Opinion

Sri Lanka’s economic turmoil and value of Senanka Bibile drug policy

By Dr. Ajith Kumara

Consultant Physician

President, All Ceylon Medical Officers Association

Prof. Senaka Bibile is the greatest medical benefactor of humanity that Sri Lanka has hitherto produced. As a student, he was an all-rounder; he excelled in in academic and extracurricular activities including sports and art. He completed his First, Second and Final M.B. Examinations, all with First Class Honours and won the coveted Djunjishaw Dadabhoy Gold Medal in Medicine and the Rockwood Gold Medal in Surgery at the finals.

Both his talent and Marxist ideology motivated him to dedicate the rest of his life to a mission to develop the medical education and also introduce a national drug policy which was overwhelmingly grabbed by many nations and organisations across the world.

Background for National Drug Policy

The capitalist system is full of flaws due to the nature of commodity production. After the world war II, there was a transient progression which was soon followed by economic recessions across the world interpreted as great depression, OPEC oil crisis, Secondary banking crisis of 1973–1975 in the UK, Latin American debt crisis and so on.

Sri Lanka also witnessed a steady deterioration of balance payment from 1960s and economic growth rate progressively declined from 4.6%which was during 1950 and 1960 to 2.6% by 1974. From 1965 to 1970, the foreign exchange allocation for drugs was cut from a total of Rs. 33 million (Rs. 20 million for private and Rs. 13 million for Civil Medical Stores’ imports) to Rs. 24 million (Rp. 14 million and Rs. 10 million, respectively). Those drastic cut downs of health expenses irrespective of growth of population and steadily rise of drug prices resulted in significant drop in per capita pharmaceutical supply compromising health care across the country. Therefore, the prime minister requested Prof Senaka Bibile to cut down expenses without compromising patient care.

By 1970, Sri Lanka had no national health or drug policy like most other countries and drugs were imported for the government sector and for the private sector separately by the civil medical stores and 134 local agents of foreign suppliers respectively. Both the government and the private sector were heavily influenced by propaganda of the transnational companies (TNC).

Major recommendations in National Drug Policy

List of essential drugs

Prof. Senaka Bibile pioneered the publication of the Ceylon Hospitals Formulary from 1957 to identify essential drugs for the hospitals and introduced the concept of List of Essential Medicines in 1958 in Sri Lanka; it was new to the world and later taken up by WHO and other countries to ensure continuous supply of essential drugs at the lower possible cost.

Prof. Senaka Bibile pioneered the publication of the Ceylon Hospitals Formulary from 1957 to identify essential drugs for the hospitals and introduced the concept of List of Essential Medicines in 1958 in Sri Lanka; it was new to the world and later taken up by WHO and other countries to ensure continuous supply of essential drugs at the lower possible cost.

When preparing the drug list, many imitative drugs, which made no contribution to the therapeutic effect of a particular drug that were chosen on the basis of economy, large number of fixed combination drugs and drugs without clear therapeutic value or with high toxicity were left out. Drugs that have got a very slight structural difference to already known drugs, but with the same therapeutic effect (me-too drugs) were also deleted. So, he managed to minimise the drug list from about 4000 preparations to a reasonable number (about 600) without detrimental effect on patient care.

Centralisation of the purchase

The next major recommendation was the centralisation of purchase of both finished drugs according to the rationalised list and pharmaceutical chemicals for local manufacturers. State Pharmaceutical Cooperation (SPC) initiated this task of wholesale import of all drugs and pharmaceutical raw materials and, the purchase of locally processed pharmaceuticals. By the end of 1973, it could take over all imports.

Shopping around the world and accepting low price-bid as bulks rather than finished products helped save a lot of money. To maintain the quality of drugs, the pharmaceutical company should produce certificate of quality plus an independent certificate of quality from a reliable laboratory, an agent or an official body before accepting their bid.

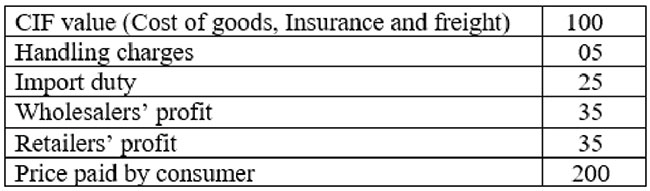

He suggested the following formula to understand the price of a drug to scientifically reduce its price. (See table)

CIF value ( Cost of goods, Insurance and freight) 100Handling charges 05Import duty 25Wholesalers profit 35Retailers profit 35Price to the consumer 200

Prof. Bibile pointed out that the wholesale import of raw materials and bulk pharmaceuticals at the most favourable price (at a lowest possible CIF value) will enable drug to be obtained and sold at the lowest price rather than fighting to limit wholesalers and retailers profit.

Ignore the patent law

The other recommendation was to abolish the patent law. Until that time, Sri Lanka had not been able to purchase patent products from any other manufacturer even though the drug was manufactured in a different process. Therefore, Sri Lanka could not buy cheaper products manufactured by a process different to those used by the original patent holders. Hence, it was suggested to amend the patent law so that only process patents would apply but not the product patents similar to the manner of operating the patent law in many countries such as Japan, Sweden, Denmark, Switzerland and most of the socialist countries.

Drug distribution and advertising

Repacking of bulk imported drugs and distribution of the drugs to the government sector and also to the private sector should be done by the state trading cooperation.

Drug advertising and education of doctors about drugs via brochures from pharmaceutical firms and their representatives should cease and local manufactures too should let the cooperation to advertise on their drugs.

Nomenclature

The report strongly recommended using generic names of medications instead of their trade names in prescriptions.

The report strongly recommended using generic names of medications instead of their trade names in prescriptions.

State Pharmaceutical Industry

Manufacturing pharmaceuticals in the country should also be started under the guidelines set by the government according to the essential drug list using the materials imported by the state, leaving the promotion and distribution to the state. If any manufacturer proved recalcitrant, the government has the authority to nationalise them. With this recommendation, by 1973, Sri Lanka m,anufacuired 47 essential drugs and, by 1974, and it increased to 71 drugs while saving more than 450,000 USD for the country.

Quality control of drugs

It was suggested to establish a quality control laboratory with a trained staff. Initially, he suggested getting consultants for the laboratory and to train staff through the WHO until local counterparts can take over the function.

Pharmacies, Pharmacists and their training

This was one of the most neglected aspect in health system by then. He rec eived assistance from Dr. J. Chilton of the University of Glasgow and a WHO consultant in Pharmacoloy, in training of pharmacists and to recommend the setting up of model pharmacies in the Colombo hospitals. The pharmacology course was later upgraded to a two year university diploma course according to his proposals.

In addition to these, the report has addressed about the research, monitoring and continuous development of human resources and infrastructure too.

Therefore, when analysing the Bibile Policy, it is clear that it is not merely an attempt to control the prices of drugs but, a very comprehensive national strategy for pharmaceutical sector in the health system.

National Drug policy to the world

Prof. Bibile was given the opportunity to present his novel model of pharmaceutical policy at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development in 1976 and it was soon supported by World Health Organization (WHO) and other United Nations agencies as it would give enormous benefit to the third world countries.

By the year 2,000, over 100 countries had national pharmaceutical policies and 88 countries had introduced the essential drug concept to medical and pharmacy curricula. In 1971, both Chile and Sri Lanka started centralised bulk procurement but, Chile failed due to the power of pharmaceutical companies and the lack of strong political will at their end.

In the early 1980s, Bangladesh ranked as the world’s second poorest country with the average per capita income of US$130. However, they succeeded in national pharmacological policy due to strong political commitment giving a good example to the world that if the vital ingredient of political will and commitment are there, the real progress is possible irrespective of the power of the pharmaceutical giants.

Sri Lankans failure

Signs of failure appeared from the outset of the policy implementation in Sri Lanka. In the report in 1976 written by Prof. Bibile and Dr. Sanjaya Lal, it is clearly mentioned that the government was neither monolithic nor fully consistent with its strategy and, after 1975; government changed its economic strategy and hindered the policy implementation.

By now, Sri Lanka has faced a severe economic crisis with a shortage of foreign currency and an inability to provide basic requirements such as food, education and health of the citizens. Hospitals have run out of drugs including life-saving medications and surgical items.

Nevertheless, there are numerous combinations of various types of vitamins; plenty of medications which have no proven benefits, me-too drug and many counterfeit medications in the market wasting our foreign currency! About 30% of health expenditure is spent for pharmaceuticals.

If Sri Lanka had implemented Bibile drug policy and imported drugs according to an essential medicine list, heath budget could have efficiently be utilised to buy them while avoiding wasting of foreign currency for unnecessary medications. That would be an expeditious solution to the current crisis in essential medicines. As planned earlier, if the pharmaceutical manufacturing industry is commenced, it will be an excellent way of earning the much needed foreign currency in the long term. Therefore, the implementation of Bibile drug policy is much more important today than ever as a comprehensive approach to the crisis in health system to ensure the availability of essential medications.

Opinion

Sovereignty without Governance is a hollow shield

Globalisation exposes weakness and failed governance; and invites intervention – A message to all inept governments everywhere

The government of Burkina Faso has shattered the illusion of party politics, dissolving every political party in the nation. Its justification is blunt: parties divide the people, fracture sovereignty, and allow corrupt elites to hijack the sacred powers that belong to the citizenry.

This is not an aberration. It is the recurring disease of fragile states. Haiti, Somalia, Sudan, Venezuela, Sri Lanka—their governments collapse under the weight of incompetence, leaving their people abandoned and their sovereignty hollow. These failed states do not merely fail themselves; they burden the world. Their chaos spills across borders, draining the strength of nations that still stand.

Globalisation does not forgive weakness. It exposes it. And as global opinion hardens, a new world order is taking shape—one that no longer tolerates decay. The moment of rupture came when US President Donald Trump seized Nicolás Maduro from his Venezuelan hideout and dragged him to face justice in America.

Predictably, the chorus of populists cried “oil!” They shouted about imperialism while ignoring the rot of Maduro’s failed government and his collapse in legitimacy. But the truth is unavoidable: if Venezuela had been competently governed, Trump would never have had the opening to topple its leadership. Weakness invited conquest. Failure opened the door.

Singapore offers the perfect counterexample. It is perhaps the best-governed nation on earth, and for that reason it is untouchable. Strong governance is the only true shield of sovereignty. Without it, sovereignty is a brittle shell, a flag waving over ruins.

Trump’s precedent will echo across continents. China, Russia, India—regional powers are watching, calculating, preparing. The message is unmistakable: Sovereignty is conditional. It is not guaranteed by history or by law. It is guaranteed only by strength, by competence, by the will to govern effectively.

This is the revolutionary truth: nations that fail to govern themselves will be governed by others. The age of excuses is over. The age of accountability has begun. Weak governments will fall. Strong governments will endure. And the people, sovereign and indivisible, will demand leaders who can protect their destiny—or see them replaced by those who can.

By Brigadier (Rtd) Ranjan de Silva

rpcdesilva@gmail.com

Opinion

CORRECTION

In the article, “Let My Country Awake…” published yesterday, it was erroneously said that Sri Lanka was celebrating 77 years of Independence. It should be corrected as 78 years of Independence. The error is regretted.

Opinion

“Let My Country Awake …”

Where the mind is without fear, and the head is held high;

Where knowledge is free;

Where the world has not been broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls;

Where words come out from the depth of truth;

Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards perfection;

Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way into the dreary desert sand of dead habit;

Where the mind is led forward by thee into ever-widening thought and action

Into that heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake.

– Rabindranath Tagore, Gitanjali, 35

As Sri Lanka marks seventy-seven years of independence, this moment demands more than flags, ceremonies, or familiar slogans. It demands memory, honesty, and moral courage. Once spoken of with affection and hope as Mother Lanka, the nation today increasingly resembles a wounded child—carried again and again across fragile hanging bridges, suspended between survival and collapse. This image is not new to our cultural consciousness. Long before today’s crises, Sri Lankans encountered it through literature and radio, most memorably in Henry Jayasena’s Hunuwataye Kathawa (1967), the Sinhala radio drama adaptation of Bertolt Brecht’s The Caucasian Chalk Circle, written during World War II (WWII), broadcast by Radio Ceylon and later staged across the island. Heard in village homes and city neighborhoods, the story quietly shaped a moral imagination we now seem to have forgotten.

In Hunuwataye Kathawa, a child is placed at the center of a chalk circle, claimed by two women. One is Natella, the biological mother who abandons the child during a moment of danger and later returns—not out of love, but driven by entitlement, inheritance, and power. The other is Grusha, a poor servant who risks everything to protect the child, feeding her, carrying her across perilous terrain, and choosing care over comfort. When ordered by the judge to pull the child out of the circle, Grusha refuses. She would rather let go than injure the child. Justice, the story teaches, belongs not to those who claim ownership most loudly, but to those who practice responsibility and restraint. For generations of Sri Lankans, this lesson entered the heart not through policy or economics, but through art.

Beneath Sri Lanka’s recurring failures lies a deeper wound: collective forgetfulness. It is indeed incredible how a nation colonised by foreign powers for over four centuries, battered by people’s insurrections and national struggles ever since, divided by a 30-year-long ethnic war, shaken by a Tsunami, inflamed by Easter Bombings 2019, hit by Covid-19 shutdown, and bankrupt by economic crisis, just to mention a few before the devastating Cyclone Ditwah that rocked the entire nation not many weeks ago, could be so forgetful of its tragedies. This insight was articulated with striking clarity by Dr. Arvind Subramanian, the former Chief Economic Advisor to the Government of India, speaking at an event organised by The Examiner in Colombo on Jan 21, 2026. Subramanian observed the nation’s troubling tendency to forget its own history—its tragedies, hard-earned lessons, and warnings—and to embrace uncritically whatever is new in a pattern-line manner. This historical amnesia traps Sri Lanka in vicious cycles of debt, dependency, and unscientific thinking. When memory fails, every crisis feels unprecedented; when learning fails, every mistake is repeated.

Consequently, after seventy-eight years of independence from the last colonial rule, Sri Lanka still stands inside that chalk circle. Mother Lanka, once admired for free education, public health, and social mobility, has over the decades been reduced to a wounded child carried across unstable political, economic, and environmental bridges. Different governments, armed with different ideologies and promises, have taken turns holding her. Some carried her carefully; others dropped her midway; still others claimed her loudly while burdening her with unsustainable debt, weakened institutions, superstitious demeanors, and short-term fixes that mortgaged the future. This mother-made-child nation was perpetually oscillating between collapse and recovery. Yet instead of healing her wounds, with every passing Independence Day, we repeatedly celebrated and argued over who owned her.

This long post-independence journey reveals two recurring patterns. There have been many Natella-like approaches—entitlement without responsibility, nationalism without sacrifice, populism without prudence. These abandon the child in moments of crisis, only to return when power, contracts, or prestige are at stake. Alongside them, however, there have also been Grusha-like moments—imperfect, painful, often unpopular, yet rooted in reform, discipline, and care. These moments prioritise institutions over personalities, education over spectacle, sustainability over extraction, science over superstitions, and responsibility over applause. They are the moments that keep the child alive. The thorough cleaning that the whole nation recently experienced with Cyclone Ditwah also reminds us, among many other lessons, about the power and the need of these Grusha-like moments. It reminds us that the real celebration of freedom requires not slogans but breaking free from Natella-like approaches and, after the immersion that she just experienced, that it is only possible in and through at least three kinds of voluntary and ongoing immersions (3P Immersions)—disciplines that reshape not only policy but also personal and national character—Immersion of Poverty, Immersion of Plurality, and Immersion of Prudence.

The immersion of poverty, both spiritual and material, is deeply rooted in Buddhist teaching of tanhaā and āśā—the restless craving for more than one truly needs or can sustain. It is that which enables us to be constantly mindful of ourselves, not only who we really were, who we actually are, and what we continue to become, but also what we are really in need of. Nationally speaking, it involves acknowledging the country’s geopolitical placement, the strengths of its proud history and civilisation, and the limitations of its repeated struggles and political dismay. While material realism, when faced honestly, disciplines excess and teaches gratitude for what we already have, the immersion in poverty should remind us about how greed can lead to corruption and about the illusion that fulfillment lies in accumulation. A nation that does not discern its desires with its own resources and real capacity—human, historical, cultural, and environmental—will always mortgage its future to satisfy temporary cravings. We must ask ourselves honestly: how different are we today from the colonial era, when our decisions were shaped by external powers, if we remain bound by foreign debts, external models, and a forgetting of our own identity?

The immersion of plurality should not be understood as a slogan, but as a lived ethic. Sri Lanka’s diversity of language, religion, culture, geography, and memory is not the problem; it is the unfinished promise. Sinhala and Tamil, Muslim and Burgher, Buddhist, Hindu, Christian, and Muslim, village and city, coast and hill—all belong to the child in the chalk circle. While Natella-like politics weaponise difference and division, pulling the child apart to claim possession, Grusha-like care holds plurality together, recognising that it is the unity in diversity that sustains, protects, and frees the child, carrying it safely home. Freedom figures like Siddi Lebbe, Veera Puran Appu, Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan, Sir Ponnambalam Arunachalam, C. W. W. Kannangara, T. B. Jayah, Anagarika Dharmapala, and D. S. Senanayake emerged from different faiths, languages, and regions, yet shared a common ethic: the country mattered more than self, party, or community. They were not perfect, but they were Grusha-like—unwilling to pull the child apart to prove ownership, willing instead to carry her patiently across danger.

Grusha-like care, therefore, holds plurality together, recognizing that no single group can carry the country alone. Rather, it is plurality which is the ground of freedom from coercion, selective justice, and hostage-taking—whether by professions, ideologies, or institutions that prioritize self-interest over the common good. It also demands freedom from resistance to positive change, especially when that resistance is motivated by private gain rather than the common welfare. A plural society asks: Does this serve the nation, or merely my group, my party, my advantage?

The immersion in prudence is perhaps the rarest and most neglected virtue. Prudence calls us to move from myth to science, from avidyā to vidyā, from superstition to evidence. Recent floods and landslides were not merely natural disasters; they were moral warnings. Thy painfully revealed what happens when desire overrides restraint, when planning ignores science, when land is abused, when short-term gain overrides long-term responsibility, and when development forgets sustainability. Freedom from disaster is inseparable from freedom from ignorance. Prudence teaches us to listen actively, speak intentionally, plan with evidence, build with environmental awareness, and govern with foresight. Prudence is not only about grand reforms; it is also very much about our everyday civic behaviour, such as how we treat Mother Earth and shared spaces.

For example, freedom from spitting on the ground, freedom from littering public places, and freedom from leaving behind what we refuse to clean or return. These are not small matters; they are indicators of whether people see the nation as a common home or as a place to be used and discarded. These are only a handful of many instances where we need to hear what JFK (John F. Kennedy) asked the Americans in 1961: “Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country”. The WWII-devastated Japan’s development is not built merely on technology, but on discipline, as systems like 5S cultivate order, responsibility, and respect for shared space. Clean Sri Lanka and the proposed Education Reforms 2026 can become transformative moments—but only if truth replaces pretense, cooperation replaces cynicism, and ownership replaces vengeful rhetoric. Prudence allows a nation to appreciate its ownness—its history, institutions, cultural resources, and the agendas for the common good—without rejecting learning from the world. Without prudence, novelty becomes addiction, and reform becomes fashion.

Before the history repeats itself for another 77 years, either as a series of tragedy or comedy, it is important, therefore, to recognise that freedom from debt, disaster, and dependency (national or personal) is impossible without all three types of immersions working together—poverty of desire, plurality of belonging, and prudence of action. Initiatives such as education reform and Clean Sri Lanka offer genuine opportunities, but only if we cooperate, think long-term, and resist turning reform into another slogan. This raises an uncomfortable question: Do we truly want to be free? Or are we content to remain in the same rut, so long as ignorance is preserved, education is left unreformed, and distractions are supplied by a handful of greedy politicians—their vengeful rhetoric, their allies, lopsided media, and mushrooming content creators—while the powerful continue to benefit from it all? Freedom is demanding. It asks for memory, restraint, cooperation, and courage. Dependency, by contrast, is easy.

Therefore, the question before us is not who shouts the loudest, who claims patriotism most aggressively, or who promises instant miracles. It is who remembers, who renounces, who embraces plurality, and who acts with prudence as her stewards and not owners. When are we going to immerse ourselves in these three immersions and be free? After Rabindranath Tagore’s poem, W. D. Amaradeva once sang, “Patu adahasnam paurinen lokaya kabaliwalata nobedi, jnanaya iwahal we… Ehew nidahase swarga rajyataṭ, mage dæśaya avadi karanu mena, Piyanani…“— Where knowledge keeps the world from being divided by the walls of narrow thoughts… Into that heaven of freedom, Father, let my country awake. How many poems, how many Amaradevas, how many freedom speeches, how many religious sermons, how many inundations, and how many struggles must come and go before we awaken to that truth and let Mother Lanka be out of that vicious pattern or circle of collapse and recovery—whole, healed, and free?

By Dr. Rashmi M. Fernando, S.J.

Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Rashmi.Fernando@lmu.edu | https://orcid.org/0009-0006-3310-721X

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoSri Lanka, the Stars,and statesmen

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoHayleys Mobility ushering in a new era of premium sustainable mobility

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoSLIM-Kantar People’s Awards 2026 to recognise Sri Lanka’s most trusted brands and personalities

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoAdvice Lab unveils new 13,000+ sqft office, marking major expansion in financial services BPO to Australia

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoArpico NextGen Mattress gains recognition for innovation

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoAltair issues over 100+ title deeds post ownership change

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoSri Lanka opens first country pavilion at London exhibition

-

Editorial5 days ago

Editorial5 days agoGovt. provoking TUs