Features

The Foreign Policy of the United States

(A talk given at The Bandaranaike International Training Institute on 09 September, 2025)

The topic I was invited to speak on today is the foreign policy of the United States. This is a very broad theme and to give you a detailed account of it, in the time at our disposal today, would be impossible. So, what I shall attempt to do is to give you a summary or a thumbnail sketch of the foreign policy of the United States from 1776 to the 1930s focusing in particular on two presidents who took charge of the foreign policy of the US during their terms of office: William McKinley and Woodrow Wilson. And thereafter reflect more closely on the period from 1941 to the present. It is believed that the farewell address of President George Washington outlined the foreign policy goals of the United States which included, among others, the cultivation of peace and harmony with all nations. It recommended the avoidance of permanent alliances with “any portion of the foreign world” and advocated trade with all nations. In the early years of the existence of the United States, the most important goal of its foreign policy was to balance the relations with Great Britain and France. Of the two major political parties at that time, the Federalist Party sought close ties with Britain but the Democratic-Republican Party favoured France.

Broadly stated, the striking feature of the history of US foreign policy since the American Revolution is the shift from isolationism before and after World War 1 to interventionism post-World War 11, especially during the Cold War period which lasted for about four decades and a half from 1947 to 1990/91 during which the United States played a hegemonic role in the world.

Isolationism usually describes a policy of non-interventionism: avoiding foreign alliances and conflicts and waging war only if attacked by an adversary. A characteristic feature noticeable in the history of US foreign policy has been a tension between the desire to withdraw from messy foreign problems and the belief that America should be the dominant force in world affairs- – “the indispensable nation”, as former Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright put it.

Generally, it has been the Republicans who have preached withdrawal, though it was the Democrats who did so during the Vietnam War and its aftermath. US foreign policy over the years, has alternated between isolationism and interventionism. It should be noted that despite the election campaign rhetoric of then candidate Donald Trump, one cannot see the likelihood of an imminent US withdrawal from the world.

America’s Founders saw America’s geographical isolation from Europe as an ideal opportunity to develop the new nation in solitude. “Our detached and distant situation invites and enables us to pursue a different course”, Washington said in his farewell address in 1796 (referred to above). Thomas Jefferson too, warned against “entangling alliances”. With the exception of the successful 1846-1848 Mexican War, which expanded US borders to include California and much of the American west, the US was disinclined to get involved in military adventures in other parts of the world. America does not go “abroad in search of monsters to destroy”, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams had declared in 1821.

A turning point, however, was the Spanish-American War. During Cuba’s revolt against Spain in 1898, President William McKinley sent the battleship Maine on a goodwill visit to Havana where it blew up in the harbour, killing around 250 US sailors. Certain American historians of today, are of the view that an internal explosion destroyed the ship, but at the time, Americans led by the American press took a position of extreme patriotism blaming Spain for the explosion and the US declared war. It ended with the surrender of Spain and the war made Theodore (Teddy) Roosevelt, who led the volunteer Rough Riders regiment, a national hero. When Roosevelt succeeded to the presidency after McKinley’s assassination in 1901, he pursued a robust and aggressive foreign policy. It was Roosevelt’s view that the US must “Speak softly and carry a big stick”. To promote US interests abroad- – commercial interests in particular – Roosevelt ordered the construction of the Panama Canal which connects the Pacific and Atlantic oceans and benefits the United States both economically and national security-wise, and negotiated the end of the war between Russia and Japan. It was Roosevelt, according to the historian Richard Abrams, who asked the Americans to assume the responsibility “to use their power for good internationally”.

In the 1890s, one notices a historic turn in US foreign policy. After emerging victorious in its war with Spain in 1898, the United States gained new territory in the Caribbean and the western Pacific. The then Assistant Secretary of State, John Bassett Moore observed that the nation has moved,

. . . from a position of comparative freedom from entanglements into the position of what is commonly called a world power . . . .

Moore’s boss, President William McKinley, presided over these changes. McKinley won the 1896 elections over the highly popular Democrat, William Jennings Bryan. According to Walter LaFeber (1989), “The affection Americans felt for McKinley ranked with the feelings they later had toward the popular Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Dwight D. Eisenhower”. On becoming president in 1896, McKinley himself took control of formulating US foreign policy. Controlling foreign policy in the manner he did, McKinley became not only the first 20th century president, but the first modern chief executive. He is known to have been adept at controlling the US Congress while he kept control of foreign policy in his own hands. McKinley expanded the Constitution’s Commander-in-Chief powers and was thus able to dispatch US troops to fight in China. Historians note that McKinley’s actions paved the way for the “imperial presidency” of the 1960s and 1970s.

McKinley won the presidency and moved to the White House in 1896, thanks largely to the splendid campaign organized by Marcus Hanna, fellow Ohioan and millionaire steel industrialist. McKinley rewarded Hanna by having him appointed to the Senate seat vacated by John Sherman who was named Secretary of State. In Hanna, McKinley had a trusted power broker in the Senate who was both loyal and obedient to the President. These two men built such a powerful political coalition so much so that only one Democrat presidential nominee would be elected president between 1896 and 1932. In 1900, McKinley defeated the Democratic nominee, Bryan more decisively than four years before. And McKinley is credited with having led the United States into the small select circle of great world powers. Yet, like Abraham Lincoln who did much for the United States before him, McKinley was assassinated in September 1901, a mere six months after his second inauguration.

The next to make a significant contribution to US foreign policy was Woodrow Wilson the 28th president of the United States, who was the sole Democrat to be elected president between 1896 and 1932, as referred to above. He was also the first native Southerner to reach the White House since 1849. He is also the only US president to hold a doctorate which he obtained from Johns Hopkins University in 1886. He served as president of Princeton University from 1902 -1910. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1920 for his contribution to ending World War 1 and for creating the League of Nations. Many later presidents including Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon and Jimmy Carter, looked back to Wilson as the Chief Executive whose vision of the nation’s future was far-seeing, and one who had confronted challenges which have continued to worry the United States.

Wilson’s contribution as president from 1913 to 1921, both in terms of domestic and foreign policy, was impressive. What revived US isolationism during the second term of Woodrow Wilson was America’s horrified response to World War 1. The US entered the “war to end all wars” in 1917 with intense patriotic fervour, influenced perhaps by Wilson’s desire, “to make the world safe for democracy”, a phrase Wilson used in a speech to Congress. But the carnage in Europe- – 17 million dead and another 20 million wounded, according to available statistics, sparked another withdrawal into isolationism.

And the Americans then withdrew into the pursuit of material wealth and fun during the 1920s (described as the ‘Roaring Twenties’) and continued to be a world power, indeed the greatest economic power at that time. By 1933, however, the dollar had collapsed. The delicate treaty structure the US had built, fell on top of it (LaFeber, 1994). In the words of the historian, John M. Carroll, “The foundations of economic and political stability” laid during the 1920s were simply “swept away during the economic crisis of the 1930s” consequent to the Great Depression that began in 1929. Washington’s response now came from the newly elected president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, who entered the White House in 1933. The banking system had collapsed, unemployment was rife and there was political chaos internationally with Hitler and the Japanese expansionists beginning to shape world politics. And if these challenges were not enough, Roosevelt was confronted at home by an “isolationist Congress”. US isolationism, however, was challenged by the outbreak of World War 11. Roosevelt was strongly supportive of the allies from 1932 to 1938, and the United States began to provide military equipment to them without entering the war. Things changed dramatically in 1941 when Japan attacked Pearl Harbour in December of that year.

The attack by the Empire of Japan on Pearl Harbour was totally unexpected. It targeted the United States’ Pacific fleet at its naval base in Hawaii on 7 December, 1941. The provocation for this surprise Japanese attack is believed to be due to what Japan perceived to be US interference in Japan’s affairs. Japan declared war on the US and the British on 8 December, and on the same day, both the United Kingdom and the United States declared war on Japan. Although there were no formal obligations for them to do so, both Germany and Italy declared war on the United States, at which point the United Kingdom and the United States retaliated by declaring war on Germany and Italy.

The year 2025 may be looked back upon by future historians, as the end of the Atlanticist era, according to Robert Lyman, the British military historian in his article, The end of the Atlanticist era. This era, begun in 1941, was one in which the United States took on from the United Kingdom, the “White Man’s burden” of keeping the world safe for democracy. Unlike the previous era, which began after World War 1 in 1918, when the United States was steadfastly isolationist, post 1941, the US embarked on being the global guarantor of the Atlantic Charter. This was a signed agreement which committed the two countries to a new set of global security imperatives that would eventually make the United States a super power once Hitler and German fascism had been defeated. But we need to bear in mind that what really motivated the United States to come out of its self-imposed isolationism was the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour.

Pearl Harbour not only led the United States to formally enter World War 11, but it encouraged President Roosevelt to expedite the construction of the atomic bomb which was code-named the Manhattan Project. The Bomb altered the subsequent history of the United States as Gary Wills notes in his Bomb Power The Modern Presidency and The National Security State (2010). Wills also observes that the Manhattan Project which was carried out in secret and was secretly funded at the behest of President Roosevelt, was “a model for the covert activities and covert authority” of the government of the United States since 1942. The US Congress was unaware of the Manhattan Project and even Vice President Harry Truman was kept in the dark. It was only when he succeeded Roosevelt as President that he came to know of it. The executive power in the United States since World War 11 has basically been “Bomb Power”, according to Gary Wills.

The United States became a leading economic, political and military power at the end of World War 11 in September, 1945. It considered itself to be the leader of the free world. Soon however, there began a period of geopolitical rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies. Begun in 1947, the Cold War, ended in December, 1989, when President Bush and Soviet General Secretary Gorbachev declared so at the Malta Summit. Some others considered the end of the Cold War to be two years later in December, 1991, with the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Let us now look at the United States and its performance on the foreign policy front after 1945. In August of 1945, the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. These bombings reportedly killed between 150,000 and 246,000 civilians with many others suffering long- term effects of radiation. This event marked the beginning of the nuclear age. Some historians claim that Japan was on the verge of surrender at this time and thus the decision of the Truman administration to go ahead with the bombings remains a historical and moral debate to-date.

The Cold War led the United States into a number of overt conflicts and covert operations. Among the former are the Korean War (1950-1953) which was armed conflict between North Korea and South Korea. The former was supported by China and the Soviet Union, while the latter, by the United Nations Command (UNC) led by the United States. This was really one of the first proxy wars during the Cold War because, although the it was ostensibly the UNC which went to the defense of South Korea, it was the United States which provided around 90% of the military personnel. Then came the overthrow of Mohammad Mossadegh, the democratically elected Prime Minister of Iran, after he nationalized the oil industry in 1953. The CIA under the orders of the Eisenhower administration, with the backing of Britain’s MI6, accomplished this task. The goal was to restore the pro-Western Shah’s dictatorial rule and thereby maintain Western control over Iranian oil. This fact was exposed in a film titled, ‘Coup ‘53’ directed by the Iranian Taghi Amirani. For the record, let me note that the British government has never admitted its role in the Mossdegh affaire.

The Vietnam War lasted from 1955-1975. North Vietnam, a communist state, and the southern-based Viet Cong (or the National Liberation Front) fought alongside North Vietnam and their stated goal was to unify Vietnam. And South Vietnam, a non-communist state, was supported by the United States. Australia, South Korea, Thailand and New Zealand joined the United States in support of South Vietnam while the Soviet Union and China backed North Vietnam. In the 1950s, the US provided military and economic aid to South Vietnam. The US viewed the Vietnam War, as with the Korean War earlier, from the perspective of the Cold War and the “domino theory”. Successive presidents of the United States and innumerable pundits created the “domino theory”. As goes Vietnam so goes the whole of Asia, like a cascade of dominoes falling into the communist camp. Public debate was structured around the ‘fear factor’, the epic struggle with the “evil empire” or the global communist conspiracy. No US president actually believed in this scare story. The greatest problem of presidents from Eisenhower to Johnson and beyond was contending with their own national security bureaucracy who, in concert with the public and political mood, planned and sought to operate as if the scare story were fact.

There are allegations that the United States and its allies sponsored and facilitated state terrorism and mass killings on a significant scale during the Cold War. The justification given by some for this was that it was to contain Communism, but others say, it was also a strategy by which to buttress the interests of the business elites of the United States and to promote the expansion of capitalism and liberalisation. This reminds us of the immortal words of President Eisenhower, who in his farewell address of 1961 warned his fellow Americans of the Military- Industrial Complex. The most notorious of the post- Cold War conflicts was the US-led coalition’s attack on Iraq in March 2003, that centred around false claims that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) and that Sadam Hussein was supporting Al- Queda. The UK, Australia and Poland were members that joined the US in forming that coalition. Of the present conflicts, the Ukraine war and the Israel-Palestine war are conflicts in which the US is on the side of Ukraine and Israel.

The American interventions were not confined to Asia alone. Patricia McSherry, a professor of political science at Long Island University, states that, ‘hundreds of thousands of Latin Americans were tortured, abducted or killed by right-wing military regimes as part of the US-led anti-communist crusade’, which included support for ‘Operation Condor’ and the Guatemalan military during the Guatemalan civil war. We could add to this list, the US covert interventions in Nicaragua, Chile, Bolivia, Uruguay and Argentina.

Contemporary research and declassified documents demonstrate that the United States and some of its western allies directly facilitated and encouraged the mass murder of a large number of suspected communists in Indonesia during the mid -1960s. According to the American journalist and author, Glenn Greenwald, the strategic rationale of the US support for brutal and genocidal dictatorships around the globe has been consistent since the end of World War 11. This is in keeping with American threats to impose sanctions on officials at the International Criminal Court (ICC) because it issued arrest warrants for Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his former defense minister Yoav Gallant over suspected war crimes in Gaza. Some defenders of the post- 1945 US foreign policy argue that a policy of rhetoric, while doing things counter to that rhetoric was necessary in the sense of realpolitik. According to these defenders, such a policy helped secure victory against the dangers of tyranny and totalitarianism, even though such justification runs counter to the ideology of the rules-based liberal order that the US and its allies in Western Europe introduced after the end of World War 11.

Godfrey Hodgson, a shrewd and highly-respected British commentator, in a fine if provocative book titled, The Myth of American Exceptionalism (2009), offers a bracing critique of America’s view that it has an obligation to redeem other nations. He argues that the idea that the United States is destined to spread its unique gifts of democracy and capitalism to other countries, is dangerous for Americans and for the rest of the world. Furthermore, he asserts that America is not as exceptional as it would like to think; its blindness to its own history has bred a complacent nationalism and a disastrous foreign policy that has alienated it from the global community.

Ziauddin Sardar and Merryl Wyn Davies posed the following apt questions in their book, Will America Change? (2008): Is what’s good for America, good for the world? Or does the world long for America to participate in collective decision-making based on listening to and learning from others, acknowledging thereby the equal validity of different interests and opinions? They go on to say that America’s problem with the world is inseparable from defining and understanding the world’s problems with America. Unless one knows the problem, there can be no effective solution. And the problem lies in how the United States comes to terms with the realities of an increasingly inter-connected and inter-dependent world.

The world today is very different from what it was in 1945. As a former prime minister and foreign minister of Sweden, Carl Bildt, in a recent essay titled, Farewell America: Trump’s isolationism leaves a widening void in world order (2025) writes,

To be sure, America’s power and influence have already waned. For decades after World War 11, the United States could shape the global system to serve its own purposes; and during the brief ‘unipolar’ moment that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union, its status was unrivaled. But other powers have since grown in stature and are pursuing global ambitions. While China is the most obvious example, Europe too, is seeking the unity required to assert itself as a serious global player, and many middle powers want to raise their profiles as well

.Following up on Carl Bildt’s above observations, I’d like to believe that we are on the verge of a more inclusive new world order, in which the voices and interests of the Asian and African states are accommodated. Common challenges facing the world today like climate change, disease, poverty, nuclear proliferation, wars and inequality between peoples and nations require cooperation and coexistence. China and India are at the forefront of a battle to seek a more balanced international system and the likelihood of them combining their resources to seek that balance seems to be in the offing. In this likely new world order, it is envisaged that the hegemony of any one power will be challenged. In this context, the recent meeting of minds at the Shanghai Corporation Organisation (SC0) Summit held in Tianjin, China, the largest summit in SCO’s history, is an encouraging sign. The enlarged BRICS group, so the economists tell us, are already catching up with the G-7 in terms of purchasing of power parity (PPP). The SCO’s areas of action include internal security, counter-terrorism, economic cooperation and military cooperation. In combination with the association of Southeast Nations (ASEAN), the BRICS group and the SCO should form a formidable bloc. And if the members of the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership (also known as the Barcelona Process), a Union of EU member states and 16 southern Mediterranean countries built for economic integration were to join this bloc, then we are closer to a new international order based on multilateralism where the United States, given its greater military strength may have primacy but not hegemony as it has had in the post-1945 world to date.

References

Understanding Power The Indispensable Chomsky,

edited by Peter R. Mitchell and John Schoeffel (2003).

The American Age US Foreign Policy At Home and Abroad Volume 2-since 1896

, Walter LaFeber (1994).

American Foreign Policy Since World War 11,

John Spanier (1989).

The Myth of American Exceptionalism

, Godfrey Hodgson, (2009).

The Fire This Time U.S. War Crimes in the Gulf

, Ramsey Clark, (1992).

Bomb Power The Modern Presidency And The National Security State

, Gary Wills, (2010).

Will America Change?,

Ziauddin Sardar and Merryl Wyn Davies, (2008).

The Disuniting of America Reflections on a Multicultural Society

, Arthur Schlesinger Jr., (1992).

Perilous Power The Middle East & U.S. Foreign Policy Dialogues on Terror, Democracy, War and Justice,

Noam Chomsky and Gilbert Achcar, (2007).

The Unfinished Nation A Concise History of the American People

, Alan Brinkley, (1997).

The Unfinished Journey America Since World War 11

, William H. Chafe, (1996).

Democracy in America

, Alexis de Tocqueville, (translated by George Lawrence and edited by J.P. Mayer), 1988.

by Tissa Jayatilaka ✍️

Features

Disaster-proofing paradise: Sri Lanka’s new path to global resilience

iyadasa Advisor to the Ministry of Science & Technology and a Board of Directors of Sri Lanka Atomic Energy Regulatory Council A value chain management consultant to www.vivonta.lk

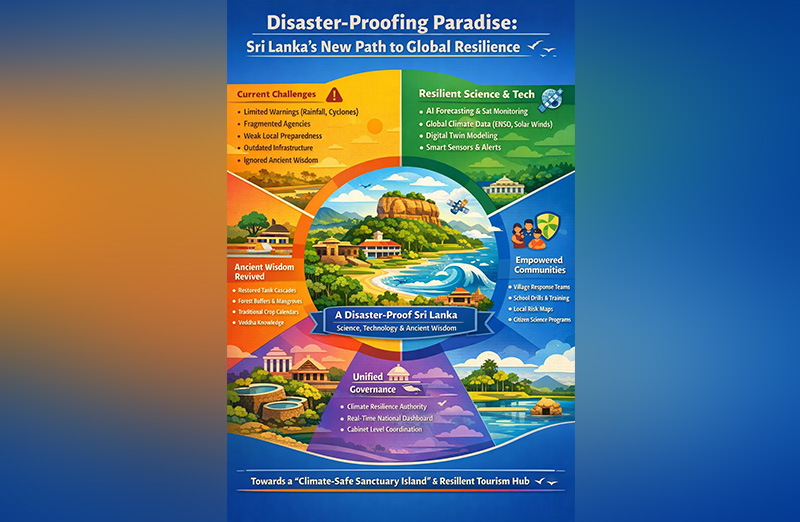

As climate shocks multiply worldwide from unseasonal droughts and flash floods to cyclones that now carry unpredictable fury Sri Lanka, long known for its lush biodiversity and heritage, stands at a crossroads. We can either remain locked in a reactive cycle of warnings and recovery, or boldly transform into the world’s first disaster-proof tropical nation — a secure haven for citizens and a trusted destination for global travelers.

The Presidential declaration to transition within one year from a limited, rainfall-and-cyclone-dependent warning system to a full-spectrum, science-enabled resilience model is not only historic — it’s urgent. This policy shift marks the beginning of a new era: one where nature, technology, ancient wisdom, and community preparedness work in harmony to protect every Sri Lankan village and every visiting tourist.

The Current System’s Fatal Gaps

Today, Sri Lanka’s disaster management system is dangerously underpowered for the accelerating climate era. Our primary reliance is on monsoon rainfall tracking and cyclone alerts — helpful, but inadequate in the face of multi-hazard threats such as flash floods, landslides, droughts, lightning storms, and urban inundation.

Institutions are fragmented; responsibilities crisscross between agencies, often with unclear mandates and slow decision cycles. Community-level preparedness is minimal — nearly half of households lack basic knowledge on what to do when a disaster strikes. Infrastructure in key regions is outdated, with urban drains, tank sluices, and bunds built for rainfall patterns of the 1960s, not today’s intense cloudbursts or sea-level rise.

Critically, Sri Lanka is not yet integrated with global planetary systems — solar winds, El Niño cycles, Indian Ocean Dipole shifts — despite clear evidence that these invisible climate forces shape our rainfall, storm intensity, and drought rhythms. Worse, we have lost touch with our ancestral systems of environmental management — from tank cascades to forest sanctuaries — that sustained this island for over two millennia.

This system, in short, is outdated, siloed, and reactive. And it must change.

A New Vision for Disaster-Proof Sri Lanka

Under the new policy shift, Sri Lanka will adopt a complete resilience architecture that transforms climate disaster prevention into a national development strategy. This system rests on five interlinked pillars:

Science and Predictive Intelligence

We will move beyond surface-level forecasting. A new national climate intelligence platform will integrate:

AI-driven pattern recognition of rainfall and flood events

Global data from solar activity, ocean oscillations (ENSO, MJO, IOD)

High-resolution digital twins of floodplains and cities

Real-time satellite feeds on cyclone trajectory and ocean heat

The adverse impacts of global warming—such as sea-level rise, the proliferation of pests and diseases affecting human health and food production, and the change of functionality of chlorophyll—must be systematically captured, rigorously analysed, and addressed through proactive, advance decision-making.

This fusion of local and global data will allow days to weeks of anticipatory action, rather than hours of late alerts.

Advanced Technology and Early Warning Infrastructure

Cell-broadcast alerts in all three national languages, expanded weather radar, flood-sensing drones, and tsunami-resilient siren networks will be deployed. Community-level sensors in key river basins and tanks will monitor and report in real-time. Infrastructure projects will now embed climate-risk metrics — from cyclone-proof buildings to sea-level-ready roads.

Governance Overhaul

A new centralised authority — Sri Lanka Climate & Earth Systems Resilience Authority — will consolidate environmental, meteorological, Geological, hydrological, and disaster functions. It will report directly to the Cabinet with a real-time national dashboard. District Disaster Units will be upgraded with GN-level digital coordination. Climate literacy will be declared a national priority.

People Power and Community Preparedness

We will train 25,000 village-level disaster wardens and first responders. Schools will run annual drills for floods, cyclones, tsunamis and landslides. Every community will map its local hazard zones and co-create its own resilience plan. A national climate citizenship programme will reward youth and civil organisations contributing to early warning systems, reforestation (riverbank, slopy land and catchment areas) , or tech solutions.

Reviving Ancient Ecological Wisdom

Sri Lanka’s ancestors engineered tank cascades that regulated floods, stored water, and cooled microclimates. Forest belts protected valleys; sacred groves were biodiversity reservoirs. This policy revives those systems:

Restoring 10,000 hectares of tank ecosystems

Conserving coastal mangroves and reintroducing stone spillways

Integrating traditional seasonal calendars with AI forecasts

Recognising Vedda knowledge of climate shifts as part of national risk strategy

Our past and future must align, or both will be lost.

A Global Destination for Resilient Tourism

Climate-conscious travelers increasingly seek safe, secure, and sustainable destinations. Under this policy, Sri Lanka will position itself as the world’s first “climate-safe sanctuary island” — a place where:

Resorts are cyclone- and tsunami-resilient

Tourists receive live hazard updates via mobile apps

World Heritage Sites are protected by environmental buffers

Visitors can witness tank restoration, ancient climate engineering, and modern AI in action

Sri Lanka will invite scientists, startups, and resilience investors to join our innovation ecosystem — building eco-tourism that’s disaster-proof by design.

Resilience as a National Identity

This shift is not just about floods or cyclones. It is about redefining our identity. To be Sri Lankan must mean to live in harmony with nature and to be ready for its changes. Our ancestors did it. The science now supports it. The time has come.

Let us turn Sri Lanka into the world’s first climate-resilient heritage island — where ancient wisdom meets cutting-edge science, and every citizen stands protected under one shield: a disaster-proof nation.

Features

The minstrel monk and Rafiki the old mandrill in The Lion King – I

Why is national identity so important for a people? AI provides us with an answer worth understanding critically (Caveat: Even AI wisdom should be subjected to the Buddha’s advice to the young Kalamas):

‘A strong sense of identity is crucial for a people as it fosters belonging, builds self-worth, guides behaviour, and provides resilience, allowing individuals to feel connected, make meaningful choices aligned with their values, and maintain mental well-being even amidst societal changes or challenges, acting as a foundation for individual and collective strength. It defines “who we are” culturally and personally, driving shared narratives, pride, political action, and healthier relationships by grounding people in common values, traditions, and a sense of purpose.’

Ethnic Sinhalese who form about 75% of the Sri Lankan population have such a unique identity secured by the binding medium of their Buddhist faith. It is significant that 93% of them still remain Buddhist (according to 2024 statistics/wikipedia), professing Theravada Buddhism, after four and a half centuries of coercive Christianising European occupation that ended in 1948. The Sinhalese are a unique ancient island people with a 2500 year long recorded history, their own language and country, and their deeply evolved Buddhist cultural identity.

Buddhism can be defined, rather paradoxically, as a non-religious religion, an eminently practical ethical-philosophy based on mind cultivation, wisdom and universal compassion. It is an ethico-spiritual value system that prioritises human reason and unaided (i.e., unassisted by any divine or supernatural intervention) escape from suffering through self-realisation. Sri Lanka’s benignly dominant Buddhist socio-cultural background naturally allows unrestricted freedom of religion, belief or non-belief for all its citizens, and makes the country a safe spiritual haven for them. The island’s Buddha Sasana (Dispensation of the Buddha) is the inalienable civilisational treasure that our ancestors of two and a half millennia have bequeathed to us. It is this enduring basis of our identity as a nation which bestows on us the personal and societal benefits of inestimable value mentioned in the AI summary given at the beginning of this essay.

It was this inherent national identity that the Sri Lankan contestant at the 72nd Miss World 2025 pageant held in Hyderabad, India, in May last year, Anudi Gunasekera, proudly showcased before the world, during her initial self-introduction. She started off with a verse from the Dhammapada (a Pali Buddhist text), which she explained as meaning “Refrain from all evil and cultivate good”. She declared, “And I believe that’s my purpose in life”. Anudi also mentioned that Sri Lanka had gone through a lot “from conflicts to natural disasters, pandemics, economic crises….”, adding, “and yet, my people remain hopeful, strong, and resilient….”.

“Ayubowan! I am Anudi Gunasekera from Sri Lanka. It is with immense pride that I represent my Motherland, a nation of resilience, timeless beauty, and a proud history, Sri Lanka.

“I come from Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka’s first capital, and UNESCO World Heritage site, with its history and its legacy of sacred monuments and stupas…….”.

The “inspiring words” that Anudi quoted are from the Dhammapada (Verse 183), which runs, in English translation: “To avoid all evil/To cultivate good/and to cleanse one’s mind -/this is the teaching of the Buddhas”. That verse is so significant because it defines the basic ‘teaching of the Buddhas’ (i.e., Buddha Sasana; this is how Walpole Rahula Thera defines Buddha Sasana in his celebrated introduction to Buddhism ‘What the Buddha Taught’ first published in1959).

Twenty-five year old Anudi Gunasekera is an alumna of the University of Kelaniya, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in International Studies. She is planning to do a Master’s in the same field. Her ambition is to join the foreign service in Sri Lanka. Gen Z’er Anudi is already actively engaged in social service. The Saheli Foundation is her own initiative launched to address period poverty (i.e., lack of access to proper sanitation facilities, hygiene and health education, etc.) especially among women and post-puberty girls of low-income classes in rural and urban Sri Lanka.

Young Anudi is primarily inspired by her patriotic devotion to ‘my Motherland, a nation of resilience, timeless beauty, and a proud history, Sri Lanka’. In post-independence Sri Lanka, thousands of young men and women of her age have constantly dedicated themselves, oftentimes making the supreme sacrifice, motivated by a sense of national identity, by the thought ‘This is our beloved Motherland, these are our beloved people’.

The rescue and recovery of Sri Lanka from the evil aftermath of a decade of subversive ‘Aragalaya’ mayhem is waiting to be achieved, in every sphere of national engagement, including, for example, economics, communications, culture and politics, by the enlightened Anudi Gunasekeras and their male counterparts of the Gen Z, but not by the demented old stragglers lingering in the political arena listening to the unnerving rattle of “Time’s winged chariot hurrying near”, nor by the baila blaring monks at propaganda rallies.

Politically active monks (Buddhist bhikkhus) are only a handful out of the Maha Sangha (the general body of Buddhist bhikkhus) in Sri Lanka, who numbered just over 42,000 in 2024. The vast majority of monks spend their time quietly attending to their monastic duties. Buddhism upholds social and emotional virtues such as universal compassion, empathy, tolerance and forgiveness that protect a society from the evils of tribalism, religious bigotry and death-dealing religious piety.

Not all monks who express or promote political opinions should be censured. I choose to condemn only those few monks who abuse the yellow robe as a shield in their narrow partisan politics. I cannot bring myself to disapprove of the many socially active monks, who are articulating the genuine problems that the Buddha Sasana is facing today. The two bhikkhus who are the most despised monks in the commercial media these days are Galaboda-aththe Gnanasara and Ampitiye Sumanaratana Theras. They have a problem with their mood swings. They have long been whistleblowers trying to raise awareness respectively, about spreading religious fundamentalism, especially, violent Islamic Jihadism, in the country and about the vandalising of the Buddhist archaeological heritage sites of the north and east provinces. The two middle-aged monks (Gnanasara and Sumanaratana) belong to this respectable category. Though they are relentlessly attacked in the social media or hardly given any positive coverage of the service they are doing, they do nothing more than try to persuade the rulers to take appropriate action to resolve those problems while not trespassing on the rights of people of other faiths.

These monks have to rely on lay political leaders to do the needful, without themselves taking part in sectarian politics in the manner of ordinary members of the secular society. Their generally demonised social image is due, in my opinion, to three main reasons among others: 1) spreading misinformation and disinformation about them by those who do not like what they are saying and doing, 2) their own lack of verbal restraint, and 3) their being virtually abandoned to the wolves by the temporal and spiritual authorities.

(To be continued)

By Rohana R. Wasala ✍️

Features

US’ drastic aid cut to UN poses moral challenge to world

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

Considering that the US has hitherto been the UN’s biggest aid provider, it need hardly be said that the US decision would pose a daunting challenge to the UN’s humanitarian operations around the world. This would indeed mean that, among other things, people living in poverty and stifling material hardships, in particularly the Southern hemisphere, could dramatically increase. Coming on top of the US decision to bring to an end USAID operations, the poor of the world could be said to have been left to their devices as a consequence of these morally insensitive policy rethinks of the Trump administration.

Earlier, the UN had warned that it would be compelled to reduce its aid programs in the face of ‘the deepest funding cuts ever.’ In fact the UN is on record as requesting the world for $23bn for its 2026 aid operations.

If this UN appeal happens to go unheeded, the possibilities are that the UN would not be in a position to uphold the status it has hitherto held as the world’s foremost humanitarian aid provider. It would not be incorrect to state that a substantial part of the rationale for the UN’s existence could come in for questioning if its humanitarian identity is thus eroded.

Inherent in these developments is a challenge for those sections of the international community that wish to stand up and be counted as humanists and the ‘Conscience of the World.’ A responsibility is cast on them to not only keep the UN system going but to also ensure its increased efficiency as a humanitarian aid provider to particularly the poorest of the poor.

It is unfortunate that the US is increasingly opting for a position of international isolation. Such a policy position was adopted by it in the decades leading to World War Two and the consequences for the world as a result for this policy posture were most disquieting. For instance, it opened the door to the flourishing of dictatorial regimes in the West, such as that led by Adolph Hitler in Germany, which nearly paved the way for the subjugation of a good part of Europe by the Nazis.

If the US had not intervened militarily in the war on the side of the Allies, the West would have faced the distressing prospect of coming under the sway of the Nazis and as a result earned indefinite political and military repression. By entering World War Two the US helped to ward off these bleak outcomes and indeed helped the major democracies of Western Europe to hold their own and thrive against fascism and dictatorial rule.

Republican administrations in the US in particular have not proved the greatest defenders of democratic rule the world over, but by helping to keep the international power balance in favour of democracy and fundamental human rights they could keep under a tight leash fascism and linked anti-democratic forces even in contemporary times. Russia’s invasion and continued occupation of parts of Ukraine reminds us starkly that the democracy versus fascism battle is far from over.

Right now, the US needs to remain on the side of the rest of the West very firmly, lest fascism enjoys another unfettered lease of life through the absence of countervailing and substantial military and political power.

However, by reducing its financial support for the UN and backing away from sustaining its humanitarian programs the world over the US could be laying the ground work for an aggravation of poverty in the South in particular and its accompaniments, such as, political repression, runaway social discontent and anarchy.

What should not go unnoticed by the US is the fact that peace and social stability in the South and the flourishing of the same conditions in the global North are symbiotically linked, although not so apparent at first blush. For instance, if illegal migration from the South to the US is a major problem for the US today, it is because poor countries are not receiving development assistance from the UN system to the required degree. Such deprivation on the part of the South leads to aggravating social discontent in the latter and consequences such as illegal migratory movements from South to North.

Accordingly, it will be in the North’s best interests to ensure that the South is not deprived of sustained development assistance since the latter is an essential condition for social contentment and stable governance, which factors in turn would guard against the emergence of phenomena such as illegal migration.

Meanwhile, democratic sections of the rest of the world in particular need to consider it a matter of conscience to ensure the sustenance and flourishing of the UN system. To be sure, the UN system is considerably flawed but at present it could be called the most equitable and fair among international development organizations and the most far-flung one. Without it world poverty would have proved unmanageable along with the ills that come along with it.

Dehumanizing poverty is an indictment on humanity. It stands to reason that the world community should rally round the UN and ensure its survival lest the abomination which is poverty flourishes. In this undertaking the world needs to stand united. Ambiguities on this score could be self-defeating for the world community.

For example, all groupings of countries that could demonstrate economic muscle need to figure prominently in this initiative. One such grouping is BRICS. Inasmuch as the US and the West should shrug aside Realpolitik considerations in this enterprise, the same goes for organizations such as BRICS.

The arrival at the above international consensus would be greatly facilitated by stepped up dialogue among states on the continued importance of the UN system. Fresh efforts to speed-up UN reform would prove major catalysts in bringing about these positive changes as well. Also requiring to be shunned is the blind pursuit of narrow national interests.

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoGurusinha’s Boxing Day hundred celebrated in Melbourne

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoLeading the Nation’s Connectivity Recovery Amid Unprecedented Challenges

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoTime to close the Dickwella chapter

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoIt’s all over for Maxi Rozairo

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoEnvironmentalists warn Sri Lanka’s ecological safeguards are failing

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoDr. Bellana: “I was removed as NHSL Deputy Director for exposing Rs. 900 mn fraud”

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoDigambaram draws a broad brush canvas of SL’s existing political situation

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoDons on warpath over alleged undue interference in university governance