Features

Some reflections on sinhala popular music

By Uditha Devapriya

In Modernizing Composition: Sinhala Song, Poetry, and Politics in Twentieth-Century Sri Lanka (University of California Press, 2017), Garrett Field emphasises the role that radio played in disseminating and elevating musical standards in the newly independent colonies of South Asia. The 1950s, when this process played itself out, was a period in which the state and institutional politics “became inextricable from linguistic nationalism.” Across Sri Lanka, these links found their fullest expression in Radio Ceylon, specifically after the latter began to employ professional Sinhala songwriters.

This was not a development unique to Sri Lanka. As Coonoor Kripalani has argued, in India radio served a pivotal function “in building patriotism and nationhood” after independence. Radio was cheaper and more accessible, while in Sri Lanka it predated television by three decades. In India, as in Sri Lanka, it provided litterateurs, composers, and performers who had depended on the patronage of the colonial bourgeoisie, and had thrived on the cultural revivalist movements of the 19th century, a more solid institutional footing.

Field’s book is important for several reasons, in particular its attempt at understanding the subtleties of Sinhala music through translation. However, it ends at a point – the mid-1960s – when Sinhala music was about to embark on its most colourful period.

To say this is not to belittle Field’s book. Modernizing Composition fills a great many gaps, including its exploration of the links between commercial capitalism and the revival of Sinhala music in the early 20th century. It also acknowledges that music and poetry cannot be viewed in isolation from one another, particularly in the context of newly decolonised societies searching for a cultural identity. Indeed, its immense scope and breadth are why Field’s analysis, sound as it is, should be carried forward to the 1960s and 1970s, especially since it was in these later periods that the factors that underpinned the popularity of Sinhala music – free education and linguistic nationalism – reached their apogees.

To be sure, these two periods – the 1940s-1950s and the 1960s-1970s – were qualitatively different. They imbibed different cultural influences and pandered to different audiences and markets. Following Sheldon Pollock, Professor Field uses the theory of “cosmopolitan vernacularism” to explain how, following independence, poets and songwriters grafted or superimposed classical literary aesthetics on regional languages and thereby gave birth to “new premodern vernacular literatures.” Throughout South Asia in general, and across Sri Lanka in particular, it was Sanskrit that indigenous poets and songwriters turned to in their quest to elevate their linguistic heritages and lineages. The more Westernised among them also sought inspiration from modernist American and European poetry.

Since I am by no means a specialist in anthropology, I cannot pass judgments on how these developments played themselves out in the 1960s. Yet it is clear that these developments had their origins in the period immediately preceding 1956. Now, 1956 meant a great many things to a great many people. To some it symbolised the triumph of the indigenous over the foreign; to others, the triumph of ethno-religious majoritarianism. Whichever way you look at it, 1956 provided the crucible through Sinhala music could continue to transform, to evolve, and to thrive. Here I am concerned with two musical forms: baila and pop music. My justification for this is simple: it is these two genres which facilitated the popularisation, or what I call the “middle-browing”, of Sinhala music after the 1960s.

Baila is more controversial and more contentious than Sinhala pop. As Anne Sheeran has noted, baila as a musical genre, activates both conformist and conservative elements. It at once provokes many of us to flout tradition, and compels not a few others to protest that flouting of tradition. Thus nationalist ideologues can bemoan the deterioration of cultural values, and parents can bemoan their children’s addition to the latest cultural trends, by invoking its name. In other words, is it the proverbial bogeyman in the room, a scapegoat for the death of culture, and the last resort of the puritan.

It is all these things. Yet as one historian communicated to me some years ago, baila stands with ves natum as one of the most uniquely indigenous cultural forms in Sri Lanka, an irony given their foreign roots (Portuguese and Indian). And in the 1960s and 1970s, it underwent a transition that would define the trajectory of Sinhala music.

The significance of this transition cannot be overrated. Such transitions were taking place in other cultural spheres as well. In literature, the renaissance that had been heralded by Martin Wickramasinghe had meandered to the popular fiction of Karunasena Jayalath. In film, Lester James Peries’s experiments had enabled a number of directors, including two of his assistants and colleagues, Titus Thotawatte (Chandiya) and Tissa Liyanasuriya (Saravita), to seek a middle-ground between artistic and commercial cinema. The situation was rather different in the theatre, where a new generation of bilingual writers, including Dayananda Gunawardena, Premaranjith Tilakaratne, G. D. L. Perera, Henry Jayasena, Dhamma Jagoda, Gunasena Galappatti, and Simon Navagattegama, continued to hold on to some semblance of a benchmark. Yet even they sought a break from the past.

By this I do not mean to say, or suggest, that there was a complete rupture in Sinhala music. The old musical forms continued to thrive, if not evolve. The first generation of lyricists and songwriters, including Chandraratne Manawasinghe, Madawala Rathnayake, and the great Mahagama Sekara, continued to write for old collaborators, as well as new voices. However, many of them remained utterly classical in their views on music, and it was these views that prevailed at Radio Ceylon. As Tissa Abeysekera has controversially remarked, on more than one occasion, this had the effect of stunting the growth of Western music in Sri Lanka, even as Western music was gaining popularity over the airwaves and on film in India. Against that backdrop, a new generation of composers was bound to emerge.

In a series of essays, all anthologised in Roots, Reflections and Reminiscences (Sarasavi, 2007), Abeysekera argues that the conflict here was between those who advocated the Indianisation or Sanskritisation of local music and those who promoted more vernacular, indigenous musical forms. He refers to the visit of S. N. Ratanjankar and the audition that was conducted at Radio Ceylon, under his supervision, and points out that these led to the stagnation of Sinhala music. However, Garrett Field’s take on the visit, and the audition, is different: citing a speech that he delivered at the Royal Asiatic Society in Colombo, a speech Abeysekara does not quote from, Field contends that Ratanjankar wanted artistes to “create a modern song, based on folk poetry and folk music.” This is at variance with Abeysekera’s reading of events, which make it out that Ratanjankar, if not the authorities at Radio Ceylon, marginalised proponents of folk music, including Sunil Shantha.

I think both Field and Abeysekera have a point, and both are correct. While promoting if not advocating the indigenisation of music, Sinhala composers consciously went back to North Indian influences. Contrary to what Abeysekera has written, what this achieved in the end was a fusion of disparate cultural elements – Sinhala folk poetry and Sanskrit aesthetics – which laid the groundwork for an efflorescence in Sinhala music. At the same time, those who diverged from the mainstream trend of incorporating North Indian musical elements retreated to a world of their own. They included not just Sunil Shantha, but also the first-generation proponents of baila, like Wally Bastiansz, who found a niche audience eager to listen to them but failed to penetrate more middle-class audiences.

The question thus soon arose as to who could push these developments on to mainstream listeners. In the 1950s Sinhala composers and lyricists had popularised folk poetry through sarala gee, or light classical songs. In the 1960s baila had succeeded folk poetry as a popular musical form. The task of making baila palatable for young, Sinhala speaking audiences, fell on a new generation of composers. This new generation found their inspiration not so much in North Indian music as in Elvis, the Beatles, and Jimi Hendrix.

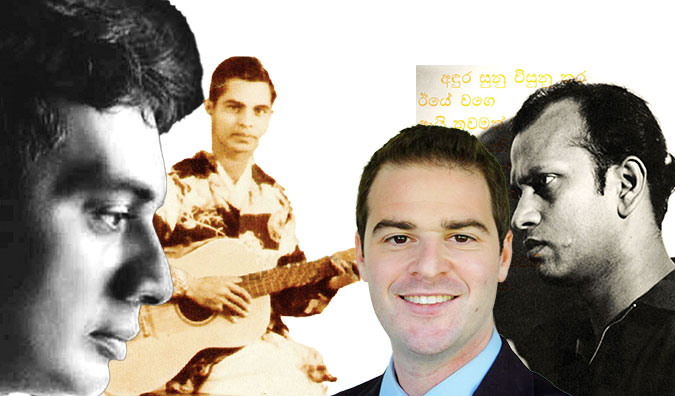

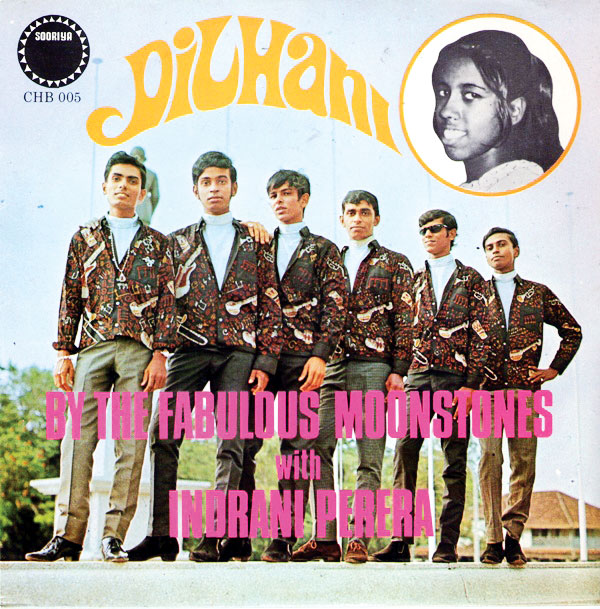

Their turning point, if it can be called that, came in 1967, a decade after 1956, when a little-known group, called The Moonstones, made their debut on Radio Ceylon. Featuring guitars, congas, maracas, and Cuban drums, their impact was immediate, so much so that within the next two years, both Phillips and Sooriya had signed them onboard.

What The Moonstones, and its lead Clarence Wijewardena, did was not so much challenge or flout the musical establishment of their time as to perform for an audience different in outlook and attitude to the audiences which the establishment had pandered to until then. This is a very important point, since I do not think there was a grand overarching conflict, in any way, between the new generation and the old. The old lyricists continued to write for their collaborators, and they willingly collaborated with the new voices: Sekara, for instance, wrote a song for one of the more prominent new voices, Indrani Perera, while Amaradeva sang for Clarence Wijewardena. Contrary to Abeysekera, I hence prefer to see this period as one of collaboration rather than outright, fight-to-the-death competition.

Field’s analysis, as I mentioned at the beginning of this essay, ends somewhere in the 1960s. His research is impeccably sound, and it deserves being carried forward. More than anything else, we need to know more about the audiences that the new composers, vocalists, and lyricists pandered to, and how exactly the latter groups pandered to them. We also need to know how their predecessors, who remained active in this period, interacted with them. I am specifically concerned here with the period from 1967 – when The Moonstones entered the mainstream – to 1978 – when a new government, a new economy, and an entirely new set of cultural forms and influences took the lead. All this represents much fieldwork for the anthropologist and historian of Sri Lankan, and South Asian, music. But it is the least we can do, given Garrett Field’s wonderful book and the many gaps it fills.

(The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com.)

Features

Freedom for giants: What Udawalawe really tells about human–elephant conflict

If elephants are truly to be given “freedom” in Udawalawe, the solution is not simply to open gates or redraw park boundaries. The map itself tells the real story — a story of shrinking habitats, broken corridors, and more than a decade of silent but relentless ecological destruction.

“Look at Udawalawe today and compare it with satellite maps from ten years ago,” says Sameera Weerathunga, one of Sri Lanka’s most consistent and vocal elephant conservation activists. “You don’t need complicated science. You can literally see what we have done to them.”

What we commonly describe as the human–elephant conflict (HEC) is, in reality, a land-use conflict driven by development policies that ignore ecological realities. Elephants are not invading villages; villages, farms, highways and megaprojects have steadily invaded elephant landscapes.

Udawalawe: From Landscape to Island

Udawalawe National Park was once part of a vast ecological network connecting the southern dry zone to the central highlands and eastern forests. Elephants moved freely between Udawalawe, Lunugamvehera, Bundala, Gal Oya and even parts of the Walawe river basin, following seasonal water and food availability.

Today, Udawalawe appears on the map as a shrinking green island surrounded by human settlements, monoculture plantations, reservoirs, electric fences and asphalt.

“For elephants, Udawalawe is like a prison surrounded by invisible walls,” Sameera explains. “We expect animals that evolved to roam hundreds of square nationakilometres to survive inside a box created by humans.”

Elephants are ecosystem engineers. They shape forests by dispersing seeds, opening pathways, and regulating vegetation. Their survival depends on movement — not containment. But in Udawalawa, movement is precisely what has been taken away.

Over the past decade, ancient elephant corridors have been blocked or erased by:

Irrigation and agricultural expansion

Tourism resorts and safari infrastructure

New roads, highways and power lines

Human settlements inside former forest reserves

“The destruction didn’t happen overnight,” Sameera says. “It happened project by project, fence by fence, without anyone looking at the cumulative impact.”

The Illusion of Protection

Sri Lanka prides itself on its protected area network. Yet most national parks function as ecological islands rather than connected systems.

“We think declaring land as a ‘national park’ is enough,” Sameera argues. “But protection without connectivity is just slow extinction.”

Udawalawe currently holds far more elephants than it can sustainably support. The result is habitat degradation inside the park, increased competition for resources, and escalating conflict along the boundaries.

“When elephants cannot move naturally, they turn to crops, tanks and villages,” Sameera says. “And then we blame the elephant for being a problem.”

The Other Side of the Map: Wanni and Hambantota

Sameera often points to the irony visible on the very same map. While elephants are squeezed into overcrowded parks in the south, large landscapes remain in the Wanni, parts of Hambantota and the eastern dry zone where elephant density is naturally lower and ecological space still exists.

“We keep talking about Udawalawe as if it’s the only place elephants exist,” he says. “But the real question is why we are not restoring and reconnecting landscapes elsewhere.”

The Hambantota MER (Managed Elephant Reserve), for instance, was originally designed as a landscape-level solution. The idea was not to trap elephants inside fences, but to manage land use so that people and elephants could coexist through zoning, seasonal access, and corridor protection.

“But what happened?” Sameera asks. “Instead of managing land, we managed elephants. We translocated them, fenced them, chased them, tranquilised them. And the conflict only got worse.”

The Failure of Translocation

For decades, Sri Lanka relied heavily on elephant translocation as a conflict management tool. Hundreds of elephants were captured from conflict zones and released into national parks like Udawalawa, Yala and Wilpattu.

The logic was simple: remove the elephant, remove the problem.

The reality was tragic.

“Most translocated elephants try to return home,” Sameera explains. “They walk hundreds of kilometres, crossing highways, railway lines and villages. Many die from exhaustion, accidents or gunshots. Others become even more aggressive.”

Scientific studies now confirm what conservationists warned from the beginning: translocation increases stress, mortality, and conflict. Displaced elephants often lose social structures, familiar landscapes, and access to traditional water sources.

“You cannot solve a spatial problem with a transport solution,” Sameera says bluntly.

In many cases, the same elephant is captured and moved multiple times — a process that only deepens trauma and behavioural change.

Freedom Is Not About Removing Fences

The popular slogan “give elephants freedom” has become emotionally powerful but scientifically misleading. Elephants do not need symbolic freedom; they need functional landscapes.

Real solutions lie in:

Restoring elephant corridors

Preventing development in key migratory routes

Creating buffer zones with elephant-friendly crops

Community-based land-use planning

Landscape-level conservation instead of park-based thinking

“We must stop treating national parks like wildlife prisons and villages like war zones,” Sameera insists. “The real battlefield is land policy.”

Electric fences, for instance, are often promoted as a solution. But fences merely shift conflict from one village to another.

“A fence does not create peace,” Sameera says. “It just moves the problem down the line.”

A Crisis Created by Humans

Sri Lanka loses more than 400 elephants and nearly 100 humans every year due to HEC — one of the highest rates globally.

Yet Sameera refuses to call it a wildlife problem.

“This is a human-created crisis,” he says. “Elephants are only responding to what we’ve done to their world.”

From expressways cutting through forests to solar farms replacing scrublands, development continues without ecological memory or long-term planning.

“We plan five-year political cycles,” Sameera notes. “Elephants plan in centuries.”

The tragedy is not just ecological. It is moral.

“We are destroying a species that is central to our culture, religion, tourism and identity,” Sameera says. “And then we act surprised when they fight back.”

The Question We Avoid Asking

If Udawalawe is overcrowded, if Yala is saturated, if Wilpattu is bursting — then the real question is not where to put elephants.

The real question is: Where have we left space for wildness in Sri Lanka?

Sameera believes the future lies not in more fences or more parks, but in reimagining land itself.

“Conservation cannot survive as an island inside a development ocean,” he says. “Either we redesign Sri Lanka to include elephants, or one day we’ll only see them in logos, statues and children’s books.”

And the map will show nothing but empty green patches — places where giants once walked, and humans chose. roads instead.

By Ifham Nizam

Features

Challenges faced by the media in South Asia in fostering regionalism

SAARC or the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation has been declared ‘dead’ by some sections in South Asia and the idea seems to be catching on. Over the years the evidence seems to have been building that this is so, but a matter that requires thorough probing is whether the media in South Asia, given the vital part it could play in fostering regional amity, has had a role too in bringing about SAARC’s apparent demise.

SAARC or the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation has been declared ‘dead’ by some sections in South Asia and the idea seems to be catching on. Over the years the evidence seems to have been building that this is so, but a matter that requires thorough probing is whether the media in South Asia, given the vital part it could play in fostering regional amity, has had a role too in bringing about SAARC’s apparent demise.

That South Asian governments have had a hand in the ‘SAARC debacle’ is plain to see. For example, it is beyond doubt that the India-Pakistan rivalry has invariably got in the way, particularly over the past 15 years or thereabouts, of the Indian and Pakistani governments sitting at the negotiating table and in a spirit of reconciliation resolving the vexatious issues growing out of the SAARC exercise. The inaction had a paralyzing effect on the organization.

Unfortunately the rest of South Asian governments too have not seen it to be in the collective interest of the region to explore ways of jump-starting the SAARC process and sustaining it. That is, a lack of statesmanship on the part of the SAARC Eight is clearly in evidence. Narrow national interests have been allowed to hijack and derail the cooperative process that ought to be at the heart of the SAARC initiative.

However, a dimension that has hitherto gone comparatively unaddressed is the largely negative role sections of the media in the SAARC region could play in debilitating regional cooperation and amity. We had some thought-provoking ‘takes’ on this question recently from Roman Gautam, the editor of ‘Himal Southasian’.

Gautam was delivering the third of talks on February 2nd in the RCSS Strategic Dialogue Series under the aegis of the Regional Centre for Strategic Studies, Colombo, at the latter’s conference hall. The forum was ably presided over by RCSS Executive Director and Ambassador (Retd.) Ravinatha Aryasinha who, among other things, ensured lively participation on the part of the attendees at the Q&A which followed the main presentation. The talk was titled, ‘Where does the media stand in connecting (or dividing) Southasia?’.

Gautam singled out those sections of the Indian media that are tamely subservient to Indian governments, including those that are professedly independent, for the glaring lack of, among other things, regionalism or collective amity within South Asia. These sections of the media, it was pointed out, pander easily to the narratives framed by the Indian centre on developments in the region and fall easy prey, as it were, to the nationalist forces that are supportive of the latter. Consequently, divisive forces within the region receive a boost which is hugely detrimental to regional cooperation.

Two cases in point, Gautam pointed out, were the recent political upheavals in Nepal and Bangladesh. In each of these cases stray opinions favorable to India voiced by a few participants in the relevant protests were clung on to by sections of the Indian media covering these trouble spots. In the case of Nepal, to consider one example, a young protester’s single comment to the effect that Nepal too needed a firm leader like Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was seized upon by the Indian media and fed to audiences at home in a sensational, exaggerated fashion. No effort was made by the Indian media to canvass more opinions on this matter or to extensively research the issue.

In the case of Bangladesh, widely held rumours that the Hindus in the country were being hunted and killed, pogrom fashion, and that the crisis was all about this was propagated by the relevant sections of the Indian media. This was a clear pandering to religious extremist sentiment in India. Once again, essentially hearsay stories were given prominence with hardly any effort at understanding what the crisis was really all about. There is no doubt that anti-Muslim sentiment in India would have been further fueled.

Gautam was of the view that, in the main, it is fear of victimization of the relevant sections of the media by the Indian centre and anxiety over financial reprisals and like punitive measures by the latter that prompted the media to frame their narratives in these terms. It is important to keep in mind these ‘structures’ within which the Indian media works, we were told. The issue in other words, is a question of the media completely subjugating themselves to the ruling powers.

Basically, the need for financial survival on the part of the Indian media, it was pointed out, prompted it to subscribe to the prejudices and partialities of the Indian centre. A failure to abide by the official line could spell financial ruin for the media.

A principal question that occurred to this columnist was whether the ‘Indian media’ referred to by Gautam referred to the totality of the Indian media or whether he had in mind some divisive, chauvinistic and narrow-based elements within it. If the latter is the case it would not be fair to generalize one’s comments to cover the entirety of the Indian media. Nevertheless, it is a matter for further research.

However, an overall point made by the speaker that as a result of the above referred to negative media practices South Asian regionalism has suffered badly needs to be taken. Certainly, as matters stand currently, there is a very real information gap about South Asian realities among South Asian publics and harmful media practices account considerably for such ignorance which gets in the way of South Asian cooperation and amity.

Moreover, divisive, chauvinistic media are widespread and active in South Asia. Sri Lanka has a fair share of this species of media and the latter are not doing the country any good, leave alone the region. All in all, the democratic spirit has gone well into decline all over the region.

The above is a huge problem that needs to be managed reflectively by democratic rulers and their allied publics in South Asia and the region’s more enlightened media could play a constructive role in taking up this challenge. The latter need to take the initiative to come together and deliberate on the questions at hand. To succeed in such efforts they do not need the backing of governments. What is of paramount importance is the vision and grit to go the extra mile.

Features

When the Wetland spoke after dusk

By Ifham Nizam

As the sun softened over Colombo and the city’s familiar noise began to loosen its grip, the Beddagana Wetland Park prepared for its quieter hour — the hour when wetlands speak in their own language.

World Wetlands Day was marked a little early this year, but time felt irrelevant at Beddagana. Nature lovers, students, scientists and seekers gathered not for a ceremony, but for listening. Partnering with Park authorities, Dilmah Conservation opened the wetland as a living classroom, inviting more than a 100 participants to step gently into an ecosystem that survives — and protects — a capital city.

Wetlands, it became clear, are not places of stillness. They are places of conversation.

Beyond the surface

In daylight, Beddagana appears serene — open water stitched with reeds, dragonflies hovering above green mirrors.

Yet beneath the surface lies an intricate architecture of life. Wetlands are not defined by water alone, but by relationships: fungi breaking down matter, insects pollinating and feeding, amphibians calling across seasons, birds nesting and mammals moving quietly between shadows.

Participants learned this not through lectures alone, but through touch, sound and careful observation. Simple water testing kits revealed the chemistry of urban survival. Camera traps hinted at lives lived mostly unseen.

Demonstrations of mist netting and cage trapping unfolded with care, revealing how science approaches nature not as an intruder, but as a listener.

Again and again, the lesson returned: nothing here exists in isolation.

Learning to listen

Perhaps the most profound discovery of the day was sound.

Wetlands speak constantly, but human ears are rarely tuned to their frequency. Researchers guided participants through the wetland’s soundscape — teaching them to recognise the rhythms of frogs, the punctuation of insects, the layered calls of birds settling for night.

Then came the inaudible made audible. Bat detectors translated ultrasonic echolocation into sound, turning invisible flight into pulses and clicks. Faces lit up with surprise. The air, once assumed empty, was suddenly full.

It was a moment of humility — proof that much of nature’s story unfolds beyond human perception.

Sethil on camera trapping

The city’s quiet protectors

Environmental researcher Narmadha Dangampola offered an image that lingered long after her words ended. Wetlands, she said, are like kidneys.

“They filter, cleanse and regulate,” she explained. “They protect the body of the city.”

Her analogy felt especially fitting at Beddagana, where concrete edges meet wild water.

She shared a rare confirmation: the Collared Scops Owl, unseen here for eight years, has returned — a fragile signal that when habitats are protected, life remembers the way back.

Small lives, large meanings

Professor Shaminda Fernando turned attention to creatures rarely celebrated. Small mammals — shy, fast, easily overlooked — are among the wetland’s most honest messengers.

Using Sherman traps, he demonstrated how scientists read these animals for clues: changes in numbers, movements, health.

In fragmented urban landscapes, small mammals speak early, he said. They warn before silence arrives.

Their presence, he reminded participants, is not incidental. It is evidence of balance.

Narmadha on water testing pH level

Wings in the dark

As twilight thickened, Dr. Tharaka Kusuminda introduced mist netting — fine, almost invisible nets used in bat research.

He spoke firmly about ethics and care, reminding all present that knowledge must never come at the cost of harm.

Bats, he said, are guardians of the night: pollinators, seed dispersers, controllers of insects. Misunderstood, often feared, yet indispensable.

“Handle them wrongly,” he cautioned, “and we lose more than data. We lose trust — between science and life.”

The missing voice

One of the evening’s quiet revelations came from Sanoj Wijayasekara, who spoke not of what is known, but of what is absent.

In other parts of the region — in India and beyond — researchers have recorded female frogs calling during reproduction. In Sri Lanka, no such call has yet been documented.

The silence, he suggested, may not be biological. It may be human.

“Perhaps we have not listened long enough,” he reflected.

The wetland, suddenly, felt like an unfinished manuscript — its pages alive with sound, waiting for patience rather than haste.

The overlooked brilliance of moths

Night drew moths into the light, and with them, a lesson from Nuwan Chathuranga. Moths, he said, are underestimated archivists of environmental change. Their diversity reveals air quality, plant health, climate shifts.

As wings brushed the darkness, it became clear that beauty often arrives quietly, without invitation.

Sanoj on female frogs

Coexisting with the wild

Ashan Thudugala spoke of coexistence — a word often used, rarely practiced. Living alongside wildlife, he said, begins with understanding, not fear.

From there, Sethil Muhandiram widened the lens, speaking of Sri Lanka’s apex predator. Leopards, identified by their unique rosette patterns, are studied not to dominate, but to understand.

Science, he showed, is an act of respect.

Even in a wetland without leopards, the message held: knowledge is how coexistence survives.

When night takes over

Then came the walk: As the city dimmed, Beddagana brightened. Fireflies stitched light into darkness. Frogs called across water. Fish moved beneath reflections. Insects swarmed gently, insistently. Camera traps blinked. Acoustic monitors listened patiently.

Those walking felt it — the sense that the wetland was no longer being observed, but revealed.

For many, it was the first time nature did not feel distant.

Faunal diversity at the Beddagana Wetland Park

A global distinction, a local duty

Beddagana stands at the heart of a larger truth. Because of this wetland and the wider network around it, Colombo is the first capital city in the world recognised as a Ramsar Wetland City.

It is an honour that carries obligation. Urban wetlands are fragile. They disappear quietly. Their loss is often noticed only when floods arrive, water turns toxic, or silence settles where sound once lived.

Commitment in action

For Dilmah Conservation, this night was not symbolic.

Speaking on behalf of the organisation, Rishan Sampath said conservation must move beyond intention into experience.

“People protect what they understand,” he said. “And they understand what they experience.”

The Beddagana initiative, he noted, is part of a larger effort to place science, education and community at the centre of conservation.

Listening forward

As participants left — students from Colombo, Moratuwa and Sabaragamuwa universities, school environmental groups, citizens newly attentive — the wetland remained.

It filtered water. It cooled air. It held life.

World Wetlands Day passed quietly. But at Beddagana, something remained louder than celebration — a reminder that in the heart of the city, nature is still speaking.

The question is no longer whether wetlands matter.

It is whether we are finally listening.

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoHayleys Mobility ushering in a new era of premium sustainable mobility

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoSLIM-Kantar People’s Awards 2026 to recognise Sri Lanka’s most trusted brands and personalities

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoAdvice Lab unveils new 13,000+ sqft office, marking major expansion in financial services BPO to Australia

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoArpico NextGen Mattress gains recognition for innovation

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoAltair issues over 100+ title deeds post ownership change

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoGovt. provoking TUs

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoSri Lanka opens first country pavilion at London exhibition

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoAll set for Global Synergy Awards 2026 at Waters Edge