Features

The Energy Crisis hits the Kitchen

By Parakrama Jayasinghe

Past President Bio Energy Association of Sri Lanka

Close on the heels of the grave hit on the wallet of consumers due to the hefty hike in the LPG prices, a new crisis by way of safety of use of even the expensive gas has created an even greater problem. As recently as August 2021, I published an article titled. “Wallowing in the Fossil Fuel Trap” in The Island, where I dealt with the entire spectrum of energy,

While the impact on areas like electricity and transport fuels by this over-dependence on imported fossil fuels are kept under wraps by the authorities by high levels of subsidies, which keep the consumers in a state of false euphoria and leading them to believe that their interests are looked after and thus live in a fool’s paradise. But the present safety issue cannot be swept under the carpet.

For example, to cover the continuing losses by the CEB, running close to a hundred billion rupees in some years, even the consumers at the lowest consumption levels are paying an extra Rs. 5.00 or more per unit without it being reflected in the monthly bill. Perhaps, with one of the suppliers of LPG being a private company, the current LPG prices may not include any subsidies. Instead, the consumers are now in a worse situation when the very safety of use is in doubt.

The advent of LPG as a cooking fuel goes back to the 1970 decade when the LPG from our refinery was being flared off without any productive use. Limited to that level of availability and use, there can be no objection to this decision. The fault lies in expanding and promoting the use of LPG way beyond the local production possible from our refinery and resorting to imports over which we have absolutely no control.

This may have been an attractive commercial opportunity opening the way even for international petroleum giant, Shell, to move in. Let us not delve into the background and the later events which occurred. The fact remains that yet another import was promoted blindly with total lack of vision on the possible future impacts on many fronts. Our problems of shortage of foreign exchange was present even those days although not as critical as now.

The original price of LPG was Rs. 35.00 for a 13.5 kg cylinder has now ballooned up to Rs 2,850.00 for a 12.5 kg cylinder, an 88-fold increase.

Typical of the mindset of the Sri Lankan consumers, every time there is a price hike there will be protests and many high-level discussions and news reports, which fizzle out in a few weeks at most. The media shift their focus to the next crisis and the protesters would lose their audience and attention of the authorities. This is how the price of LPG has continually risen with the equally stupid occasional price reductions by the government trying to score a point, which are more than overridden by the next price hike.

Concentrating only on the present crisis on LPG, what is our alternative?

On some such occasions in the past in about year 2002 with a price hike, the NERD Centre embarked on a research project to develop a suitable wood fired cooking stove in an effort to entice the people to go back to the use of fuel wood. Several successful models were developed and licenses were issued to a number of companies to manufacture the units for the market. It was heartening to see those stoves being offered for reasonable prices in many hardware shops. The pictures below illustrate these models. (See figure 1)

However, as regrettably happens in Sri Lanka, this effort too fizzled out primarily due to Lack of development of a suitable supply mechanism for the fuel wood needed, particularly in the urban areas which could have gained the most from the adoption of the stoves.

Aggressive marketing of LPG was carried out even in the rural areas where the householders could have got all the fuelwood from their own backyard. We have calculated that the fuel wood needs of a family for the year could be generated continually from two rows of Gliricidia planted on the fence of a 10-perch block of land

Also on the background were the concerted efforts to downgrade and dissuade the use of biomass for cooking with references to widely cited academic theories and publications. The message being conveyed was that the use of biomass could lead to health hazards due to smoke and unburnt firewood, etc. We in Sri Lanka have used firewood and other biomass for cooking since time immemorial without any proven evidence of such health hazards. These problems may be true for some countries where cooking is done in poorly ventilated confined spaces. But not so for our traditional kitchens most of which also boast fireplaces with a chimney as part and parcel of the kitchen. The use of firewood in the traditional way could, of course, be problematic in the modern highrise apartments.

The vendors of LPG were quick to pounce upon these, and I remember a public seminar where some foreign agencies even offered the LPG cookers free of charge. They would not answer my question as to who will pay for the gas already on a rising price trend.

What are the alternatives available for us in the present context and how fast can they be adopted? I look at these in reference to the affordability and degree of sophistication that the consumer expects and is willing to pay for. Starting from the high end these can be listed as

1. Go electric – Before there are howls of protests, let me qualify this to say that this option is for those who already have their roof top solar PV systems of adequate capacity. As such, there would not be an additional burden on the national grid and the consumer would enjoy all the benefits of cooking with electricity while not feeling the financial pinch. Those who are aspiring to join the Surya Bala Sangraamya are well-advised to factor this in their assessment of capacity of the systems to be installed.

2. The NERD design of the wood stove, particularly the model with the electric fan performs satisfactorily and reliably. However, there are hardly any in the market while I understand that some licensees have re-commenced production. Also, the earlier problem of a reliable and sustainable supply of properly dried and processed fuelwood must be addressed along with the urgent action to accelerate the production of stoves. More players can join the manufacturing with the very likely rapid expansion of the demand.

3. The most convenient and immediately available option particularly for households in less urbanised areas, who were led astray by the authorities and the LPG vendors, is to adopt the much-improved covered clay stoves called the ‘Anagi Lipa’. As the name suggests it is a wonderful and simple invention which is available even in Colombo for a price of Rs 600.00 It has an efficiency of over three time that of a traditional three stone heath and thereby much reduced fuel wood consumption.

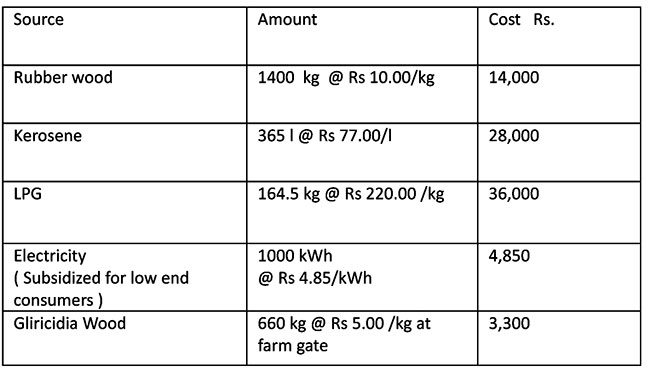

The chart indicates the relative cost of different fuel options. The electricity option is shown only for comparison as it is a zero cost for those who can afford a roof top solar PV system.

The question remains as to the means of ensuring a steady supply of fuel wood. As usual Sri Lanka has a viable indigenous solution for any problem, if only we are ready to appreciate and adopt them. In this case that wonder tree Gliricidia Sepium offers the obvious solution. The Cabinet of Ministers declared Gliricidia as the fourth national plantation crop as far back as June 2005 and promptly ignored all the proposals therein for the development of this valuable resource. Hopefully, they will wake up at least now and take action on those proposals which are even more valid now.

Moreover, the use of this option offers an added means of addressing a most aggravating problem faced by poor women, particularly in the rural areas, that of indebtedness to the micro finance companies and even some shylocks. Let them become the suppliers of the much needed fuel wood using their own Gliricidia trees, both for their own use and for sale to the more affluent housewives who are now unable to use LPG for safety reasons.

Fortunately, many rural families possess at least a quarter acre of land on which an adequate number of Gliricidia trees can be grown to provide them with the surplus wood for sale in addition to the income from creative use of the leaves. Thus, a steady cash income can be guaranteed while solving a national problem. There is no cost in the cultivation and the only investment required is for the purchase of a sharp machete. The chopped and dried wood can be market ready in say three-kilo packets in their spare time. However, the rest of the value chain and the systems to support this market must emerge.

In this light, it is worthwhile to consider the numbers involved. Sri Lanka imported $ 200 million worth of LPG last year. Even if 25 % of this amount can be redirected for the supply of Gliricidia fuelwood, a whopping Rs 10,000 million would flow to the rural economy.

So, it is up to the consumers themselves to make their own choices instead of forever depending on the authorities at all levels. Their willingness to change over is all that is needed to support the fuelwood suppliers.

Features

The call for review of reforms in education: discussion continues …

The hype around educational reforms has abated slightly, but the scandal of the reforms persists. And in saying scandal, I don’t mean the error of judgement surrounding a misprinted link of an online dating site in a Grade 6 English language text book. While that fiasco took on a nasty, undeserved attack on the Minister of Education and Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya, fundamental concerns with the reforms have surfaced since then and need urgent discussion and a mechanism for further analysis and action. Members of Kuppi have been writing on the reforms the past few months, drawing attention to the deeply troubling aspects of the reforms. Just last week, a statement, initiated by Kuppi, and signed by 94 state university teachers, was released to the public, drawing attention to the fundamental problems underlining the reforms https://island.lk/general-educational-reforms-to-what-purpose-a-statement-by-state-university-teachers/. While the furore over the misspelled and misplaced reference and online link raged in the public domain, there were also many who welcomed the reforms, seeing in the package, a way out of the bottle neck that exists today in our educational system, as regards how achievement is measured and the way the highly competitive system has not helped to serve a population divided by social class, gendered functions and diversities in talent and inclinations. However, the reforms need to be scrutinised as to whether they truly address these concerns or move education in a progressive direction aimed at access and equity, as claimed by the state machinery and the Minister… And the answer is a resounding No.

The hype around educational reforms has abated slightly, but the scandal of the reforms persists. And in saying scandal, I don’t mean the error of judgement surrounding a misprinted link of an online dating site in a Grade 6 English language text book. While that fiasco took on a nasty, undeserved attack on the Minister of Education and Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya, fundamental concerns with the reforms have surfaced since then and need urgent discussion and a mechanism for further analysis and action. Members of Kuppi have been writing on the reforms the past few months, drawing attention to the deeply troubling aspects of the reforms. Just last week, a statement, initiated by Kuppi, and signed by 94 state university teachers, was released to the public, drawing attention to the fundamental problems underlining the reforms https://island.lk/general-educational-reforms-to-what-purpose-a-statement-by-state-university-teachers/. While the furore over the misspelled and misplaced reference and online link raged in the public domain, there were also many who welcomed the reforms, seeing in the package, a way out of the bottle neck that exists today in our educational system, as regards how achievement is measured and the way the highly competitive system has not helped to serve a population divided by social class, gendered functions and diversities in talent and inclinations. However, the reforms need to be scrutinised as to whether they truly address these concerns or move education in a progressive direction aimed at access and equity, as claimed by the state machinery and the Minister… And the answer is a resounding No.

The statement by 94 university teachers deplores the high handed manner in which the reforms were hastily formulated, and without public consultation. It underlines the problems with the substance of the reforms, particularly in the areas of the structure of education, and the content of the text books. The problem lies at the very outset of the reforms, with the conceptual framework. While the stated conceptualisation sounds fancifully democratic, inclusive, grounded and, simultaneously, sensitive, the detail of the reforms-structure itself shows up a scandalous disconnect between the concept and the structural features of the reforms. This disconnect is most glaring in the way the secondary school programme, in the main, the junior and senior secondary school Phase I, is structured; secondly, the disconnect is also apparent in the pedagogic areas, particularly in the content of the text books. The key players of the “Reforms” have weaponised certain seemingly progressive catch phrases like learner- or student-centred education, digital learning systems, and ideas like moving away from exams and text-heavy education, in popularising it in a bid to win the consent of the public. Launching the reforms at a school recently, Dr. Amarasuriya says, and I cite the state-owned broadside Daily News here, “The reforms focus on a student-centered, practical learning approach to replace the current heavily exam-oriented system, beginning with Grade One in 2026 (https://www.facebook.com/reel/1866339250940490). In an address to the public on September 29, 2025, Dr. Amarasuriya sings the praises of digital transformation and the use of AI-platforms in facilitating education (https://www.facebook.com/share/v/14UvTrkbkwW/), and more recently in a slightly modified tone (https://www.dailymirror.lk/breaking-news/PM-pledges-safe-tech-driven-digital-education-for-Sri-Lankan-children/108-331699).

The idea of learner- or student-centric education has been there for long. It comes from the thinking of Paulo Freire, Ivan Illyich and many other educational reformers, globally. Freire, in particular, talks of learner-centred education (he does not use the term), as transformative, transformative of the learner’s and teacher’s thinking: an active and situated learning process that transforms the relations inhering in the situation itself. Lev Vygotsky, the well-known linguist and educator, is a fore runner in promoting collaborative work. But in his thought, collaborative work, which he termed the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) is processual and not goal-oriented, the way teamwork is understood in our pedagogical frameworks; marks, assignments and projects. In his pedagogy, a well-trained teacher, who has substantial knowledge of the subject, is a must. Good text books are important. But I have seen Vygotsky’s idea of ZPD being appropriated to mean teamwork where students sit around and carry out a task already determined for them in quantifying terms. For Vygotsky, the classroom is a transformative, collaborative place.

But in our neo liberal times, learner-centredness has become quick fix to address the ills of a (still existing) hierarchical classroom. What it has actually achieved is reduce teachers to the status of being mere cogs in a machine designed elsewhere: imitative, non-thinking followers of some empty words and guide lines. Over the years, this learner-centred approach has served to destroy teachers’ independence and agency in designing and trying out different pedagogical methods for themselves and their classrooms, make input in the formulation of the curriculum, and create a space for critical thinking in the classroom.

Thus, when Dr. Amarasuriya says that our system should not be over reliant on text books, I have to disagree with her (https://www.newsfirst.lk/2026/01/29/education-reform-to-end-textbook-tyranny ). The issue is not with over reliance, but with the inability to produce well formulated text books. And we are now privy to what this easy dismissal of text books has led us into – the rabbit hole of badly formulated, misinformed content. I quote from the statement of the 94 university teachers to illustrate my point.

“The textbooks for the Grade 6 modules . . . . contain rampant typographical errors and include (some undeclared) AI-generated content, including images that seem distant from the student experience. Some textbooks contain incorrect or misleading information. The Global Studies textbook associates specific facial features, hair colour, and skin colour, with particular countries and regions, and refers to Indigenous peoples in offensive terms long rejected by these communities (e.g. “Pygmies”, “Eskimos”). Nigerians are portrayed as poor/agricultural and with no electricity. The Entrepreneurship and Financial Literacy textbook introduces students to “world famous entrepreneurs”, mostly men, and equates success with business acumen. Such content contradicts the policy’s stated commitment to “values of equity, inclusivity and social justice” (p. 9). Is this the kind of content we want in our textbooks?”

Where structure is concerned, it is astounding to note that the number of subjects has increased from the previous number, while the duration of a single period has considerably reduced. This is markedly noticeable in the fact that only 30 hours are allocated for mathematics and first language at the junior secondary level, per term. The reduced emphasis on social sciences and humanities is another matter of grave concern. We have seen how TV channels and YouTube videos are churning out questionable and unsubstantiated material on the humanities. In my experience, when humanities and social sciences are not properly taught, and not taught by trained teachers, students, who will have no other recourse for related knowledge, will rely on material from controversial and substandard outlets. These will be their only source. So, instruction in history will be increasingly turned over to questionable YouTube channels and other internet sites. Popular media have an enormous influence on the public and shapes thinking, but a well formulated policy in humanities and social science teaching could counter that with researched material and critical thought. Another deplorable feature of the reforms lies in provisions encouraging students to move toward a career path too early in their student life.

The National Institute of Education has received quite a lot of flak in the fall out of the uproar over the controversial Grade 6 module. This is highlighted in a statement, different from the one already mentioned, released by influential members of the academic and activist public, which delivered a sharp critique of the NIE, even while welcoming the reforms (https://ceylontoday.lk/2026/01/16/academics-urge-govt-safeguard-integrity-of-education-reforms). The government itself suspended key players of the NIE in the reform process, following the mishap. The critique of NIE has been more or less uniform in our own discussions with interested members of the university community. It is interesting to note that both statements mentioned here have called for a review of the NIE and the setting up of a mechanism that will guide it in its activities at least in the interim period. The NIE is an educational arm of the state, and it is, ultimately, the responsibility of the government to oversee its function. It has to be equipped with qualified staff, provided with the capacity to initiate consultative mechanisms and involve panels of educators from various different fields and disciplines in policy and curriculum making.

In conclusion, I call upon the government to have courage and patience and to rethink some of the fundamental features of the reform. I reiterate the call for postponing the implementation of the reforms and, in the words of the statement of the 94 university teachers, “holistically review the new curriculum, including at primary level.”

(Sivamohan Sumathy was formerly attached to the University of Peradeniya)

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

By Sivamohan Sumathy

Features

Constitutional Council and the President’s Mandate

The Constitutional Council stands out as one of Sri Lanka’s most important governance mechanisms particularly at a time when even long‑established democracies are struggling with the dangers of executive overreach. Sri Lanka’s attempt to balance democratic mandate with independent oversight places it within a small but important group of constitutional arrangements that seek to protect the integrity of key state institutions without paralysing elected governments. Democratic power must be exercised, but it must also be restrained by institutions that command broad confidence. In each case, performance has been uneven, but the underlying principle is shared.

Comparable mechanisms exist in a number of democracies. In the United Kingdom, independent appointments commissions for the judiciary and civil service operate alongside ministerial authority, constraining but not eliminating political discretion. In Canada, parliamentary committees scrutinise appointments to oversight institutions such as the Auditor General, whose independence is regarded as essential to democratic accountability. In India, the collegium system for judicial appointments, in which senior judges of the Supreme Court play the decisive role in recommending appointments, emerged from a similar concern to insulate the judiciary from excessive political influence.

The Constitutional Council in Sri Lanka was developed to ensure that the highest level appointments to the most important institutions of the state would be the best possible under the circumstances. The objective was not to deny the executive its authority, but to ensure that those appointed would be independent, suitably qualified and not politically partisan. The Council is entrusted with oversight of appointments in seven critical areas of governance. These include the judiciary, through appointments to the Supreme Court and Court of Appeal, the independent commissions overseeing elections, public service, police, human rights, bribery and corruption, and the office of the Auditor General.

JVP Advocacy

The most outstanding feature of the Constitutional Council is its composition. Its ten members are drawn from the ranks of the government, the main opposition party, smaller parties and civil society. This plural composition was designed to reflect the diversity of political opinion in Parliament while also bringing in voices that are not directly tied to electoral competition. It reflects a belief that legitimacy in sensitive appointments comes not only from legal authority but also from inclusion and balance.

The idea of the Constitutional Council was strongly promoted around the year 2000, during a period of intense debate about the concentration of power in the executive presidency. Civil society organisations, professional bodies and sections of the legal community championed the position that unchecked executive authority had led to abuse of power and declining public trust. The JVP, which is today the core part of the NPP government, was among the political advocates in making the argument and joined the government of President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga on this platform.

The first version of the Constitutional Council came into being in 2001 with the 17th Amendment to the Constitution during the presidency of Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga. The Constitutional Council functioned with varying degrees of effectiveness. There were moments of cooperation and also moments of tension. On several occasions President Kumaratunga disagreed with the views of the Constitutional Council, leading to deadlock and delays in appointments. These experiences revealed both the strengths and weaknesses of the model.

Since its inception in 2001, the Constitutional Council has had its ups and downs. Successive constitutional amendments have alternately weakened and strengthened it. The 18th Amendment significantly reduced its authority, restoring much of the appointment power to the executive. The 19th Amendment reversed this trend and re-established the Council with enhanced powers. The 20th Amendment again curtailed its role, while the 21st Amendment restored a measure of balance. At present, the Constitutional Council operates under the framework of the 21st Amendment, which reflects a renewed commitment to shared decision making in key appointments.

Undermining Confidence

The particular issue that has now come to the fore concerns the appointment of the Auditor General. This is a constitutionally protected position, reflecting the central role played by the Auditor General’s Department in monitoring public spending and safeguarding public resources. Without a credible and fearless audit institution, parliamentary oversight can become superficial and corruption flourishes unchecked. The role of the Auditor General’s Department is especially important in the present circumstances, when rooting out corruption is a stated priority of the government and a central element of the mandate it received from the electorate at the presidential and parliamentary elections held in 2024.

So far, the government has taken hitherto unprecedented actions to investigate past corruption involving former government leaders. These actions have caused considerable discomfort among politicians now in the opposition and out of power. However, a serious lacuna in the government’s anti-corruption arsenal is that the post of Auditor General has been vacant for over six months. No agreement has been reached between the government and the Constitutional Council on the nominations made by the President. On each of the four previous occasions, the nominees of the President have failed to obtain its concurrence.

The President has once again nominated a senior officer of the Auditor General’s Department whose appointment was earlier declined by the Constitutional Council. The key difference on this occasion is that the composition of the Constitutional Council has changed. The three representatives from civil society are new appointees and may take a different view from their predecessors. The person appointed needs to be someone who is not compromised by long years of association with entrenched interests in the public service and politics. The task ahead for the new Auditor General is formidable. What is required is professional competence combined with moral courage and institutional independence.

New Opportunity

By submitting the same nominee to the Constitutional Council, the President is signaling a clear preference and calling it to reconsider its earlier decision in the light of changed circumstances. If the President’s nominee possesses the required professional qualifications, relevant experience, and no substantiated allegations against her, the presumption should lean toward approving the appointment. The Constitutional Council is intended to moderate the President’s authority and not nullify it.

A consensual, collegial decision would be the best outcome. Confrontational postures may yield temporary political advantage, but they harm public institutions and erode trust. The President and the government carry the democratic mandate of the people; this mandate brings both authority and responsibility. The Constitutional Council plays a vital oversight role, but it does not possess an independent democratic mandate of its own and its legitimacy lies in balanced, principled decision making.

Sri Lanka’s experience, like that of many democracies, shows that institutions function best when guided by restraint, mutual respect, and a shared commitment to the public good. The erosion of these values elsewhere in the world demonstrates their importance. At this critical moment, reaching a consensus that respects both the President’s mandate and the Constitutional Council’s oversight role would send a powerful message that constitutional governance in Sri Lanka can work as intended.

by Jehan Perera

Features

Gypsies … flying high

The scene has certainly changed for the Gypsies and today one could consider them as awesome crowd-pullers, with plenty of foreign tours, making up their itinerary.

The scene has certainly changed for the Gypsies and today one could consider them as awesome crowd-pullers, with plenty of foreign tours, making up their itinerary.

With the demise of Sunil Perera, music lovers believed that the Gypsies would find the going tough in the music scene as he was their star, and, in fact, Sri Lanka’s number one entertainer/singer,

Even his brother Piyal Perera, who is now in charge of the Gypsies, admitted that after Sunil’s death he was in two minds about continuing with the band.

However, the scene started improving for the Gypsies, and then stepped in Shenal Nishshanka, in December 2022, and that was the turning point,

With Shenal in their lineup, Piyal then decided to continue with the Gypsies, but, he added, “I believe I should check out our progress in the scene…one year at a time.”

The original Gypsies: The five brothers Lal, Nimal, Sunil, Nihal and Piyal

They had success the following year, 2023, and then decided that they continue in 2024, as well, and more success followed.

The year 2025 opened up with plenty of action for the band, including several foreign assignments, and 2026 has already started on an awesome note, with a tour of Australia and New Zealand, which will keep the Gypsies in that part of the world, from February to March.

Shenal has already turned out to be a great crowd puller, and music lovers in Australia and New Zealand can look forward to some top class entertainment from both Shenal and Piyal.

Piyal, who was not much in the spotlight when Sunil was in the scene, is now very much upfront, supporting Shenal, and they do an awesome job on stage … keeping the audience entertained.

Shenal is, in fact, a rocker, who plays the guitar, and is extremely creative on stage with his baila.

‘Api Denna’ Piyal and Shenal

Piyal and Shenal also move into action as a duo ‘Api Denna’ and have even done their duo scene abroad.

Piyal mentioned that the Gypsies will feature a female vocalist during their tour of New Zealand.

“With Monique Wille’s departure from the band, we now operate without a female vocalist, but if a female vocalist is required for certain events, we get a solo female singer involved, as a guest artiste. She does her own thing and we back her, and New Zealand requested for a female vocalist and Dilmi will be doing the needful for us,” said Piyal.

According to Piyal, he originally had plans to end the Gypsies in the year 2027 but with the demand for the Gypsies at a very high level now those plans may not work out, he says.

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoSri Lanka, the Stars,and statesmen

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoClimate risks, poverty, and recovery financing in focus at CEPA policy panel

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoHayleys Mobility ushering in a new era of premium sustainable mobility

-

Business21 hours ago

Business21 hours agoSLIM-Kantar People’s Awards 2026 to recognise Sri Lanka’s most trusted brands and personalities

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoAdvice Lab unveils new 13,000+ sqft office, marking major expansion in financial services BPO to Australia

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoArpico NextGen Mattress gains recognition for innovation

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoAltair issues over 100+ title deeds post ownership change

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoSri Lanka opens first country pavilion at London exhibition