

The Battle for Kegalle

Athula Nimalasiri Jayasinghe, known within the Movement as Loku Athula, was in charge of the Kegalle and Kurunegala Districts. Once the decision to attack was made he moved into the area on the 3rd, meeting Area Leaders at Weliveriya and coordinating operations with detachments in Veyangoda and Mirigama. About 600 JVP combatants were deployed across the Kegalle District concentrated at Warakapola and Rambukkana.

Under Patrick Fernando, the Pindeniya detachment attacked both the local Police Station and the Bogala Graphite Mines, capturing a lorry load of explosives from the mines. On the 8th the Warakapola Police Station was successfully attacked, its weapons including two sub machine guns seized and the building set ablaze. In addition, Police Stations at Bulathkohupitiya, Aranayaka, Mawanella, Rambukkana and Dedigama were also attacked and the station at Aranayake burned down. Only Kegalle Police Station and the area surrounding it remained under Government control.

The Army could only access the interior regions of the District on the 10th and initially had to focus on removing road blocks and repairing culverts and bridges to gain mobility. When they penetrated the countryside they were frequently ambushed as in Aranayake and both sides sustained casualties. In The JVP 1969-1989 Justice A.C. Alles concludes that “the insurgents had met with considerable success in the Kegalle District.”

On the 12th at Utuwankande the Army was ambushed by the JVP using rifles and submachine guns. But the battle was turning in favour of the Army which brought to bear superior arms to put pressure on the rebels and gradually reopen the abandoned police stations in the district.

Finally on the 29th led by Loku Athula the JVP forces began their withdrawal from the District, from Balapattawa via Alawwa and then north. As they retreated in the direction of the Wilpattu Park they came under attack from the Army and from the air by Air Force helicopters. The Army finally ambushed them near Galgamuwa, killing some and capturing Loku Athula on 7th June.

The experience of the Kegalle District was replicated by the JVP in the Galle, Matara and Hambantota Districts. With the exception of Dickwella all Police Stations in the Matara District were abandoned. While in the Ambalangoda Police Area all stations, Elpitiya, Uragaha, Pitigala and Meetiyagoda fell to the JVP.

Widespread JVP attacks were also launched across the North Central Province where only the Anuradhapura Police Station was spared. As in the Kegalle District the outlying stations had to be abandoned and personnel withdrawn to Anuradhapura. However the Kekirawa Station, though attacked several times, held out. The Army was only able to move into the outlying areas of the Anuradhapura District on the 30th. Further north the Vavuniya Police Station in the Northern Province was also attacked. Less intense activity was reported in the Kandy, Badulla and Moneragala Districts.

N.Sanmugathasan in A Marxist Looks at the History of Ceylon remarked that “The rank and file (of the JVP) seems to have been honestly revolutionary, with a sense of dedication that must be admired, and a willingness to sacrifice their lives – unheard of before in Ceylon.” The first Ceylonese Army Commander General Muttukumaru wrote “Their (JVP) courage was also evident in the display of their military skills which enabled them to control many regions in the country and give battle to the armed forces in fierce guerrilla fighting.”

The military background

In November 1947 on the eve of independence, Ceylon signed a Defence Agreement with the United Kingdom. The military’s threat perception was determined by “the Government’s concern, (which) was invasion by India. The military’s focus was to have a defence force capable of meeting any external threat until assistance arrived from Britain.” In the words of Air Vice-Marshal P.H. ‘Paddy’ Mendis, who was Air Force Commander in 1971, the objective that determined the capabilities of the armed forces therefore was to “hold up an invading force of the enemy until assistance arrived from a bigger country with which we have an alliance.” (Brian Blodgett in Sri Lanka’s Military: The Search for a Mission 1949-2004)

The only military threat perceived was external; there was no anticipation of an internal military threat. Furthermore, in the wake of the 1962 abortive coup against the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) Government, and the alleged 1966 coup against the United National Party Government, both parties that had been in power were wary of the Army which in 1970 had an authorised strength of 329 officers and 6,291 other ranks, and an annual budget of Rs 52 million (US$10mn), just 1.2% of total government expenditure.

Despite these inherent structural limitations, the Government and the Army responded swiftly, appointing regional Co-ordinating Officers in the worst affected districts. They were Colonels E.T. de Z. Abeysekera in Anuradhapura, S. D. Ratwatte in Badulla, Douglas Ramanayake in Galle and Derek Nugawella in Hambantota, Lieutenant Colonels R.R Rodrigo in Jaffna, Cyril Ranatunga in Kegalle, D.J.de S Wickremasinghe in Matara, Tissa Weeratunga in Moneragala and Dennis Hapugalle in Vavuniya.

The Ceylon Volunteer Force was immediately mobilised, and the first military casualty was Staff Sergeant Jothipala of the 2nd Volunteer Battalion, Sinha Regiment [2(V)SR], who was killed at Thulhiriya in the Kurunegala District on the first day of the insurrection. While Sandhurst-trained Major Noel Weerakoon of the 4th Regiment, Ceylon Artillery was the first officer to be killed whilst leading an ammunition convoy from Vavuniya to the besieged town of Anuradhapura; he was wounded when his convoy was ambushed and later succumbed to his injuries.

The battle rages

In 1971 the Royal Ceylon Air Force (RCyAF) consisted of three squadrons: No. 1 Flying Training Squadron with nine Chipmunk trainers based at China Bay, No. 2 Transport Sq. equipped with five Doves, 4 Herons and three Pioneer fixed wing aircraft and four helicopters and No. 3 Reconnaissance Sq. with Cessna aircraft. In the 1960s Britain had gifted five Hunting Jet Provost T51s jet trainers which had gone out of service by 1971.

Beginning at 0900 hours on 5th April the Jet Provost, which were in storage at China Bay, began operating out of this airbase. Armed with Browning machine guns and rockets, they carried out air to ground attacks using 60 lb rockets. The three Bell 206A Jet Ranger helicopters protected by Bren Guns airlifted 36,500 lb of ammunition during April to critical police stations. In addition the Doves carried out supply missions and during the course of April, 900 soldiers and 100,000 lb of equipment were transported by the RCyAF.

The JVP seized parts of the Colombo-Kandy A1 Trunk Route at Warakapola and Kegalle, cutting off the main artery between Colombo and the tea growing highlands. In response the Jet Provost had to mount aerial attacks on the key bridge at Alawwa which led to the downing of a Jet Provost and the death of her pilot.

If not for the premature attack in Wellawaya which resulted in the Police and Military around the country being placed on high alert “the situation would have been very grave for not only would several Police Stations have been captured, but the JVP would have been able to arm itself with modern weapons,” wrote Justice Alles.

Desperate for arms and ammunition in the first days of the rebellion, the Government aware that a Chinese cargo vessel bound for Tanzania with an arms shipment was currently in Colombo Harbour, unsuccessfully appealed to both Beijing and Dar-es-Salaam to make these arms available to Sri Lanka.

International support

As rural police stations fell, the government abandoned others, regrouping its limited forces and anxious to protect the towns and cities. This tactic paid off. The JVP only had equipment captured from police stations. They did not go on to overrun military camps nor capture their more sophisticated weapons. While the JVP did control parts of Kegalle, Elpitiya, Deniyaya and Kataragama uncontested, the Army replenished its meagre stocks of weapons.

Wijeweera had focussed solely on a single decisive blow against the Government. There was no provision to conduct even a short term guerrilla operation, or an attempt to lead a peasant uprising. And during the first 72 hours his strategy appeared to be working. What dramatically altered the balance of forces against the JVP was the immediate and sustained influx of military equipment that flowed in from overseas to enable the armed forces to turn the tide in their favour.

Within four days of the JVP attack, Air Ceylon’s Trident took off from Singapore carrying a consignment of small arms provided by Britain from its base there. The following day the UK agreed to supply six Bell-47G Jet Ranger helicopters armed with 7.62mm machine guns. On 12th April on board a US Air Force Lockheed C-141 Starlifter, Washington shipped out critical spare parts for the RCyAF helicopters which were flying twelve hour days. And at Colombo’s request New Delhi on the 14th sent six Indian Air Force Aérospatiale SA 315B Lama utility helicopters with crews to Katunayake Air Force Base, along with troops to guard them as well as arms, ammunition and grenades. They would remain in-country for three months.

On the 17th Air Ceylon flew in nine tons of military equipment which the Soviet Union made available from supplies in Cairo. While on the 22nd a Soviet Air Force Antonov AN-22 transporter arrived with two Kamov Ka-26 rescue helicopters and five Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 jet fighters and one MiG-17 high-subsonic fighter. The Soviet aircraft were accompanied by 200 trainers and ground crew.

China, Australia, Pakistan and Yugoslavia would also send arms and equipment. Colombo’s Non Aligned foreign policy which enabled it to source and receive military weapons and equipment from countries across the globe had succeeded. However the disparate array of equipment would pose a logistics dilemma for the military.

The sudden influx of arms and ammunition rapidly altered the balance of power against the JVP. For example the Army took Yugoslav artillery into Kegalle to flush out the rebels. And around 16,500 JVP members were captured, arrested or surrendered. The remaining combatants withdrew into jungle sanctuaries in the Kegalle, Elpitiya, Deniyaya and Kataragama areas.

Meanwhile there were reports that the JVP were endeavouring to bring weapons in by sea. But the Royal Ceylon Navy’s frigate and Thorneycroft boats could not secure the island’s territory nor prevent supplies reaching the rebels. This compelled Colombo to rely on the Indian Navy which sent three of its Hunt-class escort destroyers, INS Ganga, INS Gomathi and INS Godawari to patrol Ceylon’s maritime perimeter. In Sri Lanka Navy: Enhanced Role and New Challenges Professor Gamini Keerawella and Lieutenant Commander S. Hemachandre explain that “Sri Lanka’s dependency on the Indian Navy during the Insurgency to patrol its sea frontier in order to prevent arms supply to the Insurgents, was total.”

At Anuradhapura the JVP had established a base camp as well as six sub camps in the surrounding jungle where weapons, explosives and food had been stored. JVP operations in the Rajangana and Tambuttegama areas were controlled from this base camp. A platoon of 1CLI armed with 82mm mortars was sent to Anuradhapura in May and participated in Operation Otthappuwa, under 1CLI 2iC Major Jayawardena to take control of this area. By the end of May the insurrection was completely crushed.

Some counter insurgency operations however continued into the following year. A-Company 1CLI established a forward base in Horowapatana as late as November 1972 from where they carried out combing out operations until April 1973 while 1CLI’s D-Company closed its Kegalle operations only in December 1974.

Outcomes

The international media reported that summary executions had taken place. Writing from Colombo in the Nouvel Observateur on 23rd May, Rene Dumont said “from the Victoria Bridge on 13th April I saw corpses floating down the (Kelani) River which flows through the north of the capital watched by hundreds of motionless people. The Police who had killed them let them float downstream to terrorise the population.” The New York Times in its 15th April edition said that “many were found to have been shot in the back.”

Lieutenant Colonel Cyril Ranatunga commanding troops in Kegalle was emphatic. “We have learned too many lessons from Vietnam and Malaysia. We must destroy them completely.” While another officer was quoted alongside him in the International Herald Tribune of 20th April as saying “Once we are convinced prisoners are insurgents we take them to a cemetery and dispose of them.” And the Washington Post on 9th May quoted a major who said that “we have never had the opportunity to fight a real war in this country. All these years we have been firing at dummies, now we are being put to use.”

One of these public executions became a celebrated case, the brutal murder of Premawathi Manamperi of Kataragama. She had been crowned festival queen at the previous year’s Sinhala New Year celebration. Two soldiers, Lieutenant Wijeysooria and Sergeant Ratnayaka would be convicted, but both claimed their orders were: “Take no prisoners; bump them off, liquidate them.” (Jayasumana Obeysekara Revolutionary Movements in Ceylon in Imperialism and Revolution in South Asia edited by Kathleen Gough and Hari P. Sharma)

Janice Jiggins notes in Caste and Family in the Politics of the Sinhalese 1947-1976 that “Many in the armed services took the view that the fighting was an expression of anti-Govigama resentment and in certain areas went into low caste villages and arrested all the youth, regardless of participation.”

In the aftermath of the insurgency the armed forces expanded. The Air Force which had 1,400 personnel in 1971 grew to 3,100 by 1976. New units were raised: a Special Police Reserve Force, a Volunteer RCyAF and a new Field Security Detachment targeting subversion. The latter was placed under Lieutenant Colonel Anurudha Ratwatte 2(V) SR, the Security Liaison Officer to the Prime Minister. While a new Volunteer Army unit the National Service Regiment, targeting recruits over 35 years provided according to Fred Halliday “a damning sign that the whole of the country’s youth was in opposition to (the Government).”

The JVP uprising broke the back of the left parties which were trapped politically by the insurrection which they could only denounce at the cost of their long term influence. The SLFP too was isolated from its electorate due to the harsh measures adopted; curfew, censorship, trial without jury, postponement of elections, suspension of habeas corpus and other civil rights. Their Government suffered a devastating defeat at the next elections in 1977.

The uprising questioned the efficacy of a parliamentary system that could not accommodate a generation of educated youth, nor keep politicians aware of their needs and strengths. The decades-old mass national parties seemed to have no place for them. And the JVP charge that the leaders in parliament were of a different class and therefore they themselves of a different sub culture, seemed valid.

Features

Ranking public services with AI — A roadmap to reviving institutions like SriLankan Airlines

Efficacy measures an organisation’s capacity to achieve its mission and intended outcomes under planned or optimal conditions. It differs from efficiency, which focuses on achieving objectives with minimal resources, and effectiveness, which evaluates results in real-world conditions. Today, modern AI tools, using publicly available data, enable objective assessment of the efficacy of Sri Lanka’s government institutions.

Among key public bodies, the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka emerges as the most efficacious, outperforming the Department of Inland Revenue, Sri Lanka Customs, the Election Commission, and Parliament. In the financial and regulatory sector, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) ranks highest, ahead of the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Public Utilities Commission, the Telecommunications Regulatory Commission, the Insurance Regulatory Commission, and the Sri Lanka Standards Institution.

Among state-owned enterprises, the Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA) leads in efficacy, followed by Bank of Ceylon and People’s Bank. Other institutions assessed included the State Pharmaceuticals Corporation, the National Water Supply and Drainage Board, the Ceylon Electricity Board, the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation, and the Sri Lanka Transport Board. At the lower end of the spectrum were Lanka Sathosa and Sri Lankan Airlines, highlighting a critical challenge for the national economy.

Sri Lankan Airlines, consistently ranked at the bottom, has long been a financial drain. Despite successive governments’ reform attempts, sustainable solutions remain elusive.

Globally, the most profitable airlines operate as highly integrated, technology-enabled ecosystems rather than as fragmented departments. Operations, finance, fleet management, route planning, engineering, marketing, and customer service are closely coordinated, sharing real-time data to maximise efficiency, safety, and profitability.

The challenge for Sri Lankan Airlines is structural. Its operations are fragmented, overly hierarchical, and poorly aligned. Simply replacing the CEO or senior leadership will not address these deep-seated weaknesses. What the airline needs is a cohesive, integrated organisational ecosystem that leverages technology for cross-functional planning and real-time decision-making.

The government must urgently consider restructuring Sri Lankan Airlines to encourage:

=Joint planning across operational divisions

=Data-driven, evidence-based decision-making

=Continuous cross-functional consultation

=Collaborative strategic decisions on route rationalisation, fleet renewal, partnerships, and cost management, rather than exclusive top-down mandates

Sustainable reform requires systemic change. Without modernised organisational structures, stronger accountability, and aligned incentives across divisions, financial recovery will remain out of reach. An integrated, performance-oriented model offers the most realistic path to operational efficiency and long-term viability.

Reforming loss-making institutions like Sri Lankan Airlines is not merely a matter of leadership change — it is a structural overhaul essential to ensuring these entities contribute productively to the national economy rather than remain perpetual burdens.

By Chula Goonasekera – Citizen Analyst

Features

Why Pi Day?

International Day of Mathematics falls tomorrow

The approximate value of Pi (π) is 3.14 in mathematics. Therefore, the day 14 March is celebrated as the Pi Day. In 2019, UNESCO proclaimed 14 March as the International Day of Mathematics.

Ancient Babylonians and Egyptians figured out that the circumference of a circle is slightly more than three times its diameter. But they could not come up with an exact value for this ratio although they knew that it is a constant. This constant was later named as π which is a letter in the Greek alphabet.

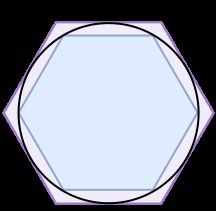

It was the Greek mathematician Archimedes (250 BC) who was able to find an upper bound and a lower bound for this constant. He drew a circle of diameter one unit and drew hexagons inside and outside the circle such that the sides of each hexagon touch the sides of the circle. In mathematics the circle passing through all vertices of a polygon is called a ‘circumcircle’ and the largest circle that fits inside a polygon tangent to all its sides is called an ‘incircle’. The total length of the smaller hexagon then becomes the lower bound of π and the length of the hexagon outside the circle is the upper bound. He realised that by increasing the number of sides of the polygon can make the bounds get closer to the value of Pi and increased the number of sides to 12,24,48 and 60. He argued that by increasing the number of sides will ultimately result in obtaining the original circle, thereby laying the foundation for the theory of limits. He ended up with the lower bound as 22/7 and the upper bound 223/71. He could not continue his research as his hometown Syracuse was invaded by Romans and was killed by one of the soldiers. His last words were ‘do not disturb my circles’, perhaps a reference to his continuing efforts to find the value of π to a greater accuracy.

Archimedes can be considered as the father of geometry. His contributions revolutionised geometry and his methods anticipated integral calculus. He invented the pulley and the hydraulic screw for drawing water from a well. He also discovered the law of hydrostatics. He formulated the law of levers which states that a smaller weight placed farther from a pivot can balance a much heavier weight closer to it. He famously said “Give me a lever long enough and a place to stand and I will move the earth”.

Mathematicians have found many expressions for π as a sum of infinite series that converge to its value. One such famous series is the Leibniz Series found in 1674 by the German mathematician Gottfried Leibniz, which is given below.

π = 4 ( 1 – 1/3 + 1/5 – 1/7 + 1/9 – ………….)

The Indian mathematical genius Ramanujan came up with a magnificent formula in 1910. The short form of the formula is as follows.

π = 9801/(1103 √8)

For practical applications an approximation is sufficient. Even NASA uses only the approximation 3.141592653589793 for its interplanetary navigation calculations.

It is not just an interesting and curious number. It is used for calculations in navigation, encryption, space exploration, video game development and even in medicine. As π is fundamental to spherical geometry, it is at the heart of positioning systems in GPS navigations. It also contributes significantly to cybersecurity. As it is an irrational number it is an excellent foundation for generating randomness required in encryption and securing communications. In the medical field, it helps to calculate blood flow rates and pressure differentials. In diagnostic tools such as CT scans and MRI, pi is an important component in mathematical algorithms and signal processing techniques.

This elegant, never-ending number demonstrates how mathematics transforms into practical applications that shape our world. The possibilities of what it can do are infinite as the number itself. It has become a symbol of beauty and complexity in mathematics. “It matters little who first arrives at an idea, rather what is significant is how far that idea can go.” said Sophie Germain.

Mathematics fans are intrigued by this irrational number and attempt to calculate it as far as they can. In March 2022, Emma Haruka Iwao of Japan calculated it to 100 trillion decimal places in Google Cloud. It had taken 157 days. The Guinness World Record for reciting the number from memory is held by Rajveer Meena of India for 70000 decimal places over 10 hours.

Happy Pi Day!

The author is a senior examiner of the International Baccalaureate in the UK and an educational consultant at the Overseas School of Colombo.

by R N A de Silva

Features

Sheer rise of Realpolitik making the world see the brink

The recent humanly costly torpedoing of an Iranian naval vessel in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone by a US submarine has raised a number of issues of great importance to international political discourse and law that call for elucidation. It is best that enlightened commentary is brought to bear in such discussions because at present misleading and uninformed speculation on questions arising from the incident are being aired by particularly jingoistic politicians of Sri Lanka’s South which could prove deleterious.

The recent humanly costly torpedoing of an Iranian naval vessel in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone by a US submarine has raised a number of issues of great importance to international political discourse and law that call for elucidation. It is best that enlightened commentary is brought to bear in such discussions because at present misleading and uninformed speculation on questions arising from the incident are being aired by particularly jingoistic politicians of Sri Lanka’s South which could prove deleterious.

As matters stand, there seems to be no credible evidence that the Indian state was aware of the impending torpedoing of the Iranian vessel but these acerbic-tongued politicians of Sri Lanka’s South would have the local public believe that the tragedy was triggered with India’s connivance. Likewise, India is accused of ‘embroiling’ Sri Lanka in the incident on account of seemingly having prior knowledge of it and not warning Sri Lanka about the impending disaster.

It is plain that a process is once again afoot to raise anti-India hysteria in Sri Lanka. An obligation is cast on the Sri Lankan government to ensure that incendiary speculation of the above kind is defeated and India-Sri Lanka relations are prevented from being in any way harmed. Proactive measures are needed by the Sri Lankan government and well meaning quarters to ensure that public discourse in such matters have a factual and rational basis. ‘Knowledge gaps’ could prove hazardous.

Meanwhile, there could be no doubt that Sri Lanka’s sovereignty was violated by the US because the sinking of the Iranian vessel took place in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone. While there is no international decrying of the incident, and this is to be regretted, Sri Lanka’s helplessness and small player status would enable the US to ‘get away with it’.

Could anything be done by the international community to hold the US to account over the act of lawlessness in question? None is the answer at present. This is because in the current ‘Global Disorder’ major powers could commit the gravest international irregularities with impunity. As the threadbare cliché declares, ‘Might is Right’….. or so it seems.

Unfortunately, the UN could only merely verbally denounce any violations of International Law by the world’s foremost powers. It cannot use countervailing force against violators of the law, for example, on account of the divided nature of the UN Security Council, whose permanent members have shown incapability of seeing eye-to-eye on grave matters relating to International Law and order over the decades.

The foregoing considerations could force the conclusion on uncritical sections that Political Realism or Realpolitik has won out in the end. A basic premise of the school of thought known as Political Realism is that power or force wielded by states and international actors determine the shape, direction and substance of international relations. This school stands in marked contrast to political idealists who essentially proclaim that moral norms and values determine the nature of local and international politics.

While, British political scientist Thomas Hobbes, for instance, was a proponent of Political Realism, political idealism has its roots in the teachings of Socrates, Plato and latterly Friedrich Hegel of Germany, to name just few such notables.

On the face of it, therefore, there is no getting way from the conclusion that coercive force is the deciding factor in international politics. If this were not so, US President Donald Trump in collaboration with Israeli Rightist Premier Benjamin Natanyahu could not have wielded the ‘big stick’, so to speak, on Iran, killed its Supreme Head of State, terrorized the Iranian public and gone ‘scot-free’. That is, currently, the US’ impunity seems to be limitless.

Moreover, the evidence is that the Western bloc is reuniting in the face of Iran’s threats to stymie the flow of oil from West Asia to the rest of the world. The recent G7 summit witnessed a coming together of the foremost powers of the global North to ensure that the West does not suffer grave negative consequences from any future blocking of western oil supplies.

Meanwhile, Israel is having a ‘free run’ of the Middle East, so to speak, picking out perceived adversarial powers, such as Lebanon, and militarily neutralizing them; once again with impunity. On the other hand, Iran has been bringing under assault, with no questions asked, Gulf states that are seen as allying with the US and Israel. West Asia is facing a compounded crisis and International Law seems to be helplessly silent.

Wittingly or unwittingly, matters at the heart of International Law and peace are being obfuscated by some pro-Trump administration commentators meanwhile. For example, retired US Navy Captain Brent Sadler has cited Article 51 of the UN Charter, which provides for the right to self or collective self-defence of UN member states in the face of armed attacks, as justifying the US sinking of the Iranian vessel (See page 2 of The Island of March 10, 2026). But the Article makes it clear that such measures could be resorted to by UN members only ‘ if an armed attack occurs’ against them and under no other circumstances. But no such thing happened in the incident in question and the US acted under a sheer threat perception.

Clearly, the US has violated the Article through its action and has once again demonstrated its tendency to arbitrarily use military might. The general drift of Sadler’s thinking is that in the face of pressing national priorities, obligations of a state under International Law could be side-stepped. This is a sure recipe for international anarchy because in such a policy environment states could pursue their national interests, irrespective of their merits, disregarding in the process their obligations towards the international community.

Moreover, Article 51 repeatedly reiterates the authority of the UN Security Council and the obligation of those states that act in self-defence to report to the Council and be guided by it. Sadler, therefore, could be said to have cited the Article very selectively, whereas, right along member states’ commitments to the UNSC are stressed.

However, it is beyond doubt that international anarchy has strengthened its grip over the world. While the US set destabilizing precedents after the crumbling of the Cold War that paved the way for the current anarchic situation, Russia further aggravated these degenerative trends through its invasion of Ukraine. Stepping back from anarchy has thus emerged as the prime challenge for the world community.

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoPeradeniya Uni issues alert over leopards in its premises

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoRepatriation of Iranian naval personnel Sri Lanka’s call: Washington

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoWife raises alarm over Sallay’s detention under PTA

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoWinds of Change:Geopolitics at the crossroads of South and Southeast Asia

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoProf. Dunusinghe warns Lanka at serious risk due to ME war

-

Latest News6 days ago

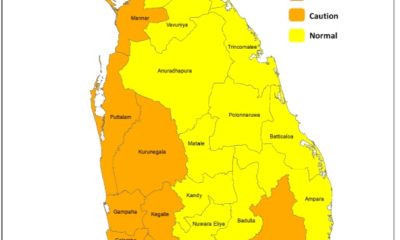

Latest News6 days agoHeat Index at ‘Caution Level’ in the Sabaragamuwa province and, Colombo, Gampaha, Kurunegala, Anuradhapura, Vavuniya, Hambanthota and Monaragala districts

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoRoyal start favourites in historic Battle of the Blues

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoThe final voyage of the Iranian warship sunk by the US