Features

The build-up, 1962 coup d’etat, the aftermath and secret mission to London

Continuing Mrs. Bandaranaike’s first term as PM

(Excerpted from Rendering Unto Caesar, by Bradman Weerakoon)

Although her political aspiration was “to lighten the burden on the suffering masses” Sirimavo soon found that the economic realities would not allow her a free hand. In the early sixties the terms of trade, which had been favourable in the fifties, declined sharply. The Korean war boom had run its course. The rise in the price of tea had plateaued and the trend was now downwards. Our external assets were diminishing and when Felix became finance minister he had no alternative but to cut down on imports drastically.

Use of the scarce foreign exchange resource was controlled and foreign travel, education and medical treatment abroad were strictly limited. Tariffs were increased on a large number of items other than food, fertilizer and medicines and the import of private motor cars was totally banned. As the situation worsened textiles, motor car and bicycle tyres and even common household items like batteries for torches and blades for shaving were hard to come by. I found that a welcome gift for a friend, when you had a chance of going abroad, was to bring him back a packet of Wilkinson blades.

Sirimavo had also to face the rising costs of the social-welfare measures which could not be reduced, except at great political risk, and which ensured a reasonable level of nutrition, health and education to the mass of the people. This cushioning of the cost of living by the rice subsidy, free health services and free education was becoming harder to maintain with each passing year. Something had to give and Felix preparing for the 1963 July budget, proposed to the Cabinet a reduction in the rice ration per family. He had of course got Sirimavo’s nod for the proposal but it was opposed by the Government Parliamentary Group and led to Felix’s resignation a few days before budget day.

T B Ilangaratne, a Bandaranaike old-timer well to the left of the party, was hurriedly sworn in as finance minister and there was no cut in the ration when the speech was read out. Once again, as in Dudley’s time, rice and its price had become a potent political instrument. Felix was given the ministry of agriculture but not without a delay of about two months, when he would often sit at my desk in the Temple Trees office wondering when and which portfolio Sirimavo would give him this time.

Ethnic Politics

The Federal Party, which had voted to defeat Dudley’s minority UNP government at the vote on the ‘Throne speech in March 1960 gave its support to Sirimavo Bandaranaike and the SLFP in the July elections. In return the Federal Party expected some movement on the proposals made in the BC Pact which had been further elaborated in its Statement of Minimum Demands which had been put both to the UNP and the SLFP.

These referred to the four basic objectives of regional autonomy for the Northern and Eastern Provinces, suspension of state-aided colonization, Tamil language rights especially regarding entry of Tamil speaking persons to government service and amendments to the Citizenship Act of 1948 which had deprived thousands of up-country Tamils of their right to vote.

However, Sirimavo’s immediate priority concerns were elsewhere and had more to do with reviving the economy which was in decline. But her economic policies of increasing state control over the commanding heights of the economy while providing relief to the majority was of little help to the Tamils as the industrial enterprises were located mainly in the South and the preference for Sinhala language proficiency in the public sector did not enable the Tamils to reap any benefit from this policy.

The other strand of her policy of exercising more state control over education through the virtual take-over of the assisted schools also indirectly created resentment among the Tamil middle classes and the Tamil Christians. Education in the Jaffna peninsula – the heartland of the Tamils – was largely in the hands of missionary schools. Sirimavo although educated throughout her school career in mission schools – Ferguson College in Ratnapura in the primary classes and then St Bridget’s Convent, Colombo, a leading Roman Catholic institution, was to pursue a determined policy of bringing the assisted schools under state control and eliminating the difference which existed between the privileged and the well-endowed mission schools and the state-run schools.

Some of the leading schools which had opted to remain outside of the state system and be fee levying private institutions, continued but with the changes introduced by Sirimavo a large number of important schools, including her own St Bridget’s lost the grant-in-aid from the state which had enabled them to run without charging fees. These in future were to be under the direct control of the state as regards recruitment of staff and the content of the education they imparted.

Her education policy, which was seen as part of the socialist orientation of the government was much resented by powerful elites, especially in the city of Colombo and among the higher bureaucracy, which had largely been recruited from the leading public schools. It was to trigger one of the principal challenges Sirimavo had to face, the attempted coup d’etat in January 1962.

The state take-over of assisted schools meant that state patronage and financial assistance, extended from colonial times to schools run by religious denominations, would cease. This followed earlier moves to curtail the visas of the nursing nuns of the Catholic orders who had for many years been the mainstay of the country’s health institutions, particularly in the cities.

The prime mintilster’s permanent secretary in the ministry of defence and external affairs NQ (Neil Quintus) Dias was well-known for his strong stand against ‘Catholic Action’ as it was then called. His actions in regard to the defence establishment and police were also being watched by the upper echelons of the three forces which were then largely manned by non-Buddhist officers who had had their secondary education mainly, in the denominational schools.

As these actions of the government continued, and there rose an influential lobby against the schools’ take-over, an important religious dignitary, Ignatius Cardinal Gracias, came over from Bombay, in a hurried visit to talk to the prime minister. Although he was courteously received and given high hospitality, Sirimavo did not retract from the stand she had taken. The Cardinal returned to Bombay mission unaccomplished.

The seeming lack of interest by the administration to the problems of the Tamils, as articulated by the FP and put forward in the Minimum Demands, led to the FP calling for a non-violent hartal at its party convention in Jaffna in January 1962. On February 20, 1962, Chelvanayakam led the satyagraha by lying down on the floor in front of the entrance to the Jaffna kachcheri and blocking entry to it. This soon became a mass movement of defiance to government authority and when on April 14 a postal service was inaugurated by the Federal Party, the government moved to declare a state of emergency.

The armed forces were sent in, the satyagrahis were dispersed and the Federal Party members were arrested. The satyagraha had collapsed but its echoes and the images of a Sinhalese army in occupation of the ‘Tamil homeland’ began to reverberate and form the genesis of the militant movement which was to emerge later. Brigadier Richard Udugama, later to be Army Commander, was an important figure in the restoration of law and order in the North.

The January 1962 Abortive Coup d’etat

This was the troublesome background in which the coup d’etat by military and police high-ups was planned to take place on the night of January 27, 1962, a Saturday. I believe this date was chosen since the prime minister was scheduled to be at Kataragama for a pirith ceremony that evening.

According to the program prepared by her aide D P Amerasinghe, Sirimavo was to leave Colombo on Friday, attend the puja on Saturday night and return to Colombo on Sunday. This decision was made 10 days before the date of the planned coup. However, on seeing the program for Kataragama, I recalled that about a month earlier the prime minister had received a letter from the Chief Incumbent of the Getambe Temple (Peradeniya) inviting her to a ceremony there on the same night. Sirimavo had asked me to write to the priest saying that she was unable to accept the invitation as some urgent work compelled her to remain in Colombo that evening.

As soon as I realized that the dates were clashing I quickly pointed out to the prime minister that it would not be proper for her to go to Kataragama on the night of January 27 particularly since she had informed the Getambe Temple priest that she was forced to remain in Colombo for some urgent duty. I told her that when the priest read in the newspapers that she was at Kataragama on the 27th night it would create a bad impression in his mind about her credibility. Mrs Bandaranaik appreciated my point and asked Amerasinghe to cancel the Kataragama trip. The coup leaders had planned their strategy assuming that Sirimavo would be at Kataragama that night. If Sirimavo had, in fact gone to Kataragama the coup may well have succeeded.

Planning for the take-over of the government had gone on for quite some time by a very few at the top. Security precautions based on the principle of those who ‘need to know’ had been strictly observed. The detailed plans were revealed to most of those involved only less than 48 hours from ‘H’ hour.

Colonel Maurice de Mel and Colonel F C de Saram were in charge of army arrangements for the coup, while Sydney de Zoysa and C C Dissanayake were in charge of police arrangements. Royce de Mel former Captain of the Navy, was also associated in the detailed planning of the coup, and it seems that the co-ordination and army and police operations was undertaken by Sydney de Zoysa, a retired DIG of police.

F C (Derrick) de Saram, was a key figure and wanted to ‘take the rap’ as he put it for the attempted coup. On hearing that something was seriously amiss that Sunday morning I reported to Sirimavo and Felix who were already at work at Temple Trees. F C de Saram, smartly turned out in his Colonel’s uniform – he was in the volunteer corps – and as usual, cheerful and confident, was at the front porch around 9.00 am. On my inquiring what was up since I was quite unaware of the night’s happenings, grinning broadly he replied breezily that there was some small matter which had come up on which he was wanted and went upstairs to where Felix had set up an investigating unit. I did not see him again until he was released from prison four years later.

Derrick was connected to the Bandaranaike family through marriage to an Obeysekere. He was a highly talented and popular figure with many sides to his character. I knew him well and admired him for his sportsmanship and his outstanding leadership for the Sinhalese Sports Club and his captaincy of All Ceylon at cricket. I did not realize that he had political sensitivities of any kind, until one evening after ‘nets’ at the SSC, he engaged me in a long conversation about his Oxford days and the part he had played in the agitation for Indian independence in the Indian Majlis — a vibrant agitational group at the time, in England. The conversation turned soon to the Sirimavo government’s socialist programs and the disastrous effect it was having on the country. I felt he was trying to draw me out and therefore, was cautious in my response.

As more and more military officers, many of them my acquaintances of the sports field, came in, the magnitude and widespread nature of the attempted coup came into focus. All of the Ministers of the Government, the Permanent Secretary for Defence and External Affairs, the Inspector-General of Police, the Deputy Inspector-General in charge of the Criminal Investigation Department, and some leftist leaders were among the persons to be arrested at some time after midnight on the 27th. The acting Captain of the Navy, Rajan Kadirgamar was also marked for arrest, while the other service commanders were to be restrained, and prevented from leaving their houses that night after a certain hour.

The persons arrested in Colombo were to be taken to army headquarters and imprisoned in the Ammunition Magazine, which is a reinforced concrete structure, partially underground. Those arrested outside Colombo were to be taken to the police headquarters of the area pending further instructions.

Soon after midnight, police cars equipped with radio and loud hailers were to be sent out to announce an immediate curfew in the city of Colombo.

As more and more details were revealed with the younger officers making long confessions” hoping that this would earn them a pardon, Felix tightened security and threw a cordon around Temple Trees. That evening I saw Rajan Kadirgamar dressed in blue battledress, toting a sub-machine gun and prowling up and down the front corridor. As he put it he was out there because no one knew, as of then, who was in and who was not and whether the coup was still on.

The atmosphere was very, very tense. Felix was in his element getting all the facts of the case and breaking down the evidence of those who tried to downplay what the plotters were doing on the Saturday night. They, the plotters were trying to make out that all they intended to do was a full dress rehearsal, to deal with an imminent breakdown of law and order that, they, the military top brass wished to avert in the national interest.

A feature of the investigation was the work of the DIG, CID, S A Dissanayake, the brother of C C Dissanayake, one of the chief suspects. The brothers had joined the force together as assistant superintendents, had been excellent policemen throughout and were competitive rivals. Blood was certainly not going to stand in the way of duty and Jingle (S A) was assiduous in unearthing fresh evidence against Jungle (C C) his own brother. This duty consciousness, in which duty transcended blood relationship, was perhaps part of a colonial inheritance, which is unheard of today.

Based on the facts revealed during the investigations, which were being conveyed to her each day, the prime minister was quick to act. Speedy changes were made in certain key positions in the armed forces and police. The attorney-general was consulted regarding the possibility of new laws to prosecute the plotters since existing legislation and procedures might be insufficient to deal with the case, and since there had been several references in the statements to the possible involvement of the Governor-General Oliver Goonetilleke, action to neutralize and remove him from office had to be effected as soon as possible.

Finally, the Cabinet decided to formulate new legislation to proceed with the case against 29 suspects. But this itself contained the seeds of failure. After conviction by the courts in Ceylon, the Privy Council to which the case was appealed proceeded to rule in favour of the accused now in remand on the grounds that the legislation was ultra vires to the Constitution. The defence had successfully pleaded the ground of the retroactive nature of the law and the Privy Council, the final court of appeal at the time had held with the appellants. The Privy Council judgment was delivered after the UNP had come back in 1965 and the government was not inclined to go any further. Whereupon those who had now spent around four years in detention and remand prison returned home and continued albeit at a lower profile to pursue their normal avocations both on the sports fields and in civil society.

As for the other line of action against the governor-general, this required two sets of measures. Firstly, informing the Queen since the governor-general was her appointee although the prime minister made the recommendation in the first instance. Secondly, to find a suitable alternative in case the Queen was prepared to drop Sir Oliver. There was fortunately for Sirimavo an appropriate candidate in William Gopallawa, then Ambassador in Washington. In Bandaranaike’s time Gopallawa who had been municipal commissioner of Kandy had been brought to Colombo as commissioner. Later he had been appointed Ambassador to China and thereafter in Sirimavo’s time Ambassador to Washington.

There had been some comment in the gossip columns of the weeklies that these appointments smacked of a little family bandyism since Gopallawa was the father-in-law of Mackie, Sirimavo’s brother. However, Bandaranaike had shrugged this off as Gopallawa had proved himself an efficient and clean municipal commissioner and a cautious and loyal ambassador and although not holding a particularly distinguished public service record, was fully eligible for the highest position in the political hierarchy.

On February 18, 1962 Felix Dias Bandaranaike made a statement in the House of Representatives and said that during the investigations of the attempted coup, the name of Sir Oliver Goonetilleke too had been mentioned. Sir Oliver indicated that he had no objection to being questioned like any other citizen. However, nobody had the power to question the duly appointed representative of the Queen without obtaining her permission.

I was sent on a secret mission to London – to see the Queen

One morning when I went to office, Sirimavo asked me to fly to London immediately with a ‘dangerous’ letter. I packed a suitcase and left for London in a hurry.Suffice it to say that when I returned to Ceylon after a week’s stay in London my mission had proved a success.

On the afternoon of February 26, 1962, we informed all newspaper offices and Radio Ceylon to stand by for a very important announcement to be released at midnight. Accordingly, Radio Ceylon too extended night transmissions beyond the normal closing times.

The announcement made under the name of Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike was broadcast at 12 midnight. It said that Her Majesty, the Queen of England, had kindly consented to a proposal made by the Queen’s Government in Ceylon to appoint Mr William Gopallawa as the governor-general of Ceylon to succeed Sir Oliver Goonetilleke. The appointment was to be effective from March 20, 1962, the announcement added. At the same time a similar announcement was made by Buckingham Palace, in London.

Features

An innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

After nearly two decades of on-and-off negotiations that began in 2007, India and the European Union formally finally concluded a comprehensive free trade agreement on 27 January 2026. This agreement, the India–European Union Free Trade Agreement (IEUFTA), was hailed by political leaders from both sides as the “mother of all deals,” because it would create a massive economic partnership and greatly increase the current bilateral trade, which was over US$ 136 billion in 2024. The agreement still requires ratification by the European Parliament, approval by EU member states, and completion of domestic approval processes in India. Therefore, it is only likely to come into force by early 2027.

An Innocent Bystander

When negotiations for a Free Trade Agreement between India and the European Union were formally launched in June 2007, anticipating far-reaching consequences of such an agreement on other developing countries, the Commonwealth Secretariat, in London, requested the Centre for Analysis of Regional Integration at the University of Sussex to undertake a study on a possible implication of such an agreement on other low-income developing countries. Thus, a group of academics, led by Professor Alan Winters, undertook a study, and it was published by the Commonwealth Secretariat in 2009 (“Innocent Bystanders—Implications of the EU-India Free Trade Agreement for Excluded Countries”). The authors of the study had considered the impact of an EU–India Free Trade Agreement for the trade of excluded countries and had underlined, “The SAARC countries are, by a long way, the most vulnerable to negative impacts from the FTA. Their exports are more similar to India’s…. Bangladesh is most exposed in the EU market, followed by Pakistan and Sri Lanka.”

Trade Preferences and Export Growth

Normally, reduction of price through preferential market access leads to export growth and trade diversification. During the last 19-year period (2015–2024), SAARC countries enjoyed varying degrees of preferences, under the EU’s Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP). But, the level of preferential access extended to India, through the GSP (general) arrangement, only provided a limited amount of duty reduction as against other SAARC countries, which were eligible for duty-free access into the EU market for most of their exports, via their LDC status or GSP+ route.

However, having preferential market access to the EU is worthless if those preferences cannot be utilised. Sri Lanka’s preference utilisation rate, which specifies the ratio of eligible to preferential imports, is significantly below the average for the EU GSP receiving countries. It was only 59% in 2023 and 69% in 2024. Comparative percentages in 2024 were, for Bangladesh, 96%; Pakistan, 95%; and India, 88%.

As illustrated in the table above, between 2015 and 2024, the EU’s imports from SAARC countries had increased twofold, from US$ 63 billion in 2015 to US$ 129 billion by 2024. Most of this growth had come from India. The imports from Pakistan and Bangladesh also increased significantly. The increase of imports from Sri Lanka, when compared to other South Asian countries, was limited. Exports from other SAARC countries—Afghanistan, Bhutan, Nepal, and the Maldives—are very small and, therefore, not included in this analysis.

Why the EU – India FTA?

With the best export performance in the region, why does India need an FTA with the EU?

Because even with very impressive overall export growth, in certain areas, India has performed very poorly in the EU market due to tariff disadvantages. In addition to that, from January 2026, the EU has withdrawn GSP benefits from most of India’s industrial exports. The FTA clearly addresses these challenges, and India will improve her competitiveness significantly once the FTA becomes operational.

Then the question is, what will be its impact on those “innocent bystanders” in South Asia and, more particularly, on Sri Lanka?

To provide a reasonable answer to this question, one has to undertake an in-depth product-by-product analysis of all major exports. Due to time and resource constraints, for the purpose of this article, I took a brief look at Sri Lanka’s two largest exports to the EU, viz., the apparels and rubber-based products.

Fortunately, Sri Lanka’s exports of rubber products will be only nominally impacted by the FTA due to the low MFN duty rate. For example, solid tyres and rubber gloves are charged very low (around 3%) MFN duty and the exports of these products from Sri Lanka and India are eligible for 0% GSP duty at present. With an equal market access, Sri Lanka has done much better than India in the EU market. Sri Lanka is the largest exporter of solid tyres to the EU and during 2024 our exports were valued at US$180 million.

On the other hand, Tariffs MFN tariffs on Apparel at 12% are relatively high and play a big role in apparel sourcing. Even a small difference in landed cost can shift entire sourcing to another supplier country. Indian apparel exports to the EU faced relatively high duties (8.5% – 12%), while competitors, such as Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, are eligible for preferential access. In addition to that, Bangladesh enjoys highly favourable Rules of Origin in the EU market. The impact of these different trade rules, on the EU’s imports, is clearly visible in the trade data.

During the last 10 years (2015-2024), the EU’s apparel imports from Bangladesh nearly doubled, from US$15.1 billion, in 2015, to US$29.1 billion by 2024, and apparel imports from Pakistan more than doubled, from US$2.3 billion to US$5.5 billion. However, apparel imports from Sri Lanka increased only from US$1.3 billion in 2015 to US$2.2 billion by 2024. The impressive export growth from Pakistan and Bangladesh is mostly related to GSP preferences, while the lackluster growth of Sri Lankan exports was largely due to low preference utilisation. Nearly half of Sri Lanka’s apparel exports faced a 12% tariff due to strict Rules of Origin requirements to qualify for GSP.

During the same period, the EU’s apparel imports from India only showed very modest growth, from US$ 5.3 billion, in 2015, to US$ 6.3 billion in 2024. The main reason for this was the very significant tariff disadvantage India faced in the EU market. However, once the FTA eliminates this gap, apparel imports from India are expected to grow rapidly.

According to available information, Indian industry bodies expect US$ 5-7 billion growth of textiles and apparel exports during the first three years of the FTA. This will create a significant trade diversion, resulting in a decline in exports from China and other countries that do not enjoy preferential market access. As almost half of Sri Lanka’s apparel exports are not eligible for GSP, the impact on our exports will also be fierce. Even in the areas where Sri Lanka receives preferential duty-free access, the arrival of another large player will change the market dynamics greatly.

A Passive Onlooker?

Since the commencement of the negotiations on the EU–India FTA, Bangladesh and Pakistan have significantly enhanced the level of market access through proactive diplomatic interventions. As a result, they have substantially increased competitiveness and the market share within the EU. This would help them to minimize the adverse implications of the India–EU FTA on their exports. Sri Lanka’s exports to the EU market have not performed that well. The challenges in that market will intensify after 2027.

As we can clearly anticipate a significant adverse impact from the EU-India FTA, we should start to engage immediately with the European Commission on these issues without being passive onlookers. For example, the impact of the EU-India FTA should have been a main agenda item in the recently concluded joint commission meeting between the European Commission and Sri Lanka in Colombo.

Need of the Hour – Proactive Commercial Diplomacy

In the area of international trade, it is a time of turbulence. After the US Supreme Court judgement on President Trump’s “reciprocal tariffs,” the only prediction we can make about the market in the United States market is its continued unpredictability. India concluded an FTA with the UK last May and now the EU-India FTA. These are Sri Lanka’s largest markets. Now to navigate through these volatile, complex, and rapidly changing markets, we need to move away from reactive crisis management mode to anticipatory action. Hence, proactive commercial diplomacy is the need of the hour.

(The writer can be reached at senadhiragomi@gmail.com)

By Gomi Senadhira

Features

Educational reforms: A perspective

Dr. B.J.C. Perera (Dr. BJCP) in his article ‘The Education cross roads: Liberating Sri Lankan classroom and moving ahead’ asks the critical question that should be the bedrock of any attempt at education reform – ‘Do we truly and clearly understand how a human being learns? (The Island, 16.02.2026)

Dr. BJCP describes the foundation of a cognitive architecture taking place with over a million neural connections occurring in a second. This in fact is the result of language learning and not the process. How do we ‘actually’ learn and communicate with one another? Is a question that was originally asked by Galileo Galilei (1564 -1642) to which scientists have still not found a definitive answer. Naom Chomsky (1928-) one of the foremost intellectuals of our time, known as the father of modern linguistics; when once asked in an interview, if there was any ‘burning question’ in his life that he would have liked to find an answer for; commented that this was one of the questions to which he would have liked to find the answer. Apart from knowing that this communication takes place through language, little else is known about the subject. In this process of learning we learn in our mother tongue and it is estimated that almost 80% of our learning is completed by the time we are 5 years old. It is critical to grasp that this is the actual process of learning and not ‘knowledge’ which tends to get confused as ‘learning’. i.e. what have you learnt?

The term mother tongue is used here as many of us later on in life do learn other languages. However, there is a fundamental difference between these languages and one’s mother tongue; in that one learns the mother tongue- and how that happens is the ‘burning question’ as opposed to a second language which is taught. The fact that the mother tongue is also formally taught later on, does not distract from this thesis.

Almost all of us take the learning of a mother tongue for granted, as much as one would take standing and walking for granted. However, learning the mother tongue is a much more complex process. Every infant learns to stand and walk the same way, but every infant depending on where they are born (and brought up) will learn a different mother tongue. The words that are learnt are concepts that would be influenced by the prevalent culture, religion, beliefs, etc. in that environment of the child. Take for example the term father. In our culture (Sinhala/Buddhist) the father is an entity that belongs to himself as well as to us -the rest of the family. We refer to him as ape thaththa. In the English speaking (Judaeo-Christian) culture he is ‘my father’. ‘Our father’ is a very different concept. ‘Our father who art in heaven….

All over the world education is done in one’s mother tongue. The only exception to this, as far as I know, are the countries that have been colonised by the British. There is a vast amount of research that re-validates education /learning in the mother tongue. And more to the point, when it comes to the comparability of learning in one’s own mother tongue as opposed to learning in English, English fails miserably.

Education /learning is best done in one’s mother tongue.

This is a fact. not an opinion. Elegantly stated in the words of Prof. Tove Skutnabb-Kangas-“Mother tongue medium education is controversial, but ‘only’ politically. Research evidence about it is not controversial.”

The tragedy is that we are discussing this fundamental principle that is taken for granted in the rest of the world. It would not be not even considered worthy of a school debate in any other country. The irony of course is, that it is being done in English!

At school we learnt all of our subjects in Sinhala (or Tamil) right up to University entrance. Across the three streams of Maths, Bio and Commerce, be it applied or pure mathematics, physics, chemistry, zoology, botany economics, business, etc. Everything from the simplest to the most complicated concept was learnt in our mother tongue. An uninterrupted process of learning that started from infancy.

All of this changed at university. We had to learn something new that had a greater depth and width than anything we had encountered before in a language -except for a very select minority – we were not at all familiar with. There were students in my university intake that had put aside reading and writing, not even spoken English outside a classroom context. This I have been reliably informed is the prevalent situation in most of the SAARC countries.

The SAARC nations that comprise eight countries (Sri Lanka, Maldives, India, Pakistan Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Bhutan) have 21% of the world population confined to just 3% of the earth’s land mass making it probably one of the most densely populated areas in the world. One would assume that this degree of ‘clinical density’ would lead to a plethora of research publications. However, the reality is that for 25 years from 1996 to 2021 the contribution by the SAARC nations to peer reviewed research in the field of Orthopaedics and Sports medicine- my profession – was only 1.45%! Regardless of each country having different mother tongues and vastly differing socio-economic structures, the common denominator to all these countries is that medical education in each country is done in a foreign language (English).

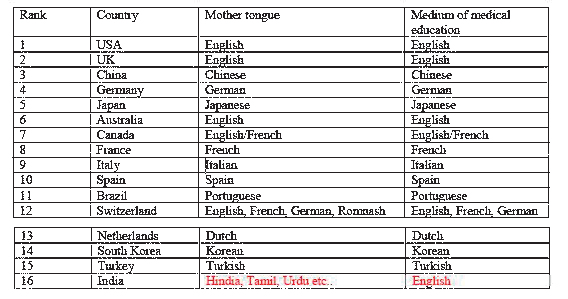

The impact of not learning in one’s mother tongue can be illustrated at a global level. This can be easily seen when observing the research output of different countries. For example, if one looks at orthopaedics and sports medicine (once again my given profession for simplicity); Table 1. shows the cumulative research that has been published in peer review journals. Despite now having the highest population in the world, India comes in at number 16! It has been outranked by countries that have a population less than one of their states. Pundits might argue giving various reasons for this phenomenon. But the inconvertible fact remains that all other countries, other than India, learn medicine in their mother tongue.

(See Table 1) Mother tongue, medium of education in country rank order according to the volume of publications of orthopaedics and sports medicine in peer reviewed journals 1996 to 2024. Source: Scimago SCImago journal (https://www.scimagojr.com/) has collated peer review journal publications of the world. The publications are categorized into 27 categories. According to the available data from 1996 to 2024, China is ranked the second across all categories with India at the 6th position. China is first in chemical engineering, chemistry, computer science, decision sciences, energy, engineering, environmental science, material sciences, mathematics, physics and astronomy. There is no subject category that India is the first in the world. China ranks higher than India in all categories except dentistry.

The reason for this difference is obvious when one looks at how learning is done in China and India.

The Chinese learn in their mother tongue. From primary to undergraduate and postgraduate levels, it is all done in Chinese. Therefore, they have an enormous capacity to understand their subject matter just not itself, but also as to how it relates to all other subjects/ themes that surround it. It is a continuous process of learning that evolves from infancy onwards, that seamlessly passes through, primary, secondary, undergraduate and post graduate education, research, innovation, application etc. Their social language is their official language. The language they use at home is the language they use at their workplaces, clubs, research facilities and so on.

In India higher education/learning is done in a foreign language. Each state of India has its own mother tongue. Be it Hindi, Tamil, Urdu, Telagu, etc. Infancy, childhood and school education to varying degrees is carried out in each state according to their mother tongue. Then, when it comes to university education and especially the ‘science subjects’ it takes place in a foreign tongue- (English). English remains only as their ‘research’ language. All other social interactions are done in their mother tongue.

India and China have been used as examples to illustrate the point between learning in the mother tongue and a foreign tongue, as they are in population terms comparable countries. The unpalatable truth is that – though individuals might have a different grasp of English- as countries, the ability of SAARC countries to learn and understand a subject in a foreign language is inferior to the rest of the world that is learning the same subject in its mother tongue. Imagine the disadvantage we face at a global level, when our entire learning process across almost all disciplines has been in a foreign tongue with comparison to the rest of the world that has learnt all these disciplines in their mother tongue. And one by-product of this is the subsequent research, innovation that flows from this learning will also be inferior to the rest of the world.

All this only confirms what we already know. Learning is best done in one’s mother tongue! .

What needs to be realised is that there is a critical difference between ‘learning English’ and ‘learning in English’. The primary-or some may argue secondary- purpose of a university education is to learn a particular discipline, be it medicine, engineering, etc. The students- have been learning everything up to that point in Sinhala or Tamil. Learning their discipline in their mother tongue will be the easiest thing for them. The solution to this is to teach in Sinhala or Tamil, so it can be learnt in the most efficient manner. Not to lament that the university entrant’s English is poor and therefore we need to start teaching English earlier on.

We are surviving because at least up to the university level we are learning in the best possible way i.e. in our mother tongue. Can our methods be changed to be more efficient? definitely. If, however, one thinks that the answer to this efficient change in the learning process is to substitute English for the mother tongue, it will defeat the very purpose it is trying to overcome. According to Dr. BJCP as he states in his article; the current reforms of 2026 for the learning process for the primary years, centre on the ‘ABCDE’ framework: Attendance, Belongingness, Cleanliness, Discipline and English. Very briefly, as can be seen from the above discussion, if this is the framework that is to be instituted, we should modify it to ABCDEF by adding a F for Failure, for completeness!

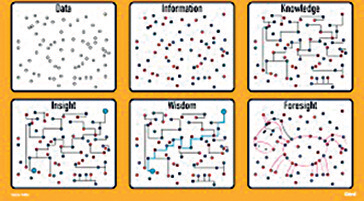

(See Figure 1) The components and evolution of learning: Data, information, knowledge, insight, wisdom, foresight As can be seen from figure 1. data and information remain as discrete points. They do not have interconnections between them. It is these subsequent interconnections that constitute learning. And these happen best through the mother tongue. Once again, this is a fact. Not an opinion. We -all countries- need to learn a second language (foreign tongue) in order to gather information and data from the rest of the world. However, once this data/ information is gathered, the learning needs to happen in our own mother tongue.

Without a doubt English is the most universally spoken language. It is estimated that almost a quarter of the world speaks English as its mother tongue or as a second language. I am not advocating to stop teaching English. Please, teach English as a second language to give a window to the rest of the world. Just do not use it as the mode of learning. Learn English but do not learn in English. All that we will be achieving by learning in English, is to create a nation of professionals that neither know English well nor their subject matter well.

If we are to have any worthwhile educational reforms this should be the starting pivotal point. An education that takes place in one’s mother tongue. Not instituting this and discussing theories of education and learning and proposing reforms, is akin to ‘rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic’. Sadly, this is not some stupendous, revolutionary insight into education /learning. It is what the rest of the world has been doing and what we did till we came under British rule.

Those who were with me in the medical faculty may remember that I asked this question then: Why can’t we be taught in Sinhala? Today, with AI, this should be much easier than what it was 40 years ago.

The editorial of this newspaper has many a time criticised the present government for its lackadaisical attitude towards bringing in the promised ‘system change’. Do this––make mother tongue the medium of education /learning––and the entire system will change.

by Dr. Sumedha S. Amarasekara

Features

Ukraine crisis continuing to highlight worsening ‘Global Disorder’

The world has unhappily arrived at the 4th anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and as could be seen a resolution to the long-bleeding war is nowhere in sight. In fact the crisis has taken a turn for the worse with the Russian political leadership refusing to see the uselessness of its suicidal invasion and the principal power groupings of the West even more tenaciously standing opposed to the invasion.

The world has unhappily arrived at the 4th anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and as could be seen a resolution to the long-bleeding war is nowhere in sight. In fact the crisis has taken a turn for the worse with the Russian political leadership refusing to see the uselessness of its suicidal invasion and the principal power groupings of the West even more tenaciously standing opposed to the invasion.

One fatal consequence of the foregoing trends is relentlessly increasing ‘Global Disorder’ and the heightening possibility of a regional war of the kind that broke out in Europe in the late thirties at the height of Nazi dictator Adolph Hitler’s reckless territorial expansions. Needless to say, that regional war led to the Second World War. As a result, sections of world opinion could not be faulted for believing that another World War is very much at hand unless peace making comes to the fore.

Interestingly, the outbreak of the Second World War coincided with the collapsing of the League of Nations, which was seen as ineffective in the task of fostering and maintaining world law and order and peace. Needless to say, the ‘League’ was supplanted by the UN and the question on the lips of the informed is whether the fate of the ‘League’ would also befall the UN in view of its perceived inability to command any authority worldwide, particularly in the wake of the Ukraine blood-letting.

The latter poser ought to remind the world that its future is gravely at risk, provided there is a consensus among the powers that matter to end the Ukraine crisis by peaceful means. The question also ought to remind the world of the urgency of restoring to the UN system its authority and effectiveness. The spectre of another World War could not be completely warded off unless this challenge is faced and resolved by the world community consensually and peacefully.

It defies comprehension as to why the Russian political leadership insists on prolonging the invasion, particularly considering the prohibitive human costs it is incurring for Russia. There is no sign of Ukraine caving-in to Russian pressure on the battle field and allowing Russia to have its own way and one wonders whether Ukraine is going the way of Afghanistan for Russia. If so the invasion is an abject failure.

The Russian political leadership would do well to go for a negotiated settlement and thereby ensure peace for the Russian people, Ukraine and the rest of Europe. By drawing on the services of the UN for this purpose, Russian political leaders would be restoring to the UN its dignity and rightful position in the affairs of the world.

Russia, meanwhile, would also do well not to depend too much on the Trump administration to find a negotiated end to the crisis. This is in view of the proved unreliability of the Trump government and the noted tendency of President Trump to change his mind on questions of the first importance far too frequently. Against this backdrop the UN would prove the more reliable partner to work with.

While there is no sign of Russia backing down, there are clearly no indications that going forward Russia’s invasion would render its final aims easily attainable either. Both NATO and the EU, for example, are making it amply clear that they would be staunchly standing by Ukraine. That is, Ukraine would be consistently armed and provided for in every relevant respect by these Western formations. Given these organizations’ continuing power it is difficult to see Ukraine being abandoned in the foreseeable future.

Accordingly, the Ukraine war would continue to painfully grind on piling misery on the Ukraine and Russian people. There is clearly nothing in this war worth speaking of for the two peoples concerned and it will be an action of the profoundest humanity for the Russian political leadership to engage in peace talks with its adversaries.

It will be in order for all countries to back a peaceful solution to the Ukraine nightmare considering that a continued commitment to the UN Charter would be in their best interests. On the question of sovereignty alone Ukraine’s rights have been grossly violated by Russia and it is obligatory on the part of every state that cherishes its sovereignty to back Ukraine to the hilt.

Barring a few, most states of the West could be expected to be supportive of Ukraine but the global South presents some complexities which get in the way of it standing by the side of Ukraine without reservations. One factor is economic dependence on Russia and in these instances countries’ national interests could outweigh other considerations on the issue of deciding between Ukraine and Russia. Needless to say, there is no easy way out of such dilemmas.

However, democracies of the South would have no choice but to place principle above self interest and throw in their lot with Ukraine if they are not to escape the charge of duplicity, double talk and double think. The rest of the South, and we have numerous political identities among them, would do well to come together, consult closely and consider as to how they could collectively work towards a peaceful and fair solution in Ukraine.

More broadly, crises such as that in Ukraine, need to be seen by the international community as a challenge to its humanity, since the essential identity of the human being as a peacemaker is being put to the test in these prolonged and dehumanizing wars. Accordingly, what is at stake basically is humankind’s fundamental identity or the continuation of civilization. Put simply, the choice is between humanity and barbarity.

The ‘Swing States’ of the South, such as India, Indonesia, South Africa and to a lesser extent Brazil, are obliged to put their ‘ best foot forward’ in these undertakings of a potentially historic nature. While the humanistic character of their mission needs to be highlighted most, the economic and material costs of these wasting wars, which are felt far and wide, need to be constantly focused on as well.

It is a time to protect humanity and the essential principles of democracy. It is when confronted by the magnitude and scale of these tasks that the vital importance of the UN could come to be appreciated by human kind. This is primarily on account of the multi-dimensional operations of the UN. The latter would prove an ideal companion of the South if and when it plays the role of a true peace maker.

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoReconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoVictor Melder turns 90: Railwayman and bibliophile extraordinary

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoLOVEABLE BUT LETHAL: When four-legged stars remind us of a silent killer

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoVictor, the Friend of the Foreign Press

-

Latest News6 days ago

Latest News6 days agoNew Zealand meet familiar opponents Pakistan at spin-friendly Premadasa

-

Latest News6 days ago

Latest News6 days agoECB push back at Pakistan ‘shadow-ban’ reports ahead of Hundred auction

-

Latest News6 days ago

Latest News6 days agoTariffs ruling is major blow to Trump’s second-term agenda