Features

School bags

(Excerpted from Life is a Frolic by Goolbai Gunasekara)

The lives of school going children these days is so far removed from mine that kids of today may almost be living on another planet. Customs and attitudes today are weird. I watched with open mouthed amazement as granddaughter KitKat got ready for school.

First, she put her swimsuit into her school bag. This was followed by a slightly damp towel plus an extra shirt. A board game and a cassette were flung in after all this.

“Haven’t you forgotten something?” I ask somewhat bewildered by the contents.

“Oh yes,” she added her Tuck Shop pocket money. “Nothing else?” I inquired silkily.

KitKat distrusts politeness from me. She is more comfortable with a yell.

“Er… like what?”

“A school text perhaps? An exercise book or two. You DO intend to do some writing in school don’t you?”

She looks affronted but repacks her bag.

Now let’s take my day at Bishop’s far removed from the present. One never forgets the routine and discipline of parents half a century ago as opposed to the apparent laxity of today.

We were woken at 5 a.m. Bags were packed the previous night with parents reminding us of the necessary chore every five minutes.

“Have you packed your school bag?”

The answer was always yes. We dared give no other. And what went into this school bag? Only school related stuff of course. Parents checked. The parental grapevine was abuzz with the latest news that Lady ChatterIay’s Lover had been found in a grade 11 school bag. It was rumoured that Sister Gabrielle, our tall and gracious Principal, had looked at the novel and had to be revived with smelling salts. Bishop’s was an Anglican school but a few Anglican nuns were always around to be shocked by modernity.

On the dot of 6.30 a.m. if Father was in Sri Lanka in between lecture tours, he personally saw me off on my bike, from the back verandah. Su, my younger sister, was perched atop our own rickshaw parked alongside the car in the garage. Between puller Murthy and Su, was a running battle. Father knew this.

“Now, not a WORD to Murthy except a polite one,” he would caution sternly. Su tossed her pretty head. She enjoyed the rickshaw ride with two or three boys cycling alongside making appreciative comments. Murthy did not approve of silly romance. He raced from Rosmead Place to St Bridget’s at a speed Roger Bannister might have envied. Su fumed. It was just up one road and down the other after all.

Parents did not have cars on the ready to drop us. Many of us cycled – especially those who lived within a hoo gana distance from the school.

“It’s raining mother. Can Weerasuriya drop me?”

My Father did not like the thought of the car getting wet and remaining wet the whole day. He had no problem with me getting wet so the answer was predictable.

” Wait till the rain ceases and make a dash for it.”

Traffic was at a minimum. ‘Making a dash’ for anything was extremely easy. Besides which, one could always make use of a slightly damp look.

“Miss I got wet coming to school,” we would tell our Form teachers. A realistic little cough further enforced the idea that we were sickening for colds.

“Run to the sick room right now dear,” said a concerned mistress. She didn’t want us breathing germs all over the class for the next few days. Properly executed that visit to the sickroom could be dragged out to cover two periods.

Then there was the ‘bag search’. Unless they were School Prefects, girls were not considered particularly trustworthy. What am I saying. They were considered totally untrustworthy by every member of the school staff. Ergo, bags were searched once a week for ‘undesirable fiction.’

Of course, we read undesirable fiction but we had the sense not to leave these exciting tomes lying round in our school bags. There were other things – too sacred to even mention, which we tucked into our bras and discussed with bated breath. These were romantic missives which class beauties like Chereen received regularly and were delivered by help karayas like myself with no boyfriend of my own.

Granddaughter KitKat views my school days with disbelief.

“How did you stand it Achchi? Nothing happened in your time.” Ah but that’s what she thinks. We certainly had our moments.

(Life is a Frolic is available at leading booksellers)

Features

Polio scourge: An addendum

By Dr B. J. C. Perera

By Dr B. J. C. Perera

MBBS(Cey), DCH(Cey), DCH(Eng), MD(Paed), MRCP(UK), FRCP(Edin), FRCP(Lond), FRCPCH(UK), FSLCPaed, FCCP, Hony. FRCPCH(UK), Hony. FCGP(SL)

Specialist Consultant Paediatrician and Senior Fellow, Postgraduate Institute of Medicine

This is a scientific supplement to the excellent article, titled “The saga of the control of the dreaded disease polio,” written by my friend, Dr Jude Jayamaha, Consultant Virologist, and published in The Island newspaper on 28 October 2024. He most eloquently described the initial development of the vaccine that helped in no small measure to control this disease in children, as well as in adults.

Polio, the shortened name for the much-feared illness known by the scientific name, Poliomyelitis, is a disease caused by a virus that specifically attacks the nerves of the human body. The virus enters the body through the gastrointestinal tract in contaminated food and water. Once it spreads widely in the body, the virus causes total disruption of the functioning of the nerves and leads to paralysis of the muscles supplied by the nerves. It has three strains, or types, and all of them cause destructive effects on the nerves.

There is no specific curative treatment, no antiviral medicines that are effective against the virus, and even in those who recover to some extent, there is permanent paralysis of the affected muscles. When the muscles that are involved in breathing are affected, there is a major disturbance in respiration, sometimes leading to complete respiratory paralysis.

The so-called Bulbar Poliomyelitis that affects the nerves that supply the muscles used in swallowing produces a marked problem with swallowing, even the normal secretions in the mouth and throat being affected. The accumulation of these secretions results in aspiration of the same secretions into the lungs with intense suffocation. In every sense of the description, the disease causes intense suffering, leads to a significant number of deaths, and leaves the rest of those affected, maimed for life.

I have seen very many cases of polio in children as a Medical Student, an Intern Medical Officer, a Medical Officer in the Out Patients Department (OPD) of the Lady Ridgeway Hospital (LRH) and then as a Specialist Paediatric Registrar at LRH, over the period from the late 1960s to the mid-1970s. Many affected children died and those who managed to survive were left with terrible and permanent loss of power in some muscles and grotesque deformities. This latter lot was mutilated forever with no long-term recovery.

I have had to put babies into the so-called “Iron Lung” or negative pressure cuirass respirators with my own hands, because their respiratory muscles were paralysed, knowing very well that none of them were going to come out alive. The degree of human suffering inflicted by this little polio virus was totally unbelievable.

The original Salk vaccine, which Dr Jude Jayamaha described in detail, had to be given by injection. It was quite effective and very definitely caused waves in the affluent countries of the Western hemisphere. However, most unfortunately, it was not made available to many of the poorer countries, probably due to constraints imposed by inadequate production.

In a twist to the tale of polio, a young man of 15 years by the name of Abram Saperstejn, born to Polish-Jewish parents in the Russian Empire, emigrated on the ship SS Lapland to the United States of America (USA), and changed his name to Albert Bruce Sabin. This bright young man trained in medicine and then conducted research in the Lister Institute for Preventive Medicine in England. Much later he came back to the USA and developed an oral inactivated or attenuated vaccine using mutant strains of the polio virus, the vaccine being known as ‘polio drops’.

This oral vaccine that covered all three strains of the polio virus was licensed in the USA in 1962. It really worked like a charm but needed a very high coverage in children to provide maximum benefit with a large population that had what we call ‘herd immunity’. Following in the footsteps of Jonas Edward Salk who discovered and propagated the very first injected Salk vaccine, Alfred Bruce Sabin, too, refused to get a patent for his oral vaccine. As a result, the vaccine could be freely marketed at a relatively low price.

The Sabin trivalent oral polio vaccine (tOPV) was introduced to Sri Lanka in 1962 as part of the country’s Expanded Programme of Immunization (EPI). However, quite sadly, it took Sri Lanka approximately two decades to achieve over 90% coverage of children for polio immunization, which occurred only by the early 1980s. That is why we were still seeing cases of polio in the late 1960s and mid-1970s.

From the time I became a Consultant Paediatrician in 1978, up to the present, I HAVE NOT SEEN A SINGLE CASE OF POLIO. The success of the immunization programme in Sri Lanka, combined with other public health measures, eventually led to the elimination of polio in the country, with the last indigenous proven polio case being reported in 1993. Sri Lanka was officially certified as polio-free by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2014.

Need we say more? The earlier article by Dr Jayamaha and this documentation are excellent examples of the wonderful achievements of modern medicine. In effect, they are also accolades of the highest level to all those lovely people, from Dr Jonas Edward Salk and Dr Alfred Bruce Sabin, to all those who have been in, and continue to be involved in, the Immunisation Programmes worldwide. Among many other things, the selfless dedication of all of them has been instrumental in protecting our people from a brutal and untreatable disease such as Poliomyelitis.

Features

187th Anniversary Kandy Friend-In-Need Society

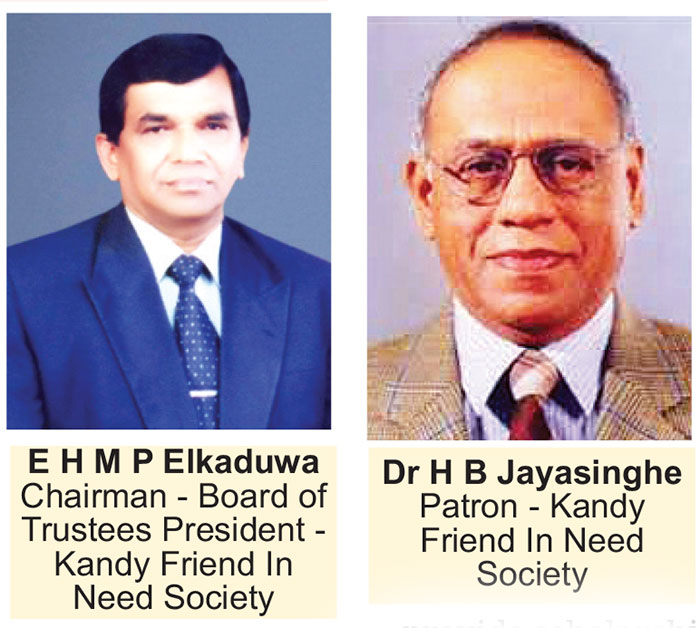

by E H M P Elkaduwa

Chairman – Board of Trustees

President – Kandy Friend In Need Society

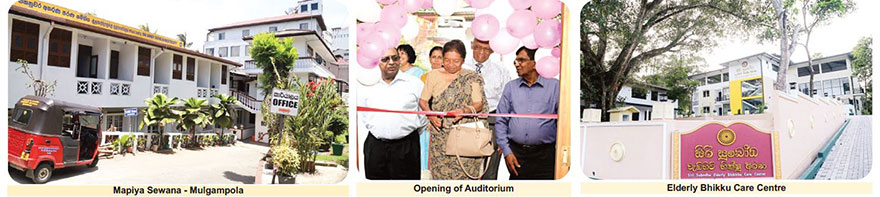

The Kandy Friend-In-Need Society (KFINS), established in 1837, is one of the oldest social service organisations operational in Sri Lanka. It has been providing social welfare services over a period of almost two centuries. Due to the dedication, sacrifice and financial discipline of the members who have held responsible positions in the Society over this period, we now have fixed assets worth Rs. 1,000 million and financial assets worth about Rs. 60 million.

However, a matter of concern to the Board of Trustees at this juncture is how to ensure the sustainability and continuing of this organisation as well as its social welfare services ensuring credibility, safety and security. In this connection it would be pertinent to identify the important factors that have contributed to KFINS’s success over such a long period of time as a model social welfare service provider, winning the goodwill and confidence of the general public, who continuously offer Daana to the elders.

Relentless efforts of the membership, members of the Board of Trustees, members of the management council, excellent services rendered by the staff members are our strengths. Non consideration of ethno-religious differences and ensuring utmost transparent in financial assets management are other factors to our success. At present we are offering residential accommodation to 100 elders at Mulgampola Mapiya Sevana and 50 at Ampitiya.

To meet the demand of the middle income elders owing to the migration of their children, we have 30 rooms at Mulgampola and six cottages at Ampitiya. One of our outdoor activities is to look after elders in remote areas under ‘Adopt an Elder program’, our Foster Children’s Education, scholarship programme is providing 100 scholarships for rural area children, 100 students of plantation school children are provided with books and educational instruments and under the Prem Weerakoon scholarship scheme we provide scholarships to university students.

Our Society was founded in 1837 by the then British Governor of Ceylon, Sir James Alexander Mackenzie. A block of land at Mulgampola with an old factory building was donated to it by the British Planter, W H Pate. The Elders’ Home was officially inaugurated later by the British Governor at the time, Sir Andrew Caldecott.

The elders who are with us are mostly those neglected by their own families and others. We look after them as our own parents.

Features

Waiting for a Democratic Opposition

by Tisaranee Gunasekara

“The future is cloth waiting to be cut.”

Seamus Heaney (The Burial at Thebes)

The point had been made often enough. Without a Gotabaya Rajapaksa presidency, there wouldn’t have been an Anura Kumara Dissanayake presidency. For the NPP/JVP to go from three percent to 42 percent in four plus years, the system had to be broken from within by the very leaders entrusted with its care by a majority of voters. Gotabaya Rajapaksa achieved that feat in ways inconceivable even by his most stringent critics (who in their sane minds could have imagined the fertilizer fiasco?).

But President Dissanayake’s victory has two other fathers: Ranil Wickremesinghe and Sajith Premadasa. President Dissanayake won because the competition was so uninspiring. It was more a case of Sajith Premadasa and Ranil Wickremesinghe losing rather than President Dissanayake winning. While the NPP’s rise was meteoric, President Dissanayake failed to gain 50 percent mark of the vote. He is Sri Lanka’s first minority president.

As the IHP polling revealed continuously, all major presidential candidates had negative net favourability ratings; they were more unpopular than popular. The election was a contest to pick the least unpopular leader. Thus the winner’s inability to clear the 50 percent line.

This situation hasn’t changed qualitatively in the run up to parliamentary election. According to the latest IHP poll, President Dissanayake’s net favourability rating is still negative, which means more people regard him unfavourably than favourably. He and Harini Amarasuriya are at minus 10, the least unpopular of leaders. Sajith Premadasa at minus 31, Ranil Wickremesinghe even lower, lag behind not just President Dissanayake and Ms. Amarasuriya, but also the now retired Ali Sabry.

The NPP/JVP is likely to clock a bigger win at the parliamentary election even so, because the oppositional space is clogged by Mr. Wickremesinghe and Mr. Premadasa, with the Rajapaksas hanging on to the seams. The same actors representing the same unattractive futures. Compared to these prospects, a Harini Amarasuriya premiership would seem alluring to most Sri Lankans (she is an excellent choice, in any case, for the job).

President Dissanayake has avoided any obvious missteps in his first month. He is treading cautiously, especially in the economic arena, opting not even to tweak Ranil Wickremesinghe’s deal with a group of ISB holders, despite some unfavourable – and precedent-making – clauses such as giving bondholders the option of changing the law underpinning them from New York to England or Delaware; New York is about to pass a bill giving debtor nations greater bargaining power. He is no Gotabaya, at least economics.

In Sri Lanka, it is normal for the party that wins the presidency to win the parliament as well. In 2010, after Mahinda Rajapaksa won the presidential election, the opposition unity fractured. The UNP contested on its own and the JVP contested in an alliance with the defeated presidential candidate, Sarath Fonseka. In the presidential election, Mr. Fonseka had polled 4.2 million. At the parliamentary election, the main oppositional party, the UNP, polled only 2.4 million. Even after the votes for the Tamil and Muslim parties and the JVP/Fonseka headed DNA were factored in, this amounted to an erosion on a massive scale – 1.2 million votes.

In 2019, Sajith Premadasa polled 5.6 million votes. Yet his newly formed SJB polled a mere 2.8 million at the 2020 parliamentary election. Once the votes given to Tamil and Muslim parties and the UNP were factored in, this amounted to a bigger erosion, over 2 million votes.

Even the Rajapaksas could not buck this general trend in 2015. The UNP won the general election despite the much vaunted Mahinda Sulanga.

So the NPP/JVP winning on November 14 would be the norm. The only question is about the extent of that victory: would it be limited to a simple majority or something bigger, close to a two thirds?

A simple majority would be necessary to run an effective government. But a near two thirds victory would be a tragedy. Every time a Sri Lankan party won so big, disaster ensued in 1956, 1970, 1977, 2010 and 2020. Too much power not just corrupts but also stupefies. A future NPP/JVP government might be able to avoid the (financial) corruption trap. But if burdened with a huge majority the government will not be able to evade a blunting of senses, of growing blindness and deafness to public distress, of an addling of wits. Already, future ministers are shrugging off price hikes in such staples as rice, calling them normal. They might be but the dismissive attitude hints that the rot of indifference to public pain might have begun to set in already. In the absence of a strong, principled, and effective opposition, the rot will grow faster, to the detriment of all Sri Lankans, including compass enthusiasts.

Feudal ethos and tyrannical practice

To be fully functional, a bourgeois democratic system needs bourgeois democratic parties. Unfortunately, most Sri Lankan parties are feudalist in ethos and tyrannical in practice. We have a history of leaders treating their parties as private or familial property. The Rajapaksas are the most egregious example but they didn’t start the habit, merely took it to a new low. Senanayakes and Bandaranaikes preceded the Rajapaksas, both families treating dynastic succession as the norm.

When he became the leader of the UNP, J.R. Jayewardene made a clean break with that feudalist ethos. He delinked the UNP from familial politics and opened it to new blood, providing the space for the creation of a line of brilliant second level leaders. In 1977, he allowed the candidates for the upcoming parliamentary election to choose a steering committee to manage the campaign (in a secret vote). The man who topped that internal poll was made the deputy leader, Ranasinghe Premadasa.

Had Mr. Jayewardene won a simple majority in 1977, history might have turned out differently and better. But he won a five sixth majority. It didn’t take long for hubris to set in, making a man of undeniable intellect commit a bunch of avoidable mistakes and unnecessary crimes. And having obtained undated letters of resignation from all parliamentarians, Mr. Jayewardene ran the party like a dictator. Unlike the Bandaranaikes and Senanayakes, he didn’t crown his offspring. Instead, he turned himself into an uncrowned king.

Ranil Wickremesinghe opted for a dictatorial leadership style from day one. He gave himself the title The Leader, changed the party constitution to make it literally impossible to effect leadership changes, marginalised potential challengers and promoted untalented loyalists. He slowly abandoned the J.R./Premadasa UNP’s anti-feudal ethos, turning the UNP into a party where preferment was given to spouses, siblings and offspring of politicians.

As president, Mr. Wickremesinghe prevented the economy’s freefall and achieved a turn around. The NPP government’s decision to go the same route, at least for now, is a tacit admission of the success President Wickremesinghe achieved under extremely difficult circumstances. Yet, his me-or-deluge attitude to the UNP continued and continues. As president, instead of allowing a new young leadership to rebuild the party, he kept control of the UNP via discredited and deeply unpopular yes men. After his humiliating defeat, he clings to the party leadership.

Sajith Premadasa in this department is a veritable Wickremesinghe clone. He has suffered three national defeats, losing the presidency twice and the parliament once. Yet, like Mr. Wickremesinghe, he seems determined to cling to the SJB leadership even at the cost of running the party to the ground. He is also allowing his family into politics. Consequently, the SJB too has become a party unsuited to a bourgeois democratic system, feudal in ethos, dictatorial in style.

Anura Kumara Dissanayake won the presidency because the JVP understood its own un-electability and created a more electable cocoon as cover, the NPP. Sajith Premadasa and Ranil Wickremesinghe are incapable of even such minimal evolution. Like the woolly mammoths who couldn’t adapt to climate changes and were hunted extensively, their inability to adapt to the new political climate created by the NPP/JVP victory would drive their own parties to extinction. With no opposition to keep it on its toes, the government would succumb to hubris sooner rather than later.

The rest would be history. All too familiar history.

Somethings new, one thing old

What if J.R. Jayewardene did not commit the deadly mistake of banning the JVP on totally fabricated charges?

The JVP entered the democratic mainstream in 1977. From then till about 1983, the JVP was non-racist, trying to reach out to Tamils along the lines of class solidarity. It also treated the SLFP as its main enemy, and dreamted of becoming the main opposition (thus the famous lecture series: The Journey’s end for the SLFP). The JVP leadership maintained contact with some government leaders (especially Prime Minister Premadasa). When the opposition launched the general strike of July 1980, the JVP criticised the move and stayed out of it (the strike failed and the government sacked 60,000 striking workers). At a personal level, Mr. Wijeweera got married and started raising a family. These were hardly the actions of a party or a leader harbouring insurgent intentions.

Mr. Wijeweera’s abysmal performance in the 1982 election created a crisis in the JVP. The party’s reversion to a more Sinhala-oriented line was arguably a reaction to the shock of defeat. Yet going the armed revolution path was never on the JVP’s agenda even then. Had President Jayewardene not extended the life of the existing parliament (in which his UNP had a five sixth majority), the JVP would have contested the next general election (scheduled for 1983), won a few seats and settled down into standard parliamentary existence of reform and compromise.

Not only did President Jayewardene postpone parliamentary polls. He also banned the JVP. It was that criminal error which led to the second JVP insurgency (the insurgency’s racist, brutally intolerant nature was the JVP’s choice alone).

Perhaps President Dissanayake is where Mr. Wijeweera would have been had parliamentary election not been postponed and the JVP not been banned. Unfortunately, the JVP’s commendable evolution on matters economic has not been paralleled in the ethnic problem arena. The NPP was remarkably reticent on the subject in its tome-like presidential manifesto. Listening to the JVP general secretary Tilvin Silva indicates the reason. Behind a non-racist façade, the JVP is as regressive about the Tamil question today, as it was in the past.

“After 1970, our major political parties became provincialized gradually,” Mr. Silva said in a recent TV interview when asked about the NPP’s unimpressive electoral performance in the North and the East. “This allowed new forces to come into being in the North, the East, and the plantations… Tamil parties in the North, Muslim parties in the East, plantation parties in the plantations… So these parties decided on how to vote. For example, the people of the North did not vote freely. They voted according to what the TNA decided.”

Not a word about how the supposedly national parties alienated Tamils via discriminatory policies and violence actions, nothing about the disenfranchisement of Upcountry Tamils, Sinhala Only, the race riot of 1958, the standardization of university admissions in 1971 or the brutal attack on the Tamil Language Conference in Jaffna in 1974. Nothing of that history exists in the JVP’s universe, according to Mr. Silva. He admits to the existence of a language problem. The rest is reduced to water, markets, schools and education.

Perhaps the most telling is how he explains the land issue. “During the war some left their lands. Then they couldn’t return. Those who stayed back grabbed the land. Now when the owner goes back someone else is in occupation. So there’s a fight. So the government must intervene, set up land kachcheris and solve the problem.” Not a word about the continued military occupation 15 years after the war ended, the military’s ongoing attempts to grab more land or the road closures which hamper ordinary life. So like the Rajapaksas.

Mr. Silva accuses the Tamil leaders of talking about the 13th Amendment and devolution to protect their own interests. “But people on the ground don’t want 13; they don’t want devolution of power…” Even if that argument is granted, what about the thousands of acres occupied by the military? According to the JVP’s reading, do the Tamil people want their land back from the military, or not? Do they want their roads opened or not? Do they want justice for their dead or not? If the JVP cannot understand those basic demands and yearnings, if the best solution it can offer is administrative decentralisation (under a de facto military occupation), the NPP won’t make much headway in creating a Sri Lankan nation. If Sri Lanka’s road ahead lies between a Sinhala government and a feudalist autocratic (and ineffective opposition), the next five years are unlikely to be all that different from the last 76.

(First published in Groundviews)

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoStandard Chartered appoints Harini Jayaweera as Chief Compliance Officer

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoWickremesinghe defends former presidents’ privileges

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoRestructuring education to align with global demands

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoFive-star hotels stop serving pork products

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoDevolution and Comrade Anura

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoChamika, Anuka shine as Mahanama beat Nalanda

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoFifteen heads of Sri Lanka missions overseas urgently recalled

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoMilo powered Schools Netball finals from November 4