Midweek Review

Sri Lanka: Quest for Justice, Rule of Law and Democratic Rights

By Shamindra Ferdinando

With an eye on the 46th session of the Geneva-based United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) later this month, the highly influential Global Tamil Forum (GTF), Centre for Human Rights and Global Justice, New York University, Sri Lanka Campaign for Peace and Justice and The Canadian Tamil Congress have brought in ‘big guns’ for a combined onslaught on Sri Lanka this week.

Among the participants, at a two-hour webinar, titled ‘Sri Lanka: Quest for Justice, Rule of Law and Democratic Rights’, scheduled for Friday, Feb. 12 (UK 1:30 pm; Europe/South Africa 3.30 pm; India/Sri Lanka 7:00 pm IST; Canada/US 8:30 am; Australia 12.30 am) are former UN Assistant Secretary General, Charles Petrie, former Special Rapporteur on the promotion of truth, justice, reparation and guarantee of non-recurrence, Pablo de Greiff and former US Ambassador-at-Large for Global Criminal Justice, Stephen J. Rapp.

The panelists includes Tamil National Alliance (TNA) lawmaker M.A. Sumanthiran, PC, former Commissioner of HRCSL Ambika Satkunanathan, Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA) representative Attorney-at-Law Bhavani Fonseka, civil society activist. Shreen Saroor, and Sri Lanka Muslim Congress (SLMC) representative, Attorney-at-Law, Ameer Faaiz. Melissa Dring, of the Sri Lanka Campaign for Peace and Justice, is the moderator.

Their project has received a tremendous boost with the US returning to the Geneva body. The US quit UNHRC in June 2018.

The TNA, in late 2001, recognized the LTTE as the sole representative of the Tamil community. The LTTE held that privileged status in the eyes of the TNA, until Sri Lanka brought the war to a successful conclusion, in May 2009. The TNA is a direct beneficiary of the LTTE’s demise. Of course, Sumanthiran cannot be entirely held responsible for TNA’s actions as he joined the one-time LTTE mouthpiece, as a National List MP, in April 2010.

Why back Fonseka?

Sumanthiran entered Parliament a couple of months after the TNA wholeheartedly backed war-winning Army Commander Gen. Sarath Fonseka’s presidential candidature. Perhaps, Sumanthiran should explain on Feb 12, as to why the TNA, having accused the Army, Fonseka led with such efficiency, till the crushing of the formidable Tigers militarily, of genocide and then backed him to the hilt at the presidential poll that came soon afterwards. The TNA cannot conveniently ignore the fact that all Northern and Eastern electoral districts overwhelmingly voted for Fonseka though he lost the overall contest by a staggering 1.8 mn votes. Why did Tamils vote for Fonseka after accusing him, and his men, of genocide after they crushed the LTTE, which many pundits repeatedly claimed the Lankan security forces were incapable of achieving?

Participation of Petrie, Pablo de Greiff and Rapp, in Friday’s webinar, is of extreme importance. Petrie headed an ‘Internal Review Panel on UN actions in Sri Lanka’ that dealt with the final phase of the conflict, in his capacity as Special Rapporteur; De Greiff visited Sri Lanka on four occasions, between 2015 and 2019, and Rapp visited Colombo twice, in 2012 and 2014.

The Petrie report conveniently forgot how India formed half a dozen armed groups in the ‘80s to terrorize Sri Lanka, just to teach the then JRJ a lesson for being overtly pro-West and perhaps for derogatively comparing Mrs. Bandaranaike and her son, Anura with Mrs Gandhi and her son Sanjay. The Indian intervention was meant to pave the way for the deployment of her Army in the Northern and Eastern regions. The Indian project went awry. India ended up losing nearly 1,500 officers, and men, here, in less than three years. In addition, double that number received injuries. The military mission was aborted in March 1990. A year later, the LTTE assassinated Rajiv Gandhi, who, in his capacity as the Indian Prime Minister authorized the deployment of the Indian Army here. Can India ever absolve herself of the crime of causing massive chaos and destruction to this country as a result of her diabolical project here? The Petrie report also ignored how the LTTE scuttled the last bid to negotiate a settlement by quitting peace talks in April 2003. The LTTE’s abrupt move jeopardized the survival of UNP leader Ranil Wickremesinghe’s government and paved the way for its ouster in the following year.

Those who really value justice, rule of law, as well as democratic rights, should examine the Indian intervention here, too. Petrie and de Greiff should use the opportunity to explain the UN’s failure in the ‘80s to thwart the murderous Indian project. The UN played along in a devious plot to destabilise Sri Lanka, over the years. The UN’s response to the LTTE, during the Vanni offensive is no exception. The issue is whether the use of ‘human shields’, by the LTTE, could have been averted if the UN took tangible measures against the LTTE, especially in the wake of its detention of Tamil UN employees, accused of helping civilians to flee the Vanni west.

Did Petrie probe abductions of

UN workers?

Did Petrie inquire into the abductions after the revelation of secret UN powwow with the LTTE, led to the UN confirmation of the incident at daily UN media briefings, in New York, by the Secretary General’s Spokesperson Montas (The Island expose of UN employees abducted by LTTE: UN HQ admits Colombo Office kept it in the dark – The Island, April 28, 2007) Beginning April 20, 2007 (LTTE detains UN workers). The Island published several news items on the issue. The TNA, or those who issued media statements at the drop of a hat, remained conveniently silent. The TNA’s decision to remain quiet is understandable due to its close working relationship with the LTTE. Many an eyebrow was raised when the European Union election monitors openly accused the Tigers of helping the TNA to win 22 seats in the North and East, in 2004, by stuffing ballot boxes on its behalf. In the following year, the TNA, on behalf of the LTTE, ordered Northern Tamils to boycott the November presidential election. CPA’s Executive Director, Dr. Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu, is the only civil society leader to criticize the LTTE-TNA move.

The LTTE and the TNA set the stage for an all-out war. The LTTE commenced claymore attacks, in early Dec 2005. In January 2006, the LTTE blasted a Navy Fast Attack Craft (FAC) off Trincomalee; in late, April 2006 they made an abortive bid to assassinate Fonseka, and in early Oct 2006 an attempt was made on Defence Secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s life. The LTTE lost the Eastern Province, eight months later.

The TNA, as well as some sections of the international community remained strongly confident of the LTTE’s military superiority, until it was evicted from Kilinochchi. The LTTE lost Kilinochchi in early January, less than two weeks after Canada-based veteran political and defence analyst D.B.S. Jeyaraj asserted that the LTTE was on the verge of reversing territorial gains made by the Army. The rest is history.

None of those who are harping today about the loss of civilian life bothered to publicly appeal to the LTTE to let go of its human shields. The TNA certainly owed an explanation why it remained silent over the LTTE taking cover behind the civilian population. Against the backdrop of the UN mollycoddling the LTTE, Prabhakaran forced Tamil civilians to follow the retreating LTTE fighting cadre from the western part of the Vanni region across the Kandy-Jaffna A9 road towards the Mullaitivu coast.

Oslo’s missive to Basil

The then Norwegian Ambassador, Tore Hattrem, acknowledged the rapidly developing crisis in the eastern part of the Vanni region, in a letter to Presidential Advisor, Basil Rajapaksa, as the Army stepped-up operations. Hattrem’s missive to Rajapaksa revealed their serious concerns over Prabhakaran’s refusal to give up human shields. The Island, some time ago, published the hitherto unknown Norwegian note, headlined ‘Offer/Proposal to the LTTE’, and personally signed by Ambassador Hattrem. The Norwegian envoy was writing to Basil Rajapaksa on behalf of those countries trying to negotiate a ceasefire between the government and the LTTE, to facilitate the release of civilians, held hostage by the latter.

The following is the text of Ambassador Hattrem’s letter, dated Feb. 16, 2009, addressed to Basil Rajapaksa: “I refer to our telephone conversation today. The proposal to the LTTE on how to release the civilian population, now trapped in the LTTE controlled area, has been transmitted to the LTTE through several channels. So far, there has been, regrettably, no response from the LTTE and it doesn’t seem to be likely that the LTTE will agree with this in the near future.“

How many civilians perished during the Vanni offensive? The UN Secretary General’s Panel of Experts (PoE) report, released on March 31, 2011, having faulted the Army, on three major counts, alleged the massacre of at least 40,000 civilians. Let me reproduce the relevant paragraph, bearing no 137, verbatim: “In the limited surveys that have been carried out in the aftermath of the conflict, the percentage of people reporting dead relatives is high. A number of credible sources have estimated that there could have been as many as 40,000 civilian deaths. Two years after the end of the war, there is no reliable figure for civilian deaths, but multiple sources of information indicate that a range of up to 40,000 civilian deaths cannot be ruled out at this stage. Only a proper investigation can lead to the identification of all of the victims and to the formulation of an accurate figure for the total number of civilian deaths.”

The PoE arrived at the figure on the basis of information provided by persons whose identities would remain confidential till 2031 (20 years since the release of POE report in March 2011). The UN has strangely guaranteed confidentiality of ‘sources’ even after the lapse of the mandatory 20-year period. Perhaps, Petrie and Pablo de Greiff should explain how the UN pushed ahead with subsequent actions against Sri Lanka, based purely on still unverified accusations made by ghost accusers. In other words, Sri Lanka was convicted by the PoE report after a kangaroo court trial. How convenient?

Having failed to obtain the anticipated response to its public call for submissions, the PoE had no option but to extend the deadline to Dec 31, 2010. The PoE posted a notice in English on the UN website on Oct 27, 2010 calling for submissions on or before Dec 15, 2010. Sinhala and Tamil versions of the notice too, were subsequently posted. The PoE received 4,000 submissions from 2,300 persons. None of them were verified at any stage of the Geneva process, leading to yet bizarre Sri Lanka co-sponsoring of the Geneva Resolution on Oct 1, 2015 against itself.

When the writer raised the issue with the UN, as well as the then UNDP Resident Representative in Colombo, Subinay Nandy, whether the UN would do away with the confidentiality clause to facilitate the UNHRC probe, the Colombo mission issued the following statement after having consulted UN headquarters. The UN said: “The High Commissioner for Human Rights will now be making arrangements for a comprehensive investigation requested by the UNHRC and the issue of the confidentiality clause will need to be considered at a later stage,” (UN to revive 20-year confidentiality clause ‘at a later stage’- The Island April 7, 2014). The UN never did. Sri Lanka never exploited the matter.

The US, the British, as well as the EU, too, in spite of their push for an international war crimes probe, recently ruled out the possibility of them calling for a review of the confidentiality clause (EU, too, won’t call for review of 20-year UN confidentiality clause – The Island April 9, 2014).

Successive governments, and even those interested in defending the country, never really bothered to examine undisputed facts that were in Sri Lanka’s favour. The incumbent administration is no exception to this type of inexcusable lapses at great cost to the country.

PoE contradicts own claims

Interestingly, the PoE report contradicted its own claim of 40,000 killings. Unlike the unsubstantiated claim of 40,000 deaths, the paragraph bearing No 134 dealt with the issue on the basis of reliable sources acceptable to the UN.

It would be pertinent to reproduce the relevant section verbatim: “The United Nations Country Team is one source of information; in a document that was never released publicly, it estimated a total figure of 7,721 killed and 18,479 injured from August 2008 up to 13 May 2009, after which it became too difficult to count. In early February 2009, the United Nations started a process of compiling casualty figures, although efforts were hindered by lack of access. An internal ‘Crisis Operating Group’ was formed to collect reliable information regarding civilian casualties and other humanitarian concerns. In order to calculate a total casualty figure, the group took figures from RDHS as the baseline, using reports from national staff of the United Nations and NGOs, inside the Vanni, the ICRC, religious authorities and other sources to cross-check and verify the baseline. The methodology was quite conservative: if an incident could not be verified by these sources or could have been double counted, it was dismissed. Figures emanating from sources that could be perceived as biased, such as Tamil Net, were dismissed, as were Government sources outside the Vanni.”

Amnesty International (AI) in Sept. 2011, launched its own report, titled: ‘When will they get justice? Failures of Sri Lanka’s Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission.’ The report estimated the number of civilian deaths, due to military action, as over 10,000. AI based its assertion on eyewitness testimony and information from aid workers.

AI, too, guaranteed confidentiality of its ‘sources.’ Perhaps for want of close cooperation among those who had wanted to drag Sri Lanka before an international tribunal, they contradicted themselves in respect of the primary charge. Interestingly, none of those, except British Labour Party MP Siobhan McDonagh (Mitcham and Morden-Labour) propagating lies, regarding civilian deaths, dared to blatantly lie in Parliament about losses suffered by the LTTE. McDonagh estimated the number of LTTE cadres killed, in fighting, from January 1, 2009, to May 19, 2009, at 60,000. Successive governments didn’t even bother to raise the Labour MP’s lie with the UK though The Island pointed out the need to clarify matters. The absurd claim was made during the third week of Sept 2011, in Parliament. Sri Lanka never realized the need to inquire into the possibility of British parliamentarians’ relationship with the Tamil Diaspora. In fact, some politicians had benefited from their relationship. The GTF hired former MP for Enfield, North Joan Ryan, as its policy advisor. Of course, the GTF had the backing of all major political parties, with key politicians participating in its inauguration in the UK Parliament, in Feb 2010, in the wake of the LTTE’s demise.

Let us hope Friday’s webinar responds to Lord Naseby disclosure pertaining to loss of lives, based on confidential cables from British High Commission in Colombo (January-May 2009) and US Defence Advisor Lt. Col. Lawrence Smith’s declaration in June 2011 (two months after the release of the PoE report). Both contradicted the position taken by British and the US. Sri Lanka never made a genuine effort to build-up a proper defence in Geneva. Sri Lanka shirked high profile opportunities to exploit startling revelations made by Wikileaks. The British are yet to release all confidential cables that dealt with the Vanni offensive, though Lord Naseby managed to secure some, following legal intervention made by him. That took over two years as the UK tried to withhold information which could have helped the UNHRC to ascertain the truth and Sri Lanka being absolved of these totally exaggerated accusations by interested parties against her.

A cable from Geneva

A cable, dated July 15, 2009, signed by the then Geneva-based US Ambassador Clint Williamson cleared the Army of crimes against humanity during the Vanni offensive. The cable, addressed to the US State Department, had been based on a confidential conversation between Ambassador Williamson and the then ICRC head of operations for South Asia, Jacque de Maio, on July 9, 2009. Ambassador Williamson wrote: “The Army was determined not to let the LTTE escape from its shrinking territory, even though this meant the civilians being kept hostage by the LTTE were at an increasing risk. So, de Maio said, while one could safely say that there were ‘serious, widespread violations of international humanitarian law,’ by the Sri Lankan forces, it didn’t amount to genocide. He could cite examples of where the Army had stopped shelling when the ICRC informed them it was killing civilians. In fact, the Army actually could have won the military battle faster, with higher civilian casualties, yet they chose a slower approach which led to a greater number of Sri Lankan military deaths. He concluded, however, by asserting that the GoSL recognized its obligation to protect civilians, despite the approach leading to higher military casualties.”

The Army lost 2,400 personnel during the January-May 2009 period. The losses were the worst suffered by the Army during the Eelam War IV (Aug 2006-May 2009). Frontline fighting formations lost a further 70 personnel, who were categorized as missing in action, in 2009. Deaths due to reasons other than combat during the same period were placed at 334. Thousands were injured. The losses suffered on the Vanni east front, during the first five months of 2009, was over 100 per cent, when compared with battlefield losses in the previous year. For the whole of 2008, the Army lost 2,174 killed and 43 missing in action.

Army Chief General Shavendra Silva told the writer that the Sri Lankan military had the wherewithal to decimate the LTTE in a far shorter period, if not for the human shields. “We paid a heavy price for being mindful of the civilian presence among the LTTE cadres. Restricted use of long range weapons, as well as air support on the Vanni east front, caused quite a bit of problems.”

The US slapped a travel ban on General Silva, in Feb 2020, over his role as the GoC of the celebrated 58 Division (which started as Task Force 1). The US move is an affront to the war-winning armed forces, who achieved their arduous task against all odds and the political leadership that backed them to the hilt, irrespective of threats to try them, too, for war crimes. Unfortunately, even the utterly unsubstantiated action against Gen. Shavendra Silva hadn’t jolted the government, as well as those genuinely interested in defending the country, to re-examine the accountability issue.

Sri Lanka’s pathetic and continuing failure has allowed Western powers to use the LTTE rump and Tamil Diaspora in a high profile project to overwhelm the country.

Midweek Review

At the edge of a world war

In September 1939, as Europe descended once more into catastrophe, E. H. Carr published The Twenty Years’ Crisis. Twenty years had separated the two great wars—twenty years to reflect, to reconstruct, to restrain. Yet reflection proved fragile. Carr wrote with unsentimental clarity: once the enemy is crushed, the “thereafter” rarely arrives. The illusion that power can come first and morality will follow is as dangerous as the belief that morality alone can command power. Between those illusions, nations lose themselves.

His warning hovers over the present war in Iran.

The “thereafter” has long haunted American interventions—after Afghanistan, after Iraq, after Libya. The enemy can be dismantled with precision; the aftermath resists precision. Iran is not a small theater. It is a civilization-state with a geography three times larger than Iraq. At its southern edge lies the Strait of Hormuz, narrow in width yet immense in consequence. Geography does not argue; it compels.

Long before Carr, in the quiet anxiety of the eighteenth century, James Madison, principal architect of the Constitution, warned that war was the “true nurse of executive aggrandizement.” War concentrates authority in the name of urgency. Madison insisted that the power to declare war must rest with Congress, not the president—so that deliberation might restrain impulse. Republics persuade themselves that emergency powers are temporary. History rarely agrees.

Then, at 2:30 a.m., the abstraction becomes decision.

Donald Trump declares war on Iran. The announcement crosses continents before markets open in Asia. Within twenty-four hours, Ali Khamenei, who ruled for thirty-seven years, is killed. The President calls him one of history’s most evil figures and presents his death as an opening for the Iranian people.

In exile, Reza Pahlavi hails the moment as liberation. In less than forty-eight hours, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps collapses under overwhelming air power. A regime that endured decades falls swiftly. Military efficiency appears absolute. Yet efficiency does not resolve legitimacy.

The joint strike with Israel is framed as necessary and pre-emptive. Retaliation follows across the Gulf. The architecture of energy trade becomes fragile. Shipping routes are recalculated. Markets respond before diplomacy finds its language.

It is measured in the price of petrol in Colombo. In the bus fare in Karachi. In the rising cost of cooking gas in Dhaka. It is heard in the anxious voice of a migrant worker in Doha calling home to Kandy, asking whether contracts will be renewed, whether flights will continue, whether wages will be delayed. It is calculated in foreign reserves already strained, in currencies that tremble at rumor, in budgets forced to choose between subsidy and solvency.

Zaara was the breadwinner of her house in Sri Lanka. Her husband had been unemployed for years. At last, he secured an opportunity to travel to Israel as a foreign worker—like many Sri Lankans who depend on employment in the Middle East. It was to be their turning point: a small house repaired, debts reduced, dignity restored.

Now she lowers her eyes when she speaks. For Zaara, geopolitics is not theory. It is fear measured in distance—between a construction site abroad and a village waiting at home.

The war in Iran has shattered calculations that once felt practical. Nations like Sri Lanka now require strategic foresight to navigate unfolding realities. Reactive responses—whether to natural disasters or external shocks like this conflict—can cripple economies far faster than gradual pressures. Disruptions to energy imports, migrant remittances, and foreign reserves show how distant wars ripple into daily lives.

War among great powers is debated in think tanks. Its consequences are lived in markets—and in quiet kitchens where uncertainty sits heavier than hunger.

The conflict does not unfold in isolation. It enters the strategic calculus of China and Russia, both attentive to precedent. Power projected beyond the Western hemisphere reshapes perceptions in the Eastern theater. Iran’s transformation intersects directly with broader alignments. In 2021, Beijing and Tehran signed a twenty-five-year strategic agreement. By 2025, China was purchasing the majority of Iran’s exported oil at discounted rates. Energy underwrote strategy. That continuity has been disrupted. Yet strategic relationships do not vanish; they adjust.

In Winds of Change, my new book, I reproduce Nicholas Spykman’s 1944 two-theater confrontation map—Europe and the Pacific during the Second World War. Spykman distinguished maritime power from amphibian projection. Control of the Rimland determined balance. Then, the United States fought across two vast theaters. Today, Europe remains unsettled through Ukraine, the Pacific simmers over Taiwan and the South China Sea, Latin America remains sensitive, and the Middle East has been abruptly transformed. The architecture of multi-theater tension reappears.

At this juncture, the reflections of Marwan Bishara acquire weight. America’s ultimate power, he argues, resides in deterrence, not in the habitual use of force. Power, especially when shared, stabilizes. Force, when used with disregard for international law, breeds instability and humiliation. Arrogance creates enemies and narrows judgment. It is no surprise that many Americans themselves believe the United States should not act alone.

America’s strength does not rest solely in its military reach. Its economy constitutes roughly one-third of global output and generates close to 40 percent of the world’s research and development. Structural power—economic, technological, institutional—has historically underwritten deterrence. When force becomes the primary instrument, influence risks becoming coercion.

The United States now confronts simultaneous pressures across continents. The Second World War demonstrated the capacity to sustain multi-theater engagement; the post-9/11 wars revealed the exhaustion that follows prolonged intervention. Iran, larger and geopolitically deeper, presents a scale that cannot be resolved by air power alone.

Carr’s “thereafter” waits patiently. Military victory may be swift; political reconstruction is slow. Bishara reminds us that deterrence sustains stability, while force risks unraveling it.

At the edge of a potential world war, the decisive question is not who strikes first, but who restrains longest.

History watches. And in places far from the battlefield, mothers wait for phone calls that may not come.

Asanga Abeyagoonasekera is a Senior Research Fellow at the Millennium Project, Washington, D.C., and the author of Winds of Change: Geopolitics at the Crossroads of South and Southeast Asia, published by World Scientific

Midweek Review

Live Coals Burst Aflame

Live coals of decades-long hate,

Are bursting into all-consuming flames,

In lands where ‘Black Gold’ is abundant,

And it’s a matter to be thought about,

If humans anywhere would be safe now,

Unless these enmities dying hard,

With roots in imperialist exploits,

And identity-based, tribal violence,

Are set aside and laid finally to rest,

By an enthronement of the principle,

Of the Equal Dignity of Humans.

By Lynn Ockersz

Midweek Review

Saga of the arrest of retired intelligence chief

Retired Maj. Gen. Suresh Sallay’s recent arrest attracted internatiattention. His long-expected arrest took place ahead of the seventh anniversary of the bombings. Multiple blasts claimed the lives of nearly 280 people, including 45 foreigners. State-owned international news television network, based in Paris, France 24, declared that arrest was made on the basis of information provided by a whistleblower. The French channel was referring to Hanzeer Azad Moulana, who earlier sought political asylum in the West and one-time close associate of State Minister Sivanesathurai Chandrakanthan aka Pilleyan. May be the fiction he wove against Pilleyan and others may have been to strengthen his asylum claim there. Moulana is on record as having told the British Channel 4 that Sallay allowed the attack to proceed with the intention of influencing the 2019 presidential election. The French news agency quoted an investigating officer as having said: “He was arrested for conspiracy and aiding and abetting the Easter Sunday attacks. He has been in touch with people involved in the attacks, even recently.”

****

Suresh Sallay of the Directorate of Military Intelligence (DMI) received the wrath of Yahapalana Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, in 2016, over the reportage of what the media called the Chavakachcheri explosives detection made on March 30, 2016. Premier Wickremesinghe found fault with Sallay for the coverage, particularly in The Island. Police arrested ex-LTTE child combatant Edward Julian, alias Ramesh, after the detection of one suicide jacket, four claymore mines, three parcels containing about 12 kilos of explosives, to battery packs and several rounds of 9mm ammunition, from his house, situated at Vallakulam Pillaiyar Kovil Street. Chavakachcheri police made the detection, thanks to information provided by the second wife of Ramesh. Investigations revealed that the deadly cache had been brought by Ramesh from Mannar (Detection of LTTE suicide jacket, mines jolts government: Fleeing Tiger apprehended at checkpoint, The Island, March 31, 2016).

The then Jaffna Security Forces Commander, Maj. Gen. Mahesh Senanayake, told the writer that a thorough inquiry was required to ascertain the apprehended LTTE cadre’s intention. The Chavakachcheri detection received the DMI’s attention. The country’s premier intelligence organisation meticulously dealt with the issue against the backdrop of an alleged aborted bid to revive the LTTE in April 2014. Of those who had been involved in the fresh terror project, three were killed in the Nedunkerny jungles. There hadn’t been any other incidents since the Nedunkerny skirmish, until the Chavakachcheri detection.

Piqued by the media coverage of the Chavakachcheri detection, the Sirisena-Wickremesinghe administration tried to silence the genuine Opposition. As the SLFP had, contrary to the expectations of those who voted for the party at the August 2015 parliamentary elections, formed a treacherous coalition with the UNP, the Joint Opposition (JO) spearheaded the parliamentary opposition.

The Criminal Investigation Department (CID) questioned former External Affairs Minister and top JO spokesman, Prof. G.L. Peiris, over a statement made by him regarding the Chavakachcheri detection. The former law professor questioned the legality of the CID’s move against the backdrop of police declining to furnish him a certified copy of the then acting IGP S.M. Wickremesinghe’s directive that he be summoned to record a statement as regards the Chavakachcheri lethal detection.

One-time LTTE propagandist Velayutham Dayanidhi, a.k.a. Daya Master, raised with President Maithripala Sirisena the spate of arrests made by law enforcement authorities, in the wake of the Chavakachcheri detection. Daya Master took advantage of a meeting called by Sirisena, on 28 April, 2016, at the President’s House, with the proprietors of media organisations and journalists, to raise the issue. The writer having been among the journalists present on that occasion, inquired from the ex-LETTer whom he represented there. Daya Master had been there on behalf of DAN TV, Tamil language satellite TV, based in Jaffna. Among those who had been detained was Subramaniam Sivakaran, at that time Youth Wing leader of the Illankai Thamil Arasu Kadchi (ITAK), the main constituent of the now defunct Tamil National Alliance. In addition to Sivakaran, the police apprehended several hardcore ex-LTTE cadres (LTTE revival bid confirmed: TNA youth leader arrested, The Island April 20, 2016).

Ranil hits out at media

Subsequent inquiries revealed the role played by Sivakaran in some of those wanted in connection with the Chavakachcheri detection taking refuge in India. When the writer sought an explanation from the then TNA lawmaker, M.A. Sumanthiran, regarding Sivakaran’s arrest, the lawyer disowned the Youth Wing leader. Sumanthiran emphasised that the party suspended Sivakumaran and Northern Provincial Council member Ananthi Sasitharan for publicly condemning the TNA’s decision to endorse Maithripala Sirisena’s candidature at the 2015 presidential election (Chava explosives: Key suspects flee to India, The Island, May 2, 2016).

Premier Wickremesinghe went ballistic on May 30, 2016. Addressing the 20th anniversary event of the Sri Lanka Muslim Media Forum, at the Sports Ministry auditorium, the UNP leader castigated the DMI. Alleging that the DMI had been pursuing an agenda meant to undermine the Yahapalana administration, Wickremesinghe, in order to make his bogus claim look genuine, repeatedly named the writer as part of that plot. Only Wickremesinghe knows the identity of the idiot who influenced him to make such unsubstantiated allegations. The top UNPer went on to allege that The Island, and its sister paper Divaina, were working overtime to bring back Dutugemunu, a reference to war-winning President Mahinda Rajapaksa. A few days later, sleuths from the Colombo Crime Detection Bureau (CCD) visited The Island editorial to question the writer where lengthy statements were recorded. The police were acting on the instructions of the then Premier, who earlier publicly threatened to send police to question the writer.

In response to police queries about Sallay passing information to the media regarding the Chavakachcheri detection and subsequent related articles, the writer pointed out that the reportage was based on response of the then ASP Ruwan Gunasekera, AAL and Sumanthiran, as had been reported.

Wickremesinghe alleged, at the Muslim media event, that a section of the media manipulated coverage of certain incidents, ahead of the May Day celebrations.

In early May 2016 Wickremesinghe disclosed that he received assurances from the police, and the DMI, that as the LTTE had been wiped out the group couldn’t stage a comeback. The declaration was made at the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute for International Relations and Strategic Studies (LKIIRIS) on 3 May 2016. Wickremesinghe said that he sought clarifications from the police and the DMI in the wake of the reportage of the Chavakachcheri detection and related developments (PM: LTTE threat no longer exists, The Island, May 5, 2016).

The LTTE couldn’t stage a comeback as a result of measures taken by the then government. It would be a grave mistake, on our part, to believe that the eradication of the LTTE’s conventional military capacity automatically influenced them to give up arms. The successful rehabilitation project, that had been undertaken by the Rajapaksa government and continued by successive governments, ensured that those who once took up arms weren’t interested in returning to the same deadly path.

In spite of the TNA and others shedding crocodile tears for the defeated Tigers, while making a desperate effort to mobilise public opinion against the government, the public never wanted the violence to return. Some interested parties propagated the lie that regardless of the crushing defeat suffered in the hands of the military, the LTTE could resume guerilla-type operations, paving the way for a new conflict. But by the end of 2014, and in the run-up to the presidential election in January following year, the situation seemed under control, especially with Western countries not wanting to upset things here with a pliant administration in the immediate horizon. Soon after the presidential election, the government targeted the armed forces. Remember Sumanthiran’s declaration that the ITAK Youth Wing leader Sivakaran had been opposed to the TNA backing Sirisena at the presidential poll.

The US-led accountability resolution had been co-sponsored by the Sirisena-Wickremesinghe duo to appease the TNA and Tamil Diaspora. The Oct. 01, 2016, resolution delivered a knockout blow to the war-winning armed forces. The UNP pursued an agenda severely inimical to national interests. It would be pertinent to mention that those who now represent the main Opposition, Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB), were part of the treacherous UNP.

Suresh moved to Malaysia

The Yahapalana leadership resented Sallay’s work. They wanted him out of the country at a time a new threat was emerging. The government attacked the then Justice Minister Dr. Wijeyadasa Rajapakshe, PC, who warned of the emerging threat from foreign-manipulated local Islamic fanatics on 11 Nov. 2016, in Parliament. Rajapakshe didn’t mince his words when he underscored the threat posed by some Sri Lanka Muslim families taking refuge in Syria where ISIS was running the show. The then government, of which he was part o,f ridiculed their own Justice Minister. Both Sirisena and Wickremesinghe feared action against extremism may cause erosion of Muslim support. By then Sallay, who had been investigating the deadly plot, was out of the country. The Yahapalana government believed that the best way to deal with Sallay was to grant him a diplomatic posting. Sally ended up in Malaysia, a country where the DMI played a significant role in the repatriation of Kumaran Pathmanathan, alias KP, after his arrest there.

The Yahapalana leadership resented Sallay’s work. They wanted him out of the country at a time a new threat was emerging. The government attacked the then Justice Minister Dr. Wijeyadasa Rajapakshe, PC, who warned of the emerging threat from foreign-manipulated local Islamic fanatics on 11 Nov. 2016, in Parliament. Rajapakshe didn’t mince his words when he underscored the threat posed by some Sri Lanka Muslim families taking refuge in Syria where ISIS was running the show. The then government, of which he was part o,f ridiculed their own Justice Minister. Both Sirisena and Wickremesinghe feared action against extremism may cause erosion of Muslim support. By then Sallay, who had been investigating the deadly plot, was out of the country. The Yahapalana government believed that the best way to deal with Sallay was to grant him a diplomatic posting. Sally ended up in Malaysia, a country where the DMI played a significant role in the repatriation of Kumaran Pathmanathan, alias KP, after his arrest there.

Having served the military for over three cadres, Sallay retired in 2024 in the rank of Major General. Against the backdrop of his recent arrest, in connection with the ongoing investigation into the 2019 Easter Sunday carnage, The Island felt the need to examine the circumstances Sallay ended up in Malaysia at the time. Now, remanded in terms of the Prevention of terrorism Act (PTA), he is being accused of directing the Easter Sunday operation from Malaysia.

Pivithuru Hela Urumaya leader and former Minister Udaya Gammanpila has alleged that Sallay was apprehended in a bid to divert attention away from the deepening coal scam. Having campaigned on an anti-corruption platformm in the run up to the previous presidential election, in September 2024, the Parliament election, in November of the same year, and local government polls last year, the incumbent dispensation is struggling to cope up with massive corruption issues, particularly the coal scam, which has not only implicated the Energy Minister but the entire Cabinet of Ministers as well.

The crux of the matter is whether Sallay actually met would-be suicide bombers, in February 2018, in an estate, in the Puttalam district, as alleged by the UK’s Channel 4 television, like the BBC is, quite famous for doing hatchet jobs for the West. This is the primary issue at hand. Did Sallay clandestinely leave Malaysia to meet suicide bombers in the presence of Hanzeer Azad Moulana, one-time close associate of State Minister Sivanesathurai Chandrakanthan, aka Pilleyan, former LTTE member?

The British channel raised this issue with Sallay, in 2023, at the time he served as Director, State Intelligence (SIS). Sallay is on record as having told Channel 4 Television that he was not in Sri Lanka the whole of 2018 as he was in Malaysia serving in the Sri Lankan Embassy there as Minister Counsellor.

Therefore, the accusation that he met several members of the National Thowheeth Jamaath (NTJ), including Mohamed Hashim Mohamed Zahran, in Karadipuval, Puttalam, in Feb. 2018, was baseless, he has said.

The intelligence officer has asked the British television station to verify his claim with the Malaysian authorities.

Responding to another query, Sallay had told Channel 4 that on April 21, 2019, the day of the Easter Sunday blasts, he was in India, where he was accommodated at the National Defence College (NDC). That could be verified with the Indian authorities, Sallay has said, strongly denying Channel 4’s claim that he contacted one of Pilleyan’s cadres, over, the phone and directed him to pick a person outside Hotel Taj Samudra.

According to Sallay, during his entire assignment in Malaysia, from Dec. 2016 to Dec. 2018, he had been to Colombo only once, for one week, in Dec. 2017, to assist in an official inquiry.

Having returned to Colombo, Sallay had left for NDC, in late Dec. 2018, and returned only after the conclusion of the course, in November 2019.

Sallay has said so in response to questions posed by Ben de Pear, founder, Basement Films, tasked with producing a film for Channel 4 on the Easter Sunday bombings.

The producer has offered Sallay an opportunity to address the issues in terms of Broadcasting Code while inquiring into fresh evidence regarding the officer’s alleged involvement in the Easter Sunday conspiracy.

The producer sought Sallay’s response, in August 2023, in the wake of political upheaval following the ouster of Gotabaya Rajapaksa, elected at the November 2019 presidential election.

At the time, the Yahapalana government granted a diplomatic appointment to Sallay, he had been head of the Directorate of Military Intelligence (DMI). After the 2019 presidential election, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa named him the Head of SIS.

The Basement Films has posed several questions to Sallay on the basis of accusations made by Hanzeer Azad Moulana.

In response to the film producer’s query regarding Sallay’s alleged secret meeting with six NTJ cadres who blasted themselves a year later, Sallay has questioned the very basis of the so called new evidence as he was not even in the country during the period the clandestine meeting is alleged to have taken place.

Contradictory stands

Following Sajith Premadasa’s anticipated defeat at the 2019 presidential election, Harin Fernando accused the Catholic Church of facilitating Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s victory. Fernando, who is also on record as having disclosed that his father knew of the impending Easter Sunday attacks, pointed finger at the Archbishop of Colombo, Rt. Rev Malcolm Cardinal Ranjith, for ensuring Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s victory.

Former President Maithripala Sirisena, as well as JVP frontliner Dr. Nalinda Jayathissa, accused India of masterminding the Easter Sunday bombings. Then there were claims of Sara Jasmin, wife of Katuwapitiya suicide bomber Mohammed Hastun, being an Indian agent who was secretly removed after the Army assaulted extremists’ hideout at Sainthamaruthu in the East. What really had happened to Sara Jasmin who, some believe, is key to the Easter Sunday puzzle.

Then there was huge controversy over the arrest of Attorney-at-Law Hejaaz Hizbullah over his alleged links with the Easter Sunday bombers. Hizbullah, who had been arrested in April 2020, served as lawyer to the extremely wealthy spice trader Mohamed Yusuf Ibrahim’s family that had been deeply involved in the Easter Sunday plot. Mohamed Yusuf Ibrahim had been on the JVP’s National List at the 2015 parliamentary elections. The lawyer received bail after two years. Two of the spice trader’s sons launched suicide attacks, whereas his daughter-in-law triggered a suicide blast when police raided their Dematagoda mansion, several hours after the Easter Sunday blasts.

Investigations also revealed that the suicide vests had been assembled at a factory owned by the family and the project was funded by them. It would be pertinent to mention that President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s government never really bothered to conduct a comprehensive investigation to identify the Easter Sunday terror project. Perhaps, their biggest failure had been to act on the Presidential Commission of Inquiry (PCoI) recommendations. Instead, President Rajapaksa appointed a six-member committee, headed by his elder brother, Chamal Rajapaksa, to examine the recommendations, probably in a foolish attempt to improve estranged relations with the influential Muslim community. That move caused irreparable damage and influenced the Church to initiate a campaign against the government. The Catholic Church played quite a significant role in the India- and US-backed 2022 Aragalaya that forced President Rajapaksa to flee the country.

Interested parties exploited the deterioration of the national economy, leading to unprecedented declaration of the bankruptcy of the country in April 2022, to mobilie public anger that was used to achieve political change.

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoBrilliant Navy officer no more

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoSri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCabinet nod for the removal of Cess tax imposed on imported good

-

Features4 days ago

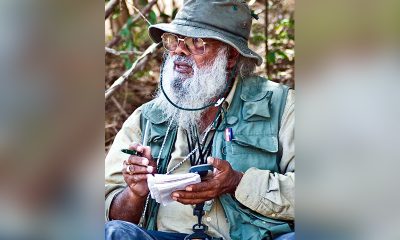

Features4 days agoA life in colour and song: Rajika Gamage’s new bird guide captures Sri Lanka’s avian soul

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoOverseas visits to drum up foreign assistance for Sri Lanka

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoSri Lanka to Host First-Ever World Congress on Snakes in Landmark Scientific Milestone

-

Latest News2 days ago

Latest News2 days agoAround 140 people missing after Iranian navy ship sinks off coast of Sri Lanka

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoWar in Middle East sends shockwaves through Sri Lanka’s export sector